Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Beata & Horacio Cifuentes

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

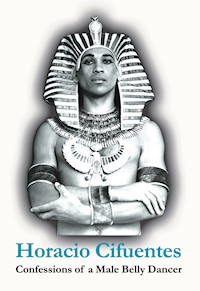

Born in Colombia, South America, Horacio Cifuentes attended various dance academies in Spain, Poland and the United States. Among them, the prestigious American Balet Theatre School and the San Francisco Ballet School. Michael Smuin, director of the San Fransisco Ballet discovered Horacio and featured him in various key roles in the dance company, where he also worked with international choreographers such as Jiry Kylian, Robert North and Arthur Mitchell. Horacio was inspired by American bellydance pioneer Magana Baptiste to become an oriental dancer. Under her guidance he followed extensive studies into the mystical world of yoga, spiritual dance and belly dance. His story is full of fascinating anecdotes, humor, tragedy and brings with it a profound spiritual depth. Horacio Cifuentes resides in Berlin, Germany, where he co-directs a dance academy with his wife and dance partner, Beata Cifuentes.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 315

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HoracioCifuentes

Confessions of a

MaleBellyDancer

CONTACT:

Beata&HoracioCifuentes Tanzakademie Cifuentes

Nürnbergstr. 37 14547 Beelitz. Tel. 0176 834 68674

[email protected]·www.oriental-fantasy.com

HoracioCifuentes

Confessions

of a

MaleBellyDancer

Beata&HoracioCifuentes

Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: DieDeutscheNationalbibliothekverzeichnetdiesePublikationin der Deutschen Nationalbibliogafie;detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar.

ISBN978-3-00-027042-0

©2009Beata&HoracioCifuentes,Berlin/Germany

www.oriental-fantasy.com

Layout:TanzakademieCifuentes,SabrinaLau

Druck:Buchdruckerei24.de,Plauen/Germany

Edited by Don Klein

Photos:

Cover:DonKlein

William Acheson (page 94), James Armstrong (p. 78, 89, 115, 116, 117), Magana Baptiste (127, 129 bottom), Fred Baumgart (p. 148, 151 bottom), Michele Dearborn (p. 136), Hans Faun (p. 149, 156 top), Vitali Garelev (p.150bottom),HiromiGoto(p.179),HurEunSook(p.150 top),DanielaIncoronato(p.137,151 top,155, 157 bottom, 158, 159, 214), Don Klein (p. 98, 111, 121, 130, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 163,

182,191),KranichphotoBerlin(p.215),kuvagalleria.net(p.152,153,154,160),BobMcLeod(p.77top),

Peggy Meyers (p. 170, 171, 172), Russell Murphy (p. 131, 132, 133, 134, 135), Youssef Nabil (p. 157 top), Klaus Rabien (p. 156 bottom, 200, 206), Werner Salomon (p. 122 top), San Francisco Ballet (p. 77 bottom), SanFranciscoExaminerImage (p.147),MartySohl(p.92,104),JohnvanLund(p.66),otherphotos:private collection

AllillustrationsbyHoracioCifuentes

Acknowledgements:

Thereareseveralindividualswhocontributedgreatlytotherelizationofthisbook.

First and formost I wish to thank my dear and life-long friend Don Klein. His wisdom and precious advice have been of inmeasurable value. Above all, I thank him for his friendship and support throughout my life. Hisfriendship,evenatlongdistance,representsapillarofstrengthandsupportforme.Akindoffriend-

shipanyonecanfeelfortunateandprovilegedtohave.

I wish to thank my dearest dance teacher Magana Baptiste. Her beauty and spiritual greatness inspired me tobecomeanorientaldancer.Herkindwordsgracetheforewordinthisbook.Herguidanceisasubstan-

tialpartofmydailyliving.

IwishtothankmydearfriendDr.WadeSmith,whoprovidedenlighteningobservationsregardingthe

essenceofthestory.

IkindlythankmyfriendLauriLehmann,forhisinputandintelligent comments.

Ialsowishtothankourassistant,SabrinaLau,forhertirelesswork.

