9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

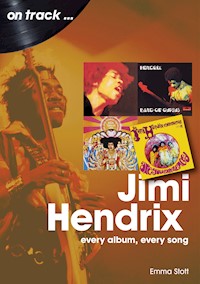

- Herausgeber: Sonicbond Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: On Track

- Sprache: Englisch

The legendary Jimi Hendrix has had all kinds of superlatives bestowed on him since his incendiary debut in 1966, but Lou Reed’s pithy summation beats the lot: ‘…he was such a bitching guitar player’.

Jimi Hendrix On Track explores each thrilling song and album, drawing out exactly what made Hendrix not only a great guitarist but also a vocalist, arranger, interpreter, producer and songwriter of genius.

Hendrix’s revolutionary albums with The Experience and Band of Gypsys are discussed in detail, as are his posthumous releases from First Rays of the Rising Sun to Both Sides of the Sky. His early work as a session player for acts like The Isley Brothers, Little Richard and even Jayne Mansfield is considered, along with his later work as a guest star on albums by Stephen Stills, Robert Wyatt, and McGear and McGough, and not forgetting his blistering work as a producer for Eire Apparent.

From psychedelic odysseys to progressive blues to proto-metal to funk-rock, Hendrix mastered them all. Jimi Hendrix On Track is an informative guide to some of the 20th century’s most extraordinary recordings.

Emma Stott missed out on the 1960s and the 1970s and she still isn’t over it, so writing about the greatest decades in rock music helps with her loss. She also writes about literature and education, being an English teacher by day in Manchester, UK, where she forbids any ‘dark sarcasm’ in her classroom.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 318

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Sonicbond Publishing Limited

www.sonicbondpublishing.co.uk

Email: [email protected]

First Published in the United Kingdom 2022

First Published in the United States 2022

This digital edition 2022

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data:

A Catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Copyright Emma Stott 2022

ISBN 978-1-78952-175-7

The right of Emma Stott to be identified

as the author of this work has been asserted by her

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Sonicbond Publishing Limited

Printed and bound in England

Graphic design and typesetting: Full Moon Media

I ain’t finished yet, brother… I got more to say.

Jimi Hendrix

With love and thanks to my other favourite guitarist, Dad.

Contents

Introduction

The Are You Experienced Singles

Are You Experienced (1967)

Axis: Bold As Love (1967)

Electric Ladyland (1968)

Band of Gypsys (1970)

The Jimi Hendrix Experience (Box set) (2000)

First Rays of the New Rising Sun (1997)

South Saturn Delta (1997)

Valleys of Neptune (2010)

People, Hell and Angels (2013)

Both Sides Of The Sky (2018)

Live Roundup

Compilations

Guest Appearances

Afterword

Introduction

Curiously, for an act who omitted the question mark from the title of their ground-shaking debut Are You Experienced, The Jimi Hendrix Experience were a band of powerful punctuation – guitar work that declared, interrogated and exclaimed; drumming that bracketed and divided like commas, and bass lines which pounded out intriguing ellipses. And that’s what really testifies on each listen. The threadbare cliché that Jimi Hendrix made his guitar speak, really misses the point: Hendrix himself speaks, coaxes, boasts and teases in an unmistakeable baritone, but the guitar gives it meaning. Think of the question-exclamation riff that announces ‘Purple Haze’; the asterisk-ampersand frustration and ecstasy of ‘Foxy Lady’s’ explosive solo; the big interrobang of ‘Can You See Me?’

In 1966 – the year Hendrix began recording in London – the French author Hervé Bazin created six new types of punctuation, consisting of marks for love, acclamation, doubt, irony, authority and conviction. Hendrix was doing the same for the guitar, developing bends, trills and vibrato that would give new intention to song. Progressing beyond the biff-bang-pow of garage and the po-faced purity of blues echoists, Hendrix’s music has flares of pop art’s punctuation, knowingness and an appreciation for the ready-made; even a measured banality and, similarly, he drew on American and British influences, eschewing elitism. In the extraterrestrial ‘3rd Stone From The Sun’, the very terrestrial cobbled stones of the Coronation Street theme are resounded; numerous songs include Hendrix clearing his throat; Rover the dog is name-checked; Superman becomes a motif of ironic masculinity. For someone feted to be extraordinary, the ordinary often peeps through. Yet, at the same time, the notes that splash, splurge and splatter from his Fender Stratocaster evoke abstract expressionist canvases, with ‘strange, beautiful’ patterns in the crafted chaos.

If his guitar did speak, it wasn’t in any existing language, but was formed of borrowings, coinages and intonations of remarkable force. The Creation’s guitarist Eddie Phillips (The Creation gave ‘Hey Joe’ a try in 1966 too) declared their own music to be ‘red with purple flashes’, but Hendrix’s sound is purple, with gold, rose, misty blue and lilac radiation.

At the risk of sounding trite and nostalgic, much of the music of the 21st century seems to be looking neither back nor forwards and is strangely neutered. Little seems to acclaim; to doubt, to love. And who is creating a new musical language? Hendrix’s guitar sound remains synesthetic, leaving a shadow of texture and colour and flavour. In ‘Love Or Confusion’, Hendrix asks: ‘Must there be all these colours/Without names, without sound?’ He gave them sound. The sound gave them meaning. And he did it with only a handful of albums.

Jimi Hendrix

It seems like a sort of nominative destiny – four years after Hendrix’s birth (27November 1942 in Seattle, Washington), his father Al altered Hendrix’s first names from Johnny Allen to James Marshall. James Marshall Hendrix: a man who would challenge the world through his Fender guitar and Marshall stack. After a somewhat nomadic childhood (Hendrix and his brother Leon lived with various relatives after their parents’ divorce, whilst his father struggled to find work), Hendrix would undergo other name changes as he strived to build a musical career. Firstly, he was Private Hendrix when he spent a year in the 101st US Airborne Division in California. Reportedly obsessed with his guitar, Hendrix was a distracted and uncommitted paratrooper, and it’s likely that his discharge over an ankle injury was highly convenient and probably apocryphal. It’s rumoured that Hendrix faked mental illness and homosexuality to get himself thrown out, such was his antipathy towards being a soldier. Nevertheless, his time in the army did bestow two blessings – he experienced 26 parachute jumps: a feat that must’ve contributed to the vertiginous lyrics and soundscapes to come. He also met his future bassist Billy Cox, who would play with Hendrix in the army band The King Kasuals, contribute to Hendrix’s first recording session in 1962, and later be part of the Band of Gypsys.

In 1964, after gigging around the Chitlin’ Circuit (a problematic and divisive term taken from the dish of chitterlings – pig intestines – a meal frequently offered to black people in place of finer cuts; the term referred to venues that welcomed performers of colour at a time of racial segregation), Jimmy Hendricks backed the Isley Brothers, adding irrepressible guitar to their joyously unrestrained ‘Testify (Parts 1 and 2)’: ‘So glad I got some soul, woo!’. The track also declared, ‘I know James is a witness/Go ahead James and testify!’ Despite this being a name-check for James Brown (Stevie Wonder – who later jammed with Hendrix – and Jackie Wilson are invited to testify too), it seems to predict the musical avowals to come from Hendrix himself. He can also be heard on the Isley Brothers’ energetic ‘Move Over And Let Me Dance’, developing the polyphony he would later master, though his scribbly trills are lost behind the dogmatic brass. Another song that came in two parts like ‘Testify’ was Ray Sharpe’s ‘Help Me (Get the Feeling)’ – Hendrix brought it a tight rhythmic riff, but was again overpowered by the horns. Unfortunately, the song’s first part fades out just as the trim solo begins. ‘Part 2’ fades in on this and reveals it to be an almost shy performance. Nevertheless, the song has the vibe of Them’s ‘Gloria’, which Hendrix would later cover with some outright rude and crude playing and singing!

Unsurprisingly, there then came a stint backing Little Richard (later, Reverend), under Hendricks’ new moniker Maurice James. His snaking riffs can be heard on ‘It Ain’t Watcha Do (It’s The Way How You Do It)’, which has a shiver of ‘Gypsy Eyes’ from Electric Ladyland. The lines ‘Well, if the shoes don’t fit you/You better not force it’ could apply to the combination of two of rock’s most flamboyant figures sharing a stage. Little Richard was said to be annoyed – even threatened – by Hendrix’s ostentatious dress and stagecraft. Notwithstanding, Hendrix backs him with unassuming guitar on the rueful ‘I Don’t Know What You Got, But It’s Got Me’, where Richard sing-speaks in a way that his guitarist would later adopt. ‘Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On’ is Hendrix’s messiest recording, with lots of ideas, from bends to trills to runs, but none of them executed cleanly. Nevertheless, Little Richard said of him in a 1973 documentary: ‘At times, he used to make my big toe shoot up in my boot… he didn’t mind looking freaky.’

However, Little Richard did seem to mind this, and by the end of the year, Hendrix had moved on and was playing with Curtis Knight and the Squires, but not before a curious detour that found him providing backing to cuts by actress Jayne Mansfield – star of the rock ’n’ roll vehicle The Girl Can’t Help It, which also features an exuberant Little Richard. Mansfield’s ‘As The Clouds Drift By’ cannot exactly be deemed a hidden gem, but in truth, is no worse than many frothy ballads of the time, and its dreamy minor-key fade-out is not a million miles from later floaty psych tracks. Its B-side – co-written by Hendrix’s first manager Ed Chalpin – is daft and jazzy in faux beatnik style à la Miss X’s ‘My Name Is Christine’: ‘It makes my knees freeze/It makes my liver quiver!’ The slick guitar licks and jumpy bass lines (both supposedly delivered by Hendrix) promise the more symbolist playing to come.

In Jimi Hendrix and the Making of Are You Experienced, Sean Egan writes: ‘The various musical adventures in which he took place (before forming The Experience), comprise the most inauspicious preamble’. This is an overstatement. Like The Beatles and indeed Led Zeppelin, Hendrix had to serve as a novice, and his varied apprenticeship made his music all the more kaleidoscopic. It cannot be asserted that anything pre-Experience is its equal, but there are enough highlights to make seeking out these tracks worthwhile. It also challenges some of the hyperbolic discourse that sets Hendrix as a sui generis phenomenon. In truth, that doesn’t elevate his brilliance, which he strove to achieve, but rather removes it from the man and his own experience. He was undoubtedly remarkable, but as has previously been stated, was also a man within as much as without his times. Furthermore, Hendrix was not only an innovator in terms of composition, but was an interpreter of genius. It is hard to deny that two cover versions (‘All Along The Watchtower’ and, yes, even ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’) rank amongst his most significant, powerful and famous accomplishments. Whilst nowhere near his greatest work, ‘Hey Joe’ is nevertheless an astonishing and encouraging interpretation. A man removed from his context would not have been as sensitive, knowing or responsive enough to put forth these recreations.

Where The Beatles’ covers – and even those of The Rolling Stones – are frequently the least interesting cuts of their oeuvre, there is a compelling argument that Hendrix’s reworkings are part of his quintessence, and certainly of his legacy. Would he have been as adept an interpreter without supporting other acts? And if we’re looking for inauspicious beginnings, then his predictable first live set with The Experience seems even less remarkable: ‘Land of 1000 Dances’, ‘Midnight Hour’, ‘Mercy, Mercy’ and ‘Hey Joe’. Yet these songs would inform his own writing and playing beyond the Experience and all the way into Band of Gypsys and beyond.

Returning to Hendrix’s stint with the Squires, we have him lending restrained support to the pleasant instrumental ‘Station Break’: a menacing riff to the buzzy Dick Dale-esque ‘Hornet’s Nest’ (where on this Hendrix co-write, his guitar and Nate Edmonds’ organ, work particularly well together, giving a little promise of ‘Voodoo Chile’), whilst ‘Gloomy Monday’’s fusion of pop, soul and rock showcases Hendrix on assured backing vocals too. But this work is still embryonic, and the newly named Jimmy James now formed his own band: The Blue Flames. But previously to this significant step forward, Hendrix also appeared on another important track: ‘Mercy, Mercy’ by Don Covay. Covay had worked with Little Richard and would go on to write for Aretha Franklin. Hendrix’s guitar-playing is understated (as is his contribution on a less successful Covay track ‘Can’t Stay Away’) but has a suitably pleasing tone that gives the song its character and would be partly revived for Hendrix’s own ‘Remember’. The song also opens with a rueful but ear-catching riff, and Hendrix would develop this for ‘Hey Joe’. Furthermore, the song so impressed Stax guitarist Steve Cropper that he recorded a version with Booker T. & the M.G.’s, and asked Hendrix to show him how he’d played it. Don Covay and the Goodtimers’ version of ‘Mercy, Mercy’ (sometimes known as ‘Have Mercy’) became an instant R&B standard, despite only reaching number 35 on the Billboard chart, and The Rolling Stones covered it on Out Of Our Heads. It was to be a bridging song for Hendrix; one he performed with the Squires, The Blue Flames and during Mitch Mitchell’s audition for The Experience and at some of their early gigs.

The Blue Flames started out as a trio with bassist Randy Palmer and drummer Dan Casey, performing a blend of blues, pop and soul. Intriguingly, a second guitarist was added: future Spirit member Randy California, who impressed with his slide playing. Rumour has it that Hendrix would later feel upstaged by some of California’s performances and, subsequently, California turned down Hendrix’s invitation to join him in London. Yet other sources attribute it to California’s parents considering him too young to go, which seems the likeliest story as he was only 15. Regardless, California learnt much about distortion from Hendrix, and would later cover ‘Red House’ and ‘Look Over Yonder’. Hendrix nicknamed him California because of the other Randy in the band: Randy Palmer, who became Randy Texas. However, Randy’s given name was the unfortunate Randy Wolf – sounds almost like the title of a Hendrix track! We can get a sense of how The Blue Flames were looking more towards Hendrix’s future sound in this reminiscing by Bob Kulick: sometime guitarist for Kiss, Alice Cooper, Meat Loaf and Diana Ross. He told Classic Rock:

In 1966, I was 16, and my band The Random Blues Band, played at the Café Wha? club in Greenwich Village. One day we were told this guy was coming down to audition, and the name of his band was Jimmy James and The Blue Flames. So we watched as this guy came in and started to set up his gear. He was asking about using two amp cabs together, and we all looked at each other like, ‘What? How do you do that?’ On stage, he had all these pedals, and I thought, ‘This should be interesting.’ He had a very interesting look. He looked like a star. The band started playing what sounded like a prototype of a ‘Third Stone From The Sun’ kind of song, and within one minute, you knew that the guy wiped the floor with everybody we’d ever seen play. By the end of his set, when he played solos with his teeth that nobody could play with their hands, we knew this guy was a sensation.

The Blue Flames’ take on Bo Diddley’s ‘I’m A Man’ displays Hendrix in a lower, growling register, but complete with ironic ‘Look out babies’ to announce its spiky solo. By then, they were a quintet with guitarist and harmonica player John Hammond swelling the ranks. It was this group that The Animals’ bassist Chas Chandler watched perform ‘Hey Joe’ at New York’s Café Wha? in the summer of 1966 after Linda Keith’s persistent recommendations: astounded, Chandler subsequently offered to manage Hendrix. One of the first questions Hendrix asked Chandler was if he knew Eric Clapton. Indeed, Chandler felt his friendship with Clapton – and his promise that Hendrix would impress Clapton much more than the other way around – was what really convinced Hendrix to fly to England and accept Chandler’s offer.

Lamentably, Hendrix had previously committed to a deal (in 1965) with Chalpin’s PPX Enterprises for exclusive recording rights. But in the excitement of becoming Jimi Hendrix – and a month later, The Jimi Hendrix Experience – this was forgotten.

The Are You Experienced Singles

Legend has it that Hendrix settled on his final and most famous moniker on the plane flying to Britain. An airborne baptism does indeed seem fitting. The Experience tag has been attributed to Chas Chandler, or sometimes to Mike Jeffery: The Animals’ manager who co-managed Hendrix with Chandler. Jeffery would be killed in a mid-air collision in 1973, but his troubling reputation has endured, with allegations of financial mismanagement, punishing work schedules, a bizarre kidnapping of Hendrix, and even involvement in his death. Whilst some of these claims are unsubstantiated, condemnation of Jeffery has been consistent from Hendrix’s bandmates, friends and biographers over the years. Many of these biographers have also sometimes taken exception to what they consider to be sexist Hendrix lyrics, yet it’s hard not to consider that the guitarist’s yearning to be ‘stone free’ might often have had more to do with Jeffery’s restraining deals that tethered Hendrix’s career than outright misogyny.

Yet Hendrix was blessed by Chandler’s support, and he was to step away from managing Hendrix to focus on producing him, meaning Chalpin was necessary. Chandler, too, has sometimes been described as tyrannical, and the dual roles of producer and manager usually do result in the artist feeling constrained (see also The Rolling Stones and Andrew Loog Oldham), but Chandler’s discipline, tenacity and professionalism undoubtedly helped to realise the Experience’s sound. Furthermore, he also coached Noel Redding in bass techniques and encouraged Hendrix to use his voice rhythmically and confidently. Another boon was the involvement of Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, who set up Track Records to provide a label for Hendrix, and would allow him his greatest creative freedom so far.

When Hendrix arrived in England, he not only desired a sympathetic label, but he also needed a band. Curiously, Chandler first tried out Hendrix with organist Brian Auger, who introduced him to Marshall amps. This is a tantalising idea – as Hendrix might have gone on to develop his sounds with piano and organ augmentation – but surely, two lead players of such potency would neutralise each other. As this wasn’t to be, Chandler and Hendrix then began to seek musicians to form a band with Hendrix, although at this stage, it still wasn’t decided whether Hendrix would be the singer or frontman.

There were two likely candidates for drums: Mitch Mitchell and Aynsley Dunbar. Dunbar had played for The Mojos and would go on to work with John Mayall, Frank Zappa and David Bowie. The story goes that Dunbar lost on the toss of a coin.

Ealing’s Mitch Mitchell had picked up his drumsticks after a career as a child actor and had worked in Jim Marshall’s (he of the amplifier) music shop. Despite Mitchell’s contribution being underplayed at times, he features in Rolling Stone’s top 10 drummers, with Queen’s Roger Taylor commenting insightfully that Mitchell played ‘riffs’. Notwithstanding, being barely 20 when he met Hendrix, Mitchell had played with numerous acts, including The Pretty Things, The Riot Squad and The Who. His rock and pop experience was augmented with jazzier influences by backing Georgie Fame and then joining The Soul Messengers, who included a saxophonist. Playing with an instrument of such sustain proved effective rehearsal for complementing Hendrix’s fluidity.

Completing the trio was Noel Redding, whose first instrument had been the Jew’s harp, and his first song was the murder ballad ‘Tom Dooley’, which recounts a knife killing to parallel the crime passionnel of ‘Hey Joe’. Redding then moved on to the violin, the mandolin and finally the guitar, though he would be nudged on to bass for the Experience. He gigged around with The Lonely Ones before enjoying a stint with The Loving Kind, releasing the non-charting ‘Love The Things You Do’. As Redding was auditioning for The New Animals, Hendrix admired his use of blues techniques (and his impressive hair!) and offered him a place alongside Mitchell. Despite being dismissed at times as the luckiest backing band in rock, Mitchell and Redding were crucial additions, with Keith Shadwick explaining in the compelling Jimi Hendrix: Musician that Hendrix thought ‘Mitchell was Elvin Jones… Redding was his Jimmy Garrison’. Garrison and Jones were jazz musicians who worked with John Coltrane, amongst others. Perhaps this overstates Redding’s skills a little, but his playing is often suggestive rather than merely rhythmic, with something of Garrison’s good taste; Elvin Jones’ rich timbres certainly influenced Mitchell’s sound and technique. Chandler put it more succinctly and pragmatically in the The Making Of Are You Experienced video: ‘That’s what delivered the money. Them three.’

Within a few weeks, The Experience had recorded their first single, ‘Hey Joe’. Buoyed by performances on Ready Steady Go! and Top of the Pops, it peaked at number six in the charts. In between touring, Hendrix was working on his original compositions: ‘Hey Joe’’s self-penned follow-up ‘Purple Haze’ was released in the spring as the trio were working on their debut collection. Are You Experienced soared into the charts in the middle of May 1967, just as the Summer of Love was blooming. But the album was more than a change of season: it was an electric manifesto that galvanised fans and peers; its aftershocks are still being felt. All this from an album that took around ten days to record and cost approximately £1,500.

Yet some weren’t ready to be experienced. The album was met with criticism of both the music (though revealingly not of Hendrix’s playing) and lyrics. And even Hendrix himself was already frustrated by how he was being represented. The UK album cover caused him some misgivings too, and indeed the US version is superior. The UK visual shows Mitchell and Redding peering from Hendrix’s cloak like Ignorance and Want in A Christmas Carol. Aside from being unintentionally comical, it does seem to sideline the musicians in a way that Hendrix himself never did: his hand-drawn sketches for the cover’s design give space to all three. In contrast, the US cover by Karl Ferris uses a fisheye lens to imbue an otherworldly quality, with the trio looking as if they’ve been locked in a paperweight, and Hendrix was reputed to have been thrilled with Ferris’ results. The innovative infrared technique mirrors Hendrix’s inventive use of colour in his lyrics, and in the way he described the sounds he wanted to achieve when talking to Chandler and South African engineer Eddie Kramer. Moreover, the image emphasises Hendrix’s large, illustrious hands, foregrounding his expertise.

The UK and US versions of Are You Experienced not only have different covers, but different track listings. The UK version is going to be considered here, and the singles will be explored separately: tagging them on the end of the album weakens their power. ‘Purple Haze’ is a single in the ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ mould in being a complete statement, and feels unfairly anticlimactic after the album tracks. After all, ‘Purple Haze’ is the Experience’s fanfare.

‘Hey Joe’/‘Stone Free’

Personnel:

Jimi Hendrix: Guitar, vocals

Mitch Mitchell: Drums

Noel Redding: Bass

Recorded at De Lane Lea Studios, October–November 1966

Producer: Chas Chandler

Engineer: Dave Siddle

The Breakaways (Margaret Stredder, Gloria George, Barbara Moore): Backing vocals

Chart placings: UK: 6

‘Hey Joe’ (Billy Roberts)

The debut single of The Jimi Hendrix Experience is at once a curious and logical choice. Listening to cuts like ‘I’m A Man’ by Jimmy James and The Blue Flames (Hendrix’s previous band) proves there’s a sauntering assuredness that can also be found in ‘Hey Joe’. Hendrix’s half-spoken/half-sung vocal style must’ve made another blues standard seem like a natural choice to launch his next endeavour – especially in the UK, where the song had yet to garner the attention it had drawn in the US in various incarnations by different acts. Furthermore, Chas Chandler had hit the big time with The Animals’ reworking of the folk song ‘The House Of The Rising Sun’, and had shown the pop potential of brooding regret. Yet, ‘Hey Joe’ is a cod-blues folk song by Billy Roberts (Hendrix described it in the Are You Experienced notes as ‘a blues arrangement of a cowboy song’) that takes the form of a duologue between a cuckolded would-be murderer who’ll soon be on the run, and a supposed confidante, but the song just doesn’t quite make it in any of its many recordings. Hendrix excises the opening verses, straight into enquiring where Joe is going ‘with that gun in your hand’, and shows the join between the frenetic version by The Leaves and the lamenting sound of Tim Rose. Hendrix keeps the admonishing backing vocals of Rose – a rare incidence of female vocals on a Hendrix track, here supplied by The Breakaways (an earlier Hendrix cut features an unknown group) who can be heard on recordings by Petula Clark and Dusty Springfield – whilst realising that the propulsive walking bass of The Leaves is its most gripping ingredient. But this is the problem – listening to ‘Hey Joe’ is the aural equivalent of a patchwork quilt: the joins are evident. Some of Hendrix’s more committed live versions take this further by embroidering the song with licks borrowed from The Beatles: notably ‘Day Tripper’ and ‘I Feel Fine’.

The first take – available on the excellent The Jimi Hendrix Experience box set – touchingly reveals Hendrix being surprised at his own voice and asking for the backing track to be augmented to drown him out! Sometimes Hendrix would sing in darkness or facing away from others, such was his self-consciousness regarding his singing voice. Not only does this take show his lack of confidence in the recording studio, but it displays the incongruous backing vocals and is testament to the transformative effects of Hendrix’s guitar: this is threaded and weaved around a dated backing, but the track becomes three-dimensional. In short, without the virtuosity, it would be an almost tedious listen. An early live version in Paris is a misstep, showing Hendrix still working out the embellishments, and it’s an uncertain performance, with Mitchell’s drumming hesitant in its punctuation, and Hendrix not really inhabiting the swaggeringly defiant persona of Joe. Only Redding’s bass line is constant and assured. But, returning to the first studio version, Hendrix must’ve been inspired by the idea of ethereal backing vocals, as he’d reuse this to thrilling and unnerving effect on ‘Purple Haze’, and then to add a warmth to ‘The Burning Of The Midnight Lamp’.

Hendrix’s true debut/manifesto is to be found on the B-side ‘Stone Free’. Nevertheless, there’s an almost sepia quality to the instrumentation and vocals of ‘Hey Joe’ that is thrown into relief by the technicolor of the following singles, and the pensive solo still impresses every time. Also, Hendrix would begin tentatively to establish part of his signature sound, with the use of the ascending chromatic scale creating an exciting suspense. Really, this is the sound of Hendrix ‘looking through the bent-backed tulips’ before redesigning the landscape with ‘Purple Haze’.

The Experience performed ‘Hey Joe’ for the penultimate episode of Ready, Steady, Go! on 16 December 1966, alongside The Troggs, Keith Relf, Marc Bolan, and The Merseys. The close of Ready, Steady, Go! is often seen as symbolising the shift from pop to rock music, and indeed, Hendrix’s performance caused waves. Tony Crane – singer and lead guitarist with The Merseys – told Andy Neill for Ready, Steady, Go! The Weekend Starts Here: The Definitive Story of the Show That Changed Pop TV:

When we did RSG, we caught up with Noel (Redding had been on tour with The Merseys when he was in The Burnettes), who told us he was now playing bass with this new band. We said, ‘But you’re a lead guitarist – what are you doing playing bass?’ He said, ‘You haven’t seen this guy play. If you were in his band, you’d be playing bass as well!’ Noel introduced us to Jimi Hendrix, and he was the quietest guy you could ever meet. And then when he went on, playing his guitar with his teeth, our mouths were wide open!

Marc Bolan – whose comments are collected in the same publication – also found Hendrix’s performance remarkable:

Everyone else used to use backing tracks, but he was going to play live because they got him on the show the same day. I was in the control room with the producer, just sitting about, when they started ‘Hey Joe’, and this old lady really freaked out bad and said, ‘Turn the backing track down!’ Because it was really loud. All the machines were shaking. And they said, ‘But there is no backing track!’

Future glam rocker Bolan was performing the weirdly brilliant ‘Hippy Gumbo’. According to Carl Ewens’ Born to Boogie: The Songwriting of Marc Bolan, Hendrix was impressed, and predicted that Bolan would make it big. Whilst Bolan was no novice when it came to self-mythologising, ‘Hippy Gumbo’’s narrative about meeting an enigmatic stranger – ‘In the morning with the sun he pulled an automatic gun/He blew my soul, he blew my brain’ – would probably have appealed to Hendrix. Bolan had also briefly been a member of John’s Children, whose destructive stage act involved them flagellating each other with chains. And just like Hendrix did when supporting The Monkees, they would incur the fury of The Daughters of the American Revolution – not with their stage act, as Hendrix did, but by naming their debut album Orgasm.

Although Hendrix’s theatrics would go on to define his legacy, it’s clear here that what first astounded was his sound: and even on a track that was already becoming a bit of a cliché.

‘Stone Free’ (Jimi Hendrix)

The ersatz nature of ‘Hey Joe’ calls to mind the ‘Stone Free’ observation of those who ‘try to keep me in a plastic cage’. This B-side builds on the ‘I’m A Man’ proclamation ‘I’m a rolling stone!’ to assert Hendrix’s love of liberty. The chugging rhythm motors through and his vocal has a compelling impatience that combines to give the free stone a rollicking – rather than rolling – action. There’s also powerful use of one of Hendrix’s musical fingerprints – the expectant augmented-9th chord – and the relentless tolling of the cowbell looks ahead to the defiant piano of ‘Are You Experienced’: a metronome to keep the speaker on the run. Redding employing obstinati adds to a sense of paradox – dynamism and stasis: a texture that would recur in many of Hendrix’s recordings. But the track looks back as well as forward – the intro riff is a slower boogie, and if we sped this up, there would be the essence of Little Richard: Hendrix nodding at his legacy so far. Chandler claimed the song was recorded in little more than an hour, and there’s a palpable urgency in its mix. The producer was later to be frustrated by how long Hendrix would deliberate over his recordings, and it’s hard to deny that the painstaking workmanship paid off, but this recording is evidence of immediacy being just as powerful.

Most Hendrix writers feel duty-bound to bemoan the casual sexism of the lyrics, and then to extend this observation to Zeppelin, The Stones and the whole hypocrisy at the heart of the so-called swinging sixties. It’s certainly an observation that needs to be made, and a debate that must be developed. But whilst rock, blues, pop etc. are not exactly crucibles of gender equality (and let’s not forget that men are derided as little red roosters, hound dogs, or celebrated for their big ideas and little behinds too), often the constraints of relationships are a protean – if unoriginal – metaphor for social constraints in general in pop music, and for eschewing a society that ties us to parents, teachers, presidents and employers, possibly even more than to partners. Hendrix himself was certainly oppressed by the political system he was born into, but also seems to have been inhibited more by paternal control, the force of the military or the rules of his bandleaders than by his relationships with women at this point in his life. Romantic relationships appeared to mature into metaphors for segregation later in Hendrix’s work too. In fact, he was to live for only two more years after the Supreme Court declared segregation to be unconstitutional. In this context, it’s more difficult to view ‘Stone Free’ as simply a complaint about ‘woman here, woman there’. Politically speaking, the implications of being black and itinerant go much deeper, as black people were more likely to be arrested for vagrancy. Being stone free is a radical act in this context.

More personally, Al Hendrix said he was imprisoned in an army stockade the night Hendrix was born, as the officers feared that a new father would go AWOL to visit the child: Hendrix junior seemed to be in the shadow of that stockade for much of his life. In some ways, the words simply propel the music all the way to racing fade-out, a sound that would be echoed by Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side Of The Moon and Giorgio Moroder’s disco recordings. There is a good argument for Hendrix’s lyrics being almost dispensable on a number of tracks, or at least seen more as a selection of complementary sounds. After all, how could the words consistently compete with the playing? The free vowels of ‘stone free – ee!’ echo the scream of the guitar rather than the other way around. That is, the words reply to the sounds, not vice versa, which moves on from the call-and-response playing of the early blues. Hendrix later lamented to his PR man Keith Altham: ‘The words are so bland that nobody can get into them.’ Whilst this isn’t always the case, the lyrics are mostly subservient to the sound.

A more valid objection than one based on the politics of relationships is that Hendrix would recycle this metaphor and produce paler and paler versions of it throughout his career, starting with the ‘Purple Haze’ UK B-side ‘51st Anniversary’. Indeed, Hendrix was thinking of releasing ‘Stone Free’ as a single in its own right in 1969, almost as a reset action. The track was re-recorded in New York with The Experience and Family’s Roger Chapman, with Amen Corner’s Andy Fairweather Low providing fervent backing vocals. The take is poised; swaggers more than sprints but, unsurprisingly, lacks the spontaneity of the original. The re-recording is available on the The Jimi Hendrix Experience box set and the Valleys Of Neptune compilation. (See entry under Valleys Of Neptune also.)

‘Purple Haze’ (Jimi Hendrix)

Personnel:

Jimi Hendrix: Guitar, vocals

Mitch Mitchell: Drums

Noel Redding: Bass, backing vocals

Recorded at De Lane Lea Studios and Olympic Studios, January–February 1967

Producer: Chas Chandler

Engineers: Dave Siddle, Eddie Kramer

Chart placings: UK: 3, US: 65

Whether ‘Purple Haze’ is a paean to epiphany or a keening on bewilderment lyrically, musically it’s indubitably eye-and-ear-opening. And here’s the Hendrix chord: E7#9. The Beatles and Cream had already utilised variations on this chord in rock, whilst jazz musicians John Coltrane and Wes Montgomery had included it in their work. However, its quirkiness vanishes under Hendrix’s rule, becoming at once subversive, exciting and disquieting: it’s a feral blast. Moreover, it’s married to the tritones that announce the song, and these were known as ‘the Devil in music’, resulting in the church banning the interval’s threat of dissonance in the Middle Ages. The intro implies a conversation already begun, and challenging and uneasy conversations yet to come: an uncanny sound to fill the airwaves of the Summer of Love. Yet, for Hendrix, the unresolved and homeless nature of the tritone is the perfect metaphor for his peripatetic spirit. Miles Davis’ version of the Richard E. Carpenter composition ‘Walkin’’ (supposed: the track’s pedigree is as complex as ‘Hey Joe’s!) employs tritones in the intro to arresting effect too, and Hendrix is thought to have admired the piece. Keith Shadwick also notes that the Hendrix chord can be heard in Henry Mancini’s ‘Peter Gunn’ theme, which similarly makes evocative use of obstinati. This was one of the earliest pieces that Hendrix learnt to play, and he would often segue into it when a take of one of his own compositions faltered. Indeed, ‘Purple Haze’ is said to have been written after Chandler overheard Hendrix experimenting with a riff in the dressing room of the Upper Cut, and urged him to form it into a song. However, its lyrical inspiration is quite different – Hendrix is said to have been influenced by dreaming of being under water: a trope that would recur in ‘1983… (A Merman I Should Turn to Be)’. (Hendrix also said he’d been inspired by a dream to write another song at about the same time: the mysterious ‘First Look Around The Corner’.) The sensation of everything slowing as one pushes against the current is evident in his cover of Bob Dylan’s ‘All Along The Watchtower’ too, and didn’t just inform his lyrics but his musical lexicon. Hendrix began to work out a template whereby the chord sequences might be quite simple, but the augmentation of these would be innovative and elaborate.

On ‘Purple Haze’, he’s fretting the chords differently so that unusual voicings or patterns can be played around them, heightening the track’s uncanny feel. (Hendrix essentially begins the song in a medieval style before launching into psychedelic blues rock, mirroring his updating of the blues itself. But for Hendrix, updating meant trailing the roots behind him.)

This feeling of disorientation is further enhanced by Hendrix’s pioneering use of the Octavia effect pedal, designed by electrical engineer Roger Mayer whom Hendrix first met at London’s Bag O’ Nails club, and who would eventually accompany him on tour. More accurately speaking, it wasn’t quite the Octavia that Hendrix would use later, but an earlier version known as Evo1 that worked along similar lines. Hendrix explained the device to Music Maker: ‘It comes through a whole octave higher so that high notes sound like a whistle or flute.’ This is a redolent description but is also revealing of how Hendrix often strove to recreate sustained sounds like brass or woodwind instruments, with him frequently being compared to saxophonist John Coltrane in his vision and invention. This disconcerting sound is apparent in Hendrix’s original lyric where he positions himself ‘Down on the ceiling looking up at the bed’: an Escher queasiness that the Octavia continued in its almost 3D sound. Interestingly, the lyric evolved from an initial exploring of obscurity (the original first line being ‘Purple Haze, Jesus saves’) to one of emerging revelation and wonder. This aura of awe is enhanced in the solo, where the notes spark and spiral off from the melody as if from a Catherine wheel, and the backing vocals go into slow motion, reminding us of that underwater drag. Hendrix had been experimenting with different effects whilst still a backing musician, and is said to have been intrigued by Elmore James’ innovations with electric pickups on acoustic guitars, and ‘Purple Haze’ was finally the perfect vehicle.