8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

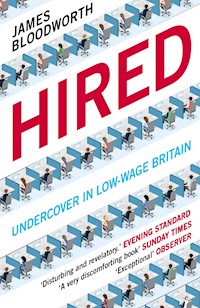

Longlisted for the Orwell Prize, 2019 ____________ The Times Round-up of the Best Non-fiction Paperbacks, 2019 TheTimes Best Current Affairs and Big Ideas Book of the Year, 2018 'A very discomforting book, no matter what your politics might be... very good' Sunday Times 'Potent, disturbing and revelatory' Evening Standard We all define ourselves by our profession. But what if our job was demeaning, poorly paid, and tedious? Cracking open Britain's divisions journalist James Bloodworth spends six months living and working across Britain, taking on the country's most gruelling jobs. He lives on the meagre proceeds and discovers the anxieties and hopes of those he encounters, including working-class British, young students striving to make ends meet, and Eastern European immigrants. From the Staffordshire Amazon warehouse to the taxi-cabs of Uber, Bloodworth narrates how traditional working-class communities have been decimated by the move to soulless service jobs with no security, advancement or satisfaction. This is a gripping examination of Brexit Britain, a divided nation which needs to understand the true reality of how other people live and work before it can heal.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

‘Exceptional … Bloodworth is the best young left-wing writer Britain has produced in years.’

Nick Cohen, Observer

‘A very discomforting book, no matter what your politics might be … very good.’

Rod Liddle, Sunday Times

‘Potent, disturbing and revelatory … Bloodworth sets out to see something we should know more about than we do, and he tells the story of what he found well.’

Evening Standard

‘A wake-up call to us all. A very graphic and authentic journey exposing the hard and miserable working life faced by too many people living in Britain today.’

Margaret Hodge MP, former Chair, Public Accounts Committee

‘I emerged from James Bloodworth’s quietly devastating and deeply disturbing book convinced that the “gig economy” is simply another way in which the powerful are enabled to oppress the disadvantaged.’

D. J. Taylor, author of Orwell: The Life

‘Grim but necessary reading … Theresa May should horrify Bloodworth by picking up a copy of Hired and learning from it.’

Spectator

‘Unflinching … a refreshing antidote to the fashionable post-work theses written from steel-and-ivory towers.’

Prospect

___

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

James Bloodworth is a journalist, broadcaster and author. He writes a weekly column for the International Business Times and his work has appeared in the Guardian, New York Review of Books, New Statesman and Wall Street Journal. He is the former editor of Left Foot Forward, an influential political blog in the UK.

@J_Bloodworth

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2018 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This edition published in 2019

Copyright © James Bloodworth, 2018

The moral right of James Bloodworth to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 016 2

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 015 5

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

___

CONTENTS

Preface to paperback edition

Introduction

Part I: RUGELEY

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Part II: BLACKPOOL

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Part III: SOUTH WALES VALLEYS

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Part IV: LONDON

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Epilogue

Notes

Index

Life is good, and joy runs highBetween English earth and sky

William Ernest Henley,‘England, My England’

___

PREFACE TO PAPERBACK EDITION

From the vantage point of 2018, the world of three years ago (when I left London to write this book) feels like an entirely different era. Political life since 2016 has been convulsed by various incarnations of populism. Politicians who offer simple solutions on the back of underlying resentment are in the ascendance. Growing sections of the public in western democracies are looking for someone to blame and someone to follow.

Much of this political backlash has been framed in moral terms. The Brexit vote is said to have been driven by a Russianbacked campaign of ‘misinformation’. The relative success of left-wing Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn at the 2017 General Election (though he still failed to win) is interpreted as a product of irresponsible youthful idealism. The rise of Donald Trump to the presidency of the United States is treated as a consequence of millions of ‘deplorables’ turning out to vote.

