Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

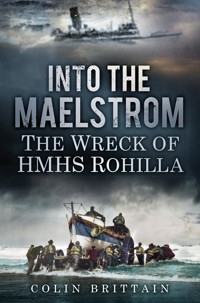

On 29 October 1914 the hospital ship Rohilla left Queensferry with 229 persons on board; the vessel was bound for Dunkirk on an errand of mercy, under wartime restrictions and in deteriorating weather. Just after 4 a.m. there was a tremendous impact as the ship ran on to rocks at Saltwick Nab, a mile south of Whitby. Rohilla was mortally wounded 600 yards from shore, 'so close to land yet so far from safety'. Over the ensuing days the heartrending loss of 92 lives in terrible circumstances would prove to be Whitby's greatest maritime disaster, still regarded as one of the worst amongst the annals of the RNLI. This book reveals the heroic actions of the public who waded out into icy turbulent waters to reach those who made the swim to shore and the gallant efforts of lifeboatmen forced to manhandle lifeboats over piers, rocks, overland and down a 200ft cliff.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 536

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to the memory of all those who suffered through the ordeal that befell His Majesty’s Hospital Ship Rohilla and its repercussions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would not have got this far had it not been for the support of The History Press and I cannot thank them enough for the help they have given me. In order to complete this book I have sought help from numerous sources. In the case of those affiliated to professional bodies, I am truly grateful for their patience in dealing with my constant questions and enquiries. I am eternally grateful to those who personally helped in my research and in the supply of material, as I am to anyone who has not been individually listed hereafter.

My grateful appreciation goes to close acquaintances and descendants of those lost on the Rohilla: Elsie Naylor, Jan Green, Edna Chadwick, Hilda Elsworth and Rodney Birtwistle. I offer my grateful thanks to Sarah Turner, Ron Dunn and the late John Littleford for the many long hours they spent with the ‘lead’ to supply the images required to effectively illustrate this book. I am grateful to Paul Hutchinson for his remarkable coloured illustration of Dr Ernest Lomas.

I wish to offer my thanks to the following people who contributed in their own way to the publication of this book:

Alan Holmes – for his assistance with grammatical proofing; Alan Wastell – for sharing his time and expertise to assist me with numerous photographs; Barbara and the rest of the staff at Whitby Library for help in obtaining information from the many microfiche files; A. Vicary – for allowing the use of pictures from his extensive collection held at the Maritime Photo Library; Barry Cox – for allowing me to reproduce illustrations from his book; Ben Dean – for supplying information and illustrations as an ex-owner of the wreck; the late Catherine Smith – for allowing me the use of her postcards, which covered the funeral processions; Charles Collier Wright – for allowing me to use extracts from Mirror Group Newspapers; Colin Starkey – one of the many valuable staff at the National Maritime Museum; David Stephens – for allowing me to rummage through his collection of underwater images; Duncan Atkins – for his assistance in searching through the many original newspapers at the old Whitby Gazette offices; Ian Wright – for his picture of the Deadmans Fingers; Jeff Morris – for allowing information from his booklet; Jim Grant – a helpful librarian at the Scottish Maritime Museum; Joyce D. Richmond – for permitting the use of images related to W. Knaggs and wonderful information on Whitby St John Ambulance Brigade; Ken Wilson – for giving me consent to use extracts and illustrations from his book, and to his widow Sheila for her continued support; Lorraine Cunningham – a respected member of staff at Harland and Wolff Technical Services Ltd, who scoured through endless archives in search of missing technical drawings; Lynn Everington – from TheYorkshire Journal, who helped secure extracts from the publication; members of Whitby lifeboat station – who allowed me access to the original lifeboat records; Mike Shaw for allowing use of a treasured image from the Frank Meadow Sutcliffe Gallery; Mr Smith for supplying information from World Ship Society records; Peter Barron who gladly gave permission to use extracts from the Northern Echo; Peter Thompson Hon. Curator Whitby Lifeboat Museum whose help with lifeboat photographs was appreciated; Stephen Rabson – P&O historian and archivist who gave me permission to use BISNC logos; Stuart Norse and Brian Wead – who gave me information in their capacity as RNLI Service Information Managers; T. Kenneth Anderson for his help in retrieving record information from files at Ulster Folk and Transport Museum; the enthusiastic volunteers at the Whitby Archives Trust who gave me unrestricted access to their files, which are sadly no longer available; the willing staff members of the British Newspaper Library for obtaining copies of papers which covered the tragedy; Andre Dominguez for his input and name correction for the MacNaughton brothers.

Andrew McCall Smith, a great nephew of Arthur Shepherd who shared with me a host of valuable family information; Arthur Walsh, grandson of William Farquharson; the late Chris Lambert, for his background information on Major Herbert Edgar Burton GC OBE; Colin Berwick and John Timmins, for their help and advice regarding the Kingham Hill School tragedy; Wendy and Lewis Breckon, who, as relatives of George Peart, were really helpful and Daniel Peart, for his wonderful history of George Peart; David J. Mitchell, an ex-British India Engineer who shared his expert knowledge of the BISNC; Ian Morris, for his London Pageant photographic work; Jim Barnett, a retired sub aqua diver who has dived the Rohilla and whose cuttings were helpful to me; John Cummins, for detailing Thomas Cummins’ exploits as the motor mechanic on the Henry Vernon; John Mules, for his most valuable help regarding Nursing Sister Mary Louisa Hocking; John Stephenson, a descendant of George Brain; John Todd, a descendant of John Bleakley; John Wilson, a grandson of Frederick Edwin Wilson, Junior Marconi Operator; Mr Pickles, Photographic Curator, Whitby Museum, Pannett Park; Ray and Mandy Harvey, Fiona Kilbane, and Katherine Pennock for providing detailed information on Mary Keziah Roberts and her family; Simon Lowes, whose grandfather, Ernest Parker, was a cabin boy (Ernest and his brother, William, both survived the tragedy); Terry Offord, whose mother sailed on the Rohilla when she was a troopship; William McClure, the present owner of the wreck, who supplied information, photographs and his valuable insights; Anne Poole, for deciphering many of the fine handwritten papers I have acquired about the Rohilla; Margaret Whitworth, a loyal lifeboat supporter and keen photographer; Betty Bayliss, for sharing her passion for the Whitby division of the St John Ambulance Brigade; Betty Sayer, for her guidance as to the background of Alexander Corpse; Dorothy Brownlee, whose grandfather James Brownlee was the 2nd coxswain of the Tynemouth motor lifeboat Henry Vernon, and who has proved to be a trusted confidante and friend; Geraldine Bullock, for her help with information on Harry Claude Robbins; Julie Diana Smith, whose husband’s great-great-great-grandfather was Coxswain Robert Smith and was a mine of information (no pun intended); Heather Sheldrick, one half of the folk duo Bernulf and composer of a song about the loss of the Rohilla; Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society, Whitby Museum, Pannett Park.

Thanks to the Royal National Lifeboat Institution for allowing me the use of selected photographs including those from Nigel Millard, David Ham, Nathan Williams and the collection of the late Graham Farr.

Thank you to all those who have contributed to this second edition, your help has proven priceless.

All images are copyright of the author unless stated otherwise.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Author’s Preface

1. Allied Hospital Ships of the First World War

2. The Beginning

3. The Barnoldswick Connection

4. The Rescue Begins to Unfold

5. The Funeral Ceremonies

6. The Inquest Procedures

7. The Repercussions of the Rohilla Disaster

8. Anniversaries and Commemorations

9. Exploring the Wreck of the Rohilla

10. RNLI Coxswains and Crew

11. The William Riley of Birmingham and Leamington

12. The Tynemouth Motor Lifeboat Henry Vernon

Appendix I Fleet Surgeon Ernest Courtney Lomas

Appendix II Nursing Sister Mary L. Hocking

Appendix III Mary Kezia Roberts

Appendix IV Survivors and Hosts

Bibliography

Copyright

FOREWORD

The British India Steam Navigation Company

Aboard the Cape of Good Hope the British India Steam Navigation Company carried six companies of the 37th Regiment of Foot (to become the 1st Battalion, The Royal Hampshire Regiment) from Colombo to reinforce the Calcutta garrison in June 1857. So began a history of service to Empire and country which only came to an end with Uganda’s involvement in The Falklands Campaign in 1982 and subsequent charters to the Ministry of Defence until 1985.

Between those years in times of war and peace, the BISNC provision of regular and casual troop transports, ambulance and hospital ships was unsurpassed by any other company. Prior to the First World War, ships carried troops to and from twenty-five campaigns and theatres of war, during which the BISNC fleet had grown to 126 ships. After a decision made in the early 1890s not to carry troops in Royal Navy vessels, regular chartering commenced and post-Boer War charters included Rewa, Jelunga, Dilwara, Dunera and Rohilla. Taken into war service as a hospital ship on 4 August 1914, the latter’s career was destined to be only a few weeks long before being wrecked on Saltwick Nab.

Colin has chronicled this event after years of tenacious research into all its aspects, leaving no stone unturned and, indeed, information is still coming to light to record the feats of six lifeboat crews and the succour given by the citizens of Whitby to the survivors, and I am very pleased to contribute to this record of tragedy and heroism.

David J. Mitchell

Engineer Officer 1967–74

British India Steam Navigation Company

AUTHOR’S PREFACE

I have always felt an affinity for the sea, enthralling as it is majestic, and capable of delivering such ferocious power that it can literally break a ship’s back, sending it to the bottom. As a child growing up I wanted to be a diver. Today we are spoilt with a wealth of programmes devoted to the undersea world, but to get the sort of warm clear water to dive wearing no hood or gloves and a thin suit means travelling to some exotic destination. I learned to dive in 1985 and recall only too vividly my first open-water dive into Jackson coal dock, which was later filled in and now forms part of Hartlepool Marina. Underwater visibility in this inky black water was 2ft at best and all I could do was follow a buddy line to my dive partner. It was so far removed from anything I had ever seen on television that I wonder how on earth I carried on. Over the years I enjoyed a varied and challenging diving career. When three brain tumours forced me to ‘hang up my fins’, I was devastated for scuba diving had become part of our family way of life. As an open-water instructor I enjoyed teaching as much as I did being part of a small group of experienced dedicated divers. Having always enjoyed wreck diving, I decided to try and use my existing knowledge and experiences as the basis for a new direction. My first book, Scuba Diving, was published in 1999; a dedicated diver training manual followed in 2001, and then I started a book which would take far more of a grip on me than I could ever have imagined, a book that has truthfully seen me through some very dark and painful times.

One of my favourite wrecks, on which I enjoyed many a dive, was that of HMHS Rohilla. This large liner was requisitioned as a hospital ship and lost in tragic circumstances at the start of the First World War. During a relatively quiet period I began to write what was initially going to be a short guide to the circumstances surrounding the awful loss of this vessel. But, as I gathered information, it soon became apparent that there was much more to the story than I first envisaged. I felt that I could not do it justice by just writing a simple guide, and my work soon blossomed into a full-fledged manuscript.

The first edition of this book was published in 2002 and since then I have never stopped researching the subject. Often, finding the smallest of references can lead one down a new path. I was exceptionally pleased with the first edition, but since then so much new information has come to light, quite a bit of it from descendants of those who were part of the tragedy in 1914. I am indebted to my publisher for allowing me the opportunity to revise this book.

It is my intention in this second edition to share with you some of the wonderful new information and unreleased photographs, and present a more detailed explanation of how the tragedy unfolded over the course of a weekend. Some past conclusions will be ruled out and assumptions will be found to have a basis in fact. For many years it has been accepted that those who perished numbered eighty-four or eighty-five, but, working with a family descendant, I feel confident enough to reveal that the figure is actually higher than eighty-five.

I have thoroughly enjoyed learning more of the personal history of some of those involved, and been saddened when reading individual accounts given by survivors. With today’s advances in social networking and the internet, it is easier to ‘talk’ with people and in many cases this has been mutually beneficial. I can honestly say that, from the very outset of writing the first edition, I have felt honoured to be able to engage with descendants of those who survived or perished, and to share their stories.

I am sometimes asked for contact details for people with whom I have shared letters, emails and telephone calls. However, out of respect I would not reveal such delicate information; the relatives of anyone involved in the Rohilla’s loss need to know they can trust me, especially as some are approaching their wiser years. This may not sit well with some, but then this is not just a pastime for me. If I can help bring two parties together I will, but I won’t jeopardise my close relationships with my sources.

In researching and writing this new edition I have included many fine and honourable statements that pay respect to the lifeboat service as it was in 1914, but which apply equally well today. Behind the brave men and women that man our lifeboats, there is a network of thousands who work away in the background supporting the RNLI, incorporating both professional and volunteer sectors. It has to be said that those doing what they can to support the Institution, be it those who man the many retail outlets or the thousands of ordinary people willing to volunteer their time fundraising in whatever capacity they can are as equally important.

