7,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In

Horos, Thea Potter explores the complex relationship between classical philosophy and the ‘

horos’, a stone that Athenians erected to mark the boundaries of their marketplace, their gravestones, their roads and their private property. Potter weaves this history into a meditation on the ancient philosophical concept of

horos, the foundational project of determination and definition, arguing that it is central to the development of classical philosophy and the marketplace.

Horos challenges many significant interpretations of ancient thought. With nuance and insight, Potter combines the works of Aristotle, Plato, Homer and archaic Greek inscriptions with the twentieth-century continental philosophy of Heidegger, Derrida and Walter Benjamin. The result is a powerful study of the theme of boundaries in classical Athenian society as evidenced by boundary stones, law and exchange, ontology, insurgency and occupation.

The innovative book will be of interest to scholars in the fields of ancient Greek social history, philosophy, and literature, as well as to the general reader who is curious to know more about classical life and philosophy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

HOROS

Horos

Ancient Boundaries and the Ecology of Stone

Thea Potter

https://www.openbookpublishers.com

© 2022 Thea Potter

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text for non-commercial purposes providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Thea Potter, Horos: Ancient Boundaries and the Ecology of Stone. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2022, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0266

Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. This information is provided in the captions and in the list of illustrations.

Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.

In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0266#copyright. Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web

Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0266#resources

ISBN Paperback: 9781800642669

ISBN Hardback: 9781800642676

ISBN Digital (PDF): 9781800642683

ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 9781800642690

ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 9781800642706

ISBN XML: 9781800642713

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0266

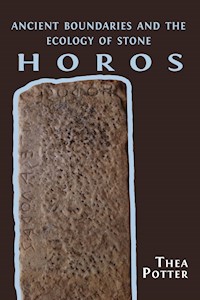

Cover image: ΗΟΡΟΣΕΙΜΙΤΕΣΑΓΟΡΑΣ, The Athenian Agora Museum [I 5510]. Reproduced with permission from the Hellenic Republic Ministry of Culture, Education and Religious Affairs, Directorate General of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens, Department of Prehistoric and Classical Sites, Monuments, Archaeological Research and Museums. Cover design by Anna Gatti.

Although there may be no outside that we can know, there is a boundary.

— Katherine Hayles

Να έχουμε μια πετρούλα. — PZ

Contents

Abbreviations

ix

List of Illustrations

xi

Acknowledgements

xiii

Prologue

xv

Introduction

xix

1.

A New Ancient Petrography

2

2.

Does the Letter Matter?

46

3.

Breaking the Law

80

4.

Terminological Horizons

118

5.

The Presence of the Lithic

154

6.

Geophilia Entombed or the Boundary of a Woman’s Mind

196

7.

Solon’s Petromorphic Biopolitics

240

8.

I Am the Boundary of the Market

278

Bibliography

286

Abbreviations

Ag.

Agamemnon

Alk.

Alkestis

And.

Andocides

Ant.

Antigone

Ap.

Apology

Ar.

Aristotle

Arist.

Aristophanes

Ath.

Atheneion Politiea

Cat.

Categoriae

de An.

de Anima

Cael.

de Caelo

Def.

Definitions

Int.

De Interpretatione

Deut.

Deuteronomy

Diog.

Diogenes Laertius

DK

Diels-Kranz

EN

Ethica Nichomachea

FDA

Federal Drug Authority

Gen.

Genesis

Grg.

Gorgias

Harp.

Harpocration

Hdt.

Herodotus

Hes.

Hesychius

Hom.

Homer

Hos.

Hosiah

Il.

Iliad

IG.

Inscriptiones Graecae

Job.

Job

KJ

King James Bible

LS

Liddell and Scott

Met.

Metaphysics

Meteor.

Meteorologica

Mor.

Moralia

MP

Member of Parliament

Myst.

On the Mysteries

Od.

Odyssey

OED

The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

Phd.

Phaedo

Pl.

Plato

Plut.

Plutarch

Prov.

Proverbs

Pol.

Politica

NIV

New International Version

Rep.

Republic

Rev.

Revelation

Rhet.

Rhetoric

Sol.

Solon

Suid.

Suida

TGL

Thesaurus Graecae Linguae

Top.

Topics

Trach.

Trachiniae

Vit. Phil.

Lives of the Philosophers

WHO

World Health Organisation

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1.

ΗΟΡΟΣΕΙΜΙΤΕΣΑΓΟΡΑΣ ‘I am the horos of the agora’, IG I³ 1087 [I 5510]. Photograph by M. Goutsourela, 2013. Rights belong to The Athenian Agora Museum © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.R.E.D.)

1

Fig. 2.

ΑΧΡΙΤΕ[Σ] ΗΟΔΟΤΕΣΔΕΤΟΑΣΤΥΤΕΙΔΕΝΕΝΕΜΕΤΑΙ ‘The city extends up until the edge of this road here,’ IG I³ 1111. Photograph by T. Potter, 2021. Rights belong to the Epigraphic Museum, Athens © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.R.E.D.).

45

Fig. 3.

ΗΟΡΟΣΤΕΣΟΔΟΤΕΣΕΛΕΥΣΙΝΑΔΕ ‘horos of the road to Eleusina’ (end of the 5th c BC). Originally inscribed with HOROS TES ODO TES IERAS (520 BC). IG I³ 1096 [I 127] Photograph by M. Goutsourela, 2013. Discovered in the Eridanos river bed. Rights belong to the Kerameikos Museum, Athens. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.R.E.D.).

79

Fig. 4.

[Δ]ΕΥΡΕΠΕΔΙΕΟΝΤΡΙΤΤΥΣΤΕΛΕΥΤΑΙΘΡΙΑΣΙΟΝΔΕΑΡΧΕΤΑΙΤΡΙΤΤΥΣ ‘Here ends the trittys Pedieis, while the trittys Thria begins’ IG I³ 1128. Photograph by T. Potter, 2021. Rights belong to the Epigraphic Museum, Athens © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.R.E.D.).

117

Fig. 5.

OΡΟΣ ΛΕΤΟΣ ‘[h]oros of Leto’ Photograph courtesy of Paulos Karvonis, The Island of Delos, Ephorate of Antiquities of Cyclades, © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.R.E.D.)

153

Fig. 6.

Gravestones. Photograph by M. Goutsourela, 2013. Rights belong to the Kerameikos Museum, Athens. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.R.E.D.).

195

Fig. 6a.

ΗΟΡΟΣΜΝΗΜΑΤΟΣ, in Lalonde (1991) [I 7462]

195

Fig. 6b.

ΗΟΡΟΣΣΗΜΑΤΟΣ, in Lalonde (1991) [I 2528].

195

Fig. 7.

ΟΡΟΣΚΕΡΑΜΕΙΚΟΥ ‘Οros of the Kerameikos’ (4th c BC). Found outside the archaeological site in the area between Hippias Kolonos and Plato’s Academy. [I 322] Photograph by M. Goutsourela, 2013. Rights belong to the Kerameikos Museum, Athens. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.R.E.D.).

239

Fig. 8.

ΗΟΡΟΣΕΙΜΙΤΕΣΑΓΟΡΑΣ [retrograde] ‘I am the horos of the agora.’ Horos stone discovered in situ in the northeast corner of the Ancient Athenian Agora, by the Tholos. IG I³ 1088 [I 7039] Photgraph by M. Goutsourela, 2013. Rights belong to The Athenian Agora Museum © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.R.E.D.)

277

Acknowledgements

Thanks to James K.O. Chong Gossard and John Rundell who supported the nomadic beginnings of this work during my doctoral studies at the University of Melbourne. Many thanks to Roger Scott and Penelope Buckley for their unwavering generosity in keeping me housed and fed at many crucial moments. Thanks also to Louis Ruprecht Jr. for feeding my enthusiasm and keeping it buoyant. A thousand thanks and more to Despoina Koi for looking after the boys and giving me the boon of uninterrupted time. Thanks too to the boys for interrupting me with such boisterous jollity. Maria Krystalidou and Elina Niarchou, ευχαριστώπουλάκιαμου, σαςαγαπώ. The entire project would be inconceivable without my father’s unswerving love and interest in things of the mind and things of the earth. I have never seen him refuse to engage in an argument no matter how unconventional, I have never seen him too tired to read another book or too busy to answer my questions about the composition of rocks or the identification of trees. I dedicate this book to him, because I know he will get more pleasure out of it than anyone, if only because it was his daughter who wrote it. Finally, many thanks to the whole team at Open Book Publishers!

The research for this book was conducted thanks to the Jessie Webb scholarship (University of Melbourne), during my stay at the British School at Athens, the Irish Institute of Hellenic Studies at Athens, and using the wonderful resources in the libraries of the American School of Classical Studies and French School at Athens. Photographic images from Archaeological sites in Athens are by myself and M. Goutzourela and are presented here by copyright permission from the Kerameikos Museum, Athenian Agora Museum and Epigraphic Museum © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.R.E.D.).

All translations are by the author, unless otherwise indicated.

Prologue

When Edward Said visited Lebanon, he picked up and threw a stone across the border to Israel. For this act he was barred from attending certain institutions. During the French Revolution stones, frequently the humble cobble, were thrown against the troops and added to the piles of refuse forming the barricades. Again, in England, during the suffragette movement, women wrapped stones in paper, tied a string to and threw them at public offices, drawing the string to retrieve them and throw them again. During the Al-Aqsa Intifada in Palestine it was an iconic image of a young boy throwing stones, later killed by the Israeli army, that attracted the attention of the international media. In a simple protest in Athens against education cuts in 2008, a youth throwing stones was killed by police, causing a general revolt. In Egypt during the latest uprising, stones littered the streets even as the military was sending in tanks.

Must we be satisfied in agreeing with Blanqui that the stone is the principal article in urban battles because it is most ready to hand?1 Or has the stone gathered this reputation for insurgency on account of history’s momentum, resurfacing every time because of its presence in a former revolt? As Lacan said, perhaps the stone has become an objet petit a for the revolutionaries.2

But what if the symbolism of the stone is not limited to these recent acts of historical insurrection? What if the stone itself already marks our responsibility to struggle for what we know to be right? What if the stone actually stands as a testament to what we cannot see in the immediate world around us but presents a most substantial challenge to the status quo exactly because something has been missed, overlooked, or simply lost?

This work undertakes to bring before our gaze an intrinsic relation between stone and human, in a study that is inversely archaeological. It traces the earlier possibilities of the stone’s task in archaic Greece and describes its subsequent modifications, losses, appropriations and occupations during the rise of the historical, political and in uteroeconomic era of the classical world. Oddly enough, the resulting arc does not begin in corybantic times of cultic religious practice where the stone is presumed to be a fetish or animistic token, to find its epistemological culmination in materialism and utilitarianism. In fact, it would appear that, in relation to this base matter, we have been moving in the opposite direction. What began as simple (though not base) stone has gradually become fraught with all sorts of religious, political and economic investments in every aspect of life, that is, except insurrection. For although we employ stones, crushing them and piling them up in the construction of buildings, roads and walls, here the stone, in content and form, is in every way subordinated to the increasingly hostile environment we are building around us, blocking out strangers, ensuring swifter means of progress and limiting in every possible way the direct confrontation and interaction with others, human or otherwise.

We throw stones to bring us back to the matter at hand. As the marker of our graves the stone should be at once a material and metaphysical remainder of the fact that we are all strangers to life, regardless of nations, states and the self-interests of markets, corporations, security and defense. The stone stands as a marker of our ongoing and necessary relation with the more than human world. Although we dismiss stone as inanimate, it is the origin of animation, whether it disintegrates into its more readily available fertile components or erodes into the various formations upon which the diverse play of life is acted out.

