2,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Do you love your natural hair?

Some of the world’s most inspiring black women tell us about their attitudes to, and struggles with, their crowning glory. Kinky, wavy, straight or curly, this book will help you celebrate your natural beauty, however you choose to style your hair.

With an overview of the politics and history of black hair, the book explores how black hairstyles have played a part in the fight for social justice and the promotion of black culture while inspiring us to challenge outdated notions of beauty, gender and sexuality for young women and girls everywhere.

The power is in our hair. And we’ve come to tell the world what ours can do!

Also includes thirty interviews with women of colour about their hair and beauty journey including Jamelia, Angie LeMar, Dawn Butler MP, Stella Dadzie, Judith Jacobs, Carryl Thomas, Anita Okunde, Kadija Sesay, Anastasia Chikezie, and Chi Onwurah MP.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 425

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Saskia Calliste

Saskia is assistant editor for Voice Mag UK where she writes about societal issues and reviews fringe theatre, including Edinburgh Fringe in 2019. She freelanced for The Bookseller and has had her work published in the 30th-anniversary edition of The Women Writers’ Handbook (Aurora Metro). She is the author of the blog sincerelysaskia.com, has an MA in Publishing and a BA in Creative Writing & Journalism.

Zainab Raghdo

Zainab is a writing assistant and content creator at ContentBud, and the author of the thecoffeebrk.com. She has an MA in Publishing and a BA in English Literature and Classical Civilisation and has freelanced for many years, recently being published in a the new arts journal, The Bower Monologues, and the online African Woman’s magazine AMAKA.com.

First published in the UK in 2021 by SUPERNOVA BOOKS

67 Grove Avenue, Twickenham, TW1 4HX

Supernova Books is an imprint of Aurora Metro Publications Ltd.

www.aurorametro.com @aurorametro FB/AuroraMetroBooks

Instagram @aurora_metro

Foreword by Stella Dadzie copyright © 2021 Stella Dadzie

Authors’ Note by Saskia Calliste & Zainab Raghdo copyright © 2021 Saskia Calliste & Zainab Raghdo

Our History by Zainab Raghdo copyright © 2021 Zainab Raghdo

Her Hair Stories compiled by Cheryl Robson and Saskia Calliste copyright © 2021 Aurora Metro/Supernova Books.

Endnote by Saskia Calliste copyright © 2021 Saskia Calliste

Poems by Kadija Sesay copyright © 2021 Kadija Sesay

Illustrations by Aleea Rae copyright © 2021 @aleearaeart

Editor: Cheryl Robson

Thanks to Christina Webb, Saranki Sriranganathan, Marina Tuffier

All rights are strictly reserved. For rights enquiries contact the publisher: [email protected]

We have made every effort to trace all copyright holders of photographs included in this publication. If you have any information relating to this, please contact: [email protected]

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed in the UK by Short Run Press, Exeter, UK.

ISBNs:

978-1-913641-13-9 (print version)

978-1-913641-14-6 (ebook version)

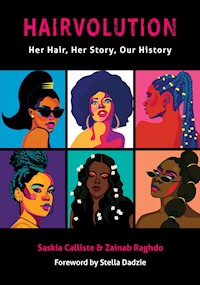

HAIRVOLUTION

Her Hair, Her Story, Our History

by

Saskia Calliste& Zainab Raghdo

with a foreword by Stella Dadzie

poems by Kadija Sesay

illustrations by Aleea Rae

SUPERNOVA BOOKS

FOREWORD

Stella Dadzie

Have you ever had a really bad hair day that felt like it lasted for most of your life? For many Black women, subjected to a constant barrage of European beauty norms and ideals, this is our reality. At least, it used to be. In recent years, we have witnessed a ‘hairvolution’ – a quiet revolution in how we see and style our hair – and the trend is increasingly Afrocentric. From complex braids and cornrows to sculptured cuts, dreadlocks, fades and symmetrical Afros, Black women are no longer prepared to deny our hair its natural birthright.

For many of us, the journey to self-love and self-acceptance has been slow and painful. As a people, we have had to contend with centuries of undermining messages, denying us our humanity and mocking every aspect of our appearance – our noses, our lips, our buttocks, our skin and (inevitably) our hair. So different in texture to that of our European detractors, it was an easy target. Untamed hair and savagery were seen as symbiotic. If our tresses weren’t combed, curled and compliant, somehow this was seen as evidence of a wild, wanton character, divinely ordained and innately inferior. Viewed through the colonizers’ gaze, we were uncivilized, primitive, sub-human beings with the hair to match.

As those of us scattered across the diaspora would soon discover, the word ‘beauty’ was only ever associated with fair skin and sleek, Europeanized hair. Despite a widespread belief that Black women had lured the hapless white man into a state of lost innocence, officially we were described as the living embodiment of everything Europeans deemed ugly. In a world where a person’s race determined their social mobility, many of us did everything possible to disguise our African roots. The kink in our hair, so hard to disguise, was viewed as a mark of shame.

Generations later, we are still grappling with the psychological damage this prolonged assault on our self-esteem has caused us. We are reminded of this fact every time a little Black girl begs to have her beautiful curls straightened because all her schoolmates are white and she longs to look like them. It’s not just our children who suffer. You only have to step into a Black hair salon to see the hoops some of us are prepared to jump through in pursuit of this spurious ideal. Harsh chemicals, red-hot tongs, weaves, relaxers, extensions, the list is endless. Shops that sell Black hair products display row upon row of tubs and bottles, all of them promising to tame our unruly locks, many of them eye-wateringly expensive or overtly colourist. It’s true, more and more of us are learning the value of natural products – shea butter, coconut oil, products our ancestors used that are tried and tested – but we still have a way to go. By demystifying the experience and shedding light on its long, complex history, books like this will assist us on our continuing hair journey.

Hairvolution takes us back to a time when African women wore their hair proudly, with no fear of ridicule or judgement. It shows how the process of enslavement and mental colonization robbed us of that pride and left us shackled to our own self-hatred. The interviews – my own included – reveal the traumas, influences and moments of revelation that have defined our relationship with our hair. They speak honestly and intimately to an experience many of us will have shared.

For the first time in decades, Black women are reclaiming their bodies. We are strutting our stuff, revelling in our rich diversity. For my generation, the moment of reckoning was symbolized by the Afro – Angela Davis’s magnificent halo, so symbolic of Civil Rights and the message of Black self-love and self-reliance. For the Black Lives Matter generation, the icons will be different – the sight of Meghan Markle’s mum wearing her locs at the royal wedding, perhaps; or an image of Erikah Badu’s wonderfully creative mane spilling from its regal headwrap. Every Black woman who bucks the trend and wears her natural hair with pride is a potential role model, empowering future generations to love and respect their hair.

Of course, whether teachers and employers will see these changes in the same light remains to be seen. We still hear tales of Black children suspended from school because their hairstyle did not ‘comply’. Turn up to an interview with your hair in locs, and your chances of getting the job may well have been blown before you even opened your mouth. But attitudes are slowly beginning to move with the times. Perhaps, in the not too distant future, even white folks will recognize that there is room in this world for many different hairstyles, some of which don’t aspire to imitate theirs. It’s a Hairvolution that is long overdue.

’AIR

Fe-e-e-el this!

Go on!

Fe-e-e-el it!

Soft ’n’ wiry all at the same time –

’ow do you people ge’ your ’air like tha’?

You people?

Yeah – you culud people.

’Ow am I gonna ge’ a brush frew tha’? Tuf ’ innit?

Bounces back – all springy.

Listen, wha’ I’ll do for you, love, is,

after I wash i’, if it gets any tuffa,

I’ll ge’ some scissors,

cu’ it all orf – might grow back straight

‘n’ nice’n’ long –

then I can brush i’ like me gels ’air.

No extra – a-a-a.

Alrigh’?

Gawd Blimey!

Fe-e-e-el this!

– Kadija Sesay

Contents

Foreword by Stella Dadzie

Our History by Zainab Raghdo

Authors’ Note by Saskia Calliste & Zainab Raghdo

Poems by Kadija Sesay

Her Hair Stories (Interviews):

Annika Allen

Eva Anek

Anita Asante

Caroline Blackburn

Doreene Blackstock

Dawn Butler

Anastasia Chikezie

Stella Dadzie

Sokari Douglas Camp

Stephanie Douglas Oly

Deitra Farr

Rachel Fleming-Campbell

Ruthie Foster

Jamelia

Judith Jacob

Bakita Kasadha

Angie Le Mar

Francine Mukwaya

Jessica Okoro

Anita Okunde

Stella Oni

Chi Onwurah

Olusola Oyeleye

Shade Pratt

Rianna Raymond-Williams

Djamila Ribeiro

Vivienne Rochester

Kadija George Sesay

Cleo Sylvestre

Carryl Thomas

Jael Umerah-Makelemi

Endnote by Saskia Calliste

Index

OUR HISTORY

This book is a celebration of our history and culture as Black women. It seeks to affirm the beauty of Black women and, in particular, our natural kinky hair. Western beauty ideals often run counter to African beauty ideals. Where the West has idolized, in women especially, fairer skin and long, smooth, straight or wavy hair, African beauty ideals have traditionally leaned more towards darker skin and kinkier hair that can be fashioned into elaborate communicative styles. Most African hair grows upwards, rather than downwards; it is not “smooth” and “flat”; rather, it coils and springs, and is often braided, twisted, or covered up and adorned with beads, ribbons or ornate fabrics.

Today, especially in our cities, diversity is being recognized as one of the strengths of modern society. Our differences are something to be celebrated, whereas the imposition of one notion of cultural difference over another as being either “superior” or “right” is what has caused the great racial divide that we have seen unravelling before us in the last few years. As a result, Black women living in the West have been judged and assessed against unattainable white beauty ideals for centuries. In the last few years, this way of assessing and valuing women’s appearances has created a far-reaching dialogue about our globalized racialized history in an attempt to undo its social consequences.

Although this book has been written in the UK, it aims to cover Black hair and what hair means for Black women internationally; therefore, it is necessary to look at Black hair and hair identity through the lens of African American slavery politics to understand how persisting beliefs and values were formed.

Cultural Identity

Slavery is at the core of every law and social construction that affects the African diaspora.

