8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

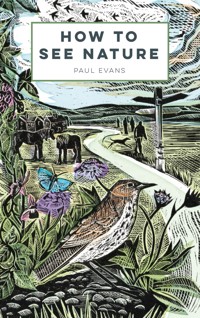

"Pack soup, cheese and a copy of How To See Nature by the Bard of Wenlock Edge and Guardian diarist." John Vidal With a title taken from the 1940 Batsford book, this is nature writing for the modern reader. Evans weaves historical, cultural and literary references into his writing, ranging from TS Eliot to Bridget Riley, from Hieronymus Bosch to Napoleon. It is a book both for those that live in the country and those that don't, but experience nature every day through brownfield edge lands, transport corridors, urban greenspace, industrialised agriculture and fragments of ancient countryside. The essays include the The Weedling Wild, on the wildlife of the wasteland: ragwort, rosebay willowherb, giant hogweed and the cinnabar moth; Gardens of Light, about the creatures to be found under moonlight: pipistrelle bats, lacewings and orb-weaver spider; The Flow, with tales from the riverbank, estuaries and seas, including kingfisher, minnow, otter and heron. The Commons looks at meadowland with a human footprint, with the Adonis blue butterfly, horseshoe vetch, skylark, black knapweed and the six-belted clearwing moth. The author also looks at the wildlife returned to Britain, such as wild boar and polecats, and finds nature in and around landscapes as varied as a domestic garden or a wild moor. The book ends with an alphabetical bestiary, an idiosyncratic selection of British wildlife based on the author's personal encounters.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 247

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

For Maria Nunzia

Contents

Introduction

1. The Garden of Delights

2. Gardens of Light

3. The Weedling Wild

4. The Flow

5. Commons

6. Wild Moors

7. The Greenwood

8. Blight

9. The Returned

10. A Bestiary

Bibliography

Index

CLOUD COVER HIDES GYRN GOCH (‘red horns’ in Welsh), a mountain on the northern edge of the Llyn Peninsula in North Wales, and drizzles on the roof of our van that is parked below a tumble of cottages with the same name as the mountain and on the rabbits nibbling the campsite grass. We walk down to the shingle edging an incoming tide. A small brook passes between the grey, cloudy mountain and the grey, cloudy sea, under cliffs called Aberavon, about 9m (30ft) high. These cliffs are the remains of a raised beach formed at the end of the last Ice Age by sand and shingle dumped from a retreating ice cap when the sea level was much higher. The sand cliffs have been bitten into by storms and the piles of debris on the beach and hanging fence posts above bear witness to recent erosion. Along the cliffs are a scattering of holes, mostly the size made by the circle of thumb and forefinger of two hands together, but some are larger and in shapes that suggest keyholes, letterboxes, slots and squares. I am reminded of an archaeology article describing mysterious holes drilled into cliffs of the River Nile in Sudan, which were discovered to have supported shelters made by people in the Mesolithic period, some 10,000 years ago. The deliberately excavated holes in the Aberavon cliffs may have changed as a result of erosion, but they too have been here for many thousands of years. Suddenly, as if from nowhere, their mining inhabitants come flying home low over the waves and we find ourselves as spectators inside a returning hunting party, a flock or ‘richness’ of sand martins.