It is in this light that the insurrectionary stone-throw should be understood. For it is an act directed against the hubristic violence of the border and the barrier, the wall and property. The stone-throw gestures towards what is common by putting such boundaries into question and by transgressing boundaries with the most solid (though not immutable) material that inevitably takes our place and even substitutes for us. For the stone-throw yet retains the possibility of the dissolution of the militarised border, or the armed aggressor. It is a symbol of friendship winning out over hostility. All who wish it are welcome to join the insurrection. The problem every insurrection faces is, however, how long the people are prepared to fight guns with stones before the injustices they have suffered compel them either to turn inward in despair and accept the terms of the victor or to embrace the same means of violence that are directed against them.

The rune-masters carved their runes in rock, wood or leather and then coloured them with magical ingredients, one of which was likely blood. In order to read the prophecies hidden within these objects the masters dispersed them upon the ground, and it was only those with the letter facing upward that provided the text for interpretation. This book could be said to follow a similar method. Since the text has (in the wake of deconstruction) proved itself exhausted, if not a mere ruin, this is an attempt to remain close to the material foundation of writing about writing. It is no coincidence, therefore, that the plinth upon which this text rests is literally a ruin. The earliest archaeological remains that will be considered here are mere traces of letters, found amongst the rubble, sometimes engraved in stone, other times in a text no less spoliated. They are literal remainders of an earlier, lapidary writing, whose name ‘Horos’ equally binds letter and stone: declarative letters whose stony annunciation would make a belligerent claim of precedence to any writing. Horos is the original material as well as the place-saver of Hermes’ own statue in the Athenian market place. Though ancient, Horos remains throughout the hermetic period and into today when only interpretations and not positions are considered to be safe ground for thought.

There is a lot of talk of boundaries and bonds in the following pages. It is not my intention to wield bolt-cutters or claim to have found a key to dissolve these boundaries and free us of these bonds but rather to trace a path that should foreclose any arrival, such that the question remains. Questioning must begin somewhere. This book discusses the site or place of the question as both a matter of boundaries and definitions, where any question also allows the definition of words and things to remain open to the possibility of asking further questions. Here the boundary of the question is present in the stone as our trace or mark, with or without letters, of the potential distinctions and divisions in the material. In light of this return to the elemental material of stones and of letters it is necessary to ask what has been lost from our relations with the world and one another. Perhaps in what has been lost there is a chance of rediscovering a ground from which to resist and destroy the forces that occupy and with increasing aggression seek to manipulate the archaic frontiers of life.

1Blanqui (2003).

2 Roudinesco (1997) 336.

Introduction

© 2022 Thea Potter, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0266.09

The market today resembles a Leviathan, a great beast growing in accordance with no law outside of the vain rapacity of its uncanny monstrosity, extending its boundaries beyond the nation-state, beyond government intervention, beyond ecologically safe limits and beyond our will to enter into it. It has become properly automatic, functioning for no purpose outside of itself, its masters simultaneously its slaves. And yet, this monstrous system originates with us. Have we lost control of this love child of unsatisfied desire and self-gratification? Are there no limits to its cancerous spread? Is there any way to assert our responsibility over and against the unlimited expansion of this voraciously consumptive automatism? Nobody can doubt the existence of material limits to economic developments, though there must be a huge discrepancy in the location, orientation, the matter and meaning attributed to such limits; otherwise there would not be such wide-ranging discussion concerning the mechanisms and alimentation required to keep the current system from collapse.

Here the basic argument will be that vital material limits both structure our relation in and with the world around us, comprising both humans and nonhumans, and call us back to an inclusive, inter-relational coexistence with all things in stark contrast to the reification of organic and inorganic natural resources required to maintain the unsustainable rate of technological advances in societies dominated by corporate, stakeholder capitalism (otherwise known as cartelism). To hold thus to the vitality of matter does not bracket out human subjectivity, its genesis and its boundaries; rather, it reinforces that the boundaries themselves separating the human being from everything else are not absolute, transcendental nor divinely given. But that does not mean that they are not substantial; they are, in fact, material. Because they are material, they are also subject to question. Therefore, as I will elaborate throughout this work, the project of Western human rationality is based upon a premise (that humans are ‘rational animals’ and distinct from other organic beings) that is epistemologically and ontologically secured by nothing but the very thing that the definition seeks to distinguish humans as separate from. This book is devoted to investigating this thing in the material origins of the philosophical and archaeological project of definition. The foundation that provides the definition distinguishing the human from the other inhabitants of the world, but also from the inorganic matter of the world is none other than ‘insensate,’ or ‘inanimate,’ matter itself.

Given that matter provides the substrate for all being, human or otherwise, why, it could be asked, the need to respond in like by advocating for the vitality of matter? The answer is that I agree wholeheartedly with Jane Bennett when she states that ‘the image of dead or thoroughly instrumentalized matter feeds human hubris and our earth-destroying fantasies of conquest and consumption.’1 In that light the project here is to trace a history of the vitality of matter and investigate how we have come to be psychologically, spiritually and linguistically disconnected from the world around us and the life inside us. This study reveals how the economically and politically dominant conceptualisations of matter, natural and otherwise, are contingent upon exclusions and exceptions that, reinvented within our language, could provide a deep kinship with the earth and open up the possibility of coming to terms with matter in a more involved, intra-active, symbiotic way.

How is matter vital? It is certainly vital to our survival, but it is vital in more ways than simply our dependence upon matter to provide us with warmth, food, and comfort. Matter is also vital to itself, and the relations of plants, fungi, animals, rocks, water, carbon dioxide, calcium, etc. all continue to interact regardless of human needs, intervention or even human existence, though no doubt these relations are increasingly modified and even hindered on account of human interventions (such as industrial farming depleting communities of biota in soil, the interactions between methane trapped under the ice with a heating atmosphere, or the affinity between asphalt and predatory birds). This then, might be the cause of the book, or what caused it to be written. The argument presented, however, requires these interrelations as an assumed foundation upon which all human and nonhuman activity plays out. It is the ground upon which we stand. But it is also this ground that poses the dilemma I attempt to confront or abide by: do boundaries exist in nature? Conversely, is this problem inscribed in the human assumption of such boundaries in defining nature as separate to humans? Does ‘nature’ take everything into account except the human, and does ‘matter’ likewise exclude whatever is organic or has a soul? Are such boundaries even sensible given the predisposition of the human to say that nothing matters or is meaningful beyond human volition to make it so? The question must be raised as to what actually is the nature of the boundary that claims to distinguish humans from everything else; is it natural or is it in us? We have been taught that the boundary is located within the human. For example, the presence of reason within the human mind is what distinguishes the human as possessing subjectivity. Beyond or outside of this subjective position, there is no way to prove the nonexistence of other subjectivities. At least, any attempt to do so always recoils into the precedence of human subjectivity as the principal determination. It is this problem, then, that this book presents as intrinsic, not to the nature of what it means to be human, but within nature as the possibility to determine, define and divide.

