22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Knitting has long been celebrated as a therapeutic and creative experience, which can produce many unique and eye-catching items. In Hand Knits for the Home and Garden, experienced designer Alison Dupernex shares the secrets of how to work with the head, heart and hand in tune, combining stitch choices, colour, material and skilful execution into one design. This beautiful book of projects offers an extensive collection of patterns for domestic furnishings and household items. With practical advice and further ideas for each project, it can be used as both a tutorial and a catalyst for developing individual style and original pieces of work. Supported by over 150 colour illustrations, this detailed guide offers finishing techniques and includes over 40 patterns for cushions, throws, pots, lampshades, rugs and other fun projects such as covers for hot water bottles and deck chairs. Written for dedicated hobby knitters and professional knitters.The patterns include cushions, throws, pots, lampshades, rugs, deck chair covers and cards. Each project is supported by colour illustrations - there are 164 in total. Alison Dupernex is an experienced designer and her patterns have been widely published by magazines.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

HAND KNITS FOR THEHOME AND GARDEN

Alison Dupernex

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

© Alison Dupernex 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 456 8

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks are due to Rowan Yarns for keeping up with my demands for yarn. I thank Knoll Yarns for sponsoring the Aran-patchwork blanket and Chris Birch for help with the knitting. Also, thank you to Sharon McSwiney, jeweller and metal worker, and Gilly, from Yew Tree Gallery, who allowed me to use their gardens, in sunny Cornwall, to photograph some throws. Huge thanks to Simon for reading and making sense of the hieroglyphs. I have had some wonderful support.

CONTENTS

Introduction

1Yarns and tools

2Techniques and stitches

3Cushions and pillows

4Throws and blankets

5Pots and vessels

6Lampshades

7Rugs, runners and mats

8Gift ideas

9Designing with colour

Appendix Embellishments and additions

Further reading

Contacts and suppliers

Index

INTRODUCTION

It is a very human characteristic to want to create something, and the act of creation in turn is hugely satisfying.

This book is to be used as a catalyst for your ideas. There are patterns, but the hope is that you will be inspired to adapt these or make up your own, gaining in confidence and knowledge. Colour is talked about at great length, as it is the use of colour that raises a great deal of work above the ordinary.

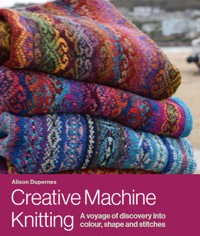

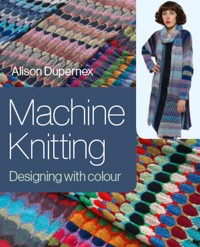

Textured and Fair Isle blankets.

The joy of making some furnishings is that you do not have to get too hung up on sizing and gauge/tension. For many of the projects, such as blankets, throws and runners, it really is not important if the finished result is a few centimetres larger or smaller than the sample. However, accurate sizing is important when making a box covering or a cushion cover, because exact dimensions are required for these items to be functional.

Head, heart and hand

These three aspects are the basis on which all design is created.

Your head asks logical questions. What colours should I use? What is my project? What stitch pattern should I use? What are the likely problems that I may encounter? How will I solve them? This also covers the practical side of the design and how it will be worked.

Your heart triggers emotions and feelings, leading to further design questions. Why should I use a certain colour? Can I not experiment and take a risk? Is my experiment successful? How tactile is my project: is it smooth and soft or bobbly and crunchy? Which options will work best for my design?

Your hand is how you can obtain the results required, by the execution of the project. Your hands are the tools for the job, and what wonderful tools!

You are standing on the shoulders of giants, and many well-known knitters have explored and developed the techniques that you will use as a keystone for further creative development.

The history of humankind has been and still is a violent one; yet, while one section of humanity is prepared to behave in utterly inhuman ways, there is another that has quietly continued to develop their practice and build on their skills as creative makers. Your philosophy of making feeds a calm, meditative core, which is hugely satisfying, and this philosophy will run through your veins like a life blood and help to make the world a more civilized and contemplative place.

In recent years, there has been a resurgence in the practice of hand knitting, and there are many reasons to explain why. The hectic pace of life requires moments of calm, and knitting, being portable and requiring just two sticks and some wool, is an ideal way of achieving this. Knitting is versatile and, when it is being performed, a calming rhythm is built up. There are no boundaries, and a pattern can be followed closely, stitch by stitch, or the maker can take flight and add stitches and change colours. Your confidence grows, and you will invent new techniques.

