20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Robert Hale Non Fiction

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

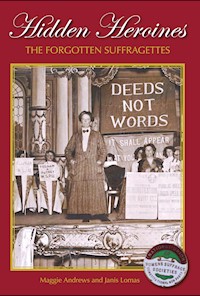

The story of the struggle for women's suffrage is not just that of the Pankhursts and Emily Davison. Thousands of others were involved in peaceful protest - and sometimes more militant activity - and they included women from all walks of life. This book presents the lives of forty-eight less well-known women who tirelessly campaigned for the vote, from all parts of Great Britain and Ireland and from all walks of life. They were the hidden heroines who paved the way for women to gain greater equality in Britain.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Hidden Heroines

THE FORGOTTEN SUFFRAGETTES

Hidden Heroines

THE FORGOTTEN SUFFRAGETTES

Maggie Andrews and Janis Lomas

ROBERT HALE

First published in 2018 byRobert Hale, an imprint ofThe Crowood Press Ltd,Ramsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

© Maggie Andrews and Janis Lomas 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 71982 762 4

The right of Maggie Andrews and Janis Lomas to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

Timeline

Introduction

Pioneering Victorian Women

1. Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827–91)Victorian suffrage campaignerJanis Lomas

2. Rose Crawshay (1828–1907)Philanthropist and Welsh iron-master’s wifeMaggie Andrews

3. Harriet McIlquham (1837–1910)Petitioner and local politicianLinda Pike

4. Charlotte Carmichael Stopes (1840–1929)Shakespearean scholar and proponent of the Rational Dress SocietyMaggie Andrews

5. Elizabeth Amy Dillwyn (1845–1935)Industrialist and novelistMaggie Andrews

6. Lady Henry Somerset (1851–1921)Leader of the Women’s Temperance MovementMaggie Andrews

7. Dame Ethel Smyth (1858–1944)Composer and campaignerJanis Lomas

The Movement Takes Off

8. Margaret Llewelyn Davies (1861–1944)Organizer of the Women’s Co-operative GuildMaggie Andrews

9. Mary Hayden (1862–1942)History don and Irish NationalistMaggie Andrews

10. Clemence Annie Housman (1861–1955)Author, illustrator, engraver, tax resister and census evaderMaggie Andrews

11. Millicent ‘Hetty’ MacKenzie (1863–1942)Professor, educationalist and campaignerMaggie Andrews

12. Lady Isabel Margesson (1863–1946)An eclectic supporter of multiple causesLesley Spiers

13. Alice Hawkins (1863–1947)Working-class militant and trades union organizerJanis Lomas

14. Constance Antonina (Nina) Boyle (1865–1943)Founder of the Women’s Police ServiceLisa Cox-Davies

15. Jennie Baines (1866–1951)Working-class firebrandJanis Lomas

16. Emma Sproson (1867–1936)‘Red Emma’Linda Pike

17. Countess Constance Markievicz (1868–1927)Irish Nationalist and the first woman elected to the House of CommonsMaggie Andrews