It is the reflexive task of philosophy to unravel the meaning of words and things, to use language to define the use of language itself. Ancient Greek philosophy began as a play on words, a kind of game that illustrated philologically the relations between words and things, their meanings and non-meanings, and evolved into the Aristotelian project of definition and determination. Such a project may have become speculative but its origins are deeply embedded in the bedrock of the archaic psyche. We could also turn this around and say that the archaic psyche was embedded deeply in bedrock. The coincidence between thought, language and rocks might not seem likely. However, it is exactly this essential and most substantial coincidence that I reveal both in the material traces of archaeology as well as the no less material remains of Aristotelian philosophy and Solonic law. In fact, it becomes increasingly apparent that it is impossible to think about anything in the absence of some kind of lithic term cementing our path along the boundaries of human and nonhuman conceptual, that is to say non-concrete, experience.

This study has to do exclusively with this lithic term. I approach these limits without any attempt to transcend them, transgress them or erase them , taking in solidarity an archaic example of a stone: this stone I call horos because this is what it calls itself. A boundary-stone found during the excavations of the ancient Athenian market-place enunciates itself and with an inscription takes upon itself the responsibility for providing limits. Retaining even into the Classical period the archaic spelling (when the letter eta represented the aspirant rather than the long vowel sound), this stone reads ΗΟΡΟΣΕΙΜΙΤΕΣΑΓΟΡΑΣ, ‘I am the boundary of the agora.’ The Classical Athenian agora,the market-place, was demarcated by a number of these stones, which prohibited patricides and other criminals from entering the market-place. But they also prevented the activity of the market from leaving that sacred site. These stones thus demarcated the limits within which the work of the market was to take place, there where Athenians went about the unhindered task of exchanging, producing and reproducing verbal and more than verbal goods.

So, the horos stones demarcated the space of the agora, and it is believed that the agora took its name from the activities that were first conducted there, a space for the shared rituals of speaking (agoreuein) and the further tasks of more than linguistic exchange, of buying and selling (agorazein). As Socrates’ presence there illustrates, the agora was a public space open to the redefinition of linguistic boundaries and questioning the value of words and other tangible and intangible goods. That questioning was based in and isolated within the same space as that committed to the exchange of goods, where measures and weights were brought into parallel with quantities of things, suggesting an (unheimlich) affinity between economics and philosophy. Both philosophy and exchange throw into question common values and, perhaps for that reason, were kept at a distance from domestic life, out of the household and its everyday activities, in a move that dissociated both tasks from their etymologically nested origins. There is a danger involved here, and the explanation of Marx might be well founded, although hypothetical, that exchange was first confined to the boundaries between tribes because of the risk of dissolving all communal bonds. The creation of a market-place within the confines of the ancient city may well be the first attack on the synergistic cohesion of the community.

Horos is a boundary-stone, a landmark, but it is also a term or definition, indicating a certain duration of time, a limit or boundary. It is also said to be a rule, a measure, an end or aim, the three terms of astrological measurement, notes of a musical scale, decree of a magistrate, and (apparently metaphorically) the boundary of a woman’s mind. On top of, or rather underneath, this greater plurality of meanings, it is also the stone that marks a grave—gravestone. As this material monad embodying a plurality of linguistic configurations suggests, there is a vitality to this boundary that cannot be reduced to demarcating a separation between hostile territories. The horosdefines and distinguishes, but that is precisely what the matter is with the word, and no matter how much we try to rub away the material connotations, its definition remains interminably solid, lithic, in fact. The horos cannot be read as choosing sides but does stand testament to our ability to distinguish between words and things, the human and the nonhuman. Nonetheless, when it comes to defining these things, us and itself, its own reflexivity confounds the attempt; the definition of horos cannot define the stone away out of presence, the stone is as vital to the horos as the word is to the definition of the boundary. It marks the differences that we read into the world, creating the distinction itself between the ‘natural’ and the human, while materialising the proof that this distinction is not in the least natural: or at least that what is natural in us, to read into stone something meaning more than base matter, creates the divide in nature and is exactly what determines us within and against the natural world while joining us to it inseparably.

The term ‘nature’ is conventionally proscriptive, describing all processes and beings other than the human and human creations. This book is structured around the distinction between the human and nature, between the human and nonhuman and describing the nonlinear history of this petrifyingly dualist construction. The irony is this: the presumption—that humanity alone raises the stone above its base materiality—is in fact the only basis for a theory of inanimate matter or a non-conscious cosmos. This division provides the framework for later economic developments based upon a non-synergistic or non-symbiotic relation with other beings, from bacteria, plants and animals to the gases that keep us alive and the geological formations that provide more than merely the substrate for life; today this is realised in the unbounded utilisation of the nonhuman world and the indubitably vain attempts of subjecting it to total human control. It is also the mystical origin of the project of Western scientific rationalism. This is the dilemma of human culture: it is based upon the reading of an unwritten division from (human) nature. The horos is a Greek concept, and its power is maintained within societies whose fundamental political and economic structures derive or in some significant way have been influenced by that specific heritage. That said, given that both the political form of democracy and the economic as a public structure of the unequal organisation of wealth are now exported worldwide, there is an expanding sense of importance in putting into question this unconscious rule of horos.