Seascape deckchair cover.

Even with the finest yarn, it is the quality of your design and technique that will make a work of beauty. Do not be anxious or reluctant to unpick your mistakes and start again, because this is all part of the learning process and will pay dividends in terms of your completed design. Some mistakes can be happy accidents, but not all, so do not be afraid to experiment!

Bring your knitting to life by always considering how it can be made better, and experiment with innovative details, because this will extend your skills.

With the head, heart and hand all employed, knitting really does become a therapeutic and creative experience; many knitters have known this for generations, but for others it is a new understanding.

A short history of knitting

The true history of knitting is lost in the mists of time, but there are early examples from the Near East. Fragments of knitted textiles, socks, to be precise, have been found in Egyptian tombs, and these were knitted in the round and feature two colours of yarn. They have been dated between 1200BC and 1500BC and show that the knitters of that time were making practical items and designing their own stitch patterns, echoing intricate woven-carpet borders.

Rare examples have also been found in Spanish tombs, dating from the thirteenth century: they are exceptionally finely worked, with intricate two-colour patterns showing a strong Arabic influence, and a gauge/tension of twenty stitches per 2.5cm (1in). Many of the early examples have survived because they were made for occasional liturgical use.

Historically, knitting was a male craft. During the European Middle Ages, a knitter’s apprenticeship was served over three years, and another three years of travel was undertaken to explore and learn new patterns and techniques. The degree of refinement attained was exceptional, and, to become an accredited knitter and join a guild, which was essential to gain work, an exam had to be passed. A number of original ‘masterpieces’ had to be designed and knitted in a short time: a felted cap, a pair of stockings or gloves with a decorative pattern, a shirt or waistcoat, and a carpet or hanging of 183cm × 152cm (6ft × 5ft), to show off the skill of patterning flora and fauna. The mind-boggling intricacy required indicates that these items may have been made on a knitting frame. Only when this process was completed and passed did the knitter become a master. The intricate and exquisite garments were worn by members of the nobility, and each had his own favourite master.

There is evidence from England to suggest that complex knitted caps were made in Coventry during the thirteenth century, such as the Monmouth cap: this was worked with stocking stitch being knitted with four needles, and the rough, coarse wool was then felted. This style of cap was still being made in the nineteenth century for soldiers engaged in the Crimean War. The makers of these garments were called Cappers and worked full-time for the production of these caps.

Finely decorated hose were fashioned for men to show off their legs, and the English monarch Elizabeth I is said to have imported knitted silk stockings from Spain. The demand in Tudor times then grew for finely knitted garments, and pantaloons were also made with slashes to reveal not only lace patterns but delicate knit-and-purl patterns.

In his book A History of Hand Knitting, Richard Rutt discusses the colour of men’s stockings in France in the early seventeenth century. He cites evidence in a satirical novel of the time that mentions wonderful, evocative shades such as Dying Monkey, Merry Widow, Resuscitated Corpse and Sad Friend! There are examples of hose in shades of pink and beige, which would fit with these descriptive and expressive names.

Hose became an important fashion statement during the seventeenth century, depending on whether they were made from wool or silk, with those hose made from silk being perceived to belong to wearers of higher social status than those made from wool. The colour of the hose also had great social significance, and members of Oliver Cromwell’s Parliament of 1653 were called ‘blue stocking’ as a term of abuse. Later, blue and grey became unfashionable, because they had puritanical overtones. Over a century later, ladies clubs too were called blue stocking after scholar Benjamin Stillingfleet appeared at one of Elizabeth Montagu’s assemblies wearing blue worsted stockings, instead of the more socially acceptable white silk. The term is still used today in an unflattering way, to describe an educated, intellectual woman.

Many hundreds of knitters were employed making hose, so it was not popular when, in 1589, a curate by the name of William Lee devised the first stocking-frame knitting machine to speed up the slow manufacturing process. The English monarch Elizabeth I refused him a patent twice, and she expressed her concern that many of her subjects would become beggars and the skills of the artisans die out. This backlash was instigated by the Hosiers Guild whose job it was to protect the livelihoods of the sock and stocking makers. After one disastrous partnership, William Lee went into another with his brother and moved to France, where the French monarch Henry IV granted him a patent. He found success for a few years, having started up an industry in Rouen; however, with Henry’s assassination in 1610, Lee’s fortunes plummeted. He died in 1614 in penury.

Lee’s brother, James, returned to England and started a partnership with a previous apprentice of William’s, and two centres were established, one in London and another in Nottingham, to produce knitted hose using the industrialized framework-knitting process. During the eighteenth century, there was fierce competition between the centres in Leicester and Nottingham as to who was the leader of this industry.

Although it took nearly a hundred years, a thriving industry using wool, silk yarn and knitted lace fabric was established in England. The machinery that Lee developed was hugely important and created a firm foundation for the textile industry for many years to come.

King Charles I of England is said to have been executed while wearing a delicate knit-and-purl-decorated silk shirt. Many garments of this era were made with two colours of thread, one of which was metallic, used specifically to imitate jacquard woven fabric.

The Worshipful Company of Framework Knitters was granted a charter in 1657 under Oliver Cromwell, but machine knitters were no real threat to hand knitters for at least another two hundred years, because hand knitting was both fast and cheap. It was only with the introduction of man-made fibres and the increase in the demand for knitted fabrics that hand-knitting jobs were threatened.

A Dutch knitted wool petticoat dating from the eighteenth century can be seen at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London; measuring 317cm (125in) in circumference and with a depth of 76cm (30in), it is covered with geese, alligators, rhinoceroses, wild boar, dogs and myriad other animals worked entirely with knit and purl stitches. No animal is repeated, and there are approximately 2,750 stitches per round. The detail and finesse of the work is such that it would not be possible to technically produce a work of this calibre today, because of the loss of skill.

Lace knitting had been popular in Europe since the fifteenth century, when silk yarn became more widely available. The action of knitting two stitches together and yarn over (yo) makes a small hole and, when knitted with a fine silk yarn, can create beautiful, delicate openwork scarves, gloves and hose. Lace knitting continued to grow in popularity. When, during the eighteenth century, cotton and muslin threads were imported from the East, the fashion was for ‘white knitting’; this was produced using thread, finer than sewing cotton, knitted with fine wires and on the thinnest of needles. At this time, aristocratic ladies worked the most exquisite examples of white knitting in the form of samplers, and, by the mid-eighteenth century, knitting had become a pastime, not a necessity, and was practised by all social classes.

While this revolution was taking place, in the rural counties knitting was being developed and practised by country folk as a way to make money. Whole families worked on knitting garments for sale, because knitting was easy to pick up and put down, and all the tools were readily available and inexpensive. Each member of the family was expected to make a pair of hose a week. Women, men and children would all walk, herd, and talk as they knitted. A yarn rattle would be wound into the centre of a ball of wool so that the ball could be found in the winter months if it rolled into a dark corner. Sailors and fishermen developed their own patterns; it was the women’s task to spin the yarn, and the men, whose nimble fingers were used to knotting nets and tying ropes, were the knitters.

The men of the Aran Islands developed their own unique patterns, and today the Aran sweater has become a generic term for a cable-knit garment. Very often, a deliberate mistake was inserted into the pattern, as the culture was deeply religious, and nothing was supposed to be perfect except for God.

It is often thought that families had their own stitch patterns, and how the pattern was placed in relation to another pattern denoted where the sweater came from and even who had knitted it, which could prove to be useful information. If the wearer of a sweater fell overboard and was washed ashore, they could be identified based on the sweater’s stitch patterns; however, this is sadly an urban myth, but it is such a romantic idea that it is still often repeated as fact.

As the colonial expansions of Britain and other European countries gained pace, the skill of knitting as practised in Europe spread to other parts of the world. In America, boys and girls went to knitting school to learn to make socks and gloves, and, during the American Civil War, it was seen as patriotic to knit comforts for the troops. Missionaries also spread the craft to China and Japan, and the practitioners in these countries have become experts in this field.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, knitting yarns became softer, following the introduction of merino wool. As yarns became more widely available, the mechanized framework knitting machine became ubiquitous. Knitting was no longer exclusively thought of as a craft of the poor but as part of the first Industrial Revolution.

Middle-class ladies, however, continued to make exquisite beaded purses, mufflers, shawls and even dresses. It was during this time that many of the patterns that are used today were incorporated into the canon of work: Fair Isle patterns, Aran cables and patterns, Shetland lace, and the Scandinavian-colourwork lice patterns, to name but a few.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, commercial knitting patterns began to be published, and magazine issues were brought out monthly to encourage knitters to make a variety of items from toilet-roll holders in the shape of a poodle to intricate twisted-stitch jackets. In 1906, abbreviations such as ‘ss’ for stockinette stitch were first used.

