20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

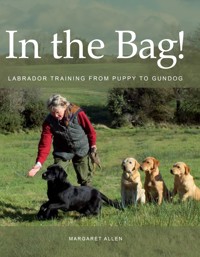

In the Bag! offers a fresh approach to gundog training for beginners and seasoned trainers alike. It contains sound advice on the selection of your Labrador Retriever and valuable information regarding his care and management from puppy to veteran. It gives step-by-step guidance on his training and how to make smooth progress towards the finished article: a Labrador that is a pleasure in the home as well as in the field, and a reliable shooting companion who puts game in the bag. Margaret Allen has been successfully training, trialling, breeding and showing Labradors since 1964. Trying to understand the workings of the canine mind has always held a fascination for Margaret and she believes that in order to train your dog successfully, you should make it your chief objective to find out what makes him tick. In this book, you will learn how your dog thinks, reacts and learns. Armed with this knowledge, training should proceed with a minimum of setbacks. Our working Labrador has been bred for generations to retrieve game - it is in his blood. Through selective breeding, dogs have been produced which are kindly and willing to please. It should not, therefore, be hard work to make him into a Gundog. It should be fun! This book will help you make it so. A fresh approach to gundog training for beginners and seasoned trainers alike, which explains how to train your Labrador so that he is a pleasure to work with and an asset in the field. Contains sound advice on the selection of your Labrador and valuable information on care and management from puppy to veteran. Fully illustrated with 90 colour photographs. Margaret Allen has been successfully training, trialling, breeding and showing Labradors since 1964 and her dogs have been featured in various shooting magazines.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 397

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

In the Bag!

LABRADOR TRAINING FROM PUPPY TO GUNDOG

MARGARET ALLEN

Copyright

First published in 2013 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

© Margaret Allen 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 572 0

Acknowledgements I am sincerely indebted to the many people I have met over the years who have taught me so much about dogs and how they think. I would especially like to thank the following people: John Brentnall, MRCVS, and Terence Girling, MRCVS, for vetting the veterinary bits of this book; Tony Jackson and Sue Orr for their encouragement and proof reading; Paul Quagliana, Hubert Watlington and Sophie Ross Gordon for photographs; Andy Hodder and his crew for their patience and help with photocopying; and Jenny Barber, Shirley Wood, Cheryl Wheeler and Ross Morland, who have helped in so many ways to enable me to get on with writing this book. Above all, I am so very grateful to my family, friends and the many Labradors who were the inspiration for me to start and complete this book.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword by Tony Jackson

Preface

Introduction

1 Look Before You Leap

2 Getting Off to a Good Start

3 Pertinent Care

4 How Dogs Learn

5 Social Graces

6 Preparing for Training

7 About Commands

8 Teaching the Key Commands

9 The Retrieve

10 Putting it All into Practice

11 ‘The Real Thing’

12 Competition

Tailpiece

Glossary

Index

FOREWORD

The art of preparing a gundog for successful work in the field is a skill that requires in the trainer a subtle understanding of animal psychology, combined with the practical application of carefully considered training methods. So often for the amateur or the first-time owner of a young dog hopefully being trained for the shooting field, problems arise due in part to a failure to understand the mentality of the animal or, as is so often the case, an understandable but flawed desire to impose lessons well in advance of the dog’s still juvenile comprehension.

Margaret Allen, whom I have known for many years, is one of that select group of gundog trainers who, having studied the behaviour and mental processes of gundogs, has applied training methods that are based on an understanding of just what it is that makes a dog tick. In the far distant past dogs, whatever their breed or purpose, were trained by ‘breaking’, involving methods that were harsh and today would be considered cruel. However, in the post-war era a new method of training was developed by the late Peter Moxon, a pioneer in the field of dog psychology and understanding, and this has been developed and adopted by subsequent successful trainers.

Many of Margaret’s dogs have won in field trials, working tests and in the show ring, and she and her team of Labradors are greatly in demand for picking-up at local shoots each season. Furthermore, as well as running a successful kennel business, she organizes popular training classes, both for beginners and for more experienced owners.

In this, her first book, Margaret has distilled the knowledge gained over the years, and while she accepts that there are many different ways to teach a dog, there are certain basics that are common to all, and as a result she has developed a method which certainly works for her and the dogs she has had the pleasure of training over the years.

Margaret has greatly helped me train my own Labradors, and I cannot emphasize too highly her skills and her patience, not only with her canine charges but also with their owners! This book is, I sincerely believe, essential reading, not only for the beginner setting out to train his or her first retriever, but also for the more experienced owner.

Tony Jackson Tatworth Somerset 2012

PREFACE

My purpose in writing this book is to give would-be dog trainers an understanding of dog psychology as I perceive it, and to see how it can be used to train and handle your Labrador successfully. I believe that by using the methods described here, you will achieve the best possible result with your dog. You will be, and, I hope, be seen to be, humane. Your dog will respect you and be happy in all his dealings with you. He will understand you and he will give of his best.

This is not a book of political correctness. Dogs have not heard of political correctness. Dogs do not understand political correctness. They cannot understand it and they never will. What they do understand are the rules of the wild pack. Thousands of years and generations of domestication have not changed this. They are happy with their way of life and their perceptions of what is right and wrong. They feel secure and content when the pack guidelines are in place. We are intelligent and adaptable enough to understand this. It is up to us to work out how their mind works. Only when we see things the way they do can we make the connection that leads to a partnership with our dog.

This is not a book for remedial cases. Instances where dogs have got off to a bad start through the harshness, over-indulgence or negligence of their owner is not really within the scope of this treatise. However, I would expect that if my methods are used on a promising dog, albeit a psychologically damaged one, varying degrees of success may be gained.

I believe that breeding plays a great part in the making of a good dog. It will influence many aspects of the animal, including temperament, intelligence, trainability, sagacity, physical soundness, looks and courage. For this reason I have given my opinions on choosing your dog.

I also believe that you are what you eat, and so I have included ideas about feeding dogs that I have found to work well. Along with feeding comes management, so there is a bit about housing, exercise and veterinary matters.

I once asked a man who had done over 80,000 hours of sailing by himself, what he thought was the most important thing in life. ‘Timing,’ he said.

Astonished, I said, ‘But what about love?’

‘Timing takes care of love,’ he replied. ‘Timing takes care of everything.’

How very true I have found this to be, and never more so than in dog training. If you have the timing right, you will make good progress. If you persistently get it wrong, you will make only slow progress, or none at all. Most people are not quick enough to anticipate what their dog is going to do next, but with concentration, effort and practice, this can be improved.

Perfection does not exist in this world, and we cannot all act or react in exactly the right way or at exactly the right moment every time. This does not mean that we shouldn’t aim for a star – we might hit a tall tree!

INTRODUCTION

I was brought up in Bermuda: my father was eighth generation Bermudian, my mother fourth generation. When I was growing up we always had a dog, but I thought that the only things a dog could learn were the whistle that brought him in for supper and the word ‘Gertcha!’ meaning ‘Get out of it!’

In late 1955, when I was eleven, an American lady came to Bermuda and gave lectures on dog training and held a few classes. Immediately I was hooked. I put our ten-year-old cocker spaniel, Rusty, through the exercises day after day. Shortly after that, we emigrated from Bermuda to Edmonton in Western Canada, where my father flew as a bush pilot. Rusty stayed in Bermuda with my grandparents. In Edmonton there was a dog training club. I was over the moon. We soon acquired a dog from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals kennels, a male Husky cross Collie named Skipper. He was a wonderful dog and desperate to learn. He won many competitions for me. When we returned to Bermuda in 1959, he came with us and adjusted well to the new life and climate. In those days dogs were allowed to wander and were seldom neutered. Forty-odd years later you could still see Skipper types around the island!

My mother’s sister was one of the first people to bring Labradors into Bermuda. That was in the early 1960s. As soon as I laid eyes on them, I thought, ‘That’s for me!’ A few years later, when I was married and living in England, my husband gave me a yellow Labrador bitch that we named Christy. I gave her basic training at the local obedience club, and my husband took her rough shooting where she did the job of both spaniel and retriever.

When we decided to breed from her, we were lucky enough to be put in touch with Mrs Audrey Radclyffe, who had the Zelstone Labradors. We used the dog she recommended, and in due course a litter of six delightful pups was born. Mrs Radclyffe said that if I kept a puppy I should bring it to her retriever training classes. But Christy was unregistered, and by now I had realized that I should acquire a registered puppy; so we found good homes for all the pups, and with Mrs Radclyffe’s guidance I bought a yellow bitch named Crystal Clare whom we called Tally. She was by Zelstone Brandy-snap and out of a bitch named Sally Sel.

We attended the classes and both learnt a great deal. Tally was a clever, willing dog and came first in nearly every competition in which she ran. She won her first field trial, which was also my first. Since then I have had many Labradors, golden retrievers, springer spaniels and cockers, but I’m sure that the Labrador will always be my favourite. Many of my dogs have won in working tests, field trials and in the show ring, and I have had a lot of fun and pleasure with them.

In 1984 I was working as a secretary for a very demanding man. One day I woke up and said to myself, ‘I’m quitting this job and never working for anyone else again.’ Of course, one is nearly always working for someone else, even if it’s just for the taxman! I then had to decide what I could do well enough to earn a living. Having trained my own dogs and helped other people with theirs, I thought I would set up a training kennel. If it didn’t work out, it could be turned into a cattery.

It worked out. I have learned a great deal over the years and am still learning. There are hundreds of different types of dog and hundreds of different ways to teach each one of them, but there are certain basics to the method I have developed, and this book is about them.

CHAPTER 1

LOOK BEFORE YOU LEAP

Perhaps you picked up this book because you are thinking about acquiring a working Labrador Retriever. Possibly you already have a Labrador, but in case you haven’t, or are looking for another one, you may find the following helpful.

Turning your hobby into your work is a glad and sorry thing, but that is what I did. My life has revolved around dogs for many years, and when anyone asks me what I do for a living, I say, ‘Anything that’s legal to turn a buck with gundogs!’ But sometimes I feel like David Niven, who said something along the lines of: ‘A writer is someone who wanders about the house in his dressing gown, drinking endless cups of coffee and lost for words.’ There are times when I would rather do almost anything other than train a dog.

Animals are seven days a week, and dogs are no exception. They need frequent, regular attention, which means providing food, water, shelter, exercise, training and control. Knowledge becomes necessary so that you can spot when your dog needs medical attention, and then you may need to devote many hours to his care and rehabilitation. Having adequate time to see to all these things is essential, so before you begin, examine your situation and decide honestly whether you have the time to give a dog its fair share of attention.

WHAT IS A LABRADOR RETRIEVER?

Labradors first appeared in Great Britain in the early part of the nineteenth century, brought in from Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, although probably their earliest forebears originated in Europe. It is interesting to note that the Portuguese cattle dog and the Labrador look remarkably similar to one another.

The Kennel Club breed standard, although open to the interpretation of the reader, gives a good guideline to the appearance and nature of the correct Retriever (Labrador), as they like to call him. However, the breed today is numerically very strong, and thousands of breeders, imagining their ideal Labrador, have all made their contribution. Thus the Labrador Retriever these days comes in a variety of shapes and sizes, although it is extraordinary to note that most Labrador puppies of four and five weeks of age look very much alike, even though they may be from parents of widely differing types.

In appearance my ideal Labrador is a strong, sound, active dog of medium size, with no exaggeration in any point. From the front his limbs should appear straight with good bone, and when viewed from the side, the legs should have good angulation. He should appear to move with an economy of action, smoothly and freely in all paces. He should have a thick, water-resistant coat and a tail like an otter. This tail should wag almost constantly, often thumping his flanks on either side. The permitted colours are black, yellow (which may range from cream to fox-red) and liver. Except for a small spot on the chest, white markings are not allowed. His ears should not be big or hound-like, and his feet should be neatly rounded. He should have a kind, enthusiastic expression and a dark brown eye, and he should look at you honestly as though hoping to discover just what it is that you want him to do. An added bonus is for him to have good pigment – a friend of mine calls this ‘lots of mascara’.

His stamina and athleticism should be outstanding, and his sense of smell exceptionally well developed. Good temperament is paramount: he should be confident, friendly and willing to please. I would want him to be intelligent; not wily, but clever and cooperative. I would want him to be brave, to try hard but not be thoughtless or impetuous. He should not be a good guard dog or be aggressive in any way. A Labrador should have an extremely strong will to retrieve. Throughout his life, a true Labrador is happiest when he has something in his mouth. Of course, food is his favourite thing, but he just loves to carry things about.

WHY DO WE NEED A RETRIEVER?

When shooting game – and this is meant to include duck, pheasant, grouse, rabbit, hare and similar quarry – it is important to recover what is shot. Not only is it important from a wish not to waste good food, but also to get wounded game to hand as quickly as possible for humane dispatch. This is especially important these days when field sports are under keen scrutiny from those who seek to legislate against them.

Crystal Clare – ‘Tally’ – my first registered Labrador and my ideal as regards conformation.

Game often falls out of sight and in inaccessible places. A Labrador with courage and a good nose, and which is capable of being directed to the area where you believe the game lies, will usually find it for you.

WHAT DO WE REQUIRE OF OUR LABRADOR?

When a client brings me a dog to train, he often says, ‘I don’t want a Field Trial Champion, just a useful, obedient shooting dog.’

I then ask if he wants the dog to be steady, walk to heel, come when he is called, take whistle and hand signals, enter water and cover, and retrieve to hand. ‘Oh yes,’ comes the reply.

‘Well, that is just what a Field Trial Champion has to do,’ say I.

A retriever is required to walk to heel off lead, to sit quietly and calmly during drives, or whenever and wherever instructed. He may have to sit patiently for long periods of time. He should be seen but not heard. He should stop on the whistle and take hand signals at a distance. He should hunt where told, confidently and perseveringly. He must retrieve tenderly and to hand with the minimum of delay. It is desirable that he should be happy in water and be a strong swimmer. He should enter thick cover willingly, and be agile and able enough to jump reasonable obstacles.

Labrador puppies love to carry things about.

Why we need a retriever – Labrador bringing a wounded partridge to hand, head up, eye bright.

In addition to all this, there are certain social graces that any gundog should possess. He should be quiet and well behaved in the car, house and kennel, and not go through doorways or get into or out of the car until bidden. He should be agreeable with people and other dogs, and affable about sharing his vehicle with others. He should not take an unhealthy interest in stock or cats.

SETTING ABOUT IT

When Should You Buy?

If possible, it is probably best to acquire your dog early in the year but after the shooting season is over. You will then have all the better weather and more daylight hours to get to know each other and to progress with the training, or in the case of the trained dog, to bond with him and get ready for the coming season.

Labradors typical of the standard – father (black) with sons from different dams.

If you decide on a puppy, it is so much easier to house-train him in the good weather than it is in the winter months. Often the door to the outside can be left open, and even if the puppy doesn’t realize he should go out to do his ‘business’, you can hurry him out when you see the signs.

In the spring and summer you have more daylight in which to go out for training and interesting excursions where he will learn about the country where you live, fences and hedges and how to negotiate them, as well as different types of cover. He can also learn to enjoy water at a time when it is not dangerously turbulent. The water will also be a relatively pleasant temperature, although most dogs seem not to care when it is cold, and it amazes me to see adult dogs leap into icy water to retrieve in the winter.

Which Line?

Make sure that the Labrador you are contemplating acquiring has a pedigree and is registered with The Kennel Club. If the dog turns out to be special you will probably want to breed from it. If you don’t have its pedigree you can’t be sure that the dog you plan to mate it to is not too closely related. In addition you may have difficulty in selling the puppies if there is no pedigree. If a dog is not registered, its progeny will not be registerable, which may also be a stumbling block when selling. Furthermore, many competitive events are open only to registered dogs.

Another point about pedigrees is that you can see how much show blood, if any, there is. Some people like their dogs to have a splash of show blood, whilst to others it is anathema.

The Labrador breed standard was drawn up by people who knew what was required of a good shooting dog. Gundogs must sometimes work for long hours in harsh weather conditions, cold water and dense cover. Certain breed points reflect this. The breed standard requires the dog to have a dense double coat that turns off water and prevents it from penetrating to the skin. It also requires that the dog has substance and strength so that he can withstand long periods waiting in the cold, and then have the stamina for prolonged hunting. The breed points were drawn up for good reasons. I like a dog to be within the standard in appearance as far as is possible, as well as having a talent for work, and the right temperament.

Considering that you may be looking at your dog for the next twelve or fourteen years, his appearance should please you. If it does not, you may come to love him ‘warts and all’, but there is also a chance that your dislike of his appearance will prejudice you against his character, an attitude you may never overcome.

If, in your prospective dog’s immediate pedigree, you see the name of a dog that you know to have a bad fault – say, hard mouth, noisiness, nervousness or aggression – you will tend to be ever on the lookout for the appearance of this fault in your dog, should you purchase it. That is human nature, and it might be best to keep looking.

If you take a puppy from parents and grandparents that were fit for purpose, willing and biddable, healthy and active – a puppy that looks you in the eye and is affectionate, quiet and gentle – you should have a good chance of success in training it. However, not all of us are lucky enough to get to know both parents, let alone the grandparents, and this is where pedigrees come in. If there are a number of Field Trial Champions in a working Labrador’s pedigree in the first two generations, this bodes well. By and large, a Field Trial Champion has proved he has a good nose, a soft mouth, is silent, bold and trainable. If you can find someone who knows particular dogs in a pedigree and can tell you what they were like, especially when they were young, this indeed will be helpful. In addition, if the sire or dam of your puppy has already produced winning progeny, you should feel quite positive about the puppy’s future.

Dog or Bitch?

Bitches are, generally speaking, easier to train than dogs. Most bitches seem better at concentrating. They often have a softer nature and less drive than male dogs. Their main drawback is that they come into season, usually twice a year for three weeks at a time, and during that period they cannot be taken out in public for training or work. It’s a very considerate bitch that comes into season at the end of July and the beginning of February! Some people joke that with a bitch you always have an excuse as to why she is not behaving well: she has just been in season, she is just coming into season, or she is halfway between seasons. However, some male dogs seem to be in season all the year round! They can be more wilful than bitches and more easily distracted. That said, many male dogs are willing, affectionate and gentle, but have a vigour that is very eye-catching and exciting to watch.

I have more enquiries for bitches than for dogs. If a person already has a bitch, he will want to keep things simple and have another. However, if he has a dog, he may think he should now have a bitch and mate them in due course and make his money back! I would caution this person with a saying I heard many years ago, ‘It’s the wise who buy and the fools who breed.’ This is so true. If you breed to keep a pup for yourself, you have only, say, seven to choose from, and fewer than that if you want a particular colour or sex. If you buy, you will have hundreds from which to choose.

As regards making your money back, there can be many expenses, both foreseen and unforeseen. Before a mating takes place, both prospective parents should have the health checks for the breed concerned. There are a number of hereditary conditions which can be passed to the next generation, including joint malformations, heart conditions and eye problems. Most whelpings are normal and natural, but if there are complications, the veterinary bills may eat up any profit.

Another aspect of keeping dogs of both sexes is the problem of dealing with matters when the bitch is in season. You will not want to breed with her at every season and even when you do decide to have her mated, you should not leave the two together the whole time or you will not know which date you should expect her to whelp. A bitch in season will upset a dog, and the other dogs in the neighbourhood, for many days, causing them to fret and howl at all hours. Please do think carefully before embarking on this course.

Choice of sex is a matter of personal preference, and as with colour, it is no good going out to buy a blue hat and coming home with a pink one. If you feel you would be more suited to one than to another, stick to your guns.

Colour

Colour choice is principally a matter of personal preference, but sometimes other factors should be considered. For example, if your shooting is chiefly on the foreshore, it might be best perhaps to choose a yellow dog of a shade that will blend in with the colour of sand and reeds. If your shooting is mainly driven, black might be the best colour. In the shooting field, black Labradors are in the majority, and when someone bursts out, ‘Whose dog is that?!’ it is sometimes possible to keep secret the ownership of the miscreant!

Lotty sleeping.

However, you will seldom successfully override your feelings if you choose a certain colour just because someone else says you should when you know in your heart you prefer another. Believe me, it will affect your attitude to the dog and the results of your training.

AGE OR STAGE OF TRAINING

The Very Young Puppy

I like to have my pups from around seven or eight weeks old. This is when they are starting to learn how to learn. You can’t do advanced training, of course, but it is at this age that a pup’s first deep impressions are received and he will learn the meanings of voice tone and hand movements and what is expected of him in house, car, garden and kennel. If he gets the wrong impressions at this age it may be very difficult to reverse his opinions later on. A further advantage to acquiring a very young puppy is that you will have a good chance of bonding with him. You will be able to assess his character and potential before serious training begins.

When choosing a puppy, I always think of going to see litters of Labrador puppies with Mrs Audrey Radclyffe. We usually went when the pups were between four and seven weeks of age. You cannot tell much before the fourth week. She would watch the puppies for a while and then, one by one, she would pick them up. She would hold each puppy up in turn, facing her, to look at its expression, the size of its head and ears, the colour of its eyes. The head and muzzle should be broad and the ears more or less triangular and smallish, not houndy, and not set on too high or too low. The eyes should be dark and the expression should be kind and steady. In a yellow, she liked to see a good dark pigment of the nose and round the eyes and lips. She would turn the pup to look at the head sideways on, and always liked to see a well defined stop (the differentiation between the level of the muzzle and the top of the head).

Next she would turn its coat back just in front of the flank. She said that if it had a double coat there it would finish with a good coat all over. A short otter-like tail is a must in the Labrador, and the feet should be round and catlike. She would check its teeth to see that it had a scissor bite, i.e. top front incisors just overlapping the lower ones. Then she would let it trot around, noting if it moved sure and straight and whether its toes turned in or out unduly.

Other points she remarked on were whether the puppy looked balanced, in proportion, whether it held its tail too high. Sometimes a puppy will have white toes or a white patch on its chest. ‘Sometimes these disappear,’ she’d say, and often they do. In any case, a working Labrador will often have mud on its toes, and then, what would it matter?

A well bred Labrador pup, eight weeks old, with a lovely confident expression.

When you are choosing a puppy, you should look for all these points and also make sure there is no umbilical hernia. To do this, let the puppy stand and feel under his tummy, or make him sit like Buddha on your lap. A hernia protrudes like half a pea or larger. Some think these hernias are hereditary, but others believe that most are caused by an over-enthusiastic mother at parturition. Probably there needs to be some inherent weakness in that area for the enthusiasm to cause a hernia. Some do close up by themselves; some need surgical attention. Your veterinary surgeon will advise you.

At seven or eight weeks you should be able to detect by feeling if a male puppy has both its testicles descended. If one or both testicles have been retained within the body, this could lead to trouble later in life. Again, a veterinary surgeon can advise you.

Puppy lying on his back on my lap, calm and acquiescent.

Temperament is difficult to assess in a very young puppy, beyond noticing whether he is bold or retiring, quiet or noisy. It is always helpful if you can see one or both parents, particularly the mother. Remember the saying, ‘Breeding will out!’ The temperament of the parents can be an indication of how the pup may eventually develop, but environment plays a very important part too. For example, a highly strung breeder can infect a puppy with the same trait. The most important phase of socialization in a puppy’s life takes place between four and fourteen weeks and it is remarkable how strongly a puppy can be influenced during this period.

Ask the breeder if you may have a low chair to sit on so that you can watch the puppies from a comfortable vantage point. I like to do a couple of little tests on puppies I am considering purchasing, but am careful to ask the breeder if he or she minds. I lay a puppy on its back on my lap to see if it will accept this without struggling. A little struggle is all right, but an absolute refusal to lie happily is not good, as it is supposed to indicate a stubborn, resistant nature. This would not be helpful in later training. Extreme nervousness can show in this little test too. However, puppies change from day to day, and one which seems nervous on Monday may be quite calm and happy on Wednesday. Some breeders may object to you doing something which they may perceive as stressful to their puppies, but this little test can and should be done very gently.

Puppy showing the retrieving instinct: he sees the prize…

At five weeks, it is possible to discover if a puppy has the retrieving instinct. The test for this has to be done with one puppy at a time, so you will have to ask the breeder if you can separate the pup you want to test from the others for a minute or two. Tape up a matchbox which has a few matches in it. Shake this to attract the puppy’s attention, then throw it a little way from him. If he runs out, picks up the box and turns round in his tracks, he has the retrieving instinct. The main thing you want to see is that he turns round when he has picked up the box. Don’t despair if he shows no interest in it, or runs off with it. That may be Monday; on Wednesday he may well do it in ‘copy book’ fashion.

I like to see a nice tail action, one where the tail swishes back and forth, often slapping the ribs on either side with each sweep. It’s a lovely sight. When a dog is working, it is the tail that tells you what the nose is finding out. Style is shown mainly in the tail action. A stylish dog is one which looks purposeful and is a pleasure to watch.

He starts off for it…

The pick-up…

The crucial part: he turns…

On his way back…

A little resistance…

On he comes…

He decides to play…

The delivery.

Eight-month-old Labrador asleep,

The Older Pup

If the pup is not acquired at between seven and twelve weeks, there is something to be said for leaving it until the age of six or eight months, as between the fourth and sixth month the pup will be teething. He will find it difficult to concentrate, and retrieving should be left entirely alone. During this time he will go through many changes, both in personality and in looks. He may be quite the delinquent or exhibit worrying nervousness. His appearance may cause concern, too. His ears may ‘fly’ – stick up at a funny angle – and he may look odd in other ways, and it is not fair to decide at this stage what he will look like later, as these things often correct themselves after teething. At six months he is ready to start more serious training, as he can concentrate for longer periods and is beginning to mature physically.

A youngster of nine months.

A youngster of this age is often available because the owner or breeder has started off running two puppies together. It is easier to have two than one, if you have the facilities. Then at a later date, you can make a more informed choice than you can with a little pup, and part with the one you prefer less. This youngster will effectively be second pick of litter and there may be nothing wrong with it other than perhaps it is a little slower, or bigger or smaller, or carries its tail too high.

Try to choose the animal whose temperament complements, rather than contrasts with, your own character – and perhaps most importantly, find one which looks you in the face.

Over six months, the pup will be developing his own personality and doggy habits and becoming sexually mature. If he has been well socialized – taken about in the car, brought into the house, meeting lots of other people and dogs, and exercised under control, never allowed more than forty yards from the handler – your training will probably be sopped up like water into a sponge. The dog will be delighted to have new interests in his life.

However, if he has been kept in a kennel alone, it is possible that he will be timid and shy, be ignorant of the meanings of voice tone and hand movement, or be extremely boisterous and excitable, with none of the good manners of a ‘home-reared’ puppy. See how he responds to the ‘muzzle-holding technique’ (seeChapter 4) – if he is acquiescent, do not be afraid to proceed; if he resists it vigorously, give him a few moments to get to know you better and try it again, and if he still struggles against you, I would recommend you look at another pup.

If he has been kennelled with another dog and not properly socialized, he will be what I call ‘dog-minded’ as opposed to ‘people-minded’, preferring canine company (and instruction) and missing it noisily for nights on end when he is kennelled alone! This is not a reason to discard the dog out of hand – it just means that some remedial training is needed. Again, apply the muzzle-holding technique and assess his response.

Having Two Puppies at Once

It can be easier in some ways to have two puppies instead of just one. Taking one pup away from his litter-mates to a solitary life does have its down side. The puppy will never have known life without his mother or siblings and, unless he was an only pup, he will always have had company. Of course he will be upset when left alone for the first time, and unless he is given the confidence that you will return, he may go on being upset and very noisy, and perhaps destructive, for some time.

Two pups together, even if they are not from the same litter, will settle happily very quickly. They will encourage each other to eat well, and they will supply warmth and companionship for one another. They can be very rough in play! However, you must treat them as individuals right from the start. Give each of them some one-to-one quality time every day. Teach them the ground rules individually, such as not to be noisy or chew their bed. Feed them in separate bowls, and make sure they do not swap.

Later you need to be self-disciplined: either you part with one when they are no more than six months old, or you start their training, separately. You must take each one out by himself.

The Trained Dog

If you opt for a trained Labrador, be sure to have it demonstrated away from its usual training ground. It should be confident and obedient to its handler. Ascertain beforehand that you will see the dog’s reaction to a shotgun being fired. Take some form of cold game with you – a pheasant, partridge or duck, or a woodcock if you can arrange it. Many dogs are reluctant to pick woodcock.

You should already know what a trained dog should be capable of before going to see a dog demonstrated. If you are unsure, ask a knowledgeable friend to go with you. Ask to see the dog retrieve seen and unseen dummies or game, see if it will jump reasonable obstacles on command, and enter water willingly and bring the retrieve to hand without dropping it to shake. You will be able to learn the handler’s signals and commands, but just to be on the safe side, if you are genuinely interested, go through them with the handler and make notes in order to be sure. You should be able to have several demonstrations so that you really get to know the dog. Ideally, if it is the shooting season, you should be able to see the dog working at a shoot.

Two puppies will play together and keep each other company.

I like purchasers of my trained dogs to come back after two or three weeks for a refresher course to make sure the dog is maintaining his peak level of training, and that the handler is realizing the dog’s full capabilities.

Every dog has its faults, and hopefully you will be honest with yourself and decide if what you see is truly what you want, and also, if the faults you notice are ones which are innate, like whining, and not correctible, or training faults which could with time be rectified.

HEALTH CONCERNS

Health is obviously an important issue where a gundog is concerned, and your Labrador needs to be sound, both mentally and physically. This means of course that, amongst other things, he should be active, athletic, have stamina, good eyesight and a confident demeanour.

The overall impression that a healthy puppy or dog should give is one of cleanness and brightness: clean coat, eyes, ears, nose, teeth, skin, genitals; bright eyes and personality. In addition his feet should be neat, with pads that are not splayed and the nails evenly worn. The teeth should have a close scissor bite in front, the lower incisors closing just behind the upper.

There should be no sign of rash, and no bald patches. Evidence that the dog scratches a lot may show as an area of broken-ended hair behind the shoulders, and this could indicate a number of skin conditions. Gummy eyes can be a very bad sign, and head-shaking can mean mites in the ears. The dog may not shake his head while he is out with his handler and you, because he is so interested in everything else, but a tell-tale sign is that the tips of his ears are bare and sometimes bloody because he has hit them on things when he was shaking his head earlier indoors.

Certain symptoms can mean either a serious chronic problem or an easily rectified one, so it is wise to call in an expert – by which I mean your veterinary surgeon. For example, bare, wet patches could be due simply to an allergy to flea bites. If the dog and his environment are kept free of fleas, the skin will clear and the coat will grow back. However, the cause could be mange or ringworm, both of which are fairly serious problems and not easy to diagnose even with a skin test.

So you see, without an expert opinion you could turn down a very useful dog because you are wary of certain symptoms which might be easily eradicated. Conversely, you could ignore or miss a point which could be the cause of endless future trouble and expense to you.

You should never buy a dog or puppy because you feel sorry for it unless you are happy to be taking on what may be a lifetime of problems.

When you first take your new puppy or dog to the veterinary surgeon, explain the purpose for which he is intended so that he can be checked for all the relevant points.

The overall impression a healthy puppy or dog should give is one of cleanness and brightness.

Nowadays, both parents of any dog or puppy you are considering purchasing should have been tested for the hereditary diseases that occur in the breed. Before deciding to buy, you should have seen the pertinent certificates. Each parent should have a current clear eye certificate. Both parents should have good hip and elbow scores. Dysplasia has been a problem in the Labrador breed for many years. Dysplasia means malformation, not displacement as some people think. No one knows for sure how hip and elbow dysplasia are inherited, but it follows that if you put the best to the best and hope for the best, this is the best you can do. So choosing a puppy from parents with good scores is a good point at which to start (there will be more on this in Chapter 4 under ‘Exercise’). Just recently, researchers have begun work to try to establish a DNA test that will show how hip and elbow dysplasia are inherited.

In my opinion, a score of zero to seven or eight for hips (each side) is acceptable in Labradors, the lower being the better. I believe the breed mean (average) score is 15, being the total of the scores for both hips. Elbows are scored from zero to three, each side, zero being normal. If the dog you are thinking of acquiring is aged over a year, he may have had his eyes checked and his hips and elbows scored. The price will reflect this. A nice natured, well bred, fully trained dog will be in the four-figure price range, so if you are buying such a dog, he certainly should have these certificates.

HOW MUCH SHOULD YOU PAY?

Prices alter with time so I will give you some idea by using a comparison. A well bred Labrador puppy – that is, a puppy with a working pedigree with lots of red ink, meaning Field Trial Champions, in its pedigree – should be priced at about three times the amount of a good class of shooting jacket. This will vary a bit according to the region – puppies from the Home Counties tend to be dearer than ones from the North Country and Scotland.

Puppies that are not Kennel Club registered but have a good working pedigree are usually half the price of registered pups. You should not pay a very high price if the pedigree includes more than one show-bred grandparent.

To my mind, the price of a puppy aged over four months of age should be about £100 per month of life above the puppy price. This rate of increase goes on as time passes and training progresses.

If the dog has won a trial, another rise in price may be added. If he is a young Field Trial Champion, with good hips, elbows and eyes, he should fetch a price that reflects this, bearing in mind his potential as a stud dog. There are now several DNA tests which can be done to indicate whether a dog carries certain hereditary conditions, and you may find that your prospective purchase has had some or all of these tests done. With all this in mind, you must still be truly satisfied with the answer to the question, ‘Why is he for sale?’

Price can be affected by many other factors such as temperament, size, colour, coat quality and looks. It is a good thing to ask for advice from someone you trust – and of course, like anything else, only you can decide what you are prepared to pay.

Free to a Good Home

You will sometimes hear of dogs aged ten to twelve months old being offered ‘free to good home’. Beware: there is usually some problem. The dog may be noisy, aggressive, bad with children or other dogs, an unbeatable escapologist, incurable chewer, thief or carpet wetter. Sometimes, to be fair, dogs advertised in this way are available for genuine reasons, such as a death in the family or the circumstances of the owner, and not due to any fault in the dog.

If you go to see such a dog, take a few biscuits in your pocket. If you like the look of the dog and it is the sex and colour you had decided upon and not overly shy or noisy, try a few tests. Ask someone to go into the next room and burst a blown-up paper bag or slam a big book shut, while you watch the dog’s reactions. If all goes well, try it in the same room. If he tolerates this noise well, there is a good chance that he will not be gun-nervous. Throw a tennis ball, rolled-up sock or leather glove: if he will go and pick it up, good; if he brings it back, so much the better. If he has a decent pedigree and is registered, you will start to be quite interested.

As a further test, ask if you may take the dog for a walk, on lead. The biscuits should help with this. Its reactions to you, other people, other dogs, noises and so on, will tell you a lot about its character. If it seems sensible and pays attention when you speak to it, and if it is friendly and looks at you, I think you may feel confident in taking it on. Only time will tell if it is clean indoors, does not chew or steal, and does not open doors and windows, but these are things which can be got round or rectified.

Occasionally an older, fully trained dog may become available at, say, the age of eight or nine years. He or she may be a retired field trial winner, or she may be a brood bitch which has had her quota of puppies. A nominal price may or may not be charged – often the owner just hopes to find a good retirement home for the dog where he or she will have some shooting work. The drawback with such a dog is that its working life is limited. You will have to be aware that the time is approaching where the dog will have to be paced – they seldom pace themselves – and it will gradually need more care and attention than a young dog.