In reality, there were good material reasons to want to upend the existing order; to ‘take back control’, as the pro-Brexit slogan put it – even if one disagreed with how it was done. In A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens wrote of the inevitability of the French Revolution once certain inequities were set in train. As the author put it, while the peasants were being brutally oppressed by the French aristocracy, trees ‘were growing in the forests of France and Norway that Fate had decided would one day be used to make the guillotines that would play a terrible role in history’.

This is a useful (if somewhat melodramatic) metaphor when applied to the world of today. While a generation of complacent politicians were issuing bromides about ‘progress’ and ‘globalisation’, there was a resentment building that would ultimately sweep them away. Indeed, for those who bothered to look, the makings of our populist age were discernible during the years in which politics was dominated by compromisers who wore expensive suits and churned out banal phrases like ‘forward, not back’.

Many of those who feature in the pages of this book were not part of the story that Britain (and other western democracies) told themselves after the end of the Cold War. As socialism faded away, the idea of equality was out and meritocracy was in. To be working class and proud was considered an oxymoron. You were expected to escape from the jobs that feature in this book – and to escape from the towns in which they were done. More working-class kids went to university – an escape route unavailable to previous generations – but there was less on offer for those who remained. The fact that a growing number of one’s contemporaries did manage to climb the ladder of social mobility compounded the sense of failure for those who were left behind.

The main purpose of this book was to give a sense of what it was like to work in Britain’s precarious low-pay economy. My initial aim was to take on a series of routine, poorly paid jobs, and from there to endeavour to bring to life the sights, sounds and smells of the experience for those unfamiliar with that world. I had done similar jobs myself growing up; I didn’t attend university until I was 23. Bringing the experience properly to life required that I go back, as it were, with the journalistic skills I had acquired in the intervening decade. Setting out on this journey, my main fear was not the work itself – I had done difficult and poorly remunerated roles out of necessity in the past – but rather that the jobs I would be doing would be so tedious as to invoke boredom in the reader. As it happened, things turned out rather differently.

As research for the book progressed my emphasis began to change. I had set out to write about the material poverty that often accompanies precarious work, but I quickly realised that it was just as important to write about the British towns I was living in. To work in an Amazon warehouse where you were punished for taking a day off sick was bad enough. To do so in a town with a proud residual memory of working-class trade unionism and solidarity was something altogether worse: the solidarity of the past sharpened the capriciousness that so often characterised contemporary low-paid employment. I would frequently meet people on my travels who would tell a familiar story of decline when I struck up conversation about the state of their town. There were no jobs, they told me, or the jobs that did exist were temporary and guaranteed no set number of hours each week.

The biggest employers in some of the towns where I lived were familiar household names. They had built impressive brands on the back of cheapness and lightning-fast delivery. The fact that the average customer’s experience of these companies typically went no further than a few clicks on a computer screen made it easier to ignore what went on (though there were always rumours filtering through) further up the supply chain. Moreover, much of Britain’s new working class is made up of migrant labour from Eastern Europe, making it easier still to ignore how badly many of these precarious workers were being treated. This section of the working class made a growing contribution to the British economy, yet migrant labourers were politically disenfranchised when it came to voting in general elections; the demands of the factory floor were no longer able to find expression in politics.

The sense of loss in the communities I visited was defined by more than just the disappearance of industry. When the collieries, steelworks and factories were closed by Conservative governments in the 1980s and ’90s, a culture was destroyed with them. Trade unions had once been a bulwark against unscrupulous employers, yet they were all but non-existent in the world I travelled through in 2016. This crash programme of deindustrialisation has left a toxic legacy in many parts of Britain – something that was especially true in the Welsh Valleys where I spent time working in a call centre. In the once-prosperous mining town of Ebbw Vale, five food banks were operating within an area of about 42 square miles when I arrived, while some 12 per cent of working-age residents were receiving government support for disability or incapacity – twice the national average.

Across Britain social clubs were closing at an alarming rate too: more than 2,000 have shut their doors for the final time since the mid-1970s. These clubs were not simply boozing establishments; they functioned as community centres where working-class people could retreat in the way that the upper classes did with their private members ’ clubs. They were also known to provide educational opportunities to those denied them by the formal school and college system. As the social historian Ruth Cherrington has put it, social clubs were a lot more than just beer and bingo.

Much of this probably seems unimportant to those not already steeped in such traditions. But the disappearance of the institutional affiliations that characterised working-class life for many older people is still keenly felt in parts of the country. The residual memory of such institutions, passed down to younger generations via word of mouth, heightens the sense of loss for those without access to the older collective traditions.

Elsewhere on my travels, workers were being denied access to trade unions by the ‘flexibility’ that is often celebrated uncritically by politicians. One home care worker told me about companies driving people out if they got wind of their involvement in a trade union. The company in question wouldn’t simply fire people. For one thing they couldn’t, as they could end up before an employment tribunal – but crucially they didn’t need to; for those on zero-hours contracts – almost one million people when I wrote this book – employers simply cut their hours down to nothing. Workers usually left voluntarily after that.

Of course, one has to be careful not to romanticise the industrial jobs of the past. Whenever I give a talk about my book this same point is usually made by a member of the audience – and idealising the past was never my intention when writing Hired. However, it does seem important to stress that I would find myself having the same conversations again and again as I travelled around Britain. ‘Realistically, we’re becoming poorer as a town than we were forty, fifty years ago,’ one representative conversation went in the West Midlands town of Rugeley. Few of the people I spoke to were keen to reopen the coal mines. Nor did they wistfully believe that Britain would somehow return to an economy dominated by heavy industry; you could die or suffer serious injury down the pits, after all, and many did. For all the petty humiliations on display in some of the places I worked during the research for my book, you were at least assured of returning home each night in one piece.

But many of the traditional jobs did benefit from an element of dignity and self-respect. This wasn’t handed down from on high, but rather was fought for by the workers themselves. When considering deindustrialisation in Britain, it is important to remember that this was not just one ruling party declaring war on industry – any British government, Labour or Conservative, would have eventually decommissioned loss-making pits and power stations, after all – but a full-frontal attack on the entire trade union movement. When Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher defeated the miners’ trade union, it ‘affected everyone that’s working, even up to this day,’ as it was pertinently put to me by one former collier in South Wales.

Moreover, while identity is a subject that is often talked about in today’s world, few comprehend the extent to which this is often bound up with an individual’s work – something that is especially true for men. In other words, the indignity of many contemporary low-paid jobs is about more than material poverty alone; to be poorly paid is bad enough – but to effectively be denied the right to take a toilet break (74 per cent of Amazon warehouse workers are afraid to take toilet breaks because of high productivity targets, according to the group Organise)1 is an appalling assault on a person’s sense of dignity and self-respect. Having a sense of autonomy is similarly lacking in the world of contemporary low-paid work. As dirty and dangerous as the old industrial jobs were, there was usually a trade union on hand to which you could take your grievances. The socialist movement provided a forum where you could interpret the world and try to change it. One could be working class and take action against the system, not simply be acted on by its mysterious market forces.

The loss of these isles of working-class democracy has repercussions far beyond the factory gates and the pages of this book. Political life today is increasingly characterised by conspiratorial thinking. Noisy online hot-air merchants attribute the invisible power of capitalism to everyone from bankers to Jews to the CIA. A receptive audience for this stuff is growing. People are angry with a system that they don’t believe is delivering for them and their families, and on my own journey around Britain it was often migrants and those claiming social security who were singled out as targets for local anger. Without the democratic movements through which ordinary people can take a stand collectively, it doesn’t take long for scapegoats to then be found and blamed for the ruptures inherent in the capitalist system.

Some of the more pleasing responses to the book have been from those who aren’t naturally sympathetic to left-wing ideas. Many people have reached out to me since it came out to say that Hired opened their eyes to how people were being treated at the lower end of the labour market. We may have gone on to disagree about potential political solutions, but there was usually consensus that something has gone badly wrong in our society for people to be treated in this way.

