Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

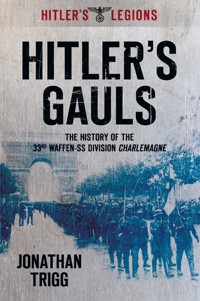

The divisions of the Waffen-SS were among the elite of Hitler's armies in the Second World War. But alongside the Germans in the Waffen-SS fought an astonishingly high number of volunteers from other countries. By the end of the Second World War these foreign volunteers comprised half of all Hitler's Waffen-SS, and filled the ranks of over twenty-four of the nominal thirty-eight Waffen-SS divisions. So during the most brutal war that mankind has ever known, hundreds of thousands of men flocked to fight for a country that was not theirs, and for a cause that was one of the most monstrous and barbaric in history. Who were these men, and why did they fight? Hitler's Gauls is an in-depth examination of one of these legions of foreign volunteers, the Charlemagne division, who were recruited entirely from conquered France. The men in Charlemagne, often motivated by an extreme anti-communist zeal, fought hard on the Eastern Front including battles of near annihilation in the snows of Pomerania and the final stand in the ruins of Berlin. This definitive history, illustrated with rare photographs, explores the background, training, key figures and full combat record of one of Hitler's lesser known foreign units of the Second World War.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 345

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Hitler’s Gauls

The History of the 33rd Waffen-Grenadier Division

der SS (französische Nr 1) Charlemagne

Book 1 in the Hitler’s Legions series

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his thanks to a number of people, without whose help and support this book would never have been written. First to the Charlemagne veterans, André Bayle and Gilbert Gilles, who took the time to humour an obsessive Englishman, and to Anthony ‘Gurkha’ Corbett and Katie Monach who spent many hours translating all the author’s correspondence to and from the said veterans to make up for his truly appalling French. To Frau Notzke at the Bundesarchiv who patiently helped find material when I wasn’t being very specific, to my editor, David, and Kim at Spellmount who put up with endless stupid questions, and to my publisher, Jamie, a straight batter if ever there was one, thank you. To Tim Shaw, a reproduction wizard and a true friend, again thank you. Lastly to my wife, as beautiful as she is patient, she has managed to feign interest in this project for almost two years, and for that I thank her.

Contents

Title

Acknowledgements

List of Maps

Introduction

I France: The Rise of the Extreme Right

II Germany: The Birth of the Waffen-SS

III 1940: Blitzkrieg and French Collapse

IV The Waffen-SS and Foreign Recruitment

V Frenchmen on the Eastern Front: The LVF

VI Formation of the SS-Sturmbrigade Frankreich

VII French SS First Blood: Galicia

VIII A New Beginning: The Formation of Charlemagne

IX Hell in the Snow: Pomerania

X

Götterdämmerung

in Berlin: The End of Days

XI Aftermath: The Reckoning

XII Military Impact. Was it worth it?

Appendix: Waffen-SS Ranks

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

List of Maps

1: Battles of the LVF and the SS-Sturmbrigade 1941–1944

2: Charlemagne – The Pomeranian Campaign, February–March 1945

3: The Battle of Berlin, April–May 1945

Introduction

The nightmare was finally at an end. The evil of Adolf Hitler and Nazism was burning in the vast funeral pyre that was the capital of the much-vaunted ‘Thousand Year Reich’. Smiling and joyful Red Army soldiers watched as Sergeants M A Yegorov and M V Kantaria from the Soviet 150th Rifle Division triumphantly hoisted the hammer and sickle Red Banner No.5 on the rear parapet of the ruined Reichstag on the afternoon of 2 May 1945. That image of victory was caught on camera for publication all over the world. This symbolic act established beyond doubt the total victory of Soviet Russia over Nazi Germany. Although as was so often the case in Stalin’s Machiavellian world, the truth was not as represented to the world; it later transpired that the first soldier to raise a Soviet flag over the Reichstag building was in fact an artillery captain more than twelve hours earlier than officially recognised. It was decided at the time however that the photo taken of that event lacked the proper background to establish the site in the audience’s mind, so the official Soviet war photographer selected the rear parapet as the site and Sergeants Yegorov and Kantaria as suitably ‘proletarian Soviet’ heroes for the now-famous picture.

For Soviet Russia the fact that the Reichstag itself had been closed since the infamous fire of 1933 was irrelevant. Final German armed resistance might well have been concentrated around the Chancellery building and the Führer Bunker in its garden, but for the Soviet people at home waiting desperately for news of final victory, the Reichstag was the ultimate symbol of Nazi Germany, and to see it humbled was to finally know the war in Europe was over.