Its legacy is still with us today due to the sheer scale of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade in which 12.5 million Africans were transported to the New World with only 10.7 million surviving the terrible journey known as the Middle Passage. The number of Africans exported to the United States as slaves during the four centuries in which the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade flourished is estimated to be around 400,000, while the vast majority of enslaved African were transported to work on the sugar and coffee plantations in the Caribbean islands and South America, with over five million being transported to Brazil mainly by the Portuguese traders.

While much has been written about the treatment of slaves in the diverse colonies to which they were transported, American culture has played a significant part in global consciousness through the influence of Hollywood, American movies and the media. Through this cultural influence, it has affected global reactions to, interactions with and behaviours towards Black people everywhere, but especially in anglophone nations like the UK.

Hair Matters

Hair has traditionally been one of the key ways in which a group of people express themselves. Whether that was to have the hair covered up, worn high, worn in braids around the head or cropped short, hair has never simply been an adornment but has always been influenced by the prevailing cultural and religious attitudes of the time. Hair has changed with the times and the fashions to correspond with developing ideas of beauty, gender identity, morality and medicine, in every culture.

This historical backdrop to the perception of hair in Western European culture shaped ideas about African hair that were to follow. Femininity and individual beauty standards are the first steps to understanding the significance of hair in Africa prior to the arrival of the colonizers from Western Europe and the harmful effect that they had on the continent. Emma Dabiri in her 2019 book Don’t Touch my Hair explains that in Western African cultures, it was believed that a person’s spirit nestled in the hair, as it was the most elevated point on a person’s body and therefore closest to the divine. If anyone got a hold of your hair, it was thought – as is still believed by many of African descent today – that they could cause you serious harm. That they could “juju” you, or perform Obeah, cast spells or ensnare your spirit, through the traces of it which remained in the hair, even if it is just a single strand.

This notion of divine hair is a continuous thread that runs throughout pre-colonized African spirituality. One of the most venerated gods in the West African pantheons is Oshun (or Ochún, Oxúm), one of the goddesses of the Yoruba, an ethnic group from West Africa whose descendants in the diaspora can be found in high concentrations in Europe, America and South America. Oshun functions as the mother goddess of the Yoruba pantheon, a primordial deity, one of the manifestations of the Yoruba supreme being and the most important river goddess of the Orisha. She is the goddess of birth, fertility and, most significantly, hair. One of the many symbols of Oshun is the wide-toothed comb or pick, familiar to many of us who have had to use it to get the knots out of our hair, and familiar to our ancestors as a sacred tool through which the goddess Oshun communicated with mortals.

The spiritual significance of hair in pre-colonized West Africa is in no way being exaggerated. Pagan deities and pantheonic deities tell us what is, or was, most important to the people, cultures and societies who worshipped them at any given time. Just as societies such as the ancient Greeks had gods and goddesses associated with the hearth or virginity because these notions were important to their way of life, so too the Yoruba had a goddess of hair, because that is what was most important to them.

Whilst there are few verified images of Oshun left, surviving sculptures and carvings of other African deities as well as wall paintings of Ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses show us that images of the deities almost always coincided with the beauty standards of the cultures and people whom they served. So African deities, like Oshun, looked African, with various types of African hair, body shapes and facial features –- and they were considered beautiful because of that. By extension, her worshippers were also deemed to have beautiful, sacred hair and treated it as such.

Oshun wood carving, Museum Afro-Brazilian, Photo: Jurema Oliveira

In their pivotal book Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America Ayana D. Byrd and Lori L. Tharps note that, “West African communities admire[d] a fine head of long thick hair on a woman.” This “fine head of long hair” was indicative of a “life-force, the multiplying power of profusion”. That profusion often translated itself as fertility and showed a woman to be bountiful in her ability to bring forth and raise children. It also suggested that the woman was capable of utilizing the fertility of the earth and the sky, like the goddess, to cultivate the land and bring forth a good harvest to support the lives and livelihoods of those around her.

Hair did more than communicate beauty and fertility. It acted as a means of communicating all sorts of messages, both negative, positive and social. It functioned as an “integral part of a complex language system” that helped to structure societies and helped their members to interact with each other without words. But if hair could be a signifier of health and fecundity, it could also be a signifier of ill-health. In Yoruba cultures, if a woman left her hair undone, it was a sign that something was wrong, either that she was bereaved or emotionally unstable. Byrd and Tharps tell us that the Mende tribe of Sierra Leone viewed unkempt, neglected hair as representative of loose morals or insanity; not so different from many of our own reactions today when we see outrageously unkempt hair.

Ethnographer Sylvia Boon noted that the Mende people had a special word for a serious state of unkempt hair, “yivi”, showing us just how significant it was for these cultures to be able to determine, immediately, someone’s position in society or psychological state from the appearance of their hair.

Hair also functioned as a means of indicating a person’s social status within the community: their profession, hierarchy and family name. Byrd and Tharps suggest that a person’s surname could be guessed from their hairstyle and that people from the Wolof, Mende, Mandingo, Yoruba, Fulani, Ashanti, Himba and Igbo all had different hairstyles specific to their tribe alone. In Senegal, girls who were not yet of marrying age, or who had not hit puberty, had their head partially shaved to show this. A bereaved woman had to deliberately leave her hair unattended for the specified mourning period. In Yoruba culture, women in polygamous marriages traditionally wore their hair in a “kohinsorogun” style to show their sister-wife status.