One of the recurring themes of my book is the destruction of working-class communities in Britain. There seems to be a growing awareness across the political spectrum that the established employment market is not always the guarantor of the good life.

Hired has had a more obvious impact in drawing attention to the way in which Amazon warehouse workers are treated by the company. As the Economist magazine put it in September 2018, ‘A detail provided by James Bloodworth, a British journalist who went undercover in an Amazon facility and says he encountered bottles of urine from employees too scared to take bathroom breaks, has proven particularly difficult for the company to shake.’2 In 2018 I was asked by American Democratic senator Bernie Sanders to feature in several short videos to talk about my time working undercover at Amazon. The GMB trade union have also stepped up their campaign to highlight some of the grievances Amazon workers have been facing when toiling away in the company’s warehouses. (This included an investigation which found that hundreds of ambulances had been called out 600 times to 14 Amazon warehouses in three years.)3

Ultimately, the pressure we put on Amazon and its billionaire founder Jeff Bezos (who has gone on to become the wealthiest individual in the world since Hired came out) resulted in the company pledging to increase the minimum wage it was paying its warehouse staff in the UK and the US4. The company said it would increase its US minimum wage to $15 an hour for more than 350,000 workers. In the UK, 40,000 workers will get a rise to £10.50 an hour in London and £9.50 an hour in the rest of the country. Bezos – thought to be worth in excess of $150 billion – has also pledged to create a $2 billion (£1.5 billion) ‘Day One Fund’ to pay for a network of pre-schools and help tackle homelessness in America.

The fact that these moves came after years of drip-drip stories about conditions in Amazon’s warehouses lends weight to the argument that the move was little more than a PR exercise on Bezos’s part. Indeed, contained in the announcement on the increased minimum wage, Amazon revealed that its warehouse workers would no longer be eligible for monthly bonuses and stock awards.5 According to the Guardian, the change could actually see some workers making less money over the long term. Other attempts by the company to dispel the negative image of its warehouses have included employing company ‘ambassadors’ who reply on Twitter to allegations of poor treatment.

As anyone familiar with the revelations contained in Hired will understand, the problems at Amazon go beyond just money. There were the feats of physical endurance expected of Amazon warehouse workers who had minimal break time. We walked up to 15 miles a day with half an hour for lunch and two ten-minute breaks. Because of the size of the warehouse and the time it took to reach the canteen, breaks were in reality much shorter than this. And then there were the productivity targets that forced workers to run in order to keep their jobs, despite there being a prohibition on running (for which you could also lose your job). There were the numerous instances of ambulances being called to Amazon’s warehouses because workers were afraid to take time off sick. It was fear of missing productivity targets that almost certainly explained why I did indeed find a bottle of urine on a shelf in Amazon’s Rugeley warehouse three years ago. When I travelled back to Rugeley in June 2018, several workers I spoke with told me that productivity targets were even higher than they had been when I had left.

For its part, Amazon has claimed that it no longer punishes workers with disciplinary points when they take days off because of illness. If true, this is a welcome move. However, it is impossible to really know whether the improvements Amazon claim to have made are as significant as the company wishes to make out. Before I did my undercover stint in 2016, Amazon claimed that its sickness policy – the same policy I worked under, which saw workers handed disciplinaries for taking days off, even with a doctor’s note – was ‘fair and predictable’.6 I’ll let readers make their own minds up on that score.

Since Hired ’s publication in 2018, Amazon has claimed that I deliberately set out ‘to create negative content’ for my book and that I did this for my own ‘personal profit’. As almost any writer will know, few of us are ever likely to make much real money from publishing our work. That isn’t why we do it. Nor did I deliberately try to besmirch Amazon’s reputation. Indeed, it was sheer happenstance that I ended up working for Amazon at all: I stumbled across an online advert by the employment agency Transline (one of the agencies Amazon used to recruit workers in 2016) as I was looking for my first job. I applied and I got it. I believe I treated all of the companies I worked for in a fair way. This ought to be obvious from the compliments I pay to the car insurance company Admiral in the book, in particular for what I believed were its genuine attempts to create a pleasant working environment for its staff. Moreover, I am a journalist as opposed to a political activist, and the truth is more important to me than any party line, ideology or ‘ism’.

Hired is about more than just Amazon, though. It is about how we treat people who do the jobs the rest of us often aren’t prepared to do. These are jobs that are fundamental to our own security and comfort. Those who are lucky enough to live to old age will at some point require social care. Almost everyone reading this book will have ordered something from Amazon. We’ve all spoken on the phone with people who work in call centres, while those of us who live in big cities will probably have taken an Uber taxi or have had something delivered by bicycle courier. Hired is a book about the most precarious parts of Britain’s twenty-first century economy and the new working class that toils away there. Much of what we like to call civilization – with all its consumer comforts – depends on the sweat of the people who feature in the pages of this book. The contemporary consumer experience may be several degrees of separation from the supply chain – who thinks about what goes on in an Amazon warehouse when they click an order through on a computer screen? – but the fundamental divide remains the same. There are those who own things in our society, and there are those who have little to sell but their own labour.

Hired is a book about the hidden underbelly of the British economy in the twenty-first century. It is also a book about the sorts of people who are seldom acknowledged by politicians or the media. They are not heroes or villains. Indeed, they are usually no different from you or me.

Yet for some reason we find it acceptable to treat them like this.

James Bloodworth, November 2018

___

INTRODUCTION

Early in 2016, as the sun crept out from behind the clouds and the bitter winter frosts began to subside, I left London in a beaten-up old car to explore a side of life that is usually hidden from view.

Around one in twenty people in Britain today live on the minimum wage. Many of these people live in towns and cities that were once thriving centres of industry and manufacturing. Many were born there and an increasing number were born abroad.

I decided that the best way to find out about low-paid work in Britain today would be to become a part of that world myself: to sink down and become another cog in the vast, amorphous and impersonal machine on which much of Britain’s prosperity is built. I would penetrate the agencies that failed to pay their staff a living wage. I would live among the men and women who scratched a living on the margins of a prosperous society that had supposedly gone back to work after a long, drawn-out recession. And I would join the growing army of people for whom the idea of a stable, fulfilling job was about as attainable as lifting an Oscar or the Ballon d’Or.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008, ‘austerity’ became the raison d’être of the British government. There was ‘no money left’ – so it was confidently proclaimed – and public services had to be cut back drastically or else contracted out to private companies who supposedly knew better how to run them than the state.

Since then the mood music has grown more optimistic: Britain is enjoying record levels of employment. Yet sunny optimism about the labour market masks the changing nature of the contemporary economy. More people are in work, but an increasing proportion of this work is poorly paid, precarious and without regular hours. Wages have been failing to keep pace with inflation. A million more people have become self-employed since the financial crisis, many of them working in the so-called ‘gig’ economy with few basic workers’ rights. Toiling away for five hours a week may keep you off the government’s unemployment figures, but it is not necessarily sufficient to pay the rent. Even for those in full-time work the picture is hardly rosy: Britain has recently experienced the longest period of wage stagnation for 150 years.

I set out to write about the changing nature of work, but this is also a book about the changing nature of Britain. Half a century ago Arthur Seaton, the anti-hero of Alan Sillitoe’s cult novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, may have hated his dull job as a lathe worker in a Nottingham factory, but he could at least take a day off now and then when he was ill. There was a union rep on hand to listen to his grievances if the boss was in his ear. If he did get the sack he could usually walk into another job without too much fuss. There were local pubs and clubs at which to drink and socialise after work. All in all, there was a definite sense that, while the struggle between bosses and workers was not at an end, there had been a fundamental change in its terms.

