16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Now an established classic on the subject, this new 2021 paperback edition of Hooked on Bass shows anglers how to catch bass, particularly the bigger fish, from the shore. With excellent photography and clear, detailed diagrams to help illustrate the advice, any angler, beginner or expert, who has caught or would like to catch bass will find endless value in the pages of this book.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

HOOKED ON BASS

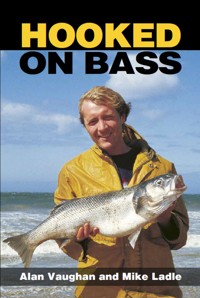

Mike and Alan relax with an 8½lb fish which took Mike’s peeler crab in shallow water over rough ground.

HOOKED ON BASS

Alan Vaughan and Mike Ladle

First published in 1988 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

New edition 2003

Paperback edition 2021

This e-book first published in 2021

© Mike Ladle and Alan Vaughan 1988 and 2003

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 938 9

Acknowledgements We wish to thank Dave Cooling, Dave Williams, Martin Williams and Phil Williams for reading the original manuscript; Terry Gledhill for supplying a number of photographs; and Ian Farr for preparing black and white prints. Lesley Vaughan deciphered out scrawl and typed the final draft. We are also grateful to those anglers who supplied us with valuable information.

Contents

Preface

Introduction

1 The Life Cycle of the Bass

2 Food

3 Natural Baits

4 Tackling Up for Bass

5 Shallow Rocky Shores

Plates

6 Fishing Deeper Water and Other Methods

7 Sandy Beaches

8 Estuaries

9 Pier Fishing

10 Where and When to Fish

11 Some Successful Venues

12 Dreams Do Come True

13 Still Hooked on Bass!

Index

Preface

The plug landed twenty yards out in the seething waves and, as it hit the water, it was seized violently. The clutch whined and line was torn from the spool as the bass ran out to sea. The 8½lb fish fought with great speed and power, making full use of the strong current and the surging undertow. Dave appeared at my side as I slid my catch on to the flat, wet rocks, an event which we repeated no less than forty-seven times in the next two hours.

I rushed along the beach to see the magnificent bass that Phil had just beached. He weighed it and the balance went down to 10½lb. With trembling fingers I baited up with a large soft edible crab and cast out. I felt a slight twitch on the line and gave some slack; the line was taken up and a pull began to develop. I struck and the rod bent right over as line was taken against the clutch. This fish pulled harder than any bass I had yet caught and, when it eventually lay beaten at the edge of the ledge, it looked enormous. Phil lifted it ashore and we weighed it swiftly: 12¼lb. Two double-figure bass in fifteen minutes – fantastic!

This book is about catching bass from the shore. When we first spoke to each other – by telephone – it was to discuss something that Mike had written on the subject of bass angling. Without having met we agreed, almost without discussion, to write this book. It is based on the many letters which we wrote to each other, edited and expanded where necessary.

Introduction

When reading angling books it is often difficult to form any impression of the author’s character and experience. We thought that a thumbnail sketch of each of us, in terms of our bassing careers, might help to fill this gap.

ALAN VAUGHAN

I caught my first bass when I was seven years old from the pier at Ryde on the Isle of Wight. My father had already taken me fishing several times in a dinghy from the local angling club, and on this occasion I was using a rod he had made for me, expressly for fishing from the pier. In retrospect I realise that at the time my father was rather progressive in his attitude to fishing in the sea. Perhaps this was because of his experiences catching roach and trout in fresh water. The greenheart rods he made were not the heavy, stiff monstrosities now seen in the junk shops of most seaside towns, but they were slim and flexible and more like a modern-day spinning rod.

The small centre-pin reel had a braided line and the weight was a little spiral lead fixed some two feet from the hook, which was baited with ragworm. The worm was dangled underneath the pier at a point where the fish were known to lie and, whilst holding the rod, I had felt a pull and then caught a small bass of half a pound or so. We were fishing at night and, in the light of the lamps along the pier, my fish seemed such a glittering prize. A relatively late return home (for a seven-year-old) gave me the opportunity to show my fish to my mother and grandparents for their approval. I think that from that time on I have regarded bass as one of the most beautiful fish in the sea, and the fish I have most wanted to catch.

