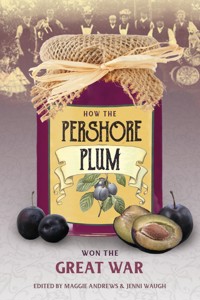

How the Pershore Plum Won the Great War E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The First World War was won not just on the battlefields but on the Home Front, by the men, women and children left behind. This book explores the lives of the people of Pershore and the surrounding district in wartime, drawing on their memories, letters, postcards, photographs, leaflets and recipes to demonstrate how their hard work in cultivating and preserving fruit and vegetables helped to win the Great War. Pershore plums were used to make jam for the troops; but ensuring these and other fruits and vegetables were grown and harvested required the labour of land girls, Boy Scouts, schoolchildren, Irish labourers and Belgian refugees. When submarine warfare intensified, food shortages occurred and it became vital for Britain to grow more and eat less food. Housewives faced many challenges in feeding their families and so in 1916 the Pershore Women's Institute was formed, providing many women with practical help and companionship during some of Britain's darkest hours in history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 182

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Map of Pershore in 1914. (Jenni Waugh)

To our mothers,

grandmothers and the

women who brought

them up.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book has been produced and written by and with many people and groups in and around Pershore, who have researched, discussed, explored and learnt about the history of Pershore in the First World War. They include:

• Pershore Heritage and History Society: Cynthia Johnson (Chair), Roy Albutt, Nancy Fletcher, Heather Greenhalgh, Jean and Tom Haynes, Audrey Humberstone, Margaret Tacy.

• Pershore Women’s Institute: Audrey Whitehouse (President), Maureen Speight, Viv Breed, Eileen Rampke, Beth Milsom, Jean Barton.

• Croome Park Volunteer: Susanne Atkin.

• Pershore Civic Society: Judy Dale (Chair).

• Pershore Town Council: Ann Dobbins (Clerk), Tony Rowley (Mayor of Pershore 2014–2016).

• Pershore Library (Worcestershire County Libraries Service): Emma Powell and Helen Faizey.

• Postgraduate and undergraduate history students from the University of Worcester who provided research support and helped out at events, Jess Ball, Darren Tafft, Elspeth King, Emily Linney, Emmanuel Newman, Kenny Peterson, Nikki Primer, Phillip Rose.

The research has been supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund’s (HLF) ‘First World War: Then & Now’ grant programme, the University of Worcester, and the Voices of War and Peace: The Great War and its Legacy WWI Engagement Centre funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

The HLF’s ‘First World War: Then & Now’ funding stream provides grants of between £3,000 and £10,000 for community groups to research, conserve and share the often unrecorded local heritage of the First World War (www.hlf.org.uk/looking-funding/our-grant-programmes/first-world-war-then-and-now). In 2015, HLF awarded grants to both the Pershore Heritage and History Society and the Pershore Women’s Institute for a two-year community history project: WW1 in the Vale. For further information about the WW1 in the Vale project and for stories we could not fit into this book, see our blog: ww1inthevale.wordpress.com. The HLF also supports the Worcestershire World War 100 Project (www.ww1worcestershire.co.uk/).

The AHRC-funded ‘Voices of War and Peace: the Great War and its Legacy First World War Engagement Centre’ is led by the University of Birmingham and works in partnership with the HLF to offer research support and guidance to community groups around the First World War in general and in particular around the following themes: Belief and the Great War, Childhood, Cities at War, Commemoration, Gender and the Home Front (www.voicesofwarandpeace.org).

We are indebted for several of the images in this book to the late Dr Marshall Wilson, who was born in Pershore in 1931. He joined his father as a GP in Pershore and retired in 1991. One of his great interests was research into local history, tracing families and properties back as far as he could. Many Pershore people gave him old photos of forebears or local places and events and these form part of his legacy to Pershore – the Marshall Wilson Collection.

Many of the images, stories and items mentioned in this book can be viewed at the Pershore Heritage Centre, in the Town Hall, Pershore. The Centre is run by volunteers from the Pershore Heritage and History Society and is open from April to October. For full access details see the Society’s website: www.pershoreheritage.co.uk/.

This is not a definitive history of Pershore in the First World War, but a starting point, which we hope will enthuse people in the town and in other rural areas to find out more about some of the very varied and often forgotten histories of life on the home front during this conflict.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

About the Editors

Introduction

1 War Comes to Pershore

Emily Linney and University of Worcester History Students

2 Growing Food in the Market Gardens and Farms of Pershore

Pershore Heritage and History Society and University of Worcester History Students

3 Who is Bringing in the Harvest?

Pershore Heritage and History Society and University of Worcester History Students

4 How Women Kept the Home Fires Burning

The Pershore Women’s Institute

5 Preserving Fruit and Making Jam

Susanne Atkin

6 Not All Jam and Jerusalem: Pershore Women’s Institute

The Pershore Women’s Institute

7 Pershore’s Children at War

Emily Linney and University of Worcester History Students

8 Life Goes on in Pershore

Pershore Heritage and History Society and University of Worcester History Students

Further Reading

Copyright

ABOUT THE EDITORS

PROFESSOR MAGGIE ANDREWS is a cultural historian at the University of Worcester. Her research and publications explore women and domesticity in Britain in the twentieth century focusing particularly on the home front in the First and Second World Wars. She leads the theme of ‘Gender and the Home Front’ for the Voices of War and Peace: The Great War and its Legacy WWI Engagement Centre funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and is the historical advisor to the BBC Radio 4 drama Home Front.

JENNI WAUGH is a freelance archivist and historian who works with heritage organisations and community groups across the West Midlands to uncover the histories hidden in their localities. Significant projects include BBC People’s War, World of Kays and Abberley Lives. She is currently working with Pershore WI, Pershore Heritage and History Society, and the University of Worcester on WW1 in the Vale (HLF-funded) and Volunteers & Voters (AHRC-funded).

INTRODUCTION

Pershore is a small market town in South Worcestershire, bordered to the east and south by the River Avon. The elegant Georgian architecture of the main street is evidence of a time when stagecoaches stopped at the many taverns on the road from Worcester to Evesham and London. Just over 100 years ago, in 1911, the town had a population of a little over 4,000 people, swollen on market day when many of those who lived in the surrounding villages and the nearby Vale of Evesham came to Pershore to sell their produce, visit the doctor or shop in the bustling high street.

Four miles to the west lies Croome Park, family seat of George, ninth Earl of Coventry, Lord Lieutenant of Worcestershire, and his wife Blanche, both of whom took an active role in events of both the town and the county, although they were both in their seventies.

Pershore High Street. (Marshall Wilson Collection)

Croome Park today. (Susanne Atkin)

The Earl and Countess of Coventry. (From a supplement to the Worcester Herald, 30 January 1915)

At the outbreak of the First World War, Pershore Abbey dominated the skyline of the town, as it still does. The abbey, which dates back to the eleventh century, houses Pershore’s memorial to the First World War, a striking bronze statue of Immortality atop a slender column covered with names. Most cities, towns and villages have some sort of memorial – a hall, a park, or most commonly, a stone or bronze statue or tablet, often situated in the market square or at a prominent junction – and almost all bear a list of those who sacrificed their lives fighting in the First World War. However, this conflict was not only fought in the battle-torn lands, skies or seas of Flanders, Serbia, Egypt, Italy or Turkey but also in the factories, kitchens and fields on the home front. When the servicemen went to war other men, women and children were left behind who worried and waited, and worked hard in agriculture and industry, in their homes, in their towns and villages. Without their efforts the conflict would have had a very different outcome.

This book explores what life was like for the residents of Pershore and the surrounding district in wartime. People such as Sydney Falkner, a carter in his thirties, who cultivated 10½ acres of land, and his mother Eliza, who ran the New Inn in Pershore, or Miss Gertrude Annie Chick, a 37-year-old dressmaker living in Wisteria Cottage, or Mrs Jane Twivey, the 60-year-old wife of a farm labourer, who lived in New Road. Sidney, Gertrude, Jane and many others had their lives disrupted and utterly altered by the conflict, for, as will be discussed later in the book, they not only tried to keep the ‘home fires burning’ but they also produced, preserved and prepared the food with which both the nation and the army were fed. Without their efforts, and those of millions like them, Britain could not have won the First World War.

Pershore Abbey. (Jenni Waugh)

Aerial view of Pershore in the mid-twentieth century. (Pershore Heritage Centre)

Britain in the early twentieth century was far from self-sufficient in food, having instead a heavy reliance on imports. Nearly 80 per cent of the country’s grain, an essential ingredient in bread, the staple food in the working-class diet, was imported from the USA.1 Two thirds of the sugar, both an important preservative and source of energy, came from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The first few days of the war saw panic buying, price rises and shortages that became more intense as war progressed. The threat to merchant shipping and food imports caused by the increasing ferocity of submarine warfare in 1917 led to shortages and lengthy queues for food. The following year rationing was introduced in Britain for the very first time. The weekly allowance for each person was 15oz (425 grams) of meat, 5oz (142 grams) of bacon, and 4oz (113 grams) of butter or margarine.2 Sugar was rationed although bread was not, and there was increasing pressure on the public to eat less bread. These strictures required the whole population to eat less food and the rural population to increase the amount they produced to feed both the armed forces abroad and the civilian population at home. Servicemen fighting overseas had to be supplied with 3,000 calories per man per day. Farmers in Pershore, like others across the country, increased grain production during the conflict, but the smallholders and fruit-growers of the district had another, more significant, role to play in feeding the nation and its fighting forces.

The War Memorial in Pershore Abbey. (Jenni Waugh)

Families picking plums in Pershore. (Marshall Wilson Collection)

In the early twentieth century, Pershore, Evesham and the villages of the Vale were famous for growing fruit and vegetables. The surrounding hills of Malvern, Bredon and the Cotswolds protected the area from the wind and in Pershore the temperature was usually found to be a little higher than in neighbouring counties. These conditions enabled fruit to ripen up to one month earlier than elsewhere. Pershore was particularly renowned for its local plums, which had been developed in the nineteenth century by grafting new varieties onto fruit trees growing in the ancient Tiddesley Woods to the west of the town. The Pershore Purple was a small, tart plum, ideal for bottling, canning and pickling. The large yellow Pershore egg plum was particularly useful for jam making and provided the key ingredient for the apple and plum jam provided to the troops at the Front, which became notorious during the conflict.

Over 4,000 acres of land in Worcestershire were dedicated to plum growing in the pre-war era and Pershore was particularly well appointed to play a major role in fruit production and preservation during the conflict. Two jam and pulping factories were in operation in the town by 1914. Pershore station was on the main line between Hereford and London Paddington, and it was therefore easy for growers to transport fruit, vegetables and jam quickly to other major conurbations such as Birmingham and Bristol. Indeed, in 1906 one of the leading local growers had observed, ‘We have an almost perfect train service to every part of the kingdom’.3

As the fresh produce left Pershore by rail, so a wide range of newcomers arrived at the station: Belgian refugees, prisoners of war, Boy Scouts, university students, schoolboys. All manner of volunteers came to assist in the cultivation and harvest of fruit and vegetables needed to win the war.

The importance of Pershore plums was trumpeted around the world, as can be seen from this article, which was published in a newspaper in Nelson, New Zealand:

GIRLS IN THE PLUM TREES

Plum and Apple jam has become a standard joke in the army, and considering that hundreds of tons of it are consumed every day by our troops it is rather interesting to hear where the vast quantity of fruit comes from.

I (a correspondent in a London Journal) used to wonder until I went plum picking in Worcestershire and realised that three quarters of this beautiful county is given up to the cultivation of the fruit. Devonshire, Somersetshire and Herefordshire may claim the apples but Worcestershire has no rival for plums.

Harvesting Pershore plums. (Marshall Wilson Collection)

Like many similar jobs now successfully accomplished by women, in pre-war days it was considered ‘men’s work’ but if the women did not do it now ‘Tommy’ would be without his jam ration. The slight element of danger makes it all the more fascinating.

There are numberless varieties of plums which come into season quickly one after the other, but those which make the best jam are the ‘Pershore’ or ‘Yellow Egg’ kind. Some of the fruit trees grow tall and straight with long, thin, wavering branches which are not easy to reach; some are thick and bushy; some grow like date palms and are very difficult and rather dangerous to pick; others are so dense that the branches scratch our faces and uproot our hair.

The first thing we had to learn was how to ‘set’ our ladders properly. It is courting disaster to trust in the trunk of plum trees, and we need to choose the thickest and leafiest bough and plant our ladders nearly upright against it, so the combined weight of ourselves and the ladder is rested principally on the ground, and not the bough itself.

As both hands were required for picking the fruit we fastened very large baskets round our waists by leather straps when we went up the trees. The baskets were then emptied into sacks which had to contain 60lbs of the fruit, and these we dragged along the lines between the trees to be ‘weighed up.’ There must often have been ‘fruit pulp’ ready at the bottom of the sacks after we had pulled them over the rough and stony ground.

The Nelson Evening Mail, 16 November 1918

This account from 1918 reflects the experience of many fruit-pickers throughout the war, both local residents and volunteers from out of town. To find out how the Pershore fruit trade became so renowned, this book will begin by looking at how this small market town was affected by the outbreak of war and how farmers struggled to meet the challenge of increasing food production when many young men had gone to fight a war. The changes the conflict brought to ordinary people’s lives will then be discussed, the need to preserve the fruit and, finally, how the war affected the lives of women and children.

This book is about one small community in Worcestershire,4 and yet it is about so very much more than that. It is about the need to imagine what it was like to live through the First World War on the home front. For across the country there were thousands of residents in rural towns and villages producing food and knitting socks, just as they did in Pershore and the Vale of Evesham. They all played a unique, although often forgotten, part in winning the war.

NOTES

1 P.E. Dewey, British Agriculture in the First World War (Oxford: Routledge 1989, reprinted 2014)

2 L.M. Barnett, British Food Policy During the First World War (Oxford: Routledge 1985, reprinted 2014)

3 R.C. Gaut, A History of Worcestershire Agricultureand Rural Evolution (Worcester: Littlebury Press, 1939)

4 M. Andrews, A. Gregson and J. Peters, Voices of the First World War: Worcestershire’s War (Stroud: Amberley Press, 2014)

1

WAR COMES TO PERSHORE

Emily Linney and University of WorcesterHistory Students

The First World War began on 4 August 1914 and according to the Evesham Journal, Europe was faced with the ‘most tremendous war in the history of the world’, which meant that ‘she has been forced to take up arms’. The consequences of the conflict were felt immediately in the town: Pershore Horticultural Show was abandoned and, at the Abbey Church, special prayers were offered for peace at the Sunday service. A round-up of local news reported:

POSITION IN PERSHORE

Preparations are making rapid strides to provide for families whose breadwinners are serving in the war. It is a noticeable fact that considering the size of the town, an unusually large number of men have gone to serve their King and country. They include members of the outdoor staff of the Post Office who were on reserve, a police officer, several men from the Atlas Works and a large number of market gardeners. Many are holding themselves to be called upon at any moment, and others from local banks have volunteered for various branches … Many ladies are busily preparing themselves to go as nurses under the Red Cross Association being members of the local First Aid Detachments. Other ladies are assisting in making shirts and other garments for the soldiers.

Worcester Herald, 15 August 1914

Recruitment

Until conscription was introduced in 1916, the men in the armed forces who were sent to fight had all volunteered to join.1 During August and September 1914, a number of recruitment drives took place in earnest in Pershore, intended to increase their number. Lord Coventry, who had been appointed Lord Lieutenant of the county in 1891 and Honorary Colonel of the Worcestershire Regiment in 1900, took an interest in all matters military. On the day war was declared, he took part in an ‘interesting ceremony at Croome Park’:

NEW COLOURS FOR WORCESTER REGIMENT

Lord Coventry, the honorary colonel, presented new colours on Tuesday to the 5th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment, who have for some time been in camp on his lordship’s estate, Croome Park. The ceremony was shorn of much of its effectiveness by the weather, heavy downpours occurring during the parade and on the return march to camp …

The new colours presented on Tuesday were dedicated by the Rev. W.W. Veness. and were handed to the officers by Lord Coventry, who was accompanied by the Countess of Coventry, Viscount Deerhurst and the house party.

He addressed the battalion, stating […] the record of the regiment’s service was one of which the county might well be proud … They all hoped sincerely that recruiting might be helped.

Gloucestershire Echo, 5 August 1914

In the days following this ceremony, soldiers already enlisted drilled in the town, and were inspected by Lord Coventry, in the hope that this would ‘stimulate’ many young fellows to ‘offer themselves for their country’. It was envisaged that once the harvests had been gathered more young men would be free to join up. Veterans of the Boer War, such as Mr Hugh Mumford, volunteered again for service. A large recruitment meeting was held at the Music Hall, source of much of the popular entertainment in the town, where, only months earlier, German pianist Isabel Hirschfeld had been welcomed to play a benefit concert for the Boy Scouts.

RECRUITMENT MEETING AT PERSHORE

A meeting was held at the Music Hall on Tuesday evening being called by the joint Parish Councils of Holy Cross and St Andrew’s for the purpose of aiding recruitment in the district. The room was packed … The platform was perfectly decorated with flags. Lord Deerhurst [Lord Coventry’s eldest son and a serving soldier] was greeted with applause, said they were meeting to get recruits for Lord Kitchener’s Army. For years we had been proud to think we had a voluntary system (hear, hear). We said if England wanted men there were millions who would lay down their lives for her. It was up to people to demonstrate that this was a fact. The country was in need of young men …

Poster for the Isabel Hirschfield concert at the Music Hall. (Jenni Waugh)

Admiral Cuming in a rousing speech said the war was the greatest ever known. We have been forced into it to protect a weaker nation like Belgium, and England was calling every man must do his duty.

Mr T.W. Parker said that as a man who took part in the public life of the district he would like to say a few words. He did not think they needed words, for he had good faith in the young men of Pershore and district. He appealed to the young men to come forward and join.

Col A.H. Hudson said he was sure Pershore men would respond to the appeal for recruits. There had been more than 90 recruits from Pershore district during the last few days … The Rev. F.R. Lawson, Rector of Fladbury, said he would ask the forgiveness of the speakers on the platform when he said they should honour not so much the men who made great speeches as the lad who went and fought for his country and mother who let him go. (Applause). At the close of the meeting, a large number gave in their names to enlist in the various branches of the Army.

The Music Hall as it is today. (Roy Albutt)

EXCELLENT RESPONSE AT PERSHORE

A large number of able-bodied men have offered themselves for service. The Recruiting Officer, Sgt J.J. Cook, has been inundated … Batches of about 30 per day have been dispatched to Norton Barracks for transfer to various depots. The recruits have, with few exceptions, come up to the standard demanded, and have been conveyed to the railway station in motor cars kindly lent by gentlemen in the district.

Worcester Herald, 12 September 1914