The social democratic era probably ended in 1984, when the police batons came crashing down onto the heads of working men whom the former Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had once described as ‘the best men in the world, who beat the Kaiser’s and Hitler’s armies and never gave in’. The stunned faces of the miners, knocked for six by the police and plastered luridly across the tabloids, seemed to capture the realisation of the time that, after a brief interregnum, to be a working man or woman was once again to be, if not despised, then only just tolerated.

Life in Britain has improved a great deal for many over the past forty years. Unthinking nostalgia is a dead end, the equivalent of an attempt to reside in the ruins of a crumbling old house that is full of cobwebs and on the verge of collapse. A sepia-tinged yearning for the mid-twentieth century is especially insulting to those for whom the century of the ‘common man’ was just that: the century of the white, heterosexual man. We live in a time that is both richer and more free than the era of hanging and the Notting Hill race riots.

But as our world of liberal progress was being built, another world was being dismantled. The mines are gone but so, almost, are the trade unions, reduced to rump organisations largely confined to the public sector. Were Arthur Seaton alive today, he would conceivably be trapped on a zero-hours contract in a dingy warehouse, cowed, fearful and forever trying to slip off for a two-minute toilet break out of sight of a haughty middle manager. Or maybe he would have gone on to university – a prospect quite unthinkable for most working-class young men and women when the novel that made him famous was first published in 1958.

A book about work is inevitably a book about class. Each generation we tell ourselves that class is dead, yet with every generation we fail to dispose of the cadaver. Those who lose their footing and slip down the social order very often sink into poverty; but even today a relegation to the lower depths of the social hierarchy can invite onto one’s head a class hatred that burns every bit as painfully as economic dislocation.

I would not claim that what follows is an original or pioneering way of reporting on working-class life. Nor did I set out with the intention of confirming my already-existing prejudices. I did not know what to expect on my travels. It would be more truthful to say that I went into the project with an open mind and was to some extent radicalised by the process. Many of the things I found were worse than anything I had expected to see in one of the richest countries in the world.

But then, pick up almost any newspaper in Britain today and the message leaps off the page at you: poor people are the way they are because of their moral laxity or their irresponsible life choices. The old Victorian attitude still prevails. As Henry Mayhew subtitled the fourth volume of his epic nineteenth-century documentary on London, there are: Those that will work, those that cannot work, and those that will not work.

Neat divisions of this sort are as illusory today as they were when Queen Victoria was on the throne: an era when pseudo-scientific theories of class put people in the workhouse at home and threatened them with a bayonet in the guts abroad. The gap between comfortable prosperity and miserable squalor is not always as vast as many would like to believe. It is easy enough to sink down into poverty in modern Britain, and it can happen regardless of the choices you make along the way.

I do not claim that my going undercover was the same as experiencing these things out of necessity. Ultimately, I was a tourist. If things got too bad I could always draw on money in the bank or beat a hasty retreat back to a more comfortable existence. But my aim was never to get drawn into an ego-driven squabble over the ‘authenticity’ of my approach. I simply decided that going undercover would be the most effective way of learning about low-paid work, and I still believe that to be true.

I will, of course, be denounced by some for writing this book at all. A healthy fear of paternalism can occasionally be replaced among well-meaning people with a blanket lionisation of ‘authenticity’. Many would undoubtedly have preferred that I deferred the task of writing this book to an ‘authentic working-class voice’. This desire to hand working people the pen or the microphone is an admirable impulse in its own right; yet it can lead to quietism if treated as an absolute. Few of the people I would meet on my journey had the time to pontificate in the Guardian about their lifestyle. One of the reasons there are so few working-class authors today is precisely because a working-class job is typically incompatible with the sort of existence required to dash off books and articles. At a very basic level, a prerequisite to sitting down to quietly turn out 80,000 words is not having to worry about the electric being turned off or the discomfort of an empty stomach. There are many factors that can obstruct the paths of working-class authors. The existence of this book is probably not one of them. Any movement that seeks to change those circumstances will also have to bring a significant section of the middle classes along with it if it is to succeed. I believe that books like this one are a more effective way of doing that than yet another hair-splitting pamphlet preaching to the already converted.