Foucault argued that there are rules—conceptual rules—common to different cultural practices and scientific disciplines, that work unconsciously to direct the many different fields toward their different goals as a ‘positive unconscious of knowledge.’2 I suggest that horos is one of these rules. However, unlike Foucault’s rules that seem to be period-based, the horos is an economic rule, a rule fundamental to an entire form of economics grounded upon the unequal distribution of land and goods and unlimited natural recourse use. But it does not need to be this way. The horos could just as easily be an ecological rule resisting and rebutting the unbounded exploitation of the nonhuman as well as of the human.

This book is called an ecology both because its author would wish that our interactions with the lithic were less invasive, less aggressive, less consumptive and more involved and also because it has to do with the definitions that we use in order to build the possibly spectral house of human knowledge, culture and society. The presence of boundaries, from the material remains of ancient boundary-stones to the determinations in quantum physics, saturates the shared life of humans. Boundaries are placed, maintained and transgressed in order to facilitate the material practices and social theories through which we divide the world into a plethora of categories, not the least being that of the ‘social’ and the ‘cultural, or ‘human’ and ‘nature.’ We require boundaries, in definitions or divisions, in order to make these categorical determinations. Ironically this also means that the boundaries must already exist as precedents to any subsequent determination. Does this mean they are predetermined? And if they are predetermined, is meaning already inscribed within them? The main question that this book seeks to raise is whether boundaries exist in nature, but not in order to contrast natural with social boundaries or in any way privilege human ethics. Instead the intention is to draw attention to the human edifice of language and culture, the behemoth of our civilising project that has managed again and again to do away with any notion of boundaries (natural or human), including those that might limit industrial farming, land use and hyper-development, the biopolitical use of humans and animals, the corporate abuse of biopower, and the use of just about everything else as biofuel, not to mention all those rocks and minerals blasted into nonexistence in the search for precious rare earths required in electronics necessary to track, modify and manipulate further what it means to be human.

And yet a limit is out there, threateningly immanent though no less withdrawn than that vital distinction separating being and nonbeing or creation from extinction. Here our lives are lifted into the geological scale as if our inability to recognise boundaries in nature or limits in our own nature is obfuscated by a predetermined fate as inevitable as the wearing away of rocks by wind and water. No single actor can be held responsible for the market, for drawing up its limits, or opening them up. And yet a limit exists, and this limit names itself, declares a name for itself, and a place of belonging: ‘I am the boundary of the market,’ reads the stone. But it is read by us, and it is therefore us, the actors, who enter into the market place who read and are responsible for defending the limits and for expanding them, as much as we are the ones who inscribe the stone, read the stone and cross the boundary. The peculiarity of the ancient Athenian market-place as an exclusive site of exchange, of objects and money but also of words, culminates as the setting of Socratic dialogue. The danger the Athenians attributed to such activities is given as the cause for the erection of the stones upon its boundaries, while the activities themselves draw us to raise further questions about the notion of boundaries as such and the questionable subjectivity of this self-enunciating stone.

Horos means ‘boundary,’ but it is also a stone placed to mark a boundary. In a way, though, I’m not so interested in spatial boundaries that divide or demarcate two spaces opening them up to possession and the rights of the owner, nor even the piece of land they foreclose. What I’m more interested in is the stone itself, both as matter and marker, and as obscuring the presence of a natural (human) marker. The intimacy of human culture with stone might be everywhere apparent, and yet studies into stone from a literary perspective are few. Two notable examples are the similarly titled John Sallis’s Stone and Jeffery Cohen’s Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. Both these works address the stone as something worth considering in its own right. Sallis takes up the stone in its sculpted form to investigate the sense of the sublime in stone, and in so doing he writes a philosophy of the cultural history and aesthetics of stone chiefly in art and architecture. Cohen is interested in the wide uses, practical but also literary, of stone during the Middle Ages in Europe. As the title suggests I would like to position my study in dialogue with Cohen’s epic work. My topic might precede his chronologically, but it certainly follows his thematically. Luckily for me, neither Cohen nor Sallis take up the particular example of the stone horos. So, I hope that this work on the horos will be a useful addition to this as yet small lapidary field. If nothing else it should raise the problem of the horos and its relevance in the field of ancient economics and political philosophy.

In the tradition of apophatic theology, I begin by introducing this book in the negative, by what it is not. It is not a historical study, nor a philological or philosophical study. This book takes place on the boundary between literary criticism, social theory, classical studies and archaeology. Based on interpretations of Ancient Greek texts about terms and definitions and archaeological remains of boundaries, it remains within the margins of Ancient Greek society, though the only reason I am interested in these margins is because of the play of their absence/presence today. So, my perspective on these ancient phenomena is undisguisedly modern, though I hope for all that it is also a little untimely too. In addressing the problem of meaning and matter, or the matter of meaning, I have taken a cue from Karen Barad, who manages to reconfigure quantum entanglements and physical-semiotic relations in a way that I believe strongly resembles the problem raised (or founded) in the horos. Jane Bennett, Carolyn Merchant and Val Plumwood also significantly figure as theorists who provide me with alternative bases upon which to think through human relations with ‘nature’ and the material world. Finally, Jacques Derrida remains as always on the margins of the text, if only because he, with Levinas’s assistance, framed a theory of hospitality that I believe to be essential when considering relations not only with humans in particular but also with the earth, mother of all hosts. If anywhere, the boundary is where friendship and the welcome given to the stranger (philoxenia) are at home. There might be something methodologically strange about this interweaving between modern and ancient conceptualisations of boundaries and matter and meaning. However, I would argue that a certain strangeness—even a lack of homeliness—is essential in order to remain with the boundary while simultaneously presenting this stone as the core that has remained with us, without remark and unnoticed since the introduction of philosophy into the central market of Athens.

The reader may, I fear, feel a certain disillusionment at the swinging timescale in the following pages. This, however, can be accounted for by the scarcity of early texts and the need to speculate upon changes that preceded the events described by later sources. On the other hand, no epoch exists in a vacuum, neither our own, nor that of the first few centuries of written history. Human activity is not only judged by reference to the present and the past alone but also by reference to the future. Therefore, it is as natural to look forward in order to look back as it is to look back in order to look forward. As Walter Benjamin stated, ‘nothing that has ever happened should be regarded as lost to history.’3 However, that does not mean that what is lost is overtly apparent in the present; rather, the task is to recognise what history, and its authors, have allowed and are in the process of allowing to slip away or leave concealed under thick layers of progressively more forceful interpretations. In my view, history is a significant factor in the composition of authority, and so for the authoritarian regime that we inhabit today to change, history itself must change, dominated as we are by market-based economics and a profitable version of the past as of the present sold to us in order to keep us from resisting.

