6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

How to Read a Folktale offers the first English translation of Ibonia, a spellbinding tale of old Madagascar. Ibonia is a folktale on epic scale. Much of its plot sounds familiar: a powerful royal hero attempts to rescue his betrothed from an evil adversary and, after a series of tests and duels, he and his lover are joyfully united with a marriage that affirms the royal lineage. These fairytale elements link Ibonia with European folktales, but the tale is still very much a product of Madagascar. It contains African-style praise poetry for the hero; it presents Indonesian-style riddles and poems; and it inflates the form of folktale into epic proportions. Recorded when the Malagasy people were experiencing European contact for the first time, Ibonia proclaims the power of the ancestors against the foreigner. Through Ibonia, Lee Haring expertly helps readers to understand the very nature of folktales. His definitive translation, originally published in 1994, has now been fully revised to emphasize its poetic qualities, while his new introduction and detailed notes give insight into the fascinating imagination and symbols of the Malagasy. Haring’s research connects this exotic narrative with fundamental questions not only of anthropology but also of literary criticism.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

HOW TO READ A FOLKTALE

A Merina performer of the highlands. Photo by Lee Haring (1975).

World Oral Literature Series: Volume 4

How to Read a Folktale: The Ibonia Epic from Madagascar

Translation and Reader’s Guide by

Lee Haring

http://www.openbookpublishers.com

© 2013 Lee Haring; Foreword © 2013 Mark Turin

This book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license (CC-BY 3.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work. The work must be attributed to the respective authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Lee Haring, How to Read a Folktale: The Ibonia Epic from Madagascar. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2013. DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0034

Further copyright and licensing details are available at:

http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254053

This is the fourth volume in the World Oral Literature Series, published in association with the World Oral Literature Project.

World Oral Literature Series: ISSN: 2050-7933

As with all Open Book Publishers titles, digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website at:

http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254053

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-06-0

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-05-3

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-909254-07-7

ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-08-4

ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-09-1

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0034

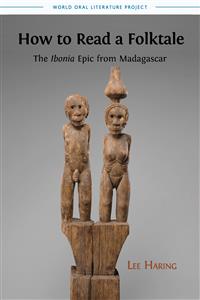

Cover image: Couple (Hazomanga?), sculpture in wood and pigment. 17th-late 18th century, Madagascar, Menabe region. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace, Daniel and Marian Malcolm, and James J. Ross Gifts, 2001 (2001.408). © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. CC-BY-NC-ND licence.

All paper used by Open Book Publishers is SFI (Sustainable Forestry Initiative), and PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Schemes) Certified.

Printed in the United Kingdom and United States by Lightning Source for Open Book Publishers, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Contents

Foreword to Ibonia

Mark Turin

Preface

1. Introduction: What Ibonia is and How to Read it

2. How to Read Ibonia: Folkloric Restatement

3. What it is: Texts, Plural

4. Texture and Structure: How it is Made

5. Context, History, Interpretation

6. Ibonia, He of the Clear and Captivating Glance

There Is No Child

Her Quest for Conception

The Locust Becomes a Baby

The Baby Chooses a Wife and Refuses Names

His Quest for a Birthplace

Yet Unnamed

Refusing Names from Princes

The Name for a Perfected Man

Power

Stone Man Shakes

He Refuses More Names

Games

He Arms Himself

He Is Tested

He Combats Beast and Man

He Refuses Other Wives

The Disguised Flayer

An Old Man Becomes Stone Man’s Rival

Victory: “Dead, I Do Not Leave You on Earth; Living, I Give You to No Man”

Return of the Royal Couple

Ibonia Prescribes Laws and Bids Farewell

Appendix: Versions and Variants

Text 0, “Rasoanor”. Antandroy, 1650s. Translated from Étienne de Flacourt (1661)

Text 2, “Ibonia”. Merina tale collected in 1875–1877. James Sibree Jr. (1884)

Text 3, Merina tale collected in 1875–1877. Summary by John Richardson (1877)

Text 6, “The king of the north and the king of the south”. Merina tale collected in 1907–1910 at Alasora, region of Antananarivo. Translated from Charles Renel, Charles (1910)

Text 7, “Iafolavitra the adulterer”. Tanala tale collected in 1907–1910 in Ikongo region, Farafangana province. Translated from Charles Renel (1910)

Text 8, “Soavololonapanga”. Bara tale, ca. 1934. Translated from Raymond Decary (1964)

Text 9, “The childless couple”. Antankarana tale, collected in 1907–1910 at Manakana, Vohemar province. Translated from Charles Renel (1910)

Text 14, “The story of Ravato-Rabonia”. Sakalava, 1970s. Translated from Suzanne Chazan-Gillig (1991)

Works Cited

Index

Supplementary material

The original versions of many of the texts translated in this volume are provided on the website associated with this volume: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254053

Foreword to Ibonia

Mark Turin1

Two decades after it was first published, a powerful oral epic from Madagascar is once again available to a global readership, in print and online. How to Read a Folktale: The Ibonia Epic from Madagascar is the story of a story; a compelling Malagasy tale of love and power, brought to life by Lee Haring.

Throughout this carefully updated text, Haring is our expert guide and witness. He provides helpful historical background and deep exegesis; but he also encourages us to let Ibonia stand alone — deserving of attention in its own right — a rich example of epic oral literature. And it is through this exquisite rendering of Malagasy orature that we — the readers — appreciate once again the value of oral literature for making sense of human culture and cognition.

Until someone wrote it down (around 1830), Ibonia was communicated only orally. And some 160 years later, Haring transcribed and translated it, introducing the epic in print form to a global audience through Bucknell University Press. Somewhat perversely, while the epic itself remained timeless, the medium of its transmission was endangered. Cultural forms endure and transform, but books simply go out of print.

At an important juncture in the tale, the splendidly named Ratombotombokatsorirangarangarana [Able to Withstand False Accusations] turns to his parents and says: “So long as this tree is green and healthy, I will be all right. If it withers, it means I am in some danger; if it dries up, it means I shall be dead”. As for nature, then, so for literature and culture. As long as the Ibonia epic remains in circulation and use, whether orally in Madagascar, in print through our committed partners — the Cambridge-based Open Book Publishers — or online in the ever-present cloud, we will be able to celebrate the human creativity that it encapsulates.

1 Mark Turin is the Director of the World Oral Literature Project (http://oralliterature.org/).

Preface

This book is a complete rewriting of an earlier translation, published for scholars in 1994. It owes its existence to the distinguished scholar and critic Ruth Finnegan, who pointed me to Open Book Publishers, and to Alessandra Tosi and Mark Turin, who made the new book possible by their willingness to publish in Open Access. A rewriting was prompted by the discoveries of François Noiret (1993) and his review of the earlier book in Cahiers de Littérature Orale (1995). An exhilarating class of highly capable undergraduates at the University of California at Berkeley demonstrated to me that retranslating would be a feasible plan. I am grateful for a second chance to make a rare piece of world literature available to the English-speaking world.

My research in Malagasy folklore began in 1975–1976, when I had the honour of serving the University of Antananarivo (then the University of Madagascar) as Fulbright Senior Lecturer in American Literature and Folklore. University colleagues and librarians and the staff of the American Cultural Center in Antananarivo were unfailingly helpful. Subsequent research in Paris and London was supported by the Research Foundation of the City University of New York and by membership in a summer seminar of the National Endowment for the Humanities. John F. Szwed, who led the seminar, has been a constant inspiration to my thinking. Numerous others have encouraged my work, including Louis Asekoff, David Bellos, Dan Ben-Amos, Jacques Dournes, Marie-Paule Ferry, Melita R. Fogle, Henry Glassie, Alison Jolly, Susan Kus, Frans Lanting, César Rabenoro, Pierre Vérin, Robert Viscusi, and Susan Vorchheimer. Cristina Bacchilega gave very helpful suggestions for the introduction.

This book, like its predecessor, is dedicated to my beloved son Timothy Paul Haring.

1. Introduction: WhatIboniaisand How to Read it

I introduce to you a longish story containing adventures, self-praise, insults, jokes, heroic challenges, love scenes, and poetry. Here I answer two questions: “What is it?” and “How do I read it?” You might decide it is a love story featuring the hero’s search and struggle for a wife, or a wondertale emphasising supernatural belief and prophecy, or a defence of conjugal fidelity, or an agglomeration of psychoanalytic symbols, or a symbolic exposition of the political ideology of a group of people you do not know anything about. You would be right every time.

One way of interpreting Ibonia, perhaps a way to begin reading it, is to think of it as a fairy tale. It is fictional. It includes encounters with the supernatural and a diviner who is clairvoyant. It includes magic charms and magic objects. The hero’s endurance is tested, and he successfully rescues the princess from his rival. Other elements in Ibonia that are common in folktales include magic talismans, which give the hero advice (as birds and animals do in fairy tales); a transformation combat (as in the British folksong “The Two Magicians”), and a set of extraordinary companions (as in Grimm tale no. 134, “The Six Servants”). As in most fairy tales, the time when the action occurs is not specified. Though it does not open with a formula like “Once upon a time”, it closes with an etiological tag. And like all folklore, it exists in variant forms. It was read as a fairy tale by its first non-Malagasy readers, who like ourselves could only perceive it in the terms or categories provided to them by their culture. Ibonia is more complicated than the tales we grew up with. Below, I take up its non-fairy-tale features and show why it should be called an epic.

1.1 Madagascar

The world’s fourth largest island lies in the Indian Ocean, 260 miles from Mozambique on the East African coast. It was settled by waves of Indonesian emigrants from across the Indian Ocean during the sixth to ninth centuries C. E., at a time when the Swahili civilisation of East Africa was also developing. The convergence of Indonesians and Africans created early Malagasy civilisation, including the language in which Ibonia was performed.

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0034.01

2. How to Read Ibonia: Folkloric Restatement

How shall a text so foreign be read, understood, or appreciated? I discovered one path in the library of what was then called the Université de Madagascar, where I was a visiting professor in 1975–1976. On the shelves I found, unexpectedly, quantities of available, published knowledge about Malagasy folklore. The university library and national library held scores of texts, unanalysed, uninterpreted. These called out to me. Faced by so many tales, riddles, proverbs, beliefs, customs, so much folklore to think about, I devised a way of reading the pieces. I decided to read the poems and stories, and even the ethnographic observations on them, as if they were the scripts of plays — as if I could hear them being performed by a living voice. I call this method “folkloric restatement”, meaning reading a printed text and imagining it in performance. Others have discovered the method independently. For instance, the Swedish folklorist Ulf Palmenfelt dug into archive material to reconstruct imaginatively an interview between a nineteenth-century researcher and his aged informant. That is the method I suggest to readers of this book. Imagine a performer, an audience, and a social setting: adults and children sitting around under a tree in the evening. That is how folklore is communicated — through performance. History, seen in print, comes to life through folkloric restatement. Maybe it’s no more than an intense, self-serving kind of eavesdropping, but how else will we gain any sense of the reality of artistic communication?1

Ibonia is one piece among the thousands of items of Madagascar’s folklore. A definition of folklore widely accepted today is by Dan Ben-Amos: artistic communication in small groups. That definition prompts the researcher to pay attention to performance. The approach grew out of the work of the linguistic anthropologist Dell Hymes, under the influence of the sociologist Erving Goffman among others. It has been formulated and developed by Richard Bauman. The object of folkloristic study is people’s cultural practices studied at close range. Goffman, for instance, studying human interactions closely, saw them as if they were dramas, with characters and prearranged scripts. Folklorists like Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett transposed this model into close observation of the telling of a story; she showed the storyteller and audience to be characters in their own drama, which took place beyond the mere words of the storyteller. This was a new matrix, or “paradigm”, for the discipline of folkloristics: performance. Formerly, folktales were studied as texts fixed in writing; now, artists, audiences, and texts were envisioned in a new configuration. Performance folklorists turned upside down the old search for songs and stories as things. Instead of studying texts, they scrutinised moments of social interaction. They stopped trying to explain a particular story as a variant of some hypothetical original. Variation became the norm. What performance theory has to explain is fixity, the absence of variation. Literary studies do not face this problem. Ibonia exists in variant forms; one is translated here — one text.

1 You can also listen to a recitation of my earlier translation of Ibonia at http://xroads.virginia.edu/~public/Ibonia/frames.html.

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0034.02

3. What it is: Texts, Plural1

What is a “text”? A set of words printed on paper. The text translated here is forty-six pages from a book 6 1/2 by 4 1/4 inches, published in Madagascar in 1877.2 The pages have sentences that begin with capital letters and end with periods; it has paragraphs. It also has those long Malagasy names, which are more pronounceable than they look.3 Those long names are constructed out of short elements, each of which means something. Take Andrianampoinimerina, the great king of the Merina ethnic group at the beginning of the nineteenth century. His name is simple: Andriana [prince], am-po [in the heart] in [connecting device], Imerina, the name of his land and people (pronounced Mairn’; the last syllable is likely to be inaudible). Thus he was the Prince in the Heart of the Merina. His memory lingers over the story of

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!