35,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

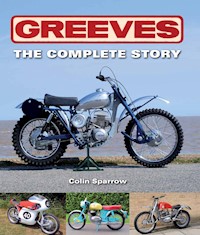

In twenty-five years, Greeves produced around 25,000-30,000 machines - a number considered relatively modest when compared with some of their contemporaries, such as Triumph. However, Greeves was not small in ambition, or indeed achievement, which is resoundingly illustrated in this new book. From a tentative start in the early 1950s, Greeves expanded through the 1960s, producing scrambler, trials, road racing and road bikes. Founders Bert Greeves and Derry Preston Cobb produced machines from their factory at Thundersley in Essex, establishing a world-wide reputation in motorcycle sport, particularly off-road competition. Greeves - The Complete Story gives a detailed history from the early 1950s to the 1970s. With production histories and specification details for all the main models, and hundreds of photographs throughout, it is the ideal resource for anyone with an interest in these classic sporting motorcycles. The book covers: Bert Greeves, Derry Preston Cobb and the formative years - from invalid carriages to motorcycle production in 1953; model-by-model specification guides for the main roadsters, scramblers, trials bikes and road racing bikes; world-wide motorcycle sport success, including European Championship wins for Greeves scramblers in 1960 and 1961; the final years - 1972-1979; and advice on owning and restoring a Greeves model today. Superbly illustrated with 299 colour and black & white photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 402

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

THE COMPLETE STORY

Colin Sparrow

First published in 2014 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Colin Sparrow 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission inwriting from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 741 0

Frontispiece: Oscar Bertram Greeves MBE

CONTENTS

Dedication and Acknowledgements

Introduction

CHAPTER 11906–1950: BEGINNINGS

CHAPTER 21951–1953: MOTORCYCLE EXPERIMENTS

CHAPTER 31954: GREEVES MOTORCYCLES INTO PRODUCTION

CHAPTER 41955: MOTORCYCLE RANGE EXTENDED

CHAPTER 51956: STRUGGLING FOR SALES

CHAPTER 61957: MAKE OR BREAK YEAR

CHAPTER 71958: MARKET REPOSITIONING BRINGS SUCCESS

CHAPTER 81959: GREEVES IN THE ASCENDANT

CHAPTER 91960: EUROPEAN CHAMPIONS

CHAPTER 101961: CHAMPIONS AGAIN

CHAPTER 111962: GREEVES IN THEIR PRIME

CHAPTER 121963: GREEVES AT THEIR ZENITH

CHAPTER 131964: THE CHALLENGER

CHAPTER 141965: COMPETITION ORDERS PREVAIL

CHAPTER 151966: THE ANGLIAN

CHAPTER 161967: THE 360 CHALLENGER

CHAPTER 171968: ENGINE CRISIS HITS GREEVES

CHAPTER 181969: THE GRIFFON

CHAPTER 191970: THE PATHFINDER

CHAPTER 201971: THE CLOUDS GATHER

CHAPTER 21AMERICAN PERSPECTIVE: NICK NICHOLSON MOTORS

CHAPTER 221972–79: THE FINAL YEARS

CHAPTER 23GREEVES IN TODAY’S WORLD

Appendix I: Greeves Models 1954–77

Appendix II: Greeves and the International Six Days Trial

Index

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to the memory of my late wife, Pat Sparrow, in gratitude for a lifetime of companionship and support.

Patricia Sparrow, 1946–2012.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I must first express my thanks to the Chairman and Committee of the Greeves Riders Association for their help and encouragement in the writing of this book and for allowing me full use of their extensive archive of Greeves-related material.

I would also acknowledge the contribution of Andrew King, who assembled much of that material originally, and of Chris Goodfellow, who saved many irreplaceable records and photographs from destruction when the factory closed down. The Kingston Museum and Heritage Service was most helpful with finding accounts of wartime incidents in Surbiton, while Forces War Records enabled me to discover the service record of Flight Sergeant Gordon Greeves. From the Speed Track Tales website came information on ISDT results.

Many friends and acquaintances with an interest in Greeves have provided invaluable assistance by allowing me to photograph their prized motorcycles, allowing me to spend time with them gathering information and responding to my phone calls and emails digging for information or yet more photographs. These individuals include (and apologies to anyone I have missed out):

Dave Bradley, Spike Broadhead, Bill Brooker, Robert Brown, Ron Burton, Rob Carrick, Brian Catt, Scott Chap-pell, Steve Chappell, Rob Clarke, Bert Clements, Dave Deacon, Colin Dennison, Dick Dunkley, Reg Everett, John Fryatt, Chris Goodfellow, Ann Griffin, Dave Harper, Shaun Harvey, Dave Hemsley, Tammy Lyn Johnson, Barry Keymer, Lloyd Lingelbach, Eric Miles, Maurice Nicholas, Mike Norris, Brian Parkinson, Dave Pink, Peter Pluck, Jeff Newton, Peter Smith, Kelvin Sparrowhawk, Ian Stevenson, Ian Stonebridge, Kenny Sykes, Carol Thatcher, Mike Tizard, Mick Wall.

The illustrations were taken by the author or his family and friends unless otherwise stated. The historic photographs come from the GRA Archive. Many of those are official factory photographs or originated from Bert Greeves himself. Many thanks to those who have allowed me to use their images; apologies again to anyone I have overlooked.

INTRODUCTION

It was in 1951 that Bert Greeves and Derry Preston Cobb, founders of the Invacar Company and makers of invalid carriages for the Ministry of Health, decided to diversify into motorcycle manufacture as a precaution against their Government contracts drying up. By 1954, they had started motorcycle production in a new factory in Thundersley, Essex, making road, trials and scrambles bikes. A unique and distinctive feature of Greeves motorcycle frames was the robust alloy down beam that was used on almost all models until the end of the sixties. Sales at first were slow, but a boost came when they were joined by renowned rider Brian Stonebridge as development engineer. Stonebridge revised the competition machines and Greeves started to carve out a reputation in off-road motorcycle sport.

After Stonebridge’s death in a road accident in 1959, his development team carried on to provide the machines on which works rider Dave Bickers won the 250cc European Moto-Cross Championship in 1960 and 1961. Bickers was their most successful rider amongst a galaxy of great competitors, taking Auto-Cycle Union (ACU) 250 Scrambles Stars for the factory on five consecutive years.

Greeves made some very attractive roadsters. They were lightweights mostly powered by Villiers engines. Competition developments were passed on to them, so they were always very good handlers. The company’s twin-cylinder models were particularly pleasant machines to ride.

In 1963, Greeves put a 250cc road racing machine into production. Intended as an inexpensive clubman’s mount, it nonetheless succeeded in winning the Lightweight Manx Grand Prix in 1964 and 1965 and numerous short-circuit races. Previously dependent upon bought-in engines, by 1964 the company was manufacturing its own power unit for their successful Challenger scramblers and Silverstone racers.

The trials bikes, too, were continually improved under the influence of top rider Don Smith. Smith won the European Trials Championship in 1964 and 1967 on Greeves machines. Always near the front in trials, they were a leading influence in the move from big 4-strokes to lighter 2-strokes during the sixties. In 1969, after years of trying, Bill Wilkinson won the Scottish Six Days Trial (SSDT) for Greeves.

Greeves’ focus throughout the 1960s was mainly on off-road competition machinery and with their ever-increasing reputation for success the bikes were to be seen in numbers in the International Six Days Trial (ISDT). Greeves machines were included in one or more of the British International Trophy or Silver Vase teams in every year of the sixties. Altogether, forty ISDT Gold Medals were won by Greeves riders.

Greeves would have liked to sell more roadsters. Bert Greeves understood perfectly well that the market for road bikes dwarfed that for competition machines. But he was equally aware that the battle for orders in the road-bike environment was far fiercer than in the specialized world of competition bikes. Time and again Greeves came up with attractive road models in the hope of making a breakthrough into the road-bike market, for that was where big turnover and profits would lie. They were, however, caught in two dilemmas. Their competition success boosted demand for the trials and scrambles bikes, with the result that development and production capacity was forced to focus on them. At the same time, the company’s profits were insufficient to reinvest in any sizable increase in that capacity, so it might have had difficulty meeting demand had sales of the road machines taken off.

Greeves was never a high-volume producer. The factory records for motorcycles dispatched to dealers in the UK still exist and show a total production of around 15,000 machines for the domestic market. Always an enthusiastic contributor to the post-war export drive, in the mid-1960s at least half of production was going abroad, mostly to the USA, where there was a particularly strong demand for Greeves motocross machines. Unfortunately, the export records were lost when the factory closed, so there is no way now of knowing exact production numbers. An informed estimate of the total number of machines produced is somewhere between 25,000 and 30,000. To put things into proportion, this is about the same as one year’s production by the Triumph Motorcycle Company in the 1960s.

The Greeves model history is convoluted and complex. Greeves’ policy of continuous improvement meant that changes could be introduced mid-year or even from batch to batch. There was always an interrelationship between the various models; an improvement to the scrambler could, if it worked, find its way into the following year’s trials or even road bike. New models would sometimes be introduced during the year, although major launches were usually planned for the autumn motorcycle show.

For the purposes of this book, the models for each year are largely described as they would have been offered at the start of the calendar year in question, with substantial mid-year changes or introductions dealt with in the text. The included specifications have been consolidated to cover the years of production of a particular model and to enumerate the important changes. Space does not permit individual specifications for every model for every year. Although many of the colour photographs are of pristine, carefully restored motorcycles, some are unre-stored and some are still in competition use and have been modified. The photographs are intended as a guide, but anyone contemplating a restoration would be well advised to undertake more research – the information is out there.

Sometimes a few examples of one year’s new model were sold in the latter part of the previous year or examples of machines that had ceased production remained to be sold at the year’s end. For these reasons it is impossible to be dogmatic about any model’s exact time frame – although for machines sold in the UK, the factory dispatch record held by the Greeves Riders Association can be invaluable for tying down a specific machine.

As the reader will have gathered by now, following the Greeves timeline has been a complex undertaking. Many enthusiasts will have more detailed knowledge than I possess about one aspect or another of the Greeves story, or of one or other Greeves model. I make no apology for that; there is only space for so much detail. What I have done is to rely almost exclusively on contemporary sources and on my own observations.

As the reader is entitled to expect, I have tried to avoid guesswork or the making of assumptions. I have also done my best to avoid errors; for any which may have slipped in, I do indeed apologize.

The author with his 32DC Sports Twin on the Isle of Man.

