Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

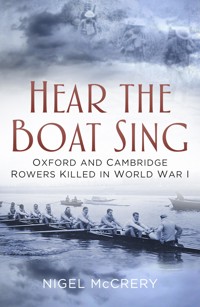

During the First World War many sportsmen exchanged their sports field for the battlefield, switched their equipment for firearms. Here acclaimed author and screenwriter Nigel McCrery investigates over forty Oxbridge rowers all of whom put down their oars and gave their lives for their country. Complete with individual portraits, these brave men are remembered vividly in this poignant work and, together with a new memorial to be unveiled at the 2017 Boat Race, there is no more fitting tribute to these men who made the ultimate sacrifice.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HEAR THE BOAT SING

For Rebecca and Joe, with all my love. You have brought me nothing but pleasure and pride.

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

© Nigel McCrery, 2017

The right of Nigel McCrery to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8198 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

1 Hugh John Sladen Shields

2 Reginald William Fletcher

3 Bernard Ridley Winthrop-Smith

4 Cyril Francis Burnand

5 Samuel Pepys Cockerell

6 Gilchrist Stanley Maclagan

7 Henry Mills Goldsmith

8 Oswald Armitage Guy Carver

9 Richard Willingdon Somers-Smith

10 George Eric Fairbairn

11 Wilfrid Hubert Chapman

12 Edward Gordon Williams

13 Dennis Ivor Day

14 Charles Ralph le Blanc-Smith

15 Arthur John Shirley Hoare Hales

16 Geoffrey Otho Charles Edwards

17 John Andrew Ritson

18 Thomas Geoffrey Brocklebank

19 John Julius Jersey De Knoop

20 Lancelot Edwin Ridley

21 Evelyn Herbert Lightfoot Southwell

22 Richard Philip Stanhope

23 Charles Pelham Rowley

24 Auberon Thomas Herbert

25 Frederick Septimus ‘Cleg’ Kelly

26 Mervyn Bournes ‘Buggins’ Higgins

27 Arthur Brooks Close-Brooks

28 Robert Prothero Hankinson

29 Alister Graham Kirby

30 Kenneth Gordon Garnett

31 Cecil Pybus Cooke

32 Roger Orme Kerrison

33 Duncan Mackinnon

34 George Everard Hope

35 William Augustine Ellison

36 Graham Floranz Macdowall Maitland

37 William Francis Claude Holland

38 Ronald Harcourt Sanderson

39 James Shuckburgh Carter

40 Edward Parker Wallman Wedd

41 Edouard Majolier

42 William Alfred Littledale ‘Flea’ Fletcher

Appendix 1 History of the Boat Race

Appendix 2 The Race Course

Appendix 3 Rowing Terms

Appendix 4 List of Names

Appendix 5 Boat Race Results 1829 to 1920

Appendix 6 Rowers by Boat Race Year

Appendix 7 Rowers by College

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

My many thanks go to: Alan Clay, historian and researcher; Ashley McCrery for advice and research; Richard Black and Roan Hackney, London Medal Company; Hal Giblin, my inspiration; Dennis Ingle, for his hours of calm advice; William Ivory, friend and advisor; Phil Nodding, friend and advisor; Pearce Noonan, Nimrod Dix Auction House; Richard Steel for hours of calming advice and for being one of the kindest people I have ever met, a very true friend; Great War Forum; M. Brockway; R. Flory; Charles Fair; Heritage Plus (first-class research); R. Braverei; Patrica Anne Pedley; Tom Gooden; Kate Wills; IPT; L. Booth; Izzy Melliget; John Hartley; J.D. Ralph; D. Owen; Coldstreamer, tullybrone; Medals Forum; Cambridge University; Oxford University; Trinity College and Trinity College Boat Club; Jesus College, Cambridge; Balliol College, Oxford; Magdalen College, Oxford; Merton College, Oxford; St John’s College, Cambridge; Lady Margaret Boat Club; Corpus Christi, Oxford; New College, Oxford; Trinity College, Oxford; Christ Church College, Oxford; University College, Oxford; Brasenose College, Oxford; King’s College, Cambridge; Caius College, Cambridge; Christine McMorris, my editor, for all her hard word and sound advice; The History Press for agreeing to publish the book; Michael Leventhal for agreeing to take the book on; ‘Hear the Boat Sing’ and Göran R. Buckhorn; Putney Council London; Diarmuid Byron O’Connor; Richard Parkin, friend and the person I’ve been closest to for over fifty years, who is still looking after me – without you life would be a much greater struggle; Nelly Khmilkovska for her time, beauty and patience; Professor John Lonsdale, Trinity College, Cambridge, for changing my life; eBay, one of the finest sources of photographs, books and information on the subject I have ever found.

If there is anyone I have forgotten I can only apologise and I promise to put you into the next edition.

