Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Stalag VIII-B, Colditz, these names are synonymous with POWs in the Second World War. But what of those prisoners in captivity on British soil? Where did they go? Gloucestershire was home to a wealth of prisoner-of-war camps and hostels, and many Italian and German prisoners spent the war years here. Inside the Wire explores the role of the camps, their captives and workers, together with their impact on the local community. This book draws on Ministry of Defence, Red Cross and US Army records, and is richly illustrated with original images. It also features the compelling first-hand account of Joachim Schulze, a German POW who spent the war near Tewkesbury. This is a fascinating but forgotten aspect of the Second World War.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 337

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my wife, Veronica

We have not eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.

Lord Henry Palmerston, 1848

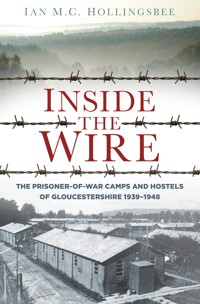

Back cover: painting by ‘The Corporal’, the late Ken Aitken GAA, of American Military Police with German POW at Moreton-in-Marsh railway station, Gloucestershire. (Reproduced by kind permission of Gerry Tyack of the Wellington Bomber Museum, Moreton-in-Marsh.)

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

List of Abbreviations

Foreword

Preface

1 Introduction

2 Camp 37:

Sudeley Castle, Winchcombe

3 Camp 61:

Wynols Hill near Coleford, Forest of Dean

4 Joachim Schulze:

An account of his time as a POW in Newtown Hostel

5 Camps 649, 554 & 555:

Company (Coy) Working Camps for Italian Co-operators

Swindon Village Camp 649

Woodfield Farm Churchdown Camp 554

Newark House Hempstead Camp 555

6 Camp 157:

Bourton-on-the-Hill

7 Camp 185:

Springhill Lodge, Blockley

8 Camps 702/7 & 702/148:

RAF Staverton and RAF Quedgeley

9 Camp 142

Brockworth and Quedgeley Court

10 Camp 1009

Northway Camp, Ashchurch, near Tewkesbury

11 Camp 327–232

Northwick Park German POW Hospital

12 Camp 263

Leckhampton Court, Cheltenham

Notes

Copyright

Acknowledgements

The following people and societies have been helpful with this research and I am most grateful for their support and encouragement: American Red Cross Archives, Maryland, USA; Ann Hettich, Campden & District Historical & Archaeological Society (CADHAS); Barbara Edward, Curator at Sudeley Castle; Barry Simon and Hazel Luxon, Swindon Village Local History Project; Brenda Mitchell and Enid Becker of Gloucester U3A; Eric Miller, Leckhampton Local History Society; Gerry Tyack, Wellington Bomber Museum; Gloucester Coroner’s Office; Gloucestershire Archives, Alvin Street, Gloucester; International Committee of the Red Cross in particular Daniel Palmieri, Historical Research Officer, Geneva; Jean Clarke, National Secretary of Catholic Women’s League; John Dixon, President of Tewkesbury Historical Society; John Malin, Blockley Antiquarian Society; John Starling, Lt Col, Royal Pioneer Corps Association; Malcolm Barrass, Flt Lt ex-RAFVR(T), RAF History Society; National Monuments Records, Swindon; and The National Archives, Kew. For help with translations, I am indebted to: Gary Costello and Theo Hunkirchen for German translations; Sara Tozzato for Italian translations; and Catherine McLean for French translations. I am grateful to those former prisoners of war and their relations, who were kind enough to share their stories: Joachim Schulze, German POW, and his son Thomas; Theo Hunkirchen and Peter Engler, sons of German POWs; Marilyn Champion, daughter of Italian POW. Thanks also to: Alan Lodge, Alex Smith, Andrew Power, Bill Hitch, Brenda Mitchell, Carol Minter, Clare Broomfield, Colin Martin, David Evans, Ian Hewer, Jack Johnson, Jane Giddings, Jean Clark, Jeremy Bourne, Jerry Mason, Mario Redazione, Peter May, Rosemary Cooke, Shirley Morgan, Stephen Pidgeon, Trefor Hughes, Zosia Biegus – and the many others who have emailed or called with useful clues and information.

A special thank you to two very good friends who have read, encouraged and criticised when needed: Brian Millard and Joachim Schulze. Finally, I owe a great deal of thanks to Roxy Base for her skill and expertise in editing and proofreading my work.

(Sadly both Joachim Schulze and John Malin died towards the end of my research and I am most indebted to them both.)

List of Abbreviations

The POW Camps in Gloucestershie and their Associated Hostels

Location of POW camps and associated hostels.

Map Ref.

Camp No.

Main Camps and

Administered Hostels

Location

Grid Ref.

Comments

1

37

Sudeley Castle

Winchcombe

SP 030278

Estate & gardens restored

2

Newtown, Ashchurch

Tewkesbury

SO 904 330

Canterbury Leys PH Beer garden

3

Sezincote

SP 173 311

Exact location not found *1

4

Moreton-in-Marsh

SP 204 321

Residential housing

5

Alderton

SP 000 332

Exact location not found *1

6

61

Wynols Hill

Coleford

SO 586 106

Housing estate *2

7

Ross-on-Wye Drill Hall

SO 601 241

Now Registry Offices

8

Highnam Court

SO 796 192

Private grounds, now only lawns

9

Churcham Court

SO 769 182

Private land, some huts remain

10

Llanclowdy

Herefordshire

SO 492 207

Farmland

11

124

Wapley, Yate

Bristol, S.Glos.

ST 71 79

Location not found, extensive search *3

12

124a

Ashton Gate

Bristol, S.Glos.

ST 569717

Camp and caravan site *3

13

142

Brockworth

Gloucester

SO 890168

Allotments and housing

14

142

Quedgeley Court

Gloucester

SO 813153

Industrial area, house no longer exists

15

157

Bourton-on-the-Hill

SP 160 321

Forest area

16

185

Springhill

Blockley

SP 132 357

Private land, some huts remain

17

Over Norton

SP 313 285

Exact location not found *1

18

Burford

SP 251 121

Misspelt as Burforf on report

19

Stanton

SP 069 342

Exact location not found *1

20

Bodicote

SP 460 378

Near Banbury, Oxfordshire

21

Horley

SP 418 438

Near Banbury

22

263

Leckhampton Court

Cheltenham

SO 945 193

Now Sue Ryder Home

23

Siddington

SU 050 992

On airfield

24

Elmbridge Court Farm

SO 863 196

Under Glos. Ring Road

25

Hunt Court

SO 903 176

Private house

26

Chesterton

SP 012 003

Farm near Cirencester

27

Woodchester Lodge

SP 839 023

Private house

28

Northleach

SP 111 146

Exact location not found *1

29

327/232

Northwick Park

Blockley

SP 168 365

Business park, some huts remain

30

Coy/554

Newark Farm, Hempstead

Gloucester

SO 816 174

Private accommodation

31

Coy/555

Woodfield Farm

Churchdown

SO 889 190

Pasture

32

Coy/649

Swindon Village

Cheltenham

SO 936 249

Private house

33

702/7

RAF Staverton

Gloucester

SO 884 221

Staverton Airport *4

34

702/148

RAF Quedgeley

Gloucester

SO 810 141?

Kingsway Estate. Exact location not found *1

35

1009

Northway, Ashchurch

Tewkesbury

SO 924 340

Housing estate

Notes:

*1 The exact location of these camps could not be verified or was outside the county.

*2 Wynols Hill near Coleford was also spelt as Wynolls Hill in some reports.

*3 Wapley in Yate Camp 124 & Ashton Gate Camp 124a. The author’s intent was to include the two main camps of South Gloucestershire but despite the grid location for Wapley being recorded as ST 7179 no trace of this camp could be found. Extensive enquiries found no records at the International Red Cross or at The National Archives. Given these facts the author has restricted the research to the current county of Gloucestershire.

*4 Most RAF camps in Gloucestershire housed some German POWs; RAF Innsworth (very close to RAF Staverton) held 127 German POWs in July 1947.

Whilst every effort has been made to ensure precision of grid references used throughout they are for reference only and cannot be used as directions to the exact locations of the camps. Point of interest may be on private or protected land, so please seek landowners permission before gaining access. Readers are encouraged to exercise caution and stay on public footpaths.

Foreword

(Joachim Schulze had agreed to write this Foreword but sadly passed away before it was completed. He did discuss it with his son Thomas, who has sent these words on his father’s behalf.)

I am writing a few words on behalf of my father Joachim Schulze who passed away in January 2013 at the age of 86. He spent approximately two years as a POW in England. He was very happy and proud to be mentioned in Ian Hollingsbee’s book. The last couple of years of his life he devoted to working on this period of his youth, also writing an article for the Tewkesbury Historical Society Bulletin 2012.

The time he spent as a POW in England were very formative years, which helped him revise his war experiences as a young person and especially to deal emotionally with the atrocities he witnessed in the Netherlands in 1944. It convinced him of the importance of being aware of political issues and made him a stern proponent of social democratic values.

He was still able to read most of the chapters of Ian’s book and it made him content that this part of history will not be forgotten.

Thomas Schulze, 2014

Preface

Two years ago I spent a night in the old German guard quarters at Colditz Castle in East Germany. Colditz was supposedly an escape-proof German prison fortress for Allied military officers, from all services, who were persistently trying to escape from other prisoner-of-war camps in the occupied territories during the Second World War.

On my return to England I was surprised to note how very little had been written about the many thousands of Italian, German and other Axis forces that were captured and held as prisoners of war (POWs) in Britain, the USA and Commonwealth countries. However, one book by Sophie Jackson entitled Churchill’s Unexpected Guests – Prisoners of War in Britain in World War II (published in 2010) immediately aroused my curiosity as to whether or not there had been any prisoner-of-war camps within Gloucestershire.

What was it like to be a POW in Britain, knowing that your own country had been defeated? Further, what were the conditions facing these prisoners and how did they cope with captivity?

The source material for this investigation is drawn from a wide range of public records, the personal accounts of those who remember our ‘unexpected guests’, and from some of those who were themselves the ‘unexpected guests’. The final German POWs left these shores in 1948, some sixty-five years ago, so that even the very youngest POW would now be well over 80 years old.

So many times during my enquiries I have been told that a certain named person would have helped me with my research if only they were alive today. Nevertheless, I have tried to maintain the essence of individual witnesses and I am very grateful to the many people who have contacted me, including one Italian and three German POWs who spent some of their war in the county of Gloucestershire.

Searches were conducted at The National Archives at Kew, the National Monuments Records at Swindon, and the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva. However, many camp files have not been retained. This has resulted in a significant amount of material for some camps in the county, but very little in relation to others. Records relating to the POWs held by the Americans are not available in the UK and have, therefore, proved difficult to trace. I am most grateful to those American archivists that were approached for their helpful assistance.

I have drawn on the published reports by English Heritage and others which state that each POW camp in Britain was given an official number from 1–1,026. They were then further identified by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) as being used as base camps, reception camps, special camps (or cages) and Italian, German or other Axis working camps.

Camp numbers were sometimes changed or, as in the case of two of the Gloucestershire camps, were given identical numbers. In addition to these base camps and other types of camp there were significant numbers of hostels throughout the county, one of which housed over 300 POWs. The hostels and billets identified within this work were generally managed by a main camp, sometimes not the closest one. There will be some hostels that have eluded me or I have been unable to locate. Those that remember POWs were children at the time of the Second World War or have been told about the POW hostels by others. Often these hostels were then mistakenly referred to as POW camps.

All the British POW camps within Gloucestershire were working camps and held non-commissioned officers or other ranks. The only exception to this was medical officers who were designated as protected personnel under the Geneva Convention. POWs within these working camps were sent to where their labour was required and where such work was permitted by the second version of the Geneva Convention of 1929. This included agricultural work, which was often seasonal, and other labouring jobs. As a result, POWs were frequently transferred between different locations, hostels, billets or camps.

Ian Hollingsbee, 2014

1

Introduction

Neville Chamberlain, Britain’s prime minister, broadcast from the BBC that we were at war with Germany on 3 September 1939. He then appointed Winston Churchill to be the First Lord of the Admiralty.

THE FIRST PRISONERS OF WAR ARRIVE

The first recorded prisoners of war (POWs) in Britain were Luftwaffe aircrew who survived after being shot down or having to crash land, or those submariners who were lucky enough to have survived a Royal Navy or Royal Air Force attack on their German U-boat. Very few U-boat crews that were either torpedoed or depth charged, and subsequently sunk, survived the ordeal. One internet search concluded that out of 40,000 U-boat personnel involved in the Second World War only a quarter lived to see the end of hostilities.

The first U-boat crew to be taken prisoner were in U-boat 27, which was captured in the North Sea with its entire crew on 20 September 1939. This submarine was a type VIIA and had been commissioned on 12 August 1936. The boat had a very short career, however; under her commander, Johannes Franz, she had only one war patrol before being hunted down and sunk, to the west of Lewis in Scotland, by depth charges from the British destroyers Forester, Fortune and Faulknor. Thirty-eight submariners survived that attack and spent the entire war as prisoners of war.1

Two POW camps were made available to the War Office in 1939. Camp 1 was situated at Grizedale Hall, Grizedale, Ambleside, in Cumbria. This was a base camp for the reception of captured German or other Axis officers and was described as a ‘county house’; it contained thirty huts, with a double perimeter barbed-wire fence and a number of watchtowers. Grizedale Hall was a converted stately home and was, according to reports, both luxurious accommodation and very expensive to run. Colonel Josiah Wedgwood (1872–1943), in a statement to the House of Commons, commented: ‘… would it not be cheaper to hold them [German POWs] at the Ritz Hotel in London?’

Camp 2 was situated at Glen Mill, Wellyhole Street, Oldham in Lancashire. This was a base camp for other ranks (ORs) and was described as being ‘a large cotton mill with its associated weaving huts’. It was later expanded with the addition of a number of Nissen huts.

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill became prime minister of the UK following the resignation of Neville Chamberlain on 10 May 1940. At this time Britain stood alone in its active opposition to Adolf Hitler and the German Nazi Party. History records that it was Winston Churchill’s resolve in these dark days that inspired the British people in resisting the German threat and standing firm against the enemy onslaught that was to follow.

The early days of the war saw very little need for any extended plans to build POW camps in Britain. Winston Churchill was most reluctant to house POWs in Britain in these early days of the war and, as a result, most were immediately dispatched to Canada and other Commonwealth countries. Britain might well be invaded by the German Army and it was felt unwise to hold a potential standing army of enemy troops within POW compounds.

The movement of German POWs and their Axis partners by ship provoked some very violent demonstrations; they were afraid, and rightly so, that they might be sunk by their own U-boats whilst in convoy across the Atlantic Ocean. Questions were asked in the House of Commons over the legality of taking such a risk under the terms of the Geneva Convention but eventually consent was given to their removal on the grounds of national security.

The Geneva Convention, whilst having no legal safeguards, did provide a framework of rules and expectations on how a prisoner of war was to be treated. The Convention generally worked well because much of a nation’s compliance relied on other nations’ reciprocity; it was signed by Britain, America, Italy and Germany but not by Russia. The Swiss government, as a neutral nation, provided the inspectors that would keep records of the treatment and facilities faced by the prisoners; this group was known as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

The author has relied a great deal on these reports to give a picture of the POW camps within the county of Gloucestershire. One of the key features of the Geneva Convention, made evident in the camp reports presented here, is the neutral status of the military medical personnel, allowing them to be known as protected personnel. These protected personnel were generally of the rank of officer, in charge of the day-to-day running of the POW camp and given much greater freedom of movement than other POWs. The second point the reader should be aware of is that ‘other ranking’ prisoners could carry out paid work but it could not be directly connected to any war-related operations. Each camp held a copy of the Convention printed in the appropriate language.2

The German Government did appeal to the British authorities to reveal the location of POW camps, so that they did not accidentally bomb them, but their request was refused and they were never given this information. It transpired after the war that the German Government had significant knowledge from several aerial reconnaissance photographs they possessed, many of which included the location of POW camps.3

ITALY JOINS THE AXIS

Benito Mussolini, against the advice of his ministers, took Italy into the war on 10 June 1940 and thus became part of the Axis with Germany and her partners. History records that the reason Mussolini and his Fascists decided to go to war was to gain territory through Algiers and Greece, and then to confront the British colonies in her bases in North and East Africa where the Italian and British Imperial territories often shared a common border.4

The Italian Army, striking from Abyssinia, mounted raids into Sudan, Kenya and Somaliland with some 91,000 Italian troops and an additional 182,000 from their African territories. They made great advances, including inroads into British Egypt, before their fortunes took a turn for the worse.

In December 1940, what was for the Allies to be a small exploratory raid by 7th Australian Division supported by British forces, codenamed Operation Compass, turned into a full-scale rout. In just a few days, over 38,000 Italians were captured. As if this were not enough, the 13th British Corps then encircled the retreating Italian 10th Army, taking a further 25,000 prisoners. As the British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, was reported as saying: ‘Never has so much been surrendered by so many to so few.’ This first influx of Italian POWs created a big logistical problem for the British Government.5

In 1941, Germany formed its ‘Africa Corps’ under Field Marshal Erwin Johannes Eugen Rommel (1891–1944). He was well respected by his men and treated all Allied prisoners under the terms of the Geneva Convention. The Italian Army was very poorly led and the German Africa Corps was sent to bolster up the Italian campaign and to get them out of the mess they found themselves in. By August 1941, however, there were well over 200,000 Italian prisoners.

America declared war on Japan on 8 December 1941 and Hitler then declared war on the US on 11 December, due to Germany’s treaty with Japan. American forces joined the British in invading French North Africa in an operation codenamed Operation Torch on 8 November 1942, which again resulted in a significant number of Axis POWs.

With America joining the push into southern Italy it was not long before Marshal Badoglio, who had seen the overthrow of Benito Mussolini’s Fascist government, surrendered on 8 September 1943. One report states: ‘They were all too willing to surrender to the British troops.’

With so many captured it became essential to build suitable camps to house them. At the start of the North African campaign, Operation Torch, most captives were sent to camps in South Africa and other African British dependencies such as Uganda, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Kenya and Tanganyika. In addition some were sent as far away as Australia, Canada and India. Initially this was for logistical reasons in an effort to reduce the cost of feeding such high numbers. It should be remembered that there were 130,000 Germans taken prisoner after the surrender of Tunisia on 13 May 1943.6

Holding German POWs in Britain was still a state of affairs that many feared, especially as German invasion remained a great threat and real possibility, but there was also a growing need for labour as more and more people enlisted into the armed services. German POWs were quickly transported to Canada and later, after America joined the war, to the USA.

The armed services had helped in Britain with the annual harvest but they were now required for war duties. With some reluctance it was decided, after much persuasion from the Ministry of Agriculture & Fisheries, that the Italians should be used to fulfil this labour shortage. The officers, however, who did not have to work under the terms of the Geneva Convention (1929), were sent to camps in India and other Commonwealth countries.

It is perhaps necessary to look at the stereotypical view of the Italian POWs as poor peasant types who avoided work, based not on facts but on the prejudices of the 1940s. Italians generally were seen as a docile labour force who could be used to fill labour vacancies in accordance with the Geneva Convention, and it was with this attitude that the records now show that there was a great reluctance to repatriate captives after their countries had surrendered.

The truth of the matter was that the Italians were just as effective in combat as any other soldier but it is also true that they were poorly led, poorly equipped, and many were conscripted and reluctant to join their Fascist leaders. It was only after the defeat of Germany had allowed German POWs and others to replace them as a labour force that the Italians were eventually repatriated. (See Chapter 5)

Taking that Italy surrendered in 1943, there were to be 157,000 Italian captives sent to Britain during this stage of the war. With such vast numbers it is interesting to note that there were to be 666 POW camps in the USA and twenty-one in Canada before the war was over. The largest Italian camp was at Zonderwater in South Africa, which was so vast that it has been described as the size of a city; it was the largest Italian POW camp, holding nearly 100,000 prisoners of war before it eventually closed down on 1 January 1947.7

This early victory in North Africa produced 50,000 prisoners to be housed in Britain, 3,000 to be sent by 8 July 1941 in order to help build the POW camps to house these new prisoners. One of the reasons Churchill had decided to accept them was the extreme shortage of labour. Two camps were prepared as transit camps: one at Prees Heath, Shropshire (Camp 16), and another at Lodge Moor in Yorkshire (Camp 17).

The accounts about these prisoners refer to their very poor state of health and that they were commonly lousy. The Minister of Health was concerned for public safety regarding prevalent infectious diseases including malaria, typhoid and dysentery, not to mention the infestation of body and hair lice.

Seven more labour camps were then built, the nearest to Gloucestershire being Camp 27 at Ledbury in Herefordshire.

THE GERMANS ARRIVE ‘EN MASSE’

Germany surrendered on 7 May 1945 and most German and other Axis POWs thought that they would be repatriated back to their homes in Europe, but this was not to be. Britain was desperate for labour after the war and with no further hold over the Italian POWs, now repatriated, the Germans were seen as an ideal replacement to fill this labour shortfall.8 Some of the German POWs were held in Gloucester until the final camp closed on 28 March 1948. Those that were seen as essential labour in rebuilding Germany were more fortunate in acquiring earlier release to civilian status.

On 5 July 1945, Churchill lost the general election and Clement Attlee became the new Labour prime minister of Britain. Attlee made it clear to all the Axis partners that POWs were to help rebuild Britain, as it was their countrymen who had caused the destruction in the first place. Such was the need to rebuild Britain that Germans and others were also transported back to Britain from holding camps in Canada and the USA, as well as Belgium and other European countries. There are several accounts of German personnel being told in America that they were being repatriated home, only to find themselves arriving at the port in Liverpool. POWs were immediately put on trains to various parts of Britain, where some found themselves arriving at Moreton-in-Marsh, Gloucestershire.9

Following the Allied invasion of Europe in 1944 a large number of German POWs arrived from holding camps in France, Italy and Belgium. On arrival at British ports they, like the Italians before them, were firstly deloused and then taken by train to one of nine ‘command cages’. Here the prisoners would be interrogated by army specialist officers, some of whom were Polish and fluent in the German language. Those considered to hold more important information were sent to special interrogation units where a number of methods were used to extract the information via hidden microphones, sleep deprivation or undercover informers.

One important task in this interrogation was to establish the degree of loyalty the prisoner had for the Nazi regime. The POWs were then graded as to their Nazi sympathies and issued with a coloured patch that was to be worn on their uniform: white or category ‘A’ for those with little loyalty to National Socialism and not seen as a security threat; grey or category ‘B’ for those that had no great feelings either way; and finally black or category ‘C’ for supporters of the Nazi philosophy or members of the Waffen SS. Efforts were made, sometimes without success, to keep the ardent followers apart from those that had no strong political views.

THE POW CAMPS OF GLOUCESTERSHIRE

The POW camps within the county developed primarily with the compulsory requisition by the War Office of land on which to build them, or the re-use of existing army and air force accommodation. Some large properties were also requisitioned such as Quedgeley Court, Swindon Manor Estate and Leckhampton Court.

America entered the war in December 1941 and many new army camps were built to accommodate the vast number of American ‘GIs’ arriving in the UK. Gloucestershire received many thousands of these troops in places such as Tewkesbury, Daglingworth, Cheltenham and the north Cotswolds, and all these troops and support staff had to be housed. Many logistical bases were set up in preparation for the D-Day landings on 6 June 1944, with units based in and around Moreton-in-Marsh, Blockley and Northwick Park. Some of these camps were later utilised as POW camps, after being vacated by the American forces.

In addition to the ‘GI’ accommodation, the Americans also built military hospitals in and around Gloucestershire, with one at Northwick Park eventually being re-designated by the International Red Cross as a hospital for German casualties only.

Other smaller hostels were built by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries & Food just prior to the war in order to accommodate agricultural workers, but they were used instead to house small numbers of POWs. Some of these hostels were greatly enlarged.

The Geneva Convention allowed for the POWs to undertake work of a non-military nature only. Officers were exempt from working but other ranks were often grateful for work, reporting that it alleviated the boredom and waiting that was experienced during confinement in a POW camp. Prisoners would usually be detailed to do farm work, which would involve hedging, ditching and harvesting, or construction work. They were later employed at some RAF stations in the county. If working on farms, they would be under the direct command of the farmer by whom they were employed. POWs housed at farms were to have the same accommodation expected by a British soldier, such as a room, hot and cold water and a suitable bed. The prisoners undertaking this work received a wage initially paid into their account to spend at the camp shop.

After the German surrender, many Germans who had been tradesmen were used in the construction industry. The bombing campaign by the Germans meant that, after the war, there was a drastic housing crisis in Britain; it was estimated that some 4 million homes had been destroyed which would have to be replaced. Work and working conditions had generally to be approved by the trade unions, who were also concerned that troops returning to Britain and needing employment should be given priority.

Whilst work was essential in rebuilding Britain, the authorities quickly realised that Germany itself needed rebuilding – as well as re-educating away from the Nazi philosophy and towards a more democratic regime. Officers commanding prisoner-of-war camps were asked to appraise their captives to identify men who had provided essential services before the war, such as policemen, builders, miners etc. These men were given preferential treatment in repatriation.

2

Camp 37

Sudeley Castle, Winchcombe

Sudeley POW Camp 37 at Winchcombe SP 030 278, 9 May 1946.1

THE ITALIANS

Camp 37 was first visited by Mr R. Haccius on behalf of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) on 23 July 1942.2

This camp, like many others, was built by the Italian POWs whilst under guard by the British Pioneer Corps. The Italian prisoners arrived in Winchcombe by train and were then marched to the site of the new camp within the grounds of the Sudeley Castle estate. Some of the British Pioneer Corps were housed at No. 62 Northgate Street, Winchcombe.3

The name of the camp commandant is not recorded in the first few reports but the Italian camp leader was Sergeant Major Giuseppe Furlanetto. There were 553 Italian POWs housed in the camp: one medical officer and 552 warrant officers and soldiers. The original ICRC reports were written in French but they are very comprehensive and give a good idea about the daily life of the prisoners and the conditions of their confinement.

Camp 37 was described as an agricultural camp of very recent construction. It was situated in the grounds of Sudeley Castle, which had been requisitioned by the War Office. Its location was described as a quiet area surrounded by hills, near the village of Winchcombe and approximately 12 miles from Cheltenham, and the climate was reported as ‘healthy’.

The inspector found that the new huts were roomy and described them as of three types: Nissen, reinforced concrete and Tarrant huts. All were double walled and well insulated from the ground and each contained two air-heaters for warmth in winter. Three huts were reserved as meeting rooms and a dining room. The ration of coal in the camp was fixed at 20lb per man per day in summer and 56lb in winter, which was sufficient to maintain a suitable temperature in each hut. The maximum capacity of Camp 37 was set at 600 men, with each hut capable of housing up to forty prisoners. (There was, however, no mention that some POWs were still housed under canvas as the camp was not fully completed at this time.)

The interior installation consisted of bunk beds made out of wood with metal grids, straw mattresses or palliasses, and the prisoners were provided with three blankets in summer and four in winter. The lighting and ventilation was said to be sufficient and all the huts were lit by electricity. The provision of fire protection was applied according to the army regulations for such camps. From other camp reports this fire protection was usually two buckets of sand inside the hut and one bucket of water outside.

A local farmer recalls that there were problems constructing the water tower but that this was eventually overcome, resulting in adequate water at a suitable pressure for the sanitary facilities. There were twenty-four flushing toilets, and ten showers with a hot water supply, but this was found to be insufficient and further toilets and showers had to be constructed.

The rations complied with the recommendations of the Geneva Convention for POWs and they were inspected daily by the camp leader. The menu for the week was established by the chef and on the day of the ICRC visit was as follows:

Breakfast:

Milk, coffee, margarine, marmalade and bread

Lunch:

Soup, fried potatoes, greens and minced beef

Supper:

Soup, cooked bacon, bread, milk and coffee

The British authorities at this time did not understand the cultural differences in dietary requirements for their newly established prisoners, but after general complaints from this and other POW camps the diet was changed, as far as was possible, to a more continental diet. Whilst it is not mentioned for Camp 37, later reports from other camps in Gloucestershire stated that they had acquired a hut for making macaroni.

The British discovered that the Italians preferred more bread and less meat. They liked a loose loaf rather than the denser tinned loaf, vegetable soup and macaroni as much as possible. Quantity rather than quality. One War Office official requested that a more liberal diet of bread and vegetable soup be provided arguing that it would prove cheaper than the ‘depot diet’ laid down by the military authorities.4

The infirmary was installed in one of the Nissen huts and any POW in a serious condition was generally evacuated to the nearest civilian hospital. One case of tuberculosis was evacuated to a hospital in Oxford.

The POWs all wore their battledress, which was replaced or repaired by the camp tailors when necessary. The camp leader and the medical officer, both of whom were protected personnel, wore their full uniforms. Underclothing and toilet articles were given to each Italian POW on arrival in England at their reception camp. They each received one 112g bar of soap per week, which they considered to be an insufficient quantity.

The prisoners were paid for their work in accordance with the Geneva Convention, though officers did not have to work. The pay was 1s (5p) per day for the qualified workmen and 6d (2½p) per day for the labourers. The pay for warrant officers was 2s (10p) per week, and for warrant officers below the rank of adjutant and for regular soldiers the pay was regularly reviewed. Prisoners were not allowed to have actual money and would be disciplined if found to be in possession of any, but they were issued with tokens that could be exchanged for goods in the camp canteen. Other moneys earned were deposited in the prisoner’s personal account to be handed over when repatriated.

The working hours were limited to eight hours per day. The POWs were transported to their work either by the army authorities of the camp, or by the farmers themselves. It is recorded that 439 men were at work or otherwise occupied on the day of the ICRC visit:

253

doing agricultural work (lodging at the camp)

50

doing agricultural work (lodging at hostels)

19

doing agricultural work (lodging in billets on the farms)

117

foresters (lodging at the camp)

The remainder were occupied at work, servicing or running the camp.

The POWs enjoyed a large amount of liberty during their work. Those who were questioned during the inspection declared that they preferred the distraction that occupation brought to them rather than the otherwise monotonous life in the camp.

The inspector found that the canteen was well provisioned, and the profits were used for the purchase of books, plays, seeds, sheet music and articles for sport. The turnover for June 1942 reached £460. He noticed, when examining the accounts, that a collection had been made by the inhabitants of Winchcombe for the following Christmas. This had raised the sum of £2111s6d (£2158p) to improve the funds of the canteen.

Most of the Italian prisoners were Roman Catholics and a Catholic Mass was celebrated each week by Father Francis P. Ryan from Winchcombe. The diary of the Catholic bishop, the Rt Revd William Lee, indicated that he celebrated Mass with the prisoners on several occasions: once to conduct a Confirmation on 8 March 1943 and again to take Mass on Saturday, 17 April 1943.5 The local farmers going to church on a Sunday morning would take along any Italian POW who wanted to attend a church service.

This camp offered excellent recreation facilities for the prisoners to enjoy in their leisure time, including billiards, table tennis and boccia. Football was practised on Sundays on the sports field in Winchcombe. Soon the POWs were playing football against the guards, other nearby POW camps, and even the village football team.

The inspector reported that the POWs had built a theatre complete with lighting and stage accessories and, to judge from some of the programs they had recently performed, he thought the men displayed a lot of talent.

Courses of study and in particular the English language were organised by the POWs. The books regularly received from the International Red Cross gave them a lot of pleasure. The choice was good and the subjects were varied, though it must be realised that the books supplied were subject to censorship. Books of study and techniques concerning agriculture were requested by the prisoners. A radio was provided for them and speakers were placed as high as possible within the camp. Permission was given for them to listen to the Italian station and certain programmes from Radio Roma.

The mail from Italy arrived at regular intervals, with the letters taking approximately four weeks to reach their destination. The prisoners could send a letter and a card each week. Letters addressed to the delegation of the Committee of the International Red Cross, London, or to the Italian Red Cross, were not limited. Some packets were sent by the Italian Red Cross to the camp after two POWs, whose names had been sent to Geneva, complained that they had not received any news of their families.