Since then I have fished for and caught many different fish, but always bass have been my number one obsession. I caught a lot of small bass when I was a boy and, as I read widely about angling during my teens, I became keener and keener to catch a bass of over ten pounds in weight; I have now realised that ambition several times. A good-sized bass is not only one of the most attractive and hardest-fighting fish, but has the added merit of being an excellent table fish. Large bass are not often easy to catch, so there is always a justifiable feeling of elation when a sizeable fish is brought ashore. These days, in the light of declining stocks, I also experience a great deal of satisfaction in returning bass to the sea to swim free again.

Since my days of worm dangling on the Isle of Wight, I have learned a lot about methods of catching bass. My efforts have mainly been directed towards the bigger fish so I have had only fleeting acquaintance with methods more suitable for the smaller specimens. Rarely these days do I fish the type of place where most fish are likely to be on the small side. On the whole most of my bass-fishing seasons have been spent fishing rough-ground areas by legering, usually with large crab or fish baits. I have landed many good fish, including ten to date which weighed over 10lb, the biggest at 12lb 14oz. These fish came from different places on the Welsh coast, from the Isle of Wight and from Devon, Cornwall and Eire. All of them were caught from the shore, and the methods used to catch them were comparatively simple. However, to catch good bass regularly a certain amount of single-mindedness is required, as well as a willingness to learn by one’s experiences; and, of course, at least initially, a decent helping of luck is useful.

The good news about catching big bass is that anyone who can cast twenty yards (not a hundred and twenty), who is willing to approach the business with an open mind and who has a moderate degree of patience, can succeed. If the hours that a typical sea angler clocks up during the year are assessed in terms of fish caught, then he might do better to go prepared for a few blanks and expecting to lose a bit of tackle, in order to feel confident that when the big fish comes along he is doing the right thing to catch it. This has been my philosophy for a number of years now and I always feel that, at any moment, a huge fish may take my bait. This is no different perhaps from the anticipation experienced by other anglers, but I know now from past experienceb that I am doing the right things and that big bass are not always so scarce. If the right time, place and tactics are chosen it is possible to take several big fish in a session. During one, exceptional, fortnight I caught eighteen bass with an average weight of over 8lb, including three fish in double figures.

An eight-pounder in peak condition.

MIKE LADLE

Unlike Alan I am not a born-and-bred bass angler. The first bass I ever caught was during my late teens. Six of us, three youths and three girls, all from the north-east of England, had decided to spend the last weeks of our summer holiday touring the country. In fact, touring is much too grand a word; we lived in a couple of ragged tents and moved from site to site in an old wreck of a car.

One of our stop-overs was at the beautiful little fishing village of St Ives in Cornwall. As always, my first stroll after setting up the camp was down to the sea. On a stone jetty I found a weather-beaten old man dressed in a navy blue jumper and crouching beside his fishing rod. As I approached he struck and reeled in a bright, silver fish of about three pounds. Although I had never seen one before, the captive was, unmistakably, a bass. My eyes devoured every detail of the old fellow’s tackle – the large pierced bullet, the three-foot trace, the long-shanked, wide-gaped hook and the plump six-inch sandeel still protruding from the jaws of the fish.

I struck up a conversation, as anglers do, and as a result was presented with a couple of sandeels for my own use. Within ten minutes I had collected my little solid-glass spinning rod and, with a rig identical to that of my new friend, I was casting out my bait from a stance twenty yards beyond his. To cut a long story short, I caught a single bass, a little smaller than the one I had first seen. I was firmly hooked by the gentle bite, the racing fight and the powerful, muscular, squirming silver body as I grasped the fish, removed the hook and returned my prize to the sea. No real angler could have resisted such a drama.

When I eventually moved to the south of England in 1965, bass became reasonably common catches for me but, in general, they were small fish (less than 3lb) and were taken by accident when fishing with worm baits for flounder or pouting.

The subsequent development of my bass-fishing experience is described in some detail in the book Operation Sea Angler. The essence of the story is the way in which, with the help of a few good pals, I explored (perhaps I should say ‘rediscovered’) the use of spinning methods to catch bass from the shore. The great breakthrough, as far as I was concerned, was the use of floating jointed plugs in shallow water over rough and snaggy ground.

On plugs, my mates and I have now caught bass of all sizes up to 12½lb. Despite now having landed hundreds of good bass I still look on any of these fish as beauties. I never tire of the heart-stopping thrill which attends the violent take of a bass on my lure.

As far back as I can now remember, most seasons have been blessed with at least some fish of over 8lb. On several occasions a number of fish between 8 and 10lb have been caught in quick succession on a single trip but a double-figure bass will always represent a red-letter day.

Most of my bass fishing sessions nowadays are of pretty short duration. By picking times and places carefully it is often possible, between May and November, to catch fish on the majority of trips, even fishing on average twice a week. As in any form of fishing, there is no magic formula for success. To catch fish consistently it is necessary to be adaptable. Although artificial lures are the mainstay of my approach, I am always prepared, when it is appropriate, to leger, float-fish or fly-fish with baits ranging from crab to maggots and from livebait to worms. My philosophy of bass angling can be expressed quite simply as ‘Look before you think and think before you fish’.

Flat Ledge – which accelerates the longshore currents and holds bass.

1

The Life Cycle of the Bass

The bass is a fish of slow growth. It attains a fairly large average size only because it appears to have a much longer ‘expectation of life’ than the generality of sea fishes.

Michael Kennedy, The Sea Angler’s Fishes, 1954

ML In the clear, cold waters of the English Channel, the first hint of the spring bloom of microscopic plants was staining the sea with a translucent, greenish tinge. The surface of the sea, untroubled by wind or rain, was swelling gently into deep oily dunes of water as it rounded the rugged, cliff-bound peninsula. As the tide began to flood towards the east, powerful eddies and surges broke upwards from the seabed pinnacles to boil on the surface of the race.

Half a mile north of the lighthouse, perched like a sentinel on the prominent rock, and twenty feet beneath the rolling swell, a school of grey-backed, silver-sided fish stemmed the powerful flow, seemingly with no effort. All the fish in the school were thickset male bass in the prime of life. The largest of them was over 8lb, but the majority were small fish of less than 4lb; all were now in breeding condition.

It was now the first week in May and the water was warm for the time of year. This followed a mild spell of weather which had lasted since Christmas. The male bass had been shoaled up, patiently waiting in the tide race, for almost two weeks. They fed, when the opportunity arose, on scattered shoals of tiny sandeels.

Suddenly a sense of excitement rippled through the assembled fish as a group of grey shapes loomed up from below. The largest of these newcomers was well into double figures and their flanks bulged with eggs, accumulated in the summer of the previous year. The excitement rose as the females entered the shoal and the male fish jostled and pressed around them, mouths agape and bodies quivering as their milt was released. Streams of tiny amber eggs issued from the hen fish and most of them were fertilised as they dispersed and drifted slowly up towards the surface of the sea. As quickly and as silently as they had arrived, the larger bass disappeared and the shoal of males settled once more to their silent wait.

In the following four or five days the fertilised eggs were carried to and fro on the tidal streams. Many of them became suspended in the cycling currents over the banks of shell-grit which lay on either side of the race. The vulnerable microscopic amber beads fell prey to a host of tiny, transparent, pulsing jellyfish, bristly, twitching copepods, fierce, spiky crab larvae and the fry of lesser fish such as rocklings. As the eggs drifted, they developed within them muscles, bones, nerves and little black eyes. By early June the tiny fish were visible, curled tightly inside their protective membranes.

As the bass larvae, each sporting a little sac of yolk, burst from their eggs, the fluid released by their escape attracted a further host of mini-predators. The stinging, thread-like tentacles of jellyfish entrapped countless young fish. Others fell victim to the shimmering comb-jellies. Glued to the branching, trailing, elastic filaments of the predators they were, one after another, reeled in and stuffed into wide-stretched mouths. Within the transparent bodies of the comb-jellies they joined their fellows, already crammed like little sardines, inside the bulging guts of their captors. Arrow worms, like vibrant slivers of glass, bristling with sickle-shaped jaws, lanced into the huddles of baby fish.

The surviving bass larvae were almost capable of swimming now, feeding on tiny pinpoints of marine life, too small and slow to escape even their feeble movements. Those which were lucky enough to encounter rich patches of food were growing quickly. Others, less fortunate, starved or died of disease. Four weeks after hatching many of them were swept close inshore by warm onshore breezes, in through the stone-flanked mouth of the harbour and into the torrent of salt water flowing in the narrow channel which led into a huge, shallow lagoon beyond. As they were swept along in the strong flow, many of them fell prey to the clumsy lunges of last year’s young pollack.

The most advanced larvae were already developing tiny scales as they swam about in tight little shoals over the shallow, eel-grass-clothed mud flats. The smaller specimens were mopped up by hordes of greedy gobies, with pop-eyes and rubber-lipped mouths, always on the look-out for an easy meal. The surface of the mud was a meshwork of lethal tentacles fringing the discs of burrowing anemones. Along with the bass, young sand-smelts and mullet were trapped, stung and swallowed.

As midsummer came and went the shallows warmed up, reaching 25° or 30°C on the hot sunny days. The young bass, now over an inch in length, prepared actively for the coming winter by consuming countless mysid shrimps, beach fleas and other small crustaceans, on which they pounced with typical bass-like ferocity. As they grew bigger, their diet changed to include larger marine slaters and burrowing sandhoppers (Corophium), which lived in little U-shaped tunnels near the high water mark.

The young bass spent their first winter in tidal channels sculpted by the run-off of water from the mud flats. In the next couple of years they fed, and grew fat, on the ragworms, crustaceans and midge larvae (bloodworms) swarming in their countless millions on the rotting eel-grasses which represented the rich, organic crop of the lagoon.

Some of the young fish had the good fortune to inhabit areas where the natural heat of the sun was supplemented by a flow of warm water from the cooling system of a power station. Even in winter, when ice fringed the mud flats, these lucky little bass continued to feed and grow more or less throughout the cold season, becoming nearly double the size of their siblings by the following year.

The power-station outfall, with its strong-flowing sources of heated salt water, provided the school bass with an almost ideal place to live. Injured and helpless prey animals, drifting along in the swift flow, were easy meat for the streamlined little predators. Boulders introduced to absorb the energy of the flowing water provided a haven for small shrimps, prawns, sandhoppers and slaters, which the bass nosed out and devoured. The warm water encouraged settlement of drifting larvae and enhanced the growth of ragworms, ‘snails’, crabs and similar prey. Bass of three or four inches long, now about one year old, fed very heavily on brown shrimps and mysid shrimps.

The young bass, like all young animals, were vulnerable to many predators and natural disasters. Lots of them perished when they were trapped on the intake screens of the power-station, particularly in the autumn, when they were close inshore. In winter many of them moved seaward so that fewer of the little fish turned up amongst the rubbish on the screens but, where temperatures were higher due to the inflows of warm water, the little fish were inclined to stay put throughout the year.

Predatory plankton animals which take a heavy toll of tiny bass.

During their first years the weather had been kind and more young bass than usual had survived the vagaries of the climate and the predation of many enemies. In the following years the young bass devoted their energies to feeding and growing. Then, between the ages of five and six, when they were just over one foot in length, the male fish became mature. The females matured when they were a little older and a little larger, perhaps fifteen inches in length and seven years of age. After they reached maturity the fish bred every year and in every spawning season each female laid her eggs in several batches.

After spawning, the adult fish fed actively throughout the summer and autumn months, until shortening days and falling water temperatures drove them to migrate towards the south and west and to settle for the winter in offshore resting areas until increasing day length and rising temperatures stirred them into another cycle of migration, breeding and feeding.

This then is the life of the bass, as we understand it at present. In British and Irish waters their feeding and growing season is quite short and, as a result, it will probably take twenty years for a female fish to reach a weight in double figures; male bass are slightly slower-growing and rarely exceed 8lb in weight. In warmer waters off the French coast growth rates are similar, but further south, along the Atlantic coast of Morocco, a fish of 10lb will typically be only twelve or thirteen years old. On a day-to-day basis sea temperature is important in the way it affects feeding activity and, consequently, the growth of bass.

The history of every individual fish is recorded in its scales and bones. The principle is exactly the same as the well-known method of counting the rings in tree trunks to read the age of the tree. Not only do the number of rings (annuli) allow us to estimate the age of a fish, but there is much more we can learn from bass scales.

Scales from a bass caught in 1985. The fish was spawned in 1976 and nine annuli (annual rings) can be clearly seen.

It is worth saying a word or two about the growth of scales themselves. When a young bass hatches from its egg it has no scales, and it is only a month or so later that the armour plating begins to develop. The first tiny scales appear on the flank, just by the tip of the pectoral fin, so these are the oldest scales and therefore the best guide to the age of the fish. As a bass goes through its life it gets knocked about by waves, rocks, predators, territorial battles or encounters with nets, anglers and other hazards. These scraps and scrapes may dislodge scales from the body. When new, replacement, scales grow to patch up the damaged areas they have no rings in the central zone, which looks distinctly rough and fuzzy. Such ‘repair’ scales cannot, of course, give a full record of the fish’s age, so several scales are needed from each bass to ensure that one or two good ones are obtained for reading.

Not only do scales reveal the age of a bass, but in warm summers when food is plentiful, the fish and its scales will grow quickly, producing a wide space between successive rings Following a bad year, of course, the rings will be close together. The edge of the scale represents the time when the fish was caught so, by working back towards the centre, it is possible to determine how much the bass grew in each year of its life. All fish and scales grow a little less in length with each succeeding year, so the spacing of rings near the edge of the scale will always be much less than near the centre.

So what? When you are sitting it out and waiting for a bass to take your carefully placed and presented peeler crab, does it matter how quickly the fish which you are not catching grew five years ago – or, indeed, at any stage in its life? Perhaps not, although it is interesting to look at scales, or alternatively the bones of the gill cover (operculum), of a particularly plump or emaciated fish to check on its recent growth.

The opercular (gill cover) bone of a sixteen-year-old, 7½lb bass.

Much more important than just satisfying the angler’s curiosity, is the scientific value of the accumulated knowledge from scale readings of many fish. It soon becomes obvious that fish born in a particular year are more abundant than those born in other years. From this it is clear that the number of recruits (survivors of the year’s crop of eggs) is occasionally much greater than usual. In fact the bass in British waters, because it is at the northern limit of its range, often has spawning failures and only when everything comes together do we see a strong year class.

Just as in the case of the American striped bass, all the evidence suggests that our bass stocks are in overall decline. However, this decline can be temporarily reversed by an unusually successful breeding season. One such successful year was 1959, and an exceptional number of bass were spawned and survived from that season. These fish then provided sport for about twenty years, though unfortunately they are likely to be all but vanished now. 1949 was another very good year. We can but hope for more years like these, and when they arrive, we must take every opportunity to protect and conserve these beautiful fish so that our children and grandchildren can enjoy them as we do.

2

Food

If the bass are feeding on 1½-inch whitebait I do not expect them to take readily a 3-inch artificial.

P. Wadham, B.S.A.S. Quarterly, 1921

ML The baits used for bass are well known, so why bother to look at what bass normally eat? There are several good reasons for this. First, by knowing where and when particular foods are likely to be available, we can choose the best bait and presentation for each fishing session. Second, there is no doubt that conventional baits and lures have limitations and the basis for improvements has to be in the natural diet of the fish. Last, in selecting venues, fishing spots, positions and even stances, a knowledge of the basic behaviour of food items can be invaluable.

Table 1 lists bass stomach contents as recorded by several different anglers. These lists show better than any other information how bass change their feeding habits from one place to another. After a look at what the fish actually eat, a short description of the natural history of many of these creatures should help us to decide where and when the bass will expect to find them.

Before we go on to consider the tables, bear in mind that an angler using a particular bait is to some extent selecting fish which are hunting for that type of food. Despite this problem, there can be little doubt that the bass in different places are accustomed to eating different proportions of the various food items.

There will also be a certain amount of geographical variation in the type of food available. A fish which is patrolling the north-western limits of bass distribution along the coast of Lancashire or Cumbria will not encounter the same variety of edible animals as one around the rocks of Land’s End or one at the other extreme of decent bass fishing in the southern North Sea.

The picture which emerges from Table 1 is tricky to understand.

Table 1 Stomach Contents of Rod-caught Bass

The numbers show how many bass contained each type of food.

Other samples of fish from the Dorset coast showed that occasionally the bass had been feeding intensively on a single type of food. At times, sea slaters were the only food present in dozens of fish caught. Kennedy and Fitzmaurice give an extensive list of bass gut contents from south-west Ireland. Shore crabs were noted to be the most abundant items and, apart from a wide range of fish species, hermit crab, swimming crab, shrimp, prawn, slater, squid, cuttlefish and octopus were recorded from the stomachs of the Irish bass. Crabs, of various sorts, are always well represented in bass food and obviously they are important. However, crabs are pretty tough, shelly creatures and may resist digestion for quite a time. There are no studies on bass digestion, but scientists working on other species of fish have shown that crab may last several times as long as fish in the acids and enzymes of a fish’s stomach. So it is quite likely that more fish are actually eaten than the table suggests – perhaps at least as many fish are eaten as crabs in most cases. By the same reasoning, other soft foods like worms may be a bit more popular with the bass than they seem.

Although crabs and fish make up the bulk of a bass’s diet, there are quite striking differences in detail. In the Menai Straits edible crabs loom large; in south-west Ireland, Cornwall and the Isle of Wight shore crabs were the main crustaceans; while in south Dorset, although shore crabs were abundant, edible and velvet swimming crabs were also very well represented.

Whereas in Cornwall sandeels were the main fish eaten, in other places different species predominated – wrasse in the Isle of Wight, flatfish in the Menai Straits and south-west Ireland and a wide range, including rockling, pipefish and sea trout in south Dorset (seeTable 2, page 25).

In addition to these major foodstuffs, there are some surprising features. In Dorset maggots (of the seaweed fly) were often eaten in large quantities. In Cornwall sandhoppers were consumed by a fair number of the bass examined. In the Isle of Wight cuttlefish were sometimes important and in the Menai Straits and south-west Ireland shrimps and prawns were eaten. In Dorset and south-west Ireland slaters fell prey to the bass in great numbers.

Obviously, the larger bass eat other fish and various crabs when they can get hold of them and this should be (and is) the basis of most of our fishing methods. However, bass are clearly opportunists in the sense that if any sort of creature becomes available in large quantities they switch on to that food. The really successful bass angler must also be prepared to switch when he needs to – whether the groundbait is natural, such as maggots, slaters or hoppers, or less natural, such as fish offal, bread or cheese.

CRABS

Hard crabs are the items most frequently found in the guts of decent-sized bass. Although these crusty mouthfuls are good baits for wrasse (ballan and corkwing), and are often used for this purpose, few bass are caught on them. Frequently bass must be present in the areas where anglers are fishing for wrasse with hard-crab baits, but rarely, if ever, do they seem to have a go.

Crabs eaten by bass include the well-known shore crab (Carcinus maenas), the edible crab (Cancer pagurus) and the velvet swimming crab (Liocarcinus puber). These are by no means the only crustaceans which bass find tasty. The list is quite long. Small swimming crabs (Macropipus depurator), which are often abundant in offshore sandy areas, frequently occur in guts. Burrowing masked crabs (Corystes), squat lobsters, sea slaters, spider crabs, prawns, shrimps, lobsters and hermit crabs are also eaten by bass from time to time.

Above left: edible crab. Above right: velvet swimming crab. Below: shore crab. These are the most useful crabs for bait.

Why then should soft or peeler crabs be such outstanding baits? All crustaceans grow by moulting their shells when these become small and cramped. Moulting or ‘peeling’ occurs more frequently when they are young, when the weather is warm, before they are due to mate (males) and at mating time (females). At all of these times the crabs will be extra vulnerable because, for various periods:

1. They will be inactive (easier to catch).

2. They will be less aggressive (easier to deal with).

3. They will release ‘moulting fluids’ (be easier to smell).

4. The new (soft) shell will leak (be easier to smell).

Mature crabs can mate only when the females are soft-shelled. Many species have a rather short breeding season, when peeling and soft females are plentiful.

The pattern Alan has noticed each year when collecting shore crabs is that in April and May there is an increase in the number found and most of them are males; shortly afterwards they peel. Later on in May or June the females appear and peel. Then many pairs of crabs are present, making bait gathering easier. At this time it is rather unusual to find females unattended by males, unless they are carrying eggs. As the season progresses, crabs of both sexes are found separately on the shore and some may be peeling or soft. There seems to be a second peeling season for male shore crabs at the end of the summer (late August and September) on some stretches of coastline.

Although young shore crabs probably moult several times each year, the mature animals shed their shells only once annually, living for five or six years. It seems likely that males are attracted to females by some chemical attractant, but so far scientists have been unable to detect one. Some moulting shore crabs are usually present on the shore at any time of the year, but there are very few to be found in the winter.

Edible crabs follow a similar pattern, but the larger specimens, which migrate extensively during the year, first appear on the shore a few weeks later than the shore crabs. Again the males peel first and afterwards the females are usually the bait collector’s reward throughout the summer up to September or October, depending on locality.