And besides, if it matters, I was doing precisely the sorts of jobs that appear in this book well into my early twenties. I was born to a single mother in Bridgwater, Somerset. I left school with few qualifications; after various arduous retakes I was the only one of four children to study at university. This book is less an exercise in ‘slumming it’, and more a return visit to a world I narrowly escaped.

As for what I have sought to avoid, I did not want to write another dry and turgid tome about ‘austerity’ or ‘the poor’. There are enough books of that sort already. I wanted instead to experience at least some of the hardship myself, and to write a book that contained real human beings rather than unusually saintly or malevolent caricatures. The media landscape is already soaked with the opinions of company directors, managers, bureaucrats and the orthodoxies of one political hue or another. Thus I have approached the worker and the man or woman who sleeps in the street with my questions, rather than the boss or the academic with a theory purporting to explain why they sleep there. Ultimately, I wanted to see things for myself rather than read about them second-hand in books and newspaper articles written by those who had never really looked.

In terms of the practicalities, when I set out on my journey I had in my hand a scrap of paper with a rough plan scrawled upon it: I would spend six months taking whatever minimum-wage jobs I was offered. The aim was not to travel to every part of the country, but nor did I want to stay too firmly rooted in one spot. Outside of London I would look for work in the sort of towns that rarely interest governments or the media unless there is an election in the offing. I did not begin with a plan to go to anywhere in particular; I simply went where I was offered a job and when I got there I lived, where possible, on the salary I was paid. The only people who knew what I was up to were those I sat down with and interviewed along the way. In those instances, I stepped temporarily out of my adopted persona and became once again a writer. Had any of my employers ever got wind of what I was up to they would undoubtedly have fobbed me off with some PR dogsbody, which is what happened whenever I tried to speak to an organisation openly. I was tired of people telling me things they knew to be untrue simply because they had been paid to say them.

Politically speaking, a lot has happened since I first set out to write the book. One government has fallen and another has taken its place. The present Conservative regime clings on but only just. The Labour Party has moved to the left and, for the first time in a generation, there is a whiff of socialism in the air. All of this – together with the ascendancy of a mercurial American President – has ignited a renewed interest in the plight of the so-called ‘left behind’ and others thought to be feeling disenfranchised by globalisation. This sympathetic mood may pass soon enough. But when it does, the resentments will linger on: there is much to be in disgust about, and it takes a certain type of comfort and affluence not to see it.

Ultimately this is a book about working-class life in the twenty-first century. It is an attempt at a documentary about how work for many people has gone from being a source of pride to a relentless and dehumanising assault on their dignity. This is a series of snapshots rather than a comprehensive study. I could not go everywhere and work for everyone, but I do not feel that anything in these pages is particularly exceptional. I am certain that someone reading this book could go out and find similar things for themselves, which in a way makes what follows even more disconcerting.

PART I

___

RUGELEY

___

1

It was quarter past six in the evening and the siren had just sounded for lunch: a loud noise pumped through loudspeakers into every corner of the cold and drab warehouse. It sounded like a cheap musical doorbell, or a grotesque parody of the tune a plastic ballerina plays as she slowly spins on top of a jewellery box.

While I stood in the queue, hands in pockets, waiting to get out, a well-built security guard darted forward and made a signal for me to put my arms in the air. ‘Move forward, mate, I haven’t got all afternoon,’ he said firmly in a broad West Midlands accent. I moved along and received a brisk pat-down from the guard. I was followed by a long undulating line of around thirty exhausted-looking men and women of mostly Eastern European nationalities who were shuffling through the security scanners as fast as the three guards could process them. We were in too much of a hurry to talk. We were also emptying pockets and tearing off various items of clothing that were liable to set off the temperamental metal detectors – a belt, a watch or even a sticky cough sweet clinging limply to the inside of a trouser pocket.