Surprised, enchanted and delighted to be surrounded by wild birds going about their own business, and mindful not to interfere or frighten them away, we retreat to a distance where our presence seems not to affect the sand martins that have come back to feed their chicks in the cliff-hole nests. From this vantage point, my wife, Maria, takes photographs and I stand watching the birds, cliffs, sea. I am looking but how do I see these birds and how do I see Nature in general? Having been asked to write this book, this question has become a challenge. How to See Nature, written by the naturalist Frances Pitt (1888–1964), was first published by Batsford in 1940 and it’s a privilege for me to look over her shoulder 70 years later. Through an odd serendipity, it turns out we both come from Shropshire and she lived just along the road from where I live now. When I was a child I loved her photographs for Brook Bond Tea Cards and I used to go to Ludlow Museum specially to see the insect collection she donated. She wrote books about the rescued badgers, otters and squirrels she kept as pets, as well as works on British wild animals and plants made from close observation and dedicated study for a lay audience. The Spectator criticised her natural-history writing for its interruptions by anecdote and digression, something I too am guilty of. In other respects, we are worlds apart. Frances Pitt was a master of fox hounds and vice-president of the British Field Sports Society; her conservatism had its roots in a near-feudal countryside. How to See Nature was written during the upheavals of the Second World War, for evacuees who found themselves far from the city, finding sanctuary from the Blitz and yet cast into the alien environment and culture of the British countryside that many families had lost direct ties with generations ago. Reading her today, Pitt sounds haughtily patronising, but I think she felt a personal responsibility to educate for integration, not only to equip the evacuees with a respect for the wild animals and plants of the countryside that she loved, but also its traditions and values – for her the two were inextricably linked. Her pursuit of natural history was in parts recreational and educational: a lived experience through which she described ‘our’ countryside ordered into road and lane, field and wood, river and stream, common and heath, pond, marsh and moor; and a useful guide for visitors to the countryside inspired by a growing enthusiasm for wildlife. In this way the book formed a bridge to the wider natural-history literature.

How I see Nature in the environmentally anxious early 21st century differs radically from Frances Pitt; I have a very different background, views and access to information; the countryside has changed; so has Nature, so have the people who see it. As I watch the sand martins, these ancient nomads living in an environment as unstable and ever-changing as the sands of the shore, I feel an immense privilege that I can witness their presence and know something about their lives. The sand martins (Riparia riparia) are brownish members of the swallow tribe, they look like house martins, only slightly out of focus. They cross the Sahara from Senegal or Mali to come to Britain each spring to breed here. The females excavate or restore their community nest holes in riverbanks, lakesides and sea cliffs, which must be like tunnelling with a pencil. The males join them and help to create a chamber carpeted with feathers, pieces of grass and inevitable parasites, at the end of a 1m (3¼ft) tunnel for the four or five eggs that are laid. The birds feed their brood on insects caught in flight or else plucked from the strandline. They get their riparian name from inhabiting the water’s edge: a place where the river, lake or sea has deposited material solid enough to burrow into, where it has shaped it into banks and cliffs high enough to be beyond the reach of predators, and next to open water, vegetation and debris for hunting. This riparian edge is in a constant state of flux from wind, rain, storm, flood, waves and human activity – there are many places where sand martin colonies have been constructed in artificial berms or concrete to compensate for those lost to sand extraction. As the cloud lifts from Gyrn Goch, the sand martins seem caffeinated by the bright June sunlight. They pass low over the sea with more flutter and less swoop than house martins and swallows; their rasping, gritty contact calls sound urgent and they suddenly form a circle of around 30 adults and juveniles, clamouring around the cliff’s nest holes, dancing in the air like gnats, while a couple of pairs feed peeping chicks yet to fledge. The birds split up, fly off, come back in ones and twos, in groups of a dozen, full of restless energy – the embodiment of their collective noun. They will leave in October to return to Africa and wintering-ground dramas. Their cliff nests will become temporary roosts for strangers also heading south. Like the people who scraped graffiti into the crumbling Aberavon cliffs – hearts, dates and names – the sand martins have carved their identity into the walls of their ancient unsettled settlement and with it a story of a culture thriving on flux.

I don’t know how much sand-martin life has changed in 10,000 years of migration between West Africa and Britain, or how much each journey of 10,000 miles (16,000km) transforms the individual bird; perhaps we, the inconstant ones, will learn nothing from them. But perhaps they unspool for us a thread of wonder in these otherwise mean-spirited times. During this environmental, social and political turbulence, How to See Nature is written for an audience sophisticated by 70 years of natural history broadcasting on radio and television: an audience anxious about climate change, habitat destruction and species extinctions, turning to Nature for sanctuary, solace, wellbeing and inspiration; perhaps looking back with nostalgia to a version of a world described by Frances Pitt and her contemporaries, such as Henry Williamson and Gavin Maxwell; perhaps turning forwards with a contemporary reshaping of what nature writing might become.

