18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

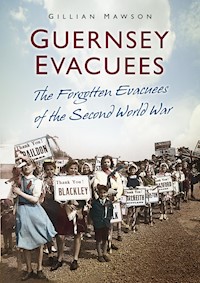

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In June 1940, 17,000 people fled Guernsey to England, including 5,000 school children with their teachers and 500 mothers as 'helpers'. The Channel Islands were occupied on 30 June - the only part of British territory that was occupied by Nazi forces during the Second World War. Most evacuees were transported to smoky industrial towns in Northern England - an environment so very different to their rural island. For five years they made new lives in towns where the local accent was often confusing, but for most, the generosity shown to them was astounding. They received assistance from Canada and the USA - one Guernsey school was 'sponsored' by wealthy Americans such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Hollywood stars. From May 1945, the evacuees began to return home, although many decided to remain in England. Wartime bonds were forged between Guernsey and Northern England that were so strong, they still exist today.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My grateful thanks to the following: the evacuees and their families who have shared their wonderful stories and personal documents with me over the past four years. Please be assured that, should your story not be mentioned in this book, it will be used in many other ways, to tell people of all ages about your wartime experiences. I also wish to thank: my family and friends for their never-ending support and encouragement; Michelle Tilling and all at The History Press; Sir Geoffrey Rowland (Bailiff of Guernsey 2005–12) and Lady Diana Rowland; Deputy Mike O’Hara (Minister of Culture and Leisure, Guernsey) and Teresa O’Hara; Mrs Joan Ozanne and her family; Jim Cathcart, and all at BBC Guernsey; Amanda Bennett and all at the Priaulx Library, Guernsey; Darryl Ogier and all at the Island Archives, Guernsey; Di Digard and all at Guernsey Press and the Guiton Group; The March Fitch Fund, who kindly assisted me with research expenses; Joanne Fitton, Leeds University Archives; Joanne Dunn, Sue Shore, Sue Heap and all at Stockport MBC who have worked with me; Dawn Gallienne, Guernsey Post; Michael Paul and the Guernsey Society; Peter Trollope, BBC Television; Raymond Ashton; Donna Hardman, Bury Archive Service; Derek and Gillian Martel; Dot Carruthers, Elizabeth College Archive; The Second World War Experience Centre; Guernsey Retired Teachers Association; Richard Heaume, German Occupation Museum; Renee Holland; Barbara and Mike Mulvihill; Emily McIntosh; Sarah Yorke, UNLtd; The family of the late Maureen Muggeridge; The family of the late Brian Ahier Read; Professor Penny Summerfield; Julie Anderson; Neil Pemberton; Jean Cooper; Ann Barlow; Linne Matthews; Lisa Greenhalgh; Suzanne Spicer; Debra Dickson; Christopher Thorpe; Alice McDonnell; Val Harrington; Fiona Kilpatrick; Rosemary and Robin Wignall; Caroline and Chris Worrall and my colleagues at the University of Manchester. My apologies to those who are not mentioned here, but who are certainly not forgotten!

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Countdown to Evacuation

2 Finding a New Home

3 Settling into the Community

4 The Kindness of Strangers

5 The Guernsey Schools

6 Countdown to Liberation

7 A Commemoration of the Evacuation

Further Reading

Praise for the Author

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

In 2008 I set out to examine the experience of evacuated Guernsey civilians, and to give these evacuees, who have largely been forgotten by historians, a voice. I was able to interview people in Guernsey, together with many that had remained in England after the war. I was also able to interview some who were young mothers during the evacuation, and their stories were particularly moving. Sadly a great many evacuees had passed away by the time I began my research, research which was very emotional and created close relationships with some of my interviewees. It also led to my involvement in a number of events which marked the seventieth anniversary of the evacuation in 2010, which changed my life completely.

1

COUNTDOWN TO EVACUATION

My childhood was left inside.

when I closed my bedroom door.

In the hall, distraught, father waits, mother weeps.

The dog unaware, wags his tail

and licks the tears from my face.

Reluctantly we speed to the harbour.

The smell of tobacco smoke on

father’s jacket will remain with me.

On the ship we say goodbye, perhaps forever.

I feel empty like a shell.1

On 28 June 1940, at about 6.30 p.m., German aircraft appeared over the island of Guernsey. At the time Valerie Pales was helping her mother to harvest their potato crop, and recalls:

One plane broke away from the others and started machine-gunning our field, we could hear the bullets breaking panes of glass in our glasshouse and were worried that my father was in there, luckily he was in a brick-built shed. My mother hurried me to our house to shelter under the stairs. Father joined us and said that my mother and I would be safer in England, so they packed a few belongings into their car and drove to the harbour.

It was a savage raid, as the aircraft dropped bombs on the pier and town, then swooped down to machine-gun the streets around the harbour, apparently assuming that the tomato lorries lined up at the harbour contained ammunition. Most of the lorry drivers had crawled under their vehicles for shelter, and when the lorries were hit, they were trapped underneath. An RAF Air Ministry report noted a similar attack on the island of Jersey and listed the casualties as follows ‘Jersey: 3 dead, Several wounded, Guernsey: 23 killed, 36 wounded.’2

Private Board of the St John’s Ambulance Brigade arrived at the harbour a few minutes later:

Everything was in chaos, the produce lorries had been transferred into a line of fire … our number 2 ambulance, the best one in the island, was against the kerb, every bit of glass smashed, and the sides and back doors riddled with shrapnel and bullet holes … one patient had been killed as he lay on the stretcher … the attendant was severely injured.

The only defence the island had at the time was a Lewis gun on the Isle of Sark mail boat, which had recently arrived to take evacuees to England. As the air raid commenced, evacuees were still boarding, and Mrs Trotter wrote later:

We had just sat down in the lounge when we heard terrific explosions! 50 minutes of terror followed! I stayed with the children whilst my husband went up top to offer assistance with the Lewis gun. The boat shook and trembled but luckily was not hit. Our guns were the only protection the island had. I later came up to find tomato lorries ablaze on the harbour and some people had been killed.

The raid continued until about 8.00 p.m., at which point the Sark’s Captain Golding asked those around the jetty if they wished to board his boat. The Pales family boarded, along with many others who had suddenly decided to leave the island. The ship prepared to leave Guernsey at 10.00 p.m. with 647 passengers, 200 more than Captain Golding had originally planned to carry. Somehow Valerie Pales became separated from her mother, and as the boat started to pull away, she recalled:

My mother was on the boat, screaming out that she had lost her child. Luckily somebody picked me up after the gangway had been pulled up, and managed to hand me over the ship’s rail to my distraught mother. I believe I was the last child evacuee to leave Guernsey.

Valerie Pales.

In early 1940, the Channel Island of Guernsey was home to around 40,000 people, whose income came mostly from tourism, fishing, horticulture and agriculture. The island is about 30 miles from the French coast, and 70 miles from England’s south coast. In 1940, the majority of Guernsey’s residents were born there, but English people had been drawn to the warmer climate and the opportunities for agriculture. Loyal to the British crown since AD 933, the Channel Islands originally belonged to the Duchy of Normandy, but when William became King of England in 1066, he continued to rule the Channel Islands as Duke of Normandy. The mainland of Normandy was lost to England in the thirteenth century but the islands remained loyal to England’s King John. A British governor had been living in Guernsey since 1486, and the British flag was flown on the island, together with the Guernsey flag. ‘God Save the King’ was Guernsey’s national anthem too, and Joan Ozanne recalls, ‘it was sung before every cinema and theatre show. The inhabitants perceived themselves, not just as residents of Guernsey, but also as British:

If there are two qualities upon which Channel Islanders pride themselves, they are their loyalty and their independence. These qualities they possess in common with all the British race.3

From the moment that Germany invaded France in May 1940, those living in the nearby Channel Islands of Guernsey, Jersey, Alderney and Sark were unsure whether their islands would be attacked or ignored by Hitler. However, in early June, as France began to fall, and British troops retreated to England, French refugees began to arrive in Guernsey’s main harbour, St Peter Port. Fears arose that a German invasion might indeed take place, as the closeness of Guernsey to Cherbourg meant that the island was wide open to attack by German forces both by sea and by air. The Revd W.H. Milnes, the Principal of Elizabeth College, visited the Governor of Guernsey to express his fears that the island might be occupied, and to ask whether any plans were in hand for the evacuation of Guernsey’s schoolchildren, stating later:

Though some of those in authority doubted whether anything should be done, the Governor saw my point and it was agreed that the Procureur and I, should fly to London to arrange the evacuation of the schoolchildren in the Channel Isles.

However, the situation escalated to such a degree that no officials were able to leave the island for London. The Revd Mr Milnes began to assemble equipment for the evacuation of his pupils, realising that ‘an evacuation across the sea was going to be a very different affair from an English evacuation from one county to another.’ At the same time, the fate of the Channel Islands was being debated in London. On 11 June the British War Cabinet considered that Hitler might occupy the Channel Islands to ‘strike a blow at our prestige by the temporary occupation of British territory.’ Winston Churchill found it repugnant to abandon British territory which had been in the possession of the Crown since the Norman Conquest, and felt it ought to be possible ‘by the use of our sea power, to prevent the invasion of the islands by the enemy.’ However, the Vice Chief of Naval Staff advised Churchill that the equipment necessary for the defence of the Channel Islands was not available. The cabinet had two objections to the evacuation of all Channel Island civilians to England. The first was the probability of enemy air attacks on unprotected evacuation ships, the second was the thought that the inhabitants might not be willing to leave. After some deliberation, the cabinet finally decided:

The Channel Islands are not of major strategic importance either to ourselves or the enemy … we recommend immediate consideration be given by the Ministry of Home Security … for the evacuation of all women and children on a voluntary and free basis.

On 16 June, the British Government ordered the removal of British troops from the Channel Islands, believing that they would be put to better use on the English coast. As troops began to leave the islands, this caused some despondency among the population. The government did not provide evacuation plans for the islanders at this stage, as they could not promise them any ships until the evacuation of British forces from France had been completed. On Monday 17 June, Guernsey’s Education Council supported the evacuation of all schoolchildren, should such a course be recommended. On 18 June, the President of the Education Council invited Guernsey headteachers to an emergency meeting, to inform them that the evacuation of schoolchildren was a possibility. That same evening, the sound of guns and explosions on the French coast could be heard in Guernsey, causing some alarm, and the Revd Mr Milnes wrote:

We could hear the explosions from Cherbourg and other places on the French mainland … parents were getting very anxious and my telephone went day and night, so continuously, that I had to employ two helpers to take the calls.

On the morning of 19 June, as the headteachers met to discuss their plans, the bailiff, Victor Carey, arranged an emergency meeting with them. He told them that the British War Cabinet was discussing the position of the Channel Islands, and that the evacuation of schoolchildren would take place on a voluntary, rather than a compulsory, basis. Those present were pledged to secrecy for the time being, but a few hours later, news reached Victor Carey from the British Government that several evacuation ships would reach Guernsey the next day to commence the evacuation of the schoolchildren and their teachers. Guernsey teachers were quickly advised of the evacuation plans, and leaflets were printed for parents, to explain exactly what each child could take in the way of clothing and equipment. That same afternoon a free edition of the Guernsey Star informed parents that if they wished to send their children away the following morning, they should register at their child’s school from 7.00 p.m. that very evening. Mothers with infants and men of military age also had the option to leave the island.

The Revd Mr Milnes assembled his Elizabeth College pupils and Ron Blicq recalls his solemn announcement:

Within a few days Guernsey almost certainly will be occupied by German troops. Consequently, starting tomorrow, the Government plans to bring a fleet of boats to the island to evacuate everyone who wishes to leave before the enemy arrives. I must make it clear that no one has to go. Your parents will tell you whether you are to stay or leave. And they will tell you their own plans … the College has to be ready to leave at any time after nine o’clock tomorrow.

The Guernsey Star evacuation notice.

Ironically several families had recently moved to the island, thinking that Guernsey would be safer than England. Several English boys were sent to Guernsey in late 1939. Thirteen-year-old Kenneth Cleal was sent from London to his father’s family in Guernsey. His parents believed that the war would pass the island by and that Kenneth would be safer there. He attended the Boys’ Grammar School and was evacuated with the school to the Oldham area in June 1940. Just a few months earlier, the Pales family had set up a horticultural business on the island.

Some families’ decisions to evacuate may have been influenced by another article on the front page of the Guernsey Star, which advised islanders that:

Six boat loads of refugees reach St Peter Port; More French refugees, fleeing from the terror of German planes and troops arrived in Guernsey last night … there isn’t a soul left in the town of Cherbourg … as we left, the docks were being blown sky high.

Winifred Best described the view as she had looked out towards the tiny island of Herm:

The whole sky was black like the middle of the night! Mixed with this were flames, Cherbourg was on fire! By 4pm the whole island was in darkness, I will never forget it.

At the time, Jack Martel was in Guernsey on leave, having narrowly escaped Dunkirk where his helmet was dented by shrapnel while wading out to the boats to escape. His sister Marie recalls:

Jack hurriedly brought in my clothes from the washing line and packed them into his kit bag. This later proved a problem, for on his arrival in Falmouth, he and his cousin, Alfred Digard, were arrested as suspected spies for ‘being in uniform and travelling on a civilian boat’, also ‘being in possession of children’s clothing’.

Guernsey parents now had just a few hours to make a crucial decision – whether or not to send their children away to England the next morning. Richard Adey was on the beach when he noticed his mother waving to him in an agitated manner:

‘Quickly!’ she said, ‘Dad’s brought the car and we have to go home immediately.’ Now this in itself indicated a crisis, our car was not used lightly and without due thought, but today it seemed that the world and us with it had turned upside down. All the adults on the beach were talking in a hushed and serious manner.

Rachel Rabey heard her mother and aunt whisphering throughout the night, then at breakfast:

I was told that the school were going on holiday and I could go too. A little suitcase was packed, I still have it with my name hastily painted in white across the lid.

Paulette Tapp was living with her grandmother at the time, and one of the nuns from her school came to announce that the school was to be evacuated:

If only you could imagine her sorrow, and also my aunty and uncle. She packed up my clothes crying. I was not really old enough to understand. I saw everybody crying, so I started to cry.

Some Guernsey parents were concerned for the safety of their daughters and Joanne James recalled ‘my parents had heard stories of rape by German troops in Europe, and were too afraid to leave me in Guernsey so made the decision to let me go.’ Therese Riochet found her mother in the kitchen, with a paper with instructions in her hand, and two labels with her name and address on them:

I asked what they were for, and she answered, ‘You are going to be evacuated with the school.’ Then I asked her why, she said, ‘You heard those guns last night didn’t you … well they were at Cherbourg on the coast of France. The Germans are there and people say they are coming here to Guernsey.’

Some families did not actually see the newspaper report announcing the evacuation. Pamela Blunt’s family knew nothing about the evacuation until an ice cream seller came round in his sidecar at 3.30 a.m., ‘ringing a bell and telling us that the schools were to be evacuted that morning. We left home only a few hours later.’

In his book, No Cause for Panic, Brian Read pointed out that:

There was widespread panic, several farmers slaughtered their cattle unnecessarily and thousands of parents drove to the local veterinary surgery to have their dogs and cats put to sleep.

Muriel Parsons family tried to catch their cat, Nippy, to give him to the vet, but Nippy lived up to his name and escaped over the garden wall. He later returned to the house where Muriel found him ‘sitting in the kitchen, purring and looking pleased with himself – he was caught the next day and then he was – no more.’ One little girl accompanied her mother to the vet, having been told that their cat was to be cared for while they were away. It was several years later when she realised why her mother had been crying as they had driven away from the vet’s office. Mr Godfray recalled ‘at the last moment, my friend, who was coming with us, drove off home to shoot his dog.’ Others simply turned their animals loose as they left their homes, and Anne Misselke recalls:

There were loose cows wandering about and a few cats and dogs … then there was a little kitten running about and suddenly two budgies flew overhead. Well, we had a budgie as well and a kitten, I was worried and said to mum ‘if you go to England, Mummy, you aren’t going to let Happy and Lucky out to fly about and walk about like that are you?’

Animals had recently been killed in England too – in late 1939 the animal-loving citizens of Britain, fearful of carpet bombing, evacuation and food shortages, had begun to put down their pets.5In addition, farmers had culled many of their animals as they were ordered to concentrate on growing more crops to feed the British public.

Many evacuees buried valuables in their gardens, houses were left abandoned with the keys still in the doors, and thousands went to the bank to try to draw out their money. There was a desperate rush to obtain suitcases, but the few shops which sold them soon ran out of stock. As a result, many evacuees left Guernsey with just a few possessions crammed into a pillowcase or a tomato basket. Between 20 and 28 June an estimated 17,000 people left Guernsey, but the first to leave were around 5,000 schoolchildren with their teachers and 500 adult helpers. The children’s parents had received official instructions that:

It will not be possible, on account of the danger of air raids, to permit masses of people to congregate at the habour, and accordingly, parents must say au revoir to their children at their homes or at their schools.

On the morning of 20 June, parents walked their children to the school gates where tearful farewells took place. Muriel Bougourd recalls:

I remember we had to leave home very early and it was dark, my father took me to school on the back of his bike (no cars in those days) [and] we all had to meet at the school. We were then taken on buses down to the harbour. I remember the crowds and darkness, and although it was June my mother had put me in my winter coat and beret. I had a small suitcase; there wouldn’t have been much room for more than a change of clothes. At the very last minute they realised that I had no comb – my hair was long, so my father gave me a small pocket comb.

