28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

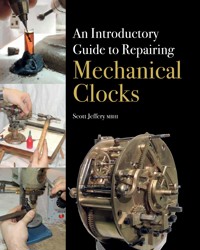

This up-to-date, clearly written and beautifully illustrated book is targeted at the amateur repairer and at the absolute beginner with no experience, as well as at hobbyists who often dabble with, but have little knowledge of, the techniques used in quality horological repair work. Written by a professional clock repairer and using a common sense approach, this workshop companion for the beginner 'keeps things simple' whilst placing an emphasis on the quality of the work. It provides step-by-step illustrated instructions and simplifies a large variety of tasks that are often regarded as being complicated, such as re-pivoting, jewelling and bushing. Moreover, it presents a great deal of useful advice and contains over 400 high quality colour images that help to explain and clarify every procedure that is covered. This no-nonsense guide to rectifying the common faults found in mechanical clocks will be essential reading for all those interested in horology but specifically for the novice who wants to repair mechanical clocks according to best practice. Beautifully illustrated with 424 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 388

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

An Introductory

Guide to Repairing

Mechanical

Clocks

Scott Jeffery MBHI

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2016 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2016

© Scott Jeffery 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 093 5

Acknowledgements

I would like to give special thanks to the following for their support, advice and encouragement throughout the process of writing this book: Chris Baldwin CMBHI; Luke Jeffery MA; Charlotte Shilling; and James Shilling. I would also like to thank the many skilled and educated craftspeople who played a valuable role in my training and education.

Contents

Chapter 1 Introduction

Chapter 2 The Clock Repairer’s ‘Three Toolboxes’

Chapter 3 Workshop Design

Chapter 4 The Timepiece

Chapter 5 Striking Clocks

Chapter 6 Chiming Clocks

Chapter 7 Getting Started

Chapter 8 Materials and Cleaning

Chapter 9 Repairs

Chapter 10 Reassembly

Chapter 11 Tips on Testing

Chapter 12 Setting Up

Chapter 13 Aftercare

Chapter 14 Resources

Glossary

Index

Chapter 1

Introduction

In my first four years as a clock repairer I have served my apprenticeship under the watchful eye of Chris Baldwin CMBHI, achieved MBHI certification, run a profitable clock repair business and been commissioned to write this book. Getting to this stage has been challenging and inspiring, and my intentions with this book are to guide you through what I have come to see as the minimum of knowledge and understanding it takes to become a competent repairer of basic mechanical clocks in the quickest amount of time possible, while still allowing plenty of scope for future developments in the knowledge, experience and equipment it takes to become excellent in the field. I have done all I can to re-imagine my first year, and to write this book in a manner which I would have found easy to understand while being technically interesting.

My biggest challenge was to limit this book to the true beginner, to not delve too deeply into the many subjects of horology and, above all else, to keep it interesting.

Deep theory has always failed to hold my attention for long. The detail given to mathematical examples and long-winded explanations can make reading chapters on theory a real chore. To combat this I have kept the theory portion of this book on a need-to-know basis, but there is a lot to be said. I have opted to leave out any unnecessary mention of historical aspects in order to keep the words flowing and to keep the reader in a technical mindset. Photographs have been provided where I feel you could benefit from their presence, and the accompanying explanations have been written to work with them. In this way you are able to see the components being discussed as though you were sitting with me at the workbench.

My intentions are to make the reader aware of the existence of the many components and theories which they are likely to come across in their first year ‘on the job’ and not to provide a full in-depth study of each. With the understanding that things such as thermal expansion or circular error exist, you are able to make informed decisions. You do not need to be able to calculate it to perform a good-quality repair.

Being relatively new to the industry myself, I completely understand the position of the reader, and what some might see as a disadvantage I use to my advantage.

There are specialist tools for every job, but which ones do you actually need to get it done? Do you really need to invest in a full workshop, ultrasonic cleaning equipment and various lathes just to repair your great-grandmother’s mantel clock? It is unlikely. I have put together a tier system to help you define your needs and buy the necessary level of equipment to suit. These are the ‘three toolboxes’.

If you intend to turn this hobby into a business, full- or part-time, I highly recommend that you contact the British Horological Institute and enrol in their Technician-grade Diploma in clock and watch servicing, and get a qualification under your belt, wherever you are in the world. It can be studied as a distance learning course in your own time, as I did, and it will provide you with certification, industry contacts, a good reputation and all the help and support you could need. For those of you studying the course already, I hope this book will prove helpful in demonstrating the repair processes to you in a real-life scenario and in compiling the theory into a well-organized, readable and uninterrupted whole.

An early 20th century carriage clock, complete with original winding key and travel box.

The front plate of a modern Westminster chiming longcase.

For more information on some of these repair processes, video tutorials, gear train calculators, or just to say hi, I can be reached by visiting www.learnclockrepair.com or www.hampshireclockworks.co.uk.

Enjoy!

Scott Jeffery, BSc, MBHI

Chapter 2

The Clock Repairer’s ‘Three Toolboxes’

I have split the relevant tooling of my own workshop into three separate categories, or ‘toolboxes’. These three toolboxes are intended for:

the beginner who wants only to make small repairs, and perform routine maintenance

the enthusiast who intends to complete the majority of their own repairs and those of friends

the aspiring professional, who intends to undertake repairs for profit.

For every process demonstrated and explained within this guide, I note which toolbox you will need in order to complete it to a high standard. If the job requires tooling which you have not yet acquired, I suggest you buy just the tools needed and slowly build up to the next toolbox. However, if it is a once-in-a-lifetime repair for your interest level, outsource it to a competent, qualified professional who can be found at www.bhi.co.uk.

TOOLBOX 1: THE ABSOLUTE MINIMUM

This toolbox will help you to keep your clock running and extend the period between services, and ultimately keep the costs of those services down. For minimum expenditure, these tools will allow you to regularly oil your clock, repair common breakages and make adjustments to correct the more common issues which may arise. Eventually the time will come when pivots are worn and you will have the choice of either taking your clock to a repairer for overhaul, or upgrading to Toolbox 2 and doing it yourself.

The tools I recommend here are the ones I use most often. I have not suggested makes or names except where offering details of my own equipment because this is not an important part of the choice. What is important to remember is that many of the clocks you will encounter were made two hundred or more years ago, with basic handmade tools which were properly sharpened and well maintained. Provided you use them correctly and with care, the cheapest tool can last a lifetime. Abuse them, and even the named brands will not hold up.

Some tools are luxuries and can simplify or speed up a specific job; these are reserved for Toolbox 3, an advanced collection for the aspiring professional.

There are many tools available which are unnecessary or easily made at home; pivot locators and beat-setting tools, for example. I do not recommend buying these.

The majority of this tooling can be bought at auction for a fraction of the retail price, and can easily be refurbished. This is how I have gathered most of my tooling, and if you are confident in reconditioning your own tools, it is the method I recommend for any beginner.

Screwdrivers

Suitable screwdriver set for clock repair.

For clock work you will need a good selection of screwdrivers. Platform escapements use screwdrivers as small as 0.3mm, while for longcase clocks you can often use screwdrivers more often associated with DIY. In fact, some of my favourite screwdrivers were bought from a DIY supplier, although I had to thin the blades to suit my needs.

I recommend buying a ten-piece set of clockor watchmaker’s screwdrivers from a horological supplier, making sure it includes the larger 3mm blade which is most commonly used in clock work. Choose a set with interchangeable blades as they will chip and require sharpening or replacing, and a swivel top is a nice feature for comfort. For larger work, I use a ‘Stanley Fatmax’ twelve-piece set. This gives a good selection of standard and Phillips screwdrivers. Phillips screwdrivers do make appearances in modern clocks so having a few sizes to hand is useful, although they should not be used in antique work. The blades of the standard ‘flat’ screwdrivers are generally too fat for clock work, but they file down nicely and last a long time.

Refurbishing your screwdriver blades can be done with a sharpening stone or a file. A honing guide can be used to maintain the angle. To sharpen by hand, hold the flat side of the blade down on the stone or, if using a file, support the screwdriver on the edge of the bench and apply the file to the blade. While maintaining the angle, draw it back and forth until a flat surface is produced. Turn the blade over and repeat the process on the other flat until the two sides are even. Finish by holding the blade upright on a sharpening stone and stroking a few times in a circle; this final step removes the weak tip which is liable to chipping.

Pliers

A good selection of pliers is essential in clock work, but for a few basic jobs you can get away with owning just the following:

Combination, end cutting and smooth-jawed pliers.

Combination pliers: the grooved jaws are good for pulling pins, and the cutting part for shortening them. Combination pliers will keep the bill down but are not always the best option.

End cutters: a set of end cutters are my most versatile pliers in the shop. They can be used to cut pins, they can be rocked against the plate (protected by a piece of scrap material) to pull out tight pins and, because the jaws remain parallel as they open and close, they can be used safely to loosen nuts. I have a blunted and polished pair for just this purpose.

Smooth-jawed pliers: a pair of smooth-jawed pliers is necessary for manipulating and shaping soft components; the smooth jaws protect the metal from damage caused by a serrated jaw.

To maintain your pliers, regularly remove any burrs and sharp edges on them with a fine file. If they do not take to filing, as hardened steel will not, use a stone or diamond lap to produce the same result.

Soft Solder, Soldering Iron and Flux

Soft-soldering equipment.

With soft solder you can repair a number of components, fix loose or sloppy components and refinish pallet faces. Although the excessive use of soft solder is frowned upon, it is useful for small repairs. I use soft solder in certain repairs and it is perfectly acceptable when done well.

You will require a supply of lead-free solder and a good flux to help it flow to where you want it. You will also need a high-power soldering iron or an attachment for your micro-torch, as you are generally heating up larger components than standard electrical soldering irons are designed for. Smaller soldering irons are useful for a few repairs but are rarely used. If your budget stretches to it, a small blowtorch is recommended for when a soldering iron is not up to the job; it will also allow you to harden, temper and anneal your materials.

The tip of your soldering iron should be kept clean in order for it to work effectively. To achieve this, wipe the hot end on a damp sponge to clean off flux and excess solder. The tip is best preserved when ‘tinned’ with solder after every use.

Ball-Pein Hammer

Ball-pein hammer for general work and riveting.

A ball-pein hammer of about 110 grams (4oz) to 170 grams (6 oz) is just right, although hammers are generally measured and sold in oz and the size is down to personal preference. I personally use a small 4oz hammer with a short handle of about 15cm (6 in). This gives me a good ‘whack’ when needed but gentle controlled taps most of the time. The ball-pein hammer is good for riveting and stretching metals, as well as for providing blows to accurately placed stakes and punches. Any dents and marks on the hammer head will be transferred to the work piece when you hit it, so periodically polish the working surface for best results.

Needle Files

Selection of needle files.

A good selection of needle files is not absolutely necessary at this stage, but it is recommended. If you are soldering, then they are useful for cleaning the materials back to bare metal beforehand, and for removing excess solder afterwards. I use an old square needle file clamped in a vice for rotating the collets in modern minute hands, for making sure that they strike dead on the hour. They can be used for removing burrs and wear grooves in some components, and can be used for reconditioning your other tools as they wear and chip.

To maintain your needle files, periodically remove any material stuck between the teeth by running the tip of a razor blade through the grooves. Applying chalk to the teeth before use helps prevent this build-up, whilst filing soft metals like solder increases the ‘clogging’ of the file teeth.

Clock Oil and Oiler

Clock oil and oilers.

You should be using a good-quality clock oil for maintaining your clocks, such as those sold by horological suppliers. When oiling platform escapements you should use a medium watch oil. For a clock oiler you can use a piece of brass wire, with the end hammered flat and filed into a diamond shape. For oiling watches I would suggest buying a commercial oiler. I prefer a pen-type oiler which dispenses oil with the click of a button.

The oil pot and bottles should be kept out of direct sunlight and dusty areas to prevent deterioration of the oil, and the working supply should be kept clean and periodically refreshed.

Movement Holders and Test Stands

Movement holders for use during repair.

You are going to need to test your clocks thoroughly after repairing them, and various test stands will be needed for the many types of movement you will be working on. Plans for building various useful test stands can be found in the resources chapter; alternatively you can buy commercial test stands if you decide not to make them yourself.

You should also buy a set of ‘clock legs’ or ‘movement clamps’ as shown in some of the pictures, for when you are working on the movement, but you can make do with a short section of 10cm (4in) PVC tube, or the cardboard from the centre of a roll of wide masking tape. For working on platform escapements you should buy a set of round watch movement holders or plastic/boxwood rings.

Let-Down Tool

Let-down tool with interchangeable ends.

Safety first. You can let the power out of the mainsprings in many ways: using the key is dangerous because you have to keep adjusting your grip while holding the click open. Letting the movement run down is acceptable, provided it is not in bad condition and is a timepiece, but I would not like to try letting a worn, fully wound chime train down without the correct tooling. Of course, if you only intend on working on weight-driven clocks, you can pass on this tool entirely.

A Selection of Loupes

For smaller clocks, carriage clocks and platform escapements loupes are necessary. Get a good selection of loupes; 2×, 5× and 10× would give you a nice variety. The material of the body does not affect how well the loupe works, just how it feels. For those who wear glasses, you can buy clip-on loupes with fold-down lenses which give a wide range of magnification.

Selection of jeweller’s loupes.

Demonstrating the magnification obtained by using a jeweller’s loupe.

Some people struggle to hold the loupe in the folds of skin around the eye, a skill which when mastered is comfortable and convenient. But if you find it a problem, purchase a loupe with a wire headband to hold it in place for you.

Tweezers

Tweezers and a diamond lap for their maintenance.

Tweezers come in a huge variety and it can be confusing deciding which to buy. I would suggest a minimum of two pairs. One pair should have ‘fine’ or ‘superfine’ tips for use when working on platform escapements, handling tiny screws or tweaking hairsprings, and then a pair of ‘medium’ tips for heavier work – locating pivots, fitting pins, etc. I personally have a pair of ‘best’ tweezers for fine work, and a pair of ‘rough’ tweezers for abusing, and then my everyday-use tweezers. Buy anti-magnetic stainless steel tweezers; there is no need for anything fancier than this.

Bent tweezer tips can be straightened by using your smooth-jawed pliers. Grasp the tip and pull, allowing the pliers to slip across the surface of the tweezers. With practice you can maintain a perfectly straight tip. Finally, use a fine diamond lap or stone to grind the ‘working surfaces’ flat and remove any burrs. The perfect tip is one which does not spread as closing pressure is applied.

Rags

A selection of rags is useful for many things: wiping oil off plates, handling brass, releasing broken springs from the barrel under control and wiping coffee off your chin. Keep them graded according to cleanliness.

TOOLBOX 2: THE COMPETENT AMATEUR

Our second toolbox will allow you to overhaul or ‘service’ most types of clock: stripping, bushing, polishing the pivots, cleaning, oiling and reassembling the movement. These tools are in addition to Toolbox 1 and are those which I regularly use when overhauling movements, from basic timepiece carriage clocks all the way up to musical Victorian longcase clocks. This toolbox does not include specialist tools like the truing callipers or the watchmaker’s lathe; these will be part of Toolbox 3.

You will still be limited on component manufacture at this point, and some of the more complicated repairs will be beyond the capabilities of your equipment and experience. However, 80 per cent of jobs which pass through our workshop could be completed using these tools alone; where we choose to use more advanced tooling is usually for speed and cost-effectiveness.

Mainspring Winder

Mainspring winder.

When you start disassembling clock movements it is absolutely necessary to remove and inspect the mainsprings. This is best done with a mainspring winder. Using the mainspring winder helps to avoid distortion of the mainspring, and is by far the safest way of removing and fitting strong springs such as those used in fusee clocks. There are multiple designs of mainspring winder and you should pick the one you find most comfortable to use. My choice of mainspring winder is, in my opinion, the simplest type and the one I highly recommend. Instructions for its use and photographs can be found in the later chapter for reassembling the movement.

Pivot File and Burnisher

Pivot file and burnisher.

This is used for correcting and work-hardening worn pivots. As oil dries and gathers dust, the pivots begin to wear and become pitted and grooved. If this is not corrected when the movement is cleaned, there will be excessive friction in the pivots and accelerated wear to the pivot hole. The pivot file and burnisher is often a double-ended tool. The file end is an extremely fine file and cannot be substituted for a needle file, while the burnisher is a flat, hardened piece of steel, lightly grained across its width. The burnisher has a sharp edge and a rounded edge to suit different pivot types. Be sure to use the correct edge in contact with the shoulder in order to ensure no material is left in the corner which would cause the arbor to bind in its pivot hole.

Maintaining the burnisher is done by refreshing the cross-grain periodically on a medium stone or emery paper stretched over a piece of wood.

Pin Chucks/Hand Vices

Selection of hand chucks and vices.

A selection of pin chucks and hand vices is necessary for holding small components and tools; they are also used when correcting worn pivots if a lathe is not available. Buy a graduated set which will serve most purposes.

Cutting Broaches

Large cutting broach.

Cutting broaches are used for opening pivot holes to an exact size, either to fit a bush or to accept a freshly burnished pivot. The broach itself is a long tapered piece of hardened steel, ground with five sides. The points at which the sides meet form a cutting edge. The broach is inserted into the hole and twisted. It is best to attach a handle to your broaches, or use a pin chuck. Maintenance of the cutting edge is by stroking the five flats on a stone or diamond lap, ensuring that their angle is not changed. Good-quality broaches have a reliable taper and will last a lifetime if treated well.

Smoothing Broaches

Large smoothing broach.

Smoothing broaches are used after the cutting broach and are hard steel tapered rods which are ground perfectly round. As a smoothing broach is twisted in a pivot hole with a small drop of oil, it burnishes or work-hardens the surface of the brass.

A broach can also be used for checking a pivot hole for wear by inserting it into the hole, which should be as round as the broach is. A worn pivot hole will show a slither of light to one side of the broach.

Brass Bushes or Bushing Wire

Good selection of brass bushes for clock repair.

Brass bushes are consumable items which are used to correct badly worn pivot holes. A wide selection should be purchased and graduated sets are available. The outer edge of the bush is slightly tapered to match that of the cutting broach. The inner hole is perfectly concentric to the outer edge and should be opened and burnished with your broaches. Brass bushes can be made in the lathe although much work is saved if a good-quality set is purchased.

Oil Sink Cutting Tools

Oil sinks are needed to retain the small drop of oil placed on the pivot holes. When you bush a worn hole the original oil sink will be cut away and you need to put it back. Oil sink cutters are readily available from suppliers and look like miniature pizza cutters. The round cutting blade is placed on top of the pivot hole where it will centre itself, and rotated in the fingertips. A round dimple will soon appear which will eventually become the oil sink. I use a modified drill bit in which the end has been shaped and polished to produce a good-quality oil sink.

Stakes and Anvils

Selection of stakes and anvils.

Riveting punches and a staking block or anvil are needed for riveting large bushes. In fact, they serve so many purposes that it is highly recommended to just buy a good-quality staking set as listed in Toolbox 3. For this toolbox, simple domed and flat punches and a block or small anvil will suffice.

Machine Vice and Bench Vice

Machine vice and soft-jawed bench vice.

A machine vice makes a very handy bench companion and can be used for a huge variety of applications, from holding components for filing or being used as an anvil, to acting as a temporary movement holder. A small bench vice is also handy; I use mine for holding a block of hard wood for refinishing pivots, closing tight spring barrels and holding mainsprings when remaking the hooking eye, etc.

Bristle Brush and Chalk

Stiff-bristled brush and chalk for cleaning components.

Chalk-brushing is the traditional method of adding a final finish to clean clock components; the stiff bristled brush is drawn over the chalk and then used to scrub the plates thoroughly. Often the plates will take a polish from this action and all traces of cleaning residue will be removed. The chalk will absorb any remaining cleaning product as well as act as a light abrasive to polish the brass work.

Scratch Brush

Fibreglass scratch brush.

A fibreglass scratch brush is a small pen-like tool which has a fibreglass tip. The fibreglass provides a sharp scrubbing action which moulds itself to the situation in hand. Scratch brushes are indispensable when it comes to cleaning pinion leaves and other tough-to-reach areas. As the tiny glass fibres break away they are liable to become stuck in your fingers, so I recommend using latex gloves or finger cots and to sweep the bench afterwards. The fibreglass tips do wear but refills are available.

Pegwood

Small selection of pegwood.

Pegwood can be purchased from horological suppliers in various diameters. These slim wooden rods have a tight grain which adapts well to being sharpened to a fine point. This point is inserted into a pivot hole and twisted, re-sharpened, and the process repeated until it emerges from the hole spotlessly clean. ‘Pegging out’ pivot holes is an important part of the cleaning process, and pivots which are not pegged out are certain to wear sooner than those which are. At a pinch, a cocktail stick will work well.

Bench Knife

Two types of blade for use at the workbench.

A good knife will be needed for sharpening your pegwood, but you will find many other uses for it. A sharp pocket knife will do.

Diamond Files

Diamond needle files, excellent for filing hardened steel.

Diamond files are synthetic diamond-impregnated files which work excellently in situations where a steel needle file will fail to cut. I use diamond files for remaking and repairing the hooking eyes of mainsprings, a job which will destroy steel files in no time.

Tin Snips

Tin snips, for cutting sheet metal.

These are used for trimming away the torn end of a mainspring in preparation for making a new hooking eye, although you can just as easily snap the excess spring away as the steel is hardened and brittle, or just replace the mainspring entirely. These are not a necessary purchase, but are handy.

Blowtorch

A micro blowtorch, for everything from soldering to heat treating.

A blowtorch will be used for many jobs: annealing materials before straightening bent pieces, hardening and tempering, soldering, bluing, etc.

TOOLBOX 3: THE ASPIRING PROFESSIONAL

The aspiring professional’s toolbox is essentially a cut-down list of the tooling in my workshop. In addition to Toolboxes 1 and 2, Toolbox 3 will include lathes, depthing tools and cleaning machinery, etc. You will need a large workshop to house this level of equipment. However, with these tools, a little experience, and the knowledge shared within this book, you will be ready to go professional and produce good-quality work economically.

Watchmaker’s Lathe

An 8mm watchmaker’s lathe.

Your lathe will quickly become the most valued tool in the workshop. With it you will be able to re-pivot arbors, turn balance staffs, file and burnish pivots quickly, bush barrels, and make screws and true eccentric wheels, etc. There are so many lathes out there that it can be very difficult deciding what you need.

Any complete 8mm watchmaker’s lathe will satisfy most of your needs: they are excellent for turning by hand and can be picked up second-hand for a reasonable price. Accessories are widely available at auctions and online, while some manufacturers still make new collets and tailstock accessories. I have found some limitations due to the small size of this lathe so I have a second one in the workshop.

The 10mm Pultra serves all the likely needs of the clockmaker. When well equipped you are able to do all the work of the 8mm lathe, but you have the ability to work to a larger scale. I use my 8mm BTM lathe for hand-turning and making small components as well as for re-pivoting arbors because I like its small and unimposing stature for up-close work. For all other jobs I prefer the 10mm Pultra lathe, which works nicely with the sturdy cross slide and drilling tailstock for boring holes and truing wheels.

With the right accessories any lathe can be made to suit your needs, but for the aspiring clockmaker I recommend starting with an 8mm lathe, and when this begins to show its limitations upgrade to a 10mm lathe as I did. Buy the most complete lathe possible; a full set of collets and step chucks is highly advisable, and three- and four-jawed chucks are a huge advantage for some work. A drilling tailstock is advantageous but you can do good work without it provided you have a tailstock centre to guide you when drilling by hand.

Depthing Tool

Clockmaker’s depthing tool (large).

Every time a worn pivot hole is bushed, it is important to ensure that the pivot is put back to its original centre point. Unfortunately this is often overlooked and, with time, the pivot hole wanders away from its original centre. Eventually the depthing between a gear and pinion pair becomes so bad that the clock will stop for seemingly no reason. When this happens you need to check the depthing of all the wheels and pinions to see where the problem lies and to do this you need a depthing tool.

Depthing tools allow you to set up the wheel and pinion so that you can adjust their depths with micrometer accuracy. By experimentation and a good understanding of the theory you can find the correct position for the pivots and mark the clock plates with the scribe for drilling.

Truing Callipers

Pair of truing callipers.

A pair of truing callipers can be used for both truing and poising any small wheel, such as the balance and escape wheels encountered when working on platform escapements. This will not be your most frequently used tool but they cost very little and can be extremely useful in diagnosing problems with platform escapements.

Jewelling Tool

Jewelling press.

The jewelling press has many uses besides removing and fitting press-fit jewel-holes. It is similar in design to a staking set, but at the top it has a micrometer depth stop and a lever to gently press the tool into action. The jewelling tool comes with a number of reamers used to open a hole and produce a perfect fit for its jewel. The reamer is then replaced with a pressing tool to press the jewel into the hole with no danger of damage and to ensure absolute parallelism. The depth to which the jewel is pressed into the plate is controlled by the micrometer gauge, thus giving excellent control of end-shake to the wheel.

The jewelling tool often comes with accessories for tightening cannon pinions, reducing holes in small hands and for use as a micrometer, and I often use mine for accurately bushing small pivot holes in platform escapements.

Rubbed Jewel Tool Set

Set of jewelling rubbers.

Comparison of closing and opening jewelling rubbers.

Rubbed-in platform jewels can be replaced by manipulating the setting using these tools. They are cheap enough second-hand if you can find a set, which makes it possible to repair antique jewel-holes. There are three sizes of the opening and three sizes of the closing tool. Their use is covered in the repairs chapter.

Staking Set

Complete staking set.

A good staking set has a huge variety of uses and should be something you aim to buy relatively early on in your career. The staking set is an improvement over the riveting stakes and anvil from Toolbox 1 because it provides a method of holding a punch vertically and acts as a third hand, so you can use one hand for holding the component and the other for holding the hammer. It also provides either a hole or specially designed stake on which to position the component to be riveted, pressed, stretched, closed, driven or punched.

Staking sets are used when fitting a balance staff, driving out broken screws, reducing or reshaping holes, riveting small wheels to pinions, removing and replacing rollers and balance springs, and so much more.

To use the staking set, first take the conical tool and place it in the frame; this will centre the hole in the staking block with the punch guide-hole. Lock the staking block with the screw or lever on the rear of the tool and replace the punch and stake with the correct tool for the job. The punches can be either pressed by hand, or tapped with a small hammer.

Ultrasonic Cleaning Tank

Ultrasonic and watch-cleaning machines.

Although not strictly a necessity, an ultrasonic cleaning tank will greatly increase your efficiency and turnaround time, as well as drastically reduce the effort needed to clean intricate components properly. I have added this to Toolbox 3 because it can be a rather expensive investment intended for the aspiring professional. When cleaning with an ultrasonic tank, a process which I describe in full later on, you submerge the components fully in cleaning fluid and the ultrasonic tank creates thousands of tiny implosions which blast the soft grime away from the solid metalwork of the movement which is simultaneously degreased by the cleaning agents in the fluid.

Watch-Cleaning Machine

Rotating watch-cleaning machines are excellent for cleaning small components such as platform escapements because the cage system and gentle agitation of the cleaning fluid ensures that no damage comes to the parts while they are cleaned. Often they include a drying chamber into which the cage is placed for several minutes after the fluid has been rinsed off.

Micrometer and Callipers

Measuring equipment for everyday use.

Accurate measuring is essential when working with such tiny components, especially when measuring to order new springs. Clock mainsprings are often as thin as 0.25mm and are graduated in stages of 0.05mm so trying to use a ruler or ‘eyeballing it’ does not work. Vernier callipers and micrometers are best bought in millimetres rather than inches in the UK as this is how new components are labelled and supplied.

Pillar Drill

Small pillar drill.

A small pillar drill is essential when you start manufacturing components. There are many manufacturers of micro-drills, but provided that there is some form of speed control and some ‘feel’ to the feed arm, any model will do. Accuracy is extremely important so it is best to measure the eccentricity of the chuck provided by fitting a steel rod which is known to be perfectly round and straight (a ground carbide drill shaft is good for this), and setting up a dial gauge to rest on this rod as near to the jaws of the chuck as is possible. Zero the dial and rotate the drill chuck by hand. The dial gauge should show no significant deviation as the rod rotates. If your chuck is showing eccentricities, rotate it until the lowest reading is obtained; at this point the rod is furthest from the gauge. Mark the chuck with a marker pen in line with this point and remove it from the drill following the manufacturer’s instructions. The mark you made is the highest point on the three jaws of the chuck, which is pushing the rod out of centre. Use a small diamond file and reduce the jaw (or jaws if the line falls between two) nearest the mark and retest. Continue to repeat this process until concentricity is achieved.

Files and Stones

Good selection of files and stones.

You already have a selection of needle files and diamond files from Toolboxes 1 and 2, but when making components (as will be possible with Toolbox 3) you will need some larger files suited to more general engineering work. Buy a selection of new files in the 10cm (4in) and 15cm (6in) sizes; second cut is good for clock work. Half-round files are very useful in the smaller 10cm size for crossing out large wheels, and large flat files are useful for flattening the surfaces of components. You will need a variety so I recommend buying a set. Fit handles to all files over 10cm (4in) as the provided tang is not usually long enough to use as a handle (as with needle files).

Various stones can be very useful; my favourite ones are diamond laps of medium and fine grade. Modern synthetic stones are generally better than the old-style oil and Arkansas stones which chip easily and pit with use. Diamond stones or ‘laps’ come in a variety of grades and make excellent general-purpose grinding and sharpening stones; they are used dry and cleaned very occasionally with water. As the ‘diamond’ coating is bonded to a metallic base, they do not become pitted with wear or chip when dropped and they last for a very long time, becoming slightly finer as the coating wears down. If you find that shaped stones would be a useful addition to your toolbox, I would recommend Degussit stones which are extremely hard and hold their shape; the finer grades provide a good finish, whilst the coarser grades can be used almost like a file.

Piercing Saw

Piercing saw with a selection of blades.

When making components you will need to use a piercing saw to rough out intricate shapes, and follow that up by filing to size and stoning to a good finish. Piercing saw frames come in a variety of depths, but for the clockmaker piercing mainly small components, a 7.5cm (3in) frame should be adequate. The blades are inserted into the frame so that they cut on the pull stroke rather than the push stroke. This stops the frame from flexing which would result in the blade going slack and breaking.

The saw blades themselves come in a variety of grades, ranging from 8/0, 7/0 and 6/0 to 1/0, 0, 1, and so on up to 8, with 8/0 being the finest, with the highest number of teeth per inch, and 8 having the largest teeth. Selection of the correct saw blade for the job is not hugely scientific; for thin materials, use a finer blade, aiming as close as possible for a minimum of three or four teeth ‘within’ the thickness of the material at any time. A smear of beeswax on the blade or a drop of clock oil helps the blade cut freely.

Hacksaw

Large hacksaw.

A hacksaw and junior hacksaw are useful for quickly removing the bulk of material to be pierced or for cutting a rough blank for making a component. Hacksaw blades are fitted to cut on the push stroke and are measured in teeth per inch (tpi): 32tpi is good for most situations in clock work.

Taps and Dies

Examples of taps and dies with their holders.

A good selection of taps and dies can be expensive but is worth every penny. BA sizes are useful in clock work so I would recommend starting with a set of BA taps and dies, and add to it over time with the metric taps and dies which are now used by major manufacturers. I find my most commonly used taps and dies to be 5BA and 9BA. They come in carbon steel (CS) or high-speed steel (HSS).

To maintain the condition of your taps and dies, advance the cutter forwards one turn, then half a turn back to clear the swarf and break the chips of material as it cuts. You should use a good cutting oil which will both preserve the cutting edge and prevent rust during storage.

Silver Solder

This is the missing link between soft solder (electrician’s solder) and brazing. The required heat source will be more powerful than that used for soft soldering, and the flux will also be different. Silver solder is used in situations where structural integrity is necessary and does require some practice to get good results. It comes in grades rated by the temperature at which it melts. This allows you to solder two or more components in close proximity without melting the previous joint. For example, start with a high temperature solder for joint 1, and then use a low temperature solder for joint 2. Joint 1 will then stay solid while the soldering of joint 2 takes place.

Smiths Little Torch

Oxy-propane micro-torch for an intense heat source.

This is an excellent oxygen/propane micro blowtorch which produces brilliant results when silver soldering due to its intense high-quality flame. My abilities in soldering grew instantly upon purchasing this bit of kit.

Chapter 3

Workshop Design

Your workshop requirements will depend on how involved you intend to become. For those of you who want to maintain your own clocks between overhauls and keep your bills down, you need nothing more than a clean desk, a kitchen sink and somewhere to keep your tools. At the other end of the spectrum is the aspiring professional for whom I recommend a custom-designed workshop, set up for maximum efficiency of the space. A spare bedroom or large garden shed will work, but you could consider a rented workshop to provide a professional front for dealing with customers.

When designing your workshop you should consider any inconveniences caused to those around you, especially regarding parking and deliveries at the inconvenience of your neighbours. If you cannot provide adequate parking, you should consider collecting and delivering where possible. If you are working with the public you will require a higher level of insurance to cover any potential injury or damage caused on site whether at your premises or theirs, this is called public liability insurance and will cover you for most conceivable interactions with the public. Your contents insurance provider should be able to provide public liability insurance, a package deal is the cheaper option. Your car insurance should also be upgraded to cover the transportation of customers property.

As your skill and understanding increases, so will your tooling and the workspace required to store and use it. You will soon have a lathe (or two), a pillar drill, a large bench vice and several clocks on test at any time. For maximum efficiency you will need the most commonly used tools to hand, including your lathe and a micro-drill of some form. Your workbench should be a comfortable height for you to work at when seated. You will benefit from making a small bench-top table to raise the worktop up to a height just below your collar-bone: this makes putting the plates of a movement back together much easier by raising them to eye level. I also recommend making a raised table for your lathe, so that you can look down on the work piece at roughly a 45-degree angle without having to hunch. Eventually you will be turning balance staffs and re-pivoting at this lathe, during which you will spending up to a couple of hours at a time in the same position. Plans for these tables can be found in the resources chapter at the end of this book.

My workbench.

You will need a large workbench. When you are working on a longcase clock you will need space to set aside the 30cm (12in) dial and seat board, a place to store the components as you strip them, space for your tools and at least a 30 × 30cm (12in) square of clear, uncluttered space for performing repairs. Bear this in mind when buying or building your workbench. I recommend that your workbench has a sacrificial surface which can easily be replaced. My bench has a 120 × 60cm (4 × 2ft) top for the main working area: this is a standard size for sheet hardboard and plywood so I can simply lift it off and fit a new piece periodically.

Natural light is by far the best if available; otherwise, well-placed electric light will do a reasonable job. Daylight bulbs produce a simulated natural light which is kinder to the eyes and easier to work under. Place a well-diffused light high up above the workbench to avoid strong shadows and have a small bench lamp for when stronger light is needed.

General safety should also be considered in the design of your workshop. The majority of your electric tooling will most likely be bought from auction, and date from decades ago, it is wise to re-wire where possible, adding earth wires to the metal frames of the machines. Electrical equipment should be located away from water sources. It would be wise, if you are building your workshop from scratch, to add an isolation switch to cut off the power supply to the entire workshop at the end of the working day, leaving a single double socket power source for testing electric clocks over night. This ensures that all of that outdated equipment is fully shut down whenever you are not on site.

Hazardous materials come into play on a daily basis when working with clocks, from the propane source for your blowtorch down to the ammonia in the cleaning fluids. Adequate ventilation is a must, if possible I do recommend locating cleaning equipment and gas supplies outside of the building in a shed or converted outhouse, but if this is not possible, an electric ventilation fan, ducted to the outside of the building is wise, although a large open window will suffice if security is not impaired.

Of course it is also wise to take full advantage of personal protective equipment to avoid personal injury. Safety glasses when working the lathe or grinder, Leather gloves when using the polishing mop or mainspring winder, industrial rubber gloves when working with cleaning fluids etc. and of course regular cleaning routines, and fire extinguishers close to hand.

Disposal of hazardous waste should be taken care of by a certified professional. It is a good idea to keep old cleaning fluids well sealed in a garden storage container until several gallons have been collected, when a collection can be made at a lower cost than several intermediate collections.