CHAPTER ONE

1906–1950: BEGINNINGS

The story of Greeves motorcycles is inextricably linked to the story of the founder of the marque, Oscar Bertram Greeves, so first we need to look at the early history of the man himself. Known to his contemporaries as ‘Bert’ and often referred to as ‘OBG’, to those who worked or rode for him he was ‘Mr Greeves’. As the founder, owner and managing director of a very successful company, his style could appear autocratic; Bert was always the boss. This, of course, was only natural; he was a man of the mid-twentieth century and in those days that was how bosses expected to operate.

With the confidence of being in charge of his own destiny, he possessed the drive needed to ‘make things happen’. As a trained engineer he understood technical issues and innovation. As a businessman he was able to identify saleable products and successfully put them into production. These qualities, coupled with his enthusiasm for his creations, sketch a picture of a complex, capable and self-reliant man who was equally at home negotiating substantial contracts with Government departments and component suppliers as he was involving himself in the minutiae of technical development.

A lifelong enthusiast, Bert Greeves with his Norton in the 1930s.

There must have been a deal of compassion about him, too. This is evidenced by the main product to which he dedicated his career – independent mobility for the disabled. Although devising ingenious and reliable control systems to suit individual disabilities exercised his technical talent, the need to appreciate properly the needs of the disabled required him to get close to his customers and the realities of the physical difficulties they faced.

This brings us to the other key player in the Greeves/Invacar story – Derek Preston Cobb. ‘Derry’, as he was universally known, was Bert Greeves’ cousin. He had been born with severe disabilities and, being unable to walk, he was dependent upon a wheelchair; he also had no use of his left arm or hand. These handicaps could not hide his spirit and ability though. The ever-cheerful Derry was the successful Company Secretary and Sales Director throughout the firm’s existence.

FORMATIVE YEARS

Bert Greeves was born on 5 June 1906 in Lyon in France to English parents, William and Clara. He was the eldest of their four sons. His father was a consultant to the leather tanning industry. In 1913, as war clouds gathered over Europe, the family moved to England, where William’s tanning expertise was in demand. Schooling for Bert started in England at Worcester Royal Grammar School; three years later, he transferred to Warwick School. As a mechanically minded child, he was fortunate in that the school boasted a comprehensive engineering course and had the facilities to match.

On leaving school in 1922, Bert started an apprenticeship at the Austin car factory in Longbridge. Bert’s lifetime interest in motorcycles was kindled around this time, when he was given a 225cc James by a friend of his father, Billy Badger, who was Chairman of the James concern. However, William Greeves thought that his eldest son’s future should be in leather tanning, not engineering, so before long Bert moved back to Worcester. Not to be denied an engineering career, though, Bert soon took up a further apprenticeship, this time with Heenan and Froude, constructional engineers and makers of dynamometers.

Motorcycling continued, this being Bert’s main form of transport in the 1920s, and culminated in a tuned CS1 Norton. Long-distance touring was undertaken on the Norton, while the machine was also used to take part in motorcycle speed events. In later life, this enthusiasm was to continue, for besides undertaking motorcycle manufacture, Bert would have a sizable collection of veteran machines and a couple of Vincent Black Shadows.

THE RAEBURN GARAGE, SURBITON

By the time Bert finished his apprenticeship, it was 1930 and the depression was just starting to bite. There were few jobs to be had and even the tanning industry was suffering. Bert decided to start up his own business in partnership with his younger brother, Wilbur. In 1931, the family sold up in Worcester and bought a plot of land in Raeburn Avenue, Surbiton. 1932 was taken up by Bert and Wilbur physically building their new garage. The brick façade, with its hints of art deco design, can still be seen today and steel frame construction was used for the workshop to provide a clear working area. With petrol sales and general car repairs, the Raeburn Garage developed and expanded into a successful little business.

The Raeburn Garage in Surbiton as originally built.

During the 1930s, Derry Preston Cobb was also living in Surbiton and the cousins often met. On one occasion, just before the war, Bert thought he would try to help disabled Derry to get about independently. The result was the fitting of a lawnmower engine to Derry’s wheelchair. This idea worked for local trips and resulted in Derry making a tongue-in-cheek half-crown bet with Bert that he could make something better. Derry’s mother lived in Westcliff-on-Sea in Essex, well beyond the range of the electrically powered conveyances of the time. Derry, frustrated at not being able to visit her as often as he would like, fancied something more powerful.

Bert took this challenge seriously and started to think about a design for a petrol-engined invalid carriage. His musings were interrupted by the outbreak of World War II. By 1939, the Raeburn Garage had evolved and expanded into an efficient engineering workshop, sufficiently well-equipped to be able to take on war work. The concern was awarded a Government contract to machine bronze cylinder heads for a compressed-air starter for aero-engines. With the reduction of demand for car repairs as vehicles were laid up and lower petrol sales because of wartime shortages and rationing, the Government work was a lifeline. It did still leave Bert enough time to evolve his invalid carriage design, however.

DERRY PRESTON COBB

Derek Preston Cobb, ‘Derry’, was the man for whom Bert Greeves built the very first Invacar. He was Bert Greeves’ first cousin – their mothers were sisters. Although severely disabled from birth – he was paraplegic and had no use of his left arm or hand – Derry was a remarkable character, unfailingly cheerful and with a great zest for life. His great passion was jazz music and he was regularly to be seen in the London jazz clubs of the day.

