Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

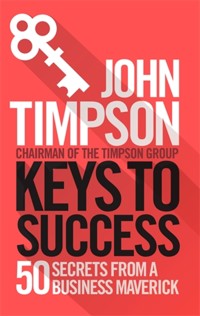

John Timpson, Chairman of the eponymous British high street chain, knows a thing or two about running a successful business. Over many years he revolutionised how his firm worked, developing his philosophy of upside-down management, and has reaped the rewards – the Timpson group (which includes the Snappy Snaps and Max Spielmann chains). Timpson, whose weekly Daily Telegraph column and regular media appearances have made him a well-known business commentator, here shares his secrets. Full of actionable advice, Timpson's Top Business Tips is a step-by- step MBA for business women and men who need results now. From encouraging flexible working, having a happy index and a great bonus scheme to the importance of checking the cash on hand every day and planning for disaster scenarios; from why you should never make decisions at meetings to the value of a mentor – even when you're at the top – these are essential markers on your roadmap to business success, whatever business you're in.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 290

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

KEYS TO

SUCCESS

KEYS TO

SUCCESS

50SECRETS FROM A BUSINESS MAVERICK

JOHN TIMPSON

Published in the UK in 2017

by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Grantham Book Services,

Trent Road, Grantham NG31 7XQ

Distributed in the USA

by Publishers Group West,

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa

by Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in Canada

by Publishers Group Canada,

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300

Toronto, Ontario M6J 2S1

ISBN: 978-178578-199-5

Text copyright © 2017 John Timpson

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in Agmena Pro by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

This book is dedicated to all the Timpson colleagues who make things happen. Twenty years ago we started to run the business by giving every colleague the authority to do their job in the way they know best. They have repaid that trust by creating a great business. I am proud to have played a small part in that success.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Timpson CBE was born in 1943 and educated at Oundle and Nottingham University. In 1975 he became Managing Director of William Timpson Ltd, the business that had borne his family name since 1865, and he is now sole owner of the company, which has a turnover in the UK of £200m per year. His previous books include Ask John (Icon, 2014), based on his Daily Telegraph column of the same name, and High Street Heroes (Icon, 2015). His book Upside Down Management (Wiley, 2010) was described by the Financial Times as ‘a practical and inspirational manual for anyone who runs a business’. Timpson and his late wife Alex were foster carers for 31 years, during which time they fostered 90 children. He lives in Cheshire.

Contents

Introduction

1Break the rules

2Upside Down Management

3Trust your people

4Only two rules

5No one issues orders

6Pick people with personality

7Encourage flexible working

8Say goodbye to drongos

9Promote from within

10Be wary of outsiders

11Look after the superstars

12Rescue over-promoted colleagues

13Create a great company culture

14No Head Office

15Everyone knows the boss

16Keep walking round the business

17Town Hall meetings

18You run PR

19Weekly newsletter

20Send handwritten letters

21Amazing ways to say ‘Well Done!’

22Have a great bonus scheme

23Celebrate success

24Keep looking for new ideas

25Have a ‘Happy Index’

26Perfect Day

27Communicate in pictures

28The Residential

29The Annual Report

30Never make decisions at a meeting

31Stick to what you know

32Buy poor performers

33Keep management accounts off the Board agenda

34Cash for growth

35Disaster scenarios

36Check the cash every day

37Learn from mistakes

38Summits

39Chairman’s Report 2032

40Agree with your customers

41Be friends with everyone

42Trust your intuition

43Be yourself

44Have a social conscience

45Have a company charity

46Sit down with an A4 pad

47Recognise stress

48Have a mentor

49Spend plenty of time with your family

50Keep it simple

Top 25 Phrases

Introduction

When I was asked to write this book I never realised how much it would teach me about our own business. It made me think. Before the book came into my life I’d never listed the most important elements of our management style. The list didn’t take long to compile. On a wet afternoon on Mustique, when tennis was cancelled, it only took an hour to pick my top 50 management secrets. I emailed them to my son James who added four of his own and I already had the basis of this book.

It was only when I started to think about the detail that I began to learn more about the way we run our business. As I tackled each heading, describing how and why each element works, I was expecting to find it a tough task to find enough good reasons to support my faith in this maverick approach to management. But it strengthened my resolve to keep running our company ‘upside down’.

I have been talking to conferences about ‘Upside Down Management’ for over fifteen years and hardly any delegates have had the courage to follow our example. Some will have found it impossible to persuade their boss to delegate and trust his workforce with the freedom to use their initiative, but I expect most thought I was an eccentric with an interesting idea that was OK for a small family-owned chain of cobblers, but wouldn’t work for them.

My approach to management is probably defined by some of the things that aren’t included in the list of contents. You won’t find budgets, appraisals, big data, market research, psychometric testing or corporate planning away days. To me management is about people not process, it is an art not a science. One of the few things I remember from my university course in Industrial Economics is a definition of profit – ‘the reward for taking risks’. The current emphasis on best practice and governance runs the danger of stifling initiative and failing to recognise that wealth is created by entrepreneurs not administrators.

I considered rating my top 50 business tips at the end of the book in order of importance, but as soon as I started the task I realised why it would be meaningless (but I have picked my top 25 phrases from the beginning of the chapters). All 50 tips are part of a coordinated approach – each one fits our company culture and contributes to our way of working, which I call Upside Down Management. We believe it is the people in our business who create our success; management’s role is to give them all the support they need.

I believe it’s an approach that can be applied to any business and the principles also have relevance to the public sector. Perhaps we can persuade our politicians to promote ‘Upside Down Government’ with the emphasis on giving business the support it needs rather than producing regulations that force us to tick boxes and tell us what to do.

Every tip in this book has made an important contribution to the Timpson business. They all come with my personal guarantee that they really do make a difference. But none works in isolation, they are part of a culture which depends on having a company full of positive personalities. We couldn’t have developed our individual management style without being blessed with an amazing collection of personable and talented colleagues.

I hope this book transmits a bit of the buzz that I get every time I spend a day visiting our shops or chatting to colleagues in our offices and workshops. I also hope that it will convince other business leaders, and even some in government, that the best way to run an organisation is by picking a team of great personalities, trusting them with the authority to do their job in their own way and giving them all the support they need.

I am lucky to have a wholly-owned family business which seldom has borrowings and never has any interference from outside shareholders. This has given me the freedom to discover the huge benefits of running a business by using a combination of initiative, a bit of flair and, hopefully, a lot of common sense. If you are looking for some golden rules to create a great business you won’t find them in the pages that follow. I don’t like rules. If there is a magic formula it is to free the organisation from the constraints of the modern world, ignore regulations and process and be true to yourself by having the courage to be different. You will discover that by avoiding what others see as ‘best practice’ you will not only have more chance of success, everyone in the business will have a lot more fun.

1

Break the rules

If it doesn’t feel right, don’t do it.

Management is an art not a science; break the rules, but stick to your principles.

I am pleased that Nottingham University awarded me a Bachelor of Arts not Bachelor of Science when I completed my degree in Industrial Economics – management is an art not a science. This is much misunderstood throughout business, government and the public services where most managers do their job by following a process and sticking to their rules.

As a result, performance is measured by the ability to follow the process rather than concentrating on the ultimate objective. When recruiting, it doesn’t matter if you pick a poor candidate as long as you follow the proper interview process. Ofsted can withdraw an ‘outstanding’ rating from an amazingly good school simply because a bit of the paperwork is missing. Our well established and highly successful Timpson apprenticeship scheme doesn’t qualify for any government grants because there isn’t an NVQ for cobblers. Young doctors get disillusioned with the NHS because they have invisible bosses who are policing a process that soaks up time that should be spent caring for patients.

As C. Northcote Parkinson predicted, it is getting worse. Organisations become an end in themselves, building a bigger team that spends their time devising rules to tell other people how to do a job they don’t do themselves. Beware any organisation that uses the phrases ‘evidence-based’, ‘joined-up thinking’, ‘working party’ or ‘in-depth study’.

We really don’t have to put up with all the rules that get in the way of doing our day-to-day business. Business leaders only have themselves to blame for allowing lawyers, accountants and so-called ‘professional managers’ to dictate that the only way we can do business is by sticking to the rules and following what they consider to be best practice.

I didn’t realise how bad things have become until we took part in a government procurement process in connection with the proposal to introduce biometric passports.

We were naive, thinking all that mattered was our ability to provide future passport holders with a great service in capturing the new data. But the process was run under strict EU guidelines which eliminated any chance of a company as small as ours competing. It was all done online, no one wanted to see who we are or what we do – the winner was bound to be the team that picked professional advisors, who proved to be the best at following the process. We fell at the first hurdle, but it all came to an end with a change of government. Biometric passports were abandoned, every bidder had to put their hard work down to experience, but the professionals still picked up their fees. What a waste of time, money and talent.

I’ve always been a bit of a maverick, keen to stand my ground when authority flies in the face of common sense. Many times I’ve been told ‘You can’t do that’, a remark that makes me even more determined to do it my way. I got a lot of cautionary advice when we were introducing Upside Down Management. ‘You can’t let each shop charge what they want – you have to have a price list.’ ‘I have a price list’, I replied, ‘and I let each shop charge what they want.’ I have had similar debates over our approach to poor performers who we politely and generously ask to leave without the pedantic production of oral and written warning. ‘You must find yourself in lots of employment tribunals’, I’m told, but we don’t, because we treat our colleagues as human beings rather than part of a process.

I was inspired in this determined quest to ignore perceived best practice and follow my instincts by my wife Alex, whose allergy to process was so acute she never stayed in a meeting for more than an hour. Alex saw way beyond the daily constraints of form-filling (which I had to do on her behalf) and budgeting (she never looked at her bank account). By keeping clear of the conventional ways of business, Alex had a vivid view of the big picture, and a perceptive insight into people’s personality. Alex could never understand why businesses needed to compile long reports or hold meetings that lasted longer than an hour. While most of the world made things more complicated, Alex simply used a bit of intuition and a lot of common sense. Give me inspired instinct rather than measured process every time.

My maverick mood was strengthened by a breakfast meeting with Judith Hackitt CBE, then Chief Executive of the Health and Safety Executive. Our meeting was the result of an article I wrote in my Telegraph column about silly Health and Safety regulations that get companies to spend extra money when they should be making individual colleagues more responsible for their own safety. I found that Judith and I were in total agreement and we went on to talk about PAT testing of electrical equipment. Over breakfast with Judith, I discovered there is no legal requirement: PAT tests are entirely voluntary. I checked with Michelle (the sole member of our Health and Safety department), who confirmed it to be true – no statute talks about PAT testing, it is just the safety consultants who say it is the only way to make sure you are compliant. Michelle went on to tell me that over two years none of our PAT tests (at a cost of £40,000) had revealed a fault – every electrical problem had been discovered and reported by our own colleagues. We now only carry out the tests in shops where the landlord makes it a condition of the lease.

Another, even more bizarre procedure that businesses thought they had to follow, was created in the 1960s when, every fortnight, two women came to our office to clean and disinfect our telephones. They kept coming for years before anyone realised it was a complete waste of money. It’s satisfying to know that we are not the first generation to fall for these snake oil salesmen.

It is particularly frustrating when you come up against silly rules you can’t break, like the security inspection at Fenchurch Street station. Our tiny shop had an open front with a space no more than 3ft × 6ft between the counter and the pavement. Every retailer at the station had to inspect their customer area every hour and sign a form to confirm nothing suspicious had been found. A security guy called every hour to check we had filled in the form. One day our shop colleague had to leave the shop to pick up some shoes from a customer and missed checking the 18 square feet and failed to tick the 10.00am box, so the station manager punished us by shutting the shop for the rest of that day. As the branch didn’t make much money, we solved the problem by shutting the shop for good.

Some of the most stupid rules have been created by employment lawyers who seem to think that there is absolutely no difference between one person and another. Alex was on the interview panel for a new head at our local primary school and came to me with a copy of all the application forms. ‘But they don’t tell me what I want to know’, she said. ‘I don’t know anything about these people – age, sex, home background and everything I would be interested in is missing from their application form and to make it worse they all seem to say exactly the same thing about why they should be given the job.’ To avoid being accused of discrimination we are in danger of discriminating in favour of people who would be no good at the job.

A lot of this modern day ‘best practice’ has been fashioned by accountants, lawyers and consultants, who can be called the rules creation and exploitation sector. Every new bit of legislation brings a new round of breakfast seminars at which professional firms tell us how to keep within the new laws while enhancing their fee income. Don’t you cringe whenever someone stops you in the street to ask ‘Have you had an accident at work?’ By finding a new source of income, lawyers and insurance companies put up the cost of running every other business.

By now you must have guessed that I take a certain pleasure in breaking the rules, but I do so with a purpose. Entrepreneurs make money by using their initiative and being different. If you tread the same path and follow the same process as everyone else you won’t stand out from the crowd and can never create a great business.

We must be the only major retailer that refuses to use EPOS (electronic point of sale), but by denying our central support team the chance of being in total control, we have given our branch colleagues the freedom to give great service. By having the courage to do it in our own way, we have managed to establish a level of customer care that is starting to stand out from other retailers.

The way most companies now do business reminds me of the story of the emperor’s suit of clothes. No one seems to have the courage to blow the whistle on all the process and best practice or see through the plastic world of box-ticking. Be like the little boy who saw the truth – bold business leaders see through convention and follow their convictions. If it doesn’t feel right, don’t do it.

2

Upside Down Management

This is the big idea that made us much more money and established a strong company culture.

Upside Down Management is great for colleagues’ wellbeing.

When I started to read The Nordstrom Way, written about the eponymous American chain of department stores, I didn’t realise that it was going to make such a massive difference to the way we run our business.

The book reveals the secret behind great customer service. Most companies get it wrong. You can’t create great service simply by writing a set of rules, not much is achieved by inventing friendly phrases designed to impress customers, and customer care training courses seldom give the customers the sort of service that will make them go ‘Wow’. The secret is so obvious and so simple, I’m embarrassed to admit that I was running our company for over 21 years before I got the message.

The secret is to trust your colleagues with the freedom to serve each individual customer in the best way they can. Exceptional service, when colleagues sometimes literally go the extra mile, usually occurs when the customer has an unusual request, something that can’t be covered by a set of rules. Nordstrom gave their front-line sales clerks total authority to use their initiative, and they did something else that made a big impression on me. In the middle of the book was a management chart that was upside down. The people who served the customers were up at the top and the chief executive was right at the bottom. The sales clerks are top of the tree because they do the key job that makes the money; everyone else in the company is there to help and support their colleagues on the front line.

Upside Down Management suddenly seemed to me such an obvious thing to do. As a manager who couldn’t repair shoes or cut a key I had, for years, been reliant on colleagues, working in our shops, to do the jobs that made us the money. I was never in a position to tell them what to do, so it seemed far better to abandon the traditional management methods of command and control and concentrate on giving front-line colleagues trust and support.

As soon as I got the message, I was on a mission to turn our management structure upside down, but it took a long time to persuade the rest of my business. Shop colleagues, who I thought would welcome the freedom on offer, were reticent and most of middle management totally disagreed with the whole idea.

The people in our shops were so used to following our rule book that they didn’t believe I was seriously going to give them the freedom to do whatever they wanted. And those that thought it was a good idea were wary of their area managers who had always kept rigid control.

Recognising that people like to have some rules, I just had two: 1) Look the part; 2) Put the money in the till. But to emphasise the degree of trust, I added two guidelines: 1) Anyone, even a new recruit in their first week, can spend up to £500 to settle a complaint, without reference to anyone else; 2) The price list is only a guide – you can charge whatever you think is the appropriate price.

Gradually shop colleagues got the message, but it took me nearly five years to get our area managers to let go. It was difficult to stop them issuing orders. ‘How can I be responsible for the results of my area’, they argued, ‘if I can’t tell anyone what to do?’ Some feared for their job – ‘If I hand over the authority for everything to members of my team, what will be left for me to do?’ I wrote a manual about their new role and we discussed it, section by section, at area manager conferences spread over a period of nearly three years. Gradually some area managers got it and became enthusiastic, while a few uncooperative managers moved on to different roles. It isn’t surprising it took so long to change their attitude; culture change doesn’t happen overnight.

Once our area managers were persuaded, they suddenly realised that their new job was so much better than the old one. Instead of dreaming up all the rules and telling everyone what to do, they now have the time to pick the right people, put them together in strong teams and clear away any obstacles in the way of them doing a great job. With many of those obstacles being problems that occur outside work, our area managers now find that providing a sort of social service is an important part of their job.

Originally I saw Upside Down Management as a way of providing a better service by giving trust and freedom to the front line, but now I know that everyone in the organisation should be trusted to do their job in the way they want. Managers can run their department in their own way as long as they give the same freedom to all the members of their team. The principle even applies to me – I can’t issue orders but I don’t have to follow anyone else’s rules. I might have to comply with the law but there is no need for me to follow ‘best practice’. Like everyone else who works at Timpson I do my job in my own way.

We started Upside Down Management in 1998 and it has worked better with every year that goes by. There are many reasons why it has been so successful. For a start it makes you pick people with a great personality – it soon became clear that dull and pedestrian characters don’t use their initiative. In addition, the business has become bristling with ideas created by colleagues with the freedom to do their own thing. Most of all, our colleagues enjoy coming to work.

Colleagues really like being trusted, they take a pride in running a shop they feel they can call their own. They value the freedom to make decisions and the support they get from a boss who doesn’t issue any orders. When we acquired the Morrisons dry cleaning business in June 2016, the colleagues who transferred to Timpson were amazed that we have such a relaxed approach to business with so few rules and so much freedom.

I wasn’t surprised when a psychologist, who had made a study of the power of delegation, told me that having the freedom to be in control of your working life is very good for employees’ wellbeing. Perhaps that’s why I find it such fun visiting our shops and meeting so many colleagues with a smile on their face. I will never forget the comment from a colleague who joined us when we bought the business where he was working. ‘I was worried at first’, he told me, ‘but after two years I am amazed how much my life has changed. I now look forward to coming to work and I also look forward to going home, where my wife says I’m more relaxed and much better company.’ There is no doubt that a happy workforce will produce better results – another reason why Upside Down Management is so good for business.

But there is another big benefit. When you have established an upside down culture and no longer issue any orders you will find that the business is much easier to run. You no longer have to create a set of standing orders, there is no need to devise a process for everyone to follow. With no rules, your management team don’t have to spend their time checking that everyone is following company policy. By giving every colleague the freedom to do their job in a way that suits them, managers can concentrate on the things that matter – choosing the right strategy, picking people with personality and giving them the support they need to put the strategy into practice.

I promise you it works and it must be the easiest way to run a business.

3

Trust your people

Businesses that are paranoid about theft and security create a negative atmosphere, stifle initiative, prevent proper personal service and undermine company loyalty.

If you can’t trust your colleagues you must be picking the wrong people.

I’ve never understood why so many companies run their business in a way that is primarily designed to thwart the 5 per cent of their workforce who may be dishonest. Organisations go to great lengths to make all transactions totally secure, plugging every possible weakness in their system and, in doing so, produce a detailed control process that strips all the honest colleagues of the chance to use their initiative for the good of the business and its customers.

Although we at Timpson keep a realistic eye wide open, I believe in trusting every colleague. Life is so much easier and the workplace happier if you presume everyone is honest. It is demeaning to people who are subjected to strict security guidelines that presume, given the chance, every colleague will pinch the company’s money. I felt uncomfortable when watching the staff at one supermarket, as they were obliged to open their personal bags for inspection every time they left for home.

This is an example of how a heavy-handed process gets in the way of proper management. Many of the rules are there to cover the management’s back ahead of the next episode of financial loss. Some claim secure systems are required for insurance purposes, and there have been court cases that suggest employers have a duty to take temptation as far away from their employees as possible. But in my experience theft is best detected and controlled by understanding what is going on every day, knowing your colleagues and keeping a close interest in the day-to-day business. At Timpson we still catch someone thieving almost every week but our total loss through internal theft has dropped significantly since we relied on trust rather than regulations. Companies are continually introducing new systems to stop the latest dishonest ploy but they will never be able to stop the determined thief finding another route to pinching money.

I never cease to be amazed at the lengths some people will go to beat the system. One of my favourite scams occurred in Scotland in the 1970s. At that time Tuf shoes with their six-month guarantee were, at 42/9 (about £2.14), the biggest selling men’s shoe and were stocked by nearly every value shoe chain in the country, including Timpson and Freeman, Hardy & Willis (FHW). In a town south of Glasgow the managers of the Timpson and FHW shops came to an arrangement. Just before the annual stocktaking was due to take place at the Timpson branch the manager ‘borrowed’ all the FHW stock of Tuf shoes to enhance the value of his total stock and cover up some of the takings that had slipped into his pocket. Once the stock auditor had moved on to his next assignment the FHW manager got his shoes back with a promise that he would take care of the Timpson stock of Tuf shoes in time for his next stocktake.

Another bizarre and brazen scam took place in a competitor’s shop in south-east England. The shop had two employees, but if anyone went to call they would find only one of them. Visitors were told that the other colleague was on his day off, but in truth he was running their own independent shop down the road. This multiple competitor wasn’t just paying the wages of someone to run their own business, the crafty couple also ordered extra materials and spare machinery parts that allowed them to trade almost cost-free in their little shop round the corner.

I’m not proposing a totally naive approach that believes dishonesty doesn’t exist – there will always be someone trying to take a financial advantage, even if you think you have closed every loophole. Sometimes, when visiting one of our shops I sense that something is wrong. There are some significant signals: the shop manager who has beads of sweat on his brow and can’t look you in the eye, sales figures that shoot up when a mobile colleague covers for the manager’s holiday, shops that look busier than the takings suggest and a manager full of excuses to explain the lack of trade.

True confidence in your colleagues isn’t just about trusting them to put the money in the till – it also includes trusting everyone with the freedom to use their initiative rather than insisting that every job is done according to rigid standing orders. I got a little hint of the culture that exists in some parts of the NHS when I met a management consultant who had been asked to study a number of hospital trusts. ‘I had a big problem’, he told me, ‘the one that performed best against the NHS targets came bottom of the pile when it came to having happy and satisfied patients.’ Sticking to the rules might bring better ratings at your next appraisal but you can’t create a company with personality by laying down strict rules.

A good barometer of culture and management style is the company complaints policy. Process-driven organisations have a comprehensive system that controls the handling of complaints. Colleagues in the front line aren’t trusted with the authority to sort out any problem, however trivial. Any exchange of goods or compensation payout must have the blessing of their line manager who probably needs to talk to the boss who in turn must get permission in writing from Head Office.

The result of this complex complaint chain of command is a collection of unhappy customers (who are now more irritated about the delay than the original complaint) and an overworked and very busy complaints department at the office. I know from experience that trusting your colleagues to take responsibility can save a lot of money.

We seem to live in a world full of suspicion, where no one is to be trusted. Everyone believes it is necessary to follow rules set down by the government, Health and Safety officers, insurance companies, the finance director, lawyers, accountants and the HR department. Too many people now believe that good managers are measured by their ability to make everyone in the organisation stick to the process. I totally disagree – the truly great executives set the strategy, have the charisma to create a positive culture and give their talented colleagues the space to do their own thing.

I hope by now you are getting my message. If you don’t trust your employees they are highly unlikely to trust their customers. About twenty years ago, B&Q, the DIY chain, had a reputation for poor service. There was a good reason: shop colleagues were told that their most important job was to stop customers pinching the stock. They did as they were told, every customer was watched carefully and observed with single-minded suspicion. Stock shrinkage shrank but so did the sales. A move to customer-friendly, more mature sales people made a massive difference to sales without increasing the amount of theft.

Retailers, who fear that every other customer is a threat rather than an opportunity, set several rules to keep the consumer in check. ‘No £50 notes.’ ‘We don’t accept credit cards for payment below £10.’ ‘No refund without a receipt.’ And ‘Only three school children inside the shop at the same time!’

My dream is to have shop colleagues who are so trusted they have the confidence to give £10 to say sorry to a customer whose key doesn’t work; and if someone who has lost their wallet or purse is collecting a shoe repair, to have the sense to say, ‘No problem, take the shoes now and pay me when you’re next near my shop.’

It gives the business a massive boost if you trust your colleagues. Trust their honesty, trust their diligence – timekeeping, determination and loyalty – and trust their judgement. If you can’t trust your colleagues you must be picking the wrong people.

4

Only two rules

The more rules you have, the less important they become.

If you could only have two rules, what would they be?

I