Like the original, this book also wanders, on nature walks of happenstance, a creative hunter-gathering that starts with an encounter of wild things and searches for an ecological literacy, woven from sciences and arts, which attempts to understand and articulate their ‘thingness’, as the poet Colin Simms says. Similarly, Maria’s images are drawn, quite literally, from imprints of memory and experience of things encountered on our wanderings together. This is a kind of psychoecology for a multicultural audience that may or may not have roots in this countryside, but find themselves in a matrix of brownfield edgelands, transport corridors, urban greenspace, industrialised agriculture, suburban expansion, rural development, fragments of ancient countryside and protected landscapes – places that are nevertheless full of Nature to see.

As I finished the previous sentence I received a call from the optician reminding me that I’m late for an eye-test appointment. I return to this paragraph in the knowledge that I have forming cataracts and this brings home to me how fragile the ability to see really is. Seeing is believing? Nature – however we see it and whatever it means to us – is existence, it is what our consciousness is conscious of. How we see is very much influenced by our values and attitudes, moods and emotions, beliefs and curiosity, and that influences how Nature is represented. However, what we see can also change us: often it is the common things we overlook that exert such fascination and wonder when we encounter them and through them we see the world differently. How to See Nature has a sense of urgency because hard-won advances in nature conservation and environmental protection can and are being easily reversed and the Anthropocene – which in itself shows the growing acknowledgement that the human action behind climate change, mass extinction and global environmental turmoil is as defining of this era as geological processes were of the past – has changed how we represent what Nature is.

Despite those anxieties, this is still natural history, still writing about wild lives, animals and plants, where they are, what they do, what we know about their lives and interactions with place, each other and ourselves. Nature shows us that the existence of things is shaped by the relationships between them. However, Western culture is conflicted about Nature. On one hand, we are aware of our biophilia, described by the evolutionary biologist E.O. Wilson as the urge to affiliate with other forms of life, a love of Nature embedded in our DNA. On the other hand, we suffer from ecophobia – the fear of Nature’s answering the consequences of our existence on Earth with violent retribution, from which we have tried to protect ourselves and now realise our retaliation has gone too far.

I intend the perspective of this book to be one of advocacy for what we see – bringing overlooked wildlife into focus as a way of revealing how it matters. Much of the contemporary discussion about how Nature matters has focused on ideas of natural capital and ecosystems services, and although the importance of Nature to human survival and wellbeing is undeniable, seeing Nature as a resource to be exploited and commodified is a denial of its intrinsic value. The kinds of caring we have for Nature – standing up for it through celebration and advocacy and standing in for it through conservation and management – is a cultural project and the natural history I write (my take on nature writing) and Maria’s illustrative drawings form a contemporary narrative, a synthesis of art, science, history, folklore and personal experience. Throughout my life as a gardener, conservationist, writer, broadcaster and academic, I have been inspired by many people and their works have taught me much; my apologies to those I do not properly acknowledge for their support and guidance; at least my mistakes, I am happy to say, are of my own making. Watching the sand martins’ dancing flight around the caring of their young and listening to the communal chatter that articulates their richness, I realise that although we may never understand each other, this writing and drawing is not so much about them as for them.

Little fly

Thy summer’s play,

My thoughtless hand

Has brushed away.

Am not I

A fly like thee?

Or art not thou

A man like me?

For I dance

And drink and sing;

Till some blind hand

Shall brush my wing.

If thought is life

And strength and breath,

And the want

Of thought is death,

Then am I

A happy fly,

If I live,

Or if I die.

WILLIAM BLAKE, ‘The Fly’

A MORNING IN JULY, pegging out washing on the line in my garden and a small fly hovers between me and a pair of underpants. The definition of ‘to hover’, the dictionary says, is ‘to remain aloft, suspended and also to be undecided, to linger solicitously’; a hoverfly is a wasp-like fly that hovers and darts. The hoverfly, 10mm (⅜in) long, its wings a blur, maintains a constant position in the air, deciding; its earnestness suggests questioning. It is small enough to defy gravity, creating a cushion of air for buoyancy while it inspects the pants, recognises colour, senses temperature, humidity, chemical transmission and structure, dabs its pad-like mouthpiece on the fabric and sips, and while it processes all this data the fly allows the sun to flash on the amber bands of its body. Then it is gone.