As hair was so vital to the continued prosperity of African communities, the person charged with tending to the hair – the hairdresser – “always held a special place in community life”. According to Byrd and Tharps, the hairdresser acted, in part, like a guide, a spiritual medium, and anyone who could master the art of hair and braiding would “assume responsibility for the entire community”.

Hairstyling was such a sacred task that, at times, only a family member could be trusted to do it, or you would be assigned a hairdresser from birth to do your hair for the rest of your life. Hairdressing and “hair braiding sessions were a time of shared confidences and laughter; the circle of women who do each other’s hair are friends bound together in fellowship”. The hair grooming process included, as it still does for many of us, washing, combing, braiding, oiling, twisting and/or decorating the hair with ornaments, including “cloth, beads and shells” and the time spent doing this was considered sacred.

While many African cultures revolved around hair in one respect or another, a large part of that worship, and appreciation, came from the lack of the concept of race. It is always easier to find beauty – or to understand your own beauty to be acceptable – when it’s all you know. And for those Africans who had not travelled nor traded with Europeans, there was no concept of a white European race. There was also no concept of a Black race either. In Africa, being Black was the norm, and so was African beauty, including African hair.

The Impact of Colonialism

When Europeans arrived on the African continent in search of trade, they began “Othering” the Africans and recording this process in their letters and writings which were published in books. This meant that their ideas not only survived but were widely distributed. Through this the concept of race was created and the differences between the Europeans and the newly classified Black African race were preserved.

With this new classification came ideas about which race was civilized and which was not. The colonizers sought to justify their exploitation of their fellow human beings by claiming that their set of beliefs and values proved their superiority. They then used their power and influence to impose these ideas on the peoples who were colonized, leading to a loss of appreciation of local cultural traditions by those who were dispossessed. But though race and racial disparity began with the arrival of Europeans, racial hatred did not. The Europeans’ initial reaction to Africa and African customs was, for the most part, a response of awe.

Drawing by JB Debret of enslaved Brazilian women, 1834 Image: NYPL Digital Collections

We know that Europe had a long-standing trading and cultural relationship with North Africans – the Moors – who at the time were considered to be of African origin rather than Arab. These two groups managed to do business fairly amicably for centuries.

In episode one of the BBC documentary Black and British: A Forgotten History, British art historian Janina Ramirez and historian David Olusoga refer to Balthazar, one of the three kings said to have attended the birth of Jesus who brought the gift of Frankincense and Myrrh (which were traditionally extracted from Northeast Africa or the Horn of Africa), as being a Black man. The documentary shows viewers a carved, wooden altar piece circa 1530s in Hereford Cathedral, West Midlands, which again depicts one of the three kings as clearly being an African.

His blue robe is adorned with gold. His gold crown is brighter than the crown of the two other paler kings who flank him, and it shines more brightly than any other material in the sculpture. Ramirez explains that his gift in the shape of a “cornucopia, a horn of plenty,” reveals how the medieval European mind saw Africa: as rich, plentiful and beautiful. The figure’s position in the image, at the centre with all other activity radiating out from him, suggests that not only was all beauty and bounty extending out of Africa and the African, but to an extent, so did all humanity and Christian religious dignity. Given the subject of the painting, it is unlikely that the artist or the commissioner would have featured such a pivotal character if the African race was thought to be inferior to others at the time.

In The Alhambra (a Moorish palace) by Rudolf Ernst. Photo HistoryNmoor

In the 16th century, as European discovery and colonization of the New World expanded to the North Americas, South Americas and the Caribbean, the Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, British and French colonialists found themselves in the “unprofitable position of occupying entire islands” with no experience of how to work them.

Having tried to enslave the indigenous people of the New World without much success, the colonizers were discouraged from this by the release of a papal bull – Sublimis Deus – by Pope Paul III in 1537 which prohibited the enslavement of Native Americans. As a result, “realizing the need for an imported labour force, the Europeans reassessed their West African trading partners.” To sanction the human trafficking of Africans, some of the European traders revisited a previously passed bull by Pope Nicholas V, namely Dum Diversas which, in 1452, sanctioned the move to “reduce their persons [Saracens and pagans] into perpetual servitude.”

This bull gave Catholic Europeans justification from the highest level to make trading arrangements with partners in Africa to capture Africans, who were considered pagans, and commit them to a life of permanent enslavement until, as the name of the bull dictates in Latin, “they are different”, a practice which the Protestant traders soon followed.

This idea of “difference” was interpreted to mean that even religious conversion would not absolve the African of the sin of their racial difference. By constructing the concepts of “white”, as the purer race versus the Black, impure race, Europeans pitted the two against each other.

Professor John G. Turner in the chapter entitled “The Great White God” from his book The Mormon Jesus: A Biography, explains that “a skin of darkness” became a mark of “sin”. This deliberately stark language worked within the existing framework of print and literacy in Europe to create the enduring image of the savage, sub-human Black man set against the portrayal of the more enlightened, advanced white man.