Brian Dobie presenting me with the illustration of the Rohilla that his son Neil drew for me.

I was pleasantly surprised to receive a large hand-drawn illustration of the Rohilla. Well, maybe surprise isn’t quite the word I am looking for as I knew the artist was doing something special for me. I just wasn’t told what. The artist, Neil Dobie, gets his talent from his mother, who is extremely proficient in all things ceramic and has her own kiln, but what makes this lady special to me is her name – Mrs Rohilla Dobie. I was presented with the wonderful illustration by Rohilla’s husband Brian, whom I had only ever spoken to in the past. It must have taken Neil quite a while to complete this illustration and I am really glad to have it.

When working with a story that is very nearly reaching its centenary, some omissions or errors are inevitable. However, every effort has been made to reduce the number of inaccuracies. I would be happy to hear of any amendments or further information that could be used to update my research or be added to subsequent editions of this book.

1

ALLIED HOSPITAL SHIPS OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR

Hospital ships were primarily large liners fitted out with the necessary facilities to serve as an efficient hospital. They were registered with the Red Cross and equipped to deal with most cases of injury and disease, and to transport the wounded back to Britain for more specialist treatment or recuperation. They were equipped wholly or in part by private individuals or by officially recognised societies. In 1907 the Hague Conference laid down conditions under which hospital ships would be accorded immunity from attack. In order to be easily distinguished, vessels assigned as hospital ships were given a unique colour scheme: their hulls and superstructure were painted white, a green band ran round the hull parallel to the waterline, broken to fore and aft by a large red cross. As well as flying their national flag, hospital ships displayed the flag of the International Red Cross. To ensure that they were distinguishable at night, the hulls were brilliantly illuminated with long rows of red and green lights along the sides. Identified in this way, it was reasoned that they would be protected from attack under the Geneva Convention; sadly, however, in practice this was not always the case.

The Red Cross insignia, red arms of equal length on a white background, was accepted as the emblem of mercy, and is in fact the Swiss flag with its colours reversed, recognising the historic connection between Switzerland and the original Geneva Convention of 1864. The insignia has two distinct purposes:

• to protect the sick and wounded in war, and those authorised to care for them

• to indicate that the person or object on which the emblem is displayed is connected with the International Red Cross

The emblem was intended to signify absolute neutrality and impartiality; its unauthorised use was forbidden in international and national law.

When the insignia was accepted as the design for the Red Cross, one shipping company, Rowland & Marwood based in Whitby, was required to change its company logo, which until then had been a red cross on a white background, with a blue border. To avoid confusion with the Red Cross, they redesigned their logo by swapping the blue and red around.

Altogether, seventy-seven military hospital ships and transports were commissioned during the First World War: twenty-two in 1914, forty-two in 1915, seven in 1916 and six in 1917. Among this number were four Belgian government mail steamers: the Jan Breydel, Pieter de Connick, Stad Antwerpen and Ville de Lire. Five yachts were used for the transport of patients.

Among the vessels used were three of the giant liners of the period. The Aquitania, built for Cunard by John Brown & Co., had the greatest accommodation with 4,182 beds. The Aquitania was launched in 1913 and, after her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York, begun on 30 May 1914, she made only two more Atlantic crossings before the First World War began. The vessel completed just over two years’ service as a hospital ship from 4 September 1915 to 27 December 1917. On one journey from the Dardanelles she had almost 5,000 patients on board, and twenty ambulance trains were needed to dispatch them from Southampton to various hospitals across Britain.

During the war Aquitania served as a hospital ship, an armed merchant cruiser and a troop transport, returning to commercial service in June 1919. Later that year she was taken out of service for refitting and conversion from coal to oil. When the Second World War began, she was again called into service as a troop transport, one of a small number of ships to serve in both World Wars. In 1948–49 Aquitania was placed on a Southampton to Halifax austerity route, and her last transatlantic crossing was from Halifax to Southampton. After making 443 transatlantic roundtrips, steaming over 3 million miles and carrying almost 1.2 million passengers over a thirty-five year career, Aquitania was scrapped in 1950 at Faslane on the Gareloch.

HMHS Britannic was the biggest of the three Olympic-class ships (Olympic, Titanic and Britannic). The Britannic had the second largest accommodation for patients, being capable of holding over 3,000, and was in service for just over a year from 13 November 1915. When the Titanic was lost in April 1912, the building of Britannic had just started, allowing modifications to be made to improve the vessel’s safety.

The Britannic was launched on 26 February 1914 and was requisitioned as a hospital ship when the First World War began. At around 8 a.m. on Tuesday 22 November 1916, Britannic was steaming in the Aegean Sea when she was rocked by an explosion. As the ship began to list, Captain Charles A. Bartlett tried desperately to steer her towards shallower water. Despite the modifications made in construction, the Britannic sank in just fifty-five minutes, miraculously taking with her only thirty people out of the 1,100 reported to have been aboard. The Britannic was located in 1976 by Jacques Cousteau resting at a depth of 100m. An expedition was made in October–November 1997, during which a memorial plate was laid on the wreck.

Built for the Cunard Line by Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson, Wallsend-on-Tyne, Mauretania measured 762ft x 88ft. Her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York was made on 16 November 1907. Although severe storms and heavy fog hampered this first voyage, the ship still arrived in New York in good time on 22 November, no doubt aided by her service speed of 25 knots. A later refit saw a change of inner shafts and a move to four-bladed propellers. By April 1909 the Mauretania had made both westbound and eastbound records, retaining the Blue Riband Trophy for twenty years. At the end of 1909, the ship’s first captain, John T. Pritchard, retired and Captain William Turner assumed command. The Mauretania’s reputation attracted several prominent passengers, including HRH Prince Albert (later George VI) and Mr Carlisle, the managing director of Harland and Wolff. In June 1911 the ship brought thousands of visitors to Britain for the coronation of George V.

When Britain declared war on Germany, the Admiralty sent out an order requisitioning the ship as soon as it returned to Liverpool. On 11 August, however, the Mauretania was released from government duties. After the loss of the Lusitania, the Mauretania was required to return to service. At the end of August 1915, she returned to Liverpool, where she was fitted out as a hospital ship offering room for nearly 2,000 patients. She then left Liverpool in October to assist with the evacuation of the wounded from Gallipoli. The Mauretania made several further voyages as a hospital ship and completed her last on 25 January 1916.

The liner had a chequered career, undergoing numerous calls to service and refits before making her final passenger sailing from Southampton on 30 June 1934 – the day the Cunard and White Star Lines merged. The completion of the Queen Mary meant that the Mauretania was now outdated. After a lay-up the liner was sold to Metal Industries Ltd of Glasgow for scrap, with her fixtures and fittings auctioned on 14 May 1935 at Southampton Docks. The Mauretania reached the Firth of Forth on 3 July and was moved to Rosyth for dismantling.

In operations against German-occupied Namibia, the hospital transport City of Athens and hospital ship Ebani were used, the latter serviced by the South African Red Cross Society. In an emergency the Ebani could carry 500 patients. She was staffed by South African Medical Corps personnel and on the termination of the campaign was handed over to the Imperial authorities.

Even when the enemy obeyed the Geneva Convention, the white hospital ships still faced hazards. In the years 1914–17 seven military hospital ships struck mines and were either sunk or badly damaged. In 1917 the Central Powers decided to disregard international law, and hospital ships, no matter how prominently marked, were no longer given their due protection. In 1917 and 1918 eight hospital ships were torpedoed and the resulting casualties were indeed tragic.

HMHS Asturias

Built:

Harland and Wolff, Belfast.

Tonnage:

12,105 gross, 7,509 net.

Engine:

Twin screw, quadruple expansion; 2 x 4 cylinders; three double- and four single-ended boilers.

Cruising Speed:

16 knots.

Steel Hull:

Two decks, five holds, with ten hydraulic cranes.

Passenger Capacity:

300 First Class, 140 Second Class, 1,200 Steerage.

The Asturias was the first RN vessel to be fitted with a passenger lift. Forecastle and bridge 447ft (136.25m); poop 52ft (15.85m).

History

1906:

Keel laid down, the fifth of the ‘A’ class ships for the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company.

1907:

Launched.

1908:

Maiden voyage from London–Brisbane, then transferred to Southampton–River Plate service.

1914:

Requisitioned for use as a hospital ship.

1917:

Torpedoed at Bolt Head off the Devon coast, whilst in full hospital colours, with the loss of thirty-five lives.

1919:

Purchased by Royal Mail before once again being laid up at Belfast.

1923:

At the end of a two-year rebuild at Harland and Wolff, emerged as the cruise liner Arcadian.

1930:

Laid up in Southampton Water.

1933:

Sold to Japan for scrapping.

HMHS Rewa

Built:

William Denny & Brothers, Dumbarton (Yard No. 762).

Tonnage:

7,267 gross, 3,974 net.

Classification:

Passenger Cargo Ship.

Engines:

Triple screws with Compound Parson’s turbines, two double- and four single-ended tube boilers operating at 152 psi.

Coal Capacity:

1,506 tons.

Estimated Speed:

16 knots. During trials she managed just over 18 knots.

Steel Hull:

Three decks.

Build Description:

Five holds, eight watertight bulkheads, two hydraulic cranes to each hatch, with main and lower decks lighted and ventilated, ensuring suitability for trooping.

History

1905:

Launched for British India Steam Navigation Co. Sister of SS Rohilla.

1905:

Delivered to London. Cost £159,680.

1905:

Maiden voyage to India. First turbine steamer on the route.

1905:

The vessel became a permanent trooper during the season.

1910:

Carried the members of the House of Commons to the Coronation Naval Review at Spithead.

1914:

Became Hospital Ship No. 5 equipped with eighty doctors and 207 nurses.

1915:

Detailed for Gallipoli.

1915:

Left Gallipoli with wounded soldiers.

1918:

While steaming fully illuminated in the Bristol Channel, and carrying 279 wounded from Greece, the ship was torpedoed.

The hit was amidships, mortally wounding the vessel. All the lifeboats were successfully launched, ensuring the escape of those on board, with the exception of three people killed in the initial explosion. The captain had only minutes earlier warned that the alert should be maintained until she docked: ‘It isn’t over until we berth.’ It is highly likely that this vigilance conttributed to the remarkable survival record of those who were later landed at Swansea.

HMHS Rewa, a sister ship to the Rohilla.

2

THE BEGINNING

Ship number 381 was launched at the Harland and Wolff shipyard, Belfast, on 6 September 1906. She was delivered to her owners, the British India Steam Navigation Co. Ltd, on 17 November 1906, and named SS Rohilla.

Formed in 1856 to carry mail, the Calcutta & Burma Steam Navigation Co. operated until 1862, when, after raising more capital in the UK, it became the British India Steam Navigation Co. Ltd. Operating ships ranging from small service craft and tugs to major vessels both passenger and cargo, between its founding and 1972 the company owned more than 500 vessels. The British India Steam Navigation Co. retained its separate identity after amalgamation with the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Co. (P&O) in 1914, with P&O operating as the parent company, but in 1971 P&O was reorganised into divisions: general cargo, passenger and bulk handling. All ships were progressively transferred to one of these divisions, resulting in the loss of all those individual shipping company names which made up the P&O group. Relatively unknown in the UK, British India had the largest number of ships flagged under the Red Ensign at any one time, reaching 161 in 1920.

Carrying passengers from the beginning, many ships were only 500 tons or so, plying their trade on coastal services round India or from India to Burma, East Africa and around the Persian Gulf. Such was the expansion in trade that within less than twenty years ships on order exceeded 2,000 tons each.

With few exceptions, ships under the control of British India used names which were derived from, or based on, Indian place names, and those places which ended in the letter ‘A’. The SS Rohilla was no exception to this practice, being named after an Afghan tribe who had entered India in the eighteenth century during the decline of the Mughal Empire, gaining control of Rohilkhand (formerly Katehr, United Provinces, east of Delhi)

The British India Steam Navigation Company logo.

The British India Steam Navigation Co. operated fortnightly voyages from London to Colombo, Madras and Calcutta. The Rohilla was built as a passenger cruise liner and registered at Glasgow. After her completion, the Rohilla entered the London to India service, operating from Southampton to Karachi. Those who travelled on the Rohilla when she was still a cruise ship remarked on the opulence and attention to detail. The varierty of meals offered on the Rohilla were carefully thought out ensuring that the high standards passengers had come to expect whilst cruising were maintained throughout.

Dinner

Consomme Andalouse Creme Marie Stuart

Fillet of Telapia Sauce

Tartare Bra’sed Sheep’s Hearts

Chasseur

Gombos Lyonnaise Leg and Shoulder of Pork

Apple Sauce

Vegetables

Brussel Sprouts Browned and Boiled Potatoes

White Wine

Cold Buffet

Consomme Froid

Roast Beef Galantine of Chicken

Salad in Season

Wines

The undermentioned wines are ready for serving with this meal

White Wine

Witzenberg Hock HALF BOTTLE 61-

Red Wine

Alphen Burgundy HALF BOTTLE 61-

The Wine List showing a full list of wines in stock may be obtained from the Wine Stewards

Sweets

Lemon Bavarois

Coupe Bresilienne

OFFICIALLY HELD INFORMATION (LLOYDS REGISTER)

British India White Tailed Kingfisher menu.

Number in Book:

685

Official Number:

124149

Code Letters:

HJQK

Name:

ROHILLA

Material / Rig:

Steel / Twin Screw Steamer

Master:

Captain David Landles Neilson

No. of Decks:

Three decks, mild steel, part teak with eight watertight bulkheads.

Special Surveys:

Electrical, Light Wireless.

Registered Tonnage:

7,409 tons

Gross:

5,588 tons

PARTICULARS OF CLASSIFICATION

Special Survey:

January 1910

Port of Survey:

Southampton

Built:

1906

Builder:

Harland and Wolff Ltd, Belfast

Owner:

British India Steam Navigation Co. Ltd

REGISTERED DIMENSIONS

Length:

460ft 3in

Breadth:

56ft 3in

Depth:

30ft 6in

Port of Registry:

Glasgow

Flag:

British

ENGINES

Cylinders and Diameter:

Quadruple eight-cylinder engines – 27in, 38.5in, 55.5in, 80in

Stroke:

54in

Boiler Pressure:

HS21894

Horse Power:

1,484hp

Boilers and Furnaces:

3D & 35B, 27cf, G5527, FD

Engine Maker:

Harland and Wolff Ltd, Belfast

The Rohilla was well equipped, fitted with the latest Marconi wireless telegraphy, and capable of a top speed of 17 knots. In general, British India ships prior to 1955 shared the same livery, having a black hull with a single white band, and a black funnel with the company’s distinctive two white rings, whilst ships after 1955 were painted with white hulls with a black band painted around the topsides. The Rohilla, like many British India ships, experienced multiple colour changes during her service, depending on the service operated.

HMT Rohilla in port, embarking troops.

Captain David Landles Neilson was given command of the Rohilla from the outset. Neilson was born in Tranent, East Lothian, in 1864 and had worked hard throughout his career, qualifying as a 2nd mate when only 18 years old; he was awarded a Master Mariner’s Certificate when he was 34. He is recorded as having served aboard the Dwarka in 1904 and the Sofala in 1906, and spent his whole career with the British India Steam Navigation Co.

In 1908 the Rohilla joined her sister ship, the SS Rewa, as a troop ship. It would appear that during her troopship service the Rohilla was allocated several different numbers. She was initially designated HMT Rohilla No. 6, but extant illustrations only show the Rohilla bearing the numbers 1, 2, 4 and 6; the numbers signified the route she was operating.

It was expected that, as a troopship in 1908, the Rohilla would have operated under the approved troopship livery, a white hull with a thin blue band, white upperworks and a yellow/buff funnel, with minor variations to this scheme being observed.

After serving a tour of foreign service between 1890 and 1908 the 1st Battalion Bedfordshire Regiment began its journey back to England on HMT Rohilla. A special card was produced to celebrate both the regiment’s homecoming and Christmas: the Bedfordshire Regiment badge was inset on the front of the card with the original regimental ribbon placed down the side, upon which was written ‘Hearty Greetings’. There is an artist’s impression of the Rohilla on the inside, the caption of which indicates the end of a tour of nigh on nineteen years’ foreign service. ‘Our Anchors weighed were homeward bound’ is printed on the opposite page and along the bottom edge the words ‘Old Friends Old Times Old Memories’.

A vintage 1908 British regimental homecoming/Christmas card.

Mrs Selina ‘Kit’ Offord. (Courtesy of Terry Offord)

In 1910 the Rohilla conveyed members of the House of Lords to the Coronation Naval Review of King George V at Spithead, while Rewa conveyed members of the House of Commons. In March 1912 John Daniel Vincer was travelling on the Rohilla with his wife Fanny Elizabeth and their daughter Selina ‘Kit’, bound for England and expecting to arrive in April. Vincer was stationed in India with the Field Artillery in the early 1900s and eligible for leave every five years. Kit was born on 3 December 1902 in Belgaum, in the Indian state of Karnataka and was brought up in Meerut near Delhi. Aged just 10 when her family made the passage to England, Kit gave an account of her experience.

As well as the soldiers and their families, a number of general passengers were permitted to travel on the Rohilla. Kit recalls there being very few civilians. The family were fortunate to have been allocated a cabin with a porthole on one of the lower decks. It was really warm when the journey began. Leaving port the ship headed out across the Indian Ocean making for the Red Sea.

As the Rohilla approached the Suez Canal, Kit was alarmed because as she looked down there didn’t seem to be sufficient water for the ship to pass. She could make out the sand and pebbles and ‘riffraff’ and it didn’t seem sensible to go via the Canal. Once safely through the Suez Canal the ship came into the Mediterranean and then made for Gibraltar. It was the stage from Gibraltar, sailing on towards the Bay of Biscay, that really gave Kit cause for concern and which left her with some very vivid memories.

Kit and her mother were on the top deck in deck chairs, enjoying themselves when everything began to move. The ship was rolling badly and the sea was getting higher; the flooding water caused everything to slide from side to side and only the handrails stopped them from going overboard! It became so rough that her father came up and said ‘Get down into your cabin, because they are sending out an SOS.’ In the end no assistance was needed because the sea seemed to become calm, quite as suddenly as it had become rough. As a result of the weather, the ship had veered off course in the Bay of Biscay, but it was easily corrected as the ship sailed up the French coast towards the English Channel bound for Southampton. Kit was pleased when her mother pointed and said, ‘These are the Needles’ off the Isle of Wight as they entered Southampton Water for she knew her passage was soon going to be at an end.

The ship slowed down as, like all other large craft, it had to wait for a pilot to guide it safely into the docks. In that time a rope ladder had been thrown overboard and Kit soon saw a head appear, sticking up over the rail. A voice called out, ‘Have you heard the News?’ The reply was ‘No’. ‘Well, the Titanic has sunk.’ This didn’t really register at the time, but the Rohilla was docking at Southampton on 15 April, the day that the grand liner Titanic sank! Afterwards everything seemed a little less important. Kit and her family found themselves on a train bound for London.

The overall passage from India to Southampton took some five or six weeks, Kit doesn’t recall anything about the ship itself because she was very young at the time and all ships looked alike. After disembarkation and boarding the train, Selina heard nothing more about the Rohilla for seventy-odd years.

When Kit travelled on the Rohilla, it may have seemed a relatively unremarkable passage, but the narrative of her voyage was given in an interview-type session with her son Terry Offord at my request, in 2007 when she was 104. Selina ‘Kit’ Offord sadly passed away on 11 January 2008 after a two-week spell in hospital. Terry proudly explained that at the age of 105 his mother had lived a very full and eventful life and had never forgotten her voyage on the Rohilla. Terry described how he and his mother had visited the site of the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley near Southampton, which was demolished in 1966 though the chapel is still there, now serving as a museum. They noticed a large picture of a ship on display in the main entrance, by sheer coincidence the Rohilla. Terry put it well when he said that it’s a small world!

In 1913 HMT Rohilla was charged with carrying a number of regiments home to England after a seventeen-year deployment to India and South Africa, including the 1st Battalion Wiltshire Regiment, South Staffordshire Regiment, Gloucestershire Regiment and some Scottish regiments. Colonel Arthur Edmond Stewart Irvine DSO RAMC is known to have travelled on the Rohilla and he once had a wonderful photograph album of his voyage. It featured photographs of the troops, some of the ship’s crew and possibly a ceremony of ‘Crossing the Line’, commemorating a sailor’s first crossing of the Equator and a fine photo of the Drums of the Staffordshire Regiment.

Netley Hospital chapel. (Courtesy of Terry Offord)

Colonel Arthur Edmund Stewart Irvine with some of the Rohilla’s officers.

When war was declared, Captain Neilson and his officers remained at their posts, albeit under the command of the War Office. Though they did not know the specifics of the charter, the crew knew that the ship would be entering a period of uncertainty and possible danger. Under the special circumstances of national emergency the captain, officers and engineers remained faithfully at their posts without demanding any increase in their wages. The company, however, had to promise the deck, engine room and saloon hands an increase in wages as they would otherwise have declined to go on what was regarded as hazardous service.

On 2 August 1914, Herbert Savory, the Rear Admiral, Director of Transports sent a telegram to the company informing them ‘circumstances of grave national import, which will shortly be announced by Royal Proclamation, have rendered it necessary to requisition the SS Rohilla for Government Service as a Naval Hospital Ship.’ The Rohilla returned to her builders, Harland and Wolff, to begin the conversion to accommodate her new role. The work continued day and night for the Admiralty gave the builders just twelve days to have the ship ready to sail.

After spending many years voyaging long distances and enduring long separations from his wife Helen and their three children, Captain Neilson believed that plying between Britain and the northern ports of France, he would at last be able to spend a little more time at home.

Few, if any, of the hospital ships were designed for the task. Most, like the Rohilla, Garth Castle and the China, were converted liners. This type of vessel was ideal for conversion as they had been designed to transport large numbers of people and so had the on-board facilities such as stores, fuel, water, etc., around which to base the medical and nursing requirements. A military ‘standard pattern’ is likely to have been imposed by the Admiralty for outfitting vessels for use as hospital ships. The wards were laid out in an almost identical fashion and indicate an obsession with cleanliness and order. Large open dormitories last used to accommodate troops were converted into wards capable of carrying around 250 casualties. The lower decks provided the most room for wards and though well lit, there appears to have been little by way of natural light and fresh air. The open portholes allowed limited ventilation and only portable screens provided any privacy. The long open wards were the domain of the troops. It was normal practise to have the cots lined up fore and aft with lifejackets suspended at intervals above them.

The cots were designed with what appear to be three legs at either end. These ‘gimballed’ cots were intended to lean with the ship as she rolled from side to side so that the patient was kept as level as possible, reducing patient movement and thus improving the recovery process. Despite the many lifejackets, getting cot-bound patients onto the top deck would not have been easy. Hospital ships were generally fitted with a lift arrangement to enable the movement of non-ambulatory patients between decks, sometimes as simple as an open hatchway through which injured personnel could be lowered on a square wooden pallet. The use of the cranes and derricks on the upper deck would have been limited to transferring patients on and off the ship.

Master of the Rohilla, Captain David Landles Neilson. (Copyright John Littlewood)

At the far end of the ward there appears to be a curve of what is, most likely, the bow section of the ship. (Courtesy of John Mules)

As a rule, there were six or seven wards for the troops divided to either side of the centreline fore and aft with a ‘nursing station’ at the amidships end of the ward and two or three wards for officers, which were adapted by converting portions of the saloons or removing cabin bulkheads, some officers also being nursed in cabins. In contrast to the larger wards for the ‘other ranks’, the wards for higher-ranking officers were far more comfortable. The make-up of the cots would have been similar but with more space between them and curtains to provide privacy to individual berths. It was not unusual to find potted plants strategically placed around the ward. The area that appears to have been the original first-class lounge was most likely used by recuperating and lightly wounded officers.

The Rohilla was equipped with two operating theatres complete with X-ray machines. The theatre looks quite stark and brutal by today’s standards and it is hard to imagine the injuries soldiers sustained being treated in such conditions. The Admiralty were obviously expecting numerous casualties given the number of vessels requisitioned for use as hospital ships. There was not very much room in the theatre to work however. It is likely that in any given emergency, besides the patient, there would have been a surgeon, anaesthetist, with two male sick berth attendants to assist in the procedure and, where necessary, restrain the patient. Female nursing staff, even trained nursing sisters, were still largely kept away from surgery in the services at this period.

The structure for lift assembly can be seen to the left of the photograph whilst the central staircase allows plenty of light to enter the deck opening up the ward. (Courtesy of John Mules)

The officers’ wards were placed on the upper decks with the luxuries of light and fresh air. (Courtesy of John Mules)

The conversion complete and checked by the Admiralty, Rohilla was signed off and Captain Neilson took her into the calm waters of Southampton on 16 August, heading west down the Channel and around the Cornish coast. It was not until the ship had passed the Scilly Isles that Captain Neilson was allowed to open his ‘sealed orders’, which informed him to join Admiral Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands off the extreme northern tip of Scotland.

The battle squadrons had left Portland bound for Scapa Flow on 29 July. Two days later, HMS Collingwood and the rest of the fleet lay in position, guarding the northern entrance to the North Sea, whilst 500 miles to the south on the Baltic and North Sea coasts of Germany, lay the German High Seas Fleet in its heavily defended bases. On the night of 4 August the British ultimatum to Germany expired and the Admiralty flashed the signal to all ships and naval establishments, ‘Commence hostilities against Germany’. HRH Prince Albert was on the bridge of the Collingwood, the midshipman of the middle watch, midnight to 4 a.m., and noted the declaration of war in the diary which he carefully kept each day.

Operating theatres of the period were barren looking places, yet still faced many of the injuries medical staff see today. (Courtesy of John Mules)

The Rohilla’s course crossed the Irish Sea, rounding the west coast of Scotland, and on to Wick, the last stop on the mainland where the ship could be replenished after her long journey north before moving on to the Orkney Islands and her final destination. Scapa Flow is a protected anchorage surrounded by a group of islands 20 miles north of mainland Scotland, providing an ideal natural anchorage and an almost impenetrable haven.

Having completed his training, Prince Albert received his first commission as midship man on the 19,250-ton battleship HMS Collingwood. Liable to bouts of seasickness he had questioned the decision to enlist in the Navy even confiding such to his mother. He was taught the correct use of the ship’s picket boat, not something a midshipman would pick up until he was thorough in all other ship duties. Within months the prince was given the responsibility of running the picket boat, which was approximately 50ft long with sleek lines which seemed to accentuate her cruising speed of around 16 knots. The prince took the name Johnson for security purposes and never revealed his legacy lest people expect special treatment as a confidante of the future monarch.

Unbeknown to the king, the prince had suffered gastric problems which he had apparently concealed, and three weeks after the war had began he collapsed with violent pain in his stomach and appeared to be having difficulty breathing. He was given morphine and poultices applied to his stomach, and though they eased the pain somewhat they did little for his long-term prognosis. He was diagnosed with acute appendicitis and transferred to the hospital ship Rohilla and cared for by Fleet Surgeon Lomas until the arrival of Sir James Reid, the Royal Surgeon, Queen Victoria’s favourite physician, who travelled up from London by train after being called in by the king.

The islands of Scapa Flow. (Copyright John Littlewood)

Prince Albert aged 19 serving as a midshipman on HMS Collingwood.

Dr Ernest Courtney Lomas CB, DSO, FRCS was born on 24 December 1864, and educated at Owens College, Manchester. He graduated MB and ChB of Victoria University in 1888, and took membership of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS) that year. After filling the posts of house surgeon to the Manchester Royal Infirmary, senior house surgeon to the Royal Albert Edward Infirmary, Wigan, and resident medical officer of the Barnes Convalescent Hospital, Cheadle, he entered the navy as a surgeon in 1891. He was promoted to staff surgeon in 1900 for service in the South African War, became fleet surgeon in 1904 and took the fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS) in 1907. He became surgeon captain on 11 September 1918, and was one of the last remaining survivors taken off the Rohilla, before retiring in 1919. During his naval career in the South African War he took part in the relief of Ladysmith, was mentioned in dispatches, and gained the Queen’s medal with two clasps, a special promotion, and the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

At that point, the Rohilla was recalled to the Fleet, but Dr Lomas decided it was not safe to move the prince. So the ship left for Scapa Flow escorted through mined waters by two destroyers. When Sir James Reid joined the ship the prince’s health had improved somewhat and both physicians agreed it was safe for him to be moved. With the assistance of members of the Barnoldswick St John Ambulance Brigade, who had cared for the prince, he was placed in one of the cots used to transfer patients and taken to the quay at Aberdeen. On 9 September his appendix was removed by John Marnoch, Professor of Surgery at Aberdeen University, with Reid in attendance, reporting to the king by telephone.

Dr Ernest Courtney Lomas Fleet Surgeon RN. (Copyright Paul Hutchinson)

The prince’s wish to return to duty on the Collingwood was fraught with complications. A semi-invalid at just 19, he spent considerable time in and out of hospitals and convalescing at Sandringham or in London in the company of his parents and his sister, while his equals fought and died on active service. While the Prince of Wales left for France, and his position on the staff of Field Marshal Sir John French, Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force, the monotony of Prince Albert’s life was broken only by shooting forays at Sandringham. In the interim the prince was attached to the War Staff at the Admiralty, where at least he felt he was doing something for the war effort. Sadly, however, it was uninteresting and not what he hoped it would be: ‘nothing to do as usual’ and ‘It seems such a waste of time to go there every day and do nothing’ became typical entries in his diary.

In February 1915 his wish to get back to the Collingwood was realised, but not for long. ‘I have been very fit on the whole since I returned here but just lately the infernal indigestion has come on again,’ he told Hansel on 15 May (Henry Peter Hansel was the prince’s tutor from 1902). ‘I thought I had got rid of it but it has returned in various forms.’ By 20 June it had become serious, the prince was no longer able to keep any food down and was described as being very mouldy and wasting away. His godfather, Sir William Watson Cheyne, Professor of Clinical Surgery at King’s College London and President of the Royal College of Surgeons, recommended that Prince Albert be sent to a hospital ship for observation. On 12 July, three days after the king visited the fleet (the first time the prince had seen his father for six months) he was transferred from Collingwood to the Drina. On board the Drina, Dr Willan gave a diagnosis of ‘weakening of the muscular wall of the stomach and a consequential catarrhal condition’, for which rest, a careful diet and nightly medications were prescribed. Albert was, in fact, suffering from a stomach ulcer. It is hardly surprising that he did not make a sustained recovery, given that he had been incorrectly diagnosed from the outset.

Despite the prince’s appeals to return to his ship he clearly wasn’t well enough. Two months later, it transpired that the prolonged treatment with enemas and self-isolation studying for his exams on the hospital ship was jeopardising his health. The king was advised that a spell ashore at this point would certainly do no harm. The prince was consequently placed on sick leave and sent to Abergeldie in the company of Dr Willan and Hansel. When he returned to Sandringham from Scotland at the end of October he was still unfit for duty.

Anxiety over the state of his father’s health after a serious accident in France aggravated Prince Albert’s ulcer, making his condition worse. While inspecting a unit of the Royal Flying Corps at Hesdigneul, the king’s horse reared up and fell over backwards on top of him, fracturing his pelvis and leaving him in shock and a great deal of pain. Albert loved his father deeply and they had grown close in the few years since he had left Dartmouth, a closeness enhanced by his long periods of convalescence. ‘May God bless and protect you my dear boy is the earnest prayer of your devoted Papa,’ the king had written shortly after the outbreak of the war, ‘You can be sure that you are constantly in my thoughts.’ ‘I was really very sorry to leave last Friday’, the 19-year-old Prince told his father in February 1915 on rejoining his ship, ‘and I felt quite homesick the first night …’ ‘I miss you still very much especially at breakfast,’ the king replied.

Despite the conditions the rest of the country was experiencing, the Rohilla still hung onto the last vestiges of her original intended role as the final bill of fare produced for diners on the ship was as lavish as one might expect for a cosmopolitan banquet, not something on a ship of mercy:

S.S. ‘Rohilla’ 2 October 1914

Hors d’oeuvre. Canape, à la Russe

Soup. Consommé Cultivateur [a type of cold vegetable soup]

Fish. Flétan bouilli sauce Caradoc [boiled halibut with Caradoc sauce]

Entrées. Céleri au jus [Celery with juice/sauce]

Joints. Roast Haunch of Mutton. Red Current Jelly

Braised Duck with olives

Poultry. Roast and Boiled Potatoes

Cabbage

Sweets. Cabinet Pudding [steamed suet pudding containing fruit]

Fruit Tart and custard. Genoise Pastry [a light, dry French sponge cake]

During her stay in the islands the Rohilla had only one other patient besides Prince Albert, Pte. RMLI Thomas Anderson RN. His service record indicates he discharged from HMS Duncan on 9 October due to a broken leg and went on the books of Chatham Division. The fleet surgeon operated on him to reset the broken bones, and several times more to remove bone splinters. Although the surgeon was satisfied the man would eventually walk again, he thought it would be unwise to move him at that time and the unfortunate rating was kept on board – a move which would sadly proved fatal.

Captain Neilson was provided with all the necessary confidential information relating to the position of minefields between the Firth of Forth and the English Channel. This was new territory for Captain Neilson, who had not navigated the North Sea before, with the alarming possibility of new uncharted minefields and reports of German U-boats. Given the urgency of his voyage and the unfamiliarity of the coastline, Captain Neilson requested the use of a pilot, but his 2nd officer was told that even if one were available it was not standard practise to provide a pilot beyond Scottish waters.

Just after midday on Thursday 29 October, with 234 people on board (the ship’s full-time crew, surgeons, nurses, sick berth attendants, general servants and stewards), the Rohilla left Leith Docks bound for Dunkirk to pick up wounded servicemen. The past three months had served as training, and on the afternoon they left Queensferry everyone had taken part in the boat drill when each man was assigned to his station and inspected by the first officer and the fleet surgeon. With everything in order, they were finally heading off for action.

It had been heavy weather since leaving the Firth of Forth, but the ship was able to cruise at 12.5 knots at the beginning of the voyage. The Rohilla’s course was set to take her off St Abb’s Head on the eastern coast of the Scottish Borders and then down the east coast of England. Under wartime restrictions all navigational aids such as lights and signals were blacked out, posing additional risks to shipping. Such is the coastline that, as the storm burst in from the east, the ship was in a perilous situation. It is sufficiently dangerous on this coast on a fine night with no aids to navigation, but with towering cliffs, a rocky lee shore, a night dark as pitch and no guiding light or warning sound, it could soon turn into one of the severest tests any skipper may be called upon to undertake. The lights on the ship shone in opposite contrast, as brightly as they could, to alert any skulking marauder to its identity as a hospital ship.

On the bridge the last accurate position fix was taken at 4.30 p.m. as the sun set. Thereafter, in the absence of navigational aids, all course corrections and position fixing was calculated using a system of ‘dead reckoning’, mathematical calculations taking account of the effects of time, tidal calculations and wind. By the time they reached the Farne Islands off Northumberland the weather had deteriorated into a full-blown gale, the next set of calculations not due for four hours.

The east coast of England. (Copyright John Littlewood)

At 7.30 p.m. Dr Thomas Caldwell Littler-Jones, a surgeon in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, was on his way to his cabin after the evening tea when he noticed the weather had got worse. At about 10.30 p.m. he felt the ship take on a more pronounced ‘roll’ and went out onto the deck. He observed a marked deterioration in the weather though everything seemed to be proceeding as expected. He returned to his cabin fully aware that he would get no sleep that night.

The following morning Albert James Jefferies was manning his post in the Wireless Signal Station off the Yorkshire coast which also served as the Coastguard lookout on the top of the east cliff.

Observing what he could in such atrocious conditions, he was quick to realise that a vessel steaming from up the coast appeared to be heading for a hazardous reef system known locally as ‘Whitby Rock’, just south of Whitby Harbour. Although the hazard was normally marked with a large permanent buoy, the bell had been silenced and its light extinguished due to wartime restrictions. Jefferies tried in vain to attract the attention of those on board using a Morse lamp, to warn her of the imminent danger. When he thought those on the ship might hear, he activated the foghorn at the top of the cliff, but still there was no reply from the ship.

The captain had command of the bridge with Edward Way the quartermaster at the wheel, and an able seaman on either side of the bridge serving as lookouts, though their view was very limited. The Rohilla’s senior 2nd officer, Archibald Winstanley, had just relieved Chief Officer Frank Albert Bond. Like the other officers on the bridge, Captain Neilson believed the ship was well offshore. The Morse signals were seen by Archibald Winstanley, but they were too quick for him to decipher. He sent for a signaller to decode the incoming message and reported them to the captain.

The coastguard lookout station was rebuilt after being bombed in December 1914, and added to over the years before being totally dismantled and removed in 2010.

After leaving the bridge Frank Albert Bond met the bosun’s mate, who informed him that one of the lifeboats was loose. He reported the problem to the captain, who told him that he would slow the ship in order to make it safe to secure the lifeboat. At that time, 4th Officer Duncan Graham was away from the bridge supervising depth sounding being carried out at the stern of the ship. The sounding revealed a depth of only 144ft, indicating they were a great deal further inshore than they had thought, and he quickly set off to report his findings to the captain. Second Officer Colin Gwynn had just come on watch to relieve Duncan Graham, but instead was sent to the chief engineer with the message to slow the ship down. The captain ordered a slight change in course to take the ship on a route that he thought would keep her out of danger.

At 4.10 a.m. the bosun and Chief Officer Frank Albert Bond were on their way down onto the deck. Captain Neilson had not yet received the Morse signal or the news that the depth sounding placed the ship in much shallower waters. The Rohilla was suddenly rocked by a huge tremor. The captain shouted ‘A Mine my God’ as a huge shock wave travelled the length of the ship, knocking the bosun and chief officer off their feet. Albert Jefferies heard the crashing sound as the ship struck rocks near Saltwick Nab, just south of entrance to Whitby Harbour, and immediately sprang into action. He contacted Charles Sutherland Davy, Chief Officer of the Coastguard Station at Whitby, whose responsibilities covered the use of the rocket apparatus provided by the Board of Trade.