Below the antics of staged propaganda cinematography there were long, though as a vivid reflection of the bitterness of the fighting, not over-long columns of defeated German soldiers, sailors and airmen winding their way slowly and dejectedly through the rubble-strewn streets and into the uncertain tender mercies of Soviet captivity. Many of the faces of those defeated soldiers were of old men, the last remnants of Germany’s citizen home guard, the Volkssturm, thrown into battle by the crumbling Nazi Party hierarchy in a last desperate attempt to stave off final defeat. Most heartbreaking of all though, particularly for the surviving civilians of Berlin watching the pathetic end of the drama, were the columns of boys from the Hitler Youth being marched away to the horrors of the gulags. These boys, some as young as 12 or 13, dressed in scraps of ill-fitting and oversized uniforms, had been called to action alongside their grandfathers in the Volkssturm and were now paying the price of their futile resistance. For so many the rubble of Berlin would be their last sight of Germany. Few would ever return to their homeland alive.

But not all in the defeated Nazi ranks were grey-haired grandfathers or beardless boys. Some were hard-faced young men with the still proud bearing of Germany’s feared and respected ‘Frontschwein’, combat veterans, and it was one of these that a drunken Red Army soldier singled out from his comrades and pulled out of line. The Soviet soldier screamed accusingly at his defeated enemy the same phrase that Russian soldiers, and indeed civilians, had come to fear and loathe since the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, ‘SS, SS’. But before the Russian could do anything about his accusation the singled out soldier was pulled away from his grasp and hustled back into line by yet another Russian guard. The relieved POW turned to his fellow captives and said with a sigh of relief, ‘That was a narrow escape!’, only for the drunken Russian to grab him again, pull him to one side away from his comrades, shove a pistol against his forehead and pull the trigger. He was dead before he hit the ground. In the orgy of conquest common to most victorious armies in history, this incident was sadly commonplace and, unfortunately in respect of human life, hardly worthy of historical note, except for certain facts.

The first was that the Russian soldier singled out that captive deliberately; this was no random act of savagery. The murdered man was not executed for who he was but rather for whathe was, a member of an organisation that had carved its name in blood across the Russian steppes, the SS. In this regard the Russian was correct in his identification at least; the murdered soldier was indeed SS, in fact a Waffen-SS Unterscharführer, a full corporal. Secondly, and of critical interest, is the fact that the Unterscharführer didn’t speak to his comrades moments before his death in German, but in French. In fact the murdered man wasn’t German at all, but a Frenchman; his name was Roger Albert-Brunet, a native of Dauphine and a winner of the Iron Cross 1st Class, and he wasn’t the only Frenchman there from the Waffen-SS in the burning ruins of Berlin.

With the European phase of World War II finally over, Berlin had become a battlefield in common with dozens of cities across Western and Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. And like Leningrad, Minsk, Warsaw and Rotterdam, it too had paid the price in fire and ruin. Like so many urban landscapes of the previous six years, the German capital was dotted with the debris of modern warfare. Around the shattered buildings and scattered throughout the wrecked city lay the burning hulks of Russian tanks and self-propelled guns, destroyed mainly by small bands of tank busters operating on foot and armed with nothing more sophisticated than hand-held anti-tank weapons, the ubiquitous Panzerfäusts, a simple metal tube with a hollow charge attached and a range of less than 100 metres. Heaps of dead Soviet infantrymen lay thickly strewn up and down the once beautiful Berlin streets, testament that though the battle was short it was also savage and cost the Red Army dear. Indeed Soviet casualties in the taking of Berlin totalled 78,291 men killed and 274,184 wounded, and this against an enemy in its death throes.

So was this desperate defence the last throw of the much-vaunted German Aryan superman? The racial German Herrenvolk? Actually no, many of these diehard defenders fighting on to the bitter end were non-Germans: Balts, Norwegians, Danes, Swedes and Frenchmen. These latter were the remnants of the 33rd Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS (französische Nr.1) Charlemagne. French Waffen-SS men?

In a century dominated by strident nationalism how and why were soldiers of half-a-dozen different nationalities fighting to the last man for a regime that had invaded most of their homelands and was undoubtedly one of the most bloodstained and horrific in history? For the French grenadiers in particular, how could countrymen of the victims of atrocities such as Tulle and Oradour-sur-Glane wear the hated lightning flashes, the pagan sig runes of the Waffen-SS, until the very end? From where did they come? Why did they do what they did? What is their story?