Foreword

I’m a big believer in the saying that history is ‘us then’. When writing any of these books, I find myself becoming emotionally involved with the characters I am writing about. In the case of the Oxbridge rowers, for me it becomes even more poignant. I was lucky enough to go to Trinity College and know many of the Boat Club rowers. Young, full of energy and with a zest for life that I had rarely experienced before. Most have gone on to achieve remarkable things in the worlds they have chosen and are a credit to the country they live in. The rowers of 1914–18 never had that chance, their lives cut short before most had chance to achieve anything. For me the epitaph (from Henry V by William Shakespeare) on Raymond Asquith’s grave (son of the prime minister) sums up my feeling on the loss of these young men: ‘Small time, but in that small most greatly lived this star of England.’

We lost around 1 million people during the First World War and when dealing with numbers like this we are in danger of seeing them as numbers not as people. People who had lives, were loved and loved. To this end, I hope the book will at least help people remember that and remember them so they do not die in memory.

Because of the nature of the book there has been some repetition when talking about the various Boat Races, as several men from particular boats were killed, such as the five rowers from the 1914 race. This way you can dip into the book or, if reading from beginning to end, just skip the race you have already read about. I am sure, although I have tried to avoid this, I will have made some mistakes and apologise for this in advance. If you feel I might have missed someone please make your case and I will consider including them in future editions.

I also make one small request: whenever you take a group photograph please name the people in the picture in some kind of order. It really helps later generations. More than anything, I hope you enjoy Hear the Boat Sing and it makes a good reference work for future generations to read, consider and, most of all, remember.

Nigel McCrery, 2017

1

LIEUTENANT HUGH JOHN SLADEN SHIELDS

Boat position: Stroke

Race: 67th Boat Race, 23 March 1910

College: Jesus College, Cambridge

Served: Royal Army Medical Corps, attached to 1st Battalion, Irish Guards

Death: 25/26 October 1914, aged 27

He died, killed in action doing his duty, like the brave man he was.

Hugh John Sladen Shields (more popularly known as ‘Willoughby’, a nickname he picked up at school) was born in Calcutta in India on 16 June 1887, the eldest son of the Reverend Arthur John Shields, later rector of Thornford in Dorset, and Mary Forbes, daughter of the Reverend W.B. Holland, rector of Brasted, Kent. Hugh was educated at Orleton Scarborough, before being sent to the Loretto School, Musselburgh, Scotland, where he was a prefect and boarded between 1899 and 1906.

Hugh John Sladen Shields.

From Loretto he went up to Jesus College, Cambridge to read Natural Sciences. A practising Christian, he was a committee member of the Cambridge Church Society and took part in philanthropic works in both Cambridge and London, giving up many of his evenings and weekends to assist in good causes in Camberwell. The Reverend E.G. Selwyn (the warden of Radley College) later said of Shields:

I always felt about him at Cambridge that he was absolutely fearless about his religion – not a common thing in that atmosphere; and that the thing he cared most about was the service of his Lord and Master.

A fine all-round sportsman, he was soon in the college’s first XV where he was described as a very talented player – ‘the cleverest of the forwards’, as someone later wrote. He later became captain of the XV. In 1908 Shields rowed in the ‘rugger boat’. He enjoyed the experience so much he began to take his rowing seriously, improving to such an extent that he was selected to stroke for the Cambridge crew during the 1910 Boat Race.

67th Boat Race, 23 March 1910

The Oxford coaches were G.C. Bourne (New College), who had represented them between 1882 and 1883; Harcourt Gilbey Gold (Magdalen), who represented Oxford University on four occasions between 1896 and 1899 and was also president of Oxford for the 1900 race; and W.F.C. Holland (Brasenose), who also rowed for Oxford on four occasions between 1887 and 1890. Cambridge was coached by William Dudley Ward (Third Trinity), who rowed for Cambridge in 1897, 1899 and 1900; Raymond Etherington-Smith (First Trinity), who had represented Cambridge in 1898 and 1900; and David Alexander Wauchope (Trinity Hall), who had rowed in the 1895 race.

The race was controversial from the start. As a result of ‘awkward’ tides it was decided to hold the race in Holy Week. This caused a great deal of disquiet amongst several of the Christian rowers (including Shields) and controversy in the papers. For a while it looked like the race either wouldn’t go ahead or its date would have to be moved. It wasn’t until the Bishop of Bristol gave his permission, under the express condition that there weren’t any celebrations after the race, that the event went ahead. As a committed Christian it would have been doubtful whether Shields would have taken part even if the race had gone ahead.

Race day was beautiful with a warm sun and a mild breeze. Cambridge won the toss and chose to take the Middlesex station, with Oxford on the Surrey side. For the seventh year in a row Fredrick I. Pitman (Third Trinity) was umpire; he had rowed for Cambridge in 1884 (Cambridge), 1885 (Oxford) and 1886 (Cambridge). Pitman, to the cheers of the assembled crowd, started the race promptly at 12.30 p.m. Cambridge made a quick start and began to leave Oxford behind until one of the Cambridge crew caught a crab and the Oxford crew pulled quickly past them. By Craven Steps, and despite being the slower boat, the Oxford crew were ¼ of a length ahead. However, Cambridge put on a spurt and by the Mile Post were in the lead. But the Cambridge crew began to lose ground to Oxford as they rounded an unfavourable bend in the Thames. Oxford began to push hard, gaining a length in 10 strokes. By The Dove pub, Oxford had a 1-length lead, which they finally extended to a 3½-length lead by the end of the race. Their time was 20 minutes 14 seconds, the slowest winning time since 1907. Oxford’s overall lead was now thirty-six to Cambridge’s thirty.

Hugh John Sladen Shields.

***

In the same year, rowing with Eric Fairbairn (Jesus), Shields won the Lowe Double Sculls. He also rowed at Henley in the Jesus Grand Challenge Cup crew, and was runner-up for three years in succession. He did, however, win the Ladies’ Plate in 1905. He also rowed No. 2 in the Jesus boat, which against all the odds won the International Race at Ghent in 1911 against a Belgian crew which had never been beaten before.

In 1910 Shields graduated with honours in Natural Sciences, going on to become a ‘scholar and a prizeman’ at Middlesex Hospital, where he also captained the XV. He became a Bachelor of Medicine in 1913.

Having always been interested in military matters, Shields was commissioned into the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1912. In 1913 he boxed as a light heavyweight for the army and was runner-up at his weight, being beaten by fellow RAMC officer and rower M.R. Leahy, a former Irish heavyweight champion, having won the crown in both 1908 and 1909. Leahy was also one of the Eight that won the Thames Cup at the 1903 Henley Royal Regatta, having been introduced to rowing by Bram Stoker (author of Dracula) while at Trinity College, Dublin. During this time Shields also became engaged to his cousin Dorothy Hornby, the third daughter of Colonel John Hornby, 12th Lancers, and they were due to be married in October 1914.

The Cambridge 1910 Eight, with Shields sitting on the far right.

He became attached to the 1st Battalion Irish Guards and was with them in Caterham when war was declared. He travelled with them to France on 12 August 1914 as part of the 4th (Guards) Brigade of the 2nd Division. The battalion played an important part in the Battle of Mons and the subsequent rearguard actions during the British army’s retreat. They were involved in the actions at Landrecies, and then at Villers-Cotterets on 1 September during the Battle of Le Cateau. During the latter engagement their commanding officer (CO), Lieutenant Colonel the Honourable George Morris, and the second-in-command, Major Hubert Crichton, were killed. It was also during this action that Hugh Shields was taken as a prisoner of war by the Germans after insisting on staying behind to tend the wounded. Interestingly he was captured along with his former boxing rival, Leahy, who was also attached to the Irish Guards. Leahy was badly wounded in the right leg and had to have it amputated. He was eventually repatriated in July 1915 and died in 1965, keeping his interest in rowing to the very end of his life.

The French eventually overran the German camp in which Shields was being held. Shields, together with another RAMC officer, Lieutenant H.C.D. Rankin, managed to escape by stealing a German officer’s horse and riding back to their own lines. Quite an adventure. Shields rejoined his regiment on 12 September 1914. For his actions over this period he was mentioned in Sir John French’s dispatches of 8 October 1914. On 25 October 1914 Shields wrote home to his parents: ‘I must say it was very frightening work running up and down behind the trenches to see men who were wounded, as the bullets were rather thick at times.’

A few days later on 27 October 1914 he was shot and killed while attending a wounded man in the open. Shields was recommended for the Victoria Cross by his brigadier, Lord Cavan, for his behaviour on this day.

His commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Lord Ardee, wrote a moving letter to his parents about his death:

He was killed while attending to a wounded man in the firing line during an attack on Rentel, eight to ten miles east of Ypres … The way in which he insisted on attending to wounded men under fire was the admiration of all of us. On more than one occasion I have advised him not to expose himself so much, but he always would do it, out of a sense of duty. He was shot in the mouth and through the neck while bending down and was killed instantly.

Another wrote:

The battalion were in action in Polygon Wood four and a half miles due east of Ypres. There were two companies in reserve: two in the main line of trenches, and a few outposts (rather a risky job unless in very good cover). Needless to say, the usual place of medical officers is with the reserves, or further back. On this occasion the cover for the outposts was rotten. They were fairly crawling along like caterpillars under rather a bad fire, till one of them was laid out, and lay there in the open thrashing about. Orr-Ewing (Scots Guards), at present commanding us, said at dinner the other night that he was appalled to see Shields strolling out across our trenches (all our men in the trenches with their heads down), and go and fish out some bandages and tie him up. Needless to say, that he was hit before he had been there one moment; the shot hit him in the neck and killed him outright.

