20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

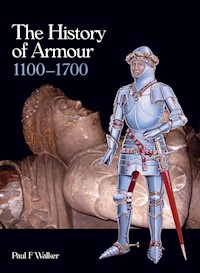

The History of Armour 1100 - 1700 offers a detailed account of how armour developed through the Medieval, Tudor, Elizabethan and Civil War eras, carefully itemizing the subtle changes over a six hundred year period. Each chapter focuses on an individual area of body protection, charting the evolution of each piece over time, from helmets and chest protection to arm guards, gauntlets, leg guards and sabatons. The book also encompasses the use of weaponry and its evolution, including protection for the horse.With the aid of the author's superb photographs and illustrations, the book looks at how fashions, as well as its protective qualities, influenced the style of armour. Valuable information has been acquired through the study of effigies over a number of years, and using these existing artifacts, supplemented by the author's meticulous illustrations and practical knowlege of armour construction, it has been possible to reconstruct the design and appearance of a wide range of armour. A meticulous study of the development of the knight's protective armour and weaponry over a six hundred year period. Through the study of effigies over a number of years, the author has been able to reconstruct the design of a wide range of armour. An invaluable resource for historians, re-enactors, collectors and all those with an interest in miltiary or medieval history. Superbly illustrated with 275 colour photographs and illustrations. Paul Walker gives lectures in armour and weapons for English Heritage and has a lifelong interest in historical warfare.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 228

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

(a)Helmet (b)Visor (c)Gardbrace (d)Rerebrace/Uppercannon (e)Vambrace/Lowercannon (f )Gauntlet (g)Cuisse (h)Poleyn (i)Greave (j)Sabaton (k)Tasset (l)Fauld (m)Couter (n)Pauldron (o)Breastplate (p)Mail skirt.

Copyright

First published in 2013 by The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book edition first published in 2013

© Paul F. Walker 2013

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 1 84797 515 7

Dedication For my wife Karen who persistently badgered me to get the thing finished so that she could have her laptop back.

Acknowledgments Thanks must go to the many churches that enabled me to photograph their wonderful effigies and sculptures; I have made every effort to name throughout this book those monuments used and the churches that they are situated in. Also to the local historians, re-enactors and friends whose knowledge of their individual subjects and kind help aided the completion of this book.

The author wearing a modern copy of a typical harness from around 1415. Note the narrow sword belt and broad hip belt with decorative gilt plates. (Author’s collection)

Contents

Introduction

The knight in shining armour conjures up one of the most evocative images of the medieval period. Between the eleventh and seventeenth centuries, the nobility made their mark on Europe – they ruled the population, its economics, life-style, fashions and history. Great books were written for the wealthy, large houses and castles were built, sonnets were written and ballads were sung. They displayed their wealth and strength, which often meant the male’s role in battle and his ability to fight and protect his land and himself. This need to be protected in battle quickly gave rise to the development of armour, essentially an external ‘skin’ that covered the body, starting with leather and mail and developing over a period into the metal-clad knight so familiar in children’s books and films.

The development of medieval, Tudor and English Civil War armour, and the way it changed during the 600 years it was used, has been studied and examined by many experts over the years. Re-enactment groups and modern armourers have helped to gain an understanding in the practicalities of constructing and wearing of armour. Many books have been written about armour, but few have concentrated on one of the most important, accurate and contemporary resources, the effigy.

In this book, I will attempt to give an account of the changes of armour. Looking at details that make a suit of armour, from the methods of construction to the way it was worn and the way fashion dictated changes in armour design. It is hoped that this book will enlighten students of arms and armour and give an insight to the art of the effigy-maker, showing the skill they possessed by reproducing the armour and weaponry of their period in wood, stone and metal.

As an art form, the effigy has given us the ability to look into the past and view the development of armour and its changes through the ages; however, we must acknowledge that these representations may not always give us an altogether accurate picture. The effects of damage, especially during the iconoclasm of the English Reformation and during the Civil War when some of these precious relics were mutilated (some beyond repair), also the ravages of decay and even misrepresentation through stylized sculpting, plus poor restoration, must all be considered when assessing the accuracy of the armour on each effigy.

The most rewarding aspect of my research has been the visual reconstruction of damaged effigies via my illustrations. I admit that the paintings are purely conjectural and other better-qualified scholars may have different ideas, nevertheless I have tried to be faithful to the details that remain on each effigy, whilst using known armour designs to enhance any missing areas.

Effigy of Fulke de Pembrugge, d.1409.

Chapter 1

Development of Armour

The development of armour begins in pre-history, but we need not worry ourselves with the beginnings but rather we should concentrate on the conception of the knight in the eleventh century. If we look at the tapestry that commemorated 1066, a year that changed the history of England, we will see a collection of images that represent men-at-arms dressed in mail coats with conical helmets and long, kite-shaped shields. Some have mail leggings, whilst many have no armour at all, but these stylized images show how men dressed for war in the eleventh century (see figure A).

Mail changed little throughout the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries, with the exception of minor details. The shape of the helmet changed from the typical Norman conical shape to the rounded skullcap and then to the cylindrical-shaped helm. Metal knee protection appeared in the early thirteenth century and the shield decreased in size, but overall the main form of defence remained mail (see figures B and C).

In the early fourteenth century, something happened that would start an arms race that lasted three hundred years – the capability of producing large quantities of iron and steel. Moreover, it is from this period that the armourer begins to develop the methods of plate armour production (see figure D).

Armour design. A, eleventh-century knight. B, Early twelfth-century knight. C, Mid-thirteenth-century knight. D, Early fourteenth century knight.

The modern fighting soldier’s idea of warfare has no bearing on the medieval knight’s ideal. Warfare had its political and social reasons, just as today, but the social élite could use warfare as an income and a means of elevating their status. The capture and ransoming of a wealthy knight might ensure he survived a battle; thus, the ability to show ones wealth in battle became important.

The knight not only needed armour as a form of physical protection, but also needed it to convey his wealth and standing. Thus, the development of armour changed from a purely defensive matter and moved into the realm of visual display. The knight became a deadly peacock, using the bright colours of heraldry to distinguish each other on the battlefield and in tournament.

Heraldry had arisen in the eleventh century with simple patterns, designs and pictures, and over a 500-year period would develop into a complex method of recognizing individuals and families. The main areas on a knight that displayed heraldic arms were the shield, the surcoat and the crest. In most circumstances the crest is the only surviving clue to the heraldic design of an individual that can be found on an effigy, this being part of the headrest. In some cases, the shield and jupon have a coat-of-arms carved into them, some even retaining the original colours.

Armour design. E, Mid fourteenth-century knight. F, Late fourteenth-century knight. G, Early fifteenth-century knight. H, Late fifteenth-century knight.

During the early fourteenth century, plate protection was added to mail armour, arm and leg protection being strapped on to mail. The surcoat was shortened at the front becoming the cyclas. The knight wore a padded aketon underneath his mail coat or haubergeon; above this, a coat of plates may have been worn (see figure E).

By the mid-fourteenth century, plate protection had superseded mail on the arms. On legs, plate was used but often took the form of studded leather and metal splints. The surcoat had been replaced by the much shorter and tighter jupon (see figure F). A horizontal belt with plaquarts plus gilded edging was now added to the harness, and the basinet and aventail became universally used throughout Europe.

The early fifteenth century saw the development of the great basinet with its gorget, and the first full plate suits of armour appear. The average thickness of the steel used was around 1.5mm but certain areas, such as the breastplate or helmet, could be made thicker (see figure G).

By the late fifteenth century, the intricate gothic styles in German armour increased (see figure H), but in England, the plainer Italian style was preferred. However, the sallet eventually took over from the great basinet.

Armour design. I, early sixteenth century knight. J, late sixteenth-century knight. K, early seventeenth century heavy cavalry officer. L, early to mid-seventeenth century officer.

During the early Tudor period, Italian-style armour with plain surfaces (see figure I) appears on many effigies. In reality, the use of heavily fluted armour (later to be called Maximilian) was used throughout Europe. The development of the close-helmet, which hid the head completely, meant that the effigy-maker often replaced the traditional helm as headrest with this form of helmet.

The Elizabethan period saw the development of increased articulated lames, heat-treated coloured metal and elaborate decoration. The joust became the showpiece for armour, with knights displaying their wealth through highly decorated garnitures, designed to have interchanging parts for different forms of tournament. Added pieces, some being up to 3mm thick, were used to reinforce original suits (see figure J).

During the seventeenth century, the development of heavier, thicker plates to stop the round shot from guns meant that armour became utilitarian and plain (see figure K). The idea of knighthood did not disappear and elaborate harnesses, which had no place on the battlefield, were produced for the new officer class (see figure L).

Chapter 2

Effigies

The effigies that can be found all around Britain and Europe show a diverse range of sculptural methods, colour application and metalwork skills, but most importantly, as far as this book is concerned, they show the changing designs of armour.

The effigy-makers across Europe left some of the best insights into the world of armour construction, and in this book I will be looking at the individual sections of armour represented, such as the helmet, the gauntlet and so on, in chronological order, beginning in the twelfth century and ending in the seventeenth century.

The development of the effigy began in the twelfth century with simple carved coffin lids. Some of these had an image of the deceased in armour carved into it. These lids were often simple in design but examples exist into the fourteenth century. Over time, the skill of the stonemason, or more accurately the ‘kerver’, to portray armour improved and more elaborate, three-dimensional representations of armour were reproduced in stone.

Oak effigies, such as the one found at Berrington in Shropshire, were carefully carved out, and then painstakingly covered with layers of gesso until a smooth, white surface was achieved. This surface was then incised with the patterns of mail and coats-of-arms, so that a realistic impression was made. Finally, the effigy was decorated with coloured pigments mixed with egg tempera and a lifelike representation of the deceased was achieved.

In the Midlands, the hub of monumental effigy-making was Nottingham. Famous for its alablastermen, as they were known, it produced effigies that supplied Britain for almost 400 years. Other centres, such as Chellaston in Derbyshire, were fortunate to have alabaster quarries close to hand and Nottingham obtained this easily carved material from such quarries. The alabaster would be quarried and cut into large blocks, transported by horse and cart to the river and then shipped to Nottingham by barge.

At the workshop, the alablastermen, who were also known as kervers or image-makers, would dress the stone and mark the shape of the effigy on the surface. The stone when first cut is soft and easy to carve into; as time passes and the stone is exposed to light and air it hardens, thus making it an ideal medium for sculpting. The stone would be chipped or filed away with specialist chisels and blocks until the main shape of the effigy was made. The stone would then be polished by hand until the surface was smooth. The effigy was then ready to be gilded and painted, giving the effigy an almost lifelike appearance.

Some of the earliest alabaster effigies appear in the thirteenth century, Sir John de Hanbury at St Werburgh’s Church, Hanbury being one of them. By the fifteenth century, the alablastermen in Nottingham and Tutbury were selling their monuments as far as France, such was the quality of their work.

Between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries the effigial monument reached its pinnacle with carvings of the deceased’s children, heraldic shields, angels and saints, all placed around the base of the monument. Stone canopies above the tomb became popular and in some cases looked almost like miniature cathedrals, with richly carved ornaments and spires; many monuments were painted with realistic colours.

Nottingham workshops with alabastermen or kervers at work.

Bronze or lattern effigies, such as the one in Canterbury of Edward (The Black Prince) and that at Warwick of Richard Beauchamp, were carefully cast in sections. These amazing works of art provide some of the best details of armour construction, showing straps, rivets and hinges, and must have used actual pieces of armour to obtain the moulds.

As armour changed, so did the effigy. Many fashion changes are shown and the stylistic features can be seen in the carving. However, there are periods when the effigy-maker is left to his own devices and generic patterns are used to carve from rather than actual armour. The Tudor period gives us some fantastic effigies that are sculpted from patterns, the carver using all of his artistic imagination to make a wonderful sculpture but to the detriment of the authenticity of armour design. During the Elizabethan period, the effigy-maker placed his figures in naturalistic poses, sometimes represented lying to one side whilst resting on an arm, or kneeling in prayer.

Reconstruction of early fifteenth-century painted effigies.

Reconstruction of mid-fifteenth-century painted effigy.

Early fifteenth-century effigy as it would appear when first painted.

Eventually, in the seventeenth century, armour would play a lesser role in the field of warfare and the effigy that displayed a knight in armour would give way to the sculpture or painting of ‘the gentleman officer’. The effigy-maker’s skill would carry on long after the armourer’s demise but the representation of military costume would no longer be needed in the same way.

The effigy-maker has provided us not only with some of the most beautiful sculpture of armour spanning almost five centuries, but also an insight to the methods used in armour construction, the way it was worn and the changing fashions of military wear.

The effigy is the only surviving three-dimensional contemporary reference that anyone can go and see without the need to enter a museum or peer behind a glass case to study. Its use as a reference for students of warfare, modern-day armourer and re-enactors is invaluable and second only to those rare examples of surviving real armour that are scattered around the country in museums and private collections.

Finally, I would like to quote from F.H. Crossley’s book English Church Craftsmanship (Batsford, 1941):

If a number of English folk are, as a result, enabled to appreciate something of their national heritage in church craftsmanship, and will take the trouble to seek it out and help preserve it, our intention will have been achieved.

Effigies from Greystoke in Cumbria.

Chapter 3

The Knight

The origin of the word ‘knight’ derives from many sources, in old English it is cniht meaning boy or servant. The English word had its origin in the Germanic countries being knecht, which also meant servant or, more accurately, bondsman. During the Anglo-Saxon period, the name for any horse-riding messenger or servant was radcniht. The key meaning of the word seems to revolve around the idea of a servant, which over a period of time becomes a servant that rides a horse.

By the early medieval period, all male horse-riders could be described as a knight. This should not be seen as unusual, as those who could afford to equip themselves to ride would have had some status already. Those riders who were servants would have been expected to protect whoever equipped them and as such would be seen as mounted soldiers or men-at-arms, even if this was not their profession.

By the twelfth century, the definition of knighthood became intrinsically connected with social rank. The inception of the idea of a highborn, fighting man that gave loyalty and military service to his lord and king was born. Even though knighthood was open to all young men, the financial expenditure involved in obtaining the most rudimentary of equipment meant that only those with a good income could expect to succeed. The prospective knight was trained from an early age to use weapons and to ride. The young squire was also schooled in the arts of dancing, reading and writing, and most importantly the concept of being courteous.

The French word chevalier, meaning one who is skilled in handling a horse, would be adapted and used to describe those who understood the intrinsic meaning of being a knight and all that it entailed, and the word chivalry would come to describe the concept of what a knight should be.

The knight’s role inevitably placed him in the forefront of warfare. Skills in swordplay and lance control were taught and tournaments became the training grounds of the knight. Early tournaments in the eleventh and twelfth centuries were nothing more than small-scale battles with very few rules; villages could be wrecked in the melée and knights could even be killed. Eventually the tournament would become organized with rules and a grading system that gave the knight a league table that would be recognized across Europe; knights could gain vast wealth and status from the joust.

In warfare, the knight was equipped with state-of-the-art equipment; every change and improvement in the arms race was met with a counteractive development of protective clothing. Armour was expensive and many young, prospective knights would need to either gain money from tournaments or capture armour in battle.

Those knights from high-status families would be expected to lead and command in battles, and the military teachings of the ancient Greeks and Roman commanders became key learning for the medieval warlord.

The concept of knighthood was intertwined with religious beliefs and with the advent of the crusades, religious orders of knighthood began to appear for the first time. In the eleventh century, one of the earliest orders – the Knights Hospitallers – was founded during the First Crusade in 1099, the Order of Saint Lazarus was established about 1100 and the Knights Templars was founded 1118.

Other religious orders were established throughout the crusades but during the fourteenth century, chivalric orders were influenced by the romantic ideals of mythological tales, such as the Odyssey and the Arthurian romances. The Order of Saint George was founded by Charles I of Hungary in 1325–26, the Order of the Garter, founded by Edward III of England, around 1348 and the Order of the Golden Fleece, was founded by Philip III, Duke of Burgundy in 1430.

The chivalric code that was to become important to the knight would usually extend only to others of a similar status, and in battle the knight would be expected to adhere to the code. Of course, this was not always the case and the idea of a battle where knights could yield and be escorted off the field should remain in the romantic novels of the time. Having said this, those knights with rich families would be more useful captured and ransomed, and those knights looking to upgrade equipment and status might seek out the better-dressed opponent. Unfortunately, for most men-at-arms the horror of warfare was all too real and after a battle the field was scoured for armour and weapons to either upgrade or sell.

By the seventeenth century, the idea of knights being the vanguard in battle became redundant and the concept of organized troops placed those wealthy enough in command of large companies of men.

The concept of knighthood did not die with the knight, neither did chivalry, but the need for the knight to train in the martial arts would no longer be needed. Training in horsemanship and swordplay would still be important in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, until the mechanized warfare of the First World War made it redundant. Even so, the symbolic use of the sword by the officer class is still in use and the breastplate, steel helmet and thick leather boots are still worn by the mounted lifeguards, which can be seen in London today.

Men at arms from the Wars of the Roses.

Chapter 4

Head Protection

The helmet as a form of protection dates to pre-history but for our purpose, we will begin at the inception of the knight in the eleventh century.

