Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Inductive Scrutinies gathers some of Fritz Senn's major essays of the last ten years. Based principally on Ulysses, they display anew his regard for Joyce's text in all its detail. The selection does not attempt a broad overview of Senn's writing, nor is it organized around a single theme: rather it is meant to show his lifelong interest in the workings of language – its limitations, disruptive energies, its allusive potential within and beyond a single work. In particular it demonstrates continuing concern with the problems of annotation as well as with the reader's pleasurable and active participation. In the editor's words, 'His chosen playground is Joyce as something written, to be scrutinized with dedication. An extraordinary familiarity with the text underlies his response, and his imaginative and nimble explorations always start with and return to Joyce's word.'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 544

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

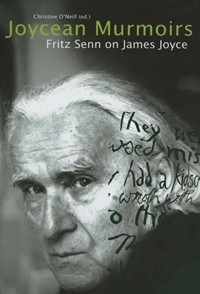

INDUCTIVE SCRUTINIES

FOCUS ON JOYCE

Fritz Senn

edited by Christine O’Neill

CONTENTS

EDITOR’S ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Eleven years after the publication of Joyce’s Dislocutions: Essays ofReadingasTranslation (John Paul Riquelme [ed.] [Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press 1984]) I approached Fritz Senn with the idea of publishing a new collection of his essays. The enthusiasm of The Lilliput Press for the project provided the necessary encouragement.

The essays, for the most part on Ulysses, have already been published with the exception of ‘“All Kinds of Words Changing Colour”: Lexical Clashes in “Eumaeus”’. There are only a few minor changes, and no attempt has been made to avoid partial overlap for where the same passages are discussed, they are under scrutiny from different angles. I wish to thank the following for permission to reprint: Heyward Ehrlich, editor of LightRays:JamesJoyceandModernism, for ‘Remodelling Homer’; Morris Beja of Ohio State University Press for ‘Joyce the Verb’; Thomas F. Staley of the JoyceStudiesAnnual for ‘In Quest of a nisusformativusJoyceanus’; Associated University Presses for ‘Joycean Provections’; Robert Spoo of the JamesJoyceQuarterly for ‘In Classical Idiom: Anthologiaintertextualis’; Mary Snell-Hornby, editor of TranslationandLexicography:PapersreadattheEURALEXColloquium1987, for ‘Beyond the Lexicographer’s Reach: Literary Overdetermination’; Christine van Boheemen for ‘Linguistic Dissatisfaction at the Wake’, ‘Protean Inglossabilities: “To No End Gathered”’, and ‘Anagnostic Probes’.

The editorial work was carried out in Dublin and Zürich. I wish to thank Antony Farrell and Mari-aymone Djeribi of Lilliput for their support throughout, and the Friends of the Zürich James Joyce Foundation for a generous grant. I am grateful to Mary Power and Katie Wales for editorial advice, and to Ruth Frehner and Ursula Zeller of the Zürich James Joyce Foundation for reliable back-up. Tim O’Neill was essential for help and encouragement. My best thanks go to Fritz Senn for giving me the opportunity to undertake the project and helping me to see it through. This collection is a tribute to his dedication to Joyce and the Zürich James Joyce Foundation, now in its eleventh year.

CHRISTINE O’NEILL

Dublin,May1995

INTRODUCTORY SCRUTINIES: FOCUS ON SENN

The present volume collects some of Fritz Senn’s major essays of the last ten years, mainly on Ulysses. They display anew his regard for Joyce’s text in all its detail. The selection does not attempt a broad overview of Senn’s writing nor is it organized around a single theme; rather it is meant to show his lifelong interest in the workings of language, its limitations, disruptive energies, its allusive potential within and beyond a single work, in particular his ongoing concern with the problems of annotation as well as the reader’s pleasurable and active participation. His chosen playground is Joyce as something written, to be scrutinized with dedication. An extraordinary familiarity with the text underlies his response, and his imaginative and nimble explorations always start with and return to Joyce’s word. Not that this excludes forays to non-Joycean areas; classical references are particularly frequent. His essays also convey a sense of a mind at work, developing, exemplifying. Senn probes with agility and argues and extrapolates sceptically. Not for him interpretative certainty or the monolithic argument drawn out to book-length. Hence a volume of inductive scrutinies.

In his introduction to Fritz Senn’s Joyce’sDislocutions:EssaysonReadingasTranslation (1984), John Paul Riquelme, the editor, looks at Senn’s particular advantage as a non-native speaker in reading and explicating Joyce. He stresses the fine awareness of linguistic irregularities and disruptions in a reader who takes nothing for granted. As the essays demonstrate, such a sensibility turns reading into an act of translation and criticism into a running commentary on the text. The view of Senn as foreign commentator helps one understand his critical preoccupations.

For the last decade Fritz Senn has been directing the Zürich James Joyce Foundation. This institute, the most comprehensive Joyce library in Europe, consists largely of his former private collection of work editions, translations, criticism, background material and realia. A favourite haunt of many Joyce scholars, it provides ideal research facilities and is a welcoming place where ideas are exchanged. At the regular workshops Senn’s chairing is invariably unpolemical, stimulating and friendly.

As this collection coincides with the tenth anniversary of the Zürich James Joyce Foundation and with thirty-five years of Senn’s published writings on Joyce, it seemed appropriate to invite Joyce scholars to comment on his status. The spectrum of views which follows should be of interest to novice and seasoned Joyceans alike. However, to present a balanced picture, I also asked Senn to talk about himself, and this interview, characteristically informal, concludes the introduction.

In a letter to some twenty-five Joyce scholars of varying age, nationality and critical inclination, I wrote of my endeavour to ‘situate Fritz among other Joyceans concerning his particular interests, strengths and critical preoccupations, but also with regard to his limitations or, if you wish, blind spots’, and asked for frank and descriptive rather than evaluative comment. I mentioned that Senn knew of the letter and condoned it. As it turned out, those who answered were pleased to have been asked for comment even if some felt daunted by the task. Despite my promptings I received no replies with strong negative criticism.

There is general agreement on the nature of his work. It is considered unique in Joyce criticism. This is to do both with the nature of his contributions and his personality. His feeling for Joyce is based on an affinity of temperaments, and some consider him the best reader Joyce ever had. He seems to read Joyce in the writer’s own spirit. Without ever dominating the text by his intellect, Senn puts all his knowledge and critical ability at its service. He does not curtail Joyce’s dynamics. His readings are invariably lively, clear and original, and even the most familiar passages still yield surprises under his scrutiny. The attention he brings to bear on textual detail is painstaking, and his interest in period trivia comes close to Joyce’s own.

As for the nature of Senn’s contributions, they are of particular value to readers interested in philology and stylistics. Ever alert to the strangeness and comedy of Joyce’s language as well as to the experience of reading it, he responds with a text very much his own. His style is inimitable, incisive, witty and lucid, however complex the issues he discusses. Also, Senn is one of those rare scholars who do not need to keep citing theorists. This is partly because he is unusually independent in his thinking, so much so that often he can only express himself with the help of newly coined terms. Yet many Joyceans feel that Senn’s ideas are in tune with some of the most important ‘theoretical’ writing of the last few decades, especially Derrida’s. They see his writing parallel and, more so, anticipate currently fashionable theory. Some Joycean scholars think him unwilling to acknowledge, others unable to see, how much his approach to literature shares with the best examples of post-structuralism; one scholar put it that he ‘obstinately denies affinity and understanding’ (with or of Derrida). Senn’s own view of his relation to theory finds expression in the interview and in the preface. Maybe this is the place to mention Senn’s mischievous, quizzical personality and his sly and sometimes punishing sense of humour.

Fritz Senn is known to encourage and develop up-and-coming Joyceans. He shows great patience with them, but less so with renowned scholars. At the same time, he is unusually open to the ideas of anybody interested in Joyce.

Senn is thought by many to be a gifted teacher. He manages to make Joyce’s works approachable and fresh without sacrificing their complexity and strange inventiveness. He considers questions more fruitful than answers. It is his familiarity with the texts that enables him to be continually surprised by them. However, he is least patient with dullness and scholars lacking textual knowledge or clarity.

Senn’s classical knowledge is remarkable, likewise his extraordinary feeling for the connections between Ulysses and its Homeric precursor. Far from referring to the Odyssey as a simple grid for Ulysses, he never tires of searching into Joyce’s unique translation and rewriting of Homer and exploring the interaction between the two texts. Joyce through Senn, and Senn through Joyce do agitate the Odyssey.

Several scholars referred to Senn as an authority on FinnegansWake. He is considered a pioneer in its exegesis, and the enormous importance of AWakeNewslitter in the history of the work’s reception is undisputed; Senn was co-founder and co-editor (he insists that Clive Hart did most of the work). For one thing, the Newslitter helped towards establishing reasonable and verifiable standards for interpretation. That he has detached himself from the Wake in latter years (see the last essay in this collection) seems almost completely ironical to some scholars, who feel it is only now that the consequences of his original endeavours are coming to fruition.

A few individual remarks from the thumbnail sketches, assembled without connection or comment, may add up to a impressionistic collage. His ‘gadfly’ presence at conferences has been mentioned, or how when struck by certain ideas he seizes on them with a ‘tenacious fixation’. His insistence on looking at the text directly with the invariable result of seeing what was otherwise neglected marks him, according to one scholar, as ‘singularly smart’. There was the pithy remark that everything he says or writes could be placed ‘under the banner of common sense operating at expert level’. It was felt that Senn’s recognition ‘honoriscausa’ from the University of Zürich was a ‘tribute from all scholars’, and that he is ‘sui generis and indispensable’. Lastly, many a Joycean would share in the wish that closed one letter: ‘Long may he write as he does.’

Thanks are due to Derek Attridge, Morris Beja, Bernard Benstock, Christine van Boheemen, Vincent Deane, Michael Gillespie, Hugh Kenner, Terence Killeen, Margot Norris, Marilyn Reizbaum, Joe Schork, Jacques Aubert and Katie Wales for their frank and incisive observations.

INTERVIEW WITH FRITZ SENN, MAY 1994

HowdoyouviewyourdevelopmentasaJoyceanoverthepast thirty-fiveyears?

‘Development’ suggests a maturing process or an ascent towards some commendable peak. Come to think of it, by hindsight, I wonder if in the long run—and the run has been long—I developed sufficiently (I’m talking Joyce here). Somehow it seems I’ve been doing the same thing all over all along, with of course stupendous advances in sophistication and refinement that anyone could spot with a magnifying glass. Probably I should have changed more. Overall, I have been trying to figure out, often in close-up—Joyce, after all, offered extended close-ups, Ulysses for one—just how language works, what it can achieve, and what it fails to put across. So in some way I am a case of arrested development, and my interests now resemble those of thirty years ago, with a few illusions gone. It is not the worst kind of development to be arrested in, but a limitation nevertheless. I should hasten to add that my fellow Joyceans have never, as far as I could make out, held this against me. In fact I have been treated extremely well and graded all too leniently. On the whole, we are a tolerant and appreciative lot, if anything too agreeable to each other. Self-styled ‘Joyce Wars’ are an exception. Of course, not to sound too modest, I also know that I have an interest shared by few, and fewer in recent trends, that in language. Not Language. I could provide you with a handy rule of thumb to find out who does not care about language.

Andwillyou?

No.

Couldyousayafewwordsaboutshapinginfluences,orthelackofthem?

I’ve had an advantage early on. As an autodidact—I still sometimes flaunt an amateur status or, rather, I watch myself creeping back into it in escalating disillusionment—I have not been conditioned by any academic school I know of. Wrong, of course. As Gerty MacDowell or, for that matter Stephen Dedalus, could teach us, we are all shaped by something, and most of all by what we do not even perceive. But I mean since I was generally not on an academic payroll—just exceptionally as ‘visiting professor’ in the US and, over the years, in association with the University of Zürich—I could take up what suited me. I picked what I found congenial and was never obliged to string along with any trend. Call this ‘eclectic’, it sounds better.

Aretherecriticalactivitiesyourefrainfrom?

‘Refrain’ implies a policy or strategy. I simply avoid, like most animals, what I cannot cope with. I was never really trained in Joyce criticism or disciplined to enlarge my skills outside a narrow chosen field. So you’ll never catch me criticizing Foucault’s views on Husserl in their bearing on Martha Clifford’s male gaze within a commodity culture (post-colonially en-gendered). In fact I ran away from the language of German philosophy into the relative safety of the Wake, which one is justified in not understanding, and this after many years, and which even not understanding is fun. As you can observe now, the language of philosophy has been infiltrating big, via France and the US. So much for safety. Others, at any rate, are much more competent at metaphysics than I am, so I gave up on it. You see that a student nowadays cannot afford such defection. So I never have really kept abreast, certainly not to what is apotheosized as, say, ‘Literaturwissenschaft’ in Germany. Scares me stiff. Distinct from my colleagues—perhaps I have no right to call them that after all—I am ill at ease in cryptic abstraction, and I am not, as everyone else seems to become, a critic of Culture. In fact I am not a critic, but at heart a commentator, a scholiast, a provider of footnotes. And a prequoter. (Somewhere I must have explained that term.)

Couldallthisbeconnectedwithpossibleblindspots?

Most spots are blind. If you want to know about me, as you seem to—sense of duty, no doubt—I am characterized, as far as introspection goes, but outsiders see it much better, by a few oddities that it took me a long time to become aware of. One, as said just before, is uneasiness with transcendencies. I am too dumb—try to find a euphemism—for all theory. Period. ‘Theory’ for me is everything that excludes an audience not elaborately trained in it. That explains some of my groanings and bleatings, even outbreaks of frustrated anger. It has led to continuous self-doubts. It’s not that I ‘disagree’ with theories, I wish, rather, I knew what they are so that I could engage in arguments about them. As I say somewhere else, I have been waiting fairly long that something worth knowing from all these occupations would seep through. Irrespective of the value of theories, which is for others to judge, they have the lasting scorched-earth side-effect. Words, once innocent, cannot be used any longer. It happened to ‘desire’, ‘gaze’, ‘space’ and now even to ‘other’ as a noun. Every time we (still) have to use ‘absence’ or ‘silence’ a little bit of self-respect crumbles off. ‘Cyclops’ teaches us that we never see our own blinkers, so the second quirk took me much longer to put a finger on, as it seemed too natural to me. That is, when a topic is announced, say for a workshop or panel, I instinctively turn to the text and see what I can come up with that approaches relevance. Such naïveté I never questioned until it dawned on me gradually that, in decent academic procedure, a detour is required, some (often arcane) sanctioning by authority, even if the authorities adduced seem to be categoricallydenying any sort of authority. And then there is another peculiarity of which I am not even ashamed. Whenever I knocked out a footnote or an article I always took it for granted that—apart from adding to the store of perennial universal knowledge—my subjective enjoyment of the text should be passed on. The pleasure principle. I am surprised right now that this has to be said at all. New potential readers are helped, I believe, if they get a sense that Joyce may be worth reading, that it adds to their lives, though for the life of me I could not say what. I always thought basics are more important than all superstructures above them. Maybe not, then let’s say they are more basic. Basics for me meant learning to read—continuing present tense. Once you get some rudiments of that you may well graduate to metaphysics, and I am always a little nonplussed to find that rudiments actually can be skipped so cavalierly. But then I also admit that what most of us, in the old text-oriented camp, are doing can be atrociously stolid and uninspiring.

OverseveraldecadesofJoycecriticism,whatshiftsoffocusdoyouobserve,andhowdoyourelatetothem?

Out of interest and necessity I did survey the scene early on, in my budding enthusiasm more than now. You know, there were times when we were actually looking forward to a new study of Joyce. And made sure to read it. When I set out—as a reader entirely, until James Atherton prodded me to do something on Zürich allusions in FW, which pushed me over the edge into the arena—I saw two main directions: one was traditional and in many ways ‘positivistic’, with the focus on biography, source studies, quotations, comparisons, influences, background: few Joyceans then were familiar with Dublin. And then there were the interpreters who offered, as often as not, symbolic readings, some inspiring, some mechanical. Myth had a big run, and all the more so because one didn’t have to explain quite what it was nor how it worked, but it gave one’s pronouncements vibrating universal scope. Irony came to be all the rage. I soon drifted to the Wake. Some of us, belonging to the early explorers of what was largely uncharted, were trying to find meaning. We thought we knew what finding meaning was in those days. And we needed contact, especially me, who was dabbling along in complete isolation. There was a bunch of early Wake annotators, Adaline Glasheen, the most brilliant correspondent of them all, Atherton, Hodgart. Thornton Wilder travelled with a copy of FW, its margins brimful of minute pencil marks. One day I got a letter with some enquiries from a student in Cambridge by name of Clive Hart; another emerging student had finished a rare dissertation on FW and was surprised to get a letter from across the Atlantic: Bernard Benstock. So we soon developed an unofficial network, based on curiosity and capricious rapture, which no doubt later was infused by politicking and career strategies. One of the results are the Joyce Symposia that now, ironically, seem to have become the Establishment Olympics. If you knew how scared we were at our first attempt in 1967 in a Dublin that was at best indifferent, at its wittiest scathingly sarcastic. Naturally the scene expanded, approaches diversified in all directions. At some point it was hard, and soon impossible, to keep track. Joyce scholars outside of the United States became less negligible. And correctives to the mainstream were needed, especially to those articles that seemed oblivious of fiction being fiction, confected, forgeries, verbal phantasms, affairs of permutated letters. Or ‘Text’! That term has had such a career that it now has become advisable to look around for new metaphors. Change was overdue. Along came ‘Structuralism’, which surfaced, for me at any rate, in the person of Jacques Aubert in 1972. This may show the secluded life I had been leading. Officially Structuralism raised its disquieting head with a flurry of new droppable names at the fourth Joyce Symposium in Dublin in 1973. This was alongside the primeval feminist panel, inaugurated by Ruth Bauerle. Well, I for one never got the hang of the pioneering novelties, though, by one of fate’s little tricks, I remember that a talk of mine at a Ulysses reunion in Tulsa 1972 was labelled a ‘structuralist reading’. So perhaps our minds are, naturaliter, structuralist—or whatever comes along, for comparable suspicions have been levelled at me later on. As it turned out, and to show how behind the times some of us were, we found that in the middle of the stream all of this—in particular Lacan, whose teachings Aubert had perpetuated of his own accord in the early seventies—had been changed or relabelled Poststructuralism, in collusion, for all I can tell, with its sibling, Postmodernism. We entered a great phase of sign posts. Well, all of this has had a great impact on the Joycean scene, and after some efforts I even gave up trying to have it explained to me what the impact was. But of course all the exciting, new, overdue departures were where the action was, and certainlynot in the perpetual recirculation that these theories tried to break away from.

Youarewithoutdoubtapassionate Joycean;doyouhaveallergies?

Passion, funny, that has sometimes been applied to me. I saw my preoccupation with Joyce more as a distraction, a survival technique. Yes, I do have allergies where I overreact. In the old times there were those dreary moralistic judgments. Professors of English seemed to look down from Olympian heights on the poor people in Joyce’s Dublin and they were arrogantly sticking labels like ‘paralysis’ and ‘simony’ on characters that they found wanting, morally or spiritually. Critics judged life or human behaviour and I never quite figured out how they should be better qualified than others. In those days fertility and sterility were freely dished out at the drop of a symbol. Well, perhaps young Joyce proclaiming that well-touted ‘moral history of my country’ was taken up seriously. I resolved not to hold that one against the author. Some critics even spotted Christian miracles. To show my obtundity, I have never been able to see Buck Mulligan or Boylan as particulary wicked or despicable, and I always felt great affinity for Gerty MacDowell. To me Joyce’s moral impact always appeared to be empathy with our shortcomings—our shortcomings, not just Farrington’s or Eveline’s, or, as I tried to put it, sympathy with varieties of human failure. The main books are epics of failure: we don’t reach our goals and, above all: ‘Nilhumanumamealienumputo.’ Wholly subjective, of course, such views, not to be proved, but then you asked. Yes, and another overall allergy: the propensity of even battle-proved professionals to get up at a conference and to read—brilliantly or platitudinously, as the case may be—preformulated text from a typescript. The result is aptly called a ‘paper’, named after the most insignificant part of the whole production, the material on which thoughts become fixed. You know that I have been leading a losing fight against the recital of papers, and you can still annoy me very easily by inviting me to read one.

Doyousometimesfeelyourpointshavebeenmissed?

To be sure. Our points are always missed. It’s what Joyce writes about. So one should be immune. But it is sometimes odd to find oneself quoted, out of context naturally, or rather within a wholly distorting new one. Or else a statement long forgotten or somethingso trivial as hardly worthy of mention surfaces out of well-deserved oblivion. That’s all in a day’s work, I suppose, or the way of the word. But on occasion one is a bit piqued. I may find one of my views dug up as though I had framed it with an implied ‘nothing but’, the kind of formula I not only religiously avoid but go to great lengths to refute the very notion of. What stuck most dishearteningly is that I once in an essay on ‘Nausicaa’ steered pointedly clear of the once-common condemnations of Bloom’s masturbation and briefly summarized them in order to take a more profitable turn—and then in a fine book on Joyce’s sexuality I discover myself as a spokesman of precisely those censorious voices I had distanced myself from. Of course that showed I had not expressed myself as clearly as had been my purpose. Incidentally, you’d hardly imagine in how many ways a simple name like Senn (common in Switzerland) can be misspelled: Sin, Sen, Zen, Zimm, Senft, etc., all follow in the trail of M’Intosh, L. Boom and several others. ‘Eumaeus’, I find more and more, is true to life.

Haveyouanycommentontheappearanceforthethirdtimeofaneditedcollectionofyouressays?

If for the third time—or fourth, depending on what you include—someone else, in this case you, goes to the trouble of assembling scattered articles into one volume, then it is a safe bet that this triple-edited author will never ‘write a book’. Psychoanalysis might look into this block and dredge up fascinating unsavoury diagnoses, probably fear of some sort. It’s not that I have not toyed with the idea. Once I thought of investigating what Joyce does with time, ‘NarraTime’ it would have been called, if it had ever got beyond an accumulation of electronic notes. Or I thought I would do something on the chapter relations in Ulysses. Well, to paraphrase L. Boom: ‘Still an idea behind it. But nothing doing.’ I just don’t have that wide horizon, or the illusion that any impetus could profitably expand to book length without becoming both tedious and laboured and, somewhere along the way, plain wrong. Sour grapes, but then anything systematized to any great extent stumbles into the kind of dogmatism that Joyce’s works seem to counteract, especially the Wake with its built-in scepticism. Therefore I am scrutinizing minutiae, but I try to extrapolate and to generalize tentatively and with visible signals of reservation. In my better moments I flatter myself, not for very long, that some incentive has been given.

Couldyouelaborateonyourpreoccupationwithprocesses, dynamisms,kinetics,urges,excesses,forwhichyouhavetoinventyourowncriticaltermssuchas provection, anagnosis, dislocution, allotropy?

It was just my interest. I didn’t know that I was doing so until it dawned on me and I felt—wrongly in part, no doubt—that many others concentrated on what there is in Joyce’s texts and did not seem alerted to what happens. Our minds are skilled categorizing things, and things are easier to pigeonhole than elusive processes, such as, in extreme, FinnegansWake. Joyce texts seemed alive, in motion, verbs rather than nouns, kinetic in another sense than what assistant-professor Dedalus had in mind in his fame- and pompous lecture. Textual energies serve as antidotes to the inertia of reification. That’s why I was getting annoyed, and have publicized, not always kindly, my impatience with static annotation that tends to freeze the text and to stop further inquiry. But then again, since Joyce brings many such truisms to unexpected light, I have hardly ever done anything that I did not also think obvious. Everyone could have seen the same processes at work. Some corrective commonplaces of years ago have become mainstream clichéd pomposities. What once was necessary to point out may have turned into new dogma. I do not know whether I was amused or irritated when once I had used a talk merely to illustrate that Joyceans, against all the evidence under our eyes, can still be so certain about their own precious findings without any trace of doubt. Two years later at another conference it appeared, paradoxically, as though Uncertainty itself had become infallible dogma, so much so that one participant referred to ‘that uncertainty we are all looking for’. As though we had to make an effort to discover what is so conspicuous all the time. So I see myself rather tritely on the old beaten, maybe outdated, humanist track. Joyce never invented, but only illustrated anew, the old Socratic caveat, ‘Are you quite sure?’ Some of us still are. Quite sure. It took me years to experience fully the import of one early aside in Ulysses, attributed to Haines: ‘— I don’t know, I’m sure.’

INSTEAD OF A PREFACE: THE CREED OF NAÏVETÉ

Thefollowingletterarosefromanarticleinthe‘JamesJoyceBroadsheet’whichcontainedareferencetoastraylettertotheeditorIhadcomposed.Thepersonsinvolveddonotmatter,butitoccurredtomethatextractsfrommystatementsofthetimemightclarifyinadvancewhatup-to-datereaderswillnotfindinthefollowingprobes,andwhy.Joycewasverygoodatcircumscribinglimitations:thoseof Eveline,JamesDuffy,Boylan,Gerty,Stephen,butalsothoseofstylesandmodes—heseemstoinclude,inparticular,ourrarehaphazardinsights.Ithinkweshouldthereforestateourown,rightfromtheoutset,ourweakspots,theblinderswehave.

(…) I would also like to clarify a few things that are on my mind. First of all I have no judgement on Deconstruction, or Theory, as such. I know it is there, it is important, is taken up, means a lot to many. I simply do not understand it, and even trying to do so may set me back for months of depressive paralysis and resignation. I have nothing to say on your subject in general. There are some very good friends whose work and minds I highly respect and who have been into these theories. So I deduce there must be something there that is of value. But it does not reach me. So I always ask just one thing: What then is it that you can do, with your approach/theory/ philosophy, that we fogeys cannot?—what questions, what answers, perhaps. And, please, demonstrate it to me in concrete textual detail. Now for reasons beyond me this is not to be done; the rules of the union do not seem to allow that. OK, then that has to be accepted. But, when, as I tried to make very clear in my letter, on rare occasions, they (the ‘theorists’) do stoop to a bit of text and when, very very rarely, it becomes clear what they mean, then (and only then) I always felt—at least until now—we could have achieved the same results or have reached similar conclusions in the traditional way. My remarks refer to these exceptional cases—are more or less in the conditional.

When the prophet descends to the market-place then he has to be judged by the market-place. Things may be different on Olympus; but there, though it gets crowded more and more, I do not belong.

My view is not that ‘a disseminative reading is not really differ ent’—I do not know what disseminative readings really are nor what they disseminate. I wish I could see them as disseminative. But when something is applied to a bit of text then I can agree or disagree.

My concern is lucidity, nothing else. The one thing I require of book, talk, panel—to be able to follow. Perhaps lucidity is not compatible with certain approaches. But once you address a large audience, say at a Symposium carrying the label ‘Joyce’, a tacit assumption is that you want to put something across. I find the unwillingness of theorists to do this—on the level of the uninitiated—depressing. Now this may be my problem, up to a psychological point it is. At the same time, believe me, I would like to learn, to learn from them as well.

Of course there is the impression that ‘they’ (perhaps all theories) have relatively little (visible) interest in Joyce, they put the focus somewhere else. Nothing wrong with that; scholarship is open, must remain so, no holds barred, there must be a wide scope, new angles; and we all have a right to our own brand of curiosity. No-one should be forced to focus on Joyce. At our Joyce conferences, however, a minimum of such focus or interest seems to be implied by the name, and when current fashions take over a bit much, disproportionally much, then a feeling of waste becomes painful. Now for all I know, ‘they’ may have a great deal of interest in Joyce, and great insights too—and I am sure some of their enthusiasm is very genuine and exciting—but somehow the insights do not penetrate outside the hermetic circle. So I am still waiting.

However, there is a bias that you noted. My implication of a difference in interest is simply based on a notion that, if theorists have something of interest to say, to say on Joyce, then in the long run something of this would rub off, something would get around—so that it might even reach the likes of me, the obtuse, pedestrian, naïve simple-minded readers. It may happen tomorrow. It hasn’t yet. But within decades of so much Joyce scholarship sailing under all those French (mainly) flags, don’t you think a few results might be expected by those without the temple? Or, to put it differently, if ‘By their fruits ye shall know them’, as the chap said, is a valid rule, then some fruits should be forthcoming at some stage—fruits, mind you, not treatises on metadendrology, though this may be a fascinating subject in itself.

Perhaps it is an insult to expect something as commonplace as results from on high. Theories, I know, are not vending machines. This too would have to be accepted, but it would have to be announced first, and announced plainly and unmistakably. In the meantime, having heard and seen and watched from afar the mountains in protracted and much-published labour, we Philistines are still waiting for the mouse to emerge. Barking up, no doubt, the wrong mountain.

And again: I do not distinguish between simply those interested in Joyce’s works and the ‘voguish [etc.] Larridians’, but those among them (as distinct from the Masters) who are in demonstrable fact voguish, epigonal, dilutive and flag-waving: I assume their legion gets on your nerves even more than mine. In fact I think that those concerned with theories should safeguard against the bandwagon syndrome. There are a few Joyceans I could name (and won’t) by whose taking up a theory you know it has now been debased into a fashion. I also mean the name-droppers, the authoritarian quoters. The Joyce world is free to accommodate them (at any rate, they would be a nuisance at any period). And another thing you should be concerned about, I mean you as a FideiDefensor: Why are (and here I am really inclined to generalize) all theorists, from inspired top to epigonal bottom of the barrel, such poor translators? Why do they not (want to?) communicate? At least some of them, by the law of probability, might be expected to try.

You will have noticed that none of my remarks refer to Critical Theory, Deconstruction, or any of the philosophies concerned. I am not qualified, I do not know about these things (most of my friends still think I am being coyly or facetiously modest when I confess that I am too dumb for theories). My remarks refer solely to the performances in Joycean contexts that I have witnessed. (I am not sure the Masters would always have been pleased with those performances.)

I realize full well that looking at a bit of text and trying to figure out what it may mean (which delimits my own narrow, philological garden), is not sufficient. We need to go beyond, widening our contexts and horizons, by all means. Some scholars, Joyceans, naturally want to aim higher. And we certainly depend—for new input—on those who are able to lift their noses from the close reading and who concern themselves with the Larger Issues. It’s not that I am simply speaking up for the old-fashioned traditionalists (of which I am one by constitution), all those plodders who produce glosses, sources, influences, biographical, symbolic, or (Joyce help us!) moralizing readings, etc., etc. I know all about their tedium. Or rather, as I also tried to express in my letter, we get some very dull, uninspired scholars in all camps; the majority of us are just not very brilliant, no matter what we do.

You see now why I do not belong to the academic world and have always remained an amateur. I want to increase my knowledge, understanding, and pleasure in the text, works, language—and beyond that, inductively, into all areas: language, psychology, history, etc. all the way to Culture, Metaphysics, and perhaps even Life. Everything that helps me in this is (subjectively) good, everything that does not help me I cannot assimilate, it runs off my back. My complaint is restricted to our own gatherings. There it has happened a little bit too often that someone, instead of telling us something about Joyce, got up and proclaimed, in substance, some name in current use. I supposed for a considerable time it would be possible to say something about both areas, something that is meaningful in our own. Maybe this has happened, and you can tell me where it has.

You realize that according to my reiterations here it would be enough to produce one single insight, one single gloss, one single reading that is both new and clear, to make the general gist of my complaints null and void. Just a single one. The demand may be unfair. But then, and that would be OK too, it would have to be explained (as to a child) once and for all why theories (or a particular system) cannot be concerned with such trifling side issues.

Now in all of this, as I keep repeating, there is a large portion of subjective pathology. But I do compare experiences; I do talk to others, also young people, students. So I am not quite alone. It took me a long time to figure out a simple truth that does not apply to me alone, but, at least, to a scared minority. There are many reasons for theories: (wo)man is the theorizing animal, our curiosity—a metaphysical bent—new horizons, points of view, attitudes, exploration, our bases, ideologies have to be challenged, and all the rest. I know. But most current literary theories in their looming bulk also have one drawback, one that is wholly irrelevant to Research and Scholarship, but does have an impact nevertheless when they become obligatory or endemic: they increase human misery. And here I am not merely airing my own hang-ups, but thinking of students that have confessed to me how they feel when, apart from all the obscurity and challenges of Joyce’s texts, they have to grapple with further obscure abstractions on top. I myself can get by, more or less, at least some of the time (I even get insincere compliments from the other camp), but many of those young and timid, lacking self-confidence, cannot. Perhaps the whole repetitive gist and appeal to you all up there is simply: For heaven’s sake try to be clear and lucid on occasion—or even helpful. There is, after all, also a Little Chandler in Joyce’s works, and a Bloom and a Molly.

February1988

* * *

Such was that letter (now abbreviated and slightly modified) of years ago in which I now discover a faint trace of misplaced optimism. I have no intention of calling up an implied spectre of earlier, glorious times now gone—they never existed. Yet the old philological game, never too popular anyhow, has played itself out; it has certainly come to grief over FinnegansWake (see the piece on Dissatisfaction). It has to make room for all the inspired Others who have won the day, those with wide outlooks and depth, scanning nothing less than the horizon of all Culture, and History.

On the other hand one may be forgiven for holding on to a conviction that Joyce is not such a limited writer that he can only be accessed through contemporary metaphysics. The approach taken throughout is of the Illegitimate Shortcut, of going (with all one’s biases and preconceptions, wrong ideologies and what have you) straight to what appears on the page and trying to puzzle out, very provisionally, the mysterious dynamics of those signs, and to guess at meanings and how they come about. It looked like an interesting exercise in its day and may in fact never die out entirely.

JOYCE THE VERB

in the muddlewasthesounddance (FW 378.29)

I begin with a few sample quotations. These are not for your applause or disagreement, but merely in order to probe and appreciate the semantic variety of the one recurrent word, ‘Joyce’:

Joyce was born in 1882—The Tenth International James Joyce Symposium—Joyce was conscious of his control of English and other languages—This book enters Joyce’s life to reflect his complex, incessant joining of event and composition—From his late adolescence onward, James Joyce intended to be a writer—The sacred is at the heart of Joyce’s writing experience—Joyce insists that man’s will is free, that it can be exercised for good or evil, and that the state of the world’s affairs will vary with the quality of leadership—What does Joyce assert or imply about guilt in Ulysses?—Joyce is disgusted by sexual impulses regarded as normal by most standards of behaviour—Joyce’s mind was at all times engaged in the search for truth—When I first met Joyce in 1901 or 1902, he was beginning to emerge as a Dublin ‘character’—Joyce was too scrupulous a writer to tolerate even minor flaws—Joyce spent his life playing parts, and his works swarm with shadow selves—Joyce’s laughter is free and spontaneous—Joyce wrote not for literature, but for personal revenge—Jim Joyce devoted a whole big novel to the day on which I was seduced—Joyce is writing the book of himself.

There needn’t be any contradiction at all, but meanings differ. It is equally true to say ‘Joyce has been dead for forty-five years’, as to claim ‘Joyce is alive.’ ‘Joyce’ does not equal ‘Joyce’: What is the statue of Joyce in the Fluntern cemetery of Zürich a statue of? Joyce Symposia, among other events, give partial answers.

The question will not be pursued here. It is the name, noun, nomen, ‘Joyce’, that interests us. It epiphanizes a bewildering diversity of meanings, semantic differences that we, the professional differentiators, do not always notice. The diversity at first sight would appear odd, for names, of all words, ought to distinguish persons; it is their function. They often fulfill it. Reading Joyce (you see, we use the name but don’t mean the person), we might learn about the chanciness of easy identification by nominal labels. Insofar as names are for things, the distinctions work reasonably well. But even so, undoubtedly concrete objects like keys or bowls are not just objects. Keys can open or lock, they are for entering, for excluding, for taking along, for forgetting, for being handed over, for ruling or usurping. Bowls are for carrying (or ‘bearing’), for holding aloft, for shaving, for mocking, they may play the role of chalices at times, and chalices, we have read, may contain wine, or be empty, even ‘idle’, can be broken—or not broken. Such objects, many at the beginning of Ulysses, are for actions, or acting.

Those privileged and, usually, capitalized nouns, however, that have no general referent, the names, serve to keep persons apart for convenient identification. Not unconditionally. You may remember Kitty O’Shea, the one that, Molly says, had a ‘magnificent head of hair down to her waist tossing it back’, and who lived ‘in Grantham street’ (U 18.478). This name then has different reverberations for a reader who (a) knows no Irish history at all, for one who (b) knows a little, and for one who (c) is an expert. It is the knowledge we bring to bear on the name that makes the difference. But even a historian well versed in late nineteenth-century Irish affairs will have to match Molly’s acquaintance, at least for a fleeting instant, against the bad woman ‘who brought Parnell low’, and then decide against an attractive identification. A name translates into knowing, or not knowing. Walter W. Skeat, the English etymologist, makes one of his infrequent negative remarks in the entry on ‘Name’: this word and its Latin cousin nomen are ‘not allied to “know”.’ The two word families are not related, but in practice they work together. The cognates of ‘know’, however, are allied to that one item in the much-quoted triad of strange words at the opening of ‘The Sisters’— ‘gnomon’ (D 9). And this gnomon merely sounds like, but has nothing to do with, Latin nomen, though it happens to be one; the similarity is deceptive and ominous.

The platitudinous pay-off of all this, predictably, is that in identifying we are doing something. All the meanings we concede, knowingly or not, to the term ‘Joyce’ imply some kind of activity. At one extreme the word does duty for a life lived in various cities in the course of almost sixty years; at the other possible ends of the scales it suggests writing, thinking, creating, developing, intending—you name it, and you name it appropriately by verbs. Such verbs also become our panels and lectures and animated disputes. Aware of such dynamisms, some of us have quite independently—when this could still be done with impunity and even self-respect—coined the verb rejoyce or rejoycing.

Even the adjective ‘Joycean’ predominantly means not some stable quality, but rather what Joyce actively provoked and what, conspiratorially, we now do in turn and with considerable energy. None of us may be able to define ‘Joycean’ adequately, but we vaguely sense that it connotes some heterogeneous, but characteristic hyperactivity: words seem to be charged, or else we readers charge the words, somehow, it seems, beyond the norm. Ask anyone in Dublin.

To simplify the foregoing, names, for all their accepted substantiality, soon dissolve into doings, into the verbs from which grammar distinguishes them, at least in Indo-European languages. If at this point you nod facile assent and find, rightly, that I am kicking outdated horses and dismiss notions long out of date—or that someone has already put all this into a system of trendy abstractions—then just look at most of our practical applications. Look at how we, commentators or critics, seem often at pains to re-reify all that elusive work in progress, to freeze it into solid theses, symbols, parallels, discourses, or even ‘puns’, things that we can categorize and administer.

Joyce might be the antidote. His works release the processes out of the nouns, nouns which are so much easier to handle than events or doings. The pioneering etymologists who drew up a set of language origins of common Indo-European ancestry, usually tabulated roots that tended to be verbs of action. Joyce seems to descend to such origins. The roots of the two cultures that he revived bear this out as well.

Dominenamine (U 6.595)

Once the God of the Old Testament had spoken light into being and approved of it, he went on and ‘called the light Day’ (Gen. 1:4). Genesis follows the birth of the world right away with the birth of the first noun. Somehow Joyce celebrated this pristine noun thus generated in his secondary creation; we in turn now also use ‘Bloomsday’. God then, soon after, shaped a being that was called ‘man’. His personal name emerges first in the midst of another naming process:

The Lord brought [the beasts of the field] unto Adam, to see what he would call them [and we find an almost Joycean sort of divine curiosity]: and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof. (Gen. 2:19)

Calling (‘quod vocavit’, as the Vulgate has it) precedes the name (‘ipsum est nomen eius’). And Adam, the first-named, started to give names to the animals around him; he also decided that the outgrowth of his rib shall

be called Woman, because she was taken out of man. (Gen. 2:23)

Adam is the object of naming and becomes its prolific active subject right away. Creator and first creature are both protonomastic, not only the first namers around, but also those who start with naming before almost anything else we find on the record. The names, of course, allow the record to be written. Conversely, the calling of names in the upward direction, towards the divinity, might be tabooed. Potent naming and ineffability go together. Naming is potent, and so is knowing or uttering a name. Adam’s powerful prerogative is shared by writers of fiction.

The Hellenic version differs in conception and idiom, but the Greek epics, oldest witnesses, work the naming of some of their heroes into their tales. In the most famous digression in literature, Odysseus is named in what appears the most arbitrary and whimsical way, in almost Saussurean fashion, and yet the random signifier becomes potently ominous. Since grandfather Autolykos passing by at the birth happened to be ‘odyssamenos’, the child was called, ‘eponymously’, ‘Odysseus’. The participle form ‘odyssamenos’ is either ‘made angry’ or else ‘making angry’ (reductive philologists, like their Joycean counterparts, may disagree); it suggests a man connected with wrath or odium, and it came to signify both a wrath inflicted and a wrath suffered.

So naming has been around from the beginning. Joyce, the Namer, is well within a tradition that allowed for metamorphotic scope. A central name ‘Bloom’ coincides with a common noun, offshoot of a verb, bhlo (cf. florere, blühen, etc.), but a noun for some live process, blossoming, growing, changing, withering, radiating, smelling, all astir with poetical echoes. When Miss Marion Tweedy adopts it by patriarchal custom through marriage, her rivals inevitably joke: ‘youre looking blooming’ (U 18.843). The verbal connection offers an appropriate flourish for the central onomastic cluster. Names, necessary social designations, arise out of, and turn again into, verbal energies, long before FinnegansWake.

Joyce the Writer set off with almost no names, as suits lyrical poetry. ChamberMusic can do, practically, without them. But not prose narrative; Dubliners has a wide range of appellative possibilities: full-fledged name (Ignatius Gallaher), last name only (Lenehan, Farrington), or first name alone (Maria, Lily), with or without a honorific (Mr James Duffy, Mr Duffy, but Corley), with a sprinkling of eponymous flourishes (Hoppy Holohan, Little Chandler). In all this diversity, the first three stories do not divulge what the protagonist narrator is (or the three narrators are) called. The technique of gnomonic elision or silence extends to names: one that is pointedly withheld seems to assume even more power than those known. But from now on there are names in abundance: a whole critical study can be devoted to them.1 Some were taken from Joyce’s own background, some appropriated abroad, from printed sources, or invented, many synthesized. Perhaps the most outstanding example of imaginative naming is ‘Stephen Dedalus’, in defiance of almost all realistic plausibility: it represents a soaring, mythical, high-water mark of portentous naming—its growing significance is thematized in APortrait. But more and more, especially from Ulysses onwards, personal names are shown to be problematic. In the final work, they have lost their discriminative graphic edges, and identification becomes our readers’ necessity and pastime more than an overt concern of the work. It would be difficult to talk about the Wake if we had no nominal handles for its profusion. But its nominal blurrings would not be accepted by immigration officers on our passports, and our computers too would be obstinately uncooperative.

So we might roughly sketch a curve rising from pristine, lyrical anonymity to mythological ostentation, and down again towards a terminal pseudonymous fuzziness. But such a simplification would obscure the innate perplexity in between, the inherent riddling nature of names. But throughout, I submit, the naming is at least as important as the individual names used. Joyce’s methods are often genetic. Ironically, the first occurrence of ‘name’ in Dubliners is connected, not with something coming into being, but with the loss of the vital force. The reverberating term ‘paralysis’ is introduced as sounding strangely like the name of some maleficent and sinful being (D 9), attached to a mortal activity, an action which means the disablementfrom acting. Appropriately then, the priest’s name is not communicated to us until it is read on his death notice, when paralysis has done its fascinatingly ‘deadly work’.

Before any one person in APortrait has been identified, the process of naming is put before us. The opening tale within a tale features a ‘nicens little boy named baby tuckoo’—named. Named by others, from outside, imposed from above. It will happen to the main character soon ‘— O, Stephen will apologize’, and whether guided by the precedent of Genesis or simply by empirical common sense, we take the name on trust ever after. Stephen hardly thinks about it until others remark on its strangeness. Once the naming of ‘baby tuckoo’ has taken place, incidentally, the fairy story is discontinued right away, as though it had now, the secret being out, lost all further interest.

When real names do take over, we are not always helped. One fully labelled ‘Betty Byrne’ is never heard of again. Soon we will come across a ‘Michael Davitt’, but few readers nowadays could tell, offhand, untutored, who he is; for all we know at first, it might be a member of the family. (If you disagree, you are simply substituting scholarly annotation for average knowledge.) One early conspicuous name, ‘Dante’, is flickeringly misleading. Most of us, semi-erudite, will have to discard the nominal association of an Italian poet who will be named, towards the end of the book. But the person called Dante early on will later translate itself unexplained into ‘Mrs Riordan’. In life and in literature, we usually come to terms with such confusion. Joyce exploits the confusions inherent in naming. Coincidences and convergences will later facilitate the mechanistics of FinnegansWake.

When Stephen’s family name, commented on all along, is linked to its mythological origin and import, it translates into such actions as flying, soaring, falling, creating and, later on, estheticizing, or forging. Most of these active revelations follow close upon the mocking evocation of a Greek participle, ‘BousStephanoumenos’, in which Stephen’s Christian, very Christian, name is made to derive not from crown, the object, but from a verb for crowning. The fourth chapter, where all this happens, moves from a static beginning of almost lifeless order and institutional clusters to an ecstasy of motion.

It would be idle to repeat how deceptively the first names come on in Ulysses, ‘Buck’ and ‘Kinch’. Commentators who claim that ‘Chrysostomos’ in the earliest non-normative, one-word, sentence, ‘is’ the name of some specific saint disregard the inherent process of naming through characterization, a process which then may very well lead to one particular saint. Stephen silently bestows an appellation on the usurper2 who towers over him, one that fittingly singles out his most prominent organ. In some way this is Stephen’s tacit hellenized tit for Mulligan’s loudly voiced tat, ‘Kinch’. Ulysses starts naming procedures even before the absurdity of ‘Dedalus’ or the trippingness of ‘Malachi Mulligan’ are remarked upon.

One whole chapter is notably given over to the bafflement of naming. It begins with ‘I’, the polar opposite to individual verbal labels, a pronoun without a noun. Unique among words, its meaning changes with every speaker. As Stephen intimates in a passing ‘I, I and I. I.’ (U 9.212), the meaning may even change for any one person—through time; ‘I am other I now.’ ‘Cyclops’, whose governing saints are ‘S. Anonymous and S. Eponymous and S. Pseudonymous and S. Paronymous and S. Synonymous’, contains ‘Adonai!’ in its terminal paragraph (U 12.1915), a word that looks and functions like a name but pointedly is not. It is in fact a substitute for one that is unspeakable and prohibited. ‘Adonai’ is making a nominal noise for a sacred onomastic absence.

One minor event in Ulysses is the devious misnaming of ‘M’Intosh’ by a collusion of oral, written, and printed communication. The mystery surrounding this figure is mainly due to its being given a name that we know to be chancy. If there had been no newspaper reference and if Bloom had wondered, at the end of his day, who the maninthe macintosh was, very little print would be expended on him. It is our knowledge of his pseudonymity that provokes so much curiosity. As naming, however, the procedure is true to universal type. What we wear can turn into what we become known by (Robin Hood may be a case in point; his sister Little Red Riding certainly is).

The misnomering integrated into the texture of Ulysses is intimately tied up with fiction, a process of feigning (or the invention of ‘figures’). As an obliging intermediary, Leopold Bloom assists in dissimulating the presence of M’Coy among the mourners (M’Coy is neither present nor mourning). Newspaper fictions get M’Coy as well as Stephen Dedalus, BA, into this second Nekuyia. In the midst of what looks like the least questionable list of mere names some fictions have intruded; we, in our superiority, translate the fictions into complicated actions and dysfunctions of information. We still don’t know who ‘M’Intosh’ is (some readers have thought they do, others claim we never will; but knowing who he ‘is’ would mean substituting his wrong name by one that is considered circumstantially plausible—a change of labels), but we recognize ‘M’Intosh’ as a series of mishappenings. Joe Hynes’s misunderstanding also shows the reporter’s need for labels of that sort. As we do not know the civil service data of the person who tells us what goes on in Barney Kiernan’s bar, we change this negative condition into a name and refer to him as ‘The Nameless One’, following a hint (U 15.1144). Namelessness is unsettling. So that in FinnegansWake we are striving for identification tags to attach to the paronymous noncharacters, and we co-create Earwickers and Porters, or pit Shems (in Hebrew shem intriguingly means name) against Shauns even where these configurations of letters do not occur, in the majority of cases, and we treat them as though they were friends of the family we would recognize anywhere.

Naming confers power. The namer feels superior to the namee (who is generally a helpless infant). Once a name is given, it tends to stick. Only when we assume important positions, like Pope or King, may we choose our own different names. Writers can do it too. They can name themselves, or one of their figures, ‘Stephen Daedalus’ or ‘Dedalus’. Or they can title a prose work about a day in Dublin Ulysses, and we realize the potency of this when we consider what difference it would make if someone discovered that Joyce’s real intention had been something like ‘Henry Flower’ or ‘Love’s Old Sweet Song’, ‘Atonement’, or ‘The Rose from Gibraltar’.

ifwelookatitverbally

Naming is one of the many activities we find in Joyce’s cosmos, but a prominent one—of paradigmatic significance: an action through words. My exemplification is simply a renewed demonstration of a direction away from the stability of things or persons towards movement, change. Verbs, which here represent action, movement, processes, are less tractable than nouns (nouns are ideal for catalogues or filing cards), less easy to pin down. Verbs have more flexibility, or flexion.