9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Sonicbond Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

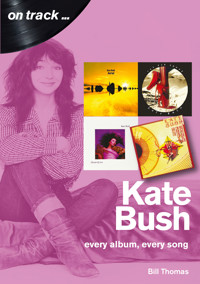

Kate Bush started her career at the top, the spellbinding ‘Wuthering Heights’ giving her a number one hit single with her first release. Yet from there, artistically at least, the only way has been up. For while the sales of both singles and albums over the five decades since have had their peaks and troughs, every new release has seen Bush refuse to be boxed in by past success but instead continue to take the musical chances that have characterised her career from day one.

Across ten studio albums, including director’s cut reassessments of two of them, and a live record of the 2014 Hammersmith Apollo residency, Kate Bush has constantly sought new ground, reinventing her sound time and again. She has often strayed from the commercial path of least resistance to examine the less travelled musical byways that have provided the inspiration for an extraordinary body of work - quite unlike anyone else’s.

With a string of platinum albums and hit singles to her credit, Kate’s is a fascinating journey. This book examines her entire recorded catalogue from The Kick Inside through to Before The Dawn, hoovering up all the B-sides and the rarities along the way. It’s a comprehensive guide to the extraordinary music of Kate Bush.

Bill Thomas was born in the mid-1960s, and after leaving the bright lights and romance of management accountancy behind him, he has carried on what he optimistically calls ‘a career’ in both music and football over the course of the last 30 years. Since he couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket and has concrete feet, that career has been limited to nothing more than writing about both disciplines, which is about as close as he is ever going get. He lives in Shropshire, UK.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 283

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Sonicbond Publishing Limited

www.sonicbondpublishing.co.uk

Email: [email protected]

First Published in the United Kingdom2021

First Published in the United States 2021

This digital edition 2022

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data:

A Catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Copyright Bill Thomas 2020

ISBN 978-1-78952-097-2

The right of Bill Thomas to be identified

as the author of this work has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Sonicbond Publishing Limited

Typeset in ITC Garamond & ITC Avant Garde

Printed and bound in England

Graphic design and typesetting: Full Moon Media

Acknowledgements

Several months of reading and listening to anything and everything I could find on Kate Bush, as well as immersing myself in the albums once again have ended up as this book.

The sources of the quotes have been noted through the text, so grateful thanks go in particular to the music press of Olde England from 1978 onwards. We are going to miss it when it’s gone and that day is coming closer all the time. The internet simply isn’t a substitute for it.

That said, the internet is handy for searching for things lost and seemingly impossible to find. On that front, I must recommend Kate’s official site – katebush.com – for the surprisingly thorough discography, unusual among such sites. The Kate Bush Encyclopedia – katebushencyclopedia.com – is a fountain of knowledge on anything and everything connected with Kate while Gaffaweb – gaffa.org – is simply full of links and articles if you want to go down the rabbit hole. My thanks to them all.

Contents

Introduction

The Kick Inside (1978)

Lionheart (1978)

On Stage EP

Never For Ever (1980)

The Dreaming (1982)

Hounds Of Love (1985)

The Sensual World (1989)

The Red Shoes (1993)

Aerial (1995)

Director’s Cut (2011)

50 Words For Snow (2011)

Live Albums

Live At Hammersmith Odeon

Before The Dawn

Compilations

The Single File 1978-1983

The Whole Story

This Woman’s Work: Anthology 1978-1990

Remastered

The Other Sides

Other Collaborations

Introduction

Kate Bush’s career, now into its fifth decade, has been longer, more complex and, increasingly, infinitely stranger than ever we could have expected – even on that first encounter with ‘Wuthering Heights’, a single that sounded like nothing else on earth as it nestled down for four weeks at number one on 5 March 1978, displacing Abba at the top.

More than 40 years distant, it’s hard to comprehend just how weird that song sounded on release; that keening, operatic vocal cutting through radio stations then in thrall to the sound of disco and the early stirrings of punk and new wave. Amid music that was getting faster and faster, even before bpm became a thing, ‘Wuthering Heights’ was a regal, stately piece, the child of progressive rock and Pink Floyd in particular, unsurprisingly given the patronage bestowed upon Bush by David Gilmour. That it climaxed with Ian Bairnson’s guitar solo, straight out of the Gilmour playbook, was no coincidence.

The song on its own was striking enough. But when it was wedded to the photographs of the devastatingly beautiful waif, and that video, all young Miss Haversham – yes, I know, different book – cavorting acrobatically across the screen, you had the whole package. ‘Wuthering Heights’ was unstoppable, as four weeks at number one underlined.

But where to go from there? Was she just a one-hit wonder, a novelty act? Her overtly theatrical performance had echoes of ‘Love You Til Tuesday’ era David Bowie, another songwriter who had fallen under the visual spell of Lindsay Kemp a decade before, but Bowie changed dramatically prior to achieving consistent hits. With Bush too, as time went by, those slightly twee early presentations gave away to something altogether darker and more engaging, things which have certainly aged better – but as far as the music went, the mature artist was already there, right from the outset. Any writer, any singer would, to this day, kill for a song as fully formed as ‘The Man With The Child In His Eyes’, something she pieced together as a thirteen-year-old.

That song, and plenty of others on her debut album, hinted that this was an artist for the ages, despite the marketing strategy of the time that was more appropriate for a swift cash-in rather than the long run. A second album and a concert tour followed within a year, but from there, there was a retreat from the public eye. That was a reaction to the amount of work that went into mounting the kind of theatrical production she was looking to front and to the length of time it took her away from writing and recording, very clearly her central focus.

The burgeoning video format was an area that increasingly engaged her too, enabling her to promote the songs visually without the limitations she faced in trying to do so in concert. And, let’s be honest, the camera loved her in return.

That innocent teenage beauty was not the whole story, for this was no ingenue. From the outset, Kate Bush knew her own mind and, backed by that early success, she was ruthlessly determined to exercise it as she saw fit. Her record company, EMI, were taken aback by the increasingly idiosyncratic waters into which she sailed with Never For Ever and especially The Dreaming, a record exec’s nightmare sculpted in vinyl. Time has shown them to be even better records than they seemed at the time; what looked like self-indulgence is now shown to be her grasping for something richer and deeper, a quest that finally found its form in 1985’s Hounds Of Love, a rarity of its time in that it still sounds as good today where so many of its contemporaries were destroyed by jarring production techniques that have not endured.

Hounds Of Love was ambitious yet accessible, imperious yet commercial, the landmark recording that ensured that Kate Bush’s artistic vision could never again be questioned. From there, she was unequivocally in charge and she was going to make full use of that freedom. Who else would call in a trio of matronly Bulgarian ladies to sing on the follow up to a smash hit album? Or base its lead single around the legendarily opaque prose of James Joyce?

A turn back towards normality – whatever that is – then characterised The Red Shoes, a record that swooped and sparkled but which also sounded a little bit weary of the whole process of making and, more especially, promoting records, something she largely avoided on its release. A hiatus seemed inevitable, but the eventual twelve years was a little excessive. Few artists could survive such a gap between albums with their fanbase intact and Bush herself voiced concerns as to whether anybody would still want to listen to anything she had to say. An album with songs about washing machines, the incantation of pi to 137 decimal places and which culminates in a forty-two-minute song suite doesn’t immediately sound the most commercial of ideas, but Aerial was a late-career triumph, up there with Hounds Of Love.

Silence reigned once more until there was a burst of activity around the founding of her Fish People label. 2011’s Director’s Cut was quintessential Kate Bush, the auteur whose vision of flawlessness is always elusive, the perfectionist in thrall to the power of mistakes who still wanted another crack at getting it right. Remarkably, inside five months of that release, there was a new album of brand new material too, 50 Words For Snow. And then the world went into meltdown as she announced a return to live performance in 2014 with a month-long residency at London’s Hammersmith Apollo, the Odeon as was, the setting for her famous 1979 live video.

Before the Dawn was as breathtaking as everyone hoped, its commemoration in the live album of 2016 the most recent material from her, save the flurry of remasterings and reissues that have followed.

Will there ever be another live show? Will there be more new albums? Much of her longevity has come from her ability to maintain that sense of mystique and mystery, so the likelihood is that, once again, we’ll only know when she wants us to know and when the recordings are ready to drop. It’s a nicely ascetic approach in an increasingly infobese world…

Note: all songs composed by Kate Bush unless otherwise noted

The Kick Inside (1978)

Recorded at AIR Studios, London, June 1975 – July 1977Producer: Andrew PowellExecutive producer: David Gilmour (‘The Saxophone Song’ and ‘The Man With The Child In His Eyes’)Musicians: Kate Bush: lead and backing vocals, pianoAndrew Powell: piano, bass, Fender Rhodes, celeste, synthesizer, beer bottlesDuncan Mackay: piano, Fender Rhodes, Hammond organ, clavinet, synthesizerIan Bairnson: guitars, backing vocals, beer bottlesDavid Paton: bass, background vocals, acoustic guitarStuart Elliott: drums, percussionAlan Skidmore: tenor saxophonePaul Keogh: guitarsAlan Parker: acoustic guitarBruce Lynch: bass guitarBarry de Souza: drumsMorris Pert: percussion, boobamPaddy Bush: mandolin, backing vocals Arrangements by Andrew PowellOrchestral conductor: David KatzReleased: 16 February 1978Label: EMIHighest chart placings: UK: 3; Netherlands: 1; Portugal: 1; Belgium: 2; Finland: 2; New Zealand: 2; Australia: 3; France: 3. The Kick Inside was certified a platinum disc in the UK, Australia, Canada, the Netherlands and New Zealand. Running time: 43:13

When The Kick Inside was released on 16 February 1978, Kate Bush’s debut single ‘Wuthering Heights’ had had just a couple of weeks in the charts and was up to number 27 – it took a little longer to break a new artist back then. It would take that cinematic single another fortnight to reach number one, dragging its accompanying album along in its wake to a peak position at number three, remarkable fare for a teenage debutant.

By then, the legends and mythology that went on to surround Kate Bush had already begun being constructed, the young girl prodigy who, via a friend of a friend – Ricky Hopper, part of Pink Floyd manager Steve O’Rourke’s organisation – came into contact with David Gilmour just as The Dark Side Of The Moon was about to catapult him into the Lear jet owning rock aristocracy and, from there, came to the attention of EMI.

All of which, except maybe the Lear jet, was true, Gilmour entering the picture in 1973, listening to the fourteen-year-old’s fairly rudimentary recordings before making a fresh set with her in the summer of that year. Bush herself admitted that was the age ‘when I started taking it seriously’; Gilmour seeing enough in that early material to arrange and finance a full-scale session at AIR Studios in June 1975, just as Floyd were finishing off Wish You Were Here at Abbey Road. The session, which yielded ‘The Saxophone Song’, ‘Maybe’ and the outstanding ‘The Man With The Child In His Eyes’, caught the attention of EMI and, by July 1976, she was signed on what was effectively a development deal to keep her under wraps and under contract.

Record companies often get a bad rap, but that decision was shrewdness itself, allowing her to work further on her songs, begin to play live on the pub circuit with the KT Bush Band, make more demos, and study dance and mime under Lindsay Kemp among others – something that was to prove crucial in the burgeoning video age that lay ahead.

As with any teenager, being told to ‘hurry up and wait’ made life pretty frustrating for Bush. However, in keeping their powder dry, not merely allowing her to stockpile more songs that were strong enough but to mature as a person too, the EMI stance was eminently sensible. Given the quality of the material and the way that she looked, once revealed to the world, she was always likely to be caught up in a publicity maelstrom that would require a steely constitution, mental and physical, to withstand it. That she was steelier than they imagined was brought home to them when she went into battle with them – and won – over the first single. EMI wanted ‘James And The Cold Gun’. Kate Bush wanted ‘Wuthering Heights’. History suggests she was right.

She had already demonstrated her single-minded vision as the album was being made, quoted in Sounds as saying, ‘I was lucky to be able to express myself as much as I did, especially with this being a debut album. I basically chose which tracks went on, put harmonies where I wanted them. I was there throughout the entire mix. Ideally, I would like to learn enough of the technical side of things to be able to produce my own stuff.’

Even then, not all was plain sailing, for EMI were determined that she was going to be launched at precisely the right moment, indicative of their belief that here might be an artist who could follow in the highly successful footsteps of The Beatles, Pink Floyd and Queen. Having initially slated ‘Wuthering Heights’ for an autumn 1977 release with the album to follow quickly on its heels, it was pushed back further to the point where the single was only finally ready to go in December that year. Early promo copies did reach a few radio stations, but the single was pulled at the last moment so as not to get lost in the Christmas rush, wise counsel as it proved; otherwise, it might have been mown down by EMI’s huge chart-topper that year, Wings’ ‘Mull Of Kintyre’.

Instead, 1978 was going to be the year in which she was unveiled. More than that, 1978 was going to be her year. Two UK hit singles including a number one, a further number one with ‘Moving’ in Japan, a number one album in Portugal and the Netherlands, the ninth biggest selling album of the year in the UK, eventual platinum status for The Kick Inside in five countries, those are just some of the extraordinary achievements clocked up by a truly striking record.

As you might expect from a first album by a performer who was so young then and who has gone on to have such a lengthy career thereafter, The Kick Inside seems a lifetime away from the performer who owned the Hammersmith Apollo when she performed her Before The Dawn concerts 36 years later. None of those songs were chosen for that performance, perhaps because age and the changes it brings to the voice made such vocal gymnastics all too demanding across so many shows, or perhaps because, like many of us who are rough contemporaries of hers, coming across a snapshot from our teenage years can be embarrassing, especially if it’s put in front of the world rather than our immediate circle.

While that’s understandable, there’s nothing much on The Kick Inside to be embarrassed about, for many of the foundation stones of her career were already in place. Great songwriting, intelligent lyrics, innovative ideas and, as much as anything, her attitude, her refusal to be manipulated or to do anything that she wasn’t happy with. The phrase diva is now used largely as a pejorative, tacked on to a description of self-entitled boorishness. But to use it in its proper sense, a female singer of exceptional talent, a self-contained artist able to set her own rules, The Kick Inside serves supremely well as the first flowering of one of the great divas.

For not only did she know what she wanted, she knew what the public wanted, as she revealed in a ‘Self Portrait’ promo LP distributed among radio stations on the album’s release.

There are thirteen tracks on the album and one of the most important things was that, because there were so many, we wanted to try and get as much variation as we could. To a certain extent, the actual songs allowed this because of the tempo changes, but there were certain songs that had to have a very funky rhythm and there were others that had to be very subtle. I was really helped by Andrew Powell, who is quite incredible at tuning into my songs. You can so often get a beautiful song, but the arrangement can completely spoil it – they have to work together.

‘Moving’ 3:01

While in the UK it was ‘Wuthering Heights’ that blazed the trail, in Japan, ‘Moving’ is the song that they first took to their hearts, reaching number one in their singles chart.

On the album, it’s a very unusual opener given it starts with whale song, taken from Songs From the Humpback Whale, pieced together by Roger Payne – a record which itself sold over 100,000 copies and played a big part in the ‘save the whales’ campaign of the 1970s. That was a deeply conceptual move, Bush explaining later in Sounds that, ‘Whales say everything about moving. It’s huge and beautiful, intelligent, soft inside a tough body. It weighs a ton and yet it’s so light it floats. The whales are pure movement and pure sound, calling for something, so lonely and sad...’

It may well have opened the record because it was perhaps the closest song in sound and spirit to ‘Wuthering Heights’. It gave a recognisable entry point to those who had already heard the single, the chief market for the album in its early weeks, easing them into the album. The song is a tribute to Lindsay Kemp, Bush saying:

He needed a song written to him. He opened up my eyes to the meanings of movement. He makes you feel so good. If you’ve got two left feet it’s, “You dance like an angel darling.” He fills people up, you’re an empty glass and glug, glug, glug, he’s filled you with champagne. He taught me to express things with your body and that when your body is awake, so is your mind. He would put you into emotional situations, he’d say, ‘Right, you’re all now going to become sailors drowning and there are waves curling up around you!’ Everyone would just start screaming!

‘The Saxophone Song’ 3:51

Next up is a much more conventional piece, certainly initially, something of a torch song, albeit aimed at the instrument rather than the instrumentalist, indicative of the different angles at which Bush would come at subjects.

The recording dates back to the June 1975 Gilmour demos, which perhaps explains the Floydian keyboard lines that end the song, but naturally, it’s the tenor sax part on which the song hinges. It’s played by Alan Skidmore, already then a veteran of the British jazz and blues scene, a devotee of John Coltrane who had previously recorded with Alexis Korner, John Mayall, Sonny Boy Williamson, The Nice and Soft Machine among many others.

Bush’s lyric of being besotted by the sound of the sax – including a rare rhyming couplet that shackles bowels and vowels together – rises on Skidmore’s sax part and it’s testimony to all involved that rather than it being some sugary, lachrymose confection, Skidmore is allowed to give his jazzier impulses free rein, the recording all the better for that less melodic element.

‘Strange Phenomena’ 2:57

The 1970s were a time when ‘alternative’ ideas, ways of life and of thinking that had been the preserve of the hippies and their culture in the ‘60s, were coming into the mainstream. That took many forms, largely under the heading of ‘mysticism’, but that could encompass a spectrum of things from the crowd-pleasing spoon bender Uri Geller at one end, through Tarot cards and the use of the Ouija board and on to the rigorous philosophical ideas propounded by Gurdjieff at the other. Mind-expanding times but now, largely, without the use of mind-expanding substances.

‘Strange Phenomena’ picks up on that – as does ‘Them Heavy People’ later – focusing in particular on synchronicity, as Bush explained at the time. ‘It’s all about the coincidences that happen to all of us all of the time. Like maybe you’re listening to the radio and a certain thing will come up, you go outside and it will happen again. It’s just how similar things seem to attract together, like the saying “birds of a feather flock together.” It’s just strange coincidences that we are only aware of occasionally. It happens all the time.’

It’s a subject that she was clearly invested in, ahead of what would become the New Age curve in the mid-1980s. It’s intriguing, then, that she undercut the serious nature of the subject matter in live performance, singing the song in the persona of a stage magician, that bastion of sleight of hand, deception and trickery.

The song got a belated single release, albeit only in Brazil, in June 1979, when it was paired with ‘Wow’ from Lionheart as its B-side.

‘Kite’ 2:56

The b-side to ‘Wuthering Heights’, this is cod-reggae of a sort that The Police were simultaneously specialising in. It is believed that the poetry police still have a warrant out for her arrest for rhyming ‘belly-o’ and ‘wellio-s’. The things we think we can get away with in our youth…

The lolloping groove is enough to excuse a multitude of sins such as that, infectious and uplifting in equal measure, a feelgood performance timed to perfection to lighten the mood after a pretty heavy opening trio of songs on the album. Whether that was down to Bush or producer Andrew Powell is lost in time, but it was a shrewd decision, underlining the importance of using the different dynamic range of each song so that they complement rather than fight with each other.

Lyrically it’s a little darker than the music, an allegory perhaps of Bush’s vision of the future she’s about to embark upon, a realisation that if The Kick Inside is a success, life won’t ever be the same again. The song’s heroine starts out tired of a mundane life, rooted to the ground, dreaming of the freedom to soar above it all like a kite. But once that freedom, or success, comes along, there’s a sudden desire to go back to those roots and all the old certainties once more. Perhaps this song was an early, subconscious note to self that the trappings of celebrity would prove to be a very short-lived thrill?

‘The Man With The Child In His Eyes’ 2:39

Recorded in that Gilmour session at AIR Studios in June 1975, this is the most jaw-dropping song on the album; extraordinary in composition, form and execution, the more so when you recall she wrote it at thirteen and recorded it at sixteen. A quite traditional recording – voice, piano, orchestral backing – it was so good that it was easy to imagine it having come from the pen of a long-established master of the craft like Paul McCartney. This song more than anything else opened the world’s eyes to just how talented Kate Bush was and just what potential there was still to be tapped. That it won the Ivor Novello Award for ‘Outstanding British Lyric’ in 1979 merely underlined its mature brilliance. It reached number six on its release as the album’s second single on 26 May 1978 – number three in Ireland – the mix marginally different in that it added the echoing ‘He’s here’ phrase at the start.

That success was crucial in her future career because for those who hadn’t invested in the album, it immediately proved not only that she was no one-hit-wonder but nor was she the slightly unhinged character that the ‘Wuthering Heights’ video suggested.

Bush herself realised that the stakes were high on its release: ‘I so want ‘The Man With The Child In His Eyes’ to do well. I’d like people to listen to it as a songwriting song as opposed to something weird, which was the reaction to ‘Wuthering Heights’. If the next single had been similar to that, straight away I would have been labelled and that’s something I really don’t want. As soon as you’ve got a label, you can’t do anything. I prefer to take a risk. That’s why this song is so important’.

It was very much a songwriter’s song as she explained further. ‘I feel as though I’ve built up a real relationship with the piano. It’s almost like a person. If I haven’t got a particular idea, I just sit down and play chords and they almost dictate what the song should be about. The inspiration for this song was just a particular thing that happened when I went to the piano. The piano just started speaking to me.

‘It was a theory that I had had for a while that I just observed in most of the men that I know, the fact they are still just little boys inside and how wonderful it is they manage to retain this magic. I’m attracted to older men I guess, but I think that’s the same with every female. I think it’s a very natural, basic instinct that you continually look for your father … you look for that security that the opposite sex in your parenthood gave you as a child.’

‘Wuthering Heights’ 4:28

Closing side one on the original album, ‘Wuthering Heights’ contributed to a strangely sequenced album, one that looks odder still in the days of CD with this and ‘The Man With The Child In His Eyes’ marooned in the middle. Record sequencing lore of the time said that artists should place their three best tracks thus: one at the start of each side and the other at the end of side one in order to persuade radio DJs, inundated with dozens of new albums to plough through each week, to turn the record over and try side two. That is surely the only explanation for this sequence, for if ‘Moving’ and ‘The Kick Inside’ were obvious conceptual bookends to the recording, where else could ‘Wuthering Heights’ go? It’s hard to imagine any song following immediately after it so that brief pause as you turned the vinyl or the cassette over made perfect sense.

Self-evidently, the song was inspired by Emily Brontë’s book, Bush saying on the BBC children’s TV show Ask Aspel:

I saw a series on the television years ago, it was on very late at night and I caught literally the last five minutes of it where she was at the window, trying to get in. It just really struck me, it was so strong. I read the book later, before I wrote the song, because I needed to get the mood properly.

Adding further to the tale in other interviews, she explained:

Cathy has actually died and is coming back as a spirit to come and get Heathcliff again. It shows a lot about human beings and how if they can’t get what they want, they will go to such extremes in order to do it. She wouldn’t be alone even when she was dead. She had to come back and get him … When I was a child, I was always called Cathy and I just found myself able to relate to her as a character. It’s so important to put yourself in the role. When I sing that song, I am Cathy.

‘Wuthering Heights’ is perhaps not quite as strange a song as it seems, particularly given the twists and turns on so much of the other material on the album. Strong melodically and ending with a fine Gilmouresque guitar solo from Ian Bairnson, it’s the piercing vocal that makes it unique, Bush herself well aware of the extreme nature of the performance: ‘It was really specifically for that song that it was that high. Because of the subject matter and the fact that I’m playing Cathy, and that she was a spirit and it needed some kind of ethereal effect, it seemed to be the best way to do it, to get a high register.’

As well as the UK, it reached number one in Ireland, Australia and New Zealand and went top ten in the Netherlands, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Belgium, Norway and Switzerland. It was later re-recorded with a new, more restrained vocal performance for the B-side of the ‘Experiment IV’ single and The Whole Story hits album in 1986.

‘James And The Cold Gun’ 3:34

This was EMI’s original preference for the lead single and it isn’t hard to see their point. It would have slotted into the new wave mood that was sweeping the charts at the time and would have been an easier sell as a consequence. It was the safe option, but as a consequence, it would have been far more restricting than ‘Wuthering Heights’. For if that song led to initial caricatures from the likes of impressionist Faith Brown on TV, at least it was a distinct image and one she knew she had the material to undercut later. ‘James And The Cold Gun’ would, instead, have seen Kate Bush set up as another ‘rock chick’ and slipping away from that obvious stereotype would have been altogether more difficult for her to do.

It feels like one of those songs that was bolted on to offer the variation she yearned for across the thirteen tracks, yet it was one of the glut of songs she’d written well in advance. It was played on the pub circuit by the KT Bush Band as she was preparing to make the album and it does have all the hallmarks of a powerful live song – it wasn’t surprising to find it playing a key role on the Tour Of Life in 1979.

It’s more obvious musically than some of the others, more direct and in your face, in the way that ‘Don’t Push Your Foot on The Heartbrake’ would be on Lionheart, her second album. The bluesy instrumental section that was cut short at the end was clearly intended for extended play in concert, bounty hunter Bush bringing the song to life and gunning down all comers, including her audience. Both tracks were obvious ones for inclusion on the On Stage EP that followed in the wake of her live shows in August 1979.

‘Feel It’ 3:02

It’s an obvious comparison to make, but ‘Feel It’ opens very much like a Carole King song, a piece that could sit very easily alongside anything on Tapestry. That’s ironic given that Bush had been vocal about her attitude to singers like King who she politely dismissed as being too retiring in their performance, saying that men brought a far more positive edge to things and that she wanted to bring more of that to her record, pointing to the way Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen would attack their songs. ‘It really puts you against the wall, and that’s what I’d like my songs to do’.

That would have been entirely the wrong treatment for a song about exploration, naivety, uncertainty and even back then, she had the wit to realise that a rather more winsome delivery better suited the subject. While other songs are more oblique in their meaning, ‘Feel It’ is pretty upfront – ‘My stockings fall onto the floor, desperate for more’ is as obvious as it gets. The strength of the song lies in the way the helpless romantic rubs up against the realist – ‘It could be love or it could just be lust’. If you ever wanted an explanation of the chasm between adolescence and adulthood, written by someone on that cusp, this is it.

‘Oh To Be in Love’ 3:18

Two years old by the time of its release, ‘Oh To Be In Love’ was originally written and demoed in the summer of 1976, just as she signed her first contract with EMI. On the face of it, it’s a more simplistic view of love and romance than ‘Feel It’, this one giving in to the rapture of the romantic rush, but there’s something arch about the line, ‘Slipping into tomorrow too quick’, the whole song having that nagging sense that if something feels too good to be true, it probably is.

It’s a song that we’ve come to see as having some of those quintessential Kate Bush elements, songs holding several, often contrasting and contradictory ideas inside them at once. That rapturous and yet slightly jaundiced view of romance is one example, but there’s also the opening verse full of wonder at just how big a role pure chance plays in two people meeting and connecting. And yet having already heard ‘Strange Phenomena’ on the way to this track, in the back of the mind is that thought, ‘Just how random is random anyway?’

Musically, its most striking feature is the use of male backing vocals in the chorus. They’re a little bit hammy on the face of it, but they have the effect of illuminating Bush’s voice and the almost operatic range that she controls so well. It was clearly a technique she liked for it was a go-to idea on a number of songs, certainly on her first four albums.

‘L’Amour Looks Something Like You’ 2:27

‘L’Amour Looks Something Like You’ concludes something of a trilogy, swimming in the same waters as ‘Feel It’ and ‘Oh To Be In Love’ but with another subtle shift. This one is looking back at an affair, perhaps no more than a one night stand, replayed with affection, disappointment and undeniable longing. ‘That feeling of sticky love inside’ certainly takes us a couple of steps along the road from the falling stockings of ‘Feel It’.

It’s an awkward, slightly gauche song, but paradoxically that’s where its strengths lie. If ‘The Man With The Child In His Eyes’ was the work of a child prodigy, ‘L’Amour Looks Something Like You’ is a reminder that the album was actually the work of a teenager, with all the hormonal self-consciousness which that implies. Remember too that this was an era where youthful sexuality, especially female sexuality, was less often expressed and it’s easy to picture her fumbling her way towards a new vocabulary, bringing to light emotions and ideas that women of the time were encouraged to keep to themselves.

The song is full of those vocal swoops that had already become a Kate Bush trademark, but it’s a slightly pedestrian production that never quite catches fire. The lyric may be reflective, a rueful look back at what might have been, but musically it never quite takes flight the way that other songs on the record do.

‘Them Heavy People’ 3:04

A beguilingly eccentric production, it’s a reminder of a different age that ‘Them Heavy People’ was not released as a single in the UK because, such was the pace things moved at in 1978, two singles were considered enough from one album – a third would only get in the way of the upcoming second album. That it would have been a hit was emphasised by its success in Japan where it was the follow up to ‘Moving’ and reached number three. It finally got its moment in the sun in the UK as the lead track on the On Stage live EP in August 1979.