The fly is Episyrphus balteatus, nicknamed the marmalade hoverfly, because of the striking orange-peel bands on its abdomen. It is one of the most ubiquitous of the Syrphidae flies – true flies because they have a single pair of wings, unlike bees, butterflies and beetles that have two – and commonly called hoverflies because of their ability to stay motionless in the air. Male marmalade hoverflies are territorial and can hover up to 5m (16½ft) above the ground in a shaft of sunlight to attract females and fend off rivals. The adults feed on nectar and they are one of the few flies to be able to break pollen grains to eat them; they are particularly attracted to yellow or white flowers. Hoverflies are anthropophilic – human-loving – in their choice of dwellings, but the more accurate term for such fellow travellers that make a living in the intimate spaces we create around ourselves, is synanthropic. They are close to us.

‘Close,’ is not just a description of proximity, it is also the name of a courtyard, quadrangle, an enclosure within the architecture of a religious or civic building, and the origin of what the Elizabethans called the ‘garden of delights’. Although cultivating plants for culinary, medicinal, cosmetic and fragrance purposes had been central to human dwelling for centuries, the growing of flowers for pleasure and display in intimate spaces of beauty and contemplation became a phenomenon of medieval cathedrals, monasteries, universities and great houses, and was much imitated. Because of this rather aspirational esoteric idea, ‘close’ is often the name given to a cul-de-sac – a suburban house-and-garden idyll. I once lived in a close that was a small cluster of houses with open-plan front gardens built in the 1960s on the footprint of a derelict 18th-century priory – inhabited for a few months in 1809 by the curate Patrick Brontë, long before he was the father of famous daughters – and now called Priory Close. When John Clare wandered the English countryside in 1825 admiring, ‘flat spreading fields checkerd with closes,’ he was describing bright flowering weeds, such as charlock, poppy and cornflower, growing wild but in garden-like patches within the grain crop and, ‘troubling the cornfields with destroying beauty’. This pastoral vision was alien to our 20th century close; its garden plants may not have held the same religious, folkloric or cultural symbolism as they did for the previous inhabitants and their medieval predecessors; the weeds that troubled their cultivation may not have been described as ‘destroying beauty’, but the tensions between what was a garden plant and what was a weed were still very warlike.

Under my current washing line, flower the flat, white, carrot family umbels of ground elder, Aegopodium podagraria. Tradition dictates that ground elder is a Eurasian plant that came to Britain with the Romans. That makes it an archaeophyte, a plant introduced and naturalised here before the 15th century, as were the arable weeds brought by Neolithic farmers thousands of years before John Clare admired them. It is the nature of colonialism and imperialism that occupying cultures bring their synanthropic plants and animals with them, deliberately or by accident. The British certainly have done this with tragic effects throughout the world, introducing plants and animals that have completely changed whole ecosystems. The 17th-century herbalist Nicholas Culpeper included the name ‘Æthiopian Cumin-seed’ in his Complete Herbal, but mainly referred to ground elder as bishop weed: perhaps a satirical common name derived from its use in treating gout, a condition thought to be the result of over-indulgence, or maybe its pestilential reputation as a weed. Culpeper described bishop weed as owned by Venus because it, ‘provokes lust to purpose’; this feels particularly true for the insects visiting the Shakespearean theatre of enchantments of what we now call ground elder flowers.

There’s something Elizabethan about the ashy mining bees that arrive on these flowers. The females are 10mm (⅜in) long, black with a bluish reflection, a ruff of grey hair, a further grey ring around the thorax and a furry white facial mask. The males are smaller, squatter and less strikingly marked. Andrena cineraria is one of 67 species of mining bee in Britain and Ireland. These are hairy little sprites with pollen baskets on their back legs, short tongues and pointed antennae, and are the most effective of pollinators. They excavate nests underground in all kinds of soils. Sometimes they nest in aggregations that can number thousands, although Andrena bees are thought of as solitary rather than social insects. Even though there is no evidence of cooperative worker behaviour, they do appear to be moving together, but more like a dance than a factory. The marmalade hoverflies are individuals, feeding on the lush ground elder and setting their sexual vibrations loose from hovering wings in the surrounding air. Once mated, the females lay white, baroquely sculptural eggs in foliage close to an aphid colony. The hoverfly larva are translucent grubs with a respiratory tube at the back end and mouth hooks at the front with which they pierce their aphid prey and suck out their body contents. A larva may eat 200 aphids in its month-long lifecycle, which is why they’re used as biological pest control in crops. They are also cannibals.

The marmalade hoverfly is Palaearctic and found across Europe, North Africa and North Asia from Britain to Japan, but strangely for such a capable traveller, the species has not found its way to the New World. The British population is often increased by migration. In particularly good hoverfly breeding conditions there can be such a build-up of the population in continental Europe that, with fine weather and a light southerly breeze, huge numbers will begin a northerly migration. Migrations recorded from the Balearic Islands and Sardinia show the hoverfly’s ability to cross the Mediterranean from North Africa. I remember being astonished when I was told the tiny, fragile creature levitating like a cluster of pixels in my backyard may have flown there from the gardens of Marrakesh. However, public empathy with individual lives can be discounted when they become innumerable. Swarms of these wasp-like flies arriving on the British coast, like those in 2004, cause panic headlines and the language of fear and disgust towards such a mass is strikingly similar to that applied to mass migrations of people. The synathropic nature of hoverflies also leads to their destruction: pesticides that kill aphids kill hoverflies. In the kind of irony on which the Anthropocene is built, the eradication of aphids infesting garden plants – an essential prey species for many animals – also eradicates the hoverfly, which is not only an aphid predator but also one of the most prolific pollinators.

A summer generation of marmalade hoverflies may migrate south in the autumn. Many of those that remain, including some larvae, will try to hibernate in ivy or sheds or rot holes in trees. On sunny winter days, they may emerge to warm themselves and dance in sunbeams. There is in hoverflies something of the medieval imagination: creatures hovering over a threshold between the almost supernatural and natural history. Their dangerous wasp disguise conceals sprites employed in the magical work of pollination. Their collective hover-dart-hover behaviour is like the movements of neurons in a Pan-like brain; they exhibit a will and purpose that suggests thought; they question our assumptions. This may be a lot to read into a fly sniffing underpants on a washing line, but isn’t it precisely this vernacular, intimate encounter that creates a sense of community with all life?

Of all the communities we and wildlife find ourselves members of, the garden is one of the most intimate. For many, gardens are defined by ownership, territorial rights and the responsibility for its cultivation, which may be a pleasure, an anxiety or a mixture of both. For others, a garden and its ‘close’ contact with Nature, repose, sanctuary and enclosure may be defined by public access, even if that access is limited by abilities. Gardening is the performance of the movement of Nature into culture. That particular performance is the link between cultivation and civilisation. The result is neither entirely natural nor entirely cultural but a chimera of the two. Human intervention, the kind of care that stands in for natural processes through cultivation, is most directly seen in the design, construction, planting and maintenance of gardens, but it is also present in the historical management of grassland, woodland, heathland and moorland, and more recently in nature conservation management. Benign neglect, the kind of care that stands up for Nature through advocacy and protection, is never truly devoid of human values and preferences, and certainly inseparable from climate change, pollution, habitat destruction and species extinctions. Even in the most manicured gardens, those without ground elder for example, there are synanthropic species that are desired – gardeners’ friends such as robins, bumblebees, hedgehogs and song thrushes – and those which are detested – pests such as slugs, rats, wasps and greenfly. The ecological relationships between these two groups of species may be indifferent to human interests but they will, of course, be directly or indirectly affected by them. Privilege may not afford any degree of protection: the tragic decline of the much-loved hedgehog, and the rapid decline of bees, butterflies, frogs and songbirds, are obvious examples. These favoured species have become collateral damage in a war against garden slugs, aphids, ants, wasps, fungi, moss and the weeds Richard Mabey describes as, ‘plants that find themselves in the wrong culture’; an onslaught that may hardly trouble the populations of the intended victims of such persecution.

All this division into the favoured and the despised appears in startlingly brilliant visual form in the famous triptych by Hieronymus Bosch, painted c.1480–1505, that came to be called The Garden of Earthly Delights. Having been evicted from the original Garden of Eden, the descendants of Adam and Eve in Bosch’s strange garden ecology find themselves in a psychedelic drama of creation that is producing hybrids between people, other animals and plants, and damnation, which is recycling them. The painting’s viewer becomes voyeur, observing Nature, complicit in the pursuit of pleasure through eroticism and torture, in a dream of intoxicating delirium but nevertheless, an ecological garden vision.

