Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: 404 Ink

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Inklings

- Sprache: Englisch

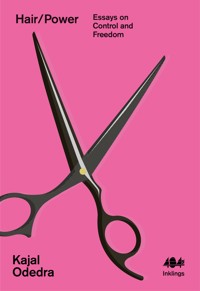

Hair is potent. Its presence and its absence has profound influence upon our lives, across race, gender, sexuality, status, and more. It will grow in places you don't like and it may desert you – suddenly, or gradually. Whatever your experience, you have had a relationship with hair and its power. Kajal Odedra considers how hair has shaped society today, from the 'perfect' blondes in the school playground to the angry skinheads on the streets. Mohawks, wigs, afros, these are just a few of the ways in which hair has been part of history and wider activism. The word 'essay' derives from the French 'essayer', meaning 'to try' or 'to attempt'. This is Odedra's 'try' at hair – part memoir, part observation across history, politics, religion, and culture. Hair/Power explores the power, control and ultimate liberation that hair can provide.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 103

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Hair/Power

Published by 404 Ink Limited

www.404Ink.com

@404Ink

All rights reserved © Kajal Odedra, 2023.

The right of Kajal Odedra to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining the written permission of the rights owner, except for the use of brief quotations in reviews.

Please note: Some references include URLs which may change or be unavailable after publication of this book. All references within endnotes were accessible and accurate as of February 2023 but may experience link rot from there on in.

Editing & typesetting: Laura Jones

Cover design: Luke Bird

Co-founders and publishers of 404 Ink:

Heather McDaid & Laura Jones

Print ISBN: 978-1-912489-70-1

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-912489-71-8

Hair/Power

Essays on Control and Freedom

Kajal Odedra

Contents

Prologue

Introduction

Chapter 1: Blondes/Conformity

Chapter 2: Buzz Cuts/Anger

Chapter 3: Mohawks/Rebellion

Chapter 4: Salons/Community

Chapter 5: Wigs/Play

Conclusion

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Inklings series

For the Odedra girls

Prologue

When I started to think about hair and its power, I didn’t know where to start. It is a messy, tangled subject. It is vast yet so personal. It is dominating yet we don’t quite realise the impact it has. While ruminating over this, I read Susan Sontag’s 1979 diaries where she reflects on the allure of lists.

‘I perceive value, I confer value, I create value, I even create – or guarantee – existence. Hence, my compulsion to make “lists.” The things (Beethoven’s music, movies, business firms) won’t exist unless I signify my interest in them by at least noting down their names.’1

A decade later, in the same diaries, she writes a list of all her likes (fires, Venice, tequila, sunsets, babies, silent films) and dislikes (washing her hair (or having it washed)).

Sontag railed against the standards placed on women and wrote extensively about beauty, sexuality and power. It seems comforting to me, when in the face of messy, complicated matters so entwined in every inch of our lives, to create some order with a list. Her lists were a way of examining, a place to begin. Perhaps to see something objectively, we need to start by listing all of the things, like they are objects?

So, in a nod to Sontag, here is a list of my dislikes and likes about hair:

Things I dislike

My moustache,

The hair on the sides of my face (though sometimes I am endeared by it),

The maintenance of being a woman with a lot of hair,

Cutting myself when I shave,

Malting in every house I live or rest in,

Razors,

Bleach,

My hairy fingers,

In-grown hairs,

Hair found in food,

Hair found in my mouth.

Things I like

The colour of my hair that fools people into thinking it’s black when it’s really dark brown,

The smell of myself when I have hairy armpits and don’t wear deodorant,

The feeling of shaving months old hair from my legs,

Using a strand of hair as substitute for floss,

How free I feel when I don’t shave at all,

Tweezing (any part of my body),

Playing with other people’s hair,

My hairy arms,

Unearthing an ingrown hair,

Having my hair pulled and played,

Washing my hair (or having it washed).

Introduction

When my mum first allowed me to bleach my moustache I was convinced my life was about to change. I was fourteen and had waited a long time for this moment, of removing the obstacle I saw in my path to being accepted. I imagined the boy in my class who I had a crush on asking me out. I imagined the pretty girls finally wanting to be my friend, the girls without black whiskers growing on their upper lips. My life was about to really begin.

The bleach I had waited for all this time came in a turquoise and white tub, it was called Jolen. Just like the one I had seen my sister use over the years but Mum had refused to let me until I was ‘old enough’.

I opened the tub of thick white cream, dense and heavy, smelling of dangerous chemicals, reassuring its ability to solve my problems. It came with a tube of powder that I carefully measured out into a saucer with the accompanying plastic measuring spoon. I added dollops of the thick cream and mixed until it was a paste that held so much hope. My sister did this very ritual every few weeks like a student preparing for an exam. I applied it thickly, covering every sprinkling of hair above my top lip. It stung almost immediately. But that’s a good sign, I thought, it must be working. Sat on the edge of my bed, eyes glued to the clock for ten minutes before scrambling into the bathroom. Still reading the instructions to make sure I completed every step to the letter, I carefully wiped away the cream using wet toilet paper. I could feel a burn with every touch and washed my upper lip in cold water to cool it down. I dabbed it dry, careful not to aggravate my now very pink and tender skin. I looked in the mirror, expecting, hoping, it had vanished. But I could still see it. Clearly. Except now my moustache was a yellow that didn’t quite blend in with my brown skin. Worse, it seemed to glow, drawing more attention to itself. Maybe it will get better when the area is less red. It didn’t. School the next day was excruciating. I felt humiliated as I pretended not to hear the sniggers and, at times, blatant laughter in my face. After a few tries in later months, I got the hang of bleaching to the correct shade. And a few years later I was allowed to graduate to hair removal cream.

