Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

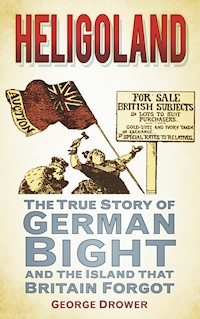

In 1956 sea area Heligoland became German Bight. But why did the North Sea island, which for nearly a century had demonstrated its loyalty to Britain, lose its identity? How had this once peaceful haven become, as Admiral Jacky Fisher exclaimed 'a dagger pointed at England's heart'? Behind the renaming of Heligoland lies a catalogue of deceit, political ambition, blunder and daring. Heligoland came under British rule in the nineteenth century, a 'Gibraltar' of the North Sea. Then, in 1890, despite the islanders' wishes, Lord Salisbury announced his intention to swap it for Germany's presence in Zanzibar. The Prime Minister's decision unleashed a storm of controversy. Queen Victoria telegrammed from Balmoral to register her fury. During both world wars, it was used by Germany to control the North Sea, and RAF planes bombed the once-British territory. The story of Heligoland is more than an obscure footnote to the British Empire - it shows the significance of territory throughout history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 442

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Heligoland is just 290 miles from Britain’s Norfolk coast.

GEORGE DROWER

First published in 2002

This edition published in 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© George Drower, 2002, 2011

The right of George Drower, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7280 5

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7279 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Introduction

1.

HMS

Explosion

Arrives

2.

Gibraltar of the North Sea

3.

Rivalries in Africa

4.

Queen Victoria Opposes

5.

Swapped

6.

The Riddle of the Sands

7.

Churchill Prepares to Invade

8.

Project Hummerschere

9.

‘Big Bang’

10.

The Islanders Return

11.

Forgotten Island

Notes

Bibliography

(Harrison, Pastures New, 1954)

Introduction

‘There are warnings of gales in Viking, North Utsire, South Utsire, Forties, Dogger, Fisher . . .’. Those sea area reports, which are read out on the UK’s Radio 4’s Shipping Forecast, all have their own recognisable personalities and quintessentially British-sounding names. A curious exception is the one called ‘German Bight’. It is a wild 20,000-square-mile area of sea and coast which stretches between two headlands: near the Dutch island of Texel, to the Jutland port of Esbjerg. For many centuries seafarers knew this tempestuous corner of the North Sea as the ‘Heligoland Bight’. That was until 1956 when, in the absence of any British government objections, the Meteorological Office agreed for it to be renamed. For secretive reasons it was not Germany which preferred to keep Heligoland Bight airbrushed out of its history, and with it the remarkable story of the forgotten island at its heart – from which the Bight’s true name derives.

Then on 18 August 1965 a file marked ‘Secret’ landed on the desk of the Foreign Secretary, Michael Stewart. At that time Britain was having to protect the inhabitants of Gibraltar against an economic siege by Spain, which was demanding sovereignty of the Rock. Yet the Foreign Office was willing to become more radical in its steps to cope with such ‘End of Empire’ dilemmas. In 1968 it contemplated handing over the Falkland Islands to Argentina. Secretly, in order for Britain to conduct H-bomb tests, it had arranged for the eviction of the coconut gatherers from Christmas Island in 1957, and in 1966 was considering deporting the inhabitants of Diego Garcia from their homeland, to lend it to the United States to develop into a military base.

Stewart was intrigued to see that this report concerned none of those. It was from the British Ambassador to Germany, Sir Frank Roberts, who had just attended a 75th anniversary celebration in a North Sea island which even the Foreign Secretary had never heard of. The ambassador, who had been astounded by the good-natured welcome he had received in this former British colony, reported that: ‘Everywhere I heard comments from the Islanders on the tradition of the benevolence of the British Governors.’

In August 1890, when it was still an enchantingly obscure British possession, Heligoland had become the focus of international attention as the hapless bait in an astonishingly epic imperial deal to persuade Kaiser Wilhelm II’s Germany to hand over substantial elements of the continent of Africa. In Britain the audacious, and quite unprecedented, territorial swap provoked public protests that Summer. Even Queen Victoria furiously remonstrated that the two thousand inhabitants of this sophisticated island were being callously sacrificed like pawns in a diplomatic chess game.

Unforseeably, the story of Britain’s involvement with Heligoland continued after the transfer of sovereignty in 1890. There was cause bitterly to lament Lord Salisbury’s decision to yield it in both world wars, when the strategically vital island was turned against Britain. It was becoming, as Admiral of the Fleet ‘Jacky’ Fisher, exclaimed, ‘a dagger pointed at England’s heart’. In its waters was fought the Battle of Heligoland Bight, the first surface scrimmage of the First World War; and next, the Cuxhaven Raid, the first British seaplane incursion. Started on the island was ‘Project Hummerschere’, an ambitious scheme in the interwar years to construct a German form of Scapa Flow – so important that it was visited by Hitler in 1938. During the Second World War there came to be further significant historic records: for example, in 1940 the RAF’s first mass night bombing raid of that conflict was made over the Bight.

And then, unbeknown to many, Britain next inflicted on Heligoland a misdeed far worse than a mere swap. Between 1945 and 1952 the Heligolanders were exiled to mainland Germany while the British – probably illegally – used the island as a bombing range for high-explosive and chemical weapons, and evidently as a test-site for various elements of Britain’s prototype atomic bomb. Even now the quaint mile-long island still bears the scars, albeit now hidden by lush vegetation. Such was the severity of the bomb damage suffered in April 1945, when the 140-acre former British colony was attacked by the RAF with a thousand-bomber raid, that the windswept upper plateau remains buckled and twisted like the cratered flight deck of a crippled aircraft carrier. Despite such devastation, there remain a few indelible clues to its British colonial past: a street named after an English governor, and a church wall bearing a shrapnel-scarred bronze tablet honouring Queen Victoria.