Rhona Le Page recalls hugging her parents at the gates:

They told me that I was just going for a day out with my school. Yet later, I was confused when two of my friends said that their mum had told them they were going away to England and that they themselves hoped to follow on the next available boat.

Some children saw the coming evacuation as an exciting event in their lives. Margaret Carberry was evacuated with her school, and her mother, and remembers packing her bag:

I think we probably thought it was a big adventure to be going on a boat trip to England; for us it was like going on a holiday and we had never been on a holiday before, I don’t remember being worried about leaving Guernsey. That may have been because my mother was going to be with us.

The promised ships were late in arriving at the islands and Janice Rees recalled the long wait at the harbour for her boat:

First of all standing up holding our belongings, then we put our cases down, till we gradually sat on them. We sat in this attitude for so long that we broke the sides of our cases.

Some of the ships did not arrive and some children actually returned home again, which surprised and shocked their parents. Many could not bear to part with their children for a second time, so unpacked their suitcases and kept them at home. Others endured a very emotional evening, and had to repeat the walk to the school gates with their children the following morning. Arthur Trump was evacuated with the Castel School and recalled:

Although around 50 pupils were evacuated, many more should have gone. We assembled at the school two or three times but it was always cancelled because there were no boats available. By the time we left, half the people who were meant to go didn’t turn up.

One headmaster noted in his diary that, when his school group reassembled, only 134 children arrived out of the 170 who had turned up the previous day. Isabel Ozanne recalls:

I was nine years old, an only child. My friends and teachers all left on buses to catch the boat, but my mum decided to take me back home. I left the next day in the care of two young mothers with babies and schoolchildren. I guess my parents thought that they would keep an eye on me.

Guernsey’s Education Council noted later:

Throughout the evacuation we were greatly handicapped by parents changing their minds. Actually 755 teachers and helpers had registered at the Vale and Torteval Schools but there were many withdrawals at the last moment and we were able to put 76 Alderney children aboard the Sheringham in addition to the local schools.6

Captain James Bridson and evacuees on the SS Viking.

Second Officer Harry Kinley described his experiences as the children began to board the SS Viking:

By 9 a.m. the children were arriving in great numbers and I will never forget the sight of those thousands of children lined up on the pier with their gas masks over their shoulders and carrying small cases. From the age of four to seventeen they came aboard, many of them in tears. It was hard to keep back our own tears I can tell you. We stopped counting the children after 1,800 and with the teachers and helpers, there must have been well over 2,000 on board.

The Viking was completely packed, with every cabin, corner and space filled with children, teachers and helpers. Ron Gould saw his father just before he went aboard, ‘Dad gave me what he had in his pocket, which was a 10s note (50 pence today), and nice nearly new penknife.’ Harry Kinley gave up his cabin to a dozen children and their Sunday school teacher. One mother gave her front door key to the chief officer, asking him to lock her front door if the ship went back to Guernsey because she had forgotten to do so. The captain of the SS Haslemere stated:

On arrival in Guernsey I was informed that I was required to leave as soon as possible with 350 children who had been on the quay since 0300 hours.

Numerous vessels, including ferry boats, mail boats, cattle boats and cargo boats evacuated children and adults to England. The SS Whistable picked up children from Jersey then proceeeded to Guernsey, where the captain noted:

Alarm at Guernsey appeared rather acute, and people were presenting themselves faster than they could be embarked. There were large numbers of cars left abandoned on the quay … we took on 340 people, 150 children and around the same number of women. The officers’ quarters were reserved for the aged and infirm, invalids and nursing mothers.

Sir Geoffrey Rowland stated that as the evacuees left Guernsey, ‘they were leaving, just hoping for the best, in a true British way.’ As one ship parted from the quay, the national anthem was sung as the gap quickly widened between those on the shore. John Warren wrote to a relative in England to describe the events taking place in Guernsey:

The startling developments in the war situation are having a rather alarming effect on the islands. We are so close to France that no one can tell what may happen from one day to another. The authorities have ordered the evacuation of schoolchildren, and parents with young children are also being advised to leave as soon as possible … the islands are being demilitarised to prevent air attacks. I can tell you it has been an extraordinary experience as it has all happened so suddenly. Lots of people are leaving and the island already seems half empty!

