9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

Blends actual places, events, and characters with cinematic portrayals of fictional and factual monsters.

Das E-Book Ingrid Pitt Bedside Companion for Ghosthunters wird angeboten von Batsford und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 461

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

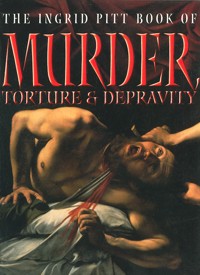

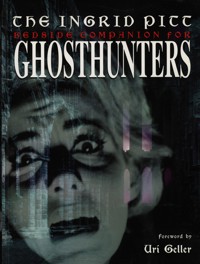

THE INGRID PITT

BESIDE COMPANION FOR

GHOSTHUNTERS

FORWORD BY

Uri Geller

CONTENTS

Foreword by Uri Geller

1 Introduction: The Grand Canyon

2 So What Is a Ghost?

3 Berkeley Square

4 Ghostly Gazumping

5 Spectral Guidance System

6 Around the Bend

7 The Dutchman

8 The Hills aren’t Alive

9 Sweeney Todd

10 The Man in Grey

11 London Bridge

12 Edward II

13 Possession and Danny Kaye

14 Highwayman

15 Equipment

16 Palfrey’s Bane

17 Casting Out Demons

18 The Boy

19 Portents

20 Trio of Death

21 Lawrence

22 Princess Diana

23 Nell Gwyn

24 Witchfinder

25 Dona Leonora Oviedo

26 Trains and Boats and Planes

27 Panic

28 Working Holiday

29 Hobby

30 The Ghostly Stool pigeon

31 Hitchhiker

32 Harry Price

33 Sparky Old Girl

34 Black Death

35 Drummers

36 Highway Ladies

37 James Dean – The Little Bastard

38 The Dark Cottage – A True Tale for Halloween

39 The Best Ghost Movies

FOREWORD

by Uri Geller

“ALL THE WANTED was for the hideous screaming to stop ...” “Deftly she stepped to one side and hit him in the face with the bloodied carcass ...” “Slowly, as the packing case tilted and tipped over to crush the trapped man, he heard the sound of the boy’s laughter rise and swell until it filled the universe ...”

There is only one woman who can chill the soul with such lush, theatrical gestures. Everything about her is magnified and distorted by a cracked camera lens – the Eye of Horror. When she wishes us to observe, she does not point – she extends an imperious finger, its nail sharpened to a rapier tip. When she wishes us to listen, she does not speak – she cascades words with sweeps of her gore-dipped quill. When she wishes to terrify, she piles up our nightmares and, with lashes of her whip, drives them over the brink into the Pitt.

She is the Countess Dracula. She is the Witch-Queen of the Screen. When she quietly asked if I would provide a few words for her new book, I recognised the request for what it truly was – an imperial demand that I could refuse at my direst peril. These pages are full of foolhardy mortals who thought the power of their reason was stronger than the supernatural. I am not that stupid. Or perhaps, after reading this volume at a single enthralling sitting, I am simply scared out of my wits.

Take the Countess’s book and place it by your bedside.

You may never sleep again...

Uri Geller

The Grey Lady

A lonely figure, breathless in the night

Fading, silently, softly out of sight

Re-appearing so tantalising and bewildering in the mind

Gliding gracefully, this ghostly apparition needs no place to hide

The air is still; no time to breathe

Your heart lurches and your chest begins to heave

Like a touch of earth upon your skin

The sudden cold makes you shudder within

You question your thoughts about the ‘Grey Lady’ being true

But her presence is known only to the Chosen Few.

Caroline Purser

1

Introduction: The Grand Canyon

Flat Tyre on the Oldsmobile

To bring the dead to life

Is no great magic.

Few are wholly dead:

Blow on a dead man’s embers

And a live flame will start.

Robert Graves To Bring the Dead to Life

IWAS LIVING in America. My marriage had just disappeared down the plughole, the theatre company I had been working for had folded its tents in the night leaving me and my beautiful daughter, Steffanie, with a clapped-out Oldsmobile, virtually destitute. When this sort of disaster strikes the only thing you can do is pass it down the line. The stiff upper labia revolves around cosseting your resources and to hell with everybody else. I followed the example of the departed stock theatre company, placed the carrycot on the passenger seat, the case with my gear in the trunk, let off the brake and freewheeled down the obligingly sloping drive from the boarding house to the road, kicked in the motor and headed out of town. It didn’t matter where, exactly, as long as it was over the State-line and my irate landlady might find it difficult to set the police on me. I was really in a bind. The little money I had I needed for baby food. Luckily petrol was amazingly cheap at that time so I was able to put some mileage under the threadbare tyres before they finally gave up what I must call the ghost if I am going to get a pun in this early.

A stroke of luck. I had the blow-out on a road that passed an Indian Reservation. Native Americans hadn’t figured much in my life up until then. Like everybody else I had a guilty feeling that they hadn’t been getting their fair share but, when you feel that your share seems to be even less, I can’t say you care a lot. Just off the road was a corrugated iron shack with car hubs nailed all over it. I hadn’t seen that sort of decoration before. They reminded me of the memorial shields you sometimes see in stately homes displayed along the beams. A youngish lad was stretched out at the side of the shed on a pile of tyres. As I approached, he opened an eye and watched me suspiciously. He brightened up considerably when he noticed the flat tyre on the Oldsmobile. He tried to sell me one of the tyres he had been sleeping on but when I asked him to fit it for me he admitted that it didn’t fit. He must have seen how upset I was because he came over all solicitous and promised he would get me a tyre. He knew where there was one that was practically brand new and I could have it for a quarter of its true value. I didn’t believe him but what other options did I have? He asked me to look after the store and disappeared. I sat on a tyre and let the misery hang out. An hour passed, two hours. I had just decided to push on with the flat tyre when a skinny little girl in a frock two or three sizes too big came shyly along the dust path and stopped a little way off. She just stood there saying nothing. I smiled and tried to look friendly. She didn’t respond. I had Steffanie on my lap so I turned her so that the little girl could see her. Little girls are always suckers for babies. Not this one! Babies meant hard work as far as she was concerned. I’d had enough. “What do you want?” I snapped. She looked as if she was about to run off but I quickly switched on a smile and she calmed down. “You’re to come with me,” she said quickly. “Whoa,” I thought. “Not so fast.” I’d heard about tourists who broke down and were never seen again. On the other hand what had I to lose? I had no money, a broken-down jalopy and a hunger that was mounting by the second.

I was expected. As I walked into the little collection of clapboard and corrugated iron shacks I could see dark, melancholy faces peering out at me. There was still the fear that I was about to become a statistic on a police blotter but I didn’t care. Around the back of what turned out to be the general store was a pile of junked cars. An old man limped out to see me and cuffed the girl around the ear as tactile confirmation that she had done a good job. She didn’t hang about but sped off towards the store. The man introduced himself as Johnny Running Bear and told me the girl was his granddaughter Rose. By this time I was weaving in and out of reality. I hadn’t had a proper meal for a week and that day had only eaten a packet of crisps and an apple I had picked off one of Johnny Appleseed’s trees by the side of the road. Everyone seems to be called Johnny in the mid-west. Johnny or Elmer. I slumped against the side of a rusted wreck and tried to explain my predicament. He wasn’t listening. He walked back towards his shack and called his woman. I found out later that was what he always called her. Her real name was Indian and translated as “Woman who walks forward.” She came out reluctantly. She was shortish with a wide flat face, very indigenous, and long, well-brushed, grey speckled hair. She took one look at me and hurried forward. She supported me and urged me towards her tiny house. Inside it was dark and furnished with seats and bits and pieces from scrapped cars. It was cool and I gratefully sank into a back seat salvaged from a Dodge. Woman fetched a scrupulously clean aluminium bucket of water and I gratefully washed the sweat and dust from my face. When I was refreshed she offered me food. I protested weakly. I didn’t mean it and tucked into the dish of beans and potatoes she put in front of me while young Rose fed a bottle of formula to Steffanie.

The upshot of it was that I stayed with Johnny and his family for a couple of months. I found them generous and kind but desperately unhappy. As much as I began to hate the authorities that had condemned them to a life on the poverty line in such a wealthy country as the United States of America, I had to admit to myself that much of their problems they brought on themselves. Instead of looking around and accepting what they had got and building on it they sunk their troubles at the bottom of a whisky jar and consigned their future to fate ... and to whatever smart Alec lawyers might be able to wrest from the US Government as restitution for the loss of tribal lands. I shot off a couple of letters to Jack Kennedy explaining what he should do. I obviously embarrassed him because he never wrote back.

One of the side lines that Johnny had was taking tourists down into the Grand Canyon. A couple of times a month he went and collected a dozen or so horses and a well-off cousin arrived with a mini-bus-load of would-be wranglers kitted out self-consciously in cowboy duds. Johnny allocated the horses and they set off down the long winding trail to the floor of the canyon. I desperately wanted to go but I was already sponging off his family and simply didn’t have the nerve to suggest that he put off a paying customer and took me instead.

Inevitably the time came when a would-be cowboy didn’t turn up. Johnny generously offered me the horse and I suddenly had doubts. Horses and me had never really got on. I would have liked to be able to smile sweetly and demur. That’s my problem. I always know the right thing to do but almost inevitably choose the opposite.

We left at dawn, Johnny leading the way and one of his sons playing tail-end-Charlie. I was just behind Johnny with Steffi in a basketwork frame attached to my chest. I was terrified. Not just for myself but for poor Steffi. What would happen if the horse tripped and fell or went berserk and plunged over the side of the canyon into the river far below? Gradually my confidence began to build as the sure-footed animal eased effortlessly downward.

It was afternoon when, without incident, we got to the prepared camp site by the side of the Colorado river. The other tourists thought that I was part of the management. I didn’t disillusion them. If they thought that I was a blonde, blue-eyed Iroquois why should I spoil their fun? That night we all sat around a roaring log fire and felt like hardy homesteaders. Unlike the homesteaders we had the comfort of knowing that our Indians were friendly. As the fire died down I got drowsy and cuddled Steffi closer to my body and stared into the glowing heart of the fire. Gradually the rising sparks and shifting logs began to form a face. A face I had loved and lost. My rational brain tried to tell me that I was building castles in the fire. My emotional brain didn’t want to know. The face that had formed in the golden embers was the face of my father. I also had the overwhelming feeling that he wanted to see my baby. Without hesitation I pulled the poncho I had wrapped her in aside so that her face was exposed and held her up so that he could see her. Tears cascaded down my burning cheeks. I swear he smiled and nodded before shifting logs destroyed the image and it flew, in a trail of sparks, up towards the moon now peeping over the side of the canyon.

I’ll never forget that experience and even now, if I’m feeling a little depressed, I think of that golden moment in the Grand Canyon with my baby and my father.

Well that’s my credentials for writing this book held up for scrutiny and probably found wanting. Found wanting because it is very difficult to describe exactly what a ghost is. In films the ghosts seen to be generally benign. The gruff but loving captain in The Ghost and Mrs Muir. The affable Topper and the follow-ups. Robert Donat’s puzzled Scottish laird, shipped to America with the stones of his castle in The Ghost goes West. Not so benign are the ghosts of Hamlet and Macbeth. There does appear to be a virtual cottage industry of houses with malignant natures and transport, in the shape of planes, carriages and ships, seems to get more than its fair share of infestation. All of these manifestations differ. Some ghosts are interactive. Others just hang around ineffectually watching their successor making the same sort of bloomers that they made in life. Usually the ghost manages, in some obscure way, to make contact with their beloved. Always toward the end of the film and always to get the living hero out of a hole. Need we look any further than Ghost with hunky Patrick Swayzse trying to get on earthly terms with the copiously weeping but magnificent Demi Moore and finally making the breakthrough with the aid of hilarious quasi-medium – Whoopi Goldberg?

2

So What is a Ghost?

If there are ghosts to raise,

What shall I call,

Out of hell’s murky haze,

Heaven’s blue hall?

Thomas Lovell Beddoes Dream Pedlary

GHOSTS HAVE BEEN with us since we dropped out of the trees and took our chances against the quadrupeds inhabiting the undergrowth. As one would expect, the Greeks and Romans did a very nice line in spectres returning to plague the living. The Greeks’ qualification for ghostship required that the person dying to give birth to his other dimensional self had to be killed or die in an abnormal way. Passing gently away in the arms of the family didn’t qualify. It was also believed that the spirits only slept and it was as well to pass through the cemetery very quietly or risk awakening them. The Romans wanted their departed spirits more amenable. The average ghost could be very helpful to career or love-life if approached properly and respectfully. Even so you had to be careful. If the departed spirit had departed from someone innately evil then the ghost could be something to be avoided.

China and India had plenty of roving spirits, most of them with a fixation about delivering as much misery and misfortune as they could to those still in a corporeal state. They also spent a lot of their haunting time in the guise of an animal: any animal as long as it could scowl and look reasonably ferocious. The problem is that they seem to get mixed up with other forms of fright-life like demons, vampires, ghouls, incubi and generally mayhem-inclined devils with horns, tails and fiery breath. Not exactly the ghosts I had in mind.

My sort of ghost has the same basic qualifications as a genuine, down-to-Hades vampire. It’s got to be dead. And it’s got to haunt something or someone. Benign or malign doesn’t matter. After all – it is possible that they are both different aspects of the same living person. It also has to be visible or at least have some marked effect on its surroundings. Shy, banging, groaning, plate-throwing, smell-projecting entities just don’t do it for me unless they can at least come up with a shadowy outline. When someone claims that they “know” there is a presence in the room because the temperature drops I’m not interested. Rising hairs on the back of the neck do nothing for me. Solid objects falling off the mantelpiece is interesting but not, of itself, a ghostly manifestation.

The islanders off the shores of Australia believe that the departed spirit, departed from the body that is, has a touch of the old Chinese Yin and Yang about it – Yin being “aunga” or good, Yang, the “adaro”, the evil side of man’s nature. After death ghosts go to live at the bottom of the sea or in a volcano. Some even make the journey to the moon. “Why” is the question that goes unasked. Ancient Egyptians also had some finely rooted ideas about what happens after death. They saw a sort of extension of the present form and made sure they were not mistaken for a fellah of the field by taking along whatever expensive goodies they enjoyed in life. This included food, animals, chariots, golden death masks and the odd handmaid or two. Ancient Egyptian ghosts obviously find their new circumstances so much to their taste that they don’t bother to return unless they happen to find themselves in a ghostlike form. Then they come back as either a deity, a pharaoh or a scarab beetle pushing a dung-ball across the sky. Like syphilis, ghosts know no boundaries and are to be found in every culture. Some, like the American Indians, believe that the spirit lives on forever and takes up residence in the trees, grass, wind or animals when it quits the earthly body.

The Christian religion, in many ways, makes the whole thing easy. When someone dies the spirit shuffles off into a state of limbo where it can ask all the questions it couldn’t get an answer to when in the solid state. Like why didn’t I win the lottery? Or why did Jayne Mansfield have bigger breasts than me? When all the answers are given and the value of the soul judged it is either consigned to hell or Heaven. Hell is just one long orgy in an overheated room with overloud heavy metal music. Hanging around on fluffy clouds trying to master the fingering on a harp and not lusting after angels and other assorted forms in see-through negligees is what you get if you’re handed a ticket to Heaven. Which means you get three shots at the ghostly manifestation business. One is the wandering around looking sad and lonely bag which results from the uncertainty of hanging around in limbo waiting for the call. Heavenly ghosts seem to have a penchant for appearing in sleazy sitting rooms in Blackpool, claiming to be an Indian Chief guide and telling the gullible – who have coughed up £10 each for a chance to hear something to their advantage – exactly what they want to know.

Most of the really good hauntings come from the third group who have been consigned to hell so, unless someone in the uncommitted world does something pretty magnanimous to right the wrong done by the unhappy spirit, the poor lost soul will not be allowed to pass upwards. Again I would like to quote Ghosts as a perfect case in point. When Patrick Swaysze dies defending the delicate Demi Moore he is in limbo, waiting for the outcome of his appeal that his sell-by date has been unjustly brought forward. When he is finally happy that everything has been done to make Demi completely unhappy and unfit for any further relationship in the real world, he is called to the other side in a blaze of joy. Not so the nasty “friend” who turns out to be the author of all Swaysze’s misery, Tom Goldwyn. He is dragged away to the fires of hell by a bunch of evil midgets in black habits with blazing eyes.

The Christian church may deplore the vehicle but the plot just about touches base on all the relevant points. There is a divergence between the ghost of the dead of the Protestant church and their rivals for the Holy Ghost’s favour, the Holy Roman Catholic Church. Basically the Protestants don’t believe that ghosts are after-life representatives of the dead, but evil spirits pretending that they are. Catholics generally accept that ghosts once lived a sentient, full-blooded life and do return in their altered form to pester the living – but only to ask for their prayers or to right an injustice.

Spiritualists – on the third spectral hand – believe that ghosts are graphics of souls that are earthbound because they have slipped through the system and don’t realise they are dead. That’s why they are eager to talk to any old biddy with a terrible hairdo, an aspidistra and a tom-cat that insists on marking its territory daily.

Dickens’ ghosts in A Christmas Carol were ghosts of a different ilk. These represented events – except poor old Jacob Marley, of course. He not only had to rush around in December with nothing but his winding sheets to keep him from disintegration but he had to drag the miseries of his life, the accounts and records ledgers, around on a great clanking chain.

Marley, like many other ghosts, was liberated from the brickwork by the night. Generally speaking ghost-lovers prefer to have the object of their disquiet rattle their chains at the witching hour. But it ain’t necessarily so. Versailles is a case in point. Nearly a hundred years ago two middle-aged ladies coughed up a couple of francs to have a vicarious thrill walking through the gardens and halls that hosted the best and worst of pre-Revolution French monarchs. They turned a corner and got more than their money’s worth. Strolling around on the lawn and through the ornamental gardens were scores of highly rouged men and women in eighteenth-century dress. As the ladies went out of the palace gates they mentioned to the man on the turnstile that they enjoyed the pageant put on for their benefit and were gobsmacked when he told them they were talking through their chapeaux. That stroll through the Versailles gardens in 1901 made the two English schoolteachers, Eleanor Jourdain and her friend Ann Moberly, famous. A year later Miss Jourdain returned and claimed to see a gardener who wasn’t there as well as not seeing a couple of labourers loading a cart – all in broad daylight. Since then, several other visitors to the palace have claimed to have had similar ghostly encounters but, as they had already been exposed to the writing by and about Mesdames Jourdain and Moberly, it doesn’t count. That’s my kind of ghost. Fancy-dressed, mobile and interactive. But there are all sorts.

3

Berkeley Square

I was not there, you were not there, only our phantasms.

T S Eliot The Family Reunion

LONG BEFORE LOVE-LORN Hooray Henrys mooned around claiming to have heard a nightingale singing, Berkeley Square was already famous for more sinister and less melodic sounds in the night. Number 50 not only had a ghoulish Victorian-style landlord, hand-wringing, ear-piercingly abused, innocent young girls and self-impaling sailors but, in addition, gave off a charge of static electricity that could knock your wig off – allegedly.

Now the house is indistinguishable from others around it. But a hundred years ago it was a mouldering ruin with little to recommend it but a clear view of the newly installed urinals in the Square. Its descent from a decent pied-à-terre for the hopefully upwardly mobile to a clapped-out derelict began in the middle of the nineteenth century when a Mr Myers was in residence. It could well be that, in fact, Mr Myers was the prototype for the fanciful lover out-warbling the mythical nightingale of Berkeley Square. Crossed in love by a young harpy who was no better than she should be, the sensitive Mr Myers retired into the back bedroom, roaming the house at night in a tatty nightgown by the light of a single candle and having intercourse, commercial as far as the story goes, with the son of the local general provisioner who supplied all his needs.

As the spurned suitor grew older and more malevolent and the house took on the superficial decorations of the dismal Frankenstein castle, its reputation for evil and supernatural visitations grew. It was claimed that the walls themselves became hostile to the outside world and that an incautiously placed hand could result in hair like a boxing entrepreneur and teeth fizzing out of the gums like popcorn on a hot griddle.

Out on the town for a weekend of trying to drink as many taverns dry as the King’s shilling could afford, a couple of sailors from the HMS Penelope ended up in Berkeley Square in what can only be described as a state of advanced rat-arsedness. By this time the moody Mr Myers had been called to whatever paradise blighted lovers are called and the house had become more of a wreck than during his neglectful stewardship. But the mist from the burns of Scotland had fogged up the eyes of the two jolly tars and, looking for a cheap place to rest themselves in preparation for the next days jollities, they kicked in the rotting front door, stumbled up the stairs and crashed out in the first place they could find that boasted some glass in the window and shelter from the chilly night air.

What happened after that can only be speculated upon. Zonked out on some rotting drapery, a whole foremast to the wind, it couldn’t have been very easy to awaken them. Something did. Something so mind-boggling that pink elephants dancing across the ceiling and rainbow-hued snakes squirming out of the walls paled to insignificance. In terror the two seamen rushed around like a second-rate cast on a Keystone Kops film before the more agile of the able-seaman saw the only way out – the faint outline of the undraped window illuminated by the guttering gas-lamps in the square below. The, by now, not so jolly tar, saw the light as his salvation and dived headlong through the glass. Like the old adage commands, he should have looked before he leaped. Before the Second World War demanded that all metal surplus to requirements should be turned into artillery and bombs to blast the evil Jerries, every self-respecting house sported a fine display of iron fencing. This was usually in the form of Roman spears, standing on end and braced by a connecting strut. As our leaping able-seaman soon found out when he ignored the adage and plummeted down at 32 feet per second. His anguished cries as he hung from the steel shafts embedded in his rectum, à la Edward II, were only slightly less pitiful than his shipmate’s, whose mind had been completely short-circuited by whatever he had seen and who was huddled in a corner making disgusting un-animal noises.

Even in those days, Berkeley Square was inhabited by the gambling set. Gambling really meant gambling then. None of that nipping down to Hill’s for a flutter on the 3.30 at Ascot. Wagers were made mano a mano on practically anything: water running down a window pane, who has a hole in his sock or, visions of Les Liaisons Dangereuse, who could bed the latest virgin on the block in the shortest time.

The reputation of 50 Berkeley Square had grown so rapidly that it was a major topic of conversation at the soirées and salons that made life bearable for the chattering classes. At first the hard men and gamesters ignored the tittle-tattle: they didn’t believe in the supernatural. You had to put your faith in real, solid, charms like a well-mounted rabbit’s foot or a hair from the tail of a horse that had won a race and been struck by lightning and survived. Very efficacious – the latter.

Still the stories of odd goings-on at Number 50 persisted – and were embellished. The story of a pretty maid taken into service by a lascivious employer and kept locked up in an attic room was a big favourite. It was posited that it was the unquiet shade of this poor, distressed creature that had so terrified the sailors on leave that one had ended up spiked and the other screamed out his eternity in Bedlam. It was a tale that fed the public imagination and, before long, there was a whole bunch of quivering psychics ready to swear to having seen the pale tortured face at the upstairs window, pleading to be delivered from the unnatural advances of her lecherous master. The Victorians were big on lecherous landlords and simpering virgins. The gaming classes also had an interest in virgins – simpering or plain – as long as they were willing.

Then a Mr Bentley, either an extremely foolhardy bloke or an out-of-towner who hadn’t heard the tales that were freely circulating, took on the lease. He moved in with his household and set about bringing the house back to something approaching its former semi-grandeur. Not an easy task. It wasn’t just that the house was decrepit. There was also the smell. It wasn’t just that every dosser and blade with a bladderful had used it as a stand-by urinal for a couple of decades. It wasn’t that every pigeon from Waterloo to Trafalgar Square had unloaded in the unglazed rooms. Or that rats had proliferated, died and rotted in the variety of excreta and dust that had dominated the rooms for years.

There was another, unearthly smell. The smell of Satan’s Inferno was the generally accepted opinion. Mr Bentley, an investment made, wasn’t to be put off by the objections of his nasally sensitive family and declared the refurbished house ready for occupation – and hired a maid. The maid, Alice Warmsley from Walthamstow, was not what you might call romantic. She had spent the first 14 years of her life working in her uncles’ tanning pit and had a skin that had absorbed more than a little of whatever it is they rub into untreated skins. Being taken on as a skivvy was a major breakthrough for the Warmsley family and Alice was determined to return to Walthamstow a lady – well, at least a lady’s maid.

To Alice the house smelled like a dawn walk in the Vienna woods after the tanning sheds of her childhood and she settled into the garret without a problem. Bentley was grateful for this. Now if his daughters continued to complain he could point to the maid’s easy acceptance of what was positively the worst room in the house and make sneering remarks about their fragile understanding of the world about them.

For a while it almost seemed that his hearty insistence that nothing was wrong was going to work. Then one of his daughters brought her boyfriend home for a weekend of family fun. The only room where the gallant captain could fit in, other than the daughter’s – and Bentley wasn’t having any of that – was the room that had proved so ruinous to the sailor boys and frequently displayed the ill-used maid at the window. Bentley offered his daughter’s suitor the fatal room but first warned him of its reputation. The young soldier, aware that the room was only a short distance from that occupied by the frisky object of his lust, smiled deprecatingly and claimed that he would sleep in no other room.

A striking example of loins speaking before the brain is in gear!

Alice was dispatched to make the room ready. The family was downstairs taking tea and listening to the tales of derring-do that the captain was embroidering for them when the bone china came to the edge of disaster as a blood-chilling scream echoed through the house. Those in the parlour sat en tableau for seconds before Mrs Bentley gave a fair imitation of the primal scream, daintily replaced the Daltonware on the sidetable and swooned. Bentley was of sterner stuff and leapt to his feet. “Come with me!” he ordered his martial guest and ran from the room. The captain, who would have preferred to stay and bring solace and comfort to the ladies, reluctantly followed.

They found Alice standing in the middle of the bedroom, a newly ironed sheet crumpled between her hands, staring wide eyed in the direction of the window. Bentley spoke sharply to her but she didn’t react. She stood, rigid as a day-old corpse, her mind locked in some place not accessible to the others. Nothing they could do could bring her out of her trance so the benevolent Bentley had her stowed safely away in her garret and gave his guest the opportunity to forget the idea of staying over and return to the safety of his barracks. It was no good. The captain’s lust made him impervious to any argument that the older man might put up.

So the household retired to bed.

The captain gave himself a good scrub down with carbolic soap and waited for the wee small hours when his beloved’s resistance would be at its lowest ebb. The tryst was not to be. The family were awakened by the sound of a pistol shot. When they managed to break into the guest room they found the captain dead – his face a mask of horror. From the attic came the sound of insane laughter. Alice was packed off to a hospital the next day and died, insane and uncommunicative, a short while after. The captain’s death was put down to a brainstorm.

All this excitement added to the house’s reputation and, from being a subject for idle conversation, became a source of interest to the gambling classes. Here was a readymade set-up that could only gain by notoriety. The dare was set. A thousand guineas for anyone who could spend a night alone in the house. First up, and last, for what looked like easy money, was Sir John Warbouys. Known as a committed drinker, esoteric gambler and a self-acclaimed lady’s man, he accepted the rules of the challenge. He must enter the room before midnight, must be completely alone and could only carry a small side-arm. As a concession he was allowed a bell. This he could give a playful tinkle on the hour to show he was still up for the game and, if he needed assistance, he would ring the bell as frantically as the conditions dictated. The Knight sank a large port and brandy, said goodnight to his adjudicators who were to spend the night outside in the garden, and retired.

An hour later came the first all-clear signal. By this time the witnesses were wishing they were somewhere warm and comfortable and trying to think up an excuse to slide off to a well-frequented establishment on the other side of the square. For the second time the bell rung out and the gamblers grunted their disgust and settled down deeper into their blankets and coats. They never heard the bell again. Whether this was because they all went to sleep or because it never rang again is open to dispute. Naturally the witnesses refused to admit that they had nodded off, but if they weren’t asleep why didn’t they remark on the fact that the bell didn’t ring. Hadn’t they read Conan Doyle?

When, finally, they decided to look in on Sir John, they found him in exactly the same condition that Mr Bentley had found the captain. Dead with his features hideously distorted.

What manner of apparition could cause the death of hardbitten men just by its appearance? Was there something about the house’s history back beyond the broken hearted Mr Myers that could account for the reign of terror that had invaded the house?

Well, there was the multi-talented parliamentarian, George Canning who, when he wasn’t sorting out difficulties in South America, lived in Number 50. Perhaps he was up to something untoward. Maybe he ran a concession from the recently disenfranchised Hellfire Club in the attic. Or brought back some devilish voodoo practices from South America. Probably not. When he died in 1827 the house was bought by Miss Curzon of the famous Curzon family who owned big tracts of land in that area. She died in the house at the grand old age of 90 and never complained of anything untoward. So maybe she was the malignant spirit?

Again unlikely.

Mr Myers, who bought the house from her executors and, after being dumped by his fiancée, spent the rest of his life wandering around the house in his nightshirt lit only by a farthing candle, was never known to comment upon any supernatural activity.

Let’s be uncharitable and pile it all on to Myers. Maybe his heartache extended beyond the grave and he wanted everybody to know about it and suffer. And maybe the reason that the present occupants – the antiquarian booksellers, the Meggs Brothers – have reported no death-dealing apparitions is that Mr Myers, firmly ensconced in the theoretical hereafter, has either won over his lost love or found someone else to supplant her in his affection?

*

In 1933 Jesse Lasky, the man who made Hollywood, produced a film written by John Balderston, the exjournalist responsible for rewriting the Dracula stage play of Hamilton Dean’s London success and making it into an American blockbuster, called Berkeley Square. The plot is about a house, surprisingly, in Berkeley Square, that takes pity on its owner, who isn’t getting a fair deal by the local female populace and catapults him 200 years into the past when, evidently, time travellers had a far better time of it amatorially. Leslie Howard played the lead in his usual frail manner and Heather Angel matched his delicacy as the girl from long ago. Matching the general limp-wristedness of the film was the directing of Frank Lloyd. It was all very languorous and the script couldn’t miss the opportunity of inserting a few cunning déjà vus into the fabric of the past.

The events in Berkeley Square, the movie, in no way echoed the fatal confrontations in Number 50 but it is interesting that the writer should pick Berkeley Square as a setting for the whiplash into the past. The book from which Balderston wrote the screenplay was by Henry James, A Sense of the Past. It’s more than a little likely that James had heard the tales told of Number 50 Berkeley Square and decided to give the disquieted spirit of Mr Myers a solution to his problem. A trip to the past and a lady who would indulge his habit of wandering around in his nightshirt.

Whatever the basis for the story, it was considered good enough to get a further outing in 1951 with the more robust Tyrone Power taking over the Howard role. Christopher Reeves, then the incumbent Superman, decided the story was the sort of delicate métier he needed to prove his worth as an actor away from the supernormal exigencies of his man-of-steel character and reprised it as Somewhere in Time. Another location switch and the 6ft 4in Reeves trying to look and act like the effete Leslie Howard. Not a pretty sight. Jane Seymour, the love interest, is at her most beautiful but somehow never manages to make the time-lock.

And, of course, that was the end of any connection with the haunted house in the heart of Mayfair.

4

Ghostly Gazumping

Thou canst not say I did it: never shake

Thy gory locks at me.

William Shakespeare Macbeth

IF THIS IS LONG ISLAND it’s got to be Amityville. Which means 112 Ocean Avenue. And we all know what that means. The little seaside resort of Amityville was in the wallow between Trick or Treat and the hypocrisy of Thanksgiving. Usually a time when nothing more exciting happens than deciding whether the Halloween costumes can be put away for use again next year and trying to think up an excuse for not inviting the new neighbours around for turkey and toasted marshmallows. Except at Number 112 that is. Ronald De Feo, one of the sons of the household, found his bank balance wasn’t keeping pace with his spending habits. So he took a gun and ventilated the rest of the family, his parents, two sisters and two brothers, where they sat. His rather unoriginal plan was to blame some unknown marauder, wait until the resulting hue and cry ran itself out and then slope off to spend the quarter of a million dollars his father had thoughtfully insured the family for. Having done the dreadful deed Ronald worked himself up into a Stanislavskian sweat and dashed into the nearest bar and sobbed, cried and screamed as he told the tale of how his family had been slaughtered. Unfortunately for Ronald the local police chief was a simple man who worked on a simple premise. In a case of murder you first suspect the hysterical witness who has witnessed the slaughter but has miraculously survived. Ronald fitted part one. Next was who benefitted most from the crime. Ronald was up for that one as well. Fingerprints on the gun, bloody footprints in the hall and witnesses to the actual trigger-pulling weren’t as reliable as the old and tried theories so the Sheriff arrested Ronald De Feo and he was subsequently handed down six life sentences to run consecutively.

In the year that the old house stood empty it picked up a bit of a reputation. Strange lights, unearthly shrieks and a good deal of grunting and groaning was heard at night but this was put down to the manifestations of the hot-blooded younger generation. As long as the teenage pregnancy rate didn’t rise too steeply, no one felt called upon to do anything about it. Anyway, a new family had already slapped down a deposit and were threatening to move in immediately.

The new family were the Lutz, Kathy and George and their offspring – a five-year-old daughter, Missy, and two sons, Danny and Chris. This was 1975. The year Saigon fell and Karpov got a walkover in the chess championship when Fisher failed to show. A year of little excitement unless you happened to be on the spot. And it seems that the Lutz family were on the spot. George was up to his hairpiece in alimony and his construction business was on a downward slide. He might not have been so pushed if it wasn’t for his wife’s insistence that it was time for them to move up in the world. Deer Park might sound nice but it was in a low-rate area and didn’t impress their social climbing friends. When George heard the asking price, he couldn’t believe it. It was a bit more than he was paying at the time but the push to his upward mobility would more than compensate for the extra money he would have to find. At least that was the general thinking which dominated the build up but was out of the window almost before they installed their obligatory rubber plant in the living room. But it was too late to bow out gracefully. There was work needing urgent attention. The drains had silted up and rain had seeped in during the year that the house had been uninhabited and plumbers and brickies don’t work for nothing. George decided he would have to do the work himself. He had the skill but was woefully short on motivation by this time.

At first his guileless remarks to neighbours about black gunge flooding up through the drains and dark patches appearing on the walls were merely stated facts. His audience, generally speaking, had a more colourful imagination. Before long the gunge was congealed blood and the dark patches bloodstains. These solid manifestations were linked with the shrieking, moaning and general background noise heard when the house was unoccupied, and a legend was born. George, to be fair, just went along with his neighbours to begin with. It gave him an excuse for not being more eager to bring the condition of his dilapidated house on a par with his neighbours. The more the stories circulated the wilder they became. Before long George and Kate had forgotten what was real and what had been invented for, and with, the neighbours. Once the idea that the home was actively working against him had taken root everything that happened took on a sinister aspect. At least it distracted him from the unpalatable fact that he was heading for a nasty appointment with the bankruptcy court. The expense of keeping up with the Rockefellers was prohibitive. But at least he had an excuse. Now there wasn’t just the slime in the bathroom and the blood on the wall to contend with – the slime became a stinking morass and the stain actually exuded glutinous globules of blood. This attracted millions of flies and the smell became unbearable. Then the symptoms of supernatural possession became physical. Kathy was in the bathroom about to step into the bath when she felt strong arms encircle her. Her husband was out and it was the gardener’s day off so she let off a shriek and fought her way out of the bathroom, The proof that the arms were at least unusual were the livid weals that covered Kathy’s body. George was sympathetic but he had his own tale to tell. He had woken up in the night to hear the martial sounds of a band. A marching band. The crashing cadenzas of the music and the tramp of marching feet shook the timber-framed house to its foundations. Again it was Kathy’s turn to feel the force of whatever was spooking the house. They had both just dropped off to sleep when she was jolted awake by a falling sensation. Her scream jerked George awake and he stared open mouthed. Kathy was hovering several feet above the bed bathed in an unnatural glow. Before George could move the light snapped on and one of the children, woken by the ruckus, appeared in the door. The interruption short-circuited whatever force was levitating Kathy and she crashed back onto the bed.

Things started to hot up after this. Now the place was besieged by huge hooded figures that walked through walls and appeared at inconvenient moments – although only when the family were alone. The hooded ones were joined by a grotesque demon with only half a face. The other half looked as if it had been blown away by a shotgun. Evidence of an earlier haunting that had not worked out too well for the ghoulish figures?

By this time George had become unhinged. What with his business worries and keeping the family funny business alive he had jumped the final cog. He was now convinced that he was a reincarnation – if you can be a reincarnation of somebody still alive – of the murderous Ronald De Feo. Never a day passed without his reporting some new and unexplainable occurence. One night, for no apparent reason, the family were jolted out of their sleep by a tremendous crash from below. When George went to investigate he found the heavy, solidly fashioned front door ripped from its hinges and lying in the hall. On further investigation the following morning he found that the garage door had been vandalized to such an extent that it needed replacing.

And then there were footprints! Not any old footprints – cloven-hoof prints in the snow. You might think that any normal household would have packed what was to hand in the nearest duffel bag and been long gone by now. Maybe it was George’s newly acquired persona as the De Feo doppelganger that kept him at the centre of things. Whatever it was, he was still willing to face it out.

Until the night of the fiery eyes. These were seen by the six-year old daughter. They seemed to float outside the kitchen window glaring malignantly at those within. That was enough for Kathy. George she could cope with. Levitation had its lighter side and, hey, what’s a phantom cuddler between sharing entities. But fiery eyes outside the kitchen window was too much. By the morning the family was long gone – and the mortgage company could whistle for its money!

Naturally by this time the Amityville Horror had hit the press. Each time it was strained through a different reporter the story was reinvented and embellished. De Feo’s lawyer saw the mounting histrionics over the supernatural inhabitants of the house as a basis for an appeal. Ronald De Feo had always maintained that voices had implanted in him the undeniable urge to slaughter his family. His lawyer now tried to convince a judge that the demonstrably malignant nature of the house was the basis of any argument for a retrial. The press loved the story. It was all hearsay and malarkey but when straight-laced lawyers tried to convince sceptical judges that it was all true, they had a field day.

When Jay Anson finally decided to write the book in 1978 the Amityville Horror was so well known that it was hard to find an angle that hadn’t been exploited. So, using the minimum of poetic licence, Jay got together with George and wrote the story. Before the book was off to press the story had been snapped up by the film company INT/Americana.

Although the whole affair might seem just a little OTT the overwhelming success of first the book and then the screenplay stirred up the main contributors to the story, the witness De Feo, the lawyer William Weber, “Father Mancuso,” the exorcist, Jay Anson and the whole of the Society for Psychical Research. Soon everybody was suing or threatening to sue every one else.

At the box office the film was going from success to mega-business. James Brolin and Margot Kidder headed up the cast as the stressed-out George and the over-wrought Kathy. Rod Steiger came in and, just in case anyone was in any doubt that the story was in any way fruity, played the priest as if he was giving acting classes to a bunch of walkabout deaf Aborigines who had knocked off his toupee. The music, by Lalo Schiffrin, did get an Oscar nomination and the film was acclaimed by the box-office tills.

Not willing to let a good thing slide silently under the table the Amityville Horror was quickly followed by exploitation movies of ascending direness and an unbelievably bad TV series.

The capper is that the new owners who took over the house sued George Lutz, and won on the grounds that their peaceful existence in the house was disturbed, not by entities from beyond the great divide but by tourists who couldn’t get enough of the place. George Lutz and Jay Anson, together with the producer, had to cough up over $1,000,000. Even the lawyer Weber had a go at the much misused Lutzes claiming that the whole shebang had been a put-up job between George and Anson with the idea of writing the book the prime objective. Can the path of literary endeavours ever have been so fraught?

5

Spectral Guidance System

...ghosts are fellows whom you can’t keep out

T.S. Eliot A Fable for Feasters

PUT ERROL FLYNN in a snug pair of tights, comb in a bouncy page-boy hair-do and top it with a cute little green hat with a long feather and what have you got? A hearty, butch Robin Hood. Immaculate dinner jacket, quizzical eyebrows, a fastidious need to be shaken and not stirred and a penchant for killing off his second lead ladies gives you an exciting James Bond. Even diddy Dudley Moore, navel high to the statuesque Bo Derek and getting a ten for ambition is still within the parameters demanded of a sexy lead character in an overbudgeted film.

But Richard Dreyfuss!

It takes a bit of imagination on the part of the audience to squeeze chubby little Dickie, with his perpetually petulant expression, into the heroic mould. It’s what they call casting against character. In the film Always it is definitely that. Dreyfuss is cast as a devil-may-care pilot. Not just any old pilot but a gung-ho fire-fighting pilot. His job is to bomb forest fires with foam extinguisher. This calls for real low-level stuff, snapping off the top branches of blazing trees whenever the camera is in the right position. Love of his life – and subsequently his death – is feisty little Holly Hunter, also a pilot but more often the voice on the radio reminding our heroes what their job is. Inevitably Dreyfuss goes a bush fire too far and dies trying to return to base. Luckily for the film, although dead, he refuses to do the decent thing and go to the pilot’s heaven. Holly Hunter wanders around for a while with a sorrowful face and a glycerine tear or two before falling for the masterful charms of replacement pilot John Goodman. All this is observed at close quarters by the defunct Dreyfuss. Understandably he is a bit miffed to see his bereaved girlfriend heading towards connubial bliss after only ten minutes’ sprocket time and tries to influence her into giving the presumptuous toerag the big E. But another forest is out of control and another squad of gallant fire fighters is trapped in the encircling flames. The new boyfriend wants to show his prowess but Holly Hunter has been there before. Anyway, women’s lib dictates that somewhere in the picture Holly has to turn off the waterworks and take control. So while everyone else is discussing the best way to put out the fire she sneaks off and takes the plane up into the wide blue yonder. Sitting in the co-pilot seat – but of course unknown by Holly – is concerned Richard Dreyfuss.