For all its commercial sophistication, Heligoland is a beguiling place, guided predominantly by the rhythms of the seasons. Its people are a tough, independently minded, close-knit community of seafaring folk: strong, stoic, quiet and slow-moving. Their first loyalty is to their island and their outlook so innately maritime that they instinctively keep their sturdy houses and tiny gardens neat and shipshape. On the walls of their hotels, guest houses and even private houses hang maritime pictures – sometimes of old British merchant ships. Traditionally, despite Heligoland’s constitutional links to the states of Denmark, Britain and then Germany, they have continuously sustained a deep perception of themselves and their island as a distinct and viable entity. Not untypically for inhabitants of small islands, their downfall has been their reluctance to sustain an effective representation of themselves in influential political arenas abroad until it is too late.

Known to the Germans as ‘Helgoland’, for simple linguistic reasons, the island lies tantalisingly close to Germany’s North Sea coast. Even so, the severity of the weather in the Heligoland Bight means tourist ferries mostly only dare to make the 30-mile dash during the summer months. German trippers willing to brave the often stormy trip arrive from Hamburg and the coastal ports of the coasts of Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein. By late morning the graceful white ferries have converged on the roadstead, where they ride at anchor until the late afternoon; then, fearful of being caught in the Bight after dark, they wisely scurry off home. To visitors, the island seems to represent an earlier, more innocent world, and one which has no need for cars or even bicycles. Goods are moved on four-wheeled hand-trolleys, rather like miniature corn wagons. Each year tens of thousands of tourists are drawn to the island, some of them attracted by its defiantly anachronistic allure as one of Western Europe’s last outposts of duty-free shopping. Some trippers go for the chance of a few hours’ bathing on the nearby dependency, Sandy Island, and a few for the exceptionally clear sea air, which is claimed to be the secret of the islanders’ remarkably healthy old age.

Heligoland became a British colony in 1807, and from the very outset it was strategically important because of its location in the corner of the North Sea near the estuary of the Elbe and three other great rivers. During the Napoleonic wars the island played a crucial role as a forward base for the officially endorsed smuggling of contraband to the continent, and also as a centre for intelligence gathering. After the wars it established itself as a tourist resort, on the initiative of an entrepreneurial islander, and settled down to life as a British colony. For Britain, a major world power with more island colonies scattered across the globe than it knew what to do with, Heligoland was not unique. But for neighbouring Germany, it was very much a novelty. Artists, poets and nationalists venerated Heligoland, all too often – to the bemusement of the islanders – devising ludicrous fantasies that it embodied the essence of the Germanic spirit. In 1841 Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben wrote Germany’s (old) national anthem there (while it was still under British rule!) Few were more enchanted with the romance of the place than Kaiser Wilhelm II; some years before he was crowned, he visited the island and vowed to make it German. Bismarck, his Chancellor, regarded Heligoland in terms of its strategic disadvantages as a British outpost, and coveted it for many years, not least to provide security for his pet project, the Kiel Canal. Indeed, he even suggested to Prime Minister William Gladstone that the island might be exchanged for an enclave in India called Pondicherry. This was refused.

But in August 1890 Lord Salisbury (who was both Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary) prepared to hand over this enchanting island to Germany in order to halt further German encroachments into East Africa, thereby preventing the ruthless German colonialist Dr Karl Peters – himself born near Heligoland – from gaining control of the headwaters of the Nile. This astonishingly audacious deal – concerning which the islanders’ opinions were never sought – included Zanzibar and various border areas in East Africa. Salisbury certainly did not get everything his own way. His fiercest critic was no less a personage than Queen Victoria, who in private furiously condemned Salisbury for even considering handing over the island. Several British newspapers and cartoonists were nearly as scathing in their criticism.

One cause of the interest in the island was its actual physical composition. The power of the waves in the Bight was such that Heligoland (and Sandy Island) was perpetually changing its shape. Coastal erosion was ongoing: sometimes barely perceptibly, but occasionally, especially in winter, dramatically, as prized sections of the cliffs disappeared overnight. And yet somehow Heligoland retained a magical quality of indestructibility. No matter what Nature (or Allied bombers) could hurl at it, the island would always survive. For decades none of this has ever needed to be known to British travellers because few, if any, caught even the most distant glimpse of the island. Passengers on civilian airliners never see Heligoland through the portholes because all the aircraft that shuttle between England and the main northern German cities – Bremen, Hanover, Hamburg and Berlin – cross the North Sea coast over the Netherlands. And even the car ferries operating between Harwich and nearby Cuxhaven often sail past the island at night.

In view of the number of significant events and personages with which it has been associated, it is astonishing that Heligoland has remained so undiscovered. It is only 290 miles from Great Yarmouth, yet very few people in Britain even know of its existence at the centre of the stormy Bight. Each year, on 9 August, the islanders gather at their town hall, the Nordseehalle, for a dignified public commemoration of the 1890 cession. But no British person ever attends it. By an extraordinary series of oversights, Heligoland has repeatedly missed out on opportunities to make the headlines in Britain. It broke a remarkable assortment of historical records: in addition to having the quaint distinction of being Britain’s smallest colonial possession, Heligoland was also Britain’s only colony in northern Europe. The first sea battle of the First World War was fought in its waters, while in the Second World War it was reputed to have been the first piece of German territory upon which RAF bombs fell. Then, in the postwar era, it secretly figured in Britain’s atomic bomb programme.