When the first Invacar proved a success, Derry unhesitatingly joined Bert Greeves in setting up the new Invacar Ltd. As an astute and active businessman, despite his confinement to a wheelchair and some speech difficulties, Derry made an outstanding contribution to the success of Invacar and Greeves alike. He remained a key part of the firm as Company Secretary and Sales Director for nearly forty years. It is important not to overlook his significance in the Greeves story. His enthusiasm and acumen were part of what made Invacar and Greeves what they were.

Derry took a great interest in the motorcycle side, especially the competition aspect, and would attend many of the local scramble meetings that Greeves supported. His fascination with fast vehicles extended also to his own transport. He was delighted with his first conveyance, the prototype, JPJ 132. In those days, before adapted motor cars became the norm for drivers with physical disabilities, it was the best available and in its lifetime it covered more than 40,000 miles (64,360km).

Cheerful as always; Derry Preston Cobb in 1968.

Derry with long-term steed EHJ 19.

When the Mark VIII came out in 1952, Derry had to have one, and thus was born the notorious (at least to the local constabulary) EHJ 19. Throughout its long life this machine always seemed to acquire the latest motocross engine from the Greeves competition shop, boasting in succession Vale-Onslow, Greeves alloy and Challenger cylinder barrels. It eventually ended up with 25bhp and 70mph (113km/h) potential. With tiller steering!

Derry was well known for exploiting that potential. He had a reputation for fast cornering and regularly inverted the thing. He rarely came to a great deal of harm, but he was of course usually trapped underneath it. Invariably, he would greet his rescuers with his irrepressible chuckle.

The final tale of Derry’s souped-up Invacars is from 1981. By that time, Derry was driving the latest Invacar, the fibreglass-bodied Model 70. It was powered by a (tuned) 500cc Steyer-Puch 4-stroke flat twin. Elmsleigh Engineering, which had taken on Invacar servicing for the south-east, had Derry’s Model 70 in with an engine problem. Derry was delighted when they volunteered to install the similar 650cc version of the engine from Steyr-Puch’s all-terrain vehicle, the Haflinger. Sadly, Derry was to pass away while work was in progress and he never actually saw it.

THE FIRST INVACAR

The three-wheeled single-seat vehicle that emerged in 1941 had a straightforward tubular steel frame and pressed-steel girder-type forks. The offside rear wheel was driven by a 125cc Villiers 2-stroke engine. With the engine mounted on the right, driver access from the kerb side was straightforward. The real ingenuity was apparent in the control arrangements – the vehicle could be driven with one hand. When tested, the one-off conveyance, which was named the Raeburn Invacar, proved to have adequate performance and range and to be perfectly suitable for its intended occupant, Derry Preston Cobb.

Bert and Derry could see that in the Invacar they had a potentially marketable product. In 1942, they patented the design (in particular the control systems) and registered a new company, Invacar Ltd, with Bert and Derry as Directors. Of course, going into production was impossible with the war still on, but Derry continued to use the Invacar and his experience helped in refining the design.

Bert, Derry and the very first Invacar, early 1942.

1943 bomb damage to the rear workshop of the Raeburn Garage.

In company with many, the wartime period was not kind to the Greeves family. Bert’s brother Gordon was killed in December 1940 when the 49 Squadron Handley Page Hampden he was piloting was damaged by flak over Ostend and came down in the sea. Brother Wilbur was called up in 1941, leaving Bert to run the garage and the wartime contracts on his own. In 1942, their mother died, leaving the garage to Bert and Wilbur (their father William had died in 1936). In March 1943, a parachute mine burst nearby, causing damage to the roof and cladding of the garage, but thankfully without any injuries. These events left Bert with a decided antipathy towards all things German.

As the war came to an end, it was time to put plans into action. The Raeburn Garage was sold, with the proceeds split between Bert and his brother. Wilbur had no interest in invalid carriages and departed to start his own garage. Derry wanted to move in with his mother in Westcliff-on-Sea and as Bert no longer had any real ties to Surbiton, they looked for premises in Essex.

THE MOVE TO ESSEX

Although this book is about Greeves motorcycles, the significance of the Invacar in the story must not be overlooked. As a design, the Model 12 Invacar was well ahead of its rivals and can fairly be recognized as the progenitor of all post-war invalid cars. Because it was the right product at the right time, it was astoundingly successful. This success, which would continue for the next twenty-five years, provided the solid financial basis essential for the motorcycle operation.

In 1946, Invacar Ltd set up at 57 West Road, Westcliff-on-Sea in Essex. The 4,000sq ft (372sq m) premises had been the vehicle maintenance workshop for Lord Rayleigh’s Dairy. A modest workforce was recruited and by March 1947 production of the Invacar was under way. At this stage, the vehicles were manufactured for private sale and were continually improved and refined. They were built up individually on waist-high stands, four at a time; there was simply not the space for a production line as such. They sold reasonably well because the demand was there, they did the job and there were few rival products.