Lastbutnotleast,Iwouldliketoexpressmygratitudetomylovelywife,bestfriend,accomplice,andcom- panion through this time-tunnel we call life, Beata Cifuentes. Her wise advice and perceptive observations

havebeengreatlyinstrumentalinthe completionofthis work.

DedicatedtotheDivine–

theall-seeing,all-loving,andall-knowing,

whoknowsthatmy story istrue

and

to Beata

Foreword

byMagana Baptiste

W henKyraNijinsky,daughteroftheimmortalVaslavNijinsky–consideredthe

world’sgreatestdancer,firstsawHoracioCifuentesdanceatmydancestudioin SanFrancisco,sheexclaimed,“heistheNijinskyofOriental Dance!”

To write of Horacio is to write about a Renaissance man. He is an inspiration to all who see him, whether it be oriental dance, ballet, or Spanish and international dance – and the Spiritual Yoga dance.

This book conveys fascinating details of his experience in all these movements and disciplines.

It is valuable in so many ways. His beginnings as a boy in Colombia, South America; his first ballet lessons; his dedication; his will; his passion for the dance; his disappointments and his triumphs. He suffered prejudice and discrimination for his dance skills, for being eccentric, for his color and the many jealousies because of his great talent.

This memoir has much humor – just his experience with the Egyptian dance and music community and the temperamental divas. Also, there are many exciting details of backstage rivalries, romances, tragedies and triumphs.

We are taken into the fascinating and dangerous world of his experiences with drugs and psychedelics.

Fate intervened and his whole life changed when he was discovered by Michael Smuin, the great director and choreographer of the San Francisco Ballet, who instantly recognized histalent and signed him to a contractwith San Francisco Ballet. Fromthat time on he was taken into the world of the superstars and great teachers of the ballet world in New York and San Francisco – into his rise as a superstar himself.

The book has so many valuable insights into the training and discipline, and the difficulties encountered in his spectacular career. His description of his many illustriousteachersis most entertaining and especially instructional for the dancer.

He writesofhisinsightsintothe artofthe danceand yogaasa spiritual discipline. In the years of 2006 and 2007 there has been a phenomenal rise in the popularity of yoga – worldwide hundreds of millions of practitioners. Not so when my husband and I founded the first center of yoga in San Francisco and the West Coast.

Yoga,then,inthe1950’s,wasconsideredstrange,andinterestwasaslowprocessofpioneering.

Horacio’sexpertiseinyogacamebecauseofhisstrictpracticeanddiscipline–adiscipline in the path of yoga under instruction and initiation supervised by the great spiritual master and his Guru, Walt Baptiste.

IfirstmetHoracioatourYogaCenterwherehetookhisdailyyogaclasseswithWalt

Baptiste.AfterhissessionshewouldcomeupstairstothedancestudiowhereIwasteaching Middle Eastern Dance (popularly known as belly dance) and watch the classes – fascinated by he dance and the music.

Iencouragedhimto comeinto theclasses andstudythedancewith us.I amproud thatI

washisfirstteacherinthisAncientClassicalDanceForm,“TheDanceOriental.”

Anotherjewelinhis crown was hismarriagetothebeautifulBeata–aperfectpartnerfor

Horacio’sdanceactivitiesandtheSpiritualLifeasTeachers,Performers,andDancers.

His Spiritual Master WaltBaptiste married them in the Conservatory of Flowersin Gold- en Gate Park, in San Francisco, California.

Horacio’sbookisaGEMandshouldbeoneveryone’sbookshelf.

AtrueMasteroftheDance,heknowswhatofhe speaks.

MaganaBaptiste,SanFrancisco2007

INTRODUCTION

The day after a successful performance of Oriental Fantasy at Berlin’s Tempodrom in 1992,Iwasstandinginlineatafruitstand.Theplacewasfullofcustomersandthe linewasratherlong.Suddenly,amaninaloudvoicesaid:

“Youarethatbellydancer,aren’tyou?Thatguywhohasbeenfeaturedinthepapersre-

cently–that’sright,youarethatbellydancer!”

Allheadsturnedtowardsmeandtheexpressionon theirfacesseemedmeanttomakeme ashamed of myself.

By then I had developed an aversion to the term “belly dance.” I prefer to call myself an oriental dancer – actually it’s classical term. But then I would have had to explain what oriental dance is and people would always ask, “is that belly dancing?”