Religion and Science Converge

The emphasis on biological differences was taken further by many Christian theorists. According to Craig R. Prentiss in his article “Coloring Jesus: Racial Calculus and the Search for Identity in Twentieth-century America” (2008), European Christians understood “Black” people as pre-adamites, a race of men, or beasts, created before Adam, the true “man”. And if man is created in God’s image, and the European man is the “real” man, then it follows that the only human that God could possibly accept would be a European, often in English-speaking form. Even the depiction of Jesus was adapted to conform to this notion and, as we know from much of the discussion surrounding the idea of “white Jesus” today, the image of Jesus in churches throughout the world is almost ubiquitously that of a white man rather than a man of Middle Eastern origin. The emphasis on biology and the idea that godliness and purity can only come from “biological lineage” means that those who do not have the right lineage, and who will never be able to attain the correct lineage, would always be sinners; they would always be ungodly, and so, whether they converted or were baptised, they would always be “reduce[d] [to] (…) perpetual servitude” .

John G. Turner points out that “the belief that dark skin reflects God’s curse was deep-rooted in Western Christianity”. The belief was that the sin of Cain, his subsequent banishment and the mark he was cursed with – believed to be the mark of Black skin – was passed on to his ancestors. This was a popular way of explaining the inherent subservient status of the Black race.

What’s more, by the 1800s, when the benefits of the slave trade were globally acknowledged and the trade was fully established and endorsed, the ideas put forward by Charles Darwin in his books The Origins of the Species and The Descent of Man inadvertently helped to support the biblical argument for white superiority, whether he intended to do so or not.

Young “Hottentot” image courtesy of New York Public Library

Darwin suggested that nature and evolution are based on the “survival of the fittest”. And he posited that part of this survival was having lighter skin which made it easier to survive in a stronger, more civilized world ― a world constructed by Europeans.

In The Descent of Man, Darwin also refers to South Africans, by use of the derogatory term “Hottentot”, as “savages” whom he describes as being far closer to our alleged primate ancestors, the apes, than civilized Europeans. He theorized that these savages were examples of the “primaeval man”, the missing link, only one step down from the apes, a beast in the evolutionary chain.

What is even more problematic is that he likens the African to an animal, which could be worked and treated in the same way as livestock. All of these negative beliefs and attitudes towards African peoples combined to support the notion of white superiority. This is why white normative beauty standards came into being and why Europeans have been reluctant to deviate from them, long after the justifications for white supremacy fell out of fashion.

Loss of Identity

Edith Snook in her article “Beautiful Hair, Health, and Privilege in Early Modern England” records that European hair received the epithets “Beautiful”, “finely textured”, “supple”, “pliable”, with “delicacy” and female characters in prominent European literature, who have the highest moral standing or beauty, are usually described as having fair or golden hair which reflects that disposition.

In literature, these idealized, beautiful, virtuous, elite women – the women with reserves of social capital who are at the centre of romances and love poetry, and are praised for their appearance – have hair notable for its abundance, movement, and slight, natural curl or wave. In all of these works, waving, abundant hair that moves belongs to idealized characters, those possessing virtue, purity, elite status, and bravery – the woman who is an aristocrat, praised for her beauty. Hair has signifying power. It provides rhetorical reinforcement for identities venerated as socially advantaged, with purportedly attractive hair used to insist that its possessor is socially valuable.

These ideas about hair – what beautiful hair looks like and why the possession of it is so vital – created the white normative beauty standards that Africans could never hope to achieve. In contrast, Afro-textured hair was regularly referred to as “wool or fur”, animalistic epithets negating the humanity and morality of the African as prescribed by the religious and scientific theories noted above.

Simonetta Vespuscci by Botticelli, Gemäldegalerie Photo: José L. B. Ribeiro

Initially, all of this religious association did little to change the idea of Black beauty in the minds of Black people themselves. The self-deprecation and mental enslavement that would eventually come at the height of slavery did not suddenly take hold just because a person had been captured and put on a ship. To create compliant slaves who would eventually succumb to this way of thinking, Europeans first needed to break Africans. And the best way to break a person is to take away their identity, because separating a person from their home and loved ones alone could not achieve this.

Frank Herrmann, Director of Exhibitions at New York’s Museum of African Art, and a specialist in African hairstyles, notes that “a shaved head can be interpreted as taking away someone’s identity” and “the shaved head was the first step the Europeans took to erase the slave’s culture and alter the relationship between the African and his or her hair”.

By taking away this immense cultural and spiritual aspect of African identity, slave traders asserted their dominance over the Africans and in “arriving without their signature hairstyles, Mandingos, Fulanis, Igbos, and Ashantis entered the New World (…) like anonymous chattel”.

Once enslaved, they endured brutal and inhuman treatment on the plantations. They had a single meal in a day, with “punishments for insolence, slowing down, or rebellion” which “included whippings with a cat-o-nine-tails, sadistic torture, and amputations of digits and limbs”. And given these terrible conditions, it is unsurprising that enslaved Africans had neither the time, resources or the inclination to care for their appearance, least of all their hair and the once “treasured African Combs were [now] nowhere to be found in the new world.” The goddess Oshun had been taken from them – no longer held in high regard if she was remembered at all – and their ancient customs were largely forgotten over time.

Slave women also took to covering up the effects that bad diets and a stressful lifestyle had on their hair. The bald patches and matted tresses were covered with fabric scraps and rags which eventually became “ubiquitous to slave culture”.

Yet, as the Jamaican saying goes, “turn your hand, make fashion.” The enslaved managed to regain the importance of their hair by using the resources at their disposal. Carding combs, which were made for use on sheep fleece, became combs, while the headwrap has been reclaimed and refashioned over the centuries. Many of the headwrap protective styles that we see pop up in the winter today are descended from that tradition of hiding our hair, either when it needs to be protected or when it is undone.

The term ‘Sunday best’ applied to hair as well as clothes. After a week of having their hair bound up, either to stretch it or hide it, Africans often unveiled their hair on Sundays as part of the Sunday best ritual. A New England traveller in Natchez, Mississippi, described Sunday morning rituals in slave quatres as follows: “In every cabin (…) women arrayed in their gay muslins, are arranging that frizzy hair, in which they take no little pride.” Former slave Guz Fester recounts: “In them days all the darky wommens wore their hair in string ’cept when they tended church or a wedding.”

In the absence of traditional African hair care products such as shea butter and coconut oil, the hair was maintained by the use of everyday household products. Tracy Owen Pattons in her essay “Hey Girl, Am I More than My Hair?: African American Women and Their Struggles with Beauty, Body Image, and Hair”, states that enslaved Africans used “bacon grease and butter” to condition and soften the hair, as well as prepare it for straightening and stretching. “Cornmeal and kerosene were used as scalp cleaners, and coffee became a natural dye for women.” All of this shows that despite the atrocious conditions that enslaved Africans faced, one of the few things that kept them going and allowed them to retain their own sense of well-being and self-love was their hair.

Hair Hate

Like the concept of race, hair hate came from the Black slaves’ proximity to the white slave-owning families and estate managers and the comparisons that were drawn between the two. Those working in the houses near the slave masters were required to “present a neat and tidy appearance”. Unlike field slaves who had to make do with simply what they could get a hold of, “house slaves” could go one step further and often took to wearing wigs, ribbons or styling their hair to look like wigs in emulation of their white masters and to distance themselves from the “nappy-headed” ruffians outside.

European hair, like all other things in a white Western normative culture, became the benchmark by which all other hair was judged. And it was often by their hair that a person was judged ― with Afro hair considered as “nappy”, “wooly”, “unruly”, “untidy” and apparently “wild”, the reverse of the straight, smooth, neat hair that was considered desirable. So, the need to assimilate arose.

Hair is crucial to the identification of racial heritage, in many ways, more so than skin colour. Dark skin is not specific to the African race, as Polynesians, Indians and Arabs have also been noted to have dark skin, but they are not racially labelled as Black. However, they have still been Othered; they have been dealt with differently by Europeans. As Dabiri rightfully points out, although a large part of the world population is “melanated”, “there are few populations beyond those of African descent (…) who have Afro hair” and that is what distinguishes Africans from other darker-skinned people and ethnic groups.

Ingrid Bank, a professor of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, compiled the book Hair Matters on the experiences of Black African American women with their hair. In this book, one of her interviewees, Rain, muses that “if she would have had ‘measly, short, nappier’ hair, she would have been less favoured”, supporting the idea that it is hair, more than skin colour, which determines status and racial identity. At the time, status was almost always signified by moral, political and ideological standing, and the more Afrocentric your hair, the more you were assumed to have a low moral, ideological and economic standing.

Inevitably, those who were able to bypass these negative assumptions were Black people with hair closer to the white ideal: Black people with mixed heritage. As a result, the mixed offspring of interracial couplings became the unwitting pawns in this struggle for liberated Black identity. Considered essentially only “half ” cursed, having obtained half of their purity from their white parent, having straighter, less curly hair was held up as the ideal, what Africans were to aspire to ― as close to being white as the African race could possibly get.

The term “house slave” was widely understood to be a (relatively) better position for a slave to have, as opposed to being a field slave, and being a house slave was usually, though not always, associated with being a mixed-raced or light-skinned, looser curled hair Black person. But Byrd and Tharps point out that, before the solidification of the slave laws in the 1640s to 1670s when the slave trade was still in its infancy and less racially defined, “the scant number of white females, [meant that] some European men sought Native American and Black women for companionship, either by consent or by force”. These couplings resulted in children who, because of English Law at the time, were declared to have “inherited the status of their fathers” and could inherit the wealth and land of their slave-owning fathers, and often times owned slaves themselves. Their lighter-skinned and straighter hair spoke volumes of this privilege, or the ability to access this privilege.

By the 1600s, however, the colonies began to reverse this law, and the mixed children of these couplings now inherited the status of their mothers and became “slaves”. In the face of this new adversity, “many light complected slaves tried to pass themselves off as free, hoping their European features would be enough to convince bounty hunters that they belonged to the privileged class”. But lawmakers, aware of these attempts at passing, made it imperative that no trace of Blackness slipped through the cracks, and the one-drop rule came into effect. It ensured that even the blondest, blue-eyed mulatto would still feel the full force of the white legal system. “The rule of thumb for the one drop rule was that if the hair showed just a little bit of kinkiness, a person would be unable to pass as white”. This applied even if a slave had skin as light as many Whites. “Essentially, the hair acted as the true test of Blackness.”