In the nineteenth century in the Shetland Islands, wool was spun into the finest of threads and worked into delicate shawls, which it was said could pass through a wedding ring. Queen Victoria and other members of the royal family were seen wearing these shawls, which sealed their popularity. Queen Victoria was herself a knitter and ‘recipes’ were published to fuel the interest in knitting: patterns for bags, pin cushions, baby clothes, shawls and many other accessories were made available, with some examples being technically sophisticated. Tension and needle size were not the issues that they are today; what was important to the knitter then was the practicality of how to make the garment and the stitch pattern.

There was a complete explosion of knitting in the home during the First World War. Patterns were adapted, and parts of different patterns were incorporated into single pieces of work: it was a real melting pot. Wives, mothers and sweethearts knitted gloves, hats and many other items to be sent to their loved ones in the conflict areas, because this provided comfort and solace to both the knitter and the soldier.

Around the same time, in India, paisley designs were used as motifs on caps; in South America, hats and leggings were made that emulated indigenous woven designs; and all over the world hats, gloves, sweaters and coats were made, with each nation having its own particular signature motif. In the British Isles, the wealthy aristocracy saw the home production of knitted garments as a way to keep the street urchins from the workhouse.

In the early twentieth century, the English aristocracy also encouraged the knitting industry of the Shetland Islands, by wearing the sweaters produced there and so making them fashionable. Edward, the Prince of Wales, famously wore a Fair Isle sweater; he had his portrait painted by John St Helier Lander in 1925, showing this garment, which he had worn to the opening of the golf season at St Andrews golf course, Scotland, in 1921. The bright pattern of the sweater reflected the jazz age and was picked up by Coco Chanel, and its place in history was assured. The unique and distinctive character and vibrancy of the pattern meant that it was highly adaptable and has never been out of fashion.

Fair Isle designs featured natural colours found in sheep’s wool; later, natural dyes of browns, soft greens, ochre and indigo were all used, up until the Second World War. Then, the background colour began to change, making rich stripes of Fair Isle and bands of subtle wave patterns in colours of similar shades that were placed at the top and bottom of OXO patterns, which added to the intricacy and originality of each garment.

Knitting from around the world.

The first recorded cable-knit sweaters were made in the early twentieth century on the Irish Aran Islands of Inishmore, Inishmaan and Inisheer, and they were made fashionable in the 1960s by the author Heinz Edgar Kiewe, who wrote The Sacred History of Knitting in 1967. He found a creamy white sweater with cables, twisted stitches and bobbles in Dublin in 1936 and became a passionate advocate of this style of garment and the techniques involved in the production of these sweaters.

Many other patterns were created over the years, and moss stitch, trellis stitches and small and large cables all add to the unique style of the cable-knit sweater. There has been and continues to be much discussion as to the true origins of this garment, but the techniques and style appear to be relatively recent. By 1954, there were many examples of this distinctive patterning, and it has brought welcome work to the people of the Irish islands. The cable-knit sweater has been popular since its first discovery and has never fallen from favour, which demonstrates the enduring, attractive quality of the stitches.

New techniques are being developed all the time, and one such example is mosaic knitting, advocated by designer Barbara Walker. The interplay between slip stitches, knit and purl stitches, and various colour changes produces a distinctive, textured fabric when using this technique.

The fortunes of hand knitting have waxed and waned, even though the expensive, leading fashion houses have constantly kept knitting in their collections: Elsa Schiaparelli made the iconic sweater with a trompe l’oeil bow in the 1920s, Coco Chanel has repeatedly used panels and blocks of knitted fabrics in her designs from the 1920s onwards and, post-2000, Vivienne Westwood has crafted clinging lace panels, delicate flowers and Fair Isle patterns, all on the same garment. Knitting is a truly versatile medium that will continue to be used, because it allows makers to produce designs that are fashionable, exciting and innovative.

As a reference, small pieces of knitting can be collected, and there are various fairs and vintage sales that you can visit to buy these treasures. Sadly, many older pieces have been lost because of moth damage.