To find a well-grounded site from which to rebel has always been a challenge, as the first thing dominant forces do when they assume power is to saturate the field, appropriate the land, and devitalise antagonistic elements. The battle is situated; it is over the earth itself and material gains as much as who has the power to enforce a translation of what that matter means. The catastrophic forces of the present can only be averted from a solid foundation, a grounded theory of the limit, fighting for the presence of boundaries in human economic and technological expansion, in antithesis to the prevailing powers that seek to manipulate the biological and geological foundations of life on earth (biometrics and terraforming). Present economies, no longer subject to the old state or ethnic borders, are all equally enslaved to the corporate interests of big tech and demand the highest price both of the human and the nonhuman, from the increasing presence of biotechnology in the facilitation and control of human activities to the exorbitant mineral demand these technologies make upon the surface of the earth. This means that to be a human embedded in the world and to take back our intra-active relation with other beings and things, we must take back our minds and bodies, free them from the technologies that seek to bind them within the limits of corporate and state control and demand the cessation of mining, deforestation, and the uses and abuses of organic beings.

To do this it may well be necessary to outsmart the very devices that control our slavish devotion to the system and discard the habitual and insidious technologies that have insinuated themselves into our lives. It might not be easy to realise these limits, but the alternative is unadulterated totalitarian dystopia. The trends in post-humanism and, of course, trans-humanism, to expand bodily boundaries into apparatuses fail to stress the negative impact such apparatuses might have on the environment and on human dignity.4 The smartphone user might feel at one with her device and revel in the extension of her bodily boundaries to encapsulate this fantastic expansion of her senses, but she turns a blind eye to the mountainside exploded in search of metal or the bushland concreted over to provide a basis for the turbines necessary to charge it, not to mention the fact that every thought, every move she makes is subject to scrutiny. We are all implicated in the expansion of boundaries, and whether this is doing harm to us and the world we live in should be a subject not only of serious debate but should be reason enough to modify our thought, behaviour and limits of consumption. In any case our behaviour will be modified one way or the other, whether we like it or not. Biotechnological companies are keen to sell us products that expand the boundaries of consumption into previously untapped natural resources (including the modification of humanity itself), but ecological devastation (regardless of the colour of the flag flying over the military-industrial complex) will evidently enforce its own boundaries in any number of predictable and as yet unforeseen ways. Both alternatives will come to pass if we are too lazy to discover boundaries for ourselves, and the window of opportunity where we have the choice to change this future is becoming smaller day by day. The only alternative vision I can see that will in any way alleviate the decimation of humans, nature and human nature is by doing away with the belief in and exercise of false boundaries enforced by the power nexus of state, big tech and corporate wealth in order to include us as living beings within a world constituted by the vitality of interactions between all things.

The following chapters each riff upon different lexical meanings or translations of the word horos and provide a discussion centring around different examples of the word, whether in the archaeological record or in classical texts. Chapter One (‘A New Ancient Petrography’) provides an overview of the horos as it appears in the archaeological record and textual tradition. Given that the definition of its verbal cognate is ‘to determine, divide, define,’ it is suggested that this division is in the heart of language itself. Boundary markers must be read or interpreted as such, implying that the boundary is not a reductively material thing but is something dependent upon us, inside of us. Whatever it was that led us to create boundaries—to make distinctions—also bound us to our linguistic distinctions. This is what a materialist disposition would describe us as: the inscribers, the plinth-builders. The horos,at once stone and term, raises the problem of the boundary between nature and human, between worked stone and natural stone. This problem comes down to us in our distinctions of the physical world. In the absence of a demiurge, matter is supposed to be without meaning, and this is the basis for scientific rationalism. However, even the distinction between meaning and matter relies upon a conceptual acceptance that the boundary between the two is in some way naturally given. This chapter raises the problem of such distinctions and claims that any attempt to define humans as separate to everything else always ends up back at the coincidence of word and stone.

Chapter Two (‘Does the Letter Matter?’), taking the definition ‘boundary, landmark[…]pillar (whether inscribed or not)’ as its starting point, returns to the earliest examples of the horos in the archaeological record. Here I confront the Derridean problem of writing as origin. Even if the stone was not marked with the word for boundary (horos), it does not cease to be a boundary because it was nonetheless read as a boundary. Therefore, I turn to the lexicons to discover how the Greeks themselves defined the horos. The result is twofold, like the boundary; a definition of the word must accept the horos as the boundary of writing and reading. It is always inferred in any act of reading because there must be something, whether the inscribed word or the natural rock, for us to read. Horos proliferates from the rock into our definitions of what words mean, and it always remains as the solid foundation of these works of ‘definition.’ It is the difference and bond that is co-terminal with language as such but does not for all that lose its base materiality as stone.

Chapter Three (‘Breaking the Law’) considers the legal implications of the horos, taking the meaning ‘bounds, boundaries.’ The regions that are thus separated are given definition by the boundary and exist as different spaces on account of the boundary but also share something in common: the boundary itself. I return to earlier examples of the boundary-stone in the Hebraic and Greek Biblical tradition, where variations of the horos appear repeatedly and ask the question as to why boundary-stones in the Old Testament required the double enforcement both as stone placed upon the land and as prohibition in the written text. The problem of legality is raised and followed into the work of Plato’s Laws, where the first law is given as the prohibition against the removal of the boundary-stone. In these textual traditions, the prohibition that is to follow upon the horos implies that something has been lost from the base materiality, the bare presence of the stone, and this loss is exactly what supports the force of law. The final knife-twist in the letter of the law is described by a leap into the ephebic military service performed upon the boundaries of Attica, where failure to swear allegiance to the horoi meant exile from the Athenian city and its institutions.

The problem of determinate definition was assumed by Hegel and Heidegger but has been the problem for philosophy ever since Aristotle defined finding the ‘essence’ or being of something as the task of philosophy. The problem is always a terminological one, but we have inherited it also as a problem of translation. This problem belongs to the horos, the question of definition and the necessary overlap between words in both metonymy and metaphor. Chapter Four (‘Terminological Horizons’) focuses upon the translation of horos as ‘term,’ ‘definition,’ ‘determination,’ a sense of the word that is outlined by Aristotle in his Topics and Categories where he provides a definition of horos as the word that means ‘what it is to be.’ If horos (here ‘definition’) is a word that signifies the being of a thing, is it itself retained within the definition of a word even if in the form of a trace of this lithic term? Although the horos as ‘definition’ remains essential within the tradition of Western philosophy, its material presence has been confounded in the attempts at absolute conceptualisation and transcendental reasoning. That said, we do get a brief and telling glimpse of it in the preface to Hegel’s Phenomenology. Its echo remains also in the work of Heidegger, inherited from Husserl, as that which frames our position in the world, as the ‘horizon,’ verbal cognate of the horos.

In Chapter Five (‘The Presence of the Lithic’) I illustrate the indebtedness of the conceptual structure and language of the geologic timescale to the Aristotelian formulation of time. I do not do this to assert that there is a debt modern thought owes to ancient thought but rather to raise the possibility of the divisive nature of the question of time itself. In the geologic timescale, as in Aristotelian time, linearity is important but not unproblematic. How the measurement of time is conceptualised both in geologic and in Aristotelian ‘time’ raises the problem of division in a continuum, or how to break time down into measurable units. For Aristotle the ‘now’ is the term distinguishing the past from the future, brought into alignment with the figure of the horos. Does this temporal boundary still retain a trace of stone? The stone is not only instrumental but also essential to the divisions of geologic time; it is simultaneously the tool and the unit of measure. Here, too, stone is read by us, and it is believed that it can tell us something determinate about the past, something at once concrete and abstract. That stone is given as a figure of the unit of time, interpreted as an indicator of time past, must alert us that the dynamics of existence are always read in material configurations which, as in the geological diagnostic of the Anthropocene, implicate a notion of human conjectural and material hegemony.

In Chapter Six (‘Geophilia Entombed or the Boundaries of a Woman’s Mind’) I return once again to the archaeological record to discover the material remains of the horos. Horos was also inscribed upon the gravestone, a reminder for the living of this most basic of boundaries. Even here a limit remains, for it is only in our translation of the stone into a memorial that conjures up the ghost of the dead. With a study of ancient drama and the role burial rites play in the signification of death, I discover another aspect of the horos. Burial rites have long been associated exclusively with Sophocles’ Antigone and the conflict between two different regimes of justice. Horos is what remains as the trace of our division from nature, and it also marks the futility of this division since we must all and without exception inevitably find a home for ourselves in the earth, inevitably engraving us all in a common fate. In this guise, the horos describes the boundary between the human and the organic world but is also dependent, in the archaic period in particular, on a reciprocal relationship between the living and the dead: I call this the economics of death.

The final chapter (‘Solon’s Petromorphic Biopolitics’) resolves the former discussions on the horos by looking at one last meaning, ‘decision of a magistrate.’ The law-reformer Solon is famous for an act called the seisachtheia, where he was said to have relieved the earth from her burdens and freed men who were enslaved. The burdens he claims to have raised were none other than horos-stones. With the reforms of Solon, the web of meanings that the horos seems to have bound begins to unravel, and yet the word itself does not lose its multiplicity. Solon brings an end to a period of civil war and inaugurates an epoch that ensured the productivity of its citizens, limited their ease of movement, and opened the way to the eventual dominance of the market and its persuasive reasoning. He did so by claiming for himself the middle position: in his own words he stood as a horos in the midst of the people. I argue that this created a fracture in the traditions of Athens, disrupting the household and the place of women and their command over reproduction and production, generating, in contrast, a society based upon a centralised political economy. The novelty of this claim is in the idea of biological productivity as a regulative device within Athenian legal discourse. Therefore, I return to the first example of the horos, found in the Athenian agora, which marks this space for the exclusive valuation of words and things and where the work of exchange can go on because responsibility for the space that it encloses has been deferred. The argument draws to a close with the question of the reiteration of such boundaries and the need to reassert our communal life with things.

1Bennett (2010) ix.

2Foucault (2008) xi.

3Benjamin thesis III, in Löwy (2005) 34.

4Barad (2007) 153ff.

Fig. 1. ΗΟΡΟΣΕΙΜΙΤΕΣΑΓΟΡΑΣ ‘I am the horos of the agora’, IG I³ 1087 [I 5510]. Photograph by M. Goutsourela, 2013. Rights belong to The Athenian Agora Museum © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.R.E.D.)

1. A New Ancient Petrography

© 2022 Thea Potter, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0266.01

ὁρίζω

-divide or separate from, as a border or boundary, separate, delimit, 2. bound, 3. pass between or through, 4. part, divide.

II. mark out by boundaries, limit one thing according to another. 2. trace out as boundary. III. ordain, determine, lay down. 2. define a thing.

IV. Med., mark out for oneself, 2. determine for oneself, get or have a thing determined. 3. define a thing.

1

Define- 1. To bring to an end. 2. To determine the boundary or limits of. b. To make definite in outline or form. †3. To limit, confine. 4. To lay down definitely. †5. To state precisely. 6. To set forth the essential nature of. b. To set forth what (a word etc.) means. 7. transf. To make (a thing) what it is; to characterise. 8. To separate by definition.

2

The ritual significance of the placement and shaping of stone is not uncommon in prehistoric cultures and ancient societies, some of these traditions even continuing into the present. From diverse countries with lithic arrangements ranging in scope and size, any number come to mind: for example, the enormous stone heads of Easter Island, the stone lines of the Aboriginal Australians, the megaliths of the Celts, the stone of Mecca, the obelisks of Egypt and the cute little Mesoamerican mushroom stones. In Greece there was the omphalos stone of Apollo at Delphi and of course all those stone altars and statues of gods. However, there were also the rather more discreet horoi, pretty much limited in range to Athens, Attica and its closest neighbours. Not unlike the stone arrangements found in many other countries and cultures, these were said to be boundary markers of one type or another.