I’ve been a bit obsessed with hair all my life. Partly because I am a hairy person, more so than your average white girl at least, but I’m probably averagely hairy for an Indian. When I was young, that didn’t matter because the world I existed in for most of my childhood was white. The books were white, the people on TV were white, and the kids at school, so white. I wanted to be like them all. For a long time I went to great lengths to contort myself as much as I could. I shaved everything including my arms because they were abhorrently hairy to me. I dyed my hair blonde. I over-tweezed my already thin eyebrows. I tried to hide my Indian identity. I felt ashamed when people asked me about it. I felt I was a lower class just from my brown skin and Indian heritage. Rather than feeling proud of the hard work, long hours and many obstacles my parents had to overcome to get me to the white school, the white university, I felt I should to hide it, so that people might assume I was like them. I was so dissociated from myself it was like acting in a play but without a script, winging it, hoping nobody noticed I wasn’t supposed to be there.

It wasn’t until my mid-twenties, while I worked as an activist, that I realised how much hate I’d internalised. Campaigning with young people and refugees became my day job while I volunteered in the evenings and weekends. I became conscious of the power dynamics I existed in, not just politically but also the way I perceived my own body, the way I existed in spaces. That power dynamics were playing out everywhere.

Michel Foucault, mid-20th century French philosopher, said there is no knowledge that isn’t influenced by power. That power is constituted through accepted forms of knowledge, scientific understanding and our ideas of ‘truth’. Politics and ‘regimes of truth’ are the result of scientific discourse and institutions, and are reinforced (and redefined) constantly through the education system, the media, and the flux of political and economic ideologies. In this sense, the ‘battle for truth’ is not for some absolute truth that can be discovered and accepted, but is a battle about ‘the rules according to which the true and false are separated and specific effects of power are attached to the true.’1 Science, history, art, nothing is objectively true, the knowledge we consume is power at play.

Everything I learned and understood about myself was subjective to the space and time I occupied. There was no objective truth about my appearance and whether I belonged. Disillusioned, I was frustrated with having soaked up all that nonsense for so long. For only starting to question it in my adulthood.

I embraced myself, stopped shaving my arms. I don’t know how but when the hair grew back I no longer felt ashamed. Returning home from London for weekends I learned about my heritage and was so curious. I would ask my parents questions about when they first arrived to the UK, what was it like for them? What did they struggle with? I wanted to know my mum’s recipes – I would stand by the hob while she poured spices into her creations, irritating her by asking for specific measurements. Just a bit, whatever you think. We don’t measure!

Foucault believed that our ways of thinking were limited by the knowledge of the day, and that stopped us from growing. I wanted to write the essays in Hair/Power to analyse how the knowledge and perceptions we have about hair is shackling our freedom. This book is not a history of hair, nor is it a thesis – I’m not going to tell you what to think or what to do after reading.

The word ‘essay’ derives from the French ‘essayer’, meaning ‘to try’ or ‘to attempt’. Michel de Montaigne was the first author to describe his work as essays, in the 16th century, to say that he was attempting to put his thoughts into writing.2 In the coming pages I offer such essays that explore how hair has impacted me, as well as other identities and cultures, but I can’t claim to be speaking from any experience and lens other than my own.

So this is a ‘try’ at hair; a contemplation, an enquiry, an excavation. It is a conversation with Foucault and Sontag and my childhood. A complicated love letter. Hair, that is so wrapped up in my sense of self and intrinsic to my path into activism. This is a try at what hair means to me.

Chapter 1: Blondes/Conformity

Stacey’s hair was golden. She had a fringe that would flirt with the lashes of her eyes. When she looked up it was like she was peering through a curtain. In all the books in our primary school library, the characters looked like Stacey. Perfectly blonde, perfectly blue-eyed. They were often very kind and ingratiating. The perfect little girls. Stacey wasn’t always kind. In fact, she could be quite cruel, in the way girls learn to be on the playground. The other girls didn’t compare to Stacey, but they were in her chorus. Each week she would pick her favourite, the chosen girl who would be allowed to bathe in Stacey’s limelight, have the privilege of walking hand in hand, promenading the concrete playground. She would sit with Stacey at registration and sometimes be invited to her home for fish fingers, if she was lucky.

I was not like Stacey. In fact, I could be deemed her exact opposite. My hair was so dark that the other kids would say it’s black. It’s dark brown, look! I’d protest while placing the strands against a black surface to expose its lighter colour, because I didn’t want to be associated with the word ‘Black’. It was incongruous to the world I lived in then. My world before was a safe bubble in Leicester, where the kids looked like me and talked like my family, with dark skin and thick accents from different parts of the world. Now I was in Newhall, an ex-mining village in Derbyshire, and I didn’t look, or sound, like anyone around there. Everything was white.