CHAPTER I

France: The Rise of the Extreme Right

The road to a murdered French Waffen-SS volunteer in a burning Berlin began decades earlier in the mud and slaughter of the Western Front in World War I. The years of carnage in the trenches dominated post-World War I France, and led to twenty-one years of political and social turmoil that created the breeding ground from which Charlemagne,and the men who served in it, would spring.

The end of the war to end all wars saw France emerge victorious, but exhausted. With her Allies she had defeated Prussian militarism, and regained the provinces of Alsace-Lorraine lost after her defeat in the Franco-Prussian War forty-seven years earlier. However, the price had been extraordinarily high. France had lost over one-and-a-half million men killed and more than four million wounded; the war had mainly been fought on her soil and much of northern France was laid waste. In human terms France’s national consciousness was to be forever haunted by the multitude of monuments to her fallen that sprang up in every city, town and village in the land.

Post-war chaos

The post-war political chaos that infested so many nations, Germany and the new Communist Russia being prominent among them, also resonated in France. Between 1918 and 1940 France had forty-two separate governments, lasting on average just six months. In the three years from 1932 to 1935 alone, there were eleven different administrations presiding over fourteen ‘national economic recovery plans’. Chronic political insecurity and instability led many in France, just as in neighbouring Germany, to look to the political extremes of the far Left and Right for the answers. In France communism found a ready home in a nation with a long tradition of working-class radicalism and revolution. After all France was the setting for the storming of the Bastille and the Paris Commune. Balancing the growth of the far Left was the explosion of support for the splintered politics of the far Right. Here aristocratic monarchists rubbed shoulders with working-class nationalists, representatives of big business and a bourgeoisie desperate for stability and order. This conglomeration of the unlikely found particular expression in the founding of mass membership political organisations, often with paramilitary overtones.

The largest and most influential organisation was L’Action Française, an umbrella grouping for right-wingers of all shades and hues, with a strong pro-monarchist streak. This organisation was founded by the leading French thinker, Charles Maurras, but it was by no means the only group on the far Right. There was a proliferation of rightist organisations, such as the ex-French Army Colonel de la Roque’s Croix de Feu, mainly made up Great War veterans, or for those more dedicated to the extremes of armed action there were the shadowy paramilitaries of Eugène Deloncle’s Comité Secret d’Action Révolutionnaire, better known as Les Cagoulards, the Hooded Ones. Young people were accommodated in the champagne magnate Pierre Taittinger’s Jeunesses Patriotes founded in 1924, a movement with echoes of the yet-to-be-born Hitler Youth, and while there is no doubt that there was a great deal of overlap in membership, it is also clear that the far Right in France at the time was a mass movement with genuine popular support.

Though nowhere near as violent as the corresponding situation in Germany, where right-wing veterans of the Great War joined the freebooting Freikorps bands and fought a virtual civil war with their enemies of the Left, street violence became commonplace in France’s cities and added to the general feeling of chaos and dissatisfaction that successive governments were unable to deal with. Confidence in the Republic’s establishment and the body politic was low and nothing seemed to be able to reverse the decline. When large numbers of mainstream politicians were implicated in the infamous Stavisky Affair in February 1934, so-named for the Ukrainian Jewish fraudster at the centre of the financial scandal, L’Action Française incited street riots and its supporters invaded the National Assembly building in Paris. The bloody street fighting between the police and right-wingers on the night of 6 February 1934 left six people dead and over 655 others in hospital. The reverberations of the violence were felt all over France, and in the shocked aftermath the Republic acted to protect itself by banning a host of politically motivated organisations that were not officially designated as political parties. This heavy handed approach was a conspicuous failure. The Croix de Feu for instance was banned only to resurface as the official Parti Social Français (PSF) with an official membership of 800,000 by 1936. The formation of the leftist Popular Front Government in 1936 under the Prime Minister, Léon Blum, only served to inflame the bigotries of the extreme Right and unite its disparate factions in opposition, particularly as Blum was Jewish. He himself was to remain a focus for right-wing hatred until the outbreak of World War II and the extreme Right could exact its revenge.

Extremist ideology and politics

The growth of the far Right in France was not purely in the arena of popular political activism. It was also given succour by certain strands of French intellectualism. France has a long tradition, unlike Great Britain for instance, of attaching huge importance to the thinking of its own home-grown intellectuals, and of that same thinking having a far-reaching influence on the mainstream population. Several of the French intellectual elite of the day were at the forefront of the Europe-wide fin de siècle intellectual movement whose ideas of a unique European cultural heritage and the growing threat from the East found a ready home on the political extreme Right in France. Recurrent themes written and debated about were the supposed weaknesses and decadence of the European liberal democratic model of government, and the twin perceived threats of international communism and Jewish-controlled capitalism. The intellectuals’ solution was a pan-European alliance that would combat the alleged tide of barbarism from the East that threatened to engulf Europe’s unique cultural inheritance. These same thinkers believed that Europe needed a revival, a rebirth, and, crucially, that this was not going to be a French-centred act but rather a ‘European’ one. When World War II came it was seen by them and their supporters as a fight to preserve European culture, values and heritage, as well as European hegemony. One French writer who later became an active collaborator, Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, wrote as early as 1922 in his Mesure de la France:

…we must create a United States of Europe, because it is the only way of defending Europe against itself and against other human groups.

Such writings gave extreme Right political parties an intellectual legitimacy they had previously been lacking and helped them to flourish. While the banning of organisations such as the Croix de Feu only served to channel their members into active participation in legitimate political parties.

Jacques Doriot

The Parti Social Français might have had a membership of close to a million, but it was not the largest or most influential pre-war party of the extreme Right in France. That position went to the Parti Populaire Français (the PPF), led by the well-known and charismatic politician, Jacques Doriot. Doriot was a typical far Right leader of his day with a political pedigree that began in the theatre of working-class struggle on the Left before moving inexorably to the Right. In this he unthinkingly aped the far better known Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini, himself a figure who began on the Italian extreme political Left to finally end up as Italy’s fascist supremo. Doriot was born on 26 September 1898 at Bresles, in the department of Oise. He moved to Paris in 1915 and became a labourer in the industrial Parisian suburb of Saint-Denis. He joined the Jeunesses Socialistes de France (the Socialist Youth of France) in 1916 aged 17, and was then mobilised the following year to serve in the trenches where he won the Croix de Guerre in combat. He was subsequently captured by the Germans and held prisoner until the armistice.

On his repatriation to France, Doriot joined the newly-formed French Communist Party in 1920 and thereafter rose rapidly through its ranks, becoming a member of the presidium of the executive committee of the Communist Internationale in 1922, Secretary of the French Federation of Young Communists in 1923, then serving a short sentence in La Santé prison in Paris for opposition to Poincaré’s occupation of the Ruhr, before being elected to the Chamber of Deputies to represent the Seine region in 1924. After a period in the Chamber he confirmed his ascendancy by being elected to the politically powerful position of Mayor of Saint-Denis in 1931. In French political life a mayoralty is highly sought after (the current French President Jacques Chirac based his drive for presidential power on his mayoralty of Paris), and this post enabled Doriot to establish a political power base independent of the Communist Party, giving him control over his own private fiefdom in the heart of the French capital.

Prior to his election Doriot had withdrawn from the leadership of the French Communist Party over his doubts as to the rigidly held dogma of a Communist Party-only ticket to achieve political power. But it was while Mayor of Saint-Denis that he began to openly discuss the possibility of alliances with other leftist parties as part of a coalition for power. This was heresy to the Communist Party apparatchiks, and he was expelled from the Party in June 1934. Their reasoning was clear: Doriot’s pragmatic approach clashed with the Party line that decreed that the Communists were the only standard bearers of the workers and all other parties were actually pseudo-bourgeois. The expulsion was a bitter blow for Doriot personally. He saw it as a rejection by the Party he had served all his political life, but he refused to leave politics and decided instead to remain in the Chamber of Deputies and form his own party which would be based on his ideas and political leadership.

Thus was born the PPF on 22 June 1936. Expansion was rapid and PPF membership soon topped 250,000. As the party grew Doriot increasingly shifted ideologically to the Right and unsurprisingly became a virulent anti-Communist; in this it is hard not to see a great deal of personal bitterness against his former comrades. Doriot began espousing fascism, expressing admiration for Mussolini in particular, and he also used the Party paper, Le Cri du Peuple (The Cry of the People), to advocate collaboration with Europe’s other rising political and economic star, Nazi Germany, whose seeming resurgence under Hitler greatly impressed him. In the apparent rebirth of Italy and Germany Doriot saw France’s future; a future where she would reaffirm her place as one of the pre-eminent nations in the world in her new form as a fascist state.

The PSF and the PPF were the largest of the pre-war French political parties of the far Right but they were far from alone. Indeed the far Right of the political spectrum in France was remarkably crowded with a host of minor parties that came and went, but not until the former cabinet minister Marcel Déat’s Rassemblement National Populaire (RNP) was established on 1 February 1941, was there anything of the same magnitude as the PSF or the PPF. While often bitterly bickering amongst themselves, what these parties actually did was establish a popular acceptance and legitimacy in France of the far Right and its thinking. For many party members, particularly the youngest, often the most idealistic and committed, this meant a glamorisation of Hitler’s Germany in particular, and the ideal of a pan-European future as opposed to a purely French one. These seeds were sown on fertile ground in France and such supra-national thinking was to lead directly to the creation of Charlemagne.

Joseph Darnard

Doriot was the leading party political figure who impacted greatly on French opinion, and who helped sow the seeds that would later lead to Frenchmen fighting it out with the Red Army in Berlin’s burning ruins. But outside this purely political influence, the best known, and now most infamous figure, was undoubtedly Joseph Darnard.

Born on 19 March 1897 in Coligny of humble stock, his father was a railway worker, the patriotic young Joseph joined the 35e régiment d’infanterie of the French Army on the outbreak of World War I and went on to serve with distinction, winning no fewer than seven separate citations for bravery and specialising in leading daring groups of raiders into German-held territory. After the War he applied for a regular commission to continue his move up the ladder of military promotion; however he was refused, and somewhat disillusioned at what he saw as a snub, decided to leave the Army altogether and pursue an alternative career. He became a cabinet maker initially and then set up his own highly successful transport company operating out of Nice. Whilst building his business Darnard became active in politics, supporting the royalist L’Action Française like many of his fellow Great War veterans.

During his time as a supporter of L’Action Française Darnard began to associate with the more extreme fringes of the organisation and eventually he graduated into hard core militant activity, particularly with the secretive Cagoulards. In support of this shadowy paramilitary group Darnard used his business activities as a cover to smuggle weapons into the country from abroad and eventually became their chiefin Nice. The smuggled arms were stockpiled in a series of secret locations to be used by Les Cagoulards against what they perceived to be any threats to the nation, the greatest of which was their fear of an internal communist-led insurgency and an ensuing civil war. Given his escalating involvement with the militants it was only a matter of time before Darnard’s activities came to the attention of the police and security services. That moment finally came when he was implicated in the murder of a low-level criminal, Maurice Juif, who was said to have double-crossed Les Cagoulards. Darnard was arrested, questioned and detained for six months by the police, but subsequently released with an off-the-record warning to halt further activity unless he wanted to end up in prison again. In the aftermath of this lucky escape Darnard wound down his involvement with Les Cagoulards and bided his time.

CHAPTER II

Germany: The Birth of the Waffen-SS

In Germany the political earthquake had already happened, and now standing guard at the Chancellery were black-clad giants of the Waffen-SS, staring impassively forward. The Waffen-SS? Who were they? Where did they come from? What was the tradition from which they sprang? The key to understanding this hitherto unknown organisation and its subsequent growth lay in Germany’s past.

Germany is born

Prussia’s Iron Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, created Imperial Germany from a multiplicity of Germanic mini-states, and that nationhood was made possible by war with the key battles being fought in the Austro-Prussian and Franco-Prussian Wars at the end of the 19th century.

This Germany, a country born in the unification wars and possessing huge economic and military muscle, had challenged the established imperial countries of France, Great Britain and Russia in a bid to join their ranks as a Great Power in the world. This challenge led to World War I, the mud and death of the Marne, Tannenberg, Verdun, the Somme and Ypres, and finally to Germany’s capitulation and the ignominy of the Versailles Treaty. Germany’s humiliation was felt most keenly on the issue of land. Denmark and Belgium benefited from their annexation of Schleswig-Holstein and the Eupen-Malmédy regions respectively, and the resurrected state of Poland was given access to the Baltic Sea via a land corridor through Germany with the Free City of Danzig at its head. For France the disputed provinces of Alsace-Lorraine (annexed by a victorious Prussia at the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871) were returned. To add to this burden Germany was humbled economically with the imposition of huge sums to be paid in war reparations. The Spanish flu pandemic then ravaged a war-weary German population weakened physically by years of food shortages brought on by the successful British naval blockade. This was followed by the global Great Depression with hyperinflation and the near collapse of the entire financial system in Germany. The result was a German state in near total meltdown. In less than twenty years Germany had lost the largest war ever fought in world history, several millions of its people through war, hunger and disease, and been brought to the verge of complete economic collapse. Politically these conditions were the basis for Hitler’s rise.