To the modern eye, the Model 12 Invacar seems incredibly crude. But this is to overlook the ingenuity, the simplicity and the ruggedness of the machine. The controls could be supplied to suit the particular disability of the purchaser, so the 12S (two-hand control), the 12R (right-hand control) and the 12L (left-hand control) were available to order. The basic control was a steering tiller with a twist-grip and clutch lever. Downwards pressure on the tiller applied the brakes and all the other controls were hand-operated and accessible. All models were powered by a 125cc Villiers engine with 3-speed gearbox. At 30–35mph (48–56km/h) maximum it was fast enough for 1940s traffic and gave economical 80–100mpg (3.5–2.8ltr/100km) fuel consumption.

The Invacar workforce outside 57 West Road, Westcliff-on-Sea, in about 1948.

Invacar assembly at West Road.

With the advent of the National Health Service, the Government was looking seriously at providing independent transport for those with disabilities, including of course the many disabled ex-servicemen returning from the war. The Invacar fitted the bill, so in 1949 Invacar Ltd was able to tender successfully for a Ministry of Health contract to provide such transport. An order for 1,000 units was placed with Invacar, with further large contracts to follow. With this huge increase in orders, it was clear that a larger factory was required.

THUNDERSLEY

Invacar acquired an 8,000sq ft (744sq m), purpose-built premises with ample room for expansion on the Manor Trading Estate off Church Lane, Thundersley, Essex. This new industrial development was about six miles from West-cliff-on-Sea and the company moved there early in 1950.

With the greatly increased scale of operation anticipated, 1950 was taken up with laying out the factory, getting production started and building the management team. The nucleus was those who had come from West Road, in particular Works Manager John Ralling, Draughtsman and soon-to-be Assistant Works Manager Roy Halls, Progress Manager Tony Cobb (Derry’s brother) and General Foreman, later Service Manager, Ted Cotgrove. Plus Bert and Derry, of course.

The Thundersley factory starts to take shape.

Invacars were soon in full production at the new factory.

The spacious new Invacar assembly shop.

Invacar production got under way, although the working practices remained unchanged; they were simply expanded into the new space available. Possibly at this early stage, and after acquiring the Thundersley site, there was not the spare capital to invest in much new machinery and equipment. They were able to fulfil their contracts, however, and Invacar became a highly profitable operation.

Bert Greeves had been advised by the Ministry not to allow his company to rely entirely on Government contracts, but to look round for other work that would serve to keep the factory going if the invalid carriage contracts dried up. By 1954, they felt they had the capacity to take on small light-engineering contracts for outside firms, so advertised their ability to do so.

Invacar transport department.

JOHN RALLING

John Ralling, an engineering graduate from Cambridge University, played a significant role in the success of both Invacar and Greeves. He started with Invacar when they were still at Westcliff-on-Sea and was a key figure in organization and technical development after the move to Thundersley.

Appointed Works Manager at Thundersley, he remained very much ‘hands on’ in those early days. Aware of contemporary foundry practice, he realized that there was a role for alloy castings in the construction of the Invacars. Almost as a hobby, he started experimenting with making castings from scrap aluminium in the garden of his mother’s house in Leigh-on-Sea. This gave him the practical know-how to suggest to Bert Greeves the setting up of a foundry at the new factory. Working with Jock Morrison, an experienced and knowledgeable foundry worker who had just joined the company, they developed the Invacar foundry into a well set-up operation, able to turn out work of high quality. As time went by, new techniques such as shell moulding were adopted with great success.

Later, Ralling took a similar interest in the use of glass-reinforced plastic (fibreglass) in motor vehicle construction. Techniques were still in their infancy, but again by hands-on experimentation, Invacar emerged as able to make fibreglass bodywork and components to a very high standard.

John Ralling was a key member of the Invacar management team. In this 1965 picture they are (from left): Tony Cobb, Bert Greeves, Derry Preston Cobb, John Ralling and Roy Halls.

Of course, above all, as Works Manager, Ralling must be credited with a central role in successfully creating and running a factory capable of turning out the number of Invacars required in order to fulfil Ministry contracts. In June 1965, he was appointed to the Invacar Board as Engineering Director.

One of Bert’s interests was sailing, so he looked into producing a sailing dinghy. Under the name ‘Powered Sails’, the timber dinghy was offered as a pure rowing boat, motor boat, sailing dinghy or motor sailer. Power for the motorized versions was a 1½hp outboard motor. The dinghy came fully equipped and complete with a towing/launching trailer and a waterproof cover. It was actually quite a nice concept – the purchaser genuinely had everything he needed, apart from clothing – to get out on the water. A prototype was built and tested (of course) by Bert Greeves.

At the same time, with his lifelong interest in motorcycles, Greeves also thought that motorcycle manufacture might be interesting and possibly a profitable area to explore …

‘Powered Sails’ – the Greevesfamiiy enjoying the prototype.

CHAPTER TWO

1951–1953: MOTORCYCLE EXPERIMENTS

So, motorcycles it would be. With five years’ experience of Invacar manufacture to draw on and the splendid new factory in Thundersley, Bert and the team knew what they needed to do. The first step was to decide what sort of motorcycle they wanted to make and thought they could sell. To manufacture their own engines and gearboxes would have required far too much investment for what was essentially a sideline, so proprietary engines would need to be used. They were using Villiers engines for the Invacar and already had a commercial relationship with that company. It made good sense in that case to develop the new motorcycle around power units from the Villiers concern.

A small-capacity lightweight machine was settled on. Fabrication of the frame from steel tubing seemed to be straightforward enough and items like hubs and rims could be bought in. The company was developing a form of rubber suspension for the front forks of the Invacar that had already been tried on an old Model 18 Norton.

The long-suffering Model 18 Norton fitted with prototype trailing link forks.

The Greeves rubber suspension system employs Metalastik rubber bushes to connect the sprung and unsprung elements at their pivot point. The bushes are bonded internally and externally so that movement of the suspension produces a twisting effect on the rubber itself. In other words, the rubber is ‘in torsion’. It is this twisting that produces the springing effect. In the experimental machines the rubber bushes were used without any form of damping; it was thought that the natural characteristics of rubber as a springing medium would essentially be progressive and self-damping.

THE FIRST PROTOTYPES: XP1–XP3

Experiments got under way. The trailing link fork already existed, so frame construction started and, in February 1951, the very first Greeves motorcycle emerged. This was designated XP1 (Experimental Prototype no. 1).

On the track behind the factory, the Norton, fitted with a box sidecar and prototype forks, is subjected to cheerful but rigorous testing. Bert Greeves is at the helm.

Ted Cotgrove carries out adjustments on XP1, the first prototype.

The frame consisted of double top tubes of 2in (50mm) steel, one above the other and triangulated on to the top and bottom of the steering head. To this were attached two 1in (25mm) steel down tubes mounted side by side that were curved to pass under and support the engine and then upwards to meet the top tubes and again backwards in a loop to support the seat. The frame was without lugs, so the tubes were joined by bronze welding. Wheels, brakes and so on were conventional and a steel fuel tank was fitted.

The most novel feature of the new bike was of course the suspension. The front fork stanchions kicked out forwards and supported a trailing link arrangement with a steel loop passing over the front of the wheel. It then carried back past the stanchions to support the wheel in line with the fork yokes. At the pivot point for the trailing link was the suspension medium itself; a pair of Metalastik rubber bushes that came under torsion as the trailing arm deflected under load. The rear suspension used a swinging arm with floating struts connected to lugs that rotated around Metalastik bushes mounted beneath the seat.

As the company had laid out an off-road test track on yet to be developed ground behind the factory, XP1 was constructed as a scrambler. The engine was a 122cc Villiers 10D 2-stroke single and used an Amal 275 carburettor mounted horizontally. After initial testing in which Bert himself liked to take part, XP1 was entered in Eastern Centre scrambles, ridden by Fred Jessamy, a good local rider. Scrambling being one of the hardest tests to which a motorcycle can be subjected, fatigue fractures of the tubes began to appear, particularly around the steering head and in areas where heat had been applied when welding up. The unfortunate Jessamy was injured at one scramble when the bolt retaining the forks to the steering head broke, causing them to part company from the bike.

There were also braking problems, which seemed to be inherent in the fork layout. One effect of applying the brake was to lengthen the wheelbase as the front dipped; not a helpful effect in an off-road environment. Also anchoring the brake plate was problematic, with the cumbersome anchorage arrangement encouraging vibration.

In May 1951, Bert felt confident enough to invite C.P. Read from Motor Cycling along to try the machine. Read tried it on the off-road test track and was most impressed with the handling and the way the suspension ironed out the bumps. He was also able to remark that nothing broke or fell off. He did say that ‘the appearance of the front end of the Greeves somewhat shook my rather conventional outlook’. Which is a polite way of acknowledging that it was actually pretty hideous.

Shortly afterwards, a 197cc Villiers 6E engine was fitted and various other alterations made. The revised machine was subsequently referred to as XP3, although in essence it was the same motorcycle as XP1. Why XP3? Well, in the meantime another prototype had been built, this time as a roadster. This machine was designated XP2. The twin top tubes used in XP1 were replaced by a single larger-section tube and the trailing link forks were revised, with the link fitted at a shallower angle than on the earlier bike. It had a 197cc Villiers 6E, again with an Amal carburettor mounted horizontally. Undamped rubber in torsion rear suspension was utilized, of course. As originally built, it had deeply valenced steel mudguards and a larger, roadster-type tank. It was not long, however, before they were removed and the machine converted to scrambler trim.

The second prototype, XP2, as originally built up in roadster configuration.

Greeves’ first tank logo.

XP1 REPLICA – AN INTERESTING EXERCISE

The faithful replica of Experimental Prototype 1, the very first Greeves motorcycle.

The very first prototypes, XP1–XP3, were consigned to a watery grave in 1951 after less than a year of life. Newark-based Greeves enthusiast Dave ‘Brad’ Bradley has a collection of early off-roaders, including XP4A, the first alloy-beam prototype. With his interest in early Greeves, he decided to recreate one of the 1951 prototypes. He enlisted the services of ace Greeves restorer John Fryatt and, using the few photographs that exist and the Villiers flywheel cover as a reference, they worked out the size and configuration of the frame.

While John got on with analysing the frame design and the trailing link forks, Brad set about sourcing a Villiers 10D engine, the wheels and all the other parts to assemble a complete motorcycle. When John had bent up and assembled the frame, a trial assembly was made. It all seemed to be fitting together and a strange machine, the like of which had not been seen for sixty years, started to appear.

The result is a faithful replica of a unique motorcycle that existed briefly in 1951. Despite its strange appearance, it actually works quite well. The light weight and good suspension travel means that it is fine off-road. Its use in local scrambles would have been perfectly feasible and it is easy to imagine Frank Byford being reasonably competitive on it.

Dave Bradley with his unique XP1 replica.

The root cause of the constant frame breakages was the poor-quality steel tubing, which was all that was available in that era of post-war shortages. Bert decided that something better was needed. In late 1951, the first two prototypes were dismantled and the remains ceremoniously consigned to a pond at the back of the factory. They had served their purpose; they had shown up the frame problems to be encountered in motorcycle design and had proved the suspension. The trailing link fork design, if not quite right in a motorcycle application, was subsequently used successfully for the Mk 8 Invacar.

GREEVES SIDECAR CHASSIS

Alongside the motorcycle experiments, the company explored a further diversification idea – a sidecar chassis. It was designed with adjustable attachments and body mountings so that it could be attached to any motorcycle and accept any sidecar body. Constructed from 1¾ in steel tubing, it was bronze welded throughout with cast-iron lugs at strategic points. The chassis itself had no suspension, but the body attachments were pivoted at the rear on Metalastik bushes and rubber-mounted at the front, giving a modicum of insulation from road shocks. It had a deeply valenced steel mudguard and a 19in wheel. A small sidelight was mounted on the mudguard.

A two-seat box-like body was fitted on the new chassis and exhaustively bashed around the test track attached to the long-suffering 1930 Norton. A row of concrete kerb stones was even laid out and the sidecar wheel run over them at speed to see if anything broke. Judging by the expressions on testers’ faces in contemporary photographs this process was great fun. Later, the sidecar was attached to the second-generation Greeves prototype motorcycles for continued crude destruction-style testing. The design must have survived the testing, for the sidecar was put into production. Very few were sold, though.

The Greeves sidecar chassis; only a few were built.

THE XP4 PROTOTYPES

The original motorcycle prototypes, XP1–3, having served their purpose, it was time to move on to the next stage. Testing had identified that the key area for failures was around the steering head where the load reversals through the steering head showed up any weakness in the frame joints or the tubing. Thought was given to ways of reinforcing the steering-head area, but all the designs in steel that the team came up with involved complex manufacturing procedures and added weight.

Next, the use of aluminium alloy was considered. Invacar had developed its own aluminium foundry and was producing quality cast-alloy components for the invalid carriages. The use of cast aluminium for key elements of motorcycle frames was new ground in the 1950s. The company was on its own trying to do this and was virtually starting from first principles. Alloy tube would not be strong enough, but then the team hit on the idea of using an ‘H’ section beam. Calculations proved that such a beam could be amply strong enough without becoming excessively bulky.

THE ALLOY BEAM

The method of construction decided upon was to make a steel top tube, weld it to the steering head and then sandcast the alloy beam around the assembly. This would provide a very robust down-member, while eliminating all the frame joints in the vulnerable steering-head area. Now the team had to work out how to do it.

The aluminium-sprayed steering head with top tube is placed in the lower half of the shell mould. Once the halves have been clamped together, the molten metal for the alloy beam will be poured.

After careful thought, LM6 alloy was chosen as it was already a stock alloy, with suitable melting and casting qualities. Next, it was necessary to work out how to cast the aluminium on to the steel components. At first, there were constant problems with blow holes in the castings. At the time, sand moulding was being used and it was concluded that moisture from the sand was condensing on the steel insert during the pour. Preheating the insert was tried, but to no avail. The answer, a new technique developed elsewhere and in the nick of time for Greeves, was shell moulding.

In shell-mould casting, the mould is a thin-walled shell created from applying a sand–resin mixture around a metal pattern. The pattern is made in two halves. Each half is heated and then clamped into a dump box, which contains a mixture of sand and a resin binder. The dump box is inverted, allowing the sand–resin mixture to coat the pattern. The heated pattern partially cures the mixture, which now forms a shell around it. The whole is heated in an oven that completes the curing and, once cooled, the patterns are removed. The two mould halves are then clamped together, supported on a sand bed, and the aluminium poured. Upon cooling, the mould is broken and the casting removed.

XP4, the first alloy-beam prototype, has been faithfully restored.

Iron contamination, from the factory environment or from the steel tubing itself, had to be avoided at all costs because it makes the cast alloy brittle. As development advanced, this factor started to cause difficulties. Using only virgin LM6 alloy and taking care in the foundry reduced this issue, but the root problem was iron pick-up from the steel components, with even a trace of rust affecting the casting. The answer was to shot-blast the steel and have it aluminium-sprayed. Developing this process took until mid-1952, but the team got there in the end.

The result of all this toil was Greeves’ alloy beam – an H-section aluminium down-member cast around a steel steering head and top tube. This assembly was then built up with a tubular steel rear frame and cast-alloy engine plates and was fitted with rubber-sprung swinging arm rear suspension of similar design to that used in the earlier prototypes.

Three prototypes were constructed in 1952 using these components. They were known as the XP4s: XP4A (frame no. 52/101); XP4B; and XP4C. They were all built up as scramblers, although XP4A, the first, was soon reconfigured as a trials bike. The engines used were the Villiers 6E (197cc), carried in cast-alloy engine plates that formed the lower part of the frame. The braking problems with the trailing link forks were solved by the simple expedient, which can be credited to Assistant Works Manager Roy Halls, of redesigning them (reversing them) as leading link, using the XP2 fork as a basis. Draughtsman John Collins drew them up, using the fork angle and trail of his own James trials bike as a starting point for the geometry.