The most interesting of the letters comes from Captain the Honourable H. Alexander who wrote:

I think the nicest thing I ever heard was said by one of our men, who said, ‘Mr. Shields is the bravest man I ever saw.’ The officers said he was too brave and told him but he always said he felt it was his duty to help wounded men whenever he could. If anyone has done his duty and a great deal more, he has. He rejoined us again at Soupir. It was here that we went up the Castle together. It was at Soupir where Hugh did such frightfully good work by carrying the wounded, both English and German, out of a burning farm which was being very heavily shelled. We moved from there about 20 Oct to Ypres. Hugh died in front of a place called Roulers; he was attending to a wounded man in the open during an attack not more than 200 yards from the enemy. We are all very sorry, as he was so popular in my regiment, but there is consolation in the thought that he himself would not have wished a better death, and he could not have died more gallantly.

Shields was initially buried in the grounds of Huize Beuckenhrost, Zillebeke. However, over the years his body was lost or destroyed and he is now commemorated on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial, panel 56. His name also appears on the Thornford War Memorial.

An edition of his diaries written between 12 August and 25 October 1914 was later privately printed and can now be seen on the Wellcome Library website.

2

SECOND LIEUTENANT REGINALD WILLIAM FLETCHER

Boat position: Bow

Race: 72nd Boat Race, 28 March 1914

College: Balliol College, Oxford

Served: 118th Battery, 26th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery

Death: 31 October 1914, aged 22

In their death they are not divided: they were swifter than Eagles! They were Stronger than Lions.

Reginald William Fletcher (more commonly known as Reggie) was born on 18 March 1892 at Norham End, Oxford. He was the third son of Charles, a history tutor at Magdalen, and Katharine Fletcher. He was educated at the Dragon School, Oxfordshire, before ill health forced his parents to send him to Mr Pellatt’s at Durnford, Langton Matravers, Dorset, where the climate and fresh air was considered better for his health.

Reginald William Fletcher.

A bright, determined boy, he gained a scholarship to Eton College in 1905, remaining there until 1910. While at Eton he rowed in the Eight and served in the Artillery OTC (Officers’ Training Corps). He went up to Balliol College, Oxford (1910–14), where he obtained a Second in Honour Moderations in 1912 and later a Second-Class BA in 1914. A great one for the classics, he knew quantities of Homer and Aeschylus by heart and was a fine writer of Latin and Greek verse. Although his second-class degree was a good one, he was expected to get a First and the result was a disappointment to both him and his tutors. He once again became a member of the artillery section of the OTC, later becoming second in command of the corps. He was also a keen Freemason. He stroked for the Trial Eight at Oxford in three successive years, 1911, 1912, 1913, and for four years was stroke of his college boats, both Eights and Fours. He also rowed for the Leander Four at Henley Regatta in 1913 and was selected for the Oxford University boat to take part in the 1914 Boat Race.

72nd Boat Race, 28 March 1914

Oxford went into the 72nd Boat Race as reigning champions having beaten Cambridge the previous year, 1913, by ¾ of a length. However, due to problems with their crew order they were not the favourites, despite having five returning racers in their boat. Sidney Swann (Trinity Hall – number two), who was making his fourth appearance for Cambridge, L.E. Ridley (Jesus – cox), C.S. Clark (Pembroke – number six), G.E. Tower (Third Trinity) and C.E.V. Buxton (Third Trinity). The Oxford boat had four crew members with previous Boat Race experience: E. Horsfall (Magdalen – number four), H.K. Ward (New College – number three), E.F.R. Wiggins (New College) and H.B. Wells (Magdalen). Horsfall also won gold medals in the Men’s Eight at the 1912 Olympic Games, rowing for the Leander Club (Horsfall survived the war, having served with the RFC (Royal Flying Corps) and winning an MC (Military Cross) and DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross), before going on to win a silver medal rowing stroke for the Leander Eight during the 1920 Olympic Games. In 1948 he managed the British rowing team.

For the eleventh year in succession the umpire was Frederick Islay Pitman (Third Trinity), the former Cambridge stroke who had raced between 1884 and 1886. The Oxford coaches were: G.C. Bourne (New College) who had raced for Oxford between 1882 and 1883, both Oxford victories; his son Robert Bourne (New College) who had rowed four times for Oxford in 1909 (Cambridge), 1910 (Oxford), 1911 (Oxford) and 1912 (Oxford) and Harcourt Gilbey Gold (Magdalen) who had stroked Oxford to victory in 1896, 1897, 1898, losing in 1899. Gold was made president of the Oxford University Boat Club in 1898. Cambridge were coached by Stanley Bruce who had rowed number two for them in 1904 (Cambridge).

Cambridge won the toss and decided to take the Surrey side, leaving the Middlesex side to Oxford. It was a beautiful day with a light wind and smooth water. The sun shone warmly on both rowers and bystanders as Pitman started the race precisely at 2.20 p.m. Cambridge started strongly and were ¾ of a length ahead by Craven Steps. The rumours of their speed and strength were not exaggerated and by the Mile Post the Cambridge crew had increased their lead to 1¼ lengths. They had increased their lead still further by Hammersmith Bridge, finally winning the race by 4½ lengths ahead, in a time of 20 minutes 23 seconds. It was the first time Cambridge had won the race since 1908, reducing Oxford’s overall lead 39–31.

Cambridge Eight 1914 with Fletcher as bow.

The 1914 race was the last one for six years and they didn’t commence again until 1920, the First World War putting an end to the event for the first time since 1853. Five of the 1914 crew died during the war, four from Cambridge and one from Oxford.

***

Fletcher was gazetted to the 8th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, on the day war was declared, sailing for France on 20 August. He got to the Front during the Battle of the Aisne serving with the 116th Battery. On 21 October he transferred to the 118th Battery, Royal Field Artillery, and was with them when he met his death on 31 October 1914 at Gheluvelt, about 6 miles east of Ypres. It was later learnt that a shell exploded close to him while he was returning from a forward observation post. He was buried where he fell the same evening.

His obituary later said of him:

Regie was never so happy as when he was in lands where the Eagles had never been carried, Iceland, Norway, the far west of Scotland or Ireland. He loved to sleep in the open air, and would sleep quite comfortably under several degrees of frost. As in face and coloring, so in his fierce independence of character, he seemed like some old Norse Rover; and it was this same independence that made one of his schoolmasters compare him to Achilles. In truth the oldest Greece was almost as much a source of inspiration to him as were the Sagas; extraordinarily well-read as he was, for a man of twenty-two, in the best modern literature, his highest delight was in Greek poetry; he knew enormous stretches of Homer and Aeschylus by heart, and would chant them, to the amazement of his crew, in the Balliol barge.

The master of Balliol College wrote:

However, fiercely he might have been growling at the said crew in the afternoon, there was not a room in the College in which he would not have been the most welcome of all guests an hour or two afterwards.

His major wrote shortly after his death:

I have lost a very charming and cheery comrade and a very gallant and capable officer. From a military point of view his death is a great loss to the Battery and from a personal point of view it has been a great shock and grief to his brother officers.

Reginald’s body was never recovered or identified and he is commemorated on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial, panels 5 and 9.

His older brother Walter George Fletcher was killed on 20 March 1915 serving with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. He was also at Eton and Balliol and rowed for both, but not to his younger brother’s standard.

Both brothers are also commemorated in the cloisters at Eton College, Windsor. The inscription on the memorial reads:

REMEMBER WITH THANKSGIVING

TWO BROTHERS BOTH SCHOLARS OF THIS COLLEGE

WALTER GEORGE FLETCHER

CAPTAIN OF THE SCHOOL 1906. ASSISTANT MASTER 1913 – 1914

SECOND LIEUTENANT ROYAL WELCH FUSILIERS.

KILLED AT BOIS GRENIEN MARCH 20TH 1915 AGED 27

REGINALD WILLIAM FLETCHER

SECOND LIEUTENANT ROYAL FIELD ARTILLERY

KILLED AT GHELUVELT OCTOBER 31ST 1914 AGED 22.

He is also commemorated on the Langton Matravers and Durnford School War Memorial.

3

CAPTAIN BERNARD RIDLEY WINTHROP-SMITH

Boat position: Number Six

Race: 62nd Boat Race, 1 April 1905

College: Trinity College, Cambridge

Served: 1st Battalion, Scots Guards

Death: 15 November 1914, aged 31

His body was returned to lie in English soil.

Bernard Ridley Winthrop-Smith was born on 19 December 1882 at Little Eton, Derbyshire. He was the only son of Francis Nicholas Smith and Constance Ella Winthrop (daughter of the late Reverend Benjamin Winthrop of No. 82 Cromwell Road, London) of Wingfield Park, Ambergate, Derbyshire. He was educated at Carters in Farnborough, before moving on to Eton College (Evans House) and then on 25 June 1901 went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, as a pensioner (without a scholarship), where he obtained his degree in 1904 (BA).

Captain B.R. Winthrop-Smith

At 6ft 5in tall, broad and strong, Bernard had rowed successfully in the Eight at Eton and for Trinity College, Cambridge. As a result of his success he was selected to row number six for Cambridge in the 1905 Boat Race.

62nd Boat Race, 1 April 1905

Having won the race in 1904 by 4½ lengths Cambridge went into the 1905 race as reigning champions. However, due to various misfortunes and illness they were not the favourites. The Cambridge coaches were John Edwards-Moss (Third Trinity) who had rowed number seven in 1902 and 1903, Francis Escombe (Trinity Hall) and David Alexander Wauchope (Trinity Hall) who both stroked for Cambridge in 1895. The Oxford coaches were William Fletcher (Christ Church) who had stroked and rowed number six and seven for Oxford between 1890 and 1893; C.K. Philips (New College) who had rowed number three for Oxford during their four victories between 1895 and 1898. Frederick I. Pitman (Third Trinity), who had stroked the Cambridge between 1884 and 1886 was the umpire again for the third year running.

The Cambridge crew had four returning rowers including P.H. Thomas (Third Trinity) who replaced Stanley Bruce (who himself had replaced W.P. Wormald due to illness) at the last minute due to illness. Despite making his fourth appearance in the race, having been in the winning crew during the previous three years, 1902–04, he joined straight from an African expedition. Not the best preparation for such an important race. The other three were H. Sanger (Lady Margaret Boat Club – bow), R.V. Powell (Third Trinity – number seven) and B.C. Johnson (Third Trinity – number three). The Oxford crew contained five rowers with previous experience including A.K. Graham (Balliol – number seven), E.P. Evans (University – number six), A.R. Balfour (University – number four), A.J.S.H. Hales (Corpus Christi – number three) and R.W. Somers-Smith (Merton – bow).

Cambridge University won the toss and chose the Middlesex station, leaving Oxford with the Surrey side. Pitman began the race at 11.30 a.m. Oxford took the lead quickly and by the Mile Post they were in a commanding position. They continued to dominate the race and eventually won by 3 lengths in a time of 20 minutes 35 seconds. It was Oxford’s first victory in four years.

***

Bernard decided on a career in the army. As the nephew of Sir Gerald Smith KCMG, a former lieutenant colonel of the Scots Guards, strings were pulled and he was gazetted into that regiment as a second lieutenant on 1 August 1905, and promoted to lieutenant on 14 May 1910. On 13 August 1913 he was seconded for service under the Colonial Office and appointed aide-de-camp (ADC) to Sir Harry Belfield KCMG, the governor and commander-in-chief of the East African Protectorate (Kenya). At the outbreak of the First World War Bernard managed to get leave from the Colonial Office and rejoined the 1st Battalion, Scots Guards, who formed part of the 1st (Guards) Brigade, British 1st Division, in October 1914, just in time to take part in the First Battle of Ypres (14 October–30 November). On 8 November 1914, whilst his regiment was at the Front near to Ypres, he was given orders to attack and retake a trench on the battalion’s flank that had been occupied by some German troops after it had been vacated by Zouaves (light French light infantry distinctive because of their short open-fronted jackets, baggy [serouel] trousers, sashes and oriental head gear). Attacking over open ground and leading his platoon from the front he was hit and badly wounded by a bullet from a shrapnel shell and sustained a compound fracture to the base of his skull. Carried back to his own lines by his men, he was evacuated a few hours later to the Popering field hospital. Three days later, on 11 November, and in need of better medical attention, he was evacuated to the Christol base hospital in Boulogne. Unfortunately, despite receiving the best medical attention, Bernard’s condition worsened and his parents were sent for. He died without regaining consciousness on 15 November 1914 with his parents by his side. He was promoted to captain on the day of his death. A total of 281 officers and 6,237 other ranks were killed during the First Battle of Ypres. Bernard alas was one of them.

Winthrop-Smith Memorial, South Wingfield Park (Burial Ground), Wingfield Park, Ambergate, Derbyshire.

Colonel A. Clutterbuck in his book Bond of Sacrifice describes Captain Winthrop-Smith as:

an exceptionally fine man, 6’ 5” tall and broad in proportion. He was much liked by the men of the right flank company of the 1st Battalion of the Scots Guards and by his brother officers.

Unusually Bernard’s body was returned to England, travelling back with his parents. He was buried in South Wingfield Park (Burial Ground), Wingfield Park, Ambergate, Derbyshire.

As a lasting memorial to their son, his mother and father paid for a memorial in the form of a stained-glass window at St Matthew’s, the parish church of Pentrich. The window at St Matthew’s was by Christopher Whitworth Whall (1849–1924). The inscription below the window reads:

To the Glory of God and in loving memory of our son Bernard Winthrop-Smith, Captain, 1st Scots Guards, died of wounds received at Ypres, Belgium, Nov.15.1914.

He is also commemorated on the war memorial in the cemetery at Wingfield Park, the Eton College War Memorial and Cambridge’s Trinity College Chapel.

Cambridge 1905 Eight. Standing from left to right: E. Wedd, R. Winthrop-Smith, G. Cochrane, W. Savory, unknown. Middle row: P. Thomas, H. Sanger, C. Taylor, B. Johnstone, P. Powell. Front row sitting: R. Allcard.

4

SECOND LIEUTENANT CYRIL FRANCIS BURNAND

Boat position: Number Four

Race: 68th Boat Race, 1 April 1911

College: Trinity College, Cambridge

Served: 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards

Death: 11 March 1915, aged 23

He was the only Catholic officer in the 1st Grenadiers, and was always of the greatest help to me in my ministrations.

Cyril Francis Burnand was born on 31 July 1891 at No. 1 Cavendish Square, London, the only son of Mr and Mrs Charles Burnand, of the same address, and the grandson of Sir F.C. Burnand, for many years the editor of Punch. He attended Mr Roper’s School at Bournemouth in 1900, before going to Downside (Roman Catholic) School, Bath, in April 1904. At Downside he was described as a ‘bright young boy’ who always took a keen interest in participating in school activities. He was in the second XI in football and hockey (1908–09), being so enthusiastic that he snapped a tendon in 1907. He also won the School Challenge Cup for swimming four years in succession (1905–08). In 1909 he passed the Higher Certificate. He sang in the choir and was keen in all musical activities. He was a gifted actor and played Butterman to much acclaim in the Downside staging of Our Boys and later Benjamin Goldfinch in A Pair of Spectacles.

Second Lieutenant Cyril Francis Burnand, Grenadier Guards.

After Downside he was admitted as a pensioner (a student without any form of scholarship) to Trinity College, Cambridge, on 25 June 1909. He was elected to the Trinity Boat Club and rowed at Henley. Much to the delight of the Fisher Society (the body that runs events each week during term for all Catholic undergraduates and graduates resident in Cambridge), he was selected to take part in the Boat Race in 1911 rowing number four.

68th Boat Race, 1 April 1911

The 1 April was a beautiful day with a light easterly wind and a strong spring tide. The Oxford crew were coached by the former Oxford rower H.R. Barker (Christ Church), who had turned out for the Dark Blues, rowing number seven in 1908 and number two in 1909; the legendary G.C. Bourne (New College), who had rowed bow for Oxford in 1882 and 1883; and the equally famous and four-time Dark Blue (1896–99 rowing stroke on all four occasions) Harcourt Gilbey Gold (Magdalen). Stanley Bruce (Trinity Hall), who had rowed number two during the 1904 race, coached the Cambridge crew, together with William Dudley Ward (Third Trinity), who had rowed number seven between 1897 and 1900; Raymond Etherington-Smith (First Trinity), who rowed number six for Cambridge in 1898 and five in 1900 (Cambridge); and finally, and more unusually, H.W. Willis, the man who had coached Oxford in 1907. The familiar face of the former Cambridge stroke (1884–86) Frederick I. Pitman (Third Trinity) umpired for the eighth year in succession.

Six members of the Cambridge crew had raced before: R.W.M. Arbuthnot (Third Trinity – stroke), J.B. Rosher (First Trinity – number six), F.E. Hellyer (First Trinity – number three) C.R. le Blanc-Smith (Third Trinity – number five), C.A. Skinner (Jesus – cox) and G.E. Fairbairn (Jesus – number seven). Two members of the Cambridge crew came from South Africa, Pieter Voltelyn Graham van der Byl (Pembroke – number two) and C.A. Skinner (Jesus – cox). Six members of the Oxford crew were students at Magdalen College and had won the Grand Challenge Cup at Henley the year before. Three of the Oxford crew had also taken part in the race twice before, Duncan Mackinnon (Magdalen – number seven, 1909–10), Robert Bourne (New College – stroke, 1909–10) and Stanley Garton (Magdalen – number six, 1909–10). Charles Littlejohn (New College – number five) came from Australia.

The 1911 race was made all the more interesting for several reasons. Firstly because it was followed by the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII) and his brother Prince Albert. It was also the first race ever to be monitored by an aeroplane. This never-before-seen sight was later reported on by the Western Argus, 9 May 1911:

THE BOAT RACE BY AEROPLANE

SIX AIRMEN OVER THE COURSE

Six aeroplanes flew over the course of the Boat Race between Oxford and Cambridge, and one airman followed the race almost from start to finish, sweeping to and fro across the river to keep level with the crews. The machines were welcomed with great enthusiasm by the crowds. The airmen were Graham Gilmour (who followed the race), who came from Brooklands in a Bristol biplane with a Gnome engine, and five others who came from Hendon aerodrome. Graham White (military Farman machine), Mr Hubert (Ordinary Farman), Gustave Hamel, Mr Greswell and M. Prier all used Bleriot monoplanes. Mr Gilmour later recounted his experience:

I left Brooklands at 1.55pm in a military-type Bristol biplane and followed the river until I reached Putney Bridge. I arrived at the start just before the pistol was fired. Overhead as I circled around was a balloon in which was the Hon Mrs. Atsheton Harbord … As soon as the boats started off I followed them up the river. More than once I turned of my engine and descended as low as 100 feet above the water, but my normal altitude during the flight was about 200 feet. The spectacle below me was most interesting. I could see the crews quite distinctly. From my aerial point of view they had rather the appearance of flies skimming over a pond in the summer. I could distinguish perfectly well between the two crews by the colors of their oars and it was quite apparent to me from above that Oxford was the better crew of the two. Indeed criticizing the race from an aerial standpoint the first time that such a view had been obtained I could see that Cambridge had a hopeless task, because every time Oxford was pressed the crew responded at once and the boat forged ahead … After flying over the winning post I landed in a little field (Chiswick Polytechnic cricket field) having run out of petrol. A motorist very kindly gave me four gallons from his supply and I again filled up my tank.

A member of the crowd then helped him start his plane up and he flew the 18 miles back to Brooklands for tea. Alas, Gilmour was killed the following year while flying over the Old Deer Park in Richmond. Gilmour had set off from Brooklands at about 11 a.m. to make a trial cross-country flight in a Martin Handasyde monoplane. Flying at about 400ft, his left wing suddenly folded and he crashed to the ground and was killed on impact.

Cambridge Eight, 1911 Boat Race.

Oxford won the toss and selected the Middlesex side while Cambridge was handed the Surrey side. The race started at 2.36 p.m.

Oxford made a quick start with Bourne, the Oxford stroke, outrating Cambridge by 2 strokes per minute. By the Craven Steps Oxford were ¾ of a length ahead – a lead they maintained past the Mile Post. Oxford had increased their lead by the Crab Tree pub and were even further ahead by Harrods Furniture Depository. As they passed under Hammersmith Bridge, Oxford were 2½ lengths ahead and still pulling away from Cambridge. By Chiswick Steps Oxford had a 4-length lead, which they had increased by Barnes Bridge. Although the Cambridge crew rallied there was no catching Oxford and they won by 2¾ lengths in an all-time race record time of 18 minutes 29 seconds. It was Oxford’s third consecutive victory making the overall tally 37–30 in Oxford’s favour.

Guy Nicholls later writing about Burnand in the Morning Post reported, ‘Burnand rowed in better style than anyone in either crew.’

***

After obtaining his BA degree in 1912 Burnand left Trinity and joined the Midland Railway Company. He had always had a keen interest in railway engineering, and secured a position as a porter with the intention of making the railway his career. Moving to Nottingham to pursue his career, he became a member of the Nottingham Rowing Club. However at the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, he left the company and joined the Special Reserve of Officers, being gazetted into the 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards, as second lieutenant. He went to France with his battalion on 17 December 1914. At the end of February he was granted a short leave home before returning to his battalion in March 1915. A week later on 11 March 1915 he was killed in action during the fighting at Neuve Chapelle. Between 10 and 13 March 1915 the Indian Army Corps together with IV Corps (which the 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards were a part of) attacked the village of Neuve Chapelle in an attempt to break through the German lines. The attack commenced at 7.30 a.m. on 10 March with a massive bombardment, which was intended to destroy the enemies wire and front-line trenches. The bombardment lasted for 30 minutes, after which at 8.05 a.m. the infantry moved forward. After hard fighting Neuve-Chapelle and over 1 mile of German front-line trenches were captured. However, due to poor communications, they let the Germans reorganise and reinforce, resulting in the British attack being brought to a halt. The 11 March was a dull and misty day, which caused problems for the artillery trying to spot their targets. At 7 a.m. the infantry moved forward, however, with little damage having been caused to the German positions. Moreover, with those that had been hit repaired, the infantry ran into a storm of machine-gun and artillery fire. The offensive finally petered out on 13 March with the British having suffered over 12,000 casualties. Unfortunately Second Lieutenant Cyril Francis Burnand was one of the casualties. A letter from a brother officer later explained:

… the Guards carried out their orders and Cyril had done remarkably well, but in leading his men on to the parapet of the trenches he was shot in the stomach and died almost immediately. He fell into the arms of another officer, but unfortunately he, poor fellow, was killed the next day …

Father Reginald Watt, Catholic chaplain with the 23rd Field Ambulance of the 7th Division, wrote to Cyril’s father:

It is with the sincerest personal regret that I consider your son’s death. As doubtless you have already been informed, he died gallantly at the head of his men in battle yesterday. He was the only Catholic officer in the 1st Grenadiers, and was always of the greatest help to me in my ministrations; to the Catholics of his regiment, and still more to me, his loss is a great disaster. I intend to say Mass for him to-morrow. God bless you and help you in this great grief.

Cyril’s manager at the Midland Railway later wrote to his parents:

Dear Mr. Burnand, I feel that I must write at once to tell you how much I feel for you and Mrs. Burnand in the terrible sorrow that has come to you.

I think perhaps in some ways, I can feel for you more deeply than many of your more intimate friends, for I had watched and tried your boy very carefully, and had come to the conclusion that he was quite the best young man that had ever come to me in the Midland. I miss him very often and very much. He had most unusual gifts for a young man, great force of character, adaptability, capacity for dealing with men both above and below him … the Midland will be very much the poorer for his loss. I never met a younger man in whom I had greater confidence.

Cyril Burnand’s body was never discovered or identified and he is commemorated on the Le Touret Memorial, panel 2. He is also remembered on the Nottingham Rowing Club Memorial and his parents presented a brass memorial plaque to Downside Abbey Church. It can still be seen there today.