10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

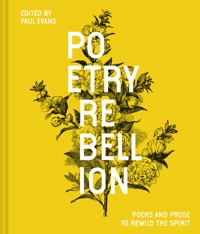

'Galvanises us to notice and care about our glorious natural world, through the words of an army of poets, ancient and modern' – Bel Mooney An anthology of poems to enter the bloodstream and rewild the spirit. As with all life on Earth, the climate emergency, species extinction, ecological disaster, global pandemics, economic collapse, war, genocide and social injustice are all interconnected — how do we face our fears? How do we find the courage to rebel against forces ranged against the Earth? This galvanising collection of poems spans 4,000 years of human history. Ranging from Nikolai Duffy's 'Against Metaphor' and Lord Byron's 'Darkness' to Allen Ginsberg's evocative 'Sunflower Sutra' and Jean 'Binta' Breeze's 'Tweet Tweet'. This book is not just a sanctuary in which to find solace from environmental grief but a manual for psychic resistance in the war against Nature. As Pablo Neruda said, 'Poetry is rebellion.'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 152

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

REWILDING THE REBEL

BIRD

What the birds say

SUN

When the sun shines

MOON

Where to moon goes

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

REWILDING THE REBEL

On the day I begin to write this, Friday 7 February 2020, the television, online news and social media are full of stories about the progress of the coronavirus epidemic towards a pandemic, speculating that it originated in bats, transferred to snakes and first infected people in a market selling wild animals in Wuhan, China; the torrential downpour and floods in eastern Australia that have finally doused bushfires that raged for weeks killing millions of animals and several people following the worst drought in a century; a record temperature of 18°C recorded in western Antarctica as massive ice sheets crack calving bergs into the Southern Ocean; a report predicting the extinction of bumblebees because of temperature extremes, pesticides and the loss of wildflowers to intensive agriculture; and an amber weather warning for the British Isles on an approaching storm likely to cause flooding, severe damage and disruption on Sunday. One day. One day of the warmest year ever recorded, the emergency of wildfires, storms, floods, droughts, rising sea-levels, landslides, people fleeing environmental catastrophe, terrorism, persecution, genocide and the casual extinction of wildlife vies for prominence with political news reduced to celebrity gossip. One day of chickens coming home to roost. On the day I begin to write this I hear birds outside and, as it gets dark, one particular blackbird is singing. ‘Sweet I think the blackbirds warbling …’ writes an unknown 12th-century Irish poet, ‘… the tunes which I hear are music to my soul.’ So, I hold that song as a talisman to slip between the covers of this manual of psychic resistance in the war against Nature.

Anthropocenean rebel! Stand against those forces ranged against the Earth! What does the human spirit need for a revolution, other than data, dream and determination, other than anger and anguish? ‘I want you to act as if the house is on fire, because it is,’ the young climate activist Greta Thunberg told the World Economic Forum at Davos, Switzerland in January 2019. She said something similar to the same gathering the following year, chiding world leaders for their inaction in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence that calls for immediate global action to stop carbon emissions and save millions of species from extinction. ‘Our house is still on fire and you are fuelling the flames,’ she told them.

The origins of anxieties that rage around the climate and extinction emergency have haunted us throughout history. Because human life has always been dangerous – securing food and shelter, protection from predators and disease, anticipating natural disasters, the threat from other people and ourselves – a healthy fear of Nature seems reasonable, if not essential, for survival. There are other fears of Nature: the sort that holds us in awe of thunderstorms and mountains and gives respect to tigers and oak trees, may also be seen as adding to the richness of human life and now motivating action to help Nature. Fears of an asteroid strike, like the one that caused mass extinctions at the end of the Cretaceous, or being attacked or abducted by aliens, come from a fear of Nature at large in the vastness of the Universe in which this tiny planet spins. We have used our ingenuity to secure and expand our niche. In Western society, we have responded to dangerous Nature by trying to conquer, to dominate it. However, it is now blindingly obvious that we have gone too far – too far for people and too far for non-human life. In addition to finding Nature hostile, there is a fear that the environmental damage we have wrought has produced an answering violence. The spectres of atmospheric and oceanic pollution, global heating, species extinction, habitat destruction, novel virus and microbial pathogens and genetically modified organisms have emerged as a consequence of our quest for eternal progress and growth.

These ambitions and their consequences both stem from ecophobia – the fear of Nature’s answering human existence with violence. Science tells us we are changing the climate and ecology into something that is going to wipe us out. It is argued that Nature does not really ‘answer’ anything we do, it merely is the way it is, it is indifferent, and only appears to ‘act’ when we apply a misguided anthropocentrism. Rationalists may say that if we stand back and look at the world objectively we see that we are only projecting our own anxieties onto non-purposive Nature. But that is not our experience; we can no longer shake off our fears about causing climate change and wildlife loss, they have become central to our consciousness of the world.

Back in the 1970s, scientists James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis were developing a theory of life that suggested the Earth and its rocks, oceans, atmosphere and all the living things on it could be seen as an evolving super-organism. This was so radical it could only be published in a counterculture magazine at first. As it developed into more mainstream scientific thought, the hypothesis and its theory, named Gaia after the goddess of the Earth by the novelist William Golding, viewed Earth as a self-regulating system maintaining conditions favourable to contemporary life. The idea captured the public imagination in both scientific and quasi-religious ways that seemed to reconnect the elements of natural magic. Science and poetry are constituent parts of medieval natural magic described by Kitty Scoular as:

… a descriptive term on the borderline between mystical Paracelsan alchemy involving a supposed communion with the hidden forces of nature, and a more modern conception of scientific effort.

Poets from Spenser to Marvell are interested in the ‘variety, enigma, metamorphosis’ of both art and Nature and a possibility beyond truth that lies in ‘the harmony of opposites’, in a veneration of paradox or riddle called Synœciosis. The Gaia metaphor had a similar effect on ecopoetics, ecocriticism and environmental writing that could combine advances in life sciences with creative, imaginative, spiritual literature with a deep desire to save the planet.

Literature shows us that Nature enters consciousness through ways in which we are caught up in the world. As the Sanskrit poet Valmiki wrote, somewhere between the 8th and 2nd centuries:

There is no poetry without compassion

Compassion is a troubled love. We love Nature and we fear it; we feel for wildness and want to control it; we are dependent on Nature and protect ourselves from it; we save species we like and persecute those we don’t. Nature is not simply a construction of consciousness: consciousness is being conscious of something, fear is fear of something. When our consciousness of the natural world is shaped by our fear that it is hostile towards us and capable of destroying us, and our experience of the world is the same, then our way of being in the world and the poetry and philosophy that stems from it is profoundly affected. The literature to come from the current rebellion will produce a radical response to the emergency that provokes radical action; it may have to be very different from that which has already been written but it may draw on some literature included here to inspire or challenge.

Words and the spaces between them can move us and a literature that carries the soul music of Nature has survived longest. The ancient Sumerian poem, The Epic of Gilgamesh, holds a vision of wildness as a place of sacred beauty and purity that resonates today:

They stood marvelling at the forest

Observing the height of the cedars …

They were gazing at the Cedar Mountain, the dwelling place of the gods

The throne-dais of the goddess …

Sweet was its shade, full of delight.

To which William Wordsworth might say:

And so the grandeur of the Forest-tree

Comes not by casting in a formal mould

But from its own divine vitality.

Four thousand years after Gilgamesh, poetry can be a direct connection with Nature and its more-than, other-than, non-human, even preter-super-meta-natural worlds – a spirit-poem entering intravenously, swimming in the bloodstream. Can poetry summon an inner wild in us that walks on land, roots in earth, swims in water, flies through air, drifts in a microbial cloud in community with other lives to rebel against ourselves before it’s all lost? ‘Poetry can repair no loss,’ said John Berger, ‘but it defines the space which separates. And it does this by its continual labour of reassembling what has been scattered.’ My intention in this book is to create a space in the climate and species rebellion to reassemble some feelings, ideas, thoughts, dreams, facts that inspire a standing-up for Nature, and not just those parts of it we like or exploit. This is an idiosyncratic collection, often random, opportunistic, a creative hunter-gathering from literature to support one simple message. Imagine: darkness is falling, the wind begins to roar through trees and rooftops and then, in the teeth of the gale, there’s a moment of clarity – a blackbird sings.

Now a climate emergency has been declared, there is no need to be coy about the pretentions of poetry.

The Hungarian poet Otto Orban said,

I don’t believe that poetry is a care package dropped from a helicopter among those in a bad way. The poem, like a bloodhound, is driven by its instincts after the wounded prey.

The predator-poem is a rewilding: the reintroduction of the literary equivalent of a wolf, lynx, bear, eagle, into ecosystems degraded by the egos of sociopaths, and it searches for signs of vulnerability – guilt and fear. Is it the poem, the poet or the reader that becomes the rebel? It is worth thinking about who or what the rebel for Nature really is. After all, we rebels started this mess.

In the Ancient Greek drama Prometheus Bound, Aeschylus draws on the legend of the Titan, Prometheus, who steals fire from the gods on Mount Olympus and hides it in a hollow willow stem to give to humans so they can escape their wretched servitude. Zeus punishes Prometheus by chaining him to a Scythian cliff where a vulture eats his liver every day in perpetual torture until he’s eventually rescued by Hercules. The tyranny of the gods was defied by the rebel saviour of humankind who was punished and only through suffering achieved wisdom and power. If the gods stand for Nature and the natural order, Prometheus exposes the weakness of omnipotence and his daring, that led to the successful domestication of fire, separated humanity from the rest of life on Earth. He may have got away with it eventually but he was severely punished. This fear of punishment for attempting to control Nature is described by British philosopher Bernard Williams.

… our sense of restraint in the face of nature … will be grounded in a form of fear: a fear not just of the power of nature itself, but what might be called Promethean fear, a fear of taking too lightly or inconsiderately our relations to nature.

We often hide our emotions about what we should properly be afraid of in order to carry on with our lives when we know everything is going to change. This Promethean fear has a powerful resonance in the climate emergency but is hard to express. The understanding (although still resisted in some quarters) that we are responsible for this catastrophe has a long history.

It is thought that Aeschylus presented Prometheus Bound soon after an eruption of Mount Etna (Mungibeddu, in Sicilian) in 479 BCE, one of several during that century. The volcano inhabited by the monster Typhon, imprisoned there by Zeus on the island of Sicily, was the most striking landmark of the Mediterranean world and its eruptions destroyed cities, killed many people and affected the climate. The experience of such a powerful phenomenon in world-shattering action gives fire stolen from angry, violent gods a far greater significance for Aeschylus’ poem; it is a celebration of the rebellion of human reason against superstition told through the crazy clairvoyance of poetry.

Fast forward to western industrial society’s bid for the total dominance of Nature. In Prometheus Unbound by Percy Shelley, inspired by European social revolutions and the Industrial Revolution, a less god-like and, according to Mary Shelley (in ‘Note on Prometheus Unbound’ which follows the lyrical drama), a more Satan-like Prometheus, brings humanity and Nature together in the spirit of social reform and technology in a revolution against the ‘evil’ of the past. A freed Prometheus marries Asia, one of the Oceanides synonymous with Venus or Nature. Prometheus the revolutionary has inadvertently brought about the Anthropocene through technology. The fire that liberated humanity from Nature as the will of gods, replaced it with human Earth system governance. The consequence has been a new form of servitude, to technology.

As I write this on a laptop with access to libraries and the internet in warm, safe surroundings with all the advantages of 21st-century Western industrial, liberal democracy, I can’t help feeling that the floods down the road are partly the result of my privileged lifestyle and partly caused by our collective fear of losing those privileges to a vengeful Nature. Technology, for all its fabulous advantages, is spurred on by ecophobia to create increasingly sophisticated retaliations against Nature. We are where we are. The tale of the rebel Prometheus becomes an anthropocentric creation myth, the sacred stolen fire becomes the pilot light for global heating and climate chaos, a revolution lit in the iron furnaces of Coalbrookdale.

Thy Genius, Coalbrooke, faithless to his charge,

Amid thy woods and vales, thy rocks and streams,

Formed for the Train that haunt poetic dreams,

Naiads, and Nymphs, – now hears the toiling Barge.

And the swart Cyclops ever-clanging forge …

… this rude yell

Drowns the wild woodland song, and breaks the Poet’s spell.

From ‘Sonnet to Coalbrooke Dale’ by Anna Seward.

Perhaps the rebel is now Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus, the monster returning to Nature, driven by fear and rage against his human master. This tortured lonely figure characterizes the ecological grief of the Anthropocene; it has been present, although more or less concealed, for a long time.

… I grieve, when on the darker side

Of this great change I look; and there behold

Such outrage done to Nature as compels

The indignant power to justify herself;

Yea, to avenge her violated rights.

From ‘The Excursion’ by William Wordsworth.

Wordsworth’s grief is caused by the irreversible changes he witnesses in the upheavals in the world around him. The agricultural revolution that occurred mainly between 1750 and 1850 dismantled the system of settled rural communities, sending them to become the blood and bone of the coal-fired industrial revolution, leaving a countryside enclosed by parliamentary laws that favoured landowners, for the towns. Wealth from the transatlantic slave trade and manufacturing-sponsored urban sprawl, woodland clearance, wetland drainage, social dislocation, grubbing up wildflowers, persecuting birds of prey, obliterating ‘wilderness:’ this was seen by the Romantics as an assault on Nature. In a prelude to the alienating pressures we face in the global environmental disaster, Wordsworth had no idea how Nature would ‘avenge her violated rights’ as we are seeing now. His personal experience, observation, intuition and imagination shaped a Romantic nature-mysticism in which he heard ‘voices of two different natures,’ one was Nature’s being that came from the sensory experience of landscapes and the second came from the innermost voice of human being. These two voices are so inextricably linked that the second follows the first, like an echo ‘giving sound … for sound.’ There is, in this collection, an echo quality in poems and feral regions of prose, and there are also pieces which resist the privileged knowledge of the Romantics and the tendency towards nature-worship. However, the connection with Nature through the imagination is a poetic way of revealing something beyond our own self-will that protects us from ‘visions’ and unreasonable weirdness.

Writing in his manuscript notes on Wordsworth, Blake says, ‘Natural Objects always did & now do weaken, deaden and obliterate Imagination in Me’. Blake’s imagination came from a Nature beyond the experienced object. ‘Nature is Imagination,’ said Blake. Link that to Wordsworth’s description of Nature as ‘the indignant power’ compelled to avenge her ‘violated rights,’ and a creative spirit in rebellion is revealed. Those who say rights and vengeance cannot be applied to an indifferent Nature will say Wordsworth must be speaking metaphorically. But this is to underestimate both the power of metaphors and the problem of speaking about Nature without them. Poetic metaphors, where an object is described using the description of another object – an angry sky, a bloody rose, a super-organism – is a way of communicating meaning without having to be taken literally. The imaginative description is received by the reader imaginatively. This connects the images with feelings, attitudes and narratives about them. Through the imagination, the metaphor unites the phenomenal (appearances which constitute experience) with the noumenal (things themselves which constitute reality). Wordsworth claimed his poetic imagination unites phenomenal and noumenal through experience not metaphor in a sort of chemical way. This suggests a physical link between Nature and poet, and poet and reader. The chemistry triggered by objects in Nature is communicated through poetry to engage the same sort of faculty in the reader. This shared experience has the potential for a poetry that, through purposeful and attentive watchfulness, supports a rebellion that sides with Nature. In his poem ‘Turning Point’, Rainer Maria Rilke says,

For looking, you see, has a limit.

And the more looked-at world

wants to be nourished by love

This looking at the world goes back through the traditions of ancient philosophical schools; for example, ancient Greek philosophy arose from speculation about Nature:

But nature flies from the infinite; for the infinite is imperfect, and nature always seeks an end.

From On the Generation of Animals by Aristotle.

The ancient Indian philosophy from contemplation of the spirit:

Ether, fire, water, earth, planets, all creatures, directions, trees and plants, rivers and seas, they are all organs of god’s body. Remembering this a devotee respects all species.

From the Srimad Bhagavatam 2.2.41.

And ancient Chinese philosophy (Taoist and Confucian) from the suffering of the people.

Large rats! Large rats!

Don’t you eat our millet!

We have endured you for three years

But you have no regard for us.

We will leave you,

And go to that happy land!

Happy land! Happy land!

Where we shall be at ease.

Ode 113, Shi Jing (The Book of Odes).

Any shared understanding of Nature will, according to the poet Ted Hughes, depend upon a shared mythology. To Hughes, the natural world and its creatures are universal and timeless: