23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

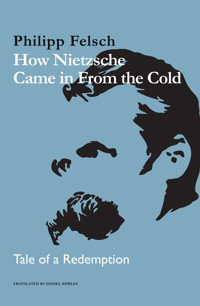

Nietzsche’s reputation, like much of Europe, lay in ruins in 1945. Giving a platform to a philosopher venerated by the Nazis was not an attractive prospect for Germans eager to cast off Hitler’s shadow. It was only when two ambitious antifascist Italians, Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, began to comb through the archives that anyone warmed to the idea of rehabilitating Nietzsche as a major European philosopher.

Their goal was to interpret Nietzsche’s writings in a new way and free them from the posthumous falsification of his work. The problem was that 10,000 barely legible pages were housed behind the Iron Curtain in the German Democratic Republic, where Nietzsche had been officially designated an enemy of the state. In 1961, Montinari moved from Tuscany to the home of actually existing socialism to decode the “real” Nietzsche under the watchful eyes of the Stasi. But he and Colli would soon realize that the French philosophers making use of their edition were questioning the idea of the authentic text and of truth itself.

Felsch retraces the journey of the two Italian editors and their edition, telling a gripping and unlikely story of how one of Europe’s most controversial philosophers was resurrected from the baleful clutch of the Nazis and transformed into an icon of postmodern thought.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 459

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Epigraph

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

The Spoilsports: Introduction

Notes

1 Beyond the Gothic Line: Lucca, 1943–4

The Chosen Few

Standard Positions of Nietzsche Reception

Seduction of Youth

The Blue Light

Magic of Letters

The School of Higher Ignorance

Notes

2 Painstaking Care and Class Warfare: Pisa, 1948

On the Joy of Being Communist

Comrade Job

Le goût de l’archive

Everyone Else’s Nietzsche

Academics in the War of Position

Travels in Germany

Drinking, Smoking, Reading

Notes

3 Operation Nietzsche: Florence, 1958

Off the Beaten Track

Beauty and Horror

The Other Library

Crossing over the Abyss

Dangerous Papers

The Italian Job

Notes

4 Over the Wall and into the Desert: Weimar, 1961

No Suspicious Traces

The Air in Weimar

The Craft of Reading

Nietzsche Is a Disease

The Knight of the Woeful Figure

The Politics of Facts

Down with the Philosophers!

Notes

5 Waiting for Foucault: Cerisy-la-Salle, 1972

Alone against the Nietzsche Mafia

Against Interpretation

Watching TV in Reinhardsbrunn

The Ostracized Thinker

Nietzsche’s Dirty Secret

Death of an Author

Quote Unquote

Notes

6 Burn after Reading: Berlin, 1985

Anarchy of Atoms

The Red Brigades of Textual Criticism

Nietzsche in Paperback

The Great Conspiracy

Philology Degree Zero

The Ring of Being

Notes

Bibliography

Archives

Internet sources

Films

Literature

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

The Musarion luxury edition – presumably also the same edition as Hitler...

Giorgio Colli, 1942

Mazzino Montinari, 1946

The first Italian edition of Nietzsche’s collected works appeared in the ...

The circle and the family: Gigliola Gianfrancesco, Clara Valenziano, Anna Maria,...

Chapter 2

Students in front of the Scuola Normale, Pisa, early 1940s

Ҥ[138]. Past and present. Transition from the war of maneuver (an...

Delio Cantimori with his wife Emma Mezzomonte (center) and an unknown woman, aro...

Montinari in the culture war, 1957

Chapter 3

In the thin air of logic: Angelo Pasquinelli, Giorgio and Anna Maria Colli, Gigl...

Chapter 4

The view from Colli’s room in the Hotel Elephant: “The church in t...

Chapter 5

“ich habe meinen Regenschirm vergessen” – “I forgot ...

Chapter 6

Colli amid the landscape of his longing, Cape Sounion, 1962

What remained of The Will to Power: the 9th subdivision of the Kritische Gesamta...

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

vi

ix

x

xi

xii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

How Nietzsche Came in From the Cold

Tale of a Redemption

PHILIPP FELSCH

Translated by Daniel Bowles

polity

Copyright Page

Originally published as Wie Nietzsche aus der Kälte kam. Geschichte einer Rettung © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München 2022

This English edition © Polity Press, 2024

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

111 River Street

Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5761-5 – hardback

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023941291

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Dedication

for Martin Bauer

Epigraph

I scribble something here

and there on a page while on my journeys,

I write nothing at my desk,

friends decipher my scribblings.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Nietzsche needs no interpreter.

Giorgio Colli

Nietzsche is a disease.

Mazzino Montinari

List of Illustrations

1 The Musarion luxury edition. Friedrich Nietzsche, Gesammelte Werke, vol. 18: Der Wille zur Macht, Munich: Musarion, 1926, title pages

2 Giorgio Colli. Private collection © Chiara Colli Staude

3 Mazzino Montinari. Private collection © Chiara Colli Staude

4 Federico Nietzsche, Così parlò Zarathustra: Un libro per tutti e per nessuno, Milan: Monanni, 1927, title pages

5 Gigliola Gianfrancesco, Clara Valenziano, Anna Maria, Giorgio Colli, Chiara and Enrico Colli. Private collection © Chiara Colli Staude

6 Students in front of the Scuola Normale. Centro Archivistico della Scuola Normale Superiore, fondo Delio Cantimori, raccolta fotografica

7 Antonio Gramsci, Quaderno di carcere, No. 6, § 138, © Fondazione Gramsci. “§<138>. Past and present. Transition from the war of maneuver (and frontal assault) to the war of position – in the political field as well. In my view, this is the most important postwar problem of political theory; it is also the most difficult problem to solve correctly. This is related to the issues raised by Bronstein, who, in one way or another, can be considered the political theorist of frontal assault, at a time when it could only lead to defeat. In political science, this transition is only indirectly related to what happened in the military field, although there is a definite and essential connection, certainly. The war of position calls on enormous masses of people to make huge sacrifices; that is why an unprecedented concentration of hegemony is required and hence a more ‘interventionist’ kind of government that will engage more openly in the offensive against the opponents and ensure, once and for all, the ‘impossibility’ of internal disintegration by putting in place controls of all kinds – political, administrative, etc., reinforcement of the hegemonic positions of the dominant group, etc. All of this indicates that the culminating phase of the politico-historical situation has begun, for, in politics, once the ‘war of position’ is won, it is definitively decisive. In politics, in other words, the war of maneuver drags on as long as the positions being won are not decisive and the resources of hegemony and the state are not fully mobilized. But when, for some reason or another, these positions have lost their value and only the decisive positions matter, then one shifts to siege warfare – compact, difficult, requiring exceptional abilities of patience and inventiveness. In politics, the siege is reciprocal, whatever the appearances; the mere fact that the ruling power has to parade all its resources reveals its estimate of the adversary.” (Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks, ed. and trans. Joseph A. Buttigieg, vol. III: Notebooks 6–8 [New York: Columbia University Press, 2007], 109)

8 Delio Cantimori, Emma Mezzomonte, and an unknown woman. Centro Archivistico della Scuola Normale Superiore, fondo Delio Cantimori, raccolta fotografica

9 Mazzino Montinari. Der Spiegel, April 17, 1957, 23

10 Angelo Pasquinelli, Giorgio and Anna Maria Colli, Gigliola with Andrea Pasquinelli and other relatives. Private collection © Chiara Colli Staude

11 Letter from Giorgio Colli to Anna Maria Musso-Colli, August 24, 1964, Fondazione Arnoldo e Alberto Mondadori, Milano, fondo Giorgio Colli, b. 04, fasc. 026

12Friedrich Nietzsche, jotter N-V-7, page 171, in Friedrich Nietzsche, Digitale Faksimile-Gesamtausgabe, edited by Paolo D’Iorio, Paris, Nietzsche Source, 2009–, www.nietzschesource.org/DFGA/N-V-7,171. Copyright © Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv, 2016

13 Colli at Cape Sounion. Private collection © Chiara Colli Staude

14 Friedrich Nietzsche, Werke, Sec. 9: Der handschriftliche Nachlaß ab Frühjahr 1885 in differenzierter Transkription, vol. 2: Notizheft N VII 2, Berlin: De Gruyter, 2001, 193f.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the employees at the Goethe and Schiller Archive in Weimar and at the Fondazione Mondadori in Milan – and especially to Maddalena Taglioli at the Centro Archivistico della Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa. My gratitude goes to Alessandra Origgi for her transcriptions and to Wolfert von Rahden and Bettina Wahrig-Schmidt for their references. Wolfram Groddeck helped in deciphering Nietzsche’s notebooks. Chiara Colli Staude gave her friendly support. To all of them I offer my heartfelt thanks. For their critical reading and important suggestions, I thank Andreas Bernard, Jan von Brevern, David Höhn, Yael Reuveny, and Martin Bauer, who provided the impetus for this book.

THE SPOILSPORTSIntroduction

In July 1964 at Royaumont, a former Cistercian abbey located north of Paris, a German–French summit meeting took place. The year prior, de Gaulle and Adenauer had signed the Élysée Treaty. As though feeling an obligation to the spirit of that friendship accord, the two nations’ leading expositors of Nietzsche were now meeting to discuss the correct interpretive reading of his works. In hindsight, Royaumont is considered one of the events that inaugurated the postmodern era in French philosophy. The participants could not have foreseen, however, that their convention would one day be thought of as the germinal moment of a new Zeitgeist. During his lifetime, Nietzsche himself had wanted to be regarded as an “unfashionable” thinker, but only in the second postwar era following his death did this wish seem finally to come true. To be sure, he had been acquitted of the charge of National Socialism by Georges Bataille, and he had appeared in Camus and Sartre as a kind of remote precursor to existentialism. But the next big thing in France was structuralism. In the two German states, prospects looked even worse for the author of Zarathustra. In the German Democratic Republic (GDR), he officially rated as a “pioneer of fascism,” and in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), too, his reputation had plunged to a historic nadir. If those diagnosing the times are to be believed, he had lost his core audience, the so-called “youth of today.” The skeptical generation no longer had any use for his pathos. As late as 1968, Jürgen Habermas wrote, with palpable relief, that “nothing contagious” now emanated from Nietzsche.1

It is fitting that the majority of the speakers at Royaumont were Nietzsche veterans from the first half of the century: Boris de Schlözer, for instance, the eighty-three-year-old scion of the Russian branch of a German noble family, who spoke about the transfiguration of evil in Nietzsche and Dostoevsky. Or Jean Wahl, the Jewish Sorbonne professor who had been incarcerated during the German occupation and who at Royaumont, as honorary chairman of the Société française d’études nietzschéennes, played the role of a convivial figurehead. Or Karl Löwith, who, unlike anyone else, managed to personify the Nietzsche enthusiasm from the first half of the century, for he had, after all, experienced it first-hand; from the youth movement, to the euphoria around the world war and his studies with Heidegger, to the day the National Socialist racist laws put an end to his academic career in Germany, Nietzsche had been the lodestar of his own radical school of thought. Without this “last German philosopher,” Löwith later wrote in his autobiography, drafted in Japanese exile, “the development of Germany” could not be understood – and in a turn of phrase redolent of the mood of many a scholar of the humanities today, he added with remorse that he heedlessly “contributed to the destruction.”2

At Royaumont, the erstwhile avant-gardist had transformed into a white-haired stoic who was no longer intrigued by Nietzsche’s theory of the will to power, but rather by his thought of the eternal return. Löwith argued for exiting the disastrous upheaval of modernism and returning to a classical equanimity that viewed humankind as part of the forever-immutable cosmos.3

Nothing could be more anathema to the French Young Nietzscheans comprising the other half of the conference attendees than this loftily standoffish conservatism. While Löwith showed the balance of an epochal disenchantment, they were already rehearsing the themes of a future philosophy of transgression. For Gilles Deleuze, attaché de recherches at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique and organizer of the colloquium, what the eternal return called to mind was in no way the contemplation of the ever-constant cosmos, but a Dionysian principle of upheaval that guaranteed the world never remained identical with itself.4

One of these young Frenchmen was Michel Foucault, who at the time, just like Deleuze, did not yet enjoy considerable renown. The fact that his lecture on “Nietzsche, Freud, Marx” is the only one still read today might be because he assumes the perspective of a second-order observer. Indeed, instead of adding another interpretation to those by the Nietzsche expositors, he made his object of inquiry interpretation as such. Well into the nineteenth century, Foucault argued, the practices of textual exegesis were limited by the regulative notion of an authentic source text. It was Nietzsche – and Freud and Marx – who cut this comforting ground from under hermeneutics with their writings. By replacing the idea of the original text with an abyss of interpretations nested inside one another, Nietzsche, in particular, transformed for his successors the business of interpretation into an infinite task no longer backed by an originary truth.5

The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche’s first book, which appeared in print in 1872 and simultaneously heralded the beginning of the end of his academic career, has an unusual dramatic structure. Readers must first follow the dialectic of the Apollonian and Dionysian for twelve chapters before – halfway through the text – Socrates, the actual protagonist, finally enters onto the narrative stage. Or more precisely: he does not enter the stage where the god of dreams and the god of ecstasy celebrate their tension-filled unification in the form of ancient tragedy, but instead sits inconspicuously among the audience, where, together with his sympathetic comrade, the poet Euripides, he eyes what transpires, full of misgivings. The worldview that underlies tragedy remains incomprehensible to him. Unlike the others present, Socrates embodies “theoretical optimism,” the ethos of Enlightenment science, the belief that it was possible “to separate true knowledge from semblance and fallacy” and to escape the tragic hero’s fate with existential slyness. The real drama Nietzsche unfolds in the second half of his book is not between Dionysian and Apollonian principles, but between Dionysian and Socratic ones.6

It was with the same skepticism and the same unobtrusiveness as Socrates and Euripides that Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari must have sat among the philosophers assembled at Royaumont. They have left virtually no trace among the records of the conference’s discussions. Aside from the short lecture Montinari delivered on the morning of the second day, not one query, not one hypothesis, not so much as a single marginal comment of theirs has survived. And yet they must have lodged their objection after Foucault’s lecture on unregulated interpretation at the very latest. As their correspondence in the run-up to the conference reveals, however, they felt out of place among the Nietzsche experts. Colli, who in his mid-forties taught ancient philosophy as an adjunct professor at the University of Pisa, normally gave academic functions a wide berth, and Montinari, who in his time as an operative of the Italian Communist Party had grown accustomed to dividing the world into friends and foes, was afraid the “bigwigs of Western Nietzscheology” wanted to make an example of him. Even on the bus from Paris to Royaumont, they chanced to overhear a French professor inquiring of an Italian colleague about the identity of the two unknown Italians whose names appeared in the program. They belonged to none of the camps represented at the colloquium, they felt no affinity for either the German Apollonians or the French Dionysians, and in the coffee breaks, which are inescapable at such events, they surely stood around largely by themselves. “The many, and among them the best individuals, had only a wary smile for him,” Nietzsche writes about Euripides the skeptic, and the pair of Italians may have fared similarly.7 In the eyes of the Nietzscheologists, to be sure, they played an ignominious role; they had come to Royaumont as spoilsports.

What one must also bear in mind is that this German–French exchange of ideas was burdened with a troubling legacy. In the late 1950s, as a result of publications by Darmstadt philosophy professor Karl Schlechta and French Germanist Richard Roos, it had come to light in both Germany and France in quick succession that the respective Nietzsche editions issued by the Nietzsche Archive in Weimar under the aegis of Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche contained posthumous interventions and manipulations, even falsifications. There had not been a solid textual foundation since that time.8

The body of research on what is perhaps the most famous scandal in more recent philosophical history now fills a small library unto itself. Erich Podach, one of the many Nietzsche scholars to weigh in on the debate then, wrote that Nietzsche was the “most severely distorted figure in modern literary and intellectual history with respect to his life and works.” And while one may, with good reason, cast doubt on this assertion, it is true that there may hardly be another instance of literary and philosophical inheritance in which this suspicion plays so crucial a role.9

For reasons subject to continual speculation, Nietzsche had suffered a mental breakdown in Turin toward the beginning of 1889 and spent the following decade until his death in 1900 largely under the care of his mother and sister, who, along with guardianship over him, had gained power of disposition over his published and unpublished oeuvre. To be sure, the image of the money-grubbing sister ruled by the anti-Semitic obsessions of her deceased husband and personally profiting from the celebrity of her mentally ill brother has since yielded to a more nuanced appraisal. Credit is nevertheless due to Elisabeth, who from the outset endured exceptional mistrust for her role as female executor of the estate, for having chased after Nietzsche’s scattered Nachlass, or literary remains, down to the last scrap of paper that bore his handwriting and, as George disciple Rudolf Pannwitz wrote in Merkur in 1957, for having “hurled [his message] into the world at the seminal moment.” That she did not shrink from telling strategic lies all the while, that she possessed the criminal energy to suppress, alter, and falsify documents, and that she offered up her brother to the völkisch Right and the National Socialists, however, remains equally true. Under his sister’s direction, no fewer than four different complete editions were launched. She herself became influentially active in publication, parlayed Weimar’s Nietzsche Archive into a national pilgrimage site, and contributed decisively to the transformation of her brother into the icon with a mustache that he remains – among everything else – to this day.10

Elisabeth’s campaign essentially turned on the fact that she had secured for herself the copyright to Nietzsche’s Nachlass in 1896. By placing snippets and teasers in newspapers, she kept interest alive in the fast-growing Nietzsche community. With the publication of The Will to Power in 1901, the year after Nietzsche’s death, she unveiled the purported magnum opus his adherents had long been waiting for. Her efforts ended up fomenting belief in an esoteric tradition that surpassed in significance those writings published during his lifetime – a belief which according to Schlechta’s and Roos’s revelations was to be regarded as a fiction.11

While Der Spiegel devoted a ten-page lead story to the affair in the culture section, the majority of philosophers brushed it off like a pesky nuisance. Heidegger, who himself had been involved in the preparations for a historical, critical edition of the complete works as a consultant to the Nietzsche Archive in the 1930s, declared that The Will to Power remained for him as ever the definitive reference. Even Schlechta, who had edited the incriminated book’s aphorisms into a corrected, chronological order, voiced opposition to the need for a completely new edition. Toying with such thoughts, moreover, seemed purely hypothetical to most of those concerned anyway since, as Rudolf Pannwitz, cited above, had written, Nietzsche’s Nachlass “in the Eastern Zone” – in the GDR, that is – was beyond the reach of all well-intentioned friends of Nietzsche until further notice.12

Montinari was the sole conference participant in attendance from the “Eastern Zone.” When the invitation from Deleuze arrived, he was about to relocate his place of residence to Weimar. In those days, anyone who moved from Tuscany to the GDR had to have good reasons. In Montinari’s case, these reasons dated back to a day in April 1961. While the rumor was still circulating among quite a few West German Nietzscheans that Nietzsche’s Nachlass had been loaded onto a Soviet truck after the war and ended up in Moscow’s catacombs, it was on this day – four months before the Berlin Wall was built – that Montinari, who still maintained good contacts in the GDR from his time as a party functionary, entered the Goethe and Schiller Archive in Weimar to consult Nietzsche’s manuscripts. Is it an exaggeration to suggest that he never got over this experience? “This journey to Weimar is perhaps the most important event of my life,” he wrote a few days later to Colli. “I was moved in a very peculiar, ineffable way when I held a manuscript of Nietzsche’s in my hands for the first time.”13

Nietzsche himself had fled from Thuringia to Italy via waypoints in Switzerland and France. Under the spell of Nietzsche’s manuscripts, Montinari chose the opposite path. As a matter of fact, in Weimar he had only wanted to check the textual basis for an Italian translation, planned together with Colli, yet after his return they decided to edit a new German-language edition of Nietzsche’s complete published and unpublished writings. While Colli used his media contacts to drum up financial backers and publishers, Montinari began deciphering Nietzsche’s Nachlass on site in Weimar – a task that would occupy him until the end of his life. As Nietzsche had written in the preface to Dawn, he wanted to be read “slowly, deeply, with deference and caution, with ulterior motives, with doors left open, with delicate fingers and eyes.” In Montinari, he found his perfect reader. “He is perhaps the only person among the living who has read every surviving line, every preserved missive in the original,” Frank Schirrmacher, the literary section editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, wrote shortly before Montinari’s death in 1986.14

There is a sense of astonishment at the outset of this book not unlike that of the French professor on the bus to Royaumont. Who were the two Italian dilettantes, and how did they end up editing Nietzsche’s writings? What was the source of their commitment to the work of a philosopher who in the 1960s – especially for leftists – was still an ambassador of evil? Colli and Montinari were an improbable pair in multiple respects: a bourgeois independent scholar with philhellene obsessions and, twelve years his junior, an apostate foot soldier of the Communist Party with a proletarian family background. Their mutual acquaintance extended back to the 1940s, to the Tuscan town of Lucca, where Colli had been Montinari’s high school philosophy teacher. “The one taciturn, aristocratic, captivated by the radiance of a distant past; the other vivacious, electrifying, empathetic, preoccupied by the present and its transformation,” wrote Antonio Gnoli, who devoted a series of insightful portraits to the two in the daily La Repubblica.15

Not even in their enthusiasm for Nietzsche did they jibe with one another. While Colli saw in Nietzsche a modern-day mystic who enabled him to flee to an imaginary Greece, Montinari viewed him as a radical figure of enlightenment, a proponent of inconspicuous insights won through methodological stringency. In Montinari’s letters, one can trace the gradual metamorphosis of a communist intellectual into a philologist. Did his fidelity to the text provide him with ultimate stability after the loss of his political conviction? “All luxury leaves him unmoved, he only wants to work,” reported the informal collaborator surveilling Montinari at the Goethe and Schiller Archive for the Ministry for State Security. Amid the cultural and political acceleration of the 1960s, it was the very doldrums behind the Wall that made possible the staying power of this epic deciphering project in the first instance. To Montinari, Weimar seemed to have fallen “out of time.” There, of all places, in an educated middle-class enclave of actually existing socialism, the maverick found his personal posthistoire. Transcribing a single page from Nietzsche’s notebooks could take days. After the reading room closed, Montinari would immerse himself in autodidactic study of the theoretical and technical details of editorial philology. In time he arrived at the conclusion – characteristic when dealing with sacred scriptures – that in Nietzsche’s texts “not one image, not one word, not even one punctuation mark in lieu of another” was random. He intended to ignore the arguments over his worldview and get back to the “genuine Nietzsche.” What drove him, he wrote to Colli, was a “raging passion for the truth.”16

It was with this sensibility – and full of reservations about these philosophers fond of interpretation – that Colli and Montinari traveled to Royaumont in 1964. No wonder the encounter was colored by mutual distrust; while the “bigwigs of Western Nietzscheology” grappled with the correct interpretation, the two Italians staked their claim to represent the authentic Nietzsche. Colli, who liked reading his texts as one might listen to an “unknown music,” held the opinion that anyone who attempted to interpret Nietzsche did him the first injustice. Lacking an academic title or pertinent publications but equipped with the authority of his first-hand knowledge, Montinari in his lecture detailed the deficiencies of existing editions. He went so far as to suggest a moratorium on interpretation until philological questions under dispute were resolved. Instead, however, Michel Foucault called for wild exegesis. If indeed no authoritative foundation in the form of an Urtext existed, then there was no alternative but to indulge in ever more novel readings. “The only valid tribute to thought such as Nietzsche’s is precisely to use it, to deform it, to make it groan and protest,” he explained a few years later. “And if commentators then say that I am being faithful or unfaithful to Nietzsche, that is of absolutely no interest.”17

This sounds like French theory, to whose global success story Nietzsche the author owes his lasting renaissance up through the present day: as a theorist of transgression, as a pioneer of “absolute encoding” and all manners of Deconstruction. This French Nietzsche could not have been more alien to Colli and Montinari’s intentions. In their deference to literality, their philological ethos, and their belief in truth, they were evocative of figures from a distant past when compared with Foucault and Deleuze. In their claim to represent the definitive Nietzsche, their edition intruded like an atavism into the landscape of late twentieth-century theory. Even Heidegger, who is said to have disparagingly termed their Kritische Gesamtausgabe [Critical Complete Edition] Nietzsche’s “Communist edition,” saw the spirit of the nineteenth century at work in philology. He felt “a revulsion at this thoroughness and rummaging,” he had written in the 1930s before withdrawing from the advisory body of the historical-critical edition – not without adding that Nietzsche himself would have felt “a much greater one.”18

To be sure, no one may have contributed more to the affect against philology in the German-speaking world than Nietzsche, who within the span of a few years had gone from a promising talent to a renegade of his field: ancient philology. Not even as a young professor in Basel had he been able to resist sneering at the insipidness of his colleagues: “Improving texts is entertaining work for scholars [. . .]; but it should not be regarded as too important a matter,” one reads in the notes for the never-published fifth Unfashionable Observation, the title of which was to be “We Philologists.” Later, too, after the end of his academic career, the love–hate relationship with his discipline never left him: philology was “science for cranks,” “repetitive drudgery,” and “intellectually middle class.” In his autobiography Ecce homo, he wrote that the “junk of dusty scholarship” had ensured intellectual stagnation for ten years of his life.19 Today, when the discipline at best occupies a marginal position within the humanities and has gone from a flagship subject to a rare and exotic one, the energy Nietzsche invested in his feud comes off as oddly over-ardent. In the course of its momentous loss of importance, little more seems to have remained of philology, in spite of all provisional attempts to salvage it, than its bad reputation.20

Why, then, tell the story of Colli and Montinari, which leads, to quote Nietzsche once more, straight through the “dust of bibliographic minutiæ”? Whoever opens one of the volumes of commentary from the Kritische Gesamtausgabe enters a desert of philological exactitude in which variants and preliminary stages are listed, citations and sources are identified, and punctilious descriptions of Nietzsche’s manuscripts are given. “Nietzsche’s aggressive intelligence apprehended by means of the most tedious pedantry,” Schirrmacher once wrote about the two Italians’ endeavor.21 All the admirable meticulousness notwithstanding, does it not constitute a betrayal of Nietzsche’s thought?

Much has been written about the irony inherent in the fact that Nietzsche of all people, that spurner of philology, has become the object of a philology so excessive. The circumstances of his transmission history and the character of his writings – aphoristic and marked by contradictions and constant revisions – have, on the one hand, made him into a Protean figure among modern philosophers. It would be difficult to find another body of work in the history of European thought that proved so adaptable to all imaginable interpretations: right-wingers and leftists, enthusiasts and skeptics, dictators and democrats have all invoked Nietzsche, and none of them had trouble producing the textual passages appropriate to his reading. Perhaps because he himself acted out the antagonistic tendencies of his age, Nietzsche played the role of a canvas onto which the entire spectrum of twentieth-century ideas could be projected.22

On the other hand, the promiscuity of his writings has given cause, time and again, for what might be termed a “philological caveat”: every audacious reading, every claim to explicate the actual meaning of his thought, is met by the converse promise to reconstruct the “genuine,” authentic Nietzsche freed from all post-hoc “legends,” by bringing to light his buried, misconstrued, or repudiated Urtext. The thicket of interpretations thus stands in opposition to an almost equally confusing abundance of editions on the basis of which the history of Nietzsche’s influence may be divided into periods. One almost has the impression he had to be edited anew each time in order for him to be interpreted anew – and vice versa.23

In this way, The Will to Power, the magnum opus compiled by his sister and the showpiece of the editions issued under her direction, dominated the Nietzscheology of the first half of the century, which sought the central idea, the systematic nexus, the philosophical essence of his aphoristic style. In Alfred Baeumler, Nietzsche became an apologist of power, in Karl Löwith, a denier of the linear temporal order of the modern age, while Heidegger conferred on him the final starring role in the drama of Western forgetfulness of being. It was Jürgen Habermas who in 1968 pointed out the paradox that only unsystematic thought possessed the requisite flexibility to be compatible with such different systematic schemata.24

Habermas’s verdict coincided with the rise of the second wave of Nietzsche enthusiasm; centered in Paris, its perspective on Nietzsche’s writings was one of diametrical opposition to preceding approaches. Within the attempts to conceptualize his oeuvre, the need to reappraise the ideological writer as a philosopher to be taken seriously had always been articulated as well. In contrast, Nietzsche’s French interpreters, from Deleuze to Derrida, perceived the true explosive power of his thought to be located precisely in its aphoristic fragmentation, in its lack of a central viewpoint, in its transgression of the order of philosophical discourse. With this theoretical revision comes a philological one; the textual basis for the French Nietzsche was provided by Colli and Montinari’s edition, which was published concurrently. Throughout the 1970s, the poststructuralist Nietzsche debate reads at times like a commentary on their editorial project. Despite contrary intentions and mutual animosity, Italian philology and French theory converged at a common intellectual sensibility. “Philology is in league with myth: it blocks the exit,” Theodor W. Adorno wrote regarding the futility inherent in insisting on naked literality in the face of unpopular readings. Colli and Montinari were not spared this insight either. “Today one can say,” Montinari wrote after encountering the first Zarathustra graffiti on the walls of the University of Florence during the “autonomous” turmoil of 1977, “that a new myth is forming around Nietzsche, lumping together elements of conservative ideology with some of leftist theory. Our edition has contributed significantly to this resurgence.”25

Anyone who wishes to tell the story of this resurgence and this edition holds one inestimable advantage: they can draw upon the correspondence between Colli and Montinari, which, interrupted by briefer and longer pauses, spans four decades, from the 1940s to the 1970s – the documentation of an erotically charged teacher–student relationship, the Bildungsroman of two Italian intellectuals, and an intimate journal of an editorial project. As reflected in this correspondence, the “repetitive drudgery” of editorial philology loses any sort of technical routine and becomes a matter of existential and political relevance. On the basis of his biography, a large portion of Italy’s postwar history can be reconstructed, Adriano Sofri, founder of Lotta Continua, remarked after Montinari’s death.26 Yet not just that of Italy: with the Kritische Gesamtausgabe, a chapter of Cold War intellectual history comes into focus as well. Undergirded by the intimate insights that Colli and Montinari’s letters afford, this book pursues a perhaps all too ambitious enterprise: cracking the cover of their edition a second time, but this time with the aim of releasing four decades of affective, intellectual, and political energies that lie stored within its sober critical apparatus.

Notes

1

In order to reduce the number of endnotes, several citations will be combined into each note. First come the direct citations and verbatim quotations – in the order in which they appear in the body text – then secondary literature. The “youth of today” in Edgar Salin, “Der Fall Nietzsche,”

Merkur

112 (1957): 573. Jürgen Habermas, “Nachwort,” in

Erkenntnistheoretische Schriften

, by Friedrich Nietzsche (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1968), 237. The participants in the similarly groundbreaking 1966 conference “The Language of Criticism and the Sciences of Man” in Baltimore were also unaware of the significance of their meeting. Cf. Jacques Derrida, “Some Statements and Truisms about Neologisms, Newisms, Postisms, Parasitisms, and Other Small Seismisms,” in

The States of “Theory”: History, Art, and Critical Discourse

, ed. David Carroll, trans. Anne Tomiche (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), 80. On the situation in France, see François Dosse,

History of Structuralism

, trans. Deborah Glassman, vol. 1 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 202ff.

2

Karl Löwith,

My Life in Germany before and after 1933: A Report

, trans. Elizabeth King (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 6, 145. On Jean Wahl, cf. Jacques Le Rider,

Nietzsche en France: De la fin du XIX

e

siècle au temps présent

(Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1999), 183.

3

Cf. Löwith,

My Life in Germany

, 83, as well as, for greater detail, Löwith’s lecture given at Royaumont, “Nietzsches Versuch zur Wiedergewinnung der Welt,” in

90 Jahre philosophische Nietzsche-Rezeption

, ed. Alfredo Guzzoni (Königstein: Hain, 1979), 89–102. The contradictions between Löwith’s cosmological and ethical exegesis of the eternal return are pointed out by Urs Marti,

“Der große Pöbel- und Sklavenaufstand”: Nietzsches Auseinandersetzung mit Revolution und Demokratie

(Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, 1993), 277.

4

Gilles Deleuze, “Conclusions on the Will to Power and the Eternal Return,” in

Desert Islands and Other Texts: 1953–1974

, by Gilles Deleuze, ed. David Lapoujade, trans. Michael Taormina (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2004), 123.

5

Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Freud, Marx,” in

Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology

, ed. James D. Faubion, trans. Jon Anderson and Gary Hentzi,

Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984

, vol. 2 (New York: New Press, 1998), 269–78.

6

Friedrich Nietzsche,

Kritische Studienausgabe

, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, vol. 1 (Munich/Berlin: De Gruyter, 1988), 100 (hereafter

KSA

). On the book’s dramatic structure, see Peter Sloterdijk,

Thinker on Stage: Nietzsche’s Materialism

, trans. Jamie Owen Daniel (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989). The unusual composition also arose because the book is comprised of two originally separate lines of thought. Cf. Mazzino Montinari, “Nietzsche lesen,” in

Nietzsche lesen

, by Mazzino Montinari (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1982), 5.

7

Mazzino Montinari in a letter to Giorgio Colli dated August 17, 1963, quoted in Giuliano Campioni,

Leggere Nietzsche: Alle origini dell’edizione Colli-Montinari

(Pisa: Edizioni ETS, 1992), 280.

KSA

, 1988, 1: 81. The experience on the bus in Mazzino Montinari, “Presenza della filosofia: Il significato dell’opera di Giorgio Colli,”

Rinascità

, February 16, 1979, 42.

8

Cf. Karl Schlechta, “Philologischer Nachbericht,” in

Werke in drei Bänden

, by Friedrich Nietzsche, ed. Karl Schlechta, vol. 3 (Munich: Hanser, 1956), 1383–432. Richard Roos, “Les derniers écrits de Nietzsche et leur publication,”

Revue Philosophique

146 (1956): 262–87.

9

Erich Podach,

Friedrich Nietzsches Werke des Zusammenbruchs

(Heidelberg: W. Rothe, 1961), 430. Karl Löwith offers criticism in his review of this book, reprinted as “Rezension von Erich Podach, Nietzsches Werke des Zusammenbruchs und Ein Blick in die Notizbücher Nietzsches,” in

Sämtliche Schriften

, by Karl Löwith, vol. 6:

Nietzsche

(Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, 1987), 510–17.

10

Rudolf Pannwitz, “Nietzsche-Philologie?,”

Merkur

117 (1957): 1076. Essential for the history of his sister and that of the Weimar Nietzsche Archive: David M. Hoffmann,

Zur Geschichte des Nietzsche-Archivs: Chronik, Studien und Dokumente

(Berlin: De Gruyter, 1991). A more recent biography worth reading: Ulrich Sieg,

Die Macht des Willens: Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche und ihre Welt

(Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag, 2019).

11

Cf. Schlechta, “ Philologischer Nachbericht,” 1403; Richard Roos, “Règles pour une lecture philologique de Nietzsche,” in

Nietzsche aujourd’hui?

, ed. Centre culturel international de Cerisy-la-Salle, vol. 2:

Passion

(Paris: Union générale d’éditions, 1973), 287. In general, Stefan Willer,

Erbfälle: Theorie und Praxis kultureller Übertragung in der Moderne

(Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, 2014), 161–92. The teaser in Salin, “Der Fall Nietzsche,” 574f.

12

Cf. Martin Heidegger,

Nietzsche

, trans. David Farrell Krell, vol. 1 (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1979), 9. Schlechta, “Philologischer Nachbericht,” 1403. Pannwitz, “Nietzsche-Philologie?,” 1084.

13

Montinari in a letter to Colli dated April 8, 1961, quoted in Giuliano Campioni, “Mazzino Montinari in den Jahren von 1943 bis 1963,”

Nietzsche-Studien

17 (1988): XVf.

14

KSA

, 1988, 3: 17. Frank Schirrmacher, “Nietzsches Wiederkehr,”

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

, September 19, 1986. For the figure of the “absolute reader,” cf. Hans Blumenberg, “Das finale Dilemma des Lesers,” in

Lebensthemen: Aus dem Nachlaß

, by Hans Blumenberg (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1998), 29–33.

15

Antonio Gnoli, “Gli angeli di Nietzsche,”

La Repubblica

, April 28, 1992. Montinari contrasted his “sanguine” temperament with Colli’s “melancholic” one in a letter to the latter dated November 17, 1967, fondo Montinari, cartella 13, Archivio Scuola Normale Superiore.

16

Mündlicher Bericht des GI “Gießhübler” vom 16.1.1970

, 1970, BArch, MfS Erfurt, 542/78, A, Bundesarchiv, Stasi-Unterlagen-Archiv Berlin Mitte. Giorgio Colli in a letter to Anna Maria Musso-Colli, September 14, 1962, fondo Giorgio Colli, b. 04, fasc. 024, Archivio Mondadori. Mazzino Montinari, “L’onorevole arte di leggere Nietzsche,”

Belfagor

41 (1986): 338; Montinari in a letter to Giorgio Colli, May 9, 1962, fondo Colli, b. 32, fasc. 185.003, Archivio Mondadori. Montinari to Colli in a letter dated August 22, 1963, quoted in Campioni,

Leggere Nietzsche

, 281. On Montinari’s interpretation, see Wolfram Groddeck, “Nietzsche lesen,”

Nietzscheforschung

25 (2018): 31–9.

17

Giorgio Colli,

Distanz und Pathos: Einleitungen zu Nietzsches Werken

, trans. Ragni Maria Gschwend and Reimar Klein (Hamburg: Europäische Verlagsanstalt, 1993), 12f. Cf. Giorgio Colli,

Dopo Nietzsche

, Milan: Adelphi, 1974, 26. Michel Foucault, “Prison Talk,” in

Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977

, ed. and trans. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 53f. On a similar note, see Roland Barthes,

S/Z

, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill & Wang, 1974), 15: “The work of the commentary [...] consists precisely in

manhandling

the text.” Montinari’s suggestion in Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, “État des textes de Nietzsche,” in

Nietzsche

, Cahiers de Royaumont 6 (Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1967), 128. Walter Kaufmann,

Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist

, 3rd ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968). Even by the third edition of Kaufmann’s influential study one may read: “The International Nietzsche Bibliography does not list any contributions by any of the two editors” (483).

18

Gilles Deleuze, “Nomadic Thought,” in

Desert Islands and Other Texts: 1953–1974

, by Gilles Deleuze, ed. David Lapoujade, trans. Michael Taormina (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2004), 254. Heidegger’s derogatory comment, according to John Rajchman, “Deleuze’s Nietzsche,” Nietzsche 13/13, October 25, 2016:

http://blogs.law.columbia.edu/nietzsche1313/john-rajchman-deleuzes-nietzsche/

. Heidegger in a letter to Richard Leutheußer dated January 12, 1938, quoted in Alfred Denker et al., eds.,

Heidegger und Nietzsche

(Freiburg: Verlag Karl Alber, 2005), 26. Cf. Heidegger,

Nietzsche

, 1: 10.

19

KSA

, 1988, 8: 23. Nietzsche in a letter to Paul Deussen, dated from the second half of October 1868, in

Sämtliche Briefe: Kritische Studienausgabe

, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, vol. 2 (Munich/Berlin: De Gruyter, 2003), 329 (hereafter

KSB

).

KSA

, 1988, 8: 32. Friedrich Nietzsche,

The Joyful Science: Idylls from Messina, Unpublished Fragments from the Period of The Joyful Science (Spring 1881–Summer 1882)

, trans. Adrian Del Caro,

The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche

, vol. 6 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2023), 250 (hereafter

CW

);

KSA

, 1988, 3: 624. Nietzsche,

CW

, 2021, 9: 269;

KSA

, 1988, 6: 325. On Nietzsche’s relationship to his field, see Christian Benne,

Nietzsche und die historisch-kritische Philologie

(Berlin: De Gruyter, 2005). On the consequences of his falling-out for the humanities, see Wolf Lepenies, “Gottfried Benn – Der Artist im Posthistoire,” in

Literarische Profile: Deutsche Dichter von Grimmelshausen bis Brecht

, ed. Walter Hinderer (Königstein: Athenäum, 1982), 330.

20

Cf. James Turner,

Philology: The Forgotten Origins of the Modern Humanities

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), ix. On philology’s poor reputation in France, see Bernard Cerquiglini,

In Praise of the Variant: A Critical History of Philology

, trans. Betsy Wing (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), chap. 4. More recent attempts at rehabilitating philology include Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht,

The Powers of Philology: Dynamics of Textual Scholarship

(Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003); Thomas Steinfeld,

Der leidenschaftliche Buchhalter: Philologie als Lebensform

(Munich: C. Hanser, 2004); and Turner,

Philology

.

21

KSA

, 1988, 1: 268. Schirrmacher, “Nietzsches Wiederkehr.” On the significance of this edition in the history of philosophical text editions, cf. Michel Espagne,

De l’archive au texte: Recherches d’histoire génétique

(Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1998), 153.

22

On irony, see Ludger Lütkehaus, “‘Ich schreibe wie ein Schwein’: Die neue Nietzsche-Gesamtausgabe lässt den großen Stilisten aussehen wie einen Kritzler,”

Die Zeit

, January 5, 2006. On Nietzsche as a battleground for antagonistic tendencies, see Ernst Nolte,

Nietzsche und der Nietzscheanismus

(Frankfurt am Main: Propyläen, 1990), 10f. The projection surface in Habermas, “Nachwort,” 238.

23

On the philological reservation, cf. Steven E. Aschheim,

The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany, 1890–1990

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 15. Incidentally, the perpetuated “return to the origin” is what, according to Foucault, distinguishes a “founder of discursivity.” Cf. “What Is an Author?,” in

Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology

, ed. James D. Faubion, trans. Robert Hurley,

Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984

, vol. 2 (New York: New Press, 1998), 219. On the importance of the editions, in general, for the history of Nietzsche’s reception, see Eckhard Heftrich, “Zu den Ausgaben der Werke und Briefe von Friedrich Nietzsche,” in

Buchstabe und Geist: Zur Überlieferung und Edition philosophischer Texte

, ed. Walter Jaeschke et al. (Hamburg: F. Meiner, 1987), 117. Among the German-language editions are: the

Klein-

and

Großoktav-Ausgabe

; the

Musarion-

, the

Beck-

, and the

Schlechta-Ausgabe

; the apocryphal legacy editions, like Baeumler’s

Unschuld des Werdens

[

Innocence of Becoming

], Würzbach’s

Vermächtnis Friedrich Nietzsches

[

Legacy of Friedrich Nietzsche

], or Podach’s

Nietzsches Schriften des Zusammenbruchs

[

Nietzsche’s Writings of Breakdown

]; the countless anthologies still multiplying today, the mass-market, popular, and study editions, as well as the definitive editions launched in recent years by the publishers Stroemfeld and Steidl; and finally, having now grown to over forty volumes and available in German, Italian, French, Japanese, and English versions, the

Kritische Gesamtausgabe

by Colli and Montinari, which represents the gold standard of international Nietzsche research to this day. “Each kind of edition engenders a new author” (Henning Ritter, “Es gibt ihn nicht mehr, den gefährlichen Nietzsche,”

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

, March 19, 2002).

24

Habermas, “Nachwort,” 237f.

25

Theodor W. Adorno, “Bibliographical Musings,” in

Notes to Literature

, by Theodor W. Adorno, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 304. Mazzino Montinari, “Erinnerung an Giorgio Colli,” in

Distanz und Pathos: Einleitungen zu Nietzsches Werken

, by Giorgio Colli, trans. Ragni Maria Gschwend and Reimar Klein (Hamburg: Europäische Verlagsanstalt, 1993), 170.

26

Referring to the correspondence, Michel Espagne speaks of the “roman d’une édition” (“novel of an edition”),

De l’archive au texte

, 154. Cf. Adriano Sofri, “Federico il pendolare,”

Panorama

, February 22, 1987, 139. A similarly motivated investigation of “political philology” is undertaken by Robert Pursche, “Philologie als Barrikadenkampf: Rolf Tiedemann und die Arbeit für Walter Benjamins Nachleben,”

Mittelweg 36: Zeitschrift des Hamburger Instituts für Sozialforschung

30, no. 3 (2021): 12–40.

1BEYOND THE GOTHIC LINELucca, 1943–4

For Mussolini’s sixtieth birthday on July 29, 1943, Hitler gifted him a complete edition of Nietzsche, bound in blue pigskin. “Adolf Hitler to his dear Benito Mussolini,” read the Führer’s handwritten dedication in the first volume. The book shipment made its way across the Alps in time for the big day, but Field Marshal General Kesselring, Commander in Chief South stationed with the Italian high command in Frascati, near Rome, found himself incapable of delivering it personally because all attempts to locate the Duce had failed. A group of conspirators from the Fascist Grand Council had deposed him four days before his birthday and had taken him to an undisclosed location under the pretense of providing for his safety.1

Not until August did German intelligence operatives learn that Mussolini was being held captive on the island of Ponza, in the Tyrrhenian Sea. Accompanied by a note from Kesselring wishing him “a bit of joy,” the Führer’s gift was sent on to him by the new Italian government. According to Mussolini’s notoriously unreliable memoirs, Nietzsche did in fact make the days of his imprisonment more bearable. Did he feel transported back to the beginnings of his political career when he had learned German specifically in order to read Nietzsche in the original? Was he comforted by Nietzsche’s maxim “live dangerously!,” which had been the slogan of his young movement in the 1920s? In order to prevent his liberation by the Germans, the Duce was taken from one hideout to the next. Only when the rebels relocated him to the Abruzzi did the Nietzsche edition remain behind on the isle of La Maddalena, north of Sardinia. In September, when Hitler put Italy under occupation, a Wehrmacht detachment is said to have been tasked with recapturing the volumes, but the story goes that the officer responsible obtained a revocation of the order by pointing out the expected casualties. A luxury set of Nietzsche volumes from Mussolini’s personal library with a dedication from Hitler: there could scarcely be more striking proof of Nietzsche’s political discreditation. But the edition’s trail goes cold on La Maddalena. Its current whereabouts are unknown.2

The Chosen Few

Giorgio Colli also recommended his pupils read Nietzsche in German – at least those he met outside of class. After his arrival in Lucca as a teacher of philosophy and Greek at the Ginnasio N. Machiavelli in the autumn of 1942, it did not take long for him to gather a circle of devotees around him. At the beginning of the school year, he had surprised the students by asserting that philosophy was neither about juggling abstract notions, nor about memorizing classical systems of thought – and as though to prove this conviction, he displayed a provocative nonchalance toward the official syllabus.3

We must also bear in mind that philosophy instruction in fascist Italy was no minor matter. A former journalist, the Duce himself had a soft spot for intellectual speculations. The field owed its defining gain in prestige, however, to philosophy professor Giovanni Gentile, who had defected from the bourgeois-liberal camp to the fascist one in the early 1920s and been rewarded by Mussolini with the post of Minister of Education for doing so. Gentile had seized the opportunity to bolster the historical, literary disciplines over the scientific ones and to introduce as a principal subject a new manner of philosophy instruction tailored exactly to the profile of his own thought. He championed an idealism inspired by Hegel and Fichte according to which reality consisted of nothing but the “pure act” of cognition. He understood the world as the process of a consciousness gradually coming into its own, all while bringing about the beautiful, the true, and the good, and tasked philosophy classes with making pupils aware of this progress of Reason in its astonishing rigor, from its beginnings with the Greeks to its political realization in the “ethical state” of fascism.4

Giorgio Colli, by contrast, proclaimed Hegel anathema – a battle cry with which he fell between two stools, for Hegelianism, or storicismo as they called it in Italy, was not limited to Gentile’s loyalist variant. Benedetto Croce, Gentile’s adversary and the voice of antifascist Italy, also preached the grand narrative of the world-historical progress of Reason – even though in his version this process led not to Mussolini, but to a liberal state. Between Gentile and Croce there was no escape. With their Hegel-based systems, these two hostile dioscuri delimited the space of what was conceivable. The Prussian privy counselor Carl Schmitt, who had traveled to Rome in 1936 to lecture on the “total state” at the Italian–German Cultural Institute, was amazed at the soundness of his hosts’ knowledge of Hegel. Even the Duce apparently assured him during an audience he was a staunch Hegelian. Mussolini’s enthusiasm for Nietzsche had long since cooled; one might get the idea that Hitler chose the wrong gift seven years later.5

Without a doubt, Colli would have agreed with this supposition. While storicismo represented the false whole, for him Nietzsche’s thought constituted the way out. According to Benedetto Croce, history was the “last religious faith” left to the modern subject. “Whosoever does not close his heart to historic sentiment,” he had written, was “no longer alone,” but united with the “spirits at work on earth before him,” indeed, “with the life of the universe.” It was notions like these that Nietzsche fought against half a century earlier. Colli delighted in citing Nietzsche’s polemic against historicism from the second Unfashionable Observation, “On the Utility and Liability of History for Life,” in which he had denounced the cult of historical education as a symptom of a dying culture. Although written as a reckoning with the history-obsessed climate in the Second German Empire, the text struck the Italian Zeitgeist