On the military front the once-proud Imperial German Army and military machine was emasculated by the terms of the Versailles Treaty. The newly-established German Army, the Reichswehr, was capped at no more than 100,000 men, a number considered adequate for defence. The Reichswehr was also denied emergent military technologies with a ban on possession of any armoured vehicles including tanks. Germany was prohibited from having an air force for the Reichswehr to operate with, and her navy, the Kriegsmarine, was limited to having ships of less than 10,000 tonnes displacement. However from the date of the Treaty’s signing the German High Command had seen its mission to be finding ways around the restrictions. Results included a strategy for the Kriegsmarine based on U-boats and ‘pocket battleships’, a new Luftwaffe secretly trained in Soviet Russia and an Army structured as a basis for rapid expansion. Hitler’s reassurances to the generals that the restrictions imposed by Versailles would be progressively dismantled ensured their support in his bid for power, and indeed on Hitler’s election to the Chancellorship on 30 January 1933 he immediately began a process of rapid rearmament that flouted Versailles to the benefit of the armed forces. This policy though did not solve all the issues between the Army and the Nazis. Indeed this relationship between the two dominant institutions in German life would remain a source of huge tension until after the 20 July 1944 bomb plot against Hitler. The aftermath of that unsuccessful assassination attempt would finally see the last vestiges of army independence broken in the show trials of high ranking officers conducted by the Nazi state prosecutor, Roland Freisler.

The coming of the Nazis and the Brown Shirts

In the chaos of the Weimar Republic years the politics of the day became heavily radicalised. There was no centrist consensus and the parties of the extreme Right and Left flourished. Political violence was commonplace and widespread. Communist Party supporters regularly fought it out in the streets with supporters of the biggest extreme right-wing party, Adolf Hitler’s National Sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiter Partei (NSDAP), the Nazis. At the time politics revolved around the hustings, with politicians touring the country drumming up support at rallies both big and small. Supporters of rival parties often attended to disrupt the speeches and physically attack the speakers. Informally at first groups of men were formed to protect speakers. For the Nazis this saw the foundation of the ubiquitous Brown Shirts of the SA, the Sturmabteilung, storm troopers.

The SA was led by one of Hitler’s oldest and closest friends and political allies, Ernst Röhm. This burly ex-soldier saw the Nazi mission as one of creating a new social order in Germany, one where the power of the army and the industrialists was replaced by a true mass social revolution that would be led by the Nazi Party with his brown-shirted storm troopers in the vanguard. From humble beginnings the SA grew from a handful of men to almost three million members by the end of 1933. Invaluable when the Party was vying for power, on his accession to the Chancellorship the SA became an embarrassment to Hitler and a bone of contention in his relationship with the generals. In 1933 the army was still the one institution capable of standing up to the Nazis and so needed to be placated. This was becoming increasingly difficult due to Röhm’s loud and public advocacy of the eventual replacement of the army by the SA, and his growing impatience to begin his promised ‘revolution’.

Men in black: the SS

In order to remove the problem once and for all Hitler turned to the Nazis’ other private army, the SS. Established originally as the Stabswache, or Staff Guard, to protect Hitler personally, the unit initially consisted of just two men, Josef Berchtold and Julius Schreck. It evolved into the Stosstrupp Adolf Hitler, and then finally the Protection Squad, in German the Shützstaffel, or SS. During its various transitions it came under the leadership of a man who seemingly excelled only in his ordinariness. Bespectacled, of medium height and physically unprepossessing, with a reputation as a competent Nazi Party administrator in his native Bavaria, Heinrich Himmler was in reality anything but ordinary. Much has been written about Himmler and why such a seemingly inconsequential man could become the monster he undoubtedly was. A particularly good description of the enigma that was Himmler was written by the sometime diplomat and journalist Edward Crankshaw:

He was not distinguished by cruelty, by lust, by excessive vanity, by overweening ambition, by systematic deceitfulness. His qualities were unremarkable, vices and virtues alike. But there was no centre: the qualities simply did not cohere.

There are men like Himmler in the prisons and criminal lunatic asylums all over the world – and, more unfortunately placed by virtue of the possession of private incomes, leading retired and slightly dotty lives in seaside bungalows along our coasts. They are the sort of men, good husbands and fathers, kind to animals, gentle, hesitant, soft-spoken, absorbed in some mild hobby and probably very good at it, who murder their wives because they wish to marry another girl and flinch from the scandal of a divorce.1

Himmler epitomised the unremarkable face of evil, but Hitler saw in him the one quality he prized above all others, loyalty, and in time Himmler was to become referred to by Hitler as ‘der treue Heinrich’. He would keep this soubriquet until the last month of the war when his master found out about his futile peace feelers through the Red Cross’s Swedish envoy, Count Folke Bernadotte.

Himmler was fascinated by the occult, herbalism, Germanic paganism and genetic racial theory and he would prove to have an exceptional talent for both organisation and conspiracy. In the SS Himmler saw the means of his own rise to power. Eventually the organisation he created and controlled would become, in effect, a state within a state in Germany, and the key to that was the formation of armed units.

The creation of such an armed force, independent of the army, was not uncommon in continental Europe, where many countries were long used to armed police forces and even paramilitary units designed to combat civil unrest. In this context the formation by the German government, as the Nazi Party had become, of a small paramilitary formation did not seem out of place. The fact that this formation was entirely at the personal disposal of the Führer and utterly obedient to him, and not the institutions of the state, was nothing more than an administrative issue as far as most Germans were concerned.

This idea of a ‘political army’, however, has always been difficult to understand in countries where the army is the only legitimate institution of the state allowed to bear arms, and is strictly separate from politics. In the UK for instance witness even now the discomfort and alarm felt by most of the population at the prospect of selectively arming police officers on a regular basis. The notion of a party political leader, such as Churchill or Attlee, forming armed groups would have been total anathema and utterly incomprehensible.

Night of the Long Knives

It was precisely these ‘administrative circumstances’ though that allowed Hitler to lance the boil of Röhm and the SA. On 30 June 1934 SS formations left their barracks to break the power of the SA once and for all in the ‘Night of the Long Knives’. The premier SS formation, the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler under its commander Josep ‘Sepp’ Dietrich, left its barracks in Berlin Lichterfelde and headed for the Bavarian spa resort town of Bad Wiessee where Röhm had gathered many of his SA leaders for a relaxing conference. Their orders were clear. Round up the SA leaders and then shoot them immediately. Röhm himself was arrested and offered the opportunity to commit suicide; in total disbelief at the situation he refused and was shot dead by his erstwhile comrade Theodor Eicke (later commander of the 3rd SS Panzer Division Totenkopf). Most of the senior SA leadership nationwide was murdered, many of them shouting ‘Heil Hitler’ as they faced the firing squads, believing they were victims of an SS plot to overthrow the Führer – misplaced loyalty indeed. Following this act of Nazi fratricide the SS was allowed to expand by a grateful Hitler.

The organisation became an independent arm of the Nazi Party, no longer subject to the control of the SA as it had been up until then. In a decree of September 1934, Hitler outlined the main task of the new force. Trained on military lines, it was to be ready for a fanatical war of ideology that would break out within Germany should the regime’s opponents rebel. Only in the event of general war would it be employed for military purposes, in which case only Hitler could decide how and when it would be used. The Reichswehr was not entirely comfortable with the arrangement but Field Marshal Blomberg, the Defence Minister, was reassured by Hitler that the intention was to create an armed police force and not another army. This reassurance, like so many of Hitler’s, proved entirely false.

Himmler’s fantasy: the new Teutonic knights

Himmler, now officially entitled Reichsführer-SS, patiently went about fulfilling the fantasy he had constructed in his own mind for the future of the Waffen-SS. Himmler’s fervent imaginings foresaw a German Empire dominant in Europe with huge colonies in the Lebensraum, living space, of the East. These colonies would be manned by a new breed of ‘warrior-farmers’, tall, robust, blond haired and blue-eyed Aryans, dedicated to the establishment of the Nazi ideal and the destruction of Bolshevism and Jewry. This new order of Teutonic centurions would have the Waffen-SS as its vanguard. Sired by ‘pure’ Aryan bloodlines and forged in the cauldron of battle the Waffen-SS would symbolise the zenith of Nazism and be a potent display of its victory over the so-called inferior races. Incredible as it seems now, it would be this lurid vision that would see non-Aryan Frenchmen fighting in Berlin under the banner of the Waffen-SS a scant decade later.