Enslaved house servants with white children. Sketch from The Illustrated London News (1863)

And for Blacks whose hair did not show a “bit of kinkiness”, it meant a life of, if not passing for free, then at least, “less backbreaking labor (…) access to hand-me-down clothes, better food, education and sometimes even the promise of freedom upon the master’s death.” As such, there was a constant battle amongst those who could ‘pass’ to make sure that they maintained and showcased their “good hair”. White people were also aware of the significance of long kink-free hair. It was said that “female slaves with long, loosely curled hair” would often as punishment have their “lustrous mane of hair” shaved off by the “jealous mistress”.

What’s more, runaway slaves were always described as having “bushy hair”. And for advertisements of runaway slaves with loosely curled hair, readers were warned not to be fooled by the “long black curld [sic] hair”, implying that the long head of loose curls generally denoted an innocence and morality of character that this particular runaway slave had forfeited with their rebellion.

And this idea of “good hair”, a term many of us have heard growing-up, began here. “Good hair”, the finer, looser curls, typically associated with, though not exclusive to, mixed Blacks, is ladened with all of the cultural and historical implications that came as a result of this slavery environment. It implies breeding, wealth, freedom, education, good manners, good morals, good lifestyle and all of the relatively enviable trappings of existing in slaveholding countries as someone whose physical appearance bore a closer resemblance to that of the dominant white elite. By contrast “bad hair”, as many of us have been taught throughout our lives, however unwittingly, is “African hair in its purest form”.

In the years leading up to the abolition of slavery, the Free Blacks with extremely light skin and straight hair became known as the “‘mulatto elite” as they still enjoyed a sense of freedom and riches unknown by Blacks with darker skin.

And the maintenance of the physical attributes needed to achieve this status was something that mulattos, quadroons, hexagoons and octoroons fought to preserve well after the abolition of slavery. “They were adept at segregating themselves in tight-knit communities” where they married only other Blacks with similar light colouring and straight hair; they lived in neighbourhoods with people who looked like them and only associated both professionally and socially with people of a similar skin-tone.

Princess Olive of Haiti

Light Privilege

Historical Black colleges, set up for the betterment of the whole Black race (such as Howard University in 1867, Hampton in 1868 and Spellman in 1881), had the unspoken admission requirement of having a “skin tone or hair texture that showcased a Caucasian ancestor”. They only catered to those with “the right background and look” as an estimated “80 per cent of students were light-skinned and of mixed heritage”. Fraternities and sororities at these universities also only catered to those with light skin and “good” hair, and many of their student parties chose attendees based on the “ruler test” where only “partygoers whose hair was as straight as a ruler would be admitted”.

The same went for places of worship where morality and good character were measured by proximity to physical whiteness. Entry into the church service was only admitted if the churchgoer passed the paper bag test, a test that measured skin tone by comparing it to a brown paper bag – if you were any darker than the paper bag then you would be refused entry. Another test was the comb test. According to both Byrd and Dabiri, the comb test, a prelude of the Texturism we see today, measured the level of kink in the hair. If the comb could pass through the worshipper’s hair without getting snagged on a kink, entry was given; if not, entry was denied.

And whilst all of this is most certainly unfortunate, it is important to remember that in a society where Black is at the very bottom, any means by which to climb a rank or two higher would have been taken. Many Black people were still working on plantations after abolition, despite the change of laws, for lack of a place to go. The introduction of new vagrancy laws also prevented mobility and can be seen as a precursor to the school to prison pipeline system currently in the US today. It shouldn’t, therefore, be surprising that those who could avoid this, by displaying their loose curl patterns and lighter skin, did everything in their power to do so.

Around this time, more Black people – women in particular – were beginning to tap into the emerging market of skin bleaching creams and hair straighteners to distance themselves from their African heritage and gain more class mobility. Companies arose to meet the needs of the new Black consumers who now had a little more money in their pockets.

Black Entrepreneurs

At the turn of the 20th century this “new negro era” gave birth to an entirely new concept: the Black entrepreneur, someone who could see the potential and willingness of the new Black consumer to spend their money to get ahead in the new world. The Black entrepreneur knew their customers and knew that the one place Black people would turn to time and time again, to attempt to better their situations in life, was hair. Two of the most famous figures to come into this space were Madam C.J. Walker and her mentor Annie Malone.

Annie Minerva Turnbo Malone, who had a background in chemistry, began thinking about ways to aid the growth of the hair of women who looked like her and who commonly suffered from baldness and hair breakage due to their difficult lifestyles and inabilities to access a proper diet and hygiene. Dissatisfied with the range and availability of hair care products and styles for Black women, Malone sought to find a way for women like her to improve their standing in the world by making their hair more “manageable” and improving its quality. In the 1900s Malone claimed that she would revolutionize Black hair growth with her “miracle hair grower” which she started selling door-to-door in Illinois, marketing it as a “miracle cure” under her company Poro.

One of her sales girls was a young woman called Sarah Breedlove, later Sarah C.J. Walker. Breedlove was born on a cotton plantation farm in 1867 and came to Malone after suffering severe hair loss as a physical response to a mental breakdown caused by her first divorce and her long, hard labouring hours as a washerwoman. Breedlove believed, like many other Black women of her generation, that if she could improve her hair, she could improve her life. So, Breedlove started buying Malone’s Wonderful Hair Grower to improve her hair and her life. She became a Poro saleswoman to Malone’s clients, selling the Wonderful Hair Grower, presumably by telling them her story of failure and success through hair. But Breedlove’s success with Malone’s hair grower is as much a story about representation as it is about Black entrepreneurship.