More enthusiastic testing. This time, XP4 is coupled to a Greeves sidecar. A grinning Peter Vine acts as ballast for Bert Greeves.

Testing was carried out by Frank Byford, who rode the prototypes with some success in Eastern Centre scrambles and also carried out much of the development work on the machines. Early scrambles soon showed up the lack of damping in the suspension; Byford was described by one observer as ‘bouncing like a ball’ as he came down the bumpy main straight at the Shrubland Park circuit. The pious hope that the natural hysteresis of the rubber bushes would provide sufficient damping was soon to be dashed, at least in motorcycle use, and after experiments by Byford himself, simple friction dampers were fitted, front and rear. (In Invacar use the rubber suspension never did require dampers.)

The team had cracked it! The alloy beam and leading link forks plus friction damping worked and by the start of 1953 the Greeves development team could get on with designing a range of production bikes with the aim of getting them to the Earls Court Cycle and Motor Cycle Show in November. A further contributing factor to the lively ride was discovered to be the short (48in [1,219mm]) wheelbase of the XP4s. The first production models were given a 52in [1,320mm] wheelbase. The alloy beam and the leading link forks were to remain a feature of all Greeves competition bikes (and most roadsters) until the late 1960s.

FRANK BYFORD

Frank Byford joined Invacar Ltd in 1950. An ambitious young man with a sound grounding in engineering, he was almost immediately assigned to work on the new motorcycle. Bert Greeves was responsible for the original concept, but it was up to a small team, most of whom also had roles in the Invacar operation, to turn the concept into metal. Bert had, after all, an invalid carriage factory to run. Development was on a trial and error basis; the factory had the facilities to make the one-off parts they needed. Byford was part of this process, working largely with Roy Halls. He made the first set of leading link forks from Hall’s drawings.

Frank Byford’s major role, of course, was as the rider of the prototypes in scrambles. Fred Jessamy, the original rider, had walked away from the project after the steering-head failure on XP1 put him in hospital. Byford took over, most successfully as it turned out, with some decent results in local events, particularly on the alloy-beam XP4 machines.

With his engineering background, he was able to make improvements as they went along based on the experience gained from competition. Sometimes, however, this brought him into conflict with Bert Greeves, who very much saw himself as leading the project. Frank eventually left Greeves at the end of 1953.

Frank Byford in action on one of the three XP4 alloy-beam prototypes.

CHAPTER THREE

1954: GREEVES MOTORCYCLES INTO PRODUCTION

The public debut of the new Greeves motorcycles was at the Earls Court Cycle and Motor Cycle Show, which was opened by then Foreign Secretary Sir Anthony Eden on 14 November 1953. As a new motorcycle exhibitor, Greeves was allocated a modest area near the main Warwick Road entrance among the push bikes in which to set up the stand. Open on all sides, the Greeves stand displayed four Villiers-engined 197cc machines – two versions of the roadster, a scrambler and a trials bike. On a plinth in the centre was the pride of the range, the 25D Fleetwing roadster, which sported the newly introduced 242cc British Anzani twin. The display was surmounted by a large sign in the shape of a Greeves tank badge. It bore the company’s new logo, the Greeves ‘signature’ device, which was indeed a facsimile of Bert Greeves’ own signature.

At one end was a display of alloy castings for the motorcycles – the front beam, engine plates and battery holder. A motorcycle frame was set up on a stand with grips mounted each side at the rear wheel spindle location. Visitors were encouraged to bounce the swinging arm up and down to satisfy themselves that the unorthodox rubber suspension and adjustable friction damping did actually work.

It is 1954 and a pretty girl smiles from her 20D Roadster De-Luxe.

The factory team with the bikes for the Earls Court Show; John Ralling and Derry Preston Cobb take centre stage.

The Greeves stand at Earls Court, November 1953.

The Earls Court display was well received, with plenty of visitors interested in examining the quirky products of this new factory. With this first model range Greeves was aiming primarily at producing lightweight roadsters. Britain was still struggling in post-war austerity and cars were scarce and expensive. Motorcycles were the personal transport of the working man and Greeves was hoping to tap into this sizable market. The roadsters received a reasonable reception from the motorcycling press. The general conclusion was that they were well built, suitable for their intended purpose and boasted excellent handling. The Villiers engines were well known, of course, and were standard wear for many ‘ride to work’ lightweights. Such minor reservations as were expressed focused on the unorthodox features – the leading link forks, the alloy beam and the rubber suspension – and on the appearance, particularly the sizable gap between the engine and the fuel tank.

THE GREEVES RANGE FOR 1954

On offer for 1954 was a range of five machines, all of which would be classified as lightweights. Three were roadsters, while the other two were designed for off-road competition. With no franchised dealers appointed at this early time, potential buyers were invited to contact the factory direct.

All of the motorcycles in this initial Greeves range shared the same frame, forks and rear suspension. This established from the start the close relationship between Greeves road bikes and their competition stablemates. The frames all featured Greeves’ patented alloy beam and lug-less bronze-welded steel tubing.

Greeves’ first advertisement featured the 20D.

The forks were Greeves’ own leading link design as developed on the prototypes. The front and rear suspension was by means of Metalastik bonded-rubber bushes operating in torsion with resin-bonded friction discs to provide damping. The early machines thus equipped are known now as the ‘friction-damped’ models.