Mrs Trotter noted that:

Banks still had their long queues, and one heard on every side the question – are you going? Some shop girls panicked and [went] off onto the boats with just their handbags and very little else. A baker’s van man got the wind up, drove his van to the quay and walked on board, leaving the van with its load of bread to be removed by anyone who wished.

On 20 June, in an attempt to calm things down, the evacuation announcement was reissued in the Star, with the added comment that evacuation ‘was not compulsory, but voluntary’, and adding ‘No cause for panic, Run on Banks must stop. Advice to carry on as usual’. The Star also produced posters bearing statements such as ‘The Rumour that General Evacuation has been ordered is a Lie’. However, someone else produced posters with slogans such as, ‘Keep your Heads. Don’t Be Yellow. Business as Usual’, but these seem to have added to the confusion. They also appear to have caused friction between some who were leaving and some who were staying. Winifred Best recalled:

I left with my mum and dad. We got to the harbour and lots of people were upset that there were posters up saying ‘Don’t be yellow, stay at home’.

Ted Hockey, the harbour signaller, heard officials persuading evacuees not to leave:

They said that trade would carry on as usual, there would be no worry or trouble, and if it came to the worst, they would see that everybody got safely away. They had cars going round with posters, saying ‘don’t be yellow’. As a result of this, I saw one ship which could have carried 4,000 people and I doubt she carried more than 50!

As Mr Symons prepared to leave, he heard an official saying, ‘Look at the rats leaving the sinking ship!’ Yvonne Russell’s mother and siblings had already left Guernsey so she ‘decided to follow them to England, and to leave with my father, however, some people had decided to stay, and were calling those who wanted to go “cowards”.’

Merle Roberts was a student teacher at Capelles Junior School, and wrote:

The harbour was thronged with agitated people trying to decide what to do. The noise was terrific, with broadcasts telling people ‘not to be yellow and not leave the island’. Some decided to go back home and take the consequences, others to stick to their decision to go.

Martin Le Page recalled:

This was not the time for me to be faced with yellow posters, with black lettering which read ‘Don’t be yellow, stay at home’ … how I longed to give the idiot who thought that one up a piece of my mind.

Some Guernsey and Jersey newspaper reports criticised the adult evacuees and said, ‘If the people are going to be true to their traditions, they should go back to their homes so that they can follow their ordinary occupations.’ Another referred to ‘people scuttling away in an attempt to save their own skins.’ One child heard adults talking about who was leaving:

‘Yellow’ poster.

They would say ‘so and so is leaving, they’re yellow.’ And I remember seeing Mr So and So a few days later and I looked at him and he wasn’t yellow, he was a perfectly normal colour.

The evacuation of the schools gave thousands of young children the opportunity to escape, but interviews show that many older children remained on the island with their fathers, to look after the family home and business. Harold Le Page recalled:

My mum and sister left Guernsey on 22 June, but Dad wanted me to stay with him, I was nearly thirteen and he needed me there to help with the farm – his brother who helped him previously on the farm had gone to join the Army.

Only men of military age were permitted to leave on the first wave of official evacuation ships, although some men, and a number of complete families, managed to leave the island on other vessels. A number of Guernsey men and women who had been born in England left the island because they feared ill treatment from German forces if the occupation did take place.

Mothers and single women had to decide whether to offer to accompany the schools as helpers, or to remain behind. Mrs Ruth Alexandre wrote in her diary, ‘News of demilitarisation of the island – we registered, chaos and confusion reigned, didn’t know what to do, but was advised to go.’ About 500 women left in this way, and their stories are particularly emotional. Reta Batiste left as a helper with the Forest School, and in her diary she described leaving her husband:

Wilf took our suitcases down to the Gouffre for us, his last words were ‘I cannot bear to see you off’, it was too much for him to bear, then we each went our way. It was a dreadful feeling, the whole party in the bus, waving, crying goodbye. The children were singing away not realising what it all meant.

Lorraine and Stephen Johns left with their four-month-old baby Elizabeth, and Violet Hatton left with her son Brian, aged six months. After her daughter had evacuated with her school, Olive Le Conte left with her baby, and wrote in her diary:

Margaret left at 3 a.m., I left with David in his Kari cot at 10.30 a.m. Osmond took me to the boat. Left my home clean and tidy, did not put anything away. Leaving my darling husband and home was terrible, am feeling broken hearted.

Lorraine and Stephen Johns with Elizabeth.