A Groundswell of Support

18. Ada Neild Chew (1870–1945)Socialist and mail-order entrepreneurJanis Lomas

19. Kitty Marion (1871–1944)Actress, hunger-striker and birth control campaignerJanis Lomas

20. Ada Croft Baker (1871–1962)Magistrate and aldermanCarol Frankish

21. Catherine Blair (1872–1946)Founder of the Scottish Women’s Rural InstitutesMaggie Andrews

22. Edith Rigby (1872–1948)Arsonist, WI activist and bee-keeperMaggie Andrews

23. Hannah Mitchell (1872–1956)Councillor and Justice of the PeaceJanis Lomas

24. Chrystal Macmillan (1872–1937)Advocate and peace campaignerMaggie Andrews

25. Margaret Bondfield (1873–1953)The first female minister in a British CabinetPaula Bartley

26. Adeline Redfern-Wilde (1874–1924)A working-class activist in the PotteriesAmy Dale

27. Alice Clark (1874–1934)Historian and shoe company executiveMaggie Andrews

28. Mrs Arthur Webb (1874–1957)Suffragist domestic goddessMaggie Andrews

Campaigners from All Walks of Life

29. Grace Hadow (1875–1940)Oxford don and NFWI Vice ChairmanElspeth King

30. Rosa May Billinghurst (1875–1953)Disabled militant suffragetteJanis Lomas

31. Mrs Aubrey Dowson (1876–1944)Editor ofThe Women’s Suffrage Cookery Book Jenni Waugh

32. Princess Sophia Duleep Singh (1876–1948)The suffragette princessCarol Frankish

33. Muriel Matters (1877–1969)Campaigner and Montessori teacherJanis Lomas

34. Mabel Lida Ramsay (1878–1954)A doctor and suffragist in PlymouthMaggie Andrews

35. Margaret Cousins (1878–1954)Irish Nationalist, Theosophist and magistrateLeah Susans

36. Kate Parry Frye (1878–1959)Impoverished suffrage organizer and palm readerJanis Lomas

37. Nora Dacre Fox (1878–1961)Suffragette and FascistMaggie Andrews

38. Margaret Wintringham (1879–1955)From schoolteacher to politicianMaggie Andrews

39. Mary Macarthur (1880–1921)Trade union leader and adult suffragistAnna Muggeridge

The Next Generation

40. Vera ‘Jack’ Holme (1881–1962)The suffragette chauffeurJanis Lomas

41. Anna Munro (1881–1962)Scottish orator and Women’s Freedom League campaignerRose Miller

42. Mary Gawthorpe (1881–1973)Teacher, WSPU organizer and Labour campaignerJanis Lomas

43. Helena Normanton (1882–1957)Pioneering barristerHolly Fletcher

44. Elsie Howey (1884–1963)Joan of Arc and suffragette warriorMollie Sheehy

45. Annie Barnes (1887–1982)Stepney councillorMaggie Andrews

46. Dora Thewlis (1890–1976)Baby suffragetteJanis Lomas

47. Ellen Wilkinson (1891–1947)Communist and cabinet ministerPaula Bartley

48. Lilian Lenton (1891–1972)Militant, hunger striker and escape artistJanis Lomas

Notes

Index

To Neil, Clare, Laura, Emily, Tom, David and Gregg, Lynton, Oli and Sophie, Dom and Sonya, Annie and Peter, Lucia, Erin, Edu, Florence and Stanley.

May your lives live up to the dreams and hopes that the hidden heroines of this book have struggled to realize.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is the product of numerous scholars of women’s suffrage history. We owe a huge debt and thanks to the writers and experts such as Elizabeth Crawford, Leah Leneman, Jill Liddington, Angela John, June Purvis1 and many others whom we have encountered, particularly through the Women’s History Network, and drawn upon here.

Friends and colleagues Paula Bartley, Carol Frankish, Lesley Spiers and Jenni Waugh have provided support, discussion and the biographies of women. University of Worcester students have also contributed to writing the histories of individual women for this book: undergraduates studying History or Law – Holly Fletcher, Mollie Sheehy and Leah Susans – as well as postgraduates – Amy Dale, Lisa Davies, Elspeth King, Rose Miller, Anna Muggeridge and Linda Pike. Thank you all. We hope that you never lose your interest and enthusiasm for women’s history.

Our families have, as ever, lived with our enthusiasm, exhaustion and preoccupation as we have struggled our way through completing this text. A huge thank you, as always, goes to Neil and John for all their love, support and shopping undertaken while we were writing. Thank you also to the good-natured forbearance of the next generations: Neil, Clare, Laura, Emily, Tom, and to David and Gregg, Lynton, Oli and Sophie, Dom and Sonya, Annie and Peter, Lucia, Erin, Edu, Florence and Stanley.

ABBREVIATIONS

AFL

Actresses’ Franchise League

BWSS

Birmingham Women’s Suffrage Societies

BWTA

British Women’s Temperance Association

CUWFA

Conservative and Unionist Women’s Franchise Association

ELFS

East London Federation of Suffragettes

ILP

Independent Labour Party

IWFL

Irish Women’s Franchise League

LNS

London National Society

LWLL

Leeds Women’s Labour League

MLOWS

Men’s League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage

MNSWS

Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage

NCSWS

New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage

NFWW

National Federation of Women Workers

NLOWS

The National League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage

NUSEC

National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship

UNWSS

National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies

SWH

Scottish Women’s Hospital

SWRI

Scottish Women’s Rural Institutes

TRL

Tax Resistance League

WEC

Women’s Emergency Corps

WEU

Women’s Emancipation Union

WFL

Women’s Franchise League

WFL

Women’s Freedom League

WNASL

Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League

WSPU

Women’s Social and Political Union

WTUL

Women’s Trade Union League

WVR

Women’s Volunteer Reserve

TIMELINE

1832

The Great Reform Act is passed, extending the electorate to about 12 per cent of men. The first women’s suffrage petition is presented to Parliament by Henry Hunt MP.

1867

Second Reform Bill goes before Parliament. A women’s suffrage petition with nearly 1,500 signatures is presented to the House of Commons. Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage formed. London National Society formed.