So often it slipped through the net. In Victorian times its people were seldom invited to colonial gatherings, and later, when the British Commonwealth began to take shape in the 1920s, it did not participate in that either because it no longer had any constitutional links with Britain. Both the 25th and the 50th anniversaries of its transfer into German hands coincided with more dramatic events in the First and Second World Wars respectively, and so the occasions passed unnoticed in Britain. Several interesting consequences have flowed from this lack of wider British knowledge of Heligoland. Almost invariably it has allowed Whitehall a freer hand, almost always at the expense of the interests of the island. For the public, having ceased to be reminded of it, Heligoland vanished beyond the horizon of consciousness. Soon the only readily perceivable lost worlds were fictional places in movies like: Mysterious Island (1961), Creatures the World Forgot (1971), The Island at the Top of the World (1974), and The People That Time Forgot (1977).

Government secrecy has certainly played a part in the island’s history. At first it was as a matter of traditional diplomatic practice that details of the 1807 accession treaty were not publicly disclosed until 1890. More recently there are grounds for wondering whether official attempts have been made to brush aside embarrassing details of Britain’s treatment of Heligoland. Dusty ledgers at the Public Record Office at Kew clearly show in fine copperplate handwriting that several confidential documents concerning the attitudes of the islanders to the swap deal have been destroyed. However, the Heligolanders have clear memories of the misdemeanours committed against their island. This is their story of the enchanting island that Britain knew as the ‘Gibraltar of the North Sea’.

1

HMS Explosion Arrives

Some 30 miles from the coasts of Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony, Heligoland rises like a fist from the swirling waters of the North Sea. Its cliffs tower some 200 feet above sea level, their red sandstone vivid against the cold flatness. Nearby are Germany’s East Frisian Islands (Borkum, Memmert, Juist, Norderney, Baltrum, Langeoog, Spiekeroog and Wangerooge), separated from the mainland by mud and sand flats. Strung parallel to the Lower Saxony coast, this chain of low-lying islands once formed an offshore bar stretching from Calais to the Elbe. Between the coastal islets stretch the muddy estuaries of the rivers Elbe, Ems, Weser and Eider. In this area, known as the Heligoland Bight, strong currents, high winds blowing down from the Arctic and relatively shallow waters combine to produce not only severe weather but also steep waves. Historically, in some winters the rivers would freeze over, and with the thaw large sheets of ice would tear free and flow downstream to the open sea. Even in medieval times such dangerous waters required daring and specialist piloting skills that very few locals other than the Heligolanders were perceived to possess. Centuries later those exceptionally grim sea conditions were vividly brought to the attention of British mariners in the spy novel The Riddle of the Sands by the famous adventure writer and yachtsman Erskine Childers.

By the late summer of 1807, during the Napoleonic wars, England’s situation had become more dangerously isolated than ever. On land, Bonaparte’s armies were sweeping across Europe, relentlessly shattering the powerful coalition the British Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, had constructed just two years earlier with Austria, Russia and Sweden. Austria was defeated at Austerlitz in 1805, Prussia partly broken at Jena in 1806, and the Russians overcome in East Prussia in July 1807. Under the terms of the momentous Treaty of Tilsit in July 1807, Napoleon demanded that Russia become an ally of France; its territories were much reduced and some occupied by French troops, as was what remained of the Lower Saxony part of Prussia. So swiftly did Napoleon’s forces ride into Lower Saxony later that month that Sir Edward Thornton, Britain’s plenipotentiary in Hamburg (effectively its ambassador) had to flee overland to Kiel, narrowly escaping capture. When, soon afterwards, French troops occupied Portugal and then Spain, Napoleon assumed that in some form or other he had secured control of the entire coastline of mainland Europe from the Adriatic to the Baltic.

So far, of all the forces ranged against Napoleon, only the Royal Navy had succeeded in making any significant strategic impact. The attacks on French shipping off Egypt at the Battle of the Nile in 1798 and on the Danish fleet at the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801 proved that Britain was able to make audaciously devastating strikes by sea. Forced by the destruction of the French and Spanish fleets at the Battle of Trafalgar in October 1805 to cancel his long-planned invasion of England, Napoleon decided to bide his time and rebuild his navy. In the meantime he devised an equally ambitious scheme that was intended to subjugate Britain by economic means. In November 1806 he decreed that the so-called ‘continental system’ was to be imposed along the entire coastline of Europe; this was intended to stop any of France’s enemies, as well as neutral countries, from trading with Britain. By placing Britain under blockade, he hoped to ruin the international trade that formed the bedrock of her prosperity, and thus force her to accept his terms for peace. In January 1807 the British government retaliated by declaring a counter-blockade, by which Royal Navy warships would prevent vessels of any neutral country having commercial dealings with any French port, or with any port belonging to the allies of the French.

The stop and search duties this required British warships to undertake were, in certain significant respects, similar to other functions at which they were accomplished. Although such ships could often be subordinate in design to French ships, their signalling systems were more efficient and their discipline superior, making them formidable opponents in action.1 The skills involved in maintaining a maritime embargo they had perfected during the long years of blockading France’s invasion fleet, most notably in the unforgiving seas off Brest and Boulogne. Nevertheless the additional burden of having to impose a counter-blockade against the entire continent greatly stretched the navy’s resources. But Admiral Thomas Russell was determined to keep the might of his squadron concentrated on its job of blockading what remained of the Dutch fleet, sheltering near the island of Texel, and since March 1807 the only vessel he could spare to take station off the mouth of the Elbe was a solitary frigate.

The work was dangerous, but it had to be done. Such were the risks of sailing in bad weather so close to shore (which was unlit at night), the spectre of shipwreck was ever-present. Indeed, of the navy’s total loss of 317 ships in the years 1803–15, 223 were either wrecked or foundered, the great majority on account of hostile natural elements. Notwithstanding the sea-keeping qualities of the Royal Navy’s ships, their capacity for endurance was far from endless. Such was the merciless pounding of the seas on hulls, rigging and spars, Admiral Russell knew that scarcely a month would go by when he did not have to send one or more of his vessels to the safety of the home dockyards for repairs.

The royal dockyards had just about been able to cope with these casualties because as well as building new ships they also had the capacity to repair damaged vessels. From the Baltic they received virtually all the high-quality basic products required, such as timber, flax, hemp, tallow, pitch, tar, linseed, iron ore and other necessities.2 But all that was suddenly thrown into jeopardy in the summer of 1807 when Sir Edward Thornton sent reports to London indicating that France was planning to seize Denmark’s fleet. As a neutral country, Denmark was in an invidious position between the warring factions. As a significant naval power, whose fleet had been rebuilt since 1801, she was regarded as a potential prize by both sides. On 21 July 1807, hearing – possibly via Talleyrand – that Napoleon and Alexander I of Russia were in the process of forming a maritime league against Britain in which Denmark would play a part, the War Minister Lord Castlereagh issued demands for the surrender of the Danish fleet.

Having battled around the Skagerrak in atrocious seas only to encounter frustrating calms in the Kattegat, Admiral Gambier’s task force of twenty-one ships-of-the-line, carrying nearly 20,000 troops, eventually arrived off Copenhagen on 2 September. When the Danish government rejected calls for surrender, a heavy naval bombardment of the city began. The most fearsome weapons used by the British, to devastating effect, were bomb-vessels equipped with huge mortars that lobbed 10-inch diameter fragmentation shells. These burst on contact and cut down personnel indiscriminately. By 5 September some two thousand of Copenhagen’s inhabitants had been killed, many more were wounded and, to bitter parliamentary criticism, the remains of the Danish fleet was seized and brought into the Yarmouth Roads. This brutal pre-emptive strike had been a flagrant breach of Denmark’s neutrality, and it threatened to be politically disastrous. Soon the key states under French influence – Russia, Prussia and Austria – declared war on Britain.3 Significantly, on 17 August Denmark abandoned its neutrality and also declared war on Britain. The British had already been taking stock of Denmark’s possessions, wondering which might be strategically useful, and Denmark’s new stance soon focused British attention on Heligoland.

The fact that Britain had never before needed to fight a war in Europe on such a scale meant that a weakness now appeared in its campaigning. Numerous hitherto obscure parts of Europe were now suddenly of tremendous strategic value – but Britain had little or no intelligence about them. Rather astonishingly, although Heligoland was only some 290 miles from the Norfolk coast, scarcely anyone in Britain knew anything about the island, or even what it looked like. It seems quite probable that the only detailed chart of it the Admiralty had in its possession was a copy of one which had been made for the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce in 1787. This chart had recently been received from the second-in-command of Admiral Russell’s flagship, HMS Majestic, Lieutenant Corbet D’Auvergne; he had acquired it from one Captain Dunbar, who happened to purchase it over the counter of a commercial ship’s chandler during a visit to Copenhagen in 1806.4 Fortunately for Admiral Russell, Lieutenant D’Auvergne was not just an exceptionally enterprising officer. He happened to be the younger brother of Rear-Admiral Philip D’Auvergne, otherwise known as the Duke of Bouillon, who was at that time controlling a network of spies gathering intelligence for Britain via the Channel Islands. The Jersey-based Bouillons were Belgian aristocrats who well knew the frailty of small national entities, having fled to England as long ago as 1672 when they were deposed from their homeland by the French.

The scarcity of detailed knowledge about the south-east part of the North Sea was slightly more surprising because Britain had – albeit intermittently and fleetingly – made various contacts with Heligoland over many centuries. There is a possibility that the island even received its name from a seventh-century English missionary called St Willibrod. The first written reference to the island appeared in ad 98, when it was recorded under the name ‘Hyrtha’ by the Roman historian Tacitus. At the very end of the seventh century, after Willibrod’s accidental arrival there after a shipwreck in about ad 699, it acquired the name Heligoland (meaning ‘Holy Land’), possibly because Willibrod himself came from Lindisfarne, on Northumberland’s Holy Island, or perhaps because it had been a sacred place of the old Norse heathen gods.

Although for innumerable years thereafter various Viking chiefs vied for sovereignty of the island, such a hold as they were able to achieve was often precarious and disinterested. As a consequence there were often lengthy phases when the Heligolanders were left alone, and so virtually governed themselves. In a sense King Canute the Great of Denmark increased the island’s constitutional promiscuity. By virtue of his becoming King of England in 1017, Heligoland came within the ambit of the English Crown for the period of his reign, which ended in 1036. In so far as there were subsequent links they were occasional, almost entirely of a commercial nature, and took the form of trips made by small merchant ships between the island and London’s Billingsgate Market. In Britain it was only such traders who knew of the existence of Heligoland, together with a few mariners who had sought shelter there in bad weather or had perhaps transhipped some cargo in its waters. This remained the situation for centuries. In 1553 Richard Chancellor, the pilot-general of the exploration vessel Bonaventure, en route via Russia to search for a north-east passage to India, noted its existence in his journal – but he only happened to catch sight of it from a distance when his ship was blown off course by a storm. In Napoleonic times there was great need for a wider knowledge of Heligoland but no one had ever bothered to write down – in any language – any sort of history or pilotage notes.

Another beguiling feature of Heligoland’s capriciousness was its ever-changing geographical appearance. By Napoleonic times it had changed dramatically from just a few centuries earlier. About the year 800 it had become home to a civilisation as advanced as any in northern Europe, with several villages scattered over the island. Then covering some 24 sq. miles, it was wooded and fairly low-lying. In the south-west corner there was a huge mound, above which there towered two adjoining promontories, one of red stone and the other of white. Radiating outwards from the centre of the island were ten rivers. At the sources of the northernmost of those rivers were temples that had earlier been used for worshipping Tosla, Mars, Jupiter and Venus; in the south could be found a monastery and five churches. In inlets around the coastline were six anchorages, the three most important of which were on the leeward side of the island protected by three castles. But according to a map of Heligoland produced by the cartographer Johannes Mejerg in 1649, the gnawing away of the coastline by wave erosion and storms had been so voracious that by the year 1300 the sea had devoured all but 4 square miles of the hilly south-west corner of the island. All that remained at its fringes were the monastery, a church and the castle. By 1649 these too had vanished, leaving just an ‘H’-shaped island, half red and half white, from which extended sandy reefs shaped like giant lobster claws.5 And thus it stood until New Year’s Eve 1720. That night there was an epic storm, and the sea surged through, permanently severing the narrow gypsum isthmus that had hitherto joined the western and eastern rocks. From then on Heligoland consisted of two distinct geographical sections, the main part of which was sometimes called Rock Island. Its low-lying dependency, just a few hundred yards to the east, was termed Sandy Island.

The final element in Heligoland’s air of capriciousness was derived from the indefinability of its sovereignty. In 1714 Heligoland notionally became a possession of the Dukes of Schleswig-Holstein, who were Kings of Denmark. Danish rule was fairly remote and the Heligolanders were allowed the freedom to govern their own island as they thought best. Indeed in practical terms the ties that bound Heligoland, Denmark and Schleswig were slight. The island became a de facto No-Man’s-Land, free to all, and afforded a welcome refuge for the people of other islands who were hounded by Danish tax-gatherers. The people made what they could by privateering, fishing and pilotage. Yet in Britain nothing was even known of the form of government which existed on the island. By Napoleonic times the Danish government had granted to Heligoland a few public works such as, in 1802, a fine cliff-side oak staircase joining the Lower and Upper Towns.6

Map 1 Once a large North Sea island: sea erosion meant Heligoland’s land area in 1649 was reduced to a fraction of what it had been. The small southwestern corner was all that remained. (Helgoland Regierung)

Thus, in early September 1807, when Lord Castlereagh was poised to order the seizure of the island, all he had to go on was Lieutenant D’Auvergne’s chart of the waters around it. The whole map measured just 15 inches by 9, less than 3 square inches of which covered the main island. It showed a blur of houses, but crucially gave no indication of where any fortifications might be. This all left disturbing questions about how much conditions there might have altered since 1787 when the chart had been drawn. For example, had the lobster-shaped reefs around Heligoland moved? There were military questions too. How many guns was it armed with? How many troops was it garrisoned by, and how spirited a fight might they make in defending it? So far the only written information available to Castlereagh was Chancellor’s reported sighting of the island as long ago as 1553! But, by extreme good fortune, the person best able to provide the sort of answers Castlereagh needed had just arrived in London.

Even by the standards of the best and brightest of the Foreign Office in that era, Sir Edward Thornton was an exceptionally talented diplomat. The son of a Yorkshire innkeeper, and later a tutor to the household of the Foreign Secretary, Thornton had distinguished himself in the United States as the British chargé d’affaires in Washington. Since 1805 he had been Britain’s plenipotentiary to Hamburg and the Hanse towns, but through his enthusiasm for his duties he had extended his understanding of potentially significant places beyond Lower Saxony. In the process he had made it his business to learn about nearby Heligoland, even though it was a Danish possession. It was in that regard that by 20 July 1807 he was corresponding with the picket ship HMS Quebec, stationed by Admiral Russell in the Bight. On 14 August 1807, having made a dangerous overland journey from Kiel to the mouth of the Elbe, Thornton and three of his diplomatic officials escaped in a small boat into the Bight where they encountered the Quebec. As they clambered aboard, Thornton and his party were greeted by the frigate’s captain, Viscount Falkland. Allowed to remain as guests, they could see for themselves how the warship struggled in those waters to go about her business of intercepting suspicious-looking merchant ships. The potentially immense strategic importance of Heligoland suddenly became apparent on 19 August when news was received from a passing ship that Denmark had declared war on Britain two days before.

By lunchtime on 19 August the seas were sufficiently settled for Thornton’s party to transfer to the brig HMS Constant, which two days later landed them in England.7 Arriving in London, Thornton was invited to a hastily convened meeting with the new Foreign Secretary, George Canning, with whom he discussed what he knew about the situation on the island. Heligoland’s future hung in the balance. Despite the fact that Britain was now at war with Denmark, Canning was reluctant to order an invasion of the tiny outpost, as he had been stunned by the fury elicited overseas by the attack on Copenhagen. Thornton sought to persuade him of the strategic advantages of capturing it, arguing that:

its position and great elevation, compared with the low shoaly and dangerous coast of the North sea, meant it was absolutely necessary for every vessel bound to or from the Eider, Elbe, Weser and Jade rivers to make the Island of Heligoland; so that menof-war stationed or cruising off it can as effectively secure the blockade of these rivers, at least, as if they were at anchor in the mouths of them.

Map 2 So unknown had Heligoland been to the Royal Navy that this 1787 Hamburg chart was practically the only one it had when Admiral Russell captured the colony in 1807. That October, the governor designate personally added to the chart the improvised signal mast (marked ‘a’ on the clifftop) that the islanders had voluntarily salvaged from HMS Explosion. (Public Record office)

Pondering on what had been said, Canning realised that it might become necessary to have a base from where his warships could conduct a rigorous blockade, especially against the Elbe. That river, being linked to the Baltic Sea by a small barge canal, offered the only overland route for naval stores for the Russian and Baltic ports, as long as the navigation of Denmark’s Sound and Belts was obstructed by British warships. Furthermore, it might even be wise to deny Heligoland to the French. By the weekend Canning had decided the invasion of the island should proceed. On Sunday 30 August 1807 a messenger arrived at Thornton’s lodgings with a letter from Canning urgently requesting him to ‘commit to paper your ideas upon the subject of taking Heligoland, and send them to me at this office as soon as you can convey tomorrow morning’.8 Thornton wrote hastily through that night. Working only by flickering candlelight, he distilled his observations and recommendations into a brief report. By noon the next day Canning had his report. Significantly, part of it read:

The garrison consists of just one Danish officer and twenty-five soldiers. There are two or three cannon mounted at one end of the rock, which have been hitherto used for the purposes of signalling rather than with any view to defence. . . . There is little doubt that the appearance of an English gun-brig would immediately determine the inhabitants to surrender; and a vessel that could throw shells into the town would put the surrender beyond all question.9

Most crucially Thornton also urged that after taking over the territory Britain should abide by the administrative status quo: ‘If any civil officer should be named for the purpose of internal regulations, he should be a person acquainted with the language and customs of the inhabitants.’ And such an officer ‘should not interfere with the government of the island’. His heartfelt conclusion read: ‘I would take the liberty to recommend that its internal government should be continued as it exists at present without any alteration.’

Just a few hours after those recommendations were received at the Foreign Office and had been copied and despatched post-haste to Admiral Russell, a far harsher military assessment arrived at the Admiralty. On 1 September 1807 they received a report from a virtually unknown British military official, Colonel J.M. Sontag. His hastily written secret paper, Attack upon the Danish Island of Heligoland, agreed that: ‘The taking possession of that island is of the greatest importance for Great Britain as it will enable the Navy to remain on that station the whole winter and afford an excellent shelter for their ships.’10 In terms of storming the island, Sontag advocated a far harsher approach than Thornton’s, suggesting that the inhabitants might be starved into surrender. The Heligolanders did not gather in their winter provisions until September, and the colonel noted that if a campaign began soon, ‘the want of provisions – for they need to obtain every necessary of life from the mainland – would compel them to surrender in less than two months’. Sontag was clearly a ruthless man, for he also suggested bombarding the island with a pulverising Copenhagen-style mortar attack: ‘To gain possession of it, it will be necessary to employ one or two frigates with some small ships of war to form the most strict blockade; one battalion of troops of the line, and also two bomb-vessels.’

Vice-Admiral Sir Thomas Russell’s flagship, the 74-gun Majestic – a veteran of the 1801 Battle of Copenhagen – had been keeping a sea watch just off Texel, the westernmost of the Dutch Frisian Islands. At 10am on 3 September 1807 the fast despatch vessel British Fair hove into view and came alongside. From it Russell received two ‘most secret’ dispatches. One was his sealed orders from the Admiralty, the other a copy of Thornton’s memo describing the island to Canning. Although Russell had been appointed commander-in-chief of the North Sea earlier that year, for an officer of his fighting qualities the Texel blockade had been especially frustrating because of the reticence of the Dutch squadron to allow him any opportunities for combat. The prospect of making some tangible strategic advance with regard to Heligoland was far more to his liking. Clearly eager to attack the island, he had been expecting that the orders to do so would arrive at any moment, as he had learnt from Viscount Falkland that Denmark had declared war. Consequently, on 30 August 1807, acting without authority from London, Russell ordered the Quebec, with the brigs Lynx and Sparkler, to establish an interim exclusion zone around the island to deprive it of all supplies and provisions.11

In fact it was only by chance that the admiral, who was to be fundamentally influential on the future of Heligoland, had ever gone to sea at all. By birth he had seemed destined to lead the life of a prosperous country squire. The son of an Englishman who had settled in Ireland, at the age of five Thomas Russell inherited a large fortune which by carelessness, or perhaps the dishonesty of his trustees, had disappeared before he was fourteen. This was probably what caused him to join the Royal Navy. Initially serving as an able seaman, he rose through the ranks to become a midshipman on a cutter in the North Sea. Although a blunt character, the misfortunes of his early life had beneficially imbued him with a powerful humanitarian spirit. By 1783 he was commanding a sloop off the North American coast, where he displayed both bravery and exceptional ship-handling skills in capturing in a storm the Sybile, a French warship considered to be the finest frigate in the world. For doing so Russell was offered a knighthood, which he modestly declined as he had not the fortune to support the rank with becoming splendour. In 1791, ten years before he was made a rear-admiral and did accept a knighthood, he commanded a frigate in the West Indies and won further distinction by securing the release of a British prisoner in Haiti’s St Domingo by threatening to bombard the town to ruins.12

In the letter authorising the seizure of Heligoland the Admiralty also informed Russell that, to assist him with the capture, they had already ordered to set sail from Yarmouth the troopship Wanderer, carrying 100 marines, and the bomb-vessels Explosion and Exertion. On 3 September 1807, by which time Russell was under way on the 160-nautical mile voyage from Texel to Heligoland, he sent a despatch to the Admiralty, reporting that he had just ‘given chase to five vessels to windward, to make out whether they may not be the bomb-vessels and their escorts, only to steer away for Heligoland, on the presumption they are destined for the capture of the island’.13 So the Majestic confidently pressed on, Russell remaining as yet unperturbed by the non-appearance of the reinforcements. He had, after all, the copy of Thornton’s letter in his pocket claiming that Heligoland’s garrison consisted of only some twenty-five troops.