Annie Malone c. 1910

Sarah Breedlove/C.J. Walker c. 1914

C. J. Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower in the permanent collection of The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis

C.J. Walker driving with friends c. 1911

Malone managed to achieve her success because she was speaking to a generation of women who had never had anyone take interest in their beauty standards before, and they had never had anyone who looked like them telling them that they could achieve beauty. Breedlove’s success came from sharing her story of hard work, hair loss and depression – a story that many women at the time would have been familiar with. Indeed, the benefits of the hair grower were clearly visible on Breedlove, a woman who looked, felt and experienced life like them. She had stronger hair, greater confidence and a job, which convinced her customers that they could experience these results for themselves.

Breedlove, by this time Walker, taking the name of her third husband, went on to create her own hair care empire to rival Malone’s. And it was because of this idea of representation, and relatability, that Walker was able to do this.

Walker took Malone’s hair grower and went on to create her own line of Walker System hair products. It started with the shampoo-press-and-curl: a “method of hair straightening that was to become the foundation of the Black beautician industry”. Into this system, Walker gradually included Hair Grower, a pomade called Glossine, Vegetable Shampoo, Tetter Salves and Temple Grower. For her salesgirls, Walker provided a training course kit which included a hot comb, the tool Walker was credited with introducing to the US market. All of these products were designed to help with the specific hair needs of the “New Negro Woman”.

These events were dramatized by Netflix in their 2020 drama series Self-Made which centres around the growth of the Walker hair company and the rivalry between Walker and her former mentor Annie Malone. The Netflix show makes it very clear that Annie Malone, refashioned as Addie Monroe, is a “light bright”, “high yellow woman” profiting off the insecurities of other Black women. In the show, Addie Monroe, played by Carmen Ejogo, uses her own straight, long, mixed hair as the archetype, and uses only fair-skinned, straight-haired women for her advertising and door-to-door sales, forcing all Black women who come to her to aspire to look like her, while knowing that most of the time this is unattainable. As a result, Monroe manages to consistently profit from her clients’ adherence to an unattainable beauty standard and she revels in being the poster girl for that beauty standard. In contrast, Walker, played by Octavia Spencer, is a darker-skinned, Afro-hair textured Black woman out to better the lot of all Black women everywhere by showing them their own African beauty, rather than demonstrating to them how far from the ideal they are.

Contrary to what Self-Made would have us believe, the reality was not so black and white. Malone was not a lighter-skinned Black woman out solely to profit from her clients’ insecurities, nor did she set herself up as the epitome of beauty. And Walker was not a benevolent manufacturer out solely to better the community. She was a businesswoman and, as such, was out to make a profit in the same way as Malone by focusing on the insecurities of her clientele.

Walker, again using her relatability to her clients, played on the common preoccupations that come with having non-standardized hair types and used that knowledge to draw her customers in. A 1920s Walker advertisement poster featured a beautiful woman, a flapper, standing at a mirror admiring herself, as do many adverts aimed at women, even today. The advert was depicted as an engraving, so the colouring of the woman is unclear, but it is fair to assume that the woman in the image is lighter-skinned. The figure’s hair is quaffed in a 1920s flapper style, a common style for women of the time, and does not celebrate Afro hair. Coupled with the bold assertive title, “You, too, may be a fascinating beauty”, there is a clear implication that by purchasing Walker’s products you can come to look like the woman in the advert.

There has been a lot of criticism concerning these messages that Walker and Malone provided, claiming that they were “telling Black women to straighten their hair”. On the one hand, the relaxer now allowed Black women to gain the “neatness” that white beauty standards demanded of them, but it also meant that the emphasis had now shifted from trying to love their hair in its natural state to, once again, venerating and emulating the white ideal. And many people were very aware of the double-edged nature of Black hair care. The right hair could easily be obtained, even if it was to the detriment of your real hair, and was obtained by a whole generation of women to help them live their lives as best they could. But gaining that kind of hair left many women disillusioned with their heritage. They could not see the beauty of that heritage because they had been taught to hate their hair and were given a quick fix solution on how to eradicate it.

Because of this double bind, hair became the focal point and, in a way, the byword for Black identity more generally in the years after the abolition of slavery, right up until the start of the Civil Rights Movement. It became a means of sympathizing with Black women, telling them not to be a slave to white standards, but it also became a way of ridiculing them for the internalization of these standards.

Black Activism

Popular activists like Malcolm X (below) and Marcus Garvey were very vocal about this fact. Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican pro-African activist and leader of the United Negro Improvement Association, in a speech asked his listeners not to “remove the kinks from your hair” but “from your brain”. Many Black newspapers, such as the Crusade, and Black ministers provided that same message to their readers and congregations, admonishing them for engaging in “unnatural and ungodly habits”.

These same sentiments were echoed by Malcolm X whose views are all the more believable and poignant. Though male, X had experienced all three states of the Black hair journey that many Black women transition between in their lifetime: natural, relaxed/permed and back to natural. Although relaxing was more popular amongst men at that time than it is now, it was still a predominantly female practice and few men were writing about their experiences with hair. Because of this, X’s testimony can be used to understand a little bit about the psyche of the Black people who relaxed their hair and then gave up the practice.

Malcolm X said: