16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ibidem

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Ukrainian Voices

- Sprache: Englisch

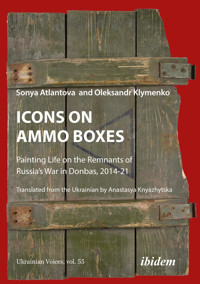

This book has come out of the art project "Icons on Lids of Ammunition Boxes" initiated and led by Sofiia (Sonya) Atlantova and Oleksandr Klymenko. Painted on fragments of empty cartridge containers brought back from the front, the icons are silent witnesses to Russia’s covert war against Ukraine in the Donets Basin in 2014-2021. At the same time, they are testimony to the victory of life over death - not only in symbolic but also in real terms. Since the spring of 2015, the project was a volunteer initiative whose revenues support the Pirogov First Volunteer Mobile Hospital. This unit provided medical assistance to military personnel and civilians in the Anti-Terrorist Operation / Joint Forces Operation zone. The contributors to the book include Volodymyr Rafeyenko, Hennadiy Druzenko, Archimandrite Kyrylo Hovorun, George Weigel, and Zoya Chegusova.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 90

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Sonya Atlantova and Oleksandr Klymenko

Icons on Ammo Boxes

Painting Life on the Remnants of Russia’s War in Donbas, 2014–2021

Translated from the Ukrainian by Anastasya Knyazhytska

Ukrainian Voices

Collected by Andreas Umland

50

Serhii Plokhii

The Man with the Poison Gun

ISBN 978-3-8382-1789-5

51

Vakhtang Kipiani

Ukrainische Dissidenten unter der Sowjetmacht

Im Kampf um Wahrheit und Freiheit

ISBN 978-3-8382-1890-8

52

Dmytro Shestakov

When Businesses Test Hypotheses

A Four-Step Approach to Risk Management for Innovative Startups

With a foreword by Anthony J. Tether

ISBN 978-3-8382-1883-0

53

Larissa Babij

A Kind of Refugee

The Story of an American Who Refused to Leave Ukraine

With a foreword by Vladislav Davidzon

ISBN 978-3-8382-1898-4

54

Julia Davis

In Their Own Words

How Russian Propagandists Reveal Putin’s Intentions

ISBN 978-3-8382-1909-7

The book series “Ukrainian Voices” publishes English- and German-language monographs, edited volumes, document collections, and anthologies of articles authored and composed by Ukrainian politicians, intellectuals, activists, officials, researchers, and diplomats. The series’ aim is to introduce Western and other audiences to Ukrainian explorations, deliberations and interpretations of historic and current, domestic, and international affairs. The purpose of these books is to make non-Ukrainian readers familiar with how some prominent Ukrainians approach, view and assess their country’s development and position in the world. The series was founded, and the volumes are collected by Andreas Umland, Dr. phil. (FU Berlin), Ph. D. (Cambridge), Associate Professor of Politics at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and an Analyst in the Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs.

Sonya Atlantova and Oleksandr Klymenko

Icons on Ammo Boxes

Painting Life on the Remnants of Russia’s War in Donbas, 2014–2021

Translated from the Ukrainian by Anastasya Knyazhytska

Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de.

Dieses Buch wurde mit Unterstützung des Translate Ukraine Translation Program veröffentlicht.This book has been published with the support of the Translate Ukraine Translation Program.

ISBN-13: 978-3-8382-1892-2

© ibidem-Verlag, Stuttgart 2024

Originally published under the title: “Ікони на ящиках з-під набоїв” by Dukh i Litera Publishing House, Kyiv, Ukraine, in 2021.

Alle Rechte vorbehalten

Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Dies gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und elektronische Speicherformen sowie die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Printed in the EU

Icons on Ammo Boxes

National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy

SonyaAtlantova, OleksandrKlymenko

Icons on Ammo Boxes

This publication is dedicated to the “Icons on Ammo Boxes” artistic project completed by Sonia Atlantova and Oleksandr Klymenko. Icons painted on fragments of ammo boxes brought back from the frontlines are silent witnesses to the war in eastern Ukraine and, simultaneously, evidence of the victory of life over death (a real victory, not only a symbolic one). Since the spring of 2015, this project has supported a number of volunteer initiatives dedicated to helping soldiers and civilians who have suffered as a result of Russian aggression.

Icons that were painted on both sides were popular in Eastern Christianity throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. They were intended to deliver a dual message. The same is true of the icons in this book. They are painted on ammo boxes collected from the Ukrainian frontlines. One side still bears the serial numbers of the ammunition the boxes contained, testifying to the war waged by Russia against Ukraine in 2014, and escalated in February of 2022. Most of the icons collected were created between 2014 and 2022, at a time when many people all over the world preferred to ignore the war. And yet it was going on, claiming the lives and health of thousands of Ukrainians.

The other side of the boxes is covered with paintings in the style of ancient Eastern Christian art. The common feature of that style was the idea of transfiguration. Objects in icons look familiar but their portrayal gives them a transcendent quality, having been transfigured into something that exceeds our worldly experience. This side of the icons testifies to peace, which millions of Ukrainians desire more than anything else.

These images demonstrate the transformative power of art. Ammo boxes, the tokens of war, are reused as holy images and tokens of peace. Icons do indeed do transfigure war into peace—at least for those who look at them with faith.

Archimandrite Cyril Hovorun

Director of the Huffington Ecumenical Institute in Los Angeles, CA.

The goals of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine are still not clear after a year and a half of intense hostilities and many war crimes committed by Russian soldiers. When the famous Latin letters that symbolize this invasion are put together, you can easily recognize a slightly deformed Russian word for evil.

The question of why Almighty God, who is the highest Good, allows the existence of evil in our world has occupied a very important place in philosophical and theological discussion, practically since the birth of the Christian system of thought. It is of particular relevance today for Ukrainians, as they are faced with an attack on their country that is morally indefensible and has no other purpose than the destruction of cities and the murder of people.

Alvin Plantinga, a leading American Christian philosopher, gives several reasons for the existence of evil in the world. God cannot contradict his Nature. One should not expect literally everything from God. If God creates a being endowed with free will, we cannot expect that being to be completely immune from an evil choice that is contrary to the nature of its design. The moral value of the freedom of choice outweighs the cost of evil in the world. This explains why our world, created by a wholly good God, is constantly struggling against evil.

People have the tools to distinguish good and evil in their daily lives. Plantinga calls these tools the intuitive axiomatic knowledge of God; for Kant, it is the categorical moral imperative. These factors make us react negatively to manifestations of evil in other people or suffer internally when we commit evil acts.

In the first years of the Russo-Ukrainian war, an external observer might not have had a sense of moral certainty regarding the events taking place in Crimea and Donbas. However, the moral reactions of the people deeply immersed in the Eastern European context (journalists, lawyers, human rights activists and, of course, artists) leave no doubt as to which side of this armed conflict had the moral ground. The Russian invasion of February 24, 2022 stripped away all of the misinformation, tore off all the masks, and eliminated any possible nuances and shades in the interpretation of the events of this war.

One of the very first mature statements on this topic was the brilliant project of the Kyiv-based artists Oleksandr Klymenko and Sonya Atlantova titled “Icons on Ammo Boxes”. The project began its active presence in Ukrainian artistic life at the end of 2014. Since the beginning of 2015, it has extended into European, American, and Canadian spaces. More than a hundred personal exhibitions of Oleksandr and Sonya’s work have been organized around the world, academic articles have been written about the project, documentaries were made, its creators became the heroes of podcasts and news broadcasts.

But the main thing is still the quality of their moral reaction to the war.

Every weapon that fires requires ammo and projectiles. Transporting shells to the front line requires crates. The crates are long wooden boxes lined with iron strips. Shells explode on the horizon, shell casings litter the ground around the gun, crates are strewn across the field or piled up in the corner of a trench. They can be used to start a fire; they can be lined up on the walls of the dugout to keep them warm and less damp. You can make a table or a stool out of them. Crates are what’s left when the work—and in war, “work” is killing the enemy—is done. Piles of ammunition boxes are strewn across Ukrainian landscapes, especially in the east and the south of the country. They lie too far from the place of murder, they are not sufficiently implicated to be guilty, but they nevertheless testify to the violation of the main Christian commandment – “Thou shalt not kill”.

Oleksandr and Sonya collect these boxes, split them apart into separate boards and paint their icons on them.

The iconography of Oleksandr and Sonya is of an innovative nature. Theirs is not simply an image of Eternal Life, but a focus on the distance that separates us from it.

Sonya and Oleksandr paint in the Byzantine tradition. The canonical function of an Orthodox icon—prayer—is completely preserved; however, a conceptual artistic effect emerges in the gap that separates an ordinary board, a piece of cardboard, a canvas and an ammo box. In churches and museum galleries, the icons that appear on the boxes are perceived in a completely different way.

In churches, they are surrounded by the war and seen as emerging from the Ukrainian context—they express the hope of overcoming death, of a new life, not only of Eternal Life, but also of a peaceful life on Earth after the war. Images of saints appear behind translucent war imagery, and they are more powerful, more lasting than this war could ever be.

In an art gallery (outside the Ukrainian context, under the secular spotlights), they are perceived as evidence of evil and a silent criticism of inaction. The background of the icons is different, not a standard blissful piece of the Divine, but a fragment of real life, soaked in smoke, crippled, tortured. The juxtaposition of this background and the easily recognized traditional images of saints brings the viewer into a state of moral confusion.