In another garden of delights, the head of a decapitated pigeon began to separate further from its body like some ghastly Victorian séance, or at least that is how it looked. A few windfalls lay under the apple tree and I watched them being gnawed by wasps and delicately tapped by peacock butterfly proboscises in the September sunshine. A small clatter of jackdaws settled in the oak tree and a robin sang from the damson. Mist had cleared and that light, which was on the threshold between late summer and autumn, warmed the colours of the garden. My eye was drawn to a bundle of feathers on the lawn, wings folded neatly to its sides, on its back, grey and still: a pigeon. The head was missing; there was just a bloody stump on its neck and no sign of other injuries. This did not look like the work of a peregrine or sparrowhawk – there were no plucked feathers around the body and no opened chest cavity. This looked like the work of a cat, a kill for killing’s sake – an art. However, it didn’t account for the missing head, perhaps eaten, perhaps taken as a trophy. With only a greenwood lyric from the robin, the air was still and warm and soft. The day had a gentleness to it until, returning to the dead pigeon, the head had reappeared. Oddly big, round and brown, it was moving away from the body, and then back onto its neck. I darted around the oak tree to see what was going on – the head was in fact a hedgehog. It was chewing on the pigeon’s neck, backing off, turning around as if in delight, and returning to continue its meal.

Hedgehogs have not been common here for years now and are extinct in many gardens. Despite there being plenty of good hedgehog habitats throughout the UK, half the rural population and one-third of the urban population has disappeared this century. Hedgehogs are generalists, they forage for beetles, caterpillars and earthworms, and relish opportunities for birds’ eggs and carrion. Historically nocturnal creatures of woodland edges, copses, pasture and of course the hedges that act as refuge and connecting byways between them, hedgehogs adapted well to manmade habitats, such as gardens, parks and urban greenspace. Hedgehogs travel surprising distances and require an area of 25–124 acres (10-50ha) to sustain them, regularly walking over 1km (⅔ mile) for a night’s foraging. From November to March, they need safe, warm, dry places to lay up inactively. Their major problems are barriers: roads with heavy traffic, walls and hard fences, paved gardens. Once these barriers fragment hedgehog foraging grounds, the population does not have enough space to sustain itself, individuals can’t breed, and they become vulnerable to predation and being killed by cars or garden machinery. Every year in Britain, hedgehogs are among the five million wild animals injured as a result of their encounters with people. As wildlife and people become increasingly close, the consequences of our actions become more acute.

Gardens account for about one-quarter of the land area in Britain’s towns and cities, and so are important for offsetting some of the effects of climate change through plants absorbing CO2, cooling urban microclimates and supporting wildlife, and for soil absorbing rainwater run-off and reducing flooding. However, urban areas only make up 7–8 per cent of the country, and only about one-quarter of that is garden, and so the impact of gardeners on wildlife is very small compared to that of farmers. The real importance of gardens is that they hold wildlife where people are. Recent studies show that ordinary gardens, where gardeners do everyday gardening things, are great for wildlife.

The marmalade hoverfly, the ashy mining bee and all the other tiny flies are synanthropic members of that community we may think of as the garden of delights, where the strangeness of Nature is far more bizarre than anything dreamt of by Hieronymus Bosch; it’s just a matter of scale. In the poem that opened this chapter, William Blake, with characteristic ecological vision, understood the bond between the almost supernatural actors in the drama of the close.

A STREETLIGHT IN THE LANE enamelled hollies with a sodium glow and sucked the colour from the leaves of other trees, the church bell rang eight or perhaps nine, there was a soughing through the limes. It was late October, almost Halloween. ‘Night comes:’ wrote Nietzsche, ‘O, that I have to be light! That I must thirst for things of night! For solitude!’ Suddenly I felt a tiny sonic boom and the draught of a bat’s wing so close to my ear. It was like a tap on the shoulder, not a shock so much as a greeting, but all the same I was jolted from thoughts about one world into another where solitude is only my failure to see the night filled with unseen lives that collide with mine.

I took the bat wings to belong to a pipistrelle, Pipistrellus pipistrellus: