28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

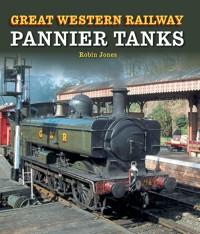

The name 'Great Western Railway' immediately conjures up images of Stars, Castles and Kings, the legendary express passenger locomotives that were the envy of the world in their day. However, the Swindon empire also produced extensive fleets of all-purpose tank engines - everyday reliable workhorses and unsung heroes - which were standout classics in their own right. The most distinctive and immediately recognizable type in terms of shape, all but unique to the GWR, was the six-coupled pannier tank. With hundreds of photographs throughout, Great Western Railway Pannier Tanks covers the supremely innovative pannier tank designs of GWR chief mechanical engineer Charles Benjamin Collett, the appearance of the 5700 class in 1929, and the 5400, 6400, 7400 and 9400 classes. Also, the demise of the panniers in British Railways service and the 5700s that marked the end of Western Region steam, followed by a second life beneath the streets - 5700 class panniers on London Underground. Also covers Panniers in preservation, plus cinema and TV roles and even a Royal Train duty. Superbly illustrated with 260 colour and black & white photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 256

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY

PANNIER TANKS

Robin Jones

First published in 2014 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Robin Jones 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may bereproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording,or any information storage and retrieval system, withoutpermission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the BritishLibrary.

ISBN 978 1 84797 654 3

DedicationTo Jenny, Vicky and Ross

Photographic AcknowledgementsThose who provided pictures for this book are credited withthe captions; pictures by Ben Brooksbank, Hugh Llewellyn,Ben Salter, 8474Tim, Chris Howells, Tony Hisgett and PeterBroster are published under a Creative Commons licence.Full details may be obtained at:http://creativecommons.org/licences.

Frontispiece: GWR 57XX No. 9600 takes pride of placeon the turntable during an open day at Tyseley LocomotiveWorks, with fellow Collett-designed 4-6-0s No. 4936 KinletHall and Castle No. 7029 Clun Castle in the background.ROBIN JONES

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 Britain’s Biggest Class of Tank Engines

2 The Inventor and the Innovator

3 The Ancestry of the 5700 Class

4 The 57XX Blueprint Takes Shape

5 The 5700s and their Variants

6 The Demise of the 57XXs

7 A Second Life Beneath the Streets

8 Sisters and Successors: Panniers and Auto-Trains

9 More Panniers Big and Small

10 Panniers in Preservation

Index

INTRODUCTION

From the outset, the Great Western Railway set out not only to be better than the rest, but very different, too. Its unique independence-with-attitude approach all began when its first engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, ripped up the rule book, started all over again with a very wide blank sheet of paper, and insisted that the railway was built to his unique broad gauge, with the rails 7ft 0¼in (2.14m) apart.

When asked to design the railway that would connect London to Bristol, condensing a journey that took several days by stagecoach into one of a few hours, Brunel aimed to do much more. Brunel, appointed by the GWR when he was just twenty-seven years old, demanded the right to build a luxury people carrier, one which would be the pride of all Britain, and a marked improvement on the country’s early passenger-carrying railways. He had seen for himself the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, the world’s first inter-city line, which became an overnight sensation when it opened on 15 September 1830, but had been less than impressed.

That railway had been built to engineer George Stephenson’s track gauge of 4ft 8½in (1.44m), which had been based on measurements of the axles of coal carts in north-east England. However, the critical Brunel found that the line’s four-wheel coaches gave an uncomfortable ride, and aware that GWR passengers would include the well-to-do travelling to the Regency spa resort of Bath, never mind those who journeyed on across the Atlantic to New York by means of his globe-shrinking steamships from Bristol, would demand something more luxurious.

He responded to the challenge by designing his own gauge for the GWR, one that would see bigger locomotives with wheels placed outside their frames, permitting much larger boilers to be used and thereby creating a greater capacity for speed. The wider gauge would allow larger wheel diameters, lessening the effect of friction while facilitating the ability to build wide carriages with bodies mounted as low as possible, minimizing air resistance – never mind the fact that most of the rest of Britain and then the world was building to Stephenson’s gauge, which eventually became known as ‘standard’ gauge, and the fact that trains on one system could not physically run on to another. Brunel asked Lord Shaftesbury, who drafted the successful Great Western Railway Bill of 1835, to omit any clause stipulating what gauge could be used, so he could be given a free hand.

So where did Brunel get his 7ft 0¼in (2.14m) gauge from? The measurement just so happened to be identical to that used on a short rope-worked railway at Chatham Docks that his father Marc had laid several years before.

As Britain’s railway network grew in the decades that followed, so did the controversy over its gauge. The GWR repeatedly showed that broad gauge was faster and carried bigger payloads, but could not avoid the fact that it was left as a minor player in a country seeking a one-size-fits-all national network. Broad gauge finally died over the weekend of 21–23 May 1892, when an army of more than 4,200 platelayers and gangers converted all 177 miles (285km) of the main line between Paddington and Penzance from broad to standard gauge.

Despite the slow and protracted demise of the still arguably superior broad gauge, the GWR continued steadfastly to do its own thing when it felt it knew better than others. Although it did not invent the steam railmotor concept, in which a locomotive and carriage are built as a single self-contained unit, in Edwardian times the GWR became the first to build a fleet of them, having a total of ninety-nine in service by 1908.

GWR 57XX No. 5764 picks up speed at Eardington on the Severn Valley Railway on 25 September 2009. RAY O’HARA

Similarly, in 1933 the GWR introduced the first of what was to become a very successful series of diesel railcars, building up a fleet of thirty-eight between then and 1942, at a time when other British railways had been dithering over whether to introduce the concept into a world in which steam still reigned supreme despite other options becoming available. In this the GWR was certainly proved right.

The Paddington-Swindon empire was renowned for its fierce spirit of independence, which was by no means quashed when Britain’s railways were nationalized on 1 January 1948. The GWR became the Western Region, but in many ways continued in its own individual direction, as if nationalization were little more than a name change.

After the years of wartime austerity diminished and money became available to modernize the country’s network, diesel and electric traction were seen as the future – indeed, Britain was lagging behind many other Western countries in this respect. British Railways’ 1955 ‘Modernization Plan’ finally called for the rapid eradication of steam, which up until then had been the preferred choice: at that time, only five diesel locomotives were running on the British main line, all of them diesel-electric types. But after the Modernization Plan was published, several locomotive manufacturers were encouraged to build diesels, and most of the types that were eventually adopted for mass production were diesel electrics.

But the Western Region yet again insisted on being different and chose diesel-hydraulic types, based on the introduction of V200 locomotives by the German Federal Railways in 1953. Diesel-hydraulic locomotives were lighter than diesel-electric equivalents, and had a better power/weight ratio, leading to decreased track wear. Yet even the best hydraulic transmissions were capable of handling engines with a power output only of around 1500hp, and more powerful locomotives would need a pair of engines and transmissions.

Replica GWR broad-gauge 2-2-2 Fire Fly on the broad-gauge demonstration line at Didcot Railway Centre. Brunel’s broad gauge is the most famous example of the GWR ploughing its own furrow rather than following the rest, and its widespread and trademark adoption of the pannier tank design may be viewed as another. FRANK DUMBLETON

Dropping the fire from 57XX No. 3738 after an evening photoshoot at Didcot Railway Centre on 9 February 2008. FRANK DUMBLETON

The Western Region carried on with the GWR ‘go it alone’ tradition dating from the days of Brunel. While all other regions of the nationalized railway network opted to modernize with diesel-electric traction, the still independent-minded WR opted for diesel-hydraulic locomotives. Similarly, and all but uniquely amongst British railway companies, its predecessor the GWR produced huge fleets of pannier tanks. Pictured is preserved Severn Valley Railway-based Class 52 D1062 Western Courier on the turntable at Minehead during a visit to the West Somerset Railway in 2009. ROBIN JONES

Diesel hydraulics versus diesel electrics turned out to be the broad- versus standard-gauge debate again by the back door. While several of the Western Region diesel-hydraulic classes were indeed successful, they did not fit into British Railways’ ‘one size fits all’ overall scheme of things. Western Region diesel hydraulics may be fine between Paddington and Penzance, but if they ran to other parts of the national network, there were problems of depots being unfamiliar with their maintenance. From the late sixties onwards, the diesel hydraulics were phased out as part of standardization policies, many having lasted only a fraction of the time in service of the steam locomotives they had replaced. The final Western Region diesel hydraulics, the last of the superb Class 52 Western Co-Cos, were withdrawn in 1977.

Its historic go-it-alone approach to railway evolution left the GWR and its successor the Western Region with distinctive locomotive and rolling stock types, ones that are immediately and unquestionably recognized as products of the Swindon design teams. In this respect, the best known example must surely be one of the most successful European steam locomotive designs of all time: the GWR 0-6-0 pannier tank.

CHAPTER ONE

BRITAIN’S BIGGEST CLASS OF TANK ENGINES

There are several types and variations of GWR pannier tank: the description is taken from the baggage carried on either side of a donkey or pack mule, and is applied to steam locomotives by virtue of the oblong water tanks on either side of the boiler.

As we shall see, there were many different types of pannier tank on the GWR, the earliest examples being converted Victorian saddle-tank classes. However, by far the biggest class, and the one that formed a benchmark in railway history, was the 5700 or 57XX class. A total of 863 examples were built between 1929 and 1950, making it the second biggest steam locomotive class in British railway history. That in itself is surely testament to their usefulness and versatility, being equally at home on passenger, freight or shunting duties.

They were found right across the GWR system, hauling empty coaching stock in and out of Paddington, heading rural branch line services and marshalling coal trains in the South Wales coalfield. After nationalization, several found their way to other regions of British Railways, giving sterling service until the inevitable happened and they were ousted by diesels. Several were sold off privately into industry, and thirteen were eagerly bought by London Transport to haul engineering trains on London Underground. The relationship between the Underground and the GWR had therefore turned full circle, because in 1863, when the first section of the Metropolitan Railway, the world’s first underground line, opened, the GWR supplied broad-gauge engines to run services.

Carrying the maroon London Transport livery, these panniers outlived steam on British Rail by several years, the last Underground pannier coming out of service on 6 June 1971, while some 57XXs lasted in National Coal Board ownership for several years. After their final fires in steam-era revenue-earning service were thrown out, several GWR panniers were given a new lease of life in Britain’s growing portfolio of preserved railways, where they remain a familiar and popular sight to this day.

Only the London & North Western Railway DX Goods 0-6-0 tender locomotives formed a larger class than the 57XXs, with a total of 943 built at Crewe between 1858 and 1872. Withdrawals began in 1902 and ended in 1930, and not one example survived. However, if you take into account the sister and derivative classes of the 57XX that came into existence after it proved its great worth within a short space of time, in particular the 210 members of the 94XX class – the 57XX’s taper-boilered successors built between 1947 and 1956 – the number of post-1929 GWR pannier tanks is far higher.

Glasgow-born engineer John Haswell, who was born on 9 June 1812, built what is viewed by some as a forerunner to the Belpaire firebox (see box [above]), when he was employed by the Vienna Glognitzer Railway. He died in Vienna on 8 June 1897.

It was William Thorneley, however, who was credited with introducing the Belpaire firebox to Britain. Thorneley was headhunted by Thomas Parker, the locomotive, carriage and wagon superintendent of the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway, and moved from Beyer Peacock Ltd to the line’s Gorton Works in Manchester. Thorneley, who had also previously worked for Sharp Stewart and the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway, retired through ill health in 1906.

Belpaire fireboxes became a standard feature on most GWR locomotives, and also on many of the types designed and built by the London, Midland & Scottish Railway, whose chief mechanical engineer, Sir William Stanier, had been recruited from Swindon Works. Other British locomotive designers and railway companies also adopted the Belpaire firebox, but to nowhere near the extent of the LMS and GWR, which first began installing them at the end of the nineteenth century.

This is not the Bluebell Railway in Sussex, but the Bodmin & Wenford Railway in Cornwall, and neither is the 57XX No. 4666 as it seems, but home-based No. 4612 in disguise. It has temporarily adopted the identity of No. 4666, which once worked on the line from Bodmin Road (now Bodmin Parkway) to Bodmin General, Wadebridge and Padstow. RAY O’HARA

The Belpaire Firebox

The distinctive shape of the GWR pannier tanks is due to the use of the Belpaire firebox as the core design feature. Alfred Jules Belpaire was born in Ostend on 25 September 1820, and after attending the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in Paris, became an engineer. In 1860, he invented the square-topped firebox named after him.

His type of firebox has a greater surface area at the top, improving the transfer of heat and steam production. Its distinctive oblong shape makes attaching it to a boiler more difficult, but it has the advantage of simpler interior bracing. Belgium began using pannier tanks in 1866.

The fourth most prolific builder of locomotives in the USA, the Pennyslvania Railroad designed many of its engines with Belpaire fireboxes, and their square-shouldered shape became their trademark feature. The Pennsylvania Railroad and the Great Northern Railroad were unique in America in their endorsement of Belpaire fireboxes.

Belpaire died in Schaarbeek at the age of seventy-two.

Tyseley’s main line-registered 57XXs L94 (GWR 7752) and No. 9600 head the Vintage Trains ‘Cross City Rambler’ from Tyseley, through freight-only routes in the West Midlands such as the Sutton Park line to Walsall, and then on to Coalville and Nuneaton and back. IAN BARNEY

The distinctive feature: the pannier tanks from 57XX No. 4612 await fitting at the Flour Mill workshop at Bream in the Forest of Dean as it was rebuilt from a kit of parts. ROBIN JONES

Pannier tanks appeared on the continent, especially in Belgium, in the late nineteenth century, but in Britain they were mostly a GWR phenomenon. French-built Corpet 2ft gauge 0-6-0 No. 439 of 1884 Minas de Aller No. 2 was one of six that worked at a coal mine in Spain. Its restoration at the private Statfold Barn Railway near Tamworth, the home of the modern-day Hunslet Engine Company, has included the replacement of the rear section of the locomotive’s frames and the remanufacturing of almost all key components. ROBIN JONES

Right on time, WR 0-6-0PT No. 9466 brings the first train of the day, from Wembley Park via Harrow-on-the-Hill, into Amersham at 10.59 on Sunday 8 September. ROBIN JONES

CHAPTER TWO

THE INVENTOR AND THE INNOVATOR

The first few decades of the Great Western Railway largely belonged to the epoch of locomotives with massive single driving wheels, gleaming oversize steam domes, stovepipe chimney, and cabs without roofs to protect crews from the elements. The ‘modern’ era of twentieth-century GWR steam is regarded by many as having begun with the appointment of George Jackson Churchward as locomotive, carriage and works superintendent, a title changed in 1916 to the more familiar chief mechanical engineer.

George Jackson Churchward, who many argue was the greatest steam locomotive engineer of the twentieth century.

Having served an apprenticeship in the Newton Abbot works of the South Devon Railway near his birthplace of Stoke Gabriel near Torquay, and under Joseph Armstrong in Swindon Works, Churchward quickly rose through the GWR ranks during the period of the great transition from the broad- and mixed-gauge era to the standard-gauge epoch. Starting at Swindon as a draughtsman, he became carriage works manager, then works manager, and in 1897 was appointed chief assistant to locomotive superintendent William Dean.

Five years later he was promoted to the top job, and left a legacy that extended long beyond the boundaries of the Swindon-Paddington empire. In very broad terms, he was to the GWR in the twentieth century what Brunel and his locomotive engineer Daniel Gooch had been in the nineteenth: indeed, some consider him to be the greatest British steam engineer of all.

His first big success was the ten-strong City class of 4-4-0s, created by adding a new GWR standard No. 4 boiler with a sloping Belpaire firebox to an existing Atbara-class chassis. One of them, No. 3440 City of Truro, was unofficially recorded as reaching 102.3mph (164.6km/h) while descending Wellington Bank in Somerset with the ‘Ocean Mails’ special on 9 May 1904. It went down in legend as the first steam locomotive to break the 100mph (160km/h) barrier. For the GWR, Churchward came up with designs for 2- and 4-cylinder 4-6-0s that were substantially superior to any locomotive built by rival British railway companies.

Churchward brought to Britain many refinements from American and French steam locomotive practice in his drive to produce faster and more efficient machines. He took on board the Belpaire firebox and adapted it, rounding its corners, tapering its sides and sloping its top from front to rear: by doing so, he not only strengthened it, but provided greater circulation and heating potential next to the boiler. His seventy-three-strong 2900 or Saint class, his first 4-6-0s introduced in 1906, were the finest express locomotives in the country for many years. Their design, which began with the building of three prototype 2-cylinder 4-6-0 locomotives in 1902 and 1903, paved the way for the much later LMS ‘Black Five’ 4-6-0s and British Railways Standard 5s.

He devised the 2800 class of heavy freight engines, which were not bettered for many decades – and then he went one better than the Saints with the 4000 or Star class. He designed an experimental locomotive, No. 40 North Star, built as a 4-4-2 for comparative trials with 4-cylinder De Glehn compound locomotives that the GWR had bought from France. The trials reinforced Churchward’s faith in the balanced 4-cylinder layout, but he decided that he would produce the subsequent class with simple steam expansion, and with the 4-6-0 arrangement of the Saints. It is an understatement that the seventy-six Stars bettered even the Saints, and in their day were well ahead of the pack in terms of performance.

His choice of outside cylinders for express locomotives was not standard in the Britain of his day. The lines of the Stars, Saints and other Churchward classes are immediately recognizable as twentieth century, as opposed to the ‘antiques’ that preceded them. During his time in office, Swindon Works doubled in size.

The keynote Churchward policy was the standardization of locomotive parts, in particular boilers. It allowed components made for one type of locomotive to be fitted to several others, thereby increasing efficiency both in manufacture and maintenance and cost effectiveness. Churchward also introduced the first Pacific, or 4-6-2 locomotive to Britain, in the form of No. 111 The Great Bear, in effect a large Star, which appeared in 1912 on the Paddington to Bristol route.

What has all this to do with the origin of the 57XXs, you might ask. The answer lies in Churchward’s successor, Charles Benjamin Collett, who took over when he retired in January 1922.

Charles Collett

The son of a journalist, Collett was born on 10 September 1871 near Paddington station. He was educated at the Merchant Taylors School in London, and then attended London University. Afterwards he worked for marine engine builders Maudslay, Sons & Field of Lambeth.

In May 1893, Collett became a junior draughtsman in the Swindon drawing office. Four years later he was placed in charge of the section responsible for buildings, and in 1898 he became assistant to the chief draughtsman. Promoted to technical inspector at Swindon Works in June 1900, a few months later he became its assistant manager. However, he had to wait twelve years before he was elevated to the post of manager. There, he watched Churchward’s developments at first hand, and implemented them. He also developed a thorough understanding of works production, and saw where improvements could be made. He received the OBE for his efforts of producing munitions during World War I. Then in May 1919, he became deputy chief mechanical engineer.

Charles Benjamin Collett, the chief mechanical engineer who, in honing decades-old designs to new levels of perfection, produced some of the GWR’s best locomotives of all time.

Didcot-based 57XX No. 3650 catches the rays of the setting sun as it crosses Freshfield Bank on the Bluebell Railway on 18 November 2012. TOM HAWLEY/3650 GROUP

GWR 4-6-0 No. 6000 King George V on display at the Steam Museum in Swindon. Collett’s Kings were the most powerful of all GWR locomotive types and the class became the flagship of the company, yet they were in effect an enlargement of his Castle class, which in turn was an innovative development or enhancement of Churchward’s Star, rather than an altogether new design. Collett took the same approach when he designed new pannier tanks. ROBIN JONES

Churchward’s great success had been in dragging the GWR out of the post-broad-gauge era into the twentieth century, and he came up with designs that some considered were years ahead of their time. When he retired, at a time when revenue was falling and costs rising, the GWR was not seeking another great locomotive designer to fulfil the company’s immediate needs. What was required, however, was a man who would consolidate Churchward’s achievements while also modernizing production. At the time, these characteristics were seen as crucial.

Herein lies a real railway enigma. Under Collett, the finest GWR locomotives of all were produced, the Castle 4-6-0s and the ‘super Castles’ or Kings. Yet both were hardly original in concept, as the Stars and Saints had been. Collett inherited Churchward’s standard designs and took them to the next stage of evolution… but without coming up with radical new ones of his own. In doing so, he was a great innovator rather than an inventor in the mould of his illustrious predecessor. Herein lies the hallmark of Collett, who oversaw the zenith of GWR locomotive design and building.

By the 1920s, a requirement for a more powerful engine than the Stars arose, and Collett responded by enlarging the Star boiler to give a greater evaporative rate. The Star cylinders were increased in diameter, and the nominal tractive effort was raised to 31,625lb (14,345kg). That made Collett’s ‘new’ Star, or Castle, the most powerful in the UK. The following year the GWR proudly displayed No. 4073 Caerphilly Castle, which emerged from Swindon in 1923, alongside no less than the Flying Scotsman at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley.

Collett argued successfully that had the 19½-ton axle-loading restriction of the Castles been raised to 22½ tons, an even more powerful engine could have been produced. GWR general manager Sir Felix Pole gave the green light for the Kings to be produced, and the first, No. 6000 King George V, appeared from Swindon Works in June 1927.

At 136 tons, the Kings were the heaviest 4-6-0s ever to run in the UK, and at 40,300lb (18,280kg) also had the highest tractive effort of any of them. Their weight meant that they were restricted to certain routes, but they certainly captured the public’s imagination and reinforced the image of the GWR as ‘God’s Wonderful Railway’. They were the ultimate development of Churchward’s 4-cylinder express design.

Better Swindon workshop methods and practices brought in by Collett reduced manufacturing costs, again while improving the performance of Church-ward’s designs, which he turned from machines of raw power to ones of precision with greater potential for power. He did not, however, always take Churchward’s developments to the theoretical next stage of development. Churchward was said to have been dismayed by Collett’s decision in 1924 to rebuild The Great Bear as a Castle, No. 111 Viscount Churchill.

Collett could have followed the lead set by his counterparts on the LMS, Sir William Stanier, and Sir Nigel Gresley on that company’s arch rival the LNER, who developed the Pacific concept. The latter built the A4 streamliners, including No. 4468 Mallard, which on 3 July 1938 became the fastest steam locomotive in the world of all time, reaching 126mph (203km/hr) on a test run on Stoke Bank in Lincolnshire, and beating the 124.5mph (199.5km/hr) record set by the Germans two years before.

Had fate taken a different but wholly logical course, the GWR might well have chosen to go down the William Stanier rather than the Charles Collett route. In 1891, Stanier followed his father into Swindon Works, starting as an office boy and working his way through the workshops, the drawing office, spells as inspector of materials and as assistant to the London Division locomotive superintendent and then works manager in 1920.

In autumn 1931, the LMS asked Stanier to become its chief mechanical engineer, to design modern and far more powerful locomotives. He used his vast knowledge gained at Swindon to produce the Royal Scot and the streamlined Princess Coronation Pacifics, as well as the hugely successful ‘Black Fives’ and 8F 2-8-0s. The GWR could easily have appointed Stanier to succeed Churchward, but instead they chose the Collett way of ‘conservatism with attitude’. Critics both in his time and afterwards have argued that Collett’s adherence to Churchward designs rather than coming up with major new ones of his own led to the GWR locomotive fleet losing its superiority to others.

Two striking and very distinctive but different outlines of classic British steam traction, together at Didcot on 25 May 2009: on the left is 57XX No. 3650, next to visiting LNER A4 streamlined Pacific No. 60007 Sir Nigel Gresley, an example of the world’s fastest steam-locomotive type. FRANK DUMBLETON

Who knows what would have happened if Stanier had been persuaded to stay at Swindon? Would the GWR have had the world’s fastest locomotives in its fleet? I doubt it, because Stanier’s Pacifics were developed in rivalry with those of Gresley on the LNER, in a renewed race to see which company could reach Scotland from London in the shortest time. Without that impetus, Stanier would probably not have done much, if any better than Collett’s Castles and Kings, which are not bad machines at all for a man criticised as having no big ideas of his own. And we would probably not have had the brilliant little workhorses that were Collett’s modern 57XX panniers, and the sister classes that he and his successor Frederick Hawksworth introduced.

A New Breed of Tank Engine

Charles Collett not only applied his innovative rather than inventive approach to powerful express locomotives, but he also developed new engines to suit every requirement, big and small.

The Railways Act of 1921 facilitated the grouping of most of the smaller railway companies into Britain into the ‘Big Four’. Only the GWR retained its pre-grouping identity, the others being the LMS, LNER and Southern Railway, all of which were new creations, umbrella clusters of smaller companies. At the grouping, the GWR acquired twenty-eight companies and also the smaller concerns that they had themselves earlier absorbed. A big gain saw many Welsh railway companies enter the Swindon portfolio, including those that served the valleys, with their lucrative coal traffic.

Last of the Summer Wine: Compo (the late Bill Owen), one of the stars of the BBC’s longest-serving comedy series, inspects the finer points of a 57XX pannier No. 5775 on the Keighley & Worth Valley Railway. KWVR ARCHIVES

When the grouping was completed in 1923, the GWR found itself with a motley collection of tank engines built to different designs, shapes and sizes, flying in the face of any attempt made to standardize the overall locomotive fleet. The problems were clearly evident. It would be hardly economic to introduce a plethora of local service regimes to maintain a ‘Heinz 57 varieties’ collection of non-standard engines, many of which were at their sell-by date or beyond it. The GWR’s own tank engines were by that time also showing their age. Collett saw that he had to address the problem urgently by designing a new standard locomotive to replace them all: enter the 57XX pannier tank.

Officially designated by the GWR as ‘light goods and shunting engines’, they quickly proved that they were capable of handling much more, and took turns at branch and suburban passenger trains, pilot work and even heavy freight. In short, they turned out to be just as much a masterpiece in their own field as the Castles and Kings, and although small by comparison, they were one of the great classic British locomotive designs of all time. However, while the class made an immediate and resounding impact as robust and sturdy workhorses, with large numbers operating from sheds throughout the GWR system, the basis of the design was anything but new.

Again, Collett was no Churchward, but a man who looked back in time rather than to the future, taking established designs and refining them to perfection.

In this case, the ancestry of the 57XX pannier could be traced back through a succession of designs way before Churchward, to locomotive designs as long ago as 1864, when the GWR was still well within the broad-gauge era!

CHAPTER THREE

THE ANCESTRY OF THE 5700 CLASS