It seemed impossible to get away from that name, the stereotypes and the pre-judgment as well as misconceptions about the dance. Fortunately, times have changed and with it the image of belly dance.

After another performance of Oriental Fantasy, in Brussels, in October of 2003, a man of Greek nationality told me that he had watched belly dancing since he was a child but thathe had never seen a man perform it. He thought that in order for a man to be able to do whatIdid that night,he mustbe completely free ofall taboos. Thatmade me realize, looking back on my past, that life prepared and freed me from all inhibitions so that I am able to do what I do.

I was introduced to belly dancing by Magana Baptiste, wife of the great spiritual guru, WaltBaptiste.Bothofthembecamemyspiritualteachersandmyinspiration, providingme with high moral values and spiritual guidance. It was a performance by Magana, doing a cane dance or raks el assaya, that revealed the essence of dancing to me.

After years in the world of professional ballet, being surrounded by perfect bodies with amazing technical abilities, it would actually be a woman over fifty who showed me what dance was really about. When Magana, a mother of three, performed at that studio show, I saw such grace, such beautiful energy and light coming from her eyes as she danced, that I was inspired to become an oriental dancer myself. It would be through her encouragement that I began lessons at her studio and in time followed more lessons with numerous other teachers.

It was her husband, Gurudev Walter Paul Baptiste, who brought spiritual light into my life. Meeting him was a turning point in my life. Until then I had followed an ardent spiritual quest, but it was Walt Baptiste who provided me with a method of spiritual discipline basedonpracticalexperienceandnotonblind belief –aphilosophybasedon knowingand

noton speculating.

Thisis thestoryofmylife sincetheearliestmemories ofmychildhood.EverythingthatI

tell is true, although some passages may seem fantastic. I tell all, from the darkest passages tothemostsublimemoments:theexcitementofdiscoveringdanceatanearlyage;my dangerousaffairwithdrugs;theweirdandsometimesevenmacabrelifewithmyfamily;the wonderfulwaycircumstancesguidedmetoclassicalballetandencounteringbellydancing – which lead me to explore the complexity of Arab culture and the Muslim world.

My wife Beata tellsme she findsitamazing that Iwrote thisbook under the circumstanc- es we have at our dance academy. I am not the typical author writing in a private cabana, finishing a book within six months. I have written this book in the midst of chaos, little ballet children screaming, telephones ringing, dogs barking and dance students asking all sorts of questions. It has taken me over a decade to complete.

My experiences range from the normal to the outrageous. I share my highs and lows, my blissfulspiritualawakening,darkdepressionsandthe hardshipsofalateattempttobecome a classical ballet dancer.

I was encouraged by Belyssa, an oriental dancer from Australia, to write this book, and startedin1998torecallmyexperienceoflifeandofdance.Isincerelyhopetoentertain

you with my story and perhaps bring some insight into classical ballet and oriental dance at the same moment.

Chapter1

Childhood

They say it is the early impressions that set the pace for life. My childhood, itsparadisicalsurroundingsandmostunusualfamilyscenario,providedmewiththedrama, beauty, intensity and flamboyance I needed to express a wide range of emotions and char- acters I would later portray as a dancer on the stage.

I was born at home, delivered on my parent’s bed, weighing 6.5 kilos, on September 25th, 1956 in Cartagena, on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, in South America. I was baptized Catholic with the name Horacio del Cristo Federico Cifuentes Caballero.

Once,asateenager,whenIfeltthespiritofJesusstronglyinsideme,Iaskedmymother

whyshenamedme“delCristo”.Shesaiditwasduetoherdeepreligious devotion.

I do not know which of my mother’s thirteen pregnancies was mine. Of the five siblings who survived only one brother was younger. But by the time I arrived, there was no longer anycauseforexcitement.Mymother,ElidadelSocorroCaballerodeCifuentes,hadretained a beautiful figure even through her middle age, which was during my teens. She told me stories of stopping traffic when she was a girl. Her trick, she claimed, was achieved by tyingathinropearoundherwaistunderherdress,thusaccomplishingthehourglassfigure. TheCaballerosclanhadbeenanotoriousfamilyintheearlydaysofCartagena,when everyone stillkneweveryone.Thewomeninthefamilywere knownfortheirstrikingbeau- ty and the men for their frequent drinking bouts, fist fights and eccentricities. Probably the most notorious of the men was Felipe, my mother’s great uncle, who refused to be photographed. Mind you, these were the days when taking a family photo was a big to-do. Everyone would wear their finest clothes and gather on a Sunday to organize the event. Thefamily wouldlineupaccordingtoageandrankwiththeoldestin thecenter,VicenteCabal- lero, well into his eighties. As the photographer disappeared under his black cloth he re-questedeveryonetofreeze.Felipewouldturnhisbackatthelastsecond.Thiswenton

timeaftertimeuntilgreatgrandfatherVicenteforcedhimtoface thecameraatgunpoint!

Vicente Caballerowas anextremely elegant man, always beautifully dressed and perfectly groomed. Tall, handsome and in command, he had deep blue eyes and silver, curly hair. A fine artist, he created the frescos on the ceiling of the Teatro Heredia, the finest theatre in town – built like a small opera house in colonial style. He also constructed some of the floats that paraded for the Carnival of the 11th of November, celebrating emancipation of the slaves. Every year the parade showcased a beauty queen on a float. The whole event culminated with the selection of Miss Colombia.

My mother had white skin and thick black hair with a stripe of silver coming from the center of her head towards the back, like a chinchilla. She had round hips, a proud posture

and graceful manner. She had retained a natural pride that was typical of the Caballeros. They felt that they were really special in Cartagena. But by the time I arrived, that family honor was but a shadow of the past.

My family moved constantly and my earliest memories are that of an unstable home where we never completely unpacked. My father, Tomas Federico Cifuentes, a Captain in the Colombian Navy, was born in Buenaventura, in southwest Colombia, on the Pacific Coast, near Ecuador. He was tall, of dark skin, broad shoulders and pronounced features. His military training was reflected in his manner. He was tough, diligent and assertive.

He was the first mulatto (mixed-race African and European) to ever graduate from the Naval Academy in Cartagena, which was cause for controversy. His brilliant mind was threatening to higher-ranking officers. In fact, he was known as the most intelligent person to ever pass through the Naval Academy. But the racist society in Cartagena couldn’t get past his skin color. Yet, he became Colombia’s most sought after authority on naval engi- neering and was often sent abroad to build ships in foreign shipyards.

FatherwasstationedmostlyinBogotá,whilemotherwasattachedtoherrelativesandthe addictive Caribbean flavor of Cartagena – its gentle pace and relaxing atmosphere. She was never happy living in Bogotá, the nation’s capital, with its faster pace, cooler temperatures and even cooler temperaments. She found the polite and proper slang of the Bogotanos intolerably hypocritical. However, we never stayed in either city for longer than one year, which made it difficult for me to keep friendships.

MyfatherplannedforustoliveasettledlifeinBogotá.Heboughtlandinoneofthebet- ter sections of town, on a hill, with a beautiful view, and he had plans for a magnificent villa. But these never went past being grand ideas and wishful thinking. My mother’s an- swer was always, “we’ll see.”

No matter what mistakes my parents may have made while raising their children, thanks to my mother, I am the dancer that I am today. It was through her support that I was able to attend dance schools and have the freedom of artistic expression.

I clearly remember my father’s volatile temper and the aggressive way in which he resolved matters. Once I purchased a pair of fashionable sandals, only for them to detach fromtheir sole the following day. My father accompanied me tothe shoe store toregistera complaint. As the salesman refused to take them back, my father simply took one of the sandals and slapped the man’s face with it as he ordered him about with military commands. The pair of sandals were promptly replaced and we left the store without further comment.

Among my relatives, there was no such thing as a reasonable discussion. Problems were solved by yelling and throwing things about. Usually, whoever screamed last and loudest wasthewinner.Then,onewasinsultedanddidn’ttalktotheotherforawhile.Things

calmeddownintimeandbythenextfamilygathering,everythingwasallrightagain.

Mymotherwasdisorganized.Thedrawernexttoherbedwas theproof.Papers,buttons,needles,photos,thisandthatwere all crammed together without any order.

