Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

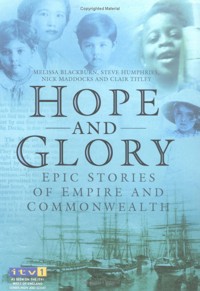

Hope and Glory and the television series it accompanies provide a unique record of the strong links between the West of England and the Empire and Commonwealth in the twentieth century. It features the epic stories of men and women whose lives were shaped by emigration and immigration on an unimaginable scale. We hear the voices of those who were inspired to undertake a life-changing journey across the sea to England, to Australia, to India, Africa and the Far East. What was it like to grow up in India at the height of British Empire? What happened to the thousands of orphans forcibly transported to places like Australia and Canada? How did it feel to struggle for civil rights in 1960s Bristol? What was it like to be an eighteen-year-old National Serviceman fighting a war in the jungles of Malaya? Hope and Glory is a fascinating and often moving snapshot of a bygone era whose legacy lives on today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 244

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2004

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HOPE

AND

GLORY

EPIC STORIES

OF EMPIRE AND

COMMONWEALTH

HOPE

AND

GLORY

EPIC STORIES

OF EMPIRE AND

COMMONWEALTH

MELISSA BLACKBURN, STEVE HUMPHRIES,

NICK MADDOCKS AND CLAIR TITLEY

Melissa Blackburn is Associate Producer of Hope and Glory, and principal author of this accompanying book. Nick Maddocks is Producer/Director of Hope and Glory and has worked on a number of series for the BBC, ITV1 and C4. Clair Titley is an award-winning graduate of UWE, and Hope and Glory’s researcher. Steve Humphries is Series Editor. He is the author of over twenty social history books documenting life in twentieth-century Britain, many of them written to accompany television series, including A Secret World of Sex, The Call of the Sea and Green and Pleasant Land. He set up the independent TV production company Testimony Films in Bristol in 1992.

First published in the UK in 2004 by Sutton Pubkishing

This book is based upon the ITV1 West of England television series produced by Testimony Films.

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

Copyright © Melissa Blackburn, Steve Humphries, Nick Maddocks and Clair Titley, 2004, 2013

Melissa Blackburn, Steve Humphries, Nick Maddocks and Clair Titley have asserted the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9524 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

Dedicated with love to Barbara and Robert Blackburn

Contents

Acknowledgements

ONE

Memories of Empire

TWO

Daughter of India: Hazel Hooper

THREE

Escaping Apartheid: Precious McKenzie

FOUR

Out of Africa: Rosalind Balcon

FIVE

A Stolen Child: John Hennessey

SIX

Leaving Hong Kong: Rosa Hui

SEVEN

A Marriage in Malaya: Alice Harper

EIGHT

War in the Jungle: Alan Chidgey

NINE

A Journey across the Sea: Roy Hackett

TEN

A Passage to England: Mohindra Chowdhry

ELEVEN

Love Down Under: Sheila Mitchell Bane

TWELVE

Making History

Notes

Further Reading

Oral History Resources

Picture Credits

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to James Garrett at HTV, for believing in the project and supporting it. Thanks also to Ifty Khan and Margaret Whitcombe at HTV for their expertise and advice. We are also grateful to Gareth Griffiths, Mary Ingoldby, Ben Woodhams, Faisal Khalif, Jan Vaughan and Jo Hopkins at the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum for all their help and insight.

We would like to thank the contributors to this book for sharing their experiences and for their time and endless patience: Rosalind Balcon, Sheila Mitchell Bane, Ben Bousquet, Mohindra Chowdhry, Alan Chidgey, Roy Hackett, Alice Harper, John Hennessey, Hazel Hooper, Rosa Hui, Norman Jones, Precious McKenzie, Alok and Priti Ray and Sadie Regan.

Thank you to Richard Clutterbuck, Jill and Ivor Maddocks, Madge Dresser, Cluna Donnelly and the Malcolm X Centre’s Elders’ Forum, the Bristol Record Office, Joe Short and especially Matt Coster.

Finally, thank you to all at Sutton Publishing, from all of us.

Hazel Hooper in December 1926.

ONE

Memories of Empire

This book uses living memory to explore the close links between the south-west of England and the British Empire and Commonwealth in the twentieth century. Incredibly, at its height between the world wars, Britain ruled a quarter of the globe and 600 million people. But while its size and power still inspire awe, many people see the heyday of empire as a deeply shameful period: Britain’s massive complicity in the slave trade, its economic exploitation of its subjects, its bloody enforcement of British rule and its practices of racial discrimination and segregation are appalling to us today. However, others point to a more beneficial legacy, to an empire that hungered for trade but that also spread liberty, prosperity and the English language around the world. What is not in doubt is that the British Empire was the biggest empire the world has ever seen, and it shaped the world we live in today more than anything else in the last 500 years. Documenting its history is vital to our understanding of our present and our future, and this was the inspiration for Hope and Glory and the six-part television series it accompanies.

The original idea for this project came from a display we made for the recently opened British Empire and Commonwealth Museum in Bristol, whose twenty permanent galleries span 500 years of the history of the British Empire, from its rise through trade and colonisation, to the height of British rule in the Victorian and Edwardian eras, to its final demise. In the last gallery, the museum planned to use its huge oral history archive as the basis for a video display that would allow people whose lives were shaped by the empire and commonwealth to tell their stories. For the museum, oral history opened up the past in a way that facts and figures could not: it could help to unravel the complicated history of the British Empire by giving people the freedom to tell their stories their way and so create a more human picture of history. They hoped that this kind of first-person, eyewitness testimony would give a voice to those hidden from history: ethnic minorities, impoverished migrants and refugees and the women of empire, offering a more complete and vivid picture of the rise and fall of the British Empire in the twentieth century.

In a series of dramatic personal journeys, those who went out to live in the old empire are captured on film telling their stories alongside those who came to Britain from the former colonies. The video display features people from all over Britain, among them Ben Bousquet, a West Indian elder who speaks passionately about his experience of migration to England:

I’m from St Lucia. I came to this country when I was sixteen years old in 1956. I was often humiliated by people stopping me, and asking me if I had a tail. They wanted to touch my tail. They wanted to rub my skin on Christmas Day. They thought that would bring them luck in the coming year. They knew nothing about us and about the Commonwealth and what it was meant to be all about. We knew more about the English than the English did.

The British Empire and Commonwealth, seen here in 1944, was the biggest empire the world has ever seen, reaching its height in the 1920s and 1930s. It covered 25 per cent of the globe, colouring every schoolchild’s map a dark pink; it stretched out across the dominions of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa; it included large parts of southern and western Africa, as well as the old slave-trading colonies on the east coast; and it engulfed the huge Indian subcontinent and parts of South East Asia including Malaya and Hong Kong and the islands of the West Indies. In all, between the two world wars, the population of Britain’s Empire and Commonwealth numbered six hundred million. Even today, the Commonwealth’s fifty-four ex-colonies, with the Queen as their nominal head of state, make up a quarter of the world’s population.

A plan of a slave ship. Between 1685 and 1807 about 2.8 million slaves were taken from Africa by British slave-traders, with Bristol taking a fifth of these. Over 2,000 ‘slaver ships’ made voyages from Bristol’s docks during this time. There was little slave trading in Bristol, because slaves were mostly sold in the Caribbean and America, and in fact by 1772 it was illegal to force slaves to be taken from the UK. But the practice continued, with the writer Hannah More witnessing the seizure in Bristol of a black woman who had run away because she did not want to return to the West Indies: ‘The public crier offered a guinea to any one who hunted her down, and at length the poor trembling wretch was dragged out from a hole in the top of a house, where she had hid herself, and forced onboard ship.’

Tobacco was part of Bristol’s economy until comparatively recently. It came from the colonies of Maryland and Virginia, and by the end of the seventeenth century Bristol was handling millions of pounds in weight of tobacco. Advertisements like this were common, depicting the children of black slaves who laboured on the plantations.

Mr Chowdhry, a Sikh resplendent in a colourful turban who came to Bristol from India, describes falling from a crane 100 feet up into the Avonmouth docks where he worked: ‘I had a dip and it drenched my turban!’ Miraculously he wasn’t hurt. ‘Coming to England was a fantastic journey for me; I’m glad I came.’

The display has been popular with the public, but we felt we had only touched the surface of a deeply complex and captivating history, and that there were many more stories to tell. We wanted to concentrate purely on those with links to the south-west, broadly defined as Bristol, Somerset, South Gloucestershire and Wiltshire. The south-west has strong links with the British Empire, especially through the trading port of Bristol and the large numbers of locals who left to live, work or fight in the old colonies. Similarly, the area is home to strong communities from Asia, the Caribbean and Africa, who arrived here as a direct result of the colonial experience. Because the history of the empire and commonwealth is so vast, the south-west gives valuable focus to a potentially unwieldy subject. Research for this new project began in the autumn of 2002, continuing through 2003. We contacted many local community groups, placed newspaper advertisements calling for people’s memories and sent countless letters and emails. We spoke to hundreds of men and women who told us their stories.

It became clear that many of their stories had an epic theme in common, one of the great themes of empire: the constant movement of peoples. This was no surprise. The rise of the British Empire and Commonwealth created the biggest mass migration in human history: between the early 1600s and the 1950s, more than twenty million people left Britain for the lands of empire. Some left in search of riches or power, others in search of religious or political freedom. Some were transported as criminals or indentured servants. Others were civil servants, engineers, soldiers, foresters or missionaries. Then again, since the 1950s more than a million people have come to Britain from the empire and commonwealth to live and work here as citizens, creating a new country where 300 languages are spoken and fourteen faiths practised. The south-west itself has been the scene of endless comings and goings, a gateway of empire for 500 years. While this book concentrates on its twentieth-century oral history, it is helpful to understand some of the forces of empire that shaped the south-west, and that affected the lives of so many of today’s locals.1

Five hundred years ago the city of Bristol was as central to the region as it is today. Clustered round the rivers Avon and Frome as they snake out into the huge estuary of the Severn, Bristol’s thriving port was in the centre of the city, where the tall ships seemed to sail through the streets, their sails and long masts glimpsed through the narrow alleyways. John Cabot’s epic 1497 voyage of discovery to Newfoundland lit a fire in every Bristol merchant’s heart, and from then on the city was powered by trade with the New World. It would have been a noisy, bustling place, its ships heading out to the plantations of the newly claimed colonies of Virginia, Barbados and Jamaica, carrying British goods and plantation workers – the very first emigrants of empire. However, the burgeoning British appetite for new luxuries such as sugar, tobacco and rum soon created a corresponding thirst for manpower on the plantations. Although ten thousand Bristolians had emigrated by the end of the seventeenth century, many as transportees, white slaves or indentured servants, by 1650 the public mood had turned against emigration, many feeling that it was weakening the country. This feeling was to last until about 1800, possibly because of rumours of the deadly heat, disease and primitive conditions in the plantations. Fresh manpower needed to be found, and, when the London-based Royal African Company’s monopoly on the British slave trade ended, Bristol merchants saw their chance.

The placement of Bristol port in the centre of the city and its tidal nature meant that it was often difficult for ships to navigate. With the invention of steamships new docks had to be built out at Avonmouth to handle the endless goods of empire that poured into Bristol.

Bristol’s slave-trading past is infamous: it was soon the second most powerful slave-trader after London, and there is no doubt that the prosperity of the entire south-west region was built on the lives of the half a million African slaves who were bought and sold by Bristol’s ships in the eighteenth century.2 Eventually Bristol’s share of the trade began to dwindle, but such was the city’s involvement in the trade that, when Wilberforce’s first Abolition of Slavery bill was defeated in the Commons, there were fireworks and cannons fired on Brandon Hill and church bells were rung across Bristol. But domestic pressure and increasing revolts on the plantations made abolition in 1807 almost inevitable, by which time Bristol’s direct part in the trade had declined to almost nothing. However, the imperial movement of people of which slavery was a part meant that there was a small black community in Bristol from the mid-seventeenth century, made up of black servants, slaves and nannies brought back by wealthy plantation-owners, Indian lascar sailors and black seamen and merchants.3

After Waterloo in 1815, Britain was established as one of the great world powers, with complete naval supremacy. Gradually the British dislike of emigration melted away, and was replaced with a new, Victorian obsession: the expansion of what was now called the British Empire. Hundreds of thousands flocked abroad, the Plymouth Times in January 1848 claiming that there were ‘forty single ladies for every single man in Weston-super-Mare’, as men left for work abroad in their droves. Although Bristolians were among the first convicts to be transported to Australia in 1787, by the 1840s the government was encouraging working-class emigration, and people from the south-west flocked to Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Fifteen thousand alone were taken from Bristol to Australia by the SS Great Britain in 1843. But again, not everyone went voluntarily. The Bristol Guardians sent batches of Bristol orphans over to Canada in the 1870s in order to buttress the population there. About 150 orphans were sent over a period of three years, and even back then there was a public outcry and the practice was stopped.4

Tall ships such as these resting in Calcutta’s docks around 1880 were the lifeblood of the British Empire. There are records of small Asian communities in Gloucestershire and Bristol from the eighteenth century, some of whom were lascars or merchant seaman and some of whom came to England to study law or medicine. Although most of Bristol’s trade was with America and the Caribbean, Bristol’s imperial links with India became much stronger in the nineteenth century.

The classic image of empire, such as this early photograph of the Raja of Suket in 1919, is of the pomp and circumstance of British India, the jewel in the crown of empire. Less than thirty years after this photograph was taken, India gained its independence and the British Empire began to topple.

By now Bristol’s skyline was crammed with glassworks whose cones were ninety feet high and soap-makers using the plentiful waters of the Avon. There were lead-smelters and brass works, giant sugar refineries and tobacco factories. The advent of steamships in the first half of the nineteenth century and the opening of Bristol’s new docks at Avonmouth brought yet more imperial trade to the city, and, after the monopoly of the East India Company had been broken, trade between Bristol and India began to flourish. Whilst thousands of Britons flocked to British India every year, there was a tiny trickle of Indians coming to the UK, most coming to attend British universities to study law or medicine. Rammohun Roy, often called the Father of India for his gentle and progressive nationalism, was one of the first Hindu Brahmin intellectuals to visit Bristol in 1833, and local ladies were apparently very taken with the tall, swarthy aristocrat. Sadly, after a sudden but short illness, he died and is buried at Arnos Vale cemetery. His death stimulated the social reformer Mary Carpenter to set up the National Indian Association to promote knowledge about India and understanding between Britons and Indians.

The Gold Coast had provided the slave ships with their grisly cargo, and it continued to provide Britain with the luxuries it craved. Here bananas are sold at a market in Ghana in the 1930s.

These lions were killed because they had been preying on local cattle in Kenya in the 1930s. The photo is by the writer and photographer Elspeth Huxley, who wrote a great deal about the British experience in Africa before the war.

By the turn of the century the might of the British Empire seemed unstoppable. The Great Coronation Durbar of 1903 celebrated Edward VII’s succession in New Delhi, and in 1904 the first Empire Day was celebrated on 24 May throughout the land and in every British colony. After the victory of the First World War, in which Britain was supported by nearly two million imperial soldiers, the British Empire was swollen with gains from the defeated German and Turkish empires. But, just as the empire reached its peak, cracks began to appear. Britain had already given Dominion status to Australia (1901), New Zealand (1907) and South Africa (1909), meaning that, although the king was still sovereign, national parliaments had the independence to govern themselves. These cracks were widened by local movements like Mahatma Gandhi’s increasingly popular passive resistance movement, which called for independence for India.

Nevertheless, the British Empire enjoyed its final heyday in the 1920s and 1930s, recent enough to be remembered by many people alive today. As the south-west began to recover from the Great War, the British flocked to the newly expanded empire, many in an effort to find peace after the horrors of the battlefield.

It was at this time that many of the people whose stories we feature in this book were born, Rosalind Balcon included. Rosalind’s father decided to emigrate to Kenya, partly because he was concerned that another war might be on the horizon, and she remembers the shock that she felt having to leave England: ‘It was pretty traumatic leaving because everyone had to say goodbye and we went down to the docks on a really miserable November day. But it was exciting too because we’d never been on a big ship before. We went on what we thought was the biggest ship in the world. I think it was 11,000 tonnes, which is now considered rather titchy.’

Hazel Hooper and her twin were born in England in 1922. Their parents took them back to India when they were six months old. ‘I suppose it was a way of life which I absolutely loved. In fact I suppose I loved India more than anywhere because I knew it better than anywhere. So perhaps it meant home, perhaps I didn’t realise we were the rulers. We’d never use that word, it’s only in history I’ve heard that word.’

However, for many people in India, the British were very much the rulers, and the growing disquiet even manifested itself in the south-west: throughout the 1930s Dr Sukhsagar Datta and his colleagues in the Bristol Labour Party were campaigning vociferously for Indian freedom. As Gandhi’s non-violent revolution gained pace, it was clear that British India’s days were numbered. The Second World War erupted, drawing in two million troops from the colonies and tens of thousands of soldiers from the south-west. The war was the death knell of empire, and by the end of it a weakened Britain was forced to admit America’s new supremacy and to give in to fresh and fervent demands for independence from its colonies. By 1947 India had gained independence and the country was split into Hindu and Muslim states, and the attempt to move millions of Muslims and Hindus to their newly allotted lands resulted in massive bloodshed. Priti Ray grew up in India but now lives in Bristol:

I was born in 1936 and grew up in West Bengal. The village I grew up in was self-sufficient and very progressive: it was almost completely Muslim, and we were Hindus, yet we grew up like a brother and sister. My father was a Gandhi supporter, and my grandma used to do the weaving and make all our saris and everything at home – we just boycotted all the British products. During the worst part of partition, we got all the women and children into our house and they stayed away from any trouble. And when the trouble was over after eleven days they went back. But it was a terrible time: so many people were chopped up. It was horrible.

Rosalind Balcon and her twin sister, with father and grandfather in the West Country in the 1920s. Rosalind’s father foresaw the coming Second World War, and felt that the family would be safer in Kenya. They emigrated in 1935.

For colonials like Hazel Hooper, who was later to settle in Bristol, it was devastating to be forced to leave India, but she was comforted by the belief that England’s influence had been beneficial: ‘We had left India a good legacy, because the universities and the schools were started or begun by English people. The hospitals, the railways system, which they say is about the best in the world. Although it’s not run by Englishmen, we began it. And also, the English language, which they all learnt, all over India, and now that means Indians can go all over the world.’ She became one of millions heading back to England as empire disintegrated, to a country that was very different from the one she’d been born in, to start a new life.

Still, people continued to emigrate, willingly or unwillingly. John Hennessey, who grew up in an orphanage in Bristol, was one of tens of thousands of ‘orphans’ who were sent out to Australia, Canada and South Africa in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. Although public anger had temporarily stopped the practice in Bristol in the 1870s, it continued into the twentieth century and emerged with renewed energy after the Second World War. The aim was to bolster the white populations of the colonies. As the Archbishop of Perth, Australia, said to the young boys and girls arriving on ships from Britain in 1938: ‘At a time when empty cradles are contributing woefully to empty spaces, it is necessary to look for external sources of supply. And if we do not supply from our own stock, we are leaving ourselves all the more exposed to the menace of the teeming millions of our neighbouring Asiatic Races.’ The Australian government asked its British counterpart to send out more British children to increase the white population. The call went out to churches and their agencies, with the Catholic Church being a particularly enthusiastic supporter of the initiative. The falsification of birth certificates and emigration documents was common, and the children were told that they had no living relatives left in Britain and that Australia was now their home. But this was often a lie. Most of the children were not orphans, but had been removed from their parents illegally: 87 per cent of all children from Catholic agencies came to Australia without the consent of their parents, and 96 per cent of those sent had one or both parents alive. The practice stopped in the late 1960s when they simply ran out of children to send, and it was decades later that the harsh conditions and abuse that many of the children had experienced were exposed.

Hazel Hooper as a baby with her twin sister and elder brother, with their Indian servants at their house in Madras, 1923.

These ‘orphans’ are on a train bound for Southampton, from where they’ll be transported to Australia. Over 150,000 orphans were sent out to Australia, Canada, Zimbabwe and South Africa to boost the white population – but, unbeknown to them, many had parents still living in Britain.

At the same time as the orphans were shipped off to an uncertain future, Britons were being encouraged to emigrate to Australia as part of the ‘Ten Pound Pom’ scheme. It offered a cheap (£10) boat fare to Australia in the hope, again, of building up the country’s white population, and for many south-west families it was a sunny, over-the-rainbow dream.

For newly divorced Sadie Regan, living in a terraced house in Avonmouth with her new husband Johnny, the scheme offered a fresh start away from the prejudice that divorced women then faced. By 1965 the couple were living near Brisbane with their three children: ‘We were allocated a hut on an ex-military barracks, with the most basic of furnishing requirements. We met lots of friendly people from the UK, but not everything was wonderful of course. Mosquito nets were an essential protection from the ever-present mosquitoes, which loved to feast on the blood of freshly arrived Europeans!’ Eventually they bought a house. ‘It was a beautiful house with a yard like the Garden of Eden – banana trees, choco trees, figs. But when it was time to cut down the huge bunches of bananas, my husband got a shock. Tarantulas came out of every hand of fruit – first the parents, an enormous female the size of a mouse, and then millions of young ones! I had to hose him down and force them off him.’

For many Ten Pound Poms, however, leaving Britain meant not just the promise of a new life, but the pain of being parted from family and friends, possibly forever. ‘One day, I got a call from my sister telling me our dad had died,’ recalls Sadie. ‘I was very sad, because I had adored my parents, particularly since they adopted me when I was six weeks old. I prayed hard that he and Mum were resting together.’ When her husband’s stepfather died a few years later, he began to worry about how his mother was coping back in England. After six years of adventure, hardship and sunshine, the family decided to come home.

Sadie Regan with her husband, before they emigrated to Australia.

As empire fell apart in the 1950s and 1960s, the south-west experienced new waves of emigration and immigration. While the foot soldiers of the British Empire – its bureaucrats, officers and managers – came home from India, and new independence movements gathered pace in Africa and the Caribbean, the British government was calling out to the colonies to come and help rebuild war-torn Britain. There had been a very small black population in Bristol for hundreds of years, but in the 1950s government-sponsored Caribbean workers, some of whose ancestors were the African slaves who had helped build Bristol’s prosperity, began creating a strong black community for the first time. For many, their first experience of the motherland was disappointing. The cities of the south-west – Bristol, Gloucester, Bath – had been badly bombed and first impressions were of poverty and dilapidation. It was often in the most run-down areas of the city, like St Paul’s in Bristol, that the new arrivals were forced to make their homes. The cold, too, bothered many. But the racism and segregation that had often characterized the colonial experience, and that had arguably begun with the switch to black slavery, were a shock to these sons of empire, who considered themselves British and who were here to help rebuild the south-west. The experience of Roy Hackett was typical.

It was a very raw reception. It was not very friendly. It was not a welcoming one.… I had lived in Jamaica all the time amongst white people and I never thought that I was any different from them. When I came here I did see the difference. Because I was put in my place that I was black, that I was a nigger, and it made me very ashamed of even being British, actually.

Man walking through St Paul’s, 1960s. Although encouraged by the British government, who were desperate for help in rebuilding war-torn Britain, many Caribbean immigrants encountered a disappointingly cold and unwelcoming reception.

A man putting out a flag in St Paul’s, 1960s.

Alok and Priti Ray around the time they first came to England in the early 1970s.