1881

Women are enfranchised on the Isle of Man.

1884

Third Reform Bill is passed, extending the franchise to approximately 60 per cent of men. An amendment to include women is rejected.

1894

The Local Government Act is passed, enabling some married and single women to vote in elections for county and borough councils.

1897

Twenty suffrage societies amalgamate to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

1902

Women textile workers from the north of England present a petition with 37,000 signatures to Parliament asking for votes for women.

1903

Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) is formed by Emmeline Pankhurst.

1905

First militant act: Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney are arrested and imprisoned in Manchester.

1906

WSPU moves its headquarters from Manchester to London.

1907

Qualification of Women Act allows women to be elected onto borough and county councils and become a mayor. There is a split in the ranks of the WSPU. The Women’s Freedom League (WFL) is formed by the breakaway group of suffragettes.

1908

H.H. Asquith, who is implacably opposed to women’s suffrage, becomes prime minister. Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League (WNASL) is formed. WSPU organizes the Women’s Sunday demonstration in Hyde Park. 250,000 people attend from across the country; it is the largest ever political rally in London.

1909

The first forcible feeding of suffragette hunger strikers in prison takes place. The Tax Resistance League is formed, adhering to the principle of no taxation without representation.

1910

The National League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage (NLOWS) is formed from an amalgamation of the Men’s League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage and the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League. The First Conciliation Bill, which would have enfranchised one million women, fails to become law, resulting in an escalation of suffragette violence.

1911

The Liberal Government is re-elected. The Second Conciliation Bill, which would have given a limited number of women the vote, passes its second reading with a large majority. Suffrage activists are optimistic. In November, the bill is ‘torpedoed’ by the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith. The WFL organizes a boycott of the 1911 Census.

1912

Window-smashing campaigns start in earnest and Christabel Pankhurst flees to Paris. The WSPU splits again. The NUWSS forms an alliance with the Labour Party, which agrees to campaign for women’s suffrage and to include this in its manifesto.

1913

There are widespread bomb and arson campaigns. Prisoners’ Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health (‘Cat and Mouse’) Act is passed, enabling women on hunger strike to be released from prison and then re-arrested a few days later, once their health has improved. Suffragette Emily Wilding Davison dies from injuries received on Derby Day. The NUWSS organizes a pilgrimage of law-abiding suffragists from across the country, which culminates in a rally of 50,000 people in Hyde Park.

1914

The violence continues until Tuesday 4 August, when war is declared. Suffragette prisoners are released. The WSPU declares a cessation of violence.

1917

House of Commons begins the process of passing the Representation of the People Act, granting the vote to women aged 30 or above with the necessary property qualifications.

1918

The enfranchisement of some women finally becomes law on Wednesday 6 February. The Parliamentary Qualification of Women Act is passed in November. Women vote for the first time on Saturday 14 December. Of the seventeen women who are parliamentary candidates, only Constance Markievicz wins her seat, but, as a member of Sinn Féin, she never sits in the House of Commons.

1919

NUWSS re-named National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC). Nancy Astor becomes the first woman to take a seat as an MP.

1928

Women entitled to vote on same terms as men. Emmeline Pankhurst dies.

1929

The first general election where women can vote on the same terms as men produces fourteen women MPs. Margaret Bondfield becomes the first female member of the British Cabinet. Millicent Garrett Fawcett dies.

INTRODUCTION

ON SATURDAY 14 December 1918, some women voted in a parliamentary election for the very first time in Britain. Earlier that year, the Representation of the People Act had passed into law and given the franchise to those women who were both aged thirty or over and also met the property qualifications. According to the Leeds Mercury, an experienced poll clerk had reported that the December poll was one of the ‘jolliest of all elections’ he had experienced. The paper went on to explain:

At this particular booth it had been a day of smiles. Nine out of ten of the women voters had a smile for the policeman at the door of the room of secrets, and he, gallant man, returned the glad look unfailingly.

Inside the room the poll clerks, men and women dispersed smiles with the ballot papers, and the Presiding Officer, a grave man usually, and fully aware of the dignity of his office, could not help himself. He smiled with the rest….

In all five divisions of the city the women displayed an unexpected keenness and enthusiasm in exercising their vote. At one booth a number of women turned up a few minutes before eight o’clock in the morning and they waited in a queue until the hour struck.1

This election was the culmination of years of struggle and campaigning by thousands of women from all walks of life and in all parts of the country. Many have heard of the role played by the Pankhurst family in the struggle to win the vote 100 years ago. History books often tell of the windows that were smashed, the post boxes that were set on fire, and the marches that took place in London and Manchester. Some of the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement are publicly celebrated: Emmeline Pankhurst’s statue can be found in Victoria Gardens, in the shadow of the House of Commons, a visual reminder of one of the heroines of this infamous struggle that disrupted the capital in the Edwardian era. The centenary of women’s suffrage is being marked by the erection, in Parliament Square, of a statue of Mrs Fawcett, the leader of the National Women’s Suffrage Societies, recognizing another heroine of the women’s suffrage movement. There were, however, many other women in other parts of Britain and Ireland, including Cardiff and Cumbria, Edinburgh and Glasgow, Leeds and Leicester, County Sligo and Dublin, Preston and Plymouth, Warwickshire and Wolverhampton, who also marched and campaigned, gathered signatures for petitions, organized pilgrimages, burned down football stands, boycotted the census, scored graffiti on churches, refused to pay their taxes, chaired meetings, and risked both ridicule and their freedom fighting to obtain for women the right to vote.

This book is about the lives of forty-eight of these hidden heroines and the part they played in the campaign for women to become full citizens of the United Kingdom, able to cast a vote in parliamentary elections. They are a sample of the thousands and thousands of women involved in years of campaigning. Their stories, their struggles and sacrifices demonstrate that support for the suffrage come from all classes and all walks of life: Catherine Blair and Mrs Arthur Webb were brought up on rural farms in Scotland and Wales, respectively; Lady Henry Somerset and Princess Sophia Duleep Singh lived in palatial surroundings, but many more came from much more modest backgrounds – Alice Hawkins and Jennie Baines lived in working-class terraced houses in Britain’s industrial towns and cities.

The exploration of these women’s lives before, during and after their involvement in the suffrage campaigns demonstrates the multiplicity of political persuasions, interests, inclinations and social issues that women were involved in. Their lives convey the complex range of responsibilities, social expectations, sacrifices, struggles and priorities that women had to navigate to undertake suffrage activities. Some were wives and mothers; for them, there were issues about who would look after their home and children if they were imprisoned after a run-in with the police. Some had the benefit of an independent income; others were struggling to earn a living and had to consider carefully the consequences of any action they might take on their employment prospects. Some were confident public speakers, easily able to cope with heckling and abuse; others had to conquer their fear of speaking in public. Many paid a high price in terms of damage to their mental and physical health for their part in suffrage campaigns, which was frequently accompanied by antagonism not only from strangers, but also often from within their own families. It is no coincidence that many of these women were outsiders, loners, marginalized in many ways and for many reasons from society.

When, in 1912, at a suffrage meeting at the Royal Albert Hall in London, Emmeline Pankhurst encouraged women to ‘Be militant each in your own way’, and incited the meeting to rebellion2 she was giving voice to an already existing situation: women were already rebelling against a political system that treated them as second-class citizens, and they had been doing so in numerous different ways for many years. The struggle for women’s suffrage was long and slow and, overall, painstakingly polite and peaceful in its methods. It was an example of the exasperating powerlessness of political campaigning for the disenfranchised. It was the misnamed Great Reform Act of 1832 that specifically restricted the right to vote in parliamentary elections to ‘male persons’. The inequality of this was not lost on women, and the first petition for women’s suffrage appeared soon after. Over the next sixty-five years, further petitions were put together to try to persuade Parliament to introduce a women’s suffrage bill, or to amend parliamentary reform acts to include women’s suffrage – all to no avail. In 1866, John Stuart Mill presented the first mass petition of women to Parliament. It contained nearly 1,500 signatures, gathered in just two weeks by a group of determined women, from across the country, including Scottish mathematician and scientist Mary Somerville, Priscilla Bright McLaren, who had been involved in the anti-slavery campaigns and became president of the Edinburgh Women’s Suffrage Society. Frances Buss, a pioneer of women’s education and Josephine Butler, who campaigned against the sexual exploitation of women were also signatories.3

The petition, although unsuccessful, galvanized many women and, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, pro-women’s suffrage events, activities, campaigns and societies blossomed and caused some alarm. In July 1875, the Edinburgh Evening News announced:

The opponents of female suffrage felt that the movement for the extension of the franchise to women is becoming so serious that it must be met by a rival organisation. An Anti-suffrage Suffrage Society has accordingly been started under influential political direction.4

In March 1880, over three thousand people gathered to hear a speech on Women’s Suffrage by Lydia Becker of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage; an event probably organized by the Norwich Committee for Women’s Suffrage.5 In discussions about which women should have the vote and why, a meeting held in Bangor, North Wales, in November 1883 heard one proponent of women’s suffrage suggest that only women who were householders should be able to vote, while another suggested women tea drinkers should have the vote to counteract the influence of male beer drinkers. The meeting also heard anxiety expressed about what the effect women’s enfranchisement might have on the two main political parties.6 For the next thirty years, concern over the possible influence of women voters on the fortunes of the Liberals and the Conservatives and the determination of the leaders of parties to oppose any change to the suffrage that might disadvantage them, played a major role in denying women the right to vote.

In 1889, an ‘Appeal Against Female Suffrage’ was launched, which a number of women enthusiastically signed. Party allegiance and political self-interest were not the only reasons for the antipathy to enfranchising women. It was argued that most women were not interested in politics; that their natural sphere of influence was the home and motherhood; and that involving them in politics would upset the natural order of both society and the home. Undeterred, a Private Members’ Bill was introduced into Parliament in 1892, only to be defeated by twenty-three votes. Another petition was launched and displayed in Westminster Hall in 1896 to coincide with Mr Faithfull Begg’s Parliamentary Franchise (Extension to Women) Bill. This petition had 257,796 names on it, with signatures from every constituency in the country.7

In 1897, numerous suffrage groups were brought together beneath one umbrella organization – the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), under the leadership of Mrs Millicent Fawcett. This was by far the largest suffrage organization, which, by 1909, had over 50,000 members.8 In 1903, frustrated by the slow progress of the genteel campaigning of many women’s suffrage societies, Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters formed the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in Manchester. It was this new organization, particularly after it moved to London, that developed many inventive methods of gaining publicity for their cause – methods that included creating disturbances at political meetings, attempts to storm the House of Commons, mass window-smashing, arson and the destruction of property. In 1906, a Daily Mail headline writer coined the word ‘Suffragette’ to refer to those campaigners who used these more militant tactics, but the term was often used interchangeably with the term commonly used to describe law-abiding campaigners – ‘suffragists’.

Among women’s suffrage campaigners there were differences of opinion about both tactics and priorities. The publicity that the militant tactics received and the bravery of the women involved initially gained admiration from across the suffrage organizations. At the Savoy Hotel on Tuesday 11 December 1906, a banquet was held for released prisoners, chaired by Mrs Fawcett of the NUWSS.

However, in time many of the law-abiding suffragists in the NUWSS became very uneasy about the more extreme activities of the WSPU supporters who damaged property such as pillar boxes, large houses, paintings in galleries, the tea house at Kew gardens and sporting venues and, consequently, inconvenienced ordinary people. These actions caused a backlash against suffrage campaigners from some of the general public. Furthermore, operating a militant group that broke the law was in many ways incompatible with running a democratic organization and, in 1907, a number of the members complaining about Mrs Pankhurst’s autocratic leadership left the WSPU and formed the Women’s Freedom League (WFL). Charlotte Despard became the leader of this organization, which undertook a form of militancy that involved passive resistance. They were the main instigators of the Census Boycott in 1911.9 The lives of the forty-eight women discussed in this book suggest that the antagonism and splits between the militant and non-militant groups within the suffrage movement should not be exaggerated. For example, Isabel Margesson worked with the NUWSS, the WSPU, the WFL and the Tax Resistance League (TRL) simultaneously, and there are numerous instances of the different factions and groups within the suffrage movement sharing platforms at meetings, organizing joint processions and events.

One of the strategic differences of opinion amongst women’s suffrage campaigners was how much emphasis to place on the symbolic significance of granting the vote to any one group of women. Initial campaigners sought to enfranchise single women or women householders only; the main suffrage groups requested the vote for women on the same terms as men, but the majority of men could not vote in the nineteenth century. Indeed, even in 1914, at the eve of the First World War, fewer than 60 per cent of men were enfranchised. The right to vote was based on either owning or renting property of a sufficient value, and in some of the poorer districts of the country, such as Glasgow, half of men were also excluded from the franchise. Enfranchising women on the same terms as men would have left many working-class men and women without the vote. A number of Conservative politicians were inclined towards enfranchising wealthier women who they considered most likely to vote Conservative; while Liberals were concerned that enfranchising women on the same terms as men would favour the Conservatives. The Labour party favoured adult suffrage, and Margaret Bondfield, who was chairperson of the Adult Suffrage Society, became the first female cabinet minister in Labour’s 1929 administration, just one year after universal franchise was finally introduced throughout Britain.