The Waffen-SS began to emerge rapidly as an organisation following the purge of the SA, and was formed at its core around three distinct units. First was Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit, the elite Leibstandarte. An independent force even within the SS, the Leibstandarte was known firstly for its incredibly strict entrance criteria; Himmler’s boast was that a single filled tooth disqualified a candidate, and secondly its ill-deserved reputation as ‘asphalt soldiers’ due to its use for ceremonial duties. Second was the SSVT, the Verfügungstruppen or Special Purpose Troops, and lastly the infamous Totenkopfverbände, the Death’s Head Units. These latter were formed to guard Nazi Germany’s burgeoning concentration camp network and were noted for their brutality and fanaticism. The Waffen-SS was promoted by Himmler as a new German imperial guard to attract ex-regular army soldiers, and the SSVT in particular saw an influx of extremely capable officers who would transform the essentially paramilitary outfits the SS were, into the first-class fighting formations envisioned by Himmler. This was the situation that was half-feared, yet half-hoped for, by their ultimate creator and father, Adolf Hitler. This influx of ex-regular army men who joined the black band were given the power to institute a series of reforms that established a military infrastructure that still has echoes in the professional armies of today.

Names to remember

But the story of Charlemagne is more than the story of political extremism and anti-communism in France, or the creation and growth of the SS; it is at heart a story of thousands of individual Frenchmen who made a conscious decision to become members of Hitler’s black guards. Charlemagne’s history does not begin in the early years of the war when the Waffen-SS was still an unknown and minor part of the huge and mighty Greater German Wehrmacht. In 1940 for example, there were over 10,000,000 German men aged between 18 and 34, of whom more than 6,600,000 were in the Wehrmacht, and only a tiny 50,000 were in the Waffen-SS. At that stage of the war, atrocities such as those at Le Paradis and Wormhoudt carried out by the Leibstandarte and the Totenkopf were still rare occurrences and could be viewed as aberrations, but by late 1944 when Charlemagne was being established the curtain was fast descending on the Nazi Empire and the name of the Waffen-SS would now be forever linked to the barbarities of the Eastern Front. Yet men still flocked to join; one French volunteer said of his decision to enlist:

In 1940 the German soldiers filled me with admiration and horror. In 1943 they began to inspire pity in me. I knew that they were facing the entire world and I had a feeling that they were going to be defeated.

After Stalingrad and El Alamein, we hardly ever saw any more tall, blond athletes. In the streets of Paris, I passed pale 17 or 18 year old adolescents with helmets too large for them and Mausers of the other war. Sometimes also old men with sad eyes …

But suddenly reappeared small groups of soldiers true to the legend. Tall, silent, solitary, with both hardened and childish features. They returned from hell and the Devil was their only friend. On their collar the two ‘flashes of lightning’ of the Waffen-SS.2

So who were these volunteers and what was their story before Charlemagne?

Henri Joseph Fenet did not look the classic image of the Waffen-SS man. Of medium height he had a serious, bookish air, accentuated by the round rimmed spectacles he always wore. He was an intense young man not given to overt displays of emotion. Born on 11 July 1919, in Ceyzeriat in the Department of Ain, into a middle-class family, Fenet had no major political involvement prior to the outbreak of World War II, and was in fact a 20-year-old student preparing to become a teacher. His pre-war life was entirely unremarkable; that would change with the coming of war as he rushed to join up and defend his country.

Pierre Rostaing, on the other hand, was anything but unremarkable in the first place. Rostaing was not a patriotic citizen soldier like Fenet, volunteering when war came calling, but a professional career soldier. France has always produced such men, more comfortable in the rigours of combat than in civilian life, and this empathy with the battlefield was Rostaing’s defining characteristic. He looked every inch the combat soldier, in that he was tall, strong and with a definite air of self-confidence. He was born on 8 January 1909, in Gavet in the Department of L’Isere into a working class family, and he enlisted in the French Imperial Army aged 18. Like so many of his comrades at the time he served abroad in France’s vast overseas Empire, completing postings in Indochina, Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia in the twelve years he served in the army prior to 1939.

On the outbreak of the so-called Winter War in 1939, when Soviet Russia invaded tiny Finland, Rostaing was genuinely appalled by the communist invasion and saw in it the first act in an eventual Bolshevik assault on all Europe. The 2ebureau de l’Armée, French military intelligence, accepted him as a volunteer to go to Finland as a ‘technical advisor’. This then was a forerunner of things to come as the Frenchman found himself fighting with the superbly trained and motivated Finnish forces against a Soviet enemy that vastly outnumbered them in both men and material on a battlefield of snow and ice. For Rostaing his battle with the Red Army would go on for almost the next seven years.