There was some sort of commotion at the front of the line: a quarrel had suddenly erupted between a security guard and a haggard-looking young Romanian man over the presence of a mobile phone. We all looked on in befuddled silence.

Security guard: You know you’re not supposed to bring those in here. You were told that on your first day.

Romanian: I have to wait for important call. My landlord want to speak with me.

Security guard: Why can’t you make personal calls in your own time like everybody else? For the umpteenth time, I’ll tell you again. No ... mobile ... phones ...in ... here! Do you understand me? Now, I’ll have to tell your manager.1

The place had the atmosphere of what I imagined a prison would feel like. Most of the rules were concerned with petty theft. You had to pass in and out of gigantic airport-style security gates at the end of every shift and each time you went on a break or needed to use the toilet. It could take ten or fifteen minutes to pass through these huge metal scanners. You were never paid for the time you spent waiting to have your pockets checked. Hooded tops were banned in the warehouse and so were sunglasses. ‘We might need to see your eyes in case you’ve had too much to drink the night before,’ a large, red- and waxy-faced woman named Vicky had warned us ominously on the first day. ‘Your eyes give you away.’2

For hour after sweating hour we had traipsed up and down this enormous warehouse – the size of ten football pitches – tucked away in the Staffordshire countryside. Each day this short break came as temporary relief.

Lunch – we still called it lunch despite it being dished out at six o’clock in the evening – marked the halfway point in a ten-and-a-half-hour shift. After going through the usual rigmarole of security, the men and women would spill into the large dining hall and fan out in every direction like an army of ants in flight from the nest. Most of us rushed headlong into the hall to grab a tray and establish a respectable position in the lunch queue. The whole panicked dash was punctuated by a chorus of yells and fiery laments. The best of the hot food had usually gone by the time the first twenty or so men and women had hurriedly passed through the canteen. It was therefore of great importance to secure a spot in the queue as quickly as possible, even if it meant shoving one of your co-workers out of the way in order to do so. Solidarity and the brotherhood of man did not exist in this world. You trampled on the other guy before he walked over you. If you were that sorry unkempt Romanian who had fallen foul of security – yelled at incoherently in a language you barely understood – you might be waiting six or seven hours before you got to see another inviting plate of mincemeat soaked in gravy and stodgy carbohydrates.

Eastern European languages filled the air of the shiny-floored dining hall, which was brightly lit like an operating theatre and always smelt strongly of disinfectant. There were around fifty men and women perched at the canteen tables, hunched over little black lunch trays furtively shovelling huge dollops of meat and fistfuls of chips into their mouths. The Romanians would always unfailingly clean up after themselves. They were, in fact, the most fastidious workers I had ever come across. Along with those of us who sat at the tables, another ten or so men stood milling around next to the coffee machines – head to toe in sportswear, hands in pockets and surreptitiously following every woman who shimmied past with leering eyes. On the opposite side of the dining hall was a huge window which looked out onto the big grey cooling towers of the local power station. ‘Proper work,’ you would think as you gazed up at the vast chimneys that puked white clouds of steam into the sky as jackdaws glided round and round like burnt pieces of paper.

One of the perks of the job was the relatively cheap food and the free teas and coffees available from the many vending machines. Mincemeat, potatoes or greasy chips plus a can of drink and a Mars bar for £4.10 – not a great deal more than the cost of preparing food beforehand, and most of it piping hot, unlike sandwiches made at home. The challenge was finding sufficient time to eat and drink during the short window allocated for break. I could count on one hand the number of times I managed to finish a full cup of tea.

We were allocated half an hour for lunch, but in practice spent only around half of that in a state of anything resembling relaxation. By the time you made it to the canteen and elbowed your way through a throng of ravenous workers, you had around fifteen minutes to bolt down the food before you started the long walk back to the warehouse. Two or three English managers would invariably be waiting for you back at the work station, pointing at imaginary watches and bellowing peremptorily at anyone who returned even thirty seconds late: ‘Extended lunch break today, is it?’ ‘We don’t pay you to sit around jabbering.’3