A multitude of suffrage groups appeared in the Edwardian era; some, like the Barmaids’ Political Defence League and the Gymnastic Teachers’ Suffrage Society, were quite niche. The TRL was formed as an offshoot of the WFL in 1909, based upon the idea of no taxation without representation, with members refusing to pay a variety of taxes. Clemence Housman did not pay inhabited house duty whilst Emma Sproson resisted paying her dog licence, one of the only taxes working-class women paid. Women’s suffrage supporters often had multiple allegiances to a number of organizations. As Hilary Frances points out, whilst some of the WFL members belonged to no other organization, the women who joined the TRL:

belonged to a number of other societies, including the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the New Constitutional Society, the Conservative and Unionist Women’s Franchise League, the Church League for Women’s Suffrage, the Actresses’ Franchise League, the Artists’ Franchise League, the Women Writers’ Suffrage League’.10

In 1909, the Liberal government introduced a Suffrage Bill, which would have enabled approximately one million women, and virtually all men, to vote, giving many suffrage campaigners the hope they were at last making progress. But when an election was called and the new government prioritized other issues, the WSPU responded by stepping up their militancy and there was a matching increase in violence by the police attempting to suppress the women’s efforts to win the vote. On Friday 18 November 1910, the WSPU sent a delegation to the House of Commons. Some of these delegates were assaulted in ensuing clashes with the police, and the day became known as ‘Black Friday’. Emmeline Pankhurst’s sister, Mary Jane Clarke, a paid organizer of the WSPU in Brighton, was amongst 156 women arrested and sent to Holloway Prison, where she was forcibly fed. Although she spoke at a WSPU ‘welcome’ luncheon after her release on the 23 December, two days later she was dead, the first martyr of the suffrage movement.

In selecting the forty-eight women to be included in this book, we have avoided any of the families of well-known women’s suffrage leaders. A few of the women we have chosen you may have heard of; you have seen the names of one or two inscribed on the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square.11 Others will be totally unknown outside the particular geographical region, political or interest group to which they belonged. We have found traces and mentions of numerous other women about whom very little is known or able to be known. For example, Elizabeth Crawford has tried to track down Susan Cunnington, a Brighton teacher who donated five shillings to the WSPU in 1911. She was the principal of a private girls’ day school in Brighton who from a modest background went to Girton College, Cambridge, and wrote a mathematics textbook, but little else is known about her.12 Similarly, we have not been able to trace what Miss Laura E. Price did as a secretary for the NUWSS that led to her receiving praise for her role in the movement from Mrs Fawcett in 1924. Her letter remains a tantalizing reminder of how many suffrage campaigners remain hidden from history.

Letter to one of the hidden heroines of the suffrage movement from Millicent Fawcett, leader of the NUWSS. GILL THORN

Contemporary understanding of the women, and some men, who sought to drum up support for women’s enfranchisement, is shaped by the historical sources that have survived, and this makes it particularly difficult to trace the lives and work of the law-abiding suffrage societies. Newspapers in the early twentieth century tended to focus their coverage on the more spectacular events of the WSPU and the activities of celebrity campaigners. There is, for example, a multitude of newspaper coverage of the exploits of Mrs Pankhurst, but only occasional mentions of the foot soldiers of women’s suffrage movement. Public meetings receive perfunctory attention, arrests and court appearances are described while the speeches that ordinary women made in court are rarely reported.13 Those women who, perhaps because of other responsibilities, were only able to make donations to suffrage societies or sell suffrage newspapers on street corners, left little record of their activities.

A few women, like Hannah Mitchell, wrote their autobiographies; others, like Kate Parry Frye, kept a diary. Even so, such insights into the lives of women in this era are rare, particularly if they are working class. Some records have survived from the suffrage organizations, but they contain little of what life was like for the ordinary suffrage campaigner who traipsed door to door trying to drum up support for the movement, or who organized bazaars and fêtes to raise money, sewed banners, and tried to encourage women to attend meetings. Their stories were no more newsworthy then than they would be today. Yet, without the efforts of the women who did these things and who chaired meetings and sat in audiences and were quietly heroic, the movement for women’s suffrage would not have been successful.

Popular mythology has often suggested that the suffrage campaigns came to a halt on the outbreak of the First World War as women threw themselves into the war effort and were rewarded with the franchise in 1918. The life stories of these forty-eight women suggest a far more complex story. Some women, like Chrystal Macmillan, opposed the war and campaigned for a negotiated peace throughout the conflict. Many women with a strong background in philanthropy undertook welfare work. Some found the conflict offered them new career opportunities; for example, Mrs Arthur Webb became something of a domestic guru. When the wartime coalition government granted the vote to some women in 1918, seventeen women put themselves forward as candidates for Parliament in the 1918 election. Many are included in our chosen forty-eight. Like Nora Dacre Fox, they were unsuccessful and are largely forgotten. Only one woman, Countess Markievicz, won her seat, but as a member of Sinn Féin did not sit in the House of Commons; and, although well known in Ireland, she receives little attention across the water and so we have included her here, along with Margaret Wintringham, the first English-born woman to become an MP.

The biographies of these forty-eight hidden heroines demonstrate the multiplicity of political persuasions, interests, views, hopes, dreams and ideals that women had, which they found either combined with or collided with their campaigning for women’s suffrage. Many belonged to other women’s groups, temperance societies, the Women’s Co-operative Guild, the women’s sections of political parties, or women’s trades unions. Some, like Grace Hadow and Edith Rigby, went on to take a very active role in the Women’s Institute movement, which formed in 1915, and campaigned to improve rural women’s lives. The vote, for many women was but one part of a re-working and re-imagining of women’s role in the public sphere. A number of the women campaigning for the suffrage were pioneers in their fields of work: they were doctors, writers or became radio broadcasters, barristers and magistrates in the inter-war years, once the Sex Disqualification Removal Act was passed in 1919. For many women in the suffrage era, teaching provided an acceptable and attainable job. It was through education, it was hoped, that women would gain entry to employment and be able to interact with men as equals. In many ways, teaching was seen as an extension of women’s domestic role of nurturing children, an area in which women, by virtue of their gender, could be acknowledged as experts. It is no coincidence that the first professor in Britain, Millicent MacKenzie, was a professor of education. She and a number of other women whom we have included championed new innovative experimental approaches to learning – the ideas of Rudolph Steiner, Montessori or Froebel.

Many of the women featured in this book were politically motivated and public-spirited before, during and after the suffrage campaigns. Householder women could vote and stand in local elections, for school boards, prison boards and as Poor Law guardians, from as early as the 1870s. Women like Annie Barnes and Ada Croft Baker took an active role in local politics in the inter-war era, whilst Ellen Wilkinson moved from the suffrage campaigns into national politics and became a government minister during the Second World War. But for a significant number of women, their utopian dreams of a better, brighter future when women took part in the political process gravitated towards Eastern religions. Many suffrage campaigners were vegetarian years before it was popular or fashionable, and campaigned against cruelty to animals. Margaret Cousins and Elsie Howey were not alone in their enthusiasm for Theosophy, a movement founded in 1875 by Helena Blavatsky, which seeks understanding of the mysteries of life and nature through the unity of religion, science and nature to bring about the happiness of humanity.14

The forty-eight women discussed here are but a tip of the iceberg of the thousands of women who have in the past and continue now to campaign to improve women’s lives in society in Britain and elsewhere. They deserve to be remembered and recognized as heroines of the Women’s Movement. But behind them are the many millions of women they fight for: women for whom carrying on with the daily grind of everyday life is in itself heroic.

Pioneering Victorian Women

1

BARBARA LEIGH SMITH BODICHON (1827–91)

Victorian suffrage campaigner

Janis Lomas

In 1857, Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon wrote:

I am one of the cracked people of the world, and I like to herd with the cracked … queer Americans, democrats, Socialists, artists, poor devils or angels; and am never happy in an English genteel family life. I try to do it like other people, but I long always to be off on some wild adventure, or long to lecture on a tub in St. Giles, or go to see the Mormons, or ride off into the interior on horseback alone and leave the world for a month…. I want to see what sort of world this God’s world is.1

Barbara Leigh Smith was the eldest of Benjamin Leigh-Smith and Anne Longden’s five children. Her mother was a milliner and her father a radical MP, a Dissenter, a Unitarian, and a benefactor to those less fortunate than himself. Anne Longden met him when he visited his sister in Derbyshire, and when she became pregnant Benjamin moved her to Sussex and rented a lodge for her where Barbara was born in April 1827. Benjamin lived at his own house nearby, Brown’s Farm, but visited his family daily and eight weeks after Barbara was born her brother was conceived. After his birth, the family went to America for two years. On their return, they lived openly together, but after her fifth pregnancy Annie became ill with tuberculosis, and when Barbara was just seven years old her mother died. Barbara’s biographer Pam Hirsch suggests that it could have been Benjamin’s objection to the marriage laws, which would have made a wife and children his property, that prevented her parents marrying.2 Whatever the reason, Barbara felt the stigma of her illegitimacy for the rest of her life. Her cousin Florence Nightingale and the rest of the Nightingale family refused to acknowledge the existence of Barbara or any of her siblings. Barbara’s father played a large part in her childhood, which she spent in Hastings, and, like all her siblings, when she was twenty-one she received investments, which provided an income of £300 a year. Barbara as a financially independent woman gave generously to help people less fortunate and supported her many friends her whole life. Importantly, her money also allowed her to take up the cause of women’s rights and fight for change.

Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon. THE WOMEN’S LIBRARY COLLECTION, LSE LIBRARY

Perhaps due to her unusual upbringing, Barbara’s views in relation to women’s work and education were ahead of her time. Her brother Ben studied at Jesus College, Cambridge, but, as universities were not then open to women, she attended Bedford College and studied art, becoming a skilful artist. Years later she wrote:

… ever since my brother went to Cambridge I have always intended to aim at the establishment of a college where women could have the same education as men if they wished it.3

She was unconventional and, in her early twenties, she embarked on an extensive, un-chaperoned walking tour of Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and Austria with her friend Bessie Parkes. While abroad, they decided to stop wearing corsets and to shorten their skirts to four inches above their ankles as they were so uncomfortable. Barbara celebrated her freedom in a little verse she wrote:

Oh! Isn’t it jolly/To cast away folly/And cut all one’s clothes a peg shorter/And rejoice in one’s legs/Like a free-minded Albion’s daughter.4

Barbara may not have been a great poetess, but her ditty celebrated their jollity and freedom, three decades before the Rational Dress Society advocated the abandonment of restrictive corsets. By the age of twenty-five, Barbara had established her own progressive school in London with Bessie Parkes’s help. It was an experimental school, non-religious, co-educational, and admitted children of differing class backgrounds; other experimental ideas followed. In the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s, Barbara was a leading figure in four major campaigns: for married women to be given independent status under the law; for women’s right to work; for women to have an equal education to men; and for women to be allowed to vote.

In 1854, Barbara wrote an influential pamphlet titled A Brief Summary, in Plain Language, of the Most Important Laws concerning Women. In her opening remarks, she acknowledged the importance of the vote for women:

… a single woman has the same rights to property, to protection from the law, and has to pay the same taxes to the State as a man. Yet a woman of the age twenty-one, having the requisite property qualifications, cannot vote in elections for Members of Parliament.5

She saw clearly that if married women had the right to their own property and earnings, it would make it harder for politicians to refuse to give women the vote. She was asked to give evidence to the Law Amendment Society, which was looking into the legal position of married women. Its deliberations led to the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act being passed, allowing divorce for the first time outside the ecclesiastical courts and the Houses of Parliament, making divorce possible for more couples through a separate civil divorce court. Although the law was by no means equal, it did protect the property rights of divorced and separated women, something that Barbara had campaigned for.

However, for married women the position remained unchanged: when a woman married, her husband controlled her possessions, earnings and property and she could not dispose of any belongings without his consent. Barbara formed a committee, the Langham Place Group, to try to change the law. Within a year, Barbara’s committee had become a nationwide campaign group, and she drafted a petition, which, when presented to the House of Lords in March 1856, had 26,000 signatures on it and was the first petition organized by a woman in the UK. Unsurprisingly, it was rejected; it took until 1870 for the first Married Women’s Property Act to be passed, and a further twelve years until a more comprehensive act finally gave women the rights to both their own property and their earnings. Barbara campaigned for these changes throughout that period.

In 1857, Barbara published Women and Work, arguing that a married women’s dependence on her husband was degrading. Her views on the legal position of married women led her to say she would not marry, as she was fearful of losing her independence. Yet, in 1857, she met Eugene Bodichon, and compromised her principles by marrying this French doctor. She hoped to have children and did not want her children to be illegitimate, as she had been. Eugene lived in Algeria, North Africa, for much of his life. He dressed in Arab robes, spoke little English and was seventeen years older than Barbara, but he shared Barbara’s radical political views and loyally supported Barbara in her many campaigns for women’s rights. Unsurprisingly, their marriage was unconventional. He continued to live in Algeria, and Barbara travelled to and fro, between winters in Algeria and her campaigning in London. Her family was shocked by her marriage, and her father set up a trust to safeguard her money. As a result, she had less freedom as she now had to ask the trustees before spending money. Eugene treated poor patients for free and had no money of his own. Although at first they were happy, in time their differences became more marked and Barbara spent more time in England where Eugene refused to live. She remained loyal to him; they wrote to each other when separated; and she paid all his bills, even when he began to drink heavily and had dementia. Barbara even sold her London home to pay for live-in help for him.