At 2.30pm on 4 September HMS Majestic arrived off Heligoland and anchored between Sandy Island and Rock Island, menacingly close to the Lower Town. The Quebec lurked nearby with the brigs, all ready for action. What Russell had no means of knowing at that moment was that the Heligolanders were mightily displeased with their current lot. Even before the exclusion zone policed by Viscount Falkland had been imposed their supplies had been running low. For some weeks Napoleon’s ‘continental system’ and the resulting French pressure on Denmark had meant the islanders had been greatly impeded in their traditional occupations of fishing and piloting and so had been unable to make much of a living. Winter was approaching and they were, in effect, in the early stages of starvation. Initially, when the Quebec had arrived offshore a few days earlier, the island’s Danish Commandant, Major Von Zeske, had been determined to hold Heligoland for his country as long as he was able. But his resolve was now waning fast, influenced by the Heligolanders’ apparent reluctance to see their homes demolished before a surrender that appeared to be inevitable. Realising that his position was hopeless, at 6pm Major Zeske accepted a flag of truce and consented to a meeting with British officers the next morning.

The bomb-vessels and the troopship had still not arrived as Russell made ready to storm the island. He ordered a makeshift party of marines and seamen to be hastily assembled from the existing squadron. He was already anxious about the weather conditions and also became concerned that Major Zeske might be tempted to procrastinate, with the natural hope that so large a warship could not long continue to anchor so close to the town. His sense of urgency was clear in his letter demanding the island’s surrender, which his representatives handed to Major Zeske at dawn on 5 September 1807. Hoping that the aristocratic status of his negotiators might itself have some effect on Zeske’s position, Russell stated that the letter was ‘being delivered to your Excellency by Captain the Right Honourable Lord Viscount Falkland, assisted by my First Lieutenant, Corbet D’Auvergne (brother to His Serene Highness Rear Admiral the Duke of Bouillon)’. Expressing an evidently sincere concern to spare the islanders from bloodshed, he implored Zeske to ‘suffer me for the sake of Humanity to express a hope that your Excellency will not sacrifice the Blood and property of your inhabitants by a vain resistance, but that you will, by an immediate surrender, avert the horrors of being stormed’.14

Mindful of Thornton’s memo to Canning urging that the island’s ‘Internal government should be continued without any alteration’, Falkland and D’Auvergne agreed with Zeske that all such rights and customs would be safeguarded and respected. Unusually, there was an ongoing tradition that the islanders were not obliged to serve on board Danish naval ships, a privilege which should henceforth mean they would be exempt from service with the Royal Navy. The British representatives were in no mood to make any other allowances with regard to the military surrender: the garrison must lay down their arms, surrender themselves as prisoners-of-war and without their weapons leave forthwith on their parole d’honneur not to serve against Britain during the war. Zeske attempted to secure an undertaking that after the conflict the island would be returned to Denmark but this the naval officers refused to accept. At 2pm on the afternoon of 5 September the delegation returned to the Majestic with Zeske’s signature on the Articles of Capitulation, which Admiral Russell briskly ratified.

British possession of the island began immediately with the arrival of a 50-strong landing party led by Corbet D’Auvergne. Even so, the commencement of British rule could scarcely have been more makeshift. To keep a record of events in the new colony he was furbished by the Majestic’s purser with an unused muster book – traditionally used to record the ship’s company’s wages and attendance data; D’Auvergne duly took a quill pen and neatly altered the words ‘His Majesty’s Ship’ to ‘His Majesty’s Island of Heligoland’. He began by recording that, such was the high regard for Russell among the captains of the squadron, they had – without the Admiral’s consent – named the highest part of the new possession ‘Mount Russell’. The cliff-top that guarded it was now ‘Artillery Park’ and ‘D’Auvergne Battery’, below which was the inhabited part, now called ‘Falkland Town’.

The capture of Heligoland had been a peripheral but psychologically significant naval triumph, and news of it came as a welcome change at a time when virtually all the gains elsewhere in Europe were being made by Napoleon. Seizing this opportunity to raise the British public’s morale, the Admiralty circulated to the Press extracts of reports written by Sir Thomas Russell himself. Within a fortnight of the territorial acquisition these were prominently published in the London Gazette and even the Gentleman’s Magazine. By such means the public learnt of the admiral’s dash from Texel, the Danish representative’s surrender of the island, and Russell’s appointment of D’Auvergne as Acting Governor, because ‘his perfect knowledge of both services, zeal and loyalty and a high sense of honour made him the most competent officer for the role’. The extracts concluded with the news that, on the morning of 6 September, at the very moment the British occupation was starting, the reinforcements arrived: ‘the Explosion, Wanderer and Exertion hove in sight round the North End of the Island’.

But it might well have been a different story. By the time these extracts were on sale in the streets of London, Zeske and all the prisoners-of-war had been removed from the island, and shipped to mainland Europe for release. What was never revealed was the fact that the garrison’s strength was not ‘twenty-five Danish soldiers’, as Thornton had predicted, but 206 – more than eight times that!15 In fact, Colonel Sontag’s assessment of the need to bombard the island had fairly accurately predicted such a figure. Fortunately, Sontag’s report only reached Russell when HMS Explosion and the other reinforcements arrived, by which time the garrison had surrendered. Significantly absent from any of the officially sanctioned extracts published was any mention of the islanders themselves.

The Admiralty most carefully hushed up the real details of the reinforcements’ arrival. Russell had correctly reported in his letter of 6 September that ‘the Explosion, Wanderer and Exertion hove in sight round the North End of the Island’ – but his despatch did not conclude there. The sentence continued with the astonishing words: ‘when the two former almost instantly struck and hung on the Long Reef’. What happened next was recorded in Lieutenant D’Auvergne’s muster book. The good-natured islanders rushed to their boats to try to save the ships, even though they had been sent from Britain to threaten them with death. Wanderer was floated off, but the bomb-vessel Explosion had been too severely damaged below the waterline.16 Two days later, in fresh breezes and squalls, she broke free from the reef and drifted across the narrow anchorage to Sandy Island where she finally ran aground, a listing wreck.

The spontaneity with which the islanders had rushed to help, and the immediate rapport between them and the British seafarers, fostered excellent relations between the two sides. Indeed, the islanders welcomed the British almost as if they were long-lost relatives. (In a sense, of course, they were, as both the British and the Heligolanders were, to a greater or lesser extent, distant descendants of the Frisians.) This goodwill greatly helped D’Auvergne in his hurried efforts to strengthen Heligoland’s defences, lest the French should attack the island or Denmark attempt to recapture it. Under his directions the islanders themselves assisted in improving the ramparts of the cliff-top battery, which was to be the primary defensive position. The inventory of the captured Danish armaments provided grim reading. Of the dozens of abandoned cannon, virtually all were too rusty or poorly maintained to be functional.

Instead D’Auvergne turned his attention to the wreck of the bomb-vessel. With the islanders willingly providing most of the manpower, he set about salvaging all that might prove useful. First the Explosion’s fearsome 13-inch heavy mortars were brought ashore, as were her 68-pound cannon. Hauled aloft via the public oak staircase to Artillery Park they were duly installed at D’Auvergne Battery. Then, with great ingenuity, the islanders extracted the wreck’s towering top foremast and floated it over to Falkland Town; here, they hauled it up to the windswept plateau atop the 200ft-high red cliffs and raised it as an improvised signal staff, complete with yardarm. Ironically, at noon on 22 September 1807, it was there that the British flag was raised in commemoration of the coronation of King George III, with the Heligolanders loyally in attendance as the guns fired a twenty-one gun royal salute.17

Evidently an inspired choice for the role of governor, D’Auvergne was quickly winning the approval of all the islanders. By his conspicuous zeal, excellent judgement and suavity of manner, he managed, to a considerable degree, to reconcile the inhabitants to the changes which they were experiencing.18 One obscure incident helped to win him their affection. A few days after the surrender of Heligoland he was informed, on the authority of the magistrates, that there were forty families who had nothing to eat, not even bread, and no means of affording relief. D’Auvergne ordered the purser of the Majestic to deliver forty bags of bread to the island and directed him to see it impartially issued to the most needy families. On 16 September he wrote to Russell that virtually all the islanders were ‘destitute of almost every species of provisions except fish’, and to get them through the approaching winter he requested a shipment of 110 tons of rye, potatoes, flour and beef from England.19 Aware that all supplies from Denmark had been cut off, Russell readily agreed to the request (and remarked that in view of the Explosion’s demise he would take a pilot from the island with him to ensure the supplies arrived safely).

D’Auvergne’s kindness towards the islanders was in many other respects supported, indeed encouraged, by Russell. On appointing him Acting Governor on 5 September the admiral’s written instructions had emphasised the need to treat the islanders with respect: ‘You are to see that the inhabitants are treated with the greatest kindness; to conciliate their affections; and secure their attachment to our Government; as I hope it will never be given up.’20 Two days later Russell wrote to the Governor, movingly expressing his heartfelt good wishes to the Heligolanders:

Sir,Being on a point of sailing for England I am to request that you will acquaint the civil magistrates of your Government that I am so sorry that untoward circumstances have prevented my having the pleasure of being personally known to them.

Assure them that I shall do the utmost of my ability to represent them as a people worthy of the attention of our Government; and worthy of the privilege of a British Colony.

We have all noticed with joy the prompt, cheerful and effectual assistance given by your Inhabitants yesterday to HM ships the Explosion and Wanderer when aground, for which I pray Sir, that you will publicly advertise my thanks to them.

I commit you and them to God’s Holy care, and am with great respect.

SignedAdmiral, Sir Thomas Russell

The content of that moving letter was never made public by the Foreign Office, nor was the grateful letter of thanks sent a few weeks later to Governor D’Auvergne, and signed by every member of the Heligoland government:21

By these victuallings is the danger of famine decreased, which lay very heavy upon the breast of every inhabitant. Your Excellency has, while you procured us these benefits, given us a practicable proof of the gentle affectionate intention you maintain for us.

We acknowledge it with the warmest thanks that the Britannic Government gave us such a convincing proof of their humanity and generosity, and we hope that governance according to their general kindness all further months will see to commence.

Perhaps, then, it was not surprising that the British public also never got to hear the story of the forty bags of bread, or its postscript: that Russell had to personally intervene with the Admiralty to stop the parsimonious Victualling Board from debiting the Majestic for those bags of bread for the starving.22 Even the two-page Articles of Capitulation were kept secret, as was the admiral’s declared hope that the island ‘will never be given up’. There were other official clampdowns on the release of news. The loss of the Explosion and the consequent court-martial that September of its commander, Captain Elliot, were never brought to light. Nor was the trial of Viscount Falkland for an unrelated matter, although the disgrace resulted in altered place-names on Heligoland. Within a fortnight of the island’s capture Russell personally made sure that all the names of British officers, including his own, were deleted from the map.23