The conical-shaped helmet used during the eleventh century was formed from a series of four triangular plates beaten into a curved, bowl shape and joined via rivets on metal strips. With the development of iron production, a larger single plate could be beaten out to form a pointed skull shape. This method of making the skull of a helmet changed little in the following six centuries, but the shape and design would change dramatically. A tight-fitting, pointed helmet of the Norman period would make way for the more rounded skullcap during the twelfth century. Domed helmets with gilded circlets fixed to them can be seen in the French mid-thirteenth century Maciejowski Bible. This tight-fitting helmet would eventually be covered by a looser barrel-shaped helm that surrounded the head. The domed helm became popular being better than the more common, flat-topped helm for deflecting blows. Similar helms can be seen in illustrated manuscripts from the period and also monumental brasses, such as the one belonging to Sir Roger Trumpington in Cambridgeshire. The helm itself would change and develop and would eventually branch away from warfare to be used only in the tournament.

In the fourteenth century, the basinet with its pointed visor served to protect the face, side and back of the head. Elaborate methods of covering the neck and shoulders, beginning with mail, would be designed and re-designed as the arms race accelerated. The thickness of plate armour depends on three main factors: weight, flexibility and strength. Most armour throughout its development has had a thickness between 1mm and 2.5mm; this thickness depending on the need for protection.

Helmets and breastplates would have required thicker areas than say sabatons, which protected the foot. With the development of steel production and the ability to harden metals through heat treatment, armour became more effective. Eventually, in the fifteenth century, the sallet, a loose-fitting helmet similar in design to a modern soldier’s helmet, and the armet, a tight overall helmet, would outmode the basinet.

Throughout the sixteenth century the close helm was used but primarily as a tournament helmet. The fighting knight was giving way to the more modern idea of rank and file, and as such the need for overall protection was no longer needed. The soldier now used either the morion, a rounded, open-faced helmet that had a brim and high comb, or the burgonet, a helmet that extended down the back of the neck and had hinged cheek-pieces. Finally, during the seventeenth century, the close helm, morion and burgonet remained in use until the use of firearms superseded hand weapons.

Incised tablets from Mavesyn Ridware showing Norman and twelfth-century helmets.

Basinet with pointed visor and mail aventail. Note the removable pins on the hinge that enable the visor to be completely removed. (Author’s collection)

The Coif and Arming Cap

As this chapter is primarily concerned with the protection of the head, we should look at what lies beneath the helmet first. In fashion, throughout the medieval period, both male and female wore a simple, cotton skullcap or coif as a protection from the general weather and infestation, for example. In some cases, the coif was the only thing worn on the head but more often a hood, or later a fashionable hat, was used and as such, the coif was seen as a form of underwear. The advancement of this simple, cotton coif to become padded for protection was a simple process. Horsehair or wool was stitched into two layers of material and a series of stitched lines or crosses held the padding in place. With the advent of larger helmets, a padded ring known as an orle was worn around the head and, in some cases, the orle and coif was combined to make an arming cap. A very clear representation of a thirteenth-century arming cap can be seen on a sculpture on the front of Wells Cathedral. The padded coif would eventually give way to elaborate linings that would be designed purely for the helmet.

As a footnote, a leather or bone collar could be used to protect the neck and was worn over the arming cap but beneath the mail coif. An example of this collar can also be seen on a sculpture on Wells Cathedral.

Sculpture on Wells Cathedral showing padded arming cap and whalebone collar. The illustration shows how the padded Orle keeps the helm away from the head.

Mail Coif

The early padded coif protected the head and hair from the mail hood that was made of iron rings riveted together. This hood was also known as a coif and, without the helmet, still gave the head some protection from glancing blows and cuts.

The method of producing mail was already ancient by the eleventh century, and the ability to make complex shapes that fitted the head would not have been difficult to the skilled armourers of the time. The process of making mail is fairly simple, but very labour-intensive. Wire must be obtained by pulling hot iron through a series of holes that reduce in size. Eventually a long strip of wire is produced, which is then wound around a rod called the mandrel, thus making a spring. This is then cut along its centre, which makes individual rings. The heating and slow cooling of the rings softens the metal making it easy to bend, flatten and pierce. Each ring, or the joint ends, are flattened and overlapped where a hole is punched through; this hole receives a rivet, which closes the link tight. Linking each ring to create a chain begins the process of making mail, followed by adding links to each alternating ring. When the garment was complete, the mail was heated and quenched to harden the metal. Creating such large amounts of mail employed whole villages on an industrial scale.