The featured little waistcoat from Pakistan, worked with cotton, has the most eye-catching and vibrant colours: note the innovative use of a zip for the edging. The Peruvian hat, while more sober in colour, is extremely finely knitted, using traditional patterns.

By having a better understanding of the historical perspective of how knitting has developed, you can better appreciate the rich diversity of the designs that you can create through the application of the different influences that inform and inspire your work.

This first chapter has introduced you to some of the key ideas that go together to create good knitting-design practice, and my hope is that you will be inspired to assimilate and adapt these ideas on your design journey, gaining in confidence and knowledge, to produce work of exceptional quality.

Making knitted furnishings allows you to have great flexibility in the design process, with your flair and imagination at the forefront.

Please use the designs and ideas presented in this book as inspiration for your own projects.

CHAPTER 1

YARNS AND TOOLS

Yarns

No amount of excellent knitting will increase the quality of inferior yarn. There are many varieties of yarn available; whether your preference is for wool, cotton or silk yarn, or a yarn featuring a combination of materials, there will be a good choice available. All of the above yarns are spun from a fibre, and how they are spun will indicate the finished look of the yarn and knitted fabric. The fibres are all spun from filaments or staples. Filaments can be continuous in length and are mainly synthetic, the only exception being silk. Staples are shorter, and the spun yarn is made up of many short strands. The longer-staple merino wool and Egyptian cotton spin into smooth, good-quality threads.

Textured throw in the rugged landscape that inspired its design.

A variety of yarns.

All fibres fall into two categories: natural or synthetic.

Natural fibres

These are subdivided into two categories: animal proteins and vegetable cellulose.

Animal proteins include mohair, wool, alpaca, cashmere, angora and silk fibres.

Vegetable cellulose includes flax (linen), cotton, sisal, hemp, bamboo and jute fibres.

Sadly, moths love all animal fibres, and their larvae feed off the proteins that these fibres are made of. If it is suspected that the yarn or knitted fabric has been attacked by moths, place it in the freezer for two weeks; this will kill any larvae.

Synthetic fibres

Yarns made from synthetic fibres such as nylon, acrylic and polyester were primarily developed and popularized after the Second World War. They are made from a variety of mineral sources, the main exception being viscose rayon (or artificial silk), which is derived from cellulose and was developed in 1894 by the English chemists Charles Frederick Cross and Edward John Bevan.

The yarn that you select will determine the finished quality and character of your project. Most yarns are denoted by their count number (or thickness). The standard system in use today is the ‘new metric’ (Nm) system.

The Nm count number indicates the length in metres of one gram of yarn. So, for instance, 1g of 11Nm yarn will be 11m long, and 1g of 1.6Nm yarn (aran weight) will be 1.60m long.

Diagram of S and Z twist.

Under this system, two ends of 1.6Nm yarn placed together would be equivalent to a single yarn of 0.8Nm. When yarns in lengths are twisted together, they are denominated as ‘ply’, and two-, three- and four-ply indicate how many lengths of yarn have been twisted or plied together within each yarn. The Nm count number indicates the length per gram of yarn: the lower the Nm count number, the thicker and heavier the yarn and the smaller area of fabric that you can knit per gram of the yarn.

The choice of needles depends on how firm or loose the resultant fabric needs to be. So, an average knitter working with aran-weight yarn could use a 5.5mm (US9, UK5) needle, but a tighter knitter could use a larger 6mm (US10, UK4) needle to obtain the same results. Your needle selection is an indication of the weight of the fabric being produced, combined with the tightness of your knitting.

Spinning twists the staples or filaments together into a spiral; a twist to the left is called an S twist and to the right is called a Z twist. The resultant spirals of yarn can then in turn be further twisted together to be plied into a thicker, stronger yarn.

Yarns spun from wool are either worsted or woollen. Worsted yarn is spun from longer staples that are combed to make the fibres lie straight against each other, in parallel, which produces a firm feel for the resulting yarn. To produce woollen yarn, wool fibres are carded, to clean and untangle the shorter fibres, and are then rolled into a loose sausage shape, which is then drawn into a yarn by spinning. Woollen yarn is not as strong as worsted yarn.

Bamboo, sari fabric, paper, ribbon and many other variations of yarn are available for you to work with.

There are also many different finishes to yarns; for example, ‘superwash’ yarn can be washed in a washing machine and subsequently be dried without the yarn shrinking, and mercerization adds strength and lustre to cotton.