The problem as to whether the site of the boundary can actually be said to be a place, natural or otherwise, is posed and deposed in the double gesture by which the stone assumes or vacates the position. Are these boundaries permanent, do they describe natural boundaries or human boundaries, is their removal punishable, and is their transgression permitted? For example, the erection of the pyramids is attributed both to a mysterious, alien or divine intervention and to the weathered hands of an extensive human labour force, slave or skilled, and yet the stone, presumably, remains the same.3 And while the cobblestones lining the streets of Paris were torn up to aid the indomitable march of modernisation facilitating automobile speed and military access to the inner city, they were also raised in the name of the revolution, grasped at as material for the barricades or simply thrown in desperation against the armed forces. We should not dismiss as accident that this most solid and elementary material finds its place on the threshold between substantiality and insubstantiality, between life and death, comrade and enemy. Nor is it mere chance that the placement and displacement of the stone is characterised by a double gesture, of divinity and labour, construction and destruction.

I consider this a work of vital materialism, as phrased by Bennett, that nonetheless retains the problem of human subjectivity in the question of the boundary that would divide humans from other beings, other matter, and other objects with which we cohabit.4 I argue that any concept of the human is always already caught up in the aporetic structure of the meaning of stone or the matter of meaning. As Barad presented, matter is involved in a two-way creation of meaning, or even a plurality of involved meaning generating relations, where ‘distinct agencies do not precede, but rather emerge through, their intra-action.’5 This entanglement of agencies, taking place for Barad upon the more epistemologically advanced plane of quantum physics, here can be seen to involve similar players and a similar vocabulary. Barad argues that ‘the primary ontological unit is not independent objects with independently determinate boundaries and properties,’ but rather ‘phenomena’ that are defined as ‘the ontological inseparability of agentially intra-acting components.’6 It seems to me that from the horos, found as it is in its various contexts, material, textual and conceptual, it is possible to infer this intra-activity taking place both on the surface of the earth as well as in the minds of humans. This suggests to me that boundary-generating practices are inseparably material and conceptual so that ontology itself is caught up in this aporetic self-referentiality when it calls for the metaphysical independence of determinate boundaries. And no matter how much it tries it always defers to the definition, which in turn defers to the stone and back again to the boundary, in a cyclical dance between the constructs of meaning and materiality.

I elaborate this problem through the coincidence, the literal nexus of stone—boundary—writing. To say that matter is vital does not mean anthropomorphising the organisms and non-organisms, the stones, trees, and bacteria that share our world; rather, for me it means the necessary destabilising of the boundaries between the human and nonhuman and recognising dignity as something that inheres to all things; whether this is done via biology (reinhabiting the human with the microbiome etc), via ecopolitics (recognising the equal distribution of natural resources and the dignity of all beings) or, as is the case here through an intersection of the archaeological, via the ecological and, believe it or not, the classical. The stone that is the subject of this book is the very boundary that suggests the differences and commonalities between these different modes of being.

In this chapter I begin by providing an overview of the horoi in the archaeological record, the actual extant stones with a brief introduction to the translation of their inscriptions. Next, I present a brief excursion into the presence of horoi in the literary corpus, followed by a speculative discussion about their meaning and significance, both for the early archaic period as for today. Finally, this chapter presents an overview of how we comport ourselves ontologically in relation to the nonhuman and how two figures tend to surface (definition and stone) whenever the distinctions between our categories look precariously close to collapsing, breaking up or falling down.

Raising the Stakes

In the surrounds of the ancient Athenian polis, boundary-stones proliferated. Today, in the museums of Athens (and the gardens of the French School of Archaeology), examples of these stones can still be found if you look for them. One of these, found in situ east of the tholos and at the edge of the agora, legibly presents itself: ΗΟΡΟΣΕΙΜΙΤΕΣΑΓΟΡΑΣ, ‘I am the boundary-stone of the agora.’7 The inscription of this stone is conservatively dated to the beginning of the fifth century BC.8 The unearthing of a number of other stones (and one with exactly the same inscription in retrograde) reinforced the notion that these were the remainders of an outline in stone, designating the boundaries of the agora, market-place, and marking off the area within as devoted to the activities of exchange and public speaking. Certain acts such as those that meant a person was deemed atimos (without honour) excluded people from the right to enter the agora,for example patricides and murderers were not permitted entry to the agora.9 However, there were also activities that were not permitted within the agora. Diogenes Laertius tells a story about the controversial cynic Diogenes of Sinope eating within the bounds of the agora.10 The implication is that it was not accepted to eat in the agora, though this may have been more a matter of custom rather than law.While it is known that the boundaries of the agora were for keeping certain actors and actions out, I think it is also worth looking at it the other way around, as boundaries meant for keeping certain activities in. If this is nothing more than a hunch on my part, it is nonetheless a hunch that Karl Marx also entertained as a significant factor in the rise of the capitalist economy and the dissolution of social bonds.

Marx was adamant that the original, or at least the earlier location of exchange was marginal. In Capital he states that ‘the exchange of commodities begins where communities have their boundaries, at their points of contact with other communities, or with members of the latter. However, as soon as products have become commodities in the external relations of a community, they also by reaction, become commodities in the internal life of a community.’11 Again, in the Grundrisse, he says that ‘money and the exchange which determines it play little or no role within the individual communities, but only on their boundaries, in traffic with others.’12 And, in his A Contribution to Political Philosophy, he elaborates further and comes to the conclusion that exchange has a negative effect when it acts from within the community: ‘in fact, the exchange of commodities evolves originally not within primitive communities, but on their margins, on their borders, the few points where they come into contact with other communities. This is where barter begins and moves thence into the interior of the community, exerting a disintegrating influence upon it.’13

The question that Marx would not entertain, however, is whether it is the interiorisation of the processes of exchange that spawns the community’s dissolution or the preternatural force of the boundary itself. If the