11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

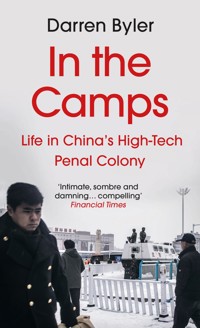

A revelatory account of what is really happening to China's Uyghurs 'Intimate, sombre, and damning... compelling.' Financial Times 'Chilling... Horrifying.' Spectator 'Invaluable.' Telegraph In China's vast northwestern region, more than a million and a half Muslims have vanished into internment camps and associated factories. Based on hours of interviews with camp survivors and workers, thousands of government documents, and over a decade of research, Darren Byler, one of the leading experts on Uyghur society uncovers their plight. Revealing a sprawling network of surveillance technology supplied by firms in both China and the West, Byler shows how the country has created an unprecedented system of Orwellian control. A definitive account of one of the world's gravest human rights violations, In the Camps is also a potent warning against the misuse of technology and big data.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Darren Byler is Assistant Professor of International Studies at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, British Columbia. He is one of the world’s leading experts on Uyghur society and his work has appeared in the Guardian, Foreign Policy, Prospect, as well as many academic journals. He received his PhD in anthropology at the University of Washington.

This edition published by arrangement with Columbia Global Reports.

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Darren Byler, 2022

The moral right of Darren Byler to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-83895-592-2

E-book ISBN: 978-1-83895-593-9

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

Introduction

Chapter OnePre-crime

Chapter TwoPhone Disaster

Chapter ThreeTwo Faced

Chapter FourThe Animals

Chapter FiveThe Unfree

ConclusionBehind Seattle Stands Xinjiang

Acknowledgments

Further Reading

Notes

Introduction

Sometime in mid-2019, a police contractor tapped a young college student from the University of Washington on the shoulder as she walked through a crowded market intersection. The student, Vera Zhou, didn’t notice the tapping at first because she was listening to music through her earbuds as she weaved through the crowd. When she turned around and saw the black uniform of a police assistant, the blood drained from her face even as the music kept playing. Speaking in Chinese, Vera’s native language, the police offi cer motioned her into a nearby People’s Convenience Police Station—one of more than 7,700 such surveillance hubs that now dot the region.

On a monitor in the boxy gray building, she saw her face surrounded by a yellow square. On other screens she saw pedestrians walking through the market, their faces surrounded by green squares. Beside the high definition video still of her face, her personal data appeared in a black text box. It said that she was Hui, a member of a Chinese Muslim group that makes up around 1 million of the population of 15 million Muslims in Northwest China. The alarm had gone off because she had walked beyond the parameters of the policing grid of her neighborhood confinement. As a former detainee in a reeducation camp, she was not officially permitted to travel to other areas of town without explicit permission from both her neighborhood watch unit and the Public Security Bureau. The yellow square around her face on the screen indicated that she had once again been deemed a “pre-criminal” by the digital enclosure system that held Muslims in place. Vera said at that moment she felt as though she could hardly breathe. She remembered that her father had told her, “If they check your ID, you will be detained again. You are not like a normal person anymore. You are now one of ‘those’ people.”

Vera was in Kuitun, a small city of around 285,000 in Tacheng Prefecture, an area that surrounds the wealthy oil city of Karamay, and forms the Chinese border with Kazakhstan. She had been trapped there since 2017 when, in the middle of her junior year as a geography student at the University of Washington (where I was an instructor), she had taken a spur-of-the-moment trip back home to see her boyfriend. Her ordeal began after a night at a movie theater in the regional capital Ürümchi, a city of 3.5 million several hours from her home, when her boyfriend received a call asking him to come to a local police station. At the station, the police told him they needed to question his girlfriend. They said they had discovered some suspicious activity in Vera’s internet usage. She had used a virtual private network, or VPN, in order to access “illegal websites,” such as her university Gmail account. This, they told her later, was a “sign of religious extremism.”

It took some time for what was happening to dawn on Vera. Perhaps since her boyfriend was a non-Muslim from the majority Han group and they did not want him to make a scene, at first the police were quite indirect about what would happen next. They just told her she had to wait in the station. When she asked if she was under arrest, they refused to respond. “Just have a seat,” they told her. By this time she was quite frightened, so she called her father back in her hometown and told him what was happening. Eventually, a police van pulled up to the station. Four officers piled out, three of them middle aged and one just a teenager, around the same age as Vera. On the sleeve of his uniform, it said “assistant police,” the term given for more than ninety thousand private security contractors hired by the police as outsourced labor during the reeducation campaign.

When the officers said they needed to take Vera back to Kuitun to question her, her boyfriend asked quickly if he could drive her back. Maintaining Han-to-Han decorum, the officers said politely that they would need to follow procedures and take her in the van, but that he could follow behind in his car if he liked. She was placed in the back of the van, and once her boyfriend was out of sight, the police shackled her hands behind her back tightly and shoved her roughly into the back seat. The young police contractor, the one who was about the same age as her, was assigned to watch her in the back seat. He sat with one knee splayed to the side at the other end of the bench seat, staring at her blankly, unsmiling, like she was a potential terrorist. She had been put in her place, identified as a Muslim extremist undeserving of civil and human rights.

The region of Xinjiang is located in the northwesternmost corner of China, far into Central Asia and north of another Chinese autonomous region, Tibet. Xinjiang is about the size of Alaska and borders eight nations, from India to Mongolia. Several groups of Central Asian people are indigenous to the region, the largest of which are the Uyghurs, a Turkic Muslim minority of around 12 million, followed by 1.5 million Kazakhs, 200,000 Kyrgyz, and 15,000 Uzbeks. Han Chinese number about 9 million. In fact, Xinjiang, which simply means “New Frontier” in Chinese, is officially the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region—an administrative distinction established by the Chinese state that implied a measure of self-rule for Uyghurs.

The Uyghurs have practiced small-scale irrigated farming for centuries in the desert oases of Central Asia, and with the exception of several periods over the past two thousand years have ruled themselves autonomously along the trade routes of the old Silk Road. In 1755, the Qing Dynasty led by a Manchu government invaded parts of the region. They made it a tenuously controlled provincial level territory in 1884, establishing military outposts in key urban areas. At the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the population of Han- identified inhabitants of the region was around 6 percent, with Uyghurs comprising roughly 80 percent of the population— and nearly all of the population in their ancestral homelands in the southern part of the region.

Prior to 1949, it was unclear whether the region would become an East Turkestan republic within the Soviet Union or whether the imperial boundaries of the Qing Dynasty would turn Uyghur and Kazakh lands into an internal colony of the People’s Republic. However, in 1949, Stalin and Chinese Communist Party leaders agreed that China should “occupy” the region. In the 1950s, the Chinese state moved several million former soldiers into the northern part of the region to work as farmers on military colonies. These settlers, members of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, were pulled into the borderlands through a combination of economic incentives and ideological persuasion. In addition to the Han settlers, nearly a million Chinese-speaking Muslims called Hui, the group Vera was from, have also moved into the region. Today, Uyghurs comprise less than 50 percent of the total population, and the Han now make up more than 40 percent. The region has become the source of around 20 percent of China’s oil and natural gas. It has an even higher percentage of China’s coal reserves, and produces around a quarter of the world’s cotton and tomatoes.

During the early decades of the People’s Republic, the Han settlers largely remained isolated from Uyghurs. Because of the lack of roads and the immense mountain range that separated the Han-occupied lands to the north and Uyghur lands to the south, the vast majority of Uyghurs and Han settlers did not encounter each other in their daily activities. While the Chinese Communist Party did transform the governance structure of the region, in the southern areas Uyghurs maintained leadership positions. The few Han who were stationed in the south adapted to the cultural traditions of the Uyghur world, even as Uyghur religious leaders were banished as part of the purges of the Cultural Revolution.

The relative autonomy the Uyghurs enjoyed in the south of the region began to change in the 1990s as China shifted toward an export-driven market economy. As China became the “factory of the world,” oil, natural gas, and eventually cotton and tomatoes became the pillars of the Xinjiang economy. The search for these commodities drew millions of Han settlers into the Uyghur-majority areas of the region, first to build the resource extraction infrastructure and then supporting industries and service sectors. Over the past three decades, Xinjiang has come to serve as a classic peripheral colony—catering to the needs of the metropoles in Shanghai and Shenzhen. As in other settler colonial projects, the native peoples were largely excluded from the most lucrative aspects of the new economy. When the settler economy precipitated a rise in the cost of living, the expanding urban and resource sectors placed increasing pressure on Uyghur households. While some became tenant farmers in the industrial-scale cotton farms, many were pushed into low-paid migrant work in construction and other sectors.

The shifting economy and political dynamics brought about by the settler migration of the 1990s also precipitated a rise in cycles of protest and violence. For instance, in the township of Barin, near the city of Kashgar, Uyghur farmers armed with hunting rifles and farming tools mounted what is frequently referred to as an “uprising” against the implementation of family planning policies and the preferential treatment of Han settlers who were offered jobs and irrigation rights. While some of the framing of the Uyghur occupation of township government buildings in the incident did center around greater Uyghur self-determination—what the state would describe first as ethnic separatism, and later terrorism—what stood out to the Uyghur intellectual Abduweli Ayup, who was living in the region at the time, was the way the protests were “crushed by the Chinese military.” In a memoir he recalls how “the government followed up with mass arrests.” He remembers the way

eyewitness accounts circulated in my village describing how protesters were loaded like bricks in trucks and hauled away. The police not only took custody of the living but also the bodies of the dead. At the time, all schools were forced to close and everyone was forced to participate in political indoctrination sessions. It is still fresh in my memory, at that time when homes were searched, religious books were burnt, and people were randomly arrested. There were also quiet murmurings among ourselves, knowing that the government was accusing us, the victims of the state’s policies, of being “troublemakers.”

The strict enforcement of settler preferential treatment in the Uyghur majority areas bred significant resentment. Widespread job discrimination, land seizures, and increased government control of religious practice sparked a series of protests and violent crackdowns throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. This rose to a head in 2009, when a Uyghur student protest in response to the lynching of Uyghur workers by Han workers sparked live gunfire from armed police. In response, Uyghurs rioted in the streets of Ürümchi, killing over 130 Han civilians and injuring many more. Over the months that followed, the local authorities introduced a militarized “hard-strike” campaign across the region. This led to the disappearance of several thousand Uyghurs—and more resentment around police brutality and state control.

As scholars Sean Roberts and Gardner Bovingdon have shown, over the past three decades increased forms of control and ethnic discrimination have been the primary causes of increased Uyghur protest and violence directed at state actors. As the discourse of Muslim terrorism entered China in the 2000s, many such incidents were described by state media as “terrorism.” However, it is important to note in many cases the majority of the people killed or hurt in these protests-turned-incidents were Uyghur perpetrators themselves. The “terrorists” were typically unarmed or had improvised weapons and were killed or injured by the automatic weapons of the police.

Eventually, however, some violent incidents did begin to resemble what might be internationally regarded as terrorism. In late 2013 and early 2014, there was a rise of violent attacks carried out by Uyghur civilians that directly targeted Han civilians. Suicide attacks in urban centers such as Beijing, Kunming, and Ürümchi stand out in this regard. These attacks, which utilized knives, vehicles, and explosive devices, are distinctive relative to prior incidents, which were often spontaneous and targeted the police and government authorities rather than civilians. For the first time, Uyghur assailants appeared to be planning coordinated attacks that indiscriminately targeted non-Muslims. Even more troubling, they appeared to be linked not to local political and economic grievances, but instead to resemble the tactics of criminals in Europe and North America who acted on behalf of the emergent Islamic State.

Around this time, Kazakhs and Uyghurs began to participate in social media for the first time. They also became more interested in contemporary Muslim culture and faith traditions from across the Muslim world—such as those inspired by the Tablighi Jamaat, a nonpolitical Sunni piety tradition that has hundreds of thousands of members around the world. The rise of planned attacks and increasing adherence to halal standards among Uyghurs in general, such as abstaining from alcohol, alarmed Han settlers in Xinjiang, who feared a largely abstract, threatening stereotype of Islamic danger.

In addition, during this period, a population of close to ten thousand Uyghurs fled to Turkey via China’s porous border with Myanmar. With the alleged support of the Turkish government, over a thousand of them eventually went on to Syria to fight both ISIS and the Assad regime. As a proportion of the Uyghur population as a whole, this group of foreign fighters was smaller than the number of UK Muslims who also fought in the Syrian Civil War. But in China, the mere presence of Uyghurs in Syria confirmed what authorities viewed as an existential threat to Chinese sovereignty. In echoes of Cultural Revolution–era rhetoric that depicted counterrevolutionaries as vermin, state media began to represent Uyghurs and Kazakhs who were deemed extremists as venomous snakes and disease-carrying insects who needed to be exterminated.

In response to the attacks carried out by several dozen individuals and supported by hundreds more, the rise in pious Islamic practice, and the exodus of Uyghur refugees to Turkey, Chinese state authorities declared the “People’s War on Terror.” However, unlike domestic counter-terrorism campaigns in Europe and North America, the “People’s War” precipitated an extrajudicial mass internment program in defense of the settler society in the Uyghur ancestral lands. Rather than targeting a small number of criminals, the campaign targeted the entire Muslim population of 15 million in Xinjiang. It precipitated a criminalization of Islamic practice and a number of Uyghur and Kazakh cultural traditions. Initially only religious leaders were sent to camps, but by 2017 the war on terror became a program of preventing Uyghurs from being Muslim and, to a certain extent, from being Uyghur or Kazakh.