Thehouseholdwasattendedtobyatleastthreemaids.They cleaned, cooked, washed and did the shopping.

I remember one of them distinctively. She was a Native American girl from the outskirts of Bogotá, with the typical physique of the people from that region – short, of chocolate skin, straight black hair and a thick torso. Alma was missing several teeth and had a vulgar way of laughing. She gave me my very first French kiss, tongue and all, before I even made it to kindergarten. Whata shock I had when I realized that kisses are actually wet!

When we lived in Cartagena, usually the maids came from a townlocatedabouttwohoursawaycalledPalenque.The people

from Palenque had unusual customs. The women came to Cartagena early in the morning by bus and carried a huge palangana1 on their heads filled with exotic fruits. They walked elegantly, balancing the heavy load as they shouted the names of the fruits. The men did practically nothing but play dominos and smoke marijuana all day as they waited for their women to return. It was said that the women did not want the men to do too much during the day so that they would have plenty of strength to fulfill their sexual duties at night. The palenqueros also had a particular concept about life and death. When someone was born, theentireneighborhoodwouldgatheraroundthebabyandmournforit,cry,andfeel sorry forallthetroublesandpainthatthenewcomerwouldhavetoendure.Whensomeone died they threw a big party to play music, dance and celebrate the freedom of the soul.

As we moved back and forth between cities, in Cartagena I sometimes ended up staying withmyauntOlga orwithmygrandmaOctaviana,or‘Tata’,asweaffectionatelycalledher. Tata was very fat, wore her hair pulled back in a bun, and complained of varicose veins as she walked with difficulty, dragging her feet on the floor. She was actually my grandmother’s sister. She adopted my mother, my aunt Olga and five brothers due to my grandmother’s early death. Tata never married. Apparently she remained a virgin until her death. She was a tyrant to everyone around her except me.

Ifoundcomfortinhersoftlap.Shelovedme andhercaressesaffordedasense ofsecurity. I knew I could always count on her to provide me with the feeling of protection that I needed at that early age – physical contact that I had lost from my mother much too early.

Sometimesmy father wasorderedtoworkabroad.Mother went along,leaving us behind.

SomeofusstayedwithOlga,somewithTataorwithotherrelatives.Worstofallwasthat

1palangana:Aluminumcontainer filledwithtropicalfruitscarriedontopofthe headbyblackwomen.These graceful and strong women sell their fruits around the neighborhoods of Cartagena where they yell the names of the fruits out loud.

she never told me beforehand that shewas leaving.Afraid of a scene, she would just disappear. I found out by just realizing that she was gone – sometimes for months at a time.

I was always happy whencircumstances brought me to live with Tata. She was the owner and director of a girl’s school where she also lived. The Colegio Octaviana Vives. The villa wasyellow,and hadalarge staircase leadingup toasquareporch withfourconcrete pillars. On each side of the mansion were two majestic trees known as Kalso kapok trees. We just referred to them as cotton trees because each February they released little white seedlings, which floated throughout the neighborhood. They were the two largest trees in Cartagena.

The villa’s front door was solid wood, huge and divided in the center. A spacious hall with black and white, checkered, floor tiles served as foyer. It was an old mansion in a distinctive colonial style, built at the beginning of the 1900´s, now a girl’s school. The furniture was full of round lines. Every hour the grandfather clock stroked it’s deep gong. The backyard went all the way to the end of the block with various tropical fruit trees, occasionally used by iguanas and chameleons for their nests. Trees of mango, níspero, guayaba and mamón graced the yard. At least one of them was always in season, giving us plenty of fruit. In the center of the yard there was an abandoned fountain.

Some of Tata’s students on internship slept in quarters located towards the back of the villa. Others returned home in the afternoon after school. A driver collected them and delivered them daily. Tata, the driver and I went for a ride each afternoon to bring the girls home. At the end of the drive, I was rewarded with shaved ice to refresh us in the heat.The women and the trees provided a secure environment for me and I felt well as long as I was by Tata's side. My life seemed comforted by the abundant feminine presence. Between Tata’s school and various dance academies I attended throughout my life, many women have surrounded me ever since my childhood.

Although my family was never devout with regard to religion, we were encouraged to go toSundayservices.OurchurchwascalledIglesiadelaCandelaria,locatedjusttwohundred metersfromTata’sschool.Thechurchseemedmajestic,intimidatingandsomewhatmysterious to me. It appeared to be the highest authority governing our lives, dictating the moral values by which we lived, and allowing no room for dissent. Should anyone refuse its laws, he or she would end up in hell.

Upon entering the church one dipped his fingers in holy water and made a cross naming the father, the son and the Holy Ghost. Never mind that I didn’t know who these three entities were, but as in many other aspects of my childhood life, I had no right to ask. If I did, I was simply told, “because that is the way it is.” Subject closed. No discussion. Besides,thesubjectofreligionwastabooandconnectedwithsomuchfear,thatnoonedared ask anything about it.

TheIglesiadelaCandelariawasindeedabeautifulplace.FilledwithstatuesofMadonnas, saintsand all those importantimagesthat would, ifwe prayed tothem, supposedly solve all ofourproblems.Ofcoursewewerepermittedtolightacandleforthem,whichwould

certainlysecureaplaceinheavenafterwedied –ifwepaid.

If I did something wrong, told a lie or kicked my sister, I could confess my sins to the priest who would grant me a certain number of “Hale Marys” or “Our Father’s.” I would kneel ata bench, fulfill my task and then the nextSunday Ireceivedcommunion, apparentlywithGod,whichmeantIwasawardedaround,white,flavorlesscookie.Theneverything was all right again.

On Monday I went back to committing more sins and by the weekend I could repeat the process from the start.

Fora time, indeeda longtime, Itruly believedeverything thatwasimprintedon my mind by this mighty institution. However, out of the corner of my eye, during services, I would observe that there were others who would observe others instead of immersing themselves in the depths of religious devotion. Those were the first doubts I ever had about the Catholic system.

If I was to sincerely repent for my sins, why was I repeating these prayers like a parrot without emphasis on their true meaning? Moreover, it seemed like every other member of the church was doing the same. Not only did they follow the priest’scommand with robot-like precision, they also approached the service as a social gathering, using it as an opportunity to be seen in public and to be accepted as a good member of the community and a God-fearing Christian.

As time went on these questions came more and more to drift through my mind. Itwould be much later, when as a teenager, that I truly dared to challenge the credo that had been instilled in my consciousness. It was only then that I acknowledged my own criteria about what I felt was God, and my relationship with Him.

But I believed blindly, and my belief was so sincere that as I reached age ten, I went to church every day and saw myself becoming a priest as an adult.

My carefree life changed as soon as I had to attend school. My earliest memories are of conflicts with other boys. I shared neither their interest nor their taste in games of sport. I did not want to fight or play rough; by doing so I felt out of place.

My fate changed even more so when circumstances brought me to live with my aunt Olga.

Forreasonsunknown,IalternatedlivingbetweenOlgaandTata.Itwaslikebouncingbetween heaven and hell. Olga, unlike my mother, was not blessed with such striking beauty. She had rather pronounced features, round shoulders, no waistline and a thick torso. She had four daughters, one son, and a husband, Luis Fragoso, or “Lucho” as everyone called him – who was an ogre. Lucho was thin, had a mustache and spoke in low tones. He was the director of the school I attended, called Colegio de la Esperanza, and at dinner he would tell Olga and everyone else everything that happened that day at school. I sat quietly as everyone heard him describe what a difficult time I was having with the other children; that they terrorized me and that I was not man enough to fight back. He was the first person to treat me as a disaster case – to describe me as effeminate.

At first I did not even know what that meant, but judging by the tone of voice that was beingusedtodescribetheword,Iimaginedthatitwassomethingbad.Iwasunhappyliving with Olga and Lucho. He tried to toughen me up, make a man out of me. He talked to me with a militant voice. If I complained about being beaten up by other kidsat school, he just ordered me to “defend yourself like a real man should.”

I became somewhat neurotic and paranoid. Soon cousins and relatives had an image of me that would torment and haunt me for the rest of my childhood. I was afraid to playwith other children.

On Sundays there was always a big family affair at Tata's. She cooked a huge meal for everyone including one or two chickens from our own backyard, which we all chased before one of the adult men killed it in the kitchen – usually by twisting its neck. The family gatherings were lively and attended by many relatives. The menu was always the same – sancocho: a hearty soup containing chicken, beef, vegetables, with coconut rice and fried plantains on the side.

Often my mother was not present, she was traveling somewhere, accompanying my father.It seemedlikeshewasgladtobeabletoshakeoffherchildrenoneither Olga orTata. Many years later, when I visited Cartagena with my wife, Beata, I learned by accident that my mother left me to the care of my cousin Vicenta Caballero for seven months when I was only two months old. When I heard Vicenta casually tell me the story, I felt a knot in my stomach, as if somehow I already knew. Is it possible to have a memory of such anearly age? Certainly there must be some trauma deeply rooted in my subconscious to make mereactsoathearingVicentadescribehowmuchIcriedandhowshehadcaredformeby placing a radio at my side. “Music was the only way to quiet you down.”

I recalled my fear and early memories of being frequently left behind. Even ifmy mother needed to run errands downtown she would sneak away without me seeing her, to avoid a scene. When I became aware of her absence, I was comforted by one of the maids.

As my mother heard Vicenta tell me the story, and she felt my eyes search for hers, she looked the other way, embarrassed. Her guilt was obvious.

It was later in life, after we moved overseas, that I realized that as a child I actually livedin a paradise. The homes in our neighborhood resembled those in the deep south of the United States. The ones on our street, Calle Real, all had a large staircase leading to their entrance and huge backyards with tropical fruit trees. I spent lazy hourssitting on the front porch merely waiting fora car to drive by. Back then, that was a real event, a stark contrast to the traffic jams of today. Sometimes, when mother took me with her shopping down- town, we would come back home in a coach driven by a horse!

WhenIwasoldenough,Itookthebustoschoolmyself.Incidentally,thosebusesarestill painted in every color of the rainbow and usually the driver places a small statue of a saint oraMadonnaonthedashboardforprotection. InCartagenathere arenospecificstopsfor buses. One can just wave and the bus will stop anywhere.

Once, very early in the morning, while going to school, I sat daydreaming in the frontseat as the driver saw a rather attractive woman come from the far end of a side street. He stoppedthebusandwaitedforher.Thewoman,avoluptuousLatinbeautywearingatight dressandhighheels,did notmaketheslightestefforttohurry,althoughshe wasmorethan one hundred meters away. She took her sweet timeand walked, slowly, swinging her round hips for several minutes until she reached the bus. The other passengers, the bus driver,and myself, just waited and admired the young woman. Using her great feminine power,she seemed to hypnotize everyone by simply not rushing. When she finally arrived, in a cloud of fine perfume, she squeezed her legs together to be able to make it up on to the bus. She entered and sat down with sublime composure, knowing that she was the objectof each man’s admiration.

Shewasdefinitely worththe waitI thought.

ThereissomethingextremelydignifiedaboutwomeninColombia,alandwherebeautyis considered the highest virtue in a woman and where any lady, poor or rich, always makesan effort to beautify herself and the environment around her.

Cartagena, known as the “Pearl of the Caribbean,” is hot twelve months of the year. The downtown or old city is surrounded by very thick, stone walls (some, 10 meters thick), which the Spaniards built to protect the city from pirates and buccaneers. However, thereis softness in everything within those walls, of that city. The airs, the fragrance, the flavorof the countless fruits, the warm, bath-like ocean water, and of course the music.

Coastal people are extremely musical and weekend parties are just as routine as Sunday church. Everyone danced, and especially around the time of carnival, huge tents were setup featuring the famousbig bandsfromneighboring countriesofVenezuelaand Panama. I loved watching adults dance and I frequently stood outside the parties observing through the windows how couples would sway to the rhythms of merengues and guarachas.

Often ourmaidsdanced witha broomifthe newesthitsong wasplayed on the radio. My parents, excellent dancersboth, were showstoppers and always inspired the rest of the party to make a circle around them. I felt proud watching them. My father, always strong and handsome, lead smoothly, and my mother, who followed him so perfectly, swayed her hips gracefully.

Of my numerous uncles, Fernán was the most impressive. He was always impeccably dressed. In his constant battle against perspiration, he changed outfits up to three times a day. His image was and still is an inspiration for me today – a picture of elegance and good manners. His generation included a circle of men in Cartagena who would not be caught deadwithsomuchasaspeckofdirtontheirclothing.Manyofthemworeonlywhitefrom head to toe, interrupted by a black band on their Panama hat and a black belt. Elegancewas a must and was revered as a virtue.

Another uncle who left an imprint in my subconscious was Horacio Caballero, who also happened to be my godfather. A very wealthy doctor, uncle Horacio was the subject of much gossip due to an illegitimate son whom he claimed was his godson, until the young boy grew to be the spitting image of him, with his exact eyes, hair, posture and mannerisms. Everyone in town laughed about that.

ButuncleHoracio’strademarkwashisstinginess.Consideringthathewasactuallyfilthy rich,hewasverytightwithmoneyandlivedverymodestly.Whenhediedtherewereloads and loads of cash found under his mattress and hidden inside the walls, partly rotten from the humidity and tropical heat.

What I learned from uncle Horacio was that being rich means more than having money. What is the point of having a lot if your attitude towards life is small minded?

As a consequence of my father’s travels, I had the privilege of receiving exotic presents whenhereturned,eitherfromJapan,theUSAorwhereverhisjobtookhim.Afteropening mypresentswesharedlittleornocontact.Hiswasapowerful,patriarchalimage,whichleft a huge gap between us. I was threatened by his exaggerated masculinity, something that, according to my uncle Lucho, I was supposed to have severely lacked.

The bus driver at Tata's was usually kind to me and I was not sure what to think abouthis asking me to accompany him into a hidden part of the yard at dusk. Making sure thatwe were unseen he dropped his pants and demanded caresses. I was four years old at the time. Threatening reprisal, he stressed that no one should know about it. I was petrified.My lips were sealed. The rendezvous seemed mysterious and confusing. I was afraid of a terrible reprimand if our secret ever came out.

Yet this man seemed to have a certain power over me. He would tell me fascinating stories about his relationships with women; how he would take his girlfriends to the walls that surrounded the old city and rub his genitals against theirs.

“Womenaredifferentthanweare”hesaid.

“Theyhaveembarrassingmoments.Sometimesthey bleed.”

Whenhetookmetothemovies,wesatwayattheveryfrontwheretheseatsweremostly empty. There he forced me to touch his genitals. It was all such a bewildering experience.

One night, he managed to enter my bedroom after my nanny had already put me to bed. He charmed his way into my bed and attempted penetration, which he fortunately did not pursue when I complained of it being uncomfortable and painful.

The next day I broke the silence. I told my nanny about the unpleasant encounters with the man and there was a scene. Tata, my nanny, the driver, some other adults, and myself had asortofconference.Iwasabsolutelyterrified and held onto mynanny’sleg hidingmy faceagainstherlap.Tataquestionedmewithasterntoneofvoice,“Didhetouchyou?Did he? Tell the truth!”

“Yes,hedid,”Iansweredinalowvoice,withoutremovingmyfacefromnanny’slap,

whilefeelinglikeatraitor.

I was taken away from the room and never knew what consequences the man suffered from the events. I never saw him again. My mother, who was away on a trip, never mentioned the matter when she returned.

This horrid passage in my early life was something I hid inside the deepest corner of my subconscious for decades. It was not until I was married that I confided with my wifeabout what occurred. It did leave a deep scar in my heart. I am still working on healing my heart.

Therewasanothereventinmyformativeyearsthatcausedmegreatsadness.Onedaymy

motheraskedmetocollectmytoysfromthestreetbecause,“someonecouldstealthem

from me.” When she saw the puzzled expression on my face she proceeded to explain that there were, “badpeople who stole things andcouldhurt others.” I was absolutely devastated and felt as if a black cloud suddenly darkened my entire world. That was truly the day when I lost my trust.

Communication between my father and I was practically non-existent, nevertheless, his image of discipline was deeply rooted in my subconscious. He rose early, was always clean, well groomed, hardworking and consistent, qualities which I found in myself later in life during ballet training.