35,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

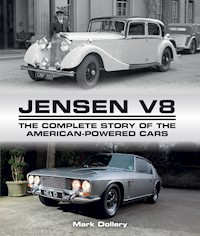

The story of Jensen favouring American V8 power began during the 1930s, with the building of their first prototype car. Although this pre-war period was short-lived, this would be the start of what was to eventually become one of the company's main trademarks - the V8 engine. This new book examines the C-V8, Interceptor and FF models as well as Jensen's use of Chrysler, Ford and General Motors engines. The history, design, development and production of these cars is covered and the book is illustrated with 300 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

JENSEN V8

THE COMPLETE STORY OF THEAMERICAN-POWERED CARS

Mark Dollery

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2016 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2016

© Mark Dollery 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 123 9

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace and credit illustration copyright holders. If you own the copyright to an image appearing in this book and have not been credited, please contact the publisher, who will be pleased to add a credit in any future edition.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 TWO INNOVATORS, ONE DREAM

CHAPTER 2 THE PRE-WAR V8, STRAIGHT-EIGHT AND V12-CYLINDER MODELS 1934–1941

CHAPTER 3 THE POST-WAR STRAIGHT-EIGHT AND SIX-CYLINDER MODELS, INCLUDING V8 PROTOTYPES 1946–1963

CHAPTER 4 SUB-CONTRACTING WORK 1948–1967

CHAPTER 5 JENSEN C-V8 MK. 1, 2 AND 3 MODELS 1962–1966

CHAPTER 6 THE P-66, 1964–1966 – FILLING THE GAP

CHAPTER 7 JENSEN INTERCEPTOR MK. 1, 2 AND 3 MODELS 1966–1976

CHAPTER 8 JENSEN FF MK. 1, 2 AND 3 MODELS 1966–1971

CHAPTER 9 JENSEN INTERCEPTOR S4 MODELS 1983–1992

CHAPTER 10 JENSENS IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would very much like to thank the following organizations, people and sources for their generous assistance in helping me complete this book. I sincerely hope I have done justice to this much-loved British marque – it greatly deserves it.

The Jensen Owners’ Club, in particular Keith Andrews, Dave Barnett, Tim Clark, Nick Cooper, Steve Hodder, John Lane, Paul Lewis, Tony Marshall, Zachary Marshall, Francis Pullen, John Staddon, Dave Turnage, Chris Walton and especially Mike Williams, for his help regarding the pre-war and P-66 models, as well as Derek Chapman for information regarding the P-66 restoration.

Many thanks also go to a band of Jensen aficionados. Keith Anderson supplied me with information regarding the development of the S-V8 models. He was the first writer to cover the Jensen marque in real depth, submitting many informative and interesting articles for the club over the years, and has become an accomplished author in his own right on the subject. Richard Calver allowed me to use some of the information from his Jensen site. Richard is someone to whom every enthusiastic Jensen owner owes so much, because of all the painstaking and in-depth research he has carried out over the years regarding the history of the marque.

Brandt Rosenbusch, head of the Historical Services at the Chrysler Group LLC in the United States, helped me with the technical information regarding the Chrysler engines and transmissions.

Thanks are also due to the following: The Ford Motor Company, General Motors, Good Relations Ltd, Richard Appleyard Motors, Cropredy Bridge Garage, Rejen Sales Ltd, Martin Robey Ltd, Hastings Motor Sheet Metal Works and Jensen International Automotive; The Aston Martin Heritage Trust, British Motor Industry Heritage Trust, David Zatz (Allpar), Graham Vickery (Sunbeam Tiger Owners’ Club), Stephen Lewis (Post Vintage Humber Car Club), Buck Tripple (California Association of Sunbeam Tiger Owners) and The Slade Fan Club; Autocar and Motor, Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick library, the Isle of Wight records office and the DVLA.

I would also like to thank Andy Chapman and Eric Christoffersen for the technical information they supplied, as well as my mate and proud FF owner Arthur Ingleby for his constant help and support during the writing of this book.

Finally, last but not least, I thank my dear wife Andrée for her patience and understanding while I was completing this book.

I dedicate this book to my son Benjamin.

INTRODUCTION

My first memory of a Jensen motor car dates from around the mid- to late 1960s, when, as a young boy, I watched a certain spy series on television called ‘The Baron’. It only ran for one season, but most of the episodes featured a grey C-V8, including a great high-speed run and skid sequence in the opening credits. In the early 1970s, Jensen became the car of choice for the TV crime-fighter once again, as the personal transport for ex-’Man from U.N.C.L.E.’ star Robert Vaughn in ‘The Protectors’. This time it was the Interceptor that took centre stage.

I had been well and truly bitten by the Jensen bug, but it was not until the summer of 1974 that I actually experienced a Jensen in the metal, so to speak. Growing up in a rural village on the Isle of Wight, it may seem unlikely that expensive, hand-made GTs like Aston Martin and Jensen would feature much in my youth, but they did! As a thirteen-year-old, carcrazed schoolboy, I worked part-time at my local garage, mending punctures, serving petrol, checking customers’ battery, oil and water levels and tyre pressures, cleaning cars and, when I got the chance, driving old bangers – Morris Minors, Minis, 1100s and Ford Anglias – around the forecourt. However, Jaguar was my all-time favourite marque, and I was very fortunate in that the business also specialized as a second-hand Jaguar dealer and breaker, employing some very experienced and competent mechanics as well as a bodywork specialist. They looked after not only the six-cylinder Jags, but also the mighty 5.3-litre V12-powered models, and customers soon began to trust them with the servicing and repairs for specialist cars such as the Aston Martin DB5/6 and the even more complex DBS V8 model. I remember in the summer of 1976 the proprietor of the garage, Mr John Foss, had a 1970 vintage DBS/6 automatic up for sale, at the princely sum of just £3,750. How times have changed, even though that was a fair amount of money in those days for what has always been considered to be the least desirable of Aston Martins.

One evening, I spotted a gold Mk.2 Interceptor in the body shop having its front wing repaired. To me it even looked better than on the television. The Jensen in question was chassis number 123/4225, registered GPG 699K, a 1971 Mk.2 in Metallic Fawn with all the factory options. Little did I know then that, thirty-three years later, I would become the proud custodian of that very same car, affectionately referred to as ‘Benson’ by the previous owner! I can also remember my very first spin in a Jensen, a customer’s Brazilia Blue 1973 Mk.3 Interceptor, which was at the garage for a service. I have fond memories of John Foss blasting the Jensen along the island’s country roads. I was pinned firmly to the passenger seat by the acceleration and revelled in the marvellous burble that only those wonderful V8 engines could produce.

Over the years of my Interceptor ownership, I must confess I have become somewhat obsessed with the old girl. After almost a lifetime of constant admiration for this Grand Touring icon, finally getting my hands on one means that life has never been quite the same. I have been a true petrolhead for as long as I can remember and motor cars have always played a major part in my life. Although Jaguar has always been number one on my list of motoring marques – I have owned nearly twenty over the last thirty-two years – just recently, the ‘Coventry Cat’ has had some fierce competition from the ‘West Brom Ferrari’.

Being a nuts and bolts man, dismantling and reassembling my first Jensen has been a learning curve that I have enjoyed immensely. The Jensen Owners’ Club has offered excellent support and I strongly recommend them to anybody considering the purchase of any Jensen model. A number of specialists up and down the country also offer superb advice and help, whether you are purchasing parts or doing your own servicing and repairs. Jensen is one of those desirable classic marques that are affordable, with a spare parts source that is plentiful and inexpensive, yet its pedigree back in its heyday, certainly regarding the C-V8 and Interceptor, made it a credible alternative to Aston Martin. The Jensens may have been hybrids built in the West Midlands, but they could cut it with the best.

This book mainly covers what I think were Jensen’s most exciting models, the pre- and post-war V8-powered machines. Stylish, very powerful and fast, these could be considered to be Jensen’s first competitive ‘supercars’ – certainly, in the case of the post-war models. They represented the pinnacle of the company during the 1960s and 1970s.

Whether you are interested in the development and engineering side of each model, the key players of the company or the history of this famous British marque, I hope you will find in this book the information that you are after. When I began writing it, in 2012, we were on the brink of witnessing a new era for the brand, with an all-new aluminium-bodied Jensen Interceptor due to go into production for 2014. Hand-made and manufactured in the Midlands, this exciting new venture could have brought Jensen back where it belongs, as a firstdivision heavyweight in the motor industry. Alas, it was not to be. For various reasons, mainly financial I expect, the plans for the new model fell through not long after it was originally announced. Who knows what the future holds now for this much-loved and missed motoring icon? For the time being, let us hope that Jensen owners continue to work on keeping their classic models alive and well, hopefully to pass on to the next generation of custodians.

Mark Dollery, Isle of Wight.

CHAPTER ONE

TWO INNOVATORS, ONE DREAM

The origins of Jensen Motors go back to the nineteenth century, when a second-generation Danish family decided to make a new life for themselves by emigrating to Britain. One of the sons decided to embark on his own shipbroking business, moving later into provisions importing. He was to be the father of two sons who would rise through the ranks to become highly respected captains of the British motor industry. Frank ‘Alan’ and Richard Arthur Jensen were born in Moseley, Birmingham, in 1906 and 1909, respectively. During their educational years they showed very little enthusiasm for schoolwork, with Alan regularly being at the bottom of the class, mainly due to a poor memory, and Richard spending most of the time sketching, the theme usually being motor cars! Right from the start, though, both brothers showed an interest in innovation, with Alan being involved with amateur radio and Richard being fanatical about maintaining and repairing his bicycle.

(Incidentally, the name ‘Jensen’ originates from the countries of Denmark, Norway and North Friesland. It means literally ‘son of Jens’, and is the most common Danish surname and ninth most common Norwegian. ‘Jens’ is the most common Danish and Frisian version of the biblical name Ioanne (John in English). There are three alternative spellings: in Danish and Frisian it is spelt like the car, ‘Jensen’; in Norwegian, ‘Jenssen’; and in English, ‘Jenson’. Perhaps the most famous English Jenson is Formula One racing driver and 2009 World Champion, Jenson Button.)

THE FIRST ‘JENSEN SPECIAL’

On leaving school, the brothers both started apprenticeships in their home town of Moseley. Alan was first assigned to the machine shop at Serck Radiators and gradually worked his way up to the drawing office. Richard, the keener motoring enthusiast, working on the more practical side of things at Wolseley Motors. The idea of the brothers building their own motor car came to Alan Jensen one spring evening in 1927, during a game of tennis at their local club, a pastime regularly enjoyed by both of them. Cecil West, a close friend of the brothers, turned up in a rather Heath-Robinson-looking affair that he had built himself. It was hand-painted patriotically in red, white and blue and fitted with a beaten-up old radiator from a Morris Cowley. Less than impressed with West’s creation, Alan none the less accepted a lift home from the tennis club and discovered that the car handled and performed much as it looked – it was dreadful, to say the least. When they arrived at the Jensen home in Bloomfield Road, engulfed in clouds of exhaust smoke, Richard came dashing out of the house to see what on earth was going on. After quickly casting his eye over the car, he came to much the same conclusion as his brother. On Cecil West’s smoke-filled departure, Alan is said to have turned to Richard to say, ‘If we couldn’t build a better car than that, then we ought to die in the attempt.’

Mr Jensen Senior strongly disapproved of the boys owning motorcycles, so, when they showed enthusiasm for owning a motor car instead, he very quickly offered to put down the money to make it possible. The car in question was a 1923 Austin Seven Chummy, registered OL 437, bought from a small local garage in town for £65. This was to be the platform for the Jensens’ first attempt at building a car of their own. It was collected one Saturday morning and driven straight back to Bloomfield Road, where it was put into a purpose-built workshop that had been erected at the side of the house. The first job was to remove the Austin body from its chassis, and by the end of that Saturday evening it had already been stripped down, ready to be re-clothed. After many hours of work, often burning the midnight oil, their creation was completed. Within a few months, using only very basic tools, the brothers had built an aluminium-bodied, two-seater sports model. The little car featured motorcycle-styled mudguard wings, full-width split windscreen, louvred side bonnets that were formed to fit against a 3-litre Sunbeam radiator and a boat-tail styled rear section, not dissimilar to that of the Type 35 Bugatti. Mechanically, the only modification carried out was the fitting of twin SU carburettors to the small 747cc fourcylinder engine, for more power. It was painted in green and retained the Austin’s original Birmingham registration number.

The first outing for the ‘Jensen Special’ was a memorable one for the brothers, for two reasons. Armed with just a basic tool kit in the back, they set off to a spectate at the well-known hill-climb at Shelsley Walsh. On the way there, one of the mudguard brackets broke, and the guard itself actually fell off into the road. Once the guard had been retrieved and the repair completed, they continued their journey to the hill-climb, only to be directed on arrival to the competitors’ parking area, rather than the spectators’! The organizers evidently thought that the brothers’ creation looked sporty enough to compete with the rest of the cars.

Before long, the ‘Jensen Special’ had received its first modification, in the form of restyled mudguard wings, which now flowed at an angle towards the middle of the car, incorporating short running boards. This was followed by an overhaul of the front suspension.

Jensen Special Number 1.

THE STANDARD PROJECT

One Saturday in mid-1928, whilst road testing OL 437 after its front-suspension overhaul, Alan Jensen had an encounter with Alfred Wilde, at that time the Chief Engineer at the Standard Motor Company in Coventry. It was to change the brothers’ lives for ever. Wilde had seen the little home-built car many times before but this time, impressed again by the sight of it, he hastily U-turned his Standard saloon and gave chase, beeping his horn and flashing his headlights until Alan pulled over. Wilde explained that he had been Chief Engineer at Standard since 1927 and that he had already designed the company’s successful new 9-horsepower saloon. He was looking for an opportunity to produce a sports variant based on a Standard chassis. Would the brothers be interested in designing a similar-looking body for a new sports model? He invited both of them to visit the Standard factory to discuss the project. When Alan returned home and told Richard of the chance meeting, it was quickly agreed that they could not turn down such a fantastic opportunity.

The brothers turned up for the appointment at Standard in their ‘Jensen Special’. Wilde and his engineers took a closer look at how the body was constructed and, once they had declared themselves satisfied with the quality of the work, the brothers were invited to select a running chassis for their build. The Standard 9 chassis was delivered to their garage in Bloomfield Road in July 1928, for work to begin at once on the new design. Because the Standard 9 chassis had a larger frame than that of the Austin, the brothers had an opportunity to build a more powerful-looking car, while still retaining the styling characteristics of the original ‘Special’.

Alan Jensen was still working at Serck Radiators, and was well placed to design and construct a unique and very striking-looking radiator for the new sports model. It was similar in design to the current offering from Standard, but was V-fronted in shape instead of being flat. Alan spent a considerable amount of the firm’s time, including overtime, developing it. This did not go unnoticed by his foreman, who eventually informed the management about young Jensen’s activities, resulting in an invoice to Alan for the sum of £21, to cover the cost of the materials that he had used to build the radiator. He was then summoned to see managing director Sydney Purchase in order to explain himself. Alan told him that he could not possibly afford to pay that amount of money and the story goes that Purchase looked him in the eye and said, ‘How will a nominal pound do, Jensen?’ Greatly relieved, Alan fled from the office.

‘Jensen Special No. 2’ (the first special was now referred to as ‘No. 1’) was first registered by Richard Jensen on 4 December 1928 as VP 4117. It was finally completed in February 1929 and painted in pale blue. The body panels were hand-formed in lead-coated steel over a wooden ash frame and power came from Standard’s 1153cc four-cylinder engine, with a three-speed manual gearbox.

Standard were very pleased with the brothers’ effort and, by August 1929, plans were drawn up for the prototype to enter production. It was not long before the car started receiving very encouraging magazine reviews, including one from Eric Findon of Light Car and Cycle Car and another from the then Midlands editor of The Autocar, Monty Tombs. Later photographic evidence shows that VP 4117 was modified into a two-/four-seater variant, featuring a reworked flat tail section with a flat windscreen and known as the ‘Jensen Special No. 3’.

Alfred Wilde was also in charge of the car’s production process and he soon decided that the construction of the bodies was to be contracted out to the nearby Warwickbased New Avon Motor Body Company. The reasoning behind this was quite simple: New Avon at that time was run by John Maudslay, who just happened to be the son of the Standard Motor Company’s founder and chairman, Reginald Maudslay.

Jensen Special Number 3, clearly showing the revised mudguard arrangement, flat windscreen and tail design.

STANDARD REGISTER

For production purposes, the ‘Jensen Special No. 2’ underwent some minor changes regarding mechanical specification, including raising the compression ratio of the 1153cc engine, the fitting of an SU carburettor, a lower axle ratio and rear springs, a modified radiator and exhaust system, along with revised instrumentation and altered steering column rake. Designated as the Avon Standard Special Sports, the first models were ready for dispatch by October 1929. By this time, Alan Jensen had left Serck Radiators and joined New Avon in a supervisory role to oversee the build process of the bodies. Richard had moved on from Wolseley Motors to work for Lucas, the manufacturer of automotive electrical components.

Production continued throughout 1930, with Alan constantly working with Standard’s own designers and even Wilde himself, making improvements to various styling features. They even designed a similar body to fit on to Standard’s larger, nine-point-nine horsepower chassis, which used a bored-out version of the 1153cc engine. Now 1287cc, it was also used in their new ‘big’ Nine, which was introduced in August 1930. Unfortunately though, the end of 1930 brought tragic circumstances for the Standard Motor Company, with the death of Alfred Wilde on Christmas Day, the cause being a heart attack due to a combination of malignant flu and overwork.

Back in late 1929, Standard had introduced their much larger Sixteen model, powered by a 2054cc six-cylinder engine. But it was not until a year later that the Sixteen chassis would be clothed with coachwork designed by Alan Jensen, which featured Swan coupé and open-tourer bodies. These designs were improved upon for 1931 – on the Swan coupé, this included shortening the bonnet area, making the interior more spacious to allow for the fitting of an occasional rear seat. The idea was that the seat could also be folded forward in order to increase the size of the boot compartment; tough rubber matting covered the rear of the backrest to allow for this. Wind-down windows with safety glass were also fitted, along with a sliding sunshine-roof, electric windscreen wipers and an improved ‘twin-top’ four-speed gearbox, which replaced the previous ‘crash’ unit with synchromesh in third and fourth gears. Also in 1931, Standard introduced a model called the ‘little’ Nine – a baby version of the ‘big’ Nine, with power coming from a much smaller, 1005cc four-cylinder engine. In the meantime, having been out of the limelight for a while, Richard Jensen was desperately craving the opportunity to design and build another car with his brother. It was his friend Arthur Clackett who would be responsible for bringing the two of them back together again.

AVON MOTOR BODY COMPANY

Founded in 1919 by Mr Tilt and Captain Phillips as the Avon Motor Body Company, for the first ten years the business concentrated solely on building specialist bodywork for the motor manufacturer Lea-Francis. In 1922, it was renamed as the New Avon Motor Body Company and, in 1929, also started building bodies for the Austin Motor Company, while at the same time developing a contract with Standard that would last for the next ten years. In 1938, New Avon was renamed Avon Motor Bodies Ltd and became part of the Maudslay Motor Group, which had been founded by Reginald Maudslay’s father, Walter H. Maudslay. It also moved to larger premises at Ladbroke House, Millers Road, Warwick, where it would remain for the next fifty years or so. After the war, John Maudslay retired, to be replaced by one of the company’s directors, a Mr Watson, who steered away from the coachbuilding side of the business and started focusing more on undertaking body repairs of standard-built vehicles, which continued well into the 1970s.

In 1973, the company was sold to Graham Hudson, who wanted to expand by combining New Avon with his own already thriving Volvo agency and body repair business. Already well aware of New Avon’s coachbuilding past, he planned to revert to producing specialist bodywork for other motor manufacturers and, by 1978, Ladbroke Avon Ltd incorporating Avon Special Products was formed. Initially, the new company produced a series of converted Land Rovers and Range Rovers, but their most memorable conversion was, without doubt, the beautiful Avon-Stevens Jaguar/Daimler XJC convertible, named after its designer Anthony Stevens. It was basically a standard-specification Series 2 two-door XJ-coupé with the roof removed and replaced by a manually operated vinyl hood, lined inside using ‘West of England’ cloth.

In 1980, the convertible was joined by an estate version, again designed by Anthony Stevens, which was based on Jaguar’s Series 3 of the time. The design was not particularly graceful, to say the least, but it was very practical, offering 35cu ft of luggage space with the rear seat in place and more than 58cu ft when it was folded down. The estate’s tailgate was also very cleverly devised and this was achieved by grafting a Renault 5’s rear hatch frame on to the vertical boot panel of the XJ, with rear ventilation grilles being sourced from the Renault as well. When launched at the 1980 Motor Show in Birmingham, the XJ-estate won Avon the gold award in the international coachwork competition – praise indeed. The XJ-estate conversions continued through to 1981, but by then, Graham Hudson had decided to move towards the less luxurious end of the market by offering high-specification versions of the newly launched Triumph Acclaim.

PATRICK-JENSEN MOTORS

In 1930, Arthur Clackett introduced Richard to a certain Joe Patrick, who at that time was running a firm called Edgbaston Garages Ltd, based on the Bristol Road in Selly Oak, Birmingham. The business was actually owned by Joe’s father Albert, who had recently purchased the garages for Joe to take on the day-to-day running. Like the Jensen brothers, Joe was a very keen motoring enthusiast and had been following their work, in particular Alan’s more recent designs that he had been creating at New Avon. The outcome of the meeting was that Joe Patrick offered Alan and Richard a position with the firm, so they could once again combine their creative ability in producing coach-built bodies.

They both accepted the offer and, once Alan had left New Avon and Richard had left Lucas, work started immediately on reorganizing the garage. A coachbuilding department was set up, along with a service centre that was open in the evenings, and on Sundays too. It was not long before the brothers’ first creations were being offered – variations on Wolseley’s little Hornet model. In September 1930, with Alan and Richard having now joined the board of directors, Edgbaston Garages Ltd was renamed Patrick-Jensen Motors Ltd.

Unfortunately, the Jensens’ time at the firm would prove to be a short and turbulent one. They were often, it seems, embroiled in boardroom clashes with the other directors, but it was one particular incident that eventually sealed their fate. Joe Patrick overheard a conversation between two of his most valued customers, with one asking the other if he knew the Jensen brothers very well. Apparently, the other replied, ‘Oh yes, I know one of them well enough to call him Pat.’ Naturally, Joe was not amused at this remark and immediately called for a board meeting to be held the following morning. After a rather angry discussion, both brothers ended up resigning from the company and left that afternoon.

That was in March 1931. After the brothers’ departure, the business was renamed Patrick Motors Limited and continued producing the Wolseley specials, now under its own name. By 1934, Joe Patrick had expanded the business to offer affordable coach-built specials on Austin, Ford, Rover, Singer and Triumph chassis as well. The expansion plan also involved the development of the sales and service side of the business, with sites opening in Birmingham’s city centre and on the outskirts, in the town of Olten. After the war, a subsidiary company called Patrick Aviation was set up, to carry Midlands-produced goods to various destinations throughout Europe. It operated a daily scheduled service from Elmdom aerodrome – better known today as Birmingham Airport – but it was relatively short-lived because, in 1953, British European Airways (BEA) took over all the scheduled routes.

The motor business continued to expand, now known as Patrick Motors Group (PMG), and acquiring such prestigious dealerships as Reeve and Stedeford, the Solihull agents for Jaguar/Daimler, Spink of Bournemouth and Westover Motors. Gradually, PMG started retailing many other marques such as Mercedes-Benz, Vauxhall, Peugeot/Talbot, Isuzu, Subaru and Toyota, with the main brand always being Austin-Rover. In 1982, Joe Patrick died. This loss, along with the increasing demands that were being placed on the business by the motor manufacturers, led to the eventual demise of PMG. The last dealership to be sold off was Mercedes-Benz at Patrick Solihull, in 1999.

SMITHS

After hearing about the Jensens’ break-up with Joe Patrick, an ex-work colleague of Richard’s came to the rescue. John Hathaway, who had been an apprentice with Richard at Wolseley, happened to know the son of a large provisions merchant called George Mason, whose father also had an interest in an already well-recognized West Bromwich-based coachbuilding firm by the name of W.J. Smith and Sons. Mason senior, also named George, owned a chain of grocery stores throughout the Midlands and Smiths were responsible for, among other things, building the bodies for all his delivery vans. Mason had, however, been less than impressed by the workmanship on offer at Smiths; Hathaway’s idea was that the Jensen brothers might be able to join the company and sort things out. Smiths offered the sort of opportunity that the Jensens were looking for, and eventually it was decided that both brothers would also come on board as Joint Managing Directors.

One of the problems concerning Smith’s poor quality control at the time was the fact that, although the workforce were highly skilled, the tooling had become somewhat outdated and, in some cases, had even been allowed to fall into disrepair. The method used to make the van bodies was also dated, more appropriate to the days of horse-drawn carts. Alan was immediately tasked with updating the tooling, re-designing some of it, while also introducing more modern techniques for manufacturing and assembling the bodies. One good example of the inefficiency in the workshop was in the drilling of the holes for the chassis bearers, which were made from 9in solid timber. Using a simple hand-brace, the workforce would first have to pierce through the timber with a drill bit, then, to make the holes large enough for the bolts to fit, a rod was driven down them. The rod had to be heated until it was red-hot. Two problems arose from this method: first, the holes more often than not were bored off-centre and, second, the heating of the rods caused the workshop to be constantly filled with a horrible blue smoke. Alan Jensen’s answer to this was to mount a motor-driven drill on a specially designed portable frame made out of angle iron. This not only allowed an accurately drilled hole to be produced, but also cut the labour time.

Apart from Smiths’ delivery van contract with George Mason, they were also busy producing lots of other custom bodywork for all types of customers built on various chassis. This included lightweight tipper trucks, flatbeds, dropsides, pantechnicons, small tanker lorries and even single-decker buses. Smiths had first started coach-building bus bodies back in 1914, when they built a twenty-five-seater, based on an Albion chassis for the local West Bromwich Corporation. By the time of the arrival of the Jensen brothers, the firm had just completed an order for another five bodies that were built on Dennis HV chassis, for the same corporation. This was soon followed by a twenty-seater on a commercial Morris chassis, which joined the fleet in 1933, along with another two thirty-eight-seater bodies on a Dennis Lancet chassis for the following year. A further four thirty-nine-seater bodies were built on Dennis Lancet II chassis for 1937, with another three thirty-eight-seaters on Daimler COG5/40 chassis, an order which ran until the outbreak of the Second World War.

The time at Smiths was the brothers’ first venture into producing coach-built bodies for commercial vehicles and, in these early days, this activity was to remain the mainstay of the business until car production finally took off in the mid-1950s.

William Smith, the man that had started all this, continued in the workshop on a part-time basis for a while until he eventually retired, in 1932. He spent the remainder of his days in the Channel Islands until his death the following year at the age of 88. As for Alan and Richard Jensen, they continued on in the business where Smith had left off, with Alan continuing to make improvements to the manufacturing process whenever he could. It was to prove to be a valuable experience in what was to become a dream come true for two innovative and industrious young men.

Alan Jensen.

JOC

Richard Jensen.

JOC

THE STORY OF SMITHS

The founder of W.J. Smith and Sons was a William James Smith, who was born in the county of Leicestershire in January 1845, the son of James and Mary Ann Smith. He spent the very early years of his life in the city of Leicester but, around 1850, his father decided to move the family up to the county of Nottinghamshire, where his brother Henry Charles was born. At some time between 1851 and 1860, the Smiths relocated once again, this time to the Isle of Wight, where James Smith had been born. They settled in the seaside resort town of Sandown and James became a barman at a local public house.

In January 1861, aged sixteen, William started work as an apprentice coachbuilder for the Island-based firm Chas. Midlane (‘Coach, Carriage, Spring Van and Light Cart Builder Painter and Trimmer’), situated at Deadman’s Lane (renamed Trafalgar Road at some time between 1859 and 1862), in Carisbrooke village in the capital of Newport. Deadman’s Lane was so called not only because it was a former site of many a public hanging, but also because it was the burial ground of the soldiers who died during a great battle against the invading French Army in 1377. It led to Kings Field, today known as Node Hill, named after the dead bodies, or ‘noddies’, or as they were then called. The precise location of Midlane’s workshop is difficult to pinpoint, but it seems that, at the time of William Smith’s employment, the address was 19 Trafalgar Road, on the south side, somewhere near the junction of Nelson Road and Carisbrooke Road. By 1888 or 1889, number 19 had been taken over by E. Winscom and Company, which made tea deliveries, with Midlanes having relocated to two new addresses: 31 Trafalgar Road, about half-way along on the same side; Midlane’s Coach Factory was located between H.W. Morey and Sons, the timber, slate and cement merchant, and the private residence of number 72 on the north side, not far from the junction of Upper St James Street. Of course, during the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s a great deal of the numbering system was changed due to the fact that many new houses were being built, which has made locating these historic sites even more difficult.

On 23 October 1866, William Smith married twenty-two-year-old spinster Caroline Fanny Allen, at the Parish Church in Sandown, and in 1867 Caroline gave birth to a son, who was also named William James. After finishing his apprenticeship and gaining some experience at Midlane’s, around 1870, William and Caroline decided to move up country and set up their own business at 377 High Street, Carters Green, in West Bromwich.

In 1910, the business ran into financial difficulties and was bought out by three brothers by the name of Roberts, who already owned a garage repair business in Bratt Street. Brother Fred took on the running of the business and, by 1920, he had completely rebuilt the workshop and showroom. William Smith was still working there, but on an employed basis as their estimator, along with his son William junior, who was on the shop floor as a coachbuilder. Around 1923, trouble struck again, with Fred Roberts having to liquidate the business and sell the premises to a property investor by the name of Bob Holyland from Walsall. Holyland auctioned all the remaining stock and then rented the site out to a Frank Guest and also William Smith. Guest ran a local Ford agency and wanted the showroom for expanding his dealership, while Smith stayed on and ran the workshop with his son. Later, after much persistence, Guest finally bought out Smith’s share of the business. Although now well past retirement age, Smith still wanted to be involved in the motor trade, so he ended up purchasing some land at the rear of the workshop on which he could build and run his own purpose-built garage. This was this site at Carters Green that would eventually become known as Jensen Motors Ltd.

CHAPTER TWO

THE PRE-WAR V8, STRAIGHT-EIGHT AND V12-CYLINDER MODELS 1934–1941

EARLY RE-BODYING PROJECTS

With the Jensen brothers established at W.J. Smith and Sons, Richard had the opportunity to utilize some vacant factory floor space. This enabled him to concentrate on producing custom bodywork for other motor manufacturers on their existing chassis, leading to the eventual building of true Jensen production sports cars. The brothers’ very first venture into re-bodying other manufacturers’ chassis is a bit vague, but it seems they started by building oneoffs for any customer who came their way, possibly beginning in 1931 with an upmarket, high-performance machine called a Moveo. Powered by a Meadows 2973cc six-cylinder engine, the car’s chassis had been designed by Bert Houlding of Preston, in Lancashire, and was produced to a very high standard. Jensen’s offering was a long, sleek two-door, four-seater coupé with a fabric-covered sunshine roof and luggage container.

Plans were drawn up for the building of another two Moveo machines for Houlding but, alas, this venture for the two enthusiastic brothers was not to be a success. Unfortunately, when Houlding saw the Jensen conversion he criticized the design for not being sporting enough and that marked the end of any further work between them.

After the ill-fated Moveo contract, the Jensen brothers continued undeterred until the outbreak of the Second World War, carrying out various body conversions for any independents. These included the tuning specialist Michael McEvoy, with his performance-enhanced Wolseley Hornets, and Ron Horton’s famous, Brooklands-winning MG ‘C’ Type Midget and Magnette K3 offset streamlined-bodied racing cars. The latter were quite unique, based on the concept that the car would give the best possible handling when raced on the steep, left-handed oval banking at Brooklands if the body was located offset to the right-hand side of the chassis.

The brothers carried out further one-off conversions, with increasing success as far as customer satisfaction was concerned. In 1932, they worked on another Brooklands racing car, this time for amateur racing driver Neil Gardiner, who wanted his Delage 2 racer converted into a closecoupled coupé for road use. A special roll-top coupé body was built for Carl Skinner, who at the time was an associate of the brothers and ran the SU (Skinner Union) Carburettor Company. Powered by an American 4162cc, straight-eightcylinder Hudson Essex-Terraplane engine, and fitted with four of Skinner’s own SU carburettors, the chassis was built as a one-off by the firm Rubery Owen, whose name would feature again soon in Jensen’s history, as well as some decades later.

As time went on, other coachbuilders became keen to employ the Jensen brothers’ skills in bodywork conversion. London-based car dealers Pass and Joyce Ltd, who specialized in manufacturing distinctive bodies on Darracq, Sunbeam and in particular Talbot chassis, contracted them to build a special two-door drop-head body on an American Chevrolet Master six chassis. Although the circumstances of the car’s origins are unclear, it seems that this Jensen-Chevrolet was eventually offered for sale through their own dealership.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!