Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

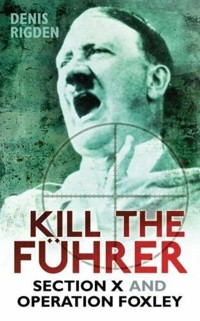

During the Second World War, Britain's top secret Special Operations Executive plotted to assassinate Hitler. A small department of SOE known as Section X had the tantalisingly complex task of investigating how, when and where their plan could be executed. The section also plotted the killing of Goebbels, Himmler and other selected members of Hitler's inner circle. Only Section X and a handful of other SOE staff had any knowledge of these projects, codenamed Operation Foxley and Operation Little Foxleys. As history has shown, these schemes turned out to be pipe dreams. Even so, Section X, renamed the German Directorate in 1944, made a huge contribution to the Allied war effort through their organised sabotage and clandestine distribution of black propaganda. Denis Rigden describes Section X's efforts to discover as much as possible about the intended assassination targets, and questions whether a successful Operation Foxley would have helped or hindered the Allied cause. Based on top secret documents and private sources and illustrated with archive photographs, 'Kill the Fuhrer' is an intriguing insight into the shadowy world of Britain's wartime secret services.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 422

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

KILL THE

FÜHRER

Dedication

I dedicate this book to my supportive family and friends. I am particularly indebted to my wife Roe (Rosemary), who during much of the writing became ‘widow Foxley’.

KILL THE

FÜHRER

SECTION X AND OPERATION FOXLEY

DENIS RIGDEN

First published in 1999

This edition published in 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© Denis Rigden 1999, 2002, 2009, 2011

The right of Denis Rigden, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7574 5

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7573 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

Ebook compilation by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

Contents

Abbreviations and Designations

Introduction

1 Operation Foxley – and much more

2 Hitler’s train a target

3 The Führer’s mountain retreat

4 The tea-house and road plots

5 Foxley thoroughly re-examined

6 Chemicals, bacteria and Hess

7 Four Little Foxleys

8 The Himmler problem

9 Searching for the unfindable?

10 The SOE plotters

11 Sabotage without explosions

12 Larger-scale wreckings

13 Black propaganda

14 Targeting the workers

15 Ungentlemanly warfare

Appendix A Germans opposing Hitler

Appendix B No shortage of would-be assassins

Appendix C The July Bomb Plot

Appendix D The Wolf’s Lair

Appendix E Hitler’s health

Appendix F Climate and topography

Appendix G Skorzeny’s career

Chronology

Notes

Bibliography

Abbreviations and Designations

BSC

British Security Coordination

DAF

Deutsche Arbeitsfront (German Labour Front)

EH

The Foreign Office’s anti-Nazi propaganda branch, taking its name from its location at Electra House

FANY

First-Aid Nursing Yeomanry

FBK

Führerbegleitkommando (Hitler’s bodyguard)

FCO

Foreign and Commonwealth Office (formed in October 1968 by the amalgamation of the Foreign Office and the Commonwealth Office)

FHQ

Führerhauptquartier (Führer Headquarters)

ISK

Internationale Sozialistische Kampfbund

ITWF

International Transport Workers’ Federation

MPGD

Mouvement des Prisonniers de Guerre et Deportés

OKW

Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (German High Command of the Armed Forces)

OSS

Office of Strategic Services

PIAT

Projector Infantry Anti-tank (a British hand-held weapon)

PID

Foreign Office’s Political Intelligence Department

PWE

Political Warfare Executive

RSD

Reichssicherheitdienst

RSHA

Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Security Main Office)

RUs

Research Units (the codename for PWE’s ‘German’ broadcasting stations)

SD

Sicherheitsdienst (SS Security Service)

SHAEF

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force

SIS

Secret Intelligence Service

SOE

Special Operations Executive

STS

Special Training School

The staff officers of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) used Secret Intelligence Service-style designations, instead of their own names, when writing minutes and other documents circulated within the organisation’s headquarters in Baker Street, London. For example, the designation of the Chief (executive head) of SOE was CD and that of the head of the German Directorate was AD/X.

Introduction

Historians of the Second World War could hardly believe what they saw when they picked up their daily newspapers at breakfast time on 23 July 1998. Dominating the front pages were reports revealing something they had never even suspected: that British secret service officers of the Special Operations Executive had plotted to assassinate Hitler during most of the war years.

The media stories on this ultra sensitive Top Secret project, codenamed Operation Foxley, were based on official documents released that morning by the Public Record Office (PRO) at Kew. However, these few hundred papers – many of them written in dull military officialese – were but the contents of only three of the 971 files relating to SOE activities in Western Europe that the PRO was putting on public display for the first time. The media’s sole interest was in Foxley and in a few other headline-grabbing operations, mostly those which, like Foxley, were organised by SOE’s mysterious Section X, responsible for operations in Germany and Austria.

My own research into Foxley began much earlier – in mid-1996 when I was briefed on the operation by Gervase Cowell, the then SOE Adviser to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), who was also Chairman of the Historical Sub-Committee of the Special Forces Club until his death in May 2000. Later, I had similar invaluable help from his successor in the FCO Adviser’s post, Duncan Stuart. As well as providing much biographical information from SOE staff records, Stuart drew upon then unreleased ‘headquarters files’ to give me an overall picture of the many different sorts of sabotage and subversion engaged in by Section X and by the German Directorate, that section’s name during the last six months of the European war.

Although the Adviser to the FCO (a post abolished early in 2002) has efficiently provided historians with all the help he could, the task of researching into what the Special Operations Executive achieved – or failed to achieve – has some distinctive problems. Most of these derive from the SOE’s wartime archives being woefully incomplete. An estimated 85 to 87 per cent of the Executive’s papers now no longer exist. Many were consumed by a fire at SOE’s headquarters – 64 Baker Street, London – shortly after the war (arson was not suspected),1 and some of the records held at SOE’s Middle Eastern regional office in Cairo were deliberately destroyed when the German army came dangerously near. Yet other SOE documents were lost as a direct or indirect result of enemy action in the various theatres of war, or because wartime record-keeping was sometimes haphazard. Undoubtedly, office work was not always well organised at SOE headquarters, where there was no central registry and where each ‘country section’, including Section X, kept it own records in whatever way it thought fit. To top all this, some documents were ‘weeded’ after the war because they were judged to be unimportant and there was a shortage of shelf space. Historians also have problems with some of the SOE papers that have survived. Some are damaged and difficult to read. The ‘economy’ paper of the Second World War was thin and frail. Typing was often single spaced and on both sides of a page.

Even when the extant records are considered there are shortcomings. The documents on Foxley that have survived say nothing about how much planning of this never-to-be operation was undertaken between mid-1941, when Section X was given permission to investigate whether Hitler could be assassinated, and mid-1944, when the matter became a topic of regular discussion in SOE’s governing Council, not just in Section X. Almost all the section’s information about the dictator’s movements and lifestyle must have been gathered during that three-year period. But that was when the section had a small staff who were almost certainly overstretched with work relating to current operations, most of them successful, some spectacularly so. Clearly, in such circumstances, it would have been impossible to allot many resources to the preliminary planning of Operation Foxley and its companion project, Operation Foxley II, which envisaged the assassination of selected members of Hitler’s inner circle, such as Goebbels and Himmler.

A big batch of Foxley and Foxley II documents might, of course, have perished in the postwar fire. It is also possible that these assassination schemes were merely discussed, rather than formally written about, during the ‘hidden’ three years. My guess (I refrain from dignifying it as a theory) is that the research into Foxley and Foxley II during that straitened period was done largely or wholly by Major H.B. Court. The many thousands of surviving SOE personal files do not include his. It seems therefore that his was one of the many such files consumed in the fire. It is, however, known that he was an intelligence officer who, under the SOE symbol L/BX, wrote potted biographies of leading Nazis whom he chose as candidates for assassination. He was always a keen advocate of both Foxley and Foxley II, having none of the misgivings about these schemes that were expressed in 1944 and 1945 by several of his SOE colleagues.

The surviving documents on these projects (or ‘Foxley papers’, as I call them) show that by the autumn of 1944, SOE was in possession of a great variety of information essential to the planning of the proposed assassinations. But there were always gaps in the intelligence picture. For example, the exact locations of Hitler and his principal henchmen at any given time in the last few months of the Third Reich were never discovered. If, by some catastrophic circumstance, the war in Europe had gone on much longer, say into 1946, these gaps might have been filled, and potential assassins might have been selected, trained and sent to Germany.

I wrote this book mainly to tell two stories: that of a highly controversial pipedream, Operation Foxley, and that of Section X. All the many previous books about SOE have either said nothing about the section or have represented it as having achieved little. In reality, however, it made a valuable contribution to the Allied war effort. I think the record needs to be put right.

The Special Operations Executive was created in the deepest secrecy on 22 July 1940. This was only two months after Winston Churchill had succeeded Neville Chamberlain as Britain’s Prime Minister. Ironically, it was the previously ultra-dovish Chamberlain, who in his new post as Lord President of the Council, wrote a War Cabinet memorandum on 19 July describing SOE as a ‘new organisation . . . to coordinate all action, by way of subversion and sabotage, against the enemy overseas’.

Although new, SOE was the product of pre-war secret planning by intelligence and military officers and by experts in propaganda.

In March 1938, shortly after the Anschluss, Hitler’s annexation of his native Austria, the Secret Intelligence Service2 created a small department, Section D, to formulate plans for sabotage and subversive operations in Europe in the event of war. Such schemes would include the selective destruction of key components in trains, factories, power stations and other assets of strategic importance. It was also envisaged that the enemy’s war economy could be seriously damaged through fomenting labour unrest and other discontent. Section D was led by a seconded army officer, Major Laurence Grand, a future major-general. Often wearing a carnation in his button-hole, he was a flamboyant character.

At about the same time the Foreign Office persuaded Sir Campbell Stuart, a Canadian and a former managing director of the London Times, to set up and run a small branch to investigate ways of conducting anti-Nazi propaganda. The branch was called CS, after Stuart’s initials, or more usually EH. (These initials stood for Electra House, the Thames Embankment building in which EH had its offices.) Stuart was an experienced publicist. Towards the end of the First World War he had assisted Lord Northcliffe, the newspaper proprietor, in organising schemes to undermine German army morale.

In October 1938, another future major-general, Lieutenant-Colonel J.C.F. Holland, was appointed to the staff of GS(R), later renamed MI(R), a small research section of the War Office. His assignment, overlapping that of Section D, was to study how to conduct irregular warfare in the conflict against Hitler that he and many other informed observers felt sure would begin soon. A Royal Engineers officer, nicknamed Jo (without an ‘e’), he had won the Distinguished Flying Cross when attached to the Royal Flying Corps in the First World War.

In July 1940, Section D, MI(R) and EH were merged to form SOE. However, responsibility for producing propaganda material, as distinct from its dissemination, was given to the Political Warfare Executive (PWE) in the summer of 1941. Its staff were based at Woburn Abbey, Bedfordshire, and at Bush House, Aldwych, in London.

Churchill tasked the Special Operations Executive to ‘set Europe ablaze’ by helping resistance movements and carrying out subversive operations in enemy-occupied countries. SOE did not do all that the Prime Minister wished it to do. But it did make a big and unreported contribution to the Allied war effort, against both Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan’s expansionist regime. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force, regarded European resistance movements, aided by SOE and American Special Operations, as a strategic weapon. In his view the activities of the disparate organisations comprising the French Resistance shortened the war in Europe by nine months.3

SOE had influence in all the theatres of war except the Soviet Union. Its liaison mission in Moscow received no information from Stalin and was always closely watched by his secret police, the NKVD (forerunner of the KGB). At its maximum size in mid-1944 SOE had a total strength of about 13,000 staff, about 3,000 of whom were women. Nearly half the men, together with a few of the women, worked clandestinely in enemy-occupied or neutral countries, controlling an even larger number of sub-agents. As one of the means of helping SOE staff to conceal the Top Secret nature of their work, they were told to tell friends and other enquirers that they were ‘attached to the Inter-Services Research Bureau.’4

SOE was controlled by the Minister of Economic Warfare – Dr Hugh Dalton until February 1942 and the 3rd Earl of Selborne for the rest of the war. A Labour Party intellectual, Dalton reached the peak of his career when Chancellor of the Exchequer in the postwar Attlee government. He was made a life peer in 1960. Lord Selborne was a former Conservative MP who had held junior government appointments in the 1920s. He had also had important jobs in the cement industry. A grandson of Lord Salisbury, the nineteenth-century Prime Minister, he was nicknamed ‘Top’.

In an undated memorandum, probably written in November 1943, Lord Selborne explained the command structure in which SOE operated. According to a summary of this memo,5 the Minister of Economic Warfare reported direct to the War Cabinet on matters relating to SOE; SOE received directives from the British Chiefs of Staff regarding strategic objectives on which it should concentrate and on the countries to which priority should be given; and from the Foreign Office SOE received guidance on objectives for underground political activity.

SOE’s ultimate controllers were, of course, the British and American political and military leaders. The implementation of grand strategy was the responsibility of the Washington-based Combined Chiefs of Staff Committee, comprising the US Joint Chiefs of Staff and the British Chiefs of Staff. Towards the end of the war the supreme commanders in the various theatres of conflict, in Europe and Asia, exercised more than a little direct control of SOE and other organisations engaged in irregular warfare. For example, SOE received directives from SHAEF, the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force. General Eisenhower was advised on special operations by an SOE officer, Brigadier Robin Brook.6

Members of SOE were recruited from the armed forces, SIS, the business world, academia – indeed, from almost anywhere. They were an odd mixture of professionals and amateurs. There were a few duds among them but most had rare talents and lively minds that they put to good use, often with deadly consequences for the enemy.

Denis Rigden

Chapter One

Operation Foxley – and much more

The Special Operations Executive, Britain’s secret organisation aiding Resistance movements during the Second World War, plotted to assassinate Adolf Hitler. A small department of SOE, Section X, formed in November 1940, had the tantalisingly complex task of investigating how, when and where the deed might be done. Only the staff of that section – renamed the German Directorate in October 1944 – and a tiny minority of others working at SOE’s headquarters in Baker Street, London, knew about this Top Secret project. Even some members of the organisation’s governing Council were unaware of it. However, one of SOE’s principal staff officers and its Chief (executive head) from September 1943, Major-General Colin Gubbins, took a close interest in the scheme.

In mid-1941 the British War Cabinet, Chiefs of Staff and Foreign Office gave SOE permission to study the possibility of assassinating Hitler, and later that year a group of SOE-assisted Polish saboteurs nearly succeeded in killing him when they derailed a train in West Prussia.

By then Winston Churchill’s coalition government had good reason for wanting to remove the heavily guarded dictator from the scene, as the Nazi war machine seemed unstoppable. Its huge forces had inflicted defeat after defeat since September 1939. First, the all but defenceless Poland had been invaded and territorially divided between Nazi Germany and its communist ally, the Soviet Union. In 1940 Hitler had overrun Denmark, Norway, Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg, and the German advance through France had resulted in more than 337,000 British, French and Belgian troops being evacuated from the Dunkirk beaches. The Führer had capped all this by forcing Marshal Pétain’s French collaborationist administration to sign humiliating armistice terms. In April 1941 Hitler’s forces had invaded Greece and Yugoslavia. By 1 June they had occupied Crete, with disastrous consequences for the defending British warships as well as for the British, Commonwealth and Greek troops on the island. The Nazi dictator had by then become so convinced of his own infallible judgment as a strategist that he went ahead with his long-planned invasion of Russia on 22 June.1

After the United States entered the war in December 1941, the American and British political and military leaders continued to hope that Hitler could be got rid of – somehow. However, they were worried that if he were seen to have been assassinated by anybody other than one or more of his closest henchmen, the Gestapo would make the death an excuse to murder vast numbers of actual or suspected members of resistance movements. All and sundry – men, women and children – would perish in such a bloodbath.

By 1943 the tide of the conflict had turned against the Nazis and Allied assessments of Hitler’s impact had changed. Allied leaders were beginning to weigh the relative merits of having either a dead Hitler or a living one: they hoped that he would continue making strategic blunders so catastrophic that he would fast convert himself into one of the Allies’ greatest assets. Indeed, some Allied politicians and generals already regarded him as an unwitting ‘ally’, worth many army divisions. In the last year of the war in Europe, another worry in London and Washington was that Dr Josef Goebbels, the Nazis’ grandly styled Minister of National Enlightenment and Propaganda, would exploit any ‘martyrdom’ of his ‘beloved Führer’ in a desperate final attempt to galvanise the war-weary German nation into fighting harder for an unachievable victory, regardless both of strategic realities and the human and material cost to everybody involved, the Allies and Germany alike.

Despite all these factors inhibiting quick decision-making at the highest political and military levels, SOE was encouraged in June 1944 – perhaps by interest shown by Churchill – to intensify the planning of Operation Foxley, the codename for the proposed assassination of Hitler. General Gubbins arranged that the SIS be involved in the plotting by providing SOE with all available information on the Führer’s travel arrangements and lifestyle; no details about his daily routine were to be regarded as too unimportant to be reported.

Plans for Hitler’s liquidation, either on his private estate in the Bavarian Alps, or when he was travelling by rail or road, continued to be made until he himself settled the Allies’ debate on his future by committing suicide on 30 April 1945, a week before the end of the war in Europe. These unrealised schemes – often the subject of differing assessments by SOE staff officers as well as by their political and military masters – included plans to kill Hitler using SOE agents or bombing by the RAF.

Section X and its successor, the German Directorate, also plotted to assassinate selected members of the Führer’s inner circle. These schemes were codenamed Operation Foxley II and informally called ‘Little Foxleys’. Various Foxley II projects were considered. These included a suggestion, quickly dismissed, that chemical or biological weapons might be used in an ‘attack on a single person’. Another soon abandoned idea was that Rudolf Hess might be persuaded, perhaps under hypnosis, to participate in a Little Foxley.

Those on the Foxley II hit-list at various times towards the end of the war in Europe included: Goebbels, who as well as being Propaganda Minister since 1933 had sweeping powers from August 1944 as Special Plenipotentiary for Total War; SS Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny,2 leader of a ninety-member special detachment that freed Mussolini from custody in September 1943; Heinrich Himmler, head (Reichsführer) of the SS from 1929 and commander-in-chief of the Reserve Army from July 1944; and Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) from January 1943.

In the course of planning Operation Foxley and the Little Foxleys, SOE’s London headquarters received a vast quantity of highly classified information about the day-to-day routines of Hitler and his closest associates. This intelligence included detailed reports on where these Nazis lived and worked; on their travel arrangements; and on many other personal matters relating to their usually luxurious lifestyles, almost always heavily guarded and isolated from the German public on all but rare occasions, particularly towards the end of the Third Reich. All this information, assembled by Allied intelligence organisations, had been obtained over the war years either from prisoners-of-war, some of them former Nazis, or from many conspicuously brave men and women, Allied or German, associated with the resistance movements. If Hitler or any of his principal henchmen had been assassinated, the operatives chosen for that special Top Secret assignment would have needed an extraordinary blend of boundless courage, ingenuity and patience.

The planning of Operations Foxley and Foxley II was only a tiny part of the work done by the SOE staff officers controlling operations inside Germany and Austria. Their main task was to organise sabotage and the secret dissemination of a great variety of black propaganda literature which appeared to be German in origin and was in reality forged in Britain by the Political Warfare Executive (PWE).3

Although there were a number of major operations, such as train derailments and factory wreckings, most of the industrial sabotage comprised small but frequent acts not easily detectable as having been done deliberately. These included the wastage of scarce raw materials and the misuse of machinery, eventually causing its damage or destruction. Detailed information on how workers should engage in such unspectacular routine sabotage was given in literature clandestinely distributed by SOE agents. Section X and the German Directorate also organised what was called ‘administrative sabotage’ – operations to cause bureaucratic chaos, such as the mass circulation in Germany of forged ration cards and coupons for food and clothing (see Chapter Eleven).

In the propaganda sphere, the main aim of PWE and SOE was to undermine the morale of the German armed forces. SOE organised the spreading of literature telling soldiers and U-boat crews how to simulate illnesses, claim sick or compassionate leave, or even desert (see Chapter Thirteen). Similar black propaganda strove to intensifying the existing uneasy relationship between the Wehrmacht and the SS. The aim of yet other forgeries was to reveal the true nature of the Nazi regime to the majority of the German civilian population that still retained varying degrees of confidence in Hitlerism as late as 1944 and 1945 (see Chapter Fourteen).

Unlike the protracted discussions of the assassination schemes, there were no unduly long debates in Section X, and later in the German Directorate, over whether this or that operation involving sabotage or black propaganda could or should be undertaken. This was because SOE and the Allied leaders were agreed that these were acceptable methods of defeating Hitler which were guaranteed to be largely successful – unlike Operations Foxley and Foxley II.

Section X was set up on 18 November 1940 with extremely limited objectives: to establish channels of communication into Germany and Austria as a first step towards creating a network of agents within those countries, and to organise sabotage, initially on a small scale. This tentative planning was based on the assumption, made by the War Cabinet and the Foreign Office, that Hitler’s ‘Greater Germany’ (Germany and Austria) possessed no effective indigenous opposition to his ruthless dictatorship. With a staff of only five, Section X could hardly have had a more modest beginning, though, if circumstances had been different, it should have been SOE’s most important ‘country section’ with a lion’s share of resources.

Section X did, however, have strong backing from SOE’s first Chief, Sir Frank Nelson (1883–1966). As British Consul in the Swiss frontier town of Basle in 1939 and early 1940, he became exceptionally well informed about the Third Reich, particularly about its clandestine activities abroad. After completing his education in Heidelberg, Nelson had a highly successful business career in India, and during the First World War he served in the Bombay Light Horse. President of the Associated Indian Chambers of Commerce in 1923, he was knighted in the following year and sat from then until 1931 as the Conservative MP for Stroud, Gloucestershire.

The section was supervised for nearly a year by another informed advocate of clandestine operations: Sir Charles Jocelyn Hambro (1897–1963), a merchant banker and (only nominally during the war) Chairman of the Great Western Railway. Awarded the MC in the First World War, he joined the Ministry of Economic Warfare (or the ‘Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’ as it was sometimes called) in September 1939. Transferred to SOE in August 1940 he was initially in charge of operations in Scandinavia. He arranged a small amount of sabotage in Swedish harbours serving Third Reich interests, and established contacts with the Resistance in Denmark, a task facilitated by his own family being of Danish origin. From December 1940 to November 1941, he had oversight of Section X and SOE’s French, Belgian and Dutch sections. After a few months as the organisation’s Vice-Chief, he was its Chief from May 1942 until succeeded by General Gubbins in September 1943. Hambro’s greatest contribution to the war effort – and to mankind – was to initiate Operation Gunnerside: the destruction of the heavy water (deuterium oxide) plant in the Norsk Hydro complex at Vemork, near Rjukan, on the night of 27/28 February 1943. If there had been no Gunnerside, the Nazis would have obtained from occupied Norway all the heavy water needed for the manufacture of atomic weapons. Gunnerside, together with related guerrilla actions and aerial bombing, resulted in Hitler losing confidence in his scientists’ research into splitting the atom.

Lieutenant-Colonel Brien Clarke, who later in the war supervised SOE activities in Iberia and much of Africa, was Section X’s first head. But he was succeeded after only a few weeks by Lieutenant-Colonel Ronald Thornley, the section’s guiding force from then until 30 October 1944 when, much enlarged, it became the German Directorate, with Thornley as its deputy head.

Internal SOE documentation from 1940 reflects the British authorities’ prevailing lack of confidence in the fragmented German Resistance (Der Widerstand). For example, Section X minuting referred to the ‘so-called anti-Nazi elements in Germany’ which, it claimed, were ‘in the vast majority of cases neither willing nor able to undertake any subversive activities against the German regime’. Most of the German people were judged to be ‘solidly behind the Nazi leadership’. This situation contrasted sharply with that in the occupied countries. All of these had resistance movements which their respective SOE country sections assisted throughout the war in Europe, providing arms and other supplies, as well as training. Also, many nationals of the occupied countries became SOE agents.

It is clear from all this that Section X faced problems that no other SOE country section had. Trying to establish any militarily worthwhile opposition movement in Germany or Austria was considered to be impossible. It was therefore decided that the section should engage only in ‘subversive activities in the real sense of the word’, ‘sporadic sabotage wherever possible, to alarm the enemy security services and to encourage genuine subversive elements’, and ‘administrative sabotage, which is always a most valuable weapon against methodically-minded Germans’.

In this early period of the war Section X also judged – probably wrongly – that it had no source of recruits for clandestine work in Germany. The estimated 70,000 Germans and Austrians living in Britain in 1939, most of them Jews, were considered unsuitable for active service because of their age or because they had no personal experience of conditions in the wartime Third Reich. Many of these refugees had fled from persecution in the early or mid-1930s.

However, Section X was given invaluable advice – mainly on sabotage and clandestine communications – by three groups of refugees, nearly all of them Germans, who were exceptionally well informed about many of the industries in Germany and the occupied countries. One of these groups, the Demuth Committee (or Central European Joint Committee) received a monthly subsidy from British secret funds – initially £150, but soon raised to £200. The committee was run by Dr F. Demuth, President of the Emergency Society for German Scholars in Exile, from 6 Gordon Square, London. He was in contact with about forty refugees, mostly German Jews, who in prewar days had held senior positions in industry, commerce or banking.4 His discretion in performing this go-between role deservedly earned praise from the War Office and Britain’s counter-espionage service, MI5. However, his contacts were not always handled well. For example, one of them, Dr J. Seligsohn Netter, a former chairman and managing director of the Wolf Netter and Jacobi Werke, was told to visit his ‘nearest labour exchange’ when he offered his services to the Ministry of Economic Warfare in December 1940.

Section X’s other exiled special advisers belonged either to the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITWF) or the Internationale Sozialistische Kampfbund (ISK), a small and unusual socialist party, most of whose members were German, the others being Swiss, French, Belgian, Dutch or Scandinavian. The ITWF (called the International Transport Federation in some SOE documents) moved its head office from Amsterdam to London shortly before Hitler invaded Holland. By 1940 those German ISK members still in Germany were either in concentration camps or, if at liberty, were actively anti-Nazi whenever possible. The ISK, whose members were teetotal, vegetarian and in other ways ascetic in their personal lives, was the only mainly German political party that gave Section X any significant amount of help. Section X particularly valued the advice of two ISK leaders, René Bertholet in Switzerland and Willi Eichler in London, who had contacts with the Swiss secret service.5

One of the Section X’s first decisions was to appoint its own representatives in SOE missions in important neutral countries, such as Switzerland and Sweden, and to ask other country sections of SOE to assist it in penetrating Germany – clearly, something it could not do on its own. However, these country sections were preoccupied with their own efforts to establish links with resistance groups and refused to give Section X enough of the help that it needed. The section was therefore almost always forced to rely on its own limited resources – its own representatives in the neutral countries and its own agents, for a long time few in number.

In December 1940 Section X arranged with the British censorship authorities to receive copies of all correspondence relating to certain individuals in whom it was interested. Postal censors worked in a central bureau in Liverpool and in many other offices in Britain and overseas. In Bermuda a mass of postal, telegraphic and radio traffic between the western hemisphere and Nazi-occupied Europe was intercepted by an outstation of British Security Coordination (BSC). Established in New York in August 1940, BSC represented SOE and SIS interests in the western hemisphere, and shortly after the US entered the war in December 1941 it became their chief liaison office with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)6 and later also with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. British Security Coordination was headed by a personal representative of Winston Churchill, William Stephenson. Knighted in 1945, he was a Canadian-born millionaire businessman, electronics pioneer, and in the First World War, an ace fighter pilot.7

In January 1941 Section X began a regular and fruitful dialogue with MI9, the branch of the War Office’s Military Intelligence Directorate that organised escapes from prisoner-of-war camps in Germany and the occupied countries. Section X arranged to be shown MI9 documents that would be helpful when planning operations. The section also compiled a questionnaire for use by MI9 when debriefing former prisoners of war after their repatriation. Many of these men provided intelligence valuable to Section X.

However, the section initially received little useful information from SIS. This was partly because almost everything related to the gathering, assessment and distribution of political, military and economic intelligence was badly organised in the immediate pre-war years. As a result, the Foreign Office, the armed services’ ministries and the intelligence community often failed to coordinate their efforts during the war. Another problem was the under-funding of services related to defence. In 1935, at the height of the Abyssinian crisis, the head of SIS, Admiral Sir Hugh ‘Quex’ Sinclair, complained that financial stringency had forced his organisation to abandon activities in several countries that had been bases for obtaining information about Fascist Italy. He added that SIS’s budget had been so reduced in recent years that it now equalled only the normal cost of operating one destroyer in home waters.8

In July 1938, Sinclair defended criticism of SIS from within Whitehall. He admitted that except on naval construction, where it was ‘excellent’, SIS’s intelligence on military and industrial matters was at best ‘fair’.9 Already handicapped by having only a thin spread of agents in Europe, SIS suffered severe setbacks shortly before the war. As a result of the Anschluss, its head of station in Vienna was arrested, and its network in Czechoslovakia was broken up after the Nazi seizure of Prague in the spring of 1939. In the first two months of the war, SIS lost its Berlin, Vienna and Warsaw stations, and, during the Soviet–Finnish ‘Winter War’ of 1939–40, the stations in Helsinki and the Baltic States had to take refuge in Stockholm. The Nazi conquests in 1940 caused SIS to lose its stations in Oslo, Copenhagen, Paris, Rome, Brussels and The Hague. By early 1941 all the Balkan stations had been compelled to move to Istanbul, and within Europe SIS had become heavily reliant on its presence in four neutral countries, Switzerland, Sweden, Portugal and Spain.10 It was against this background of few resources and severely limited initial objectives that Section X began its work. However, before examining the section’s activities in detail, it is worth mentioning an operation which the SOE officers in London did not plan but which was in line with Allied policy on sabotage. More importantly, this operation gave Section X food for thought when, in 1941, it began studying whether Hitler could be killed during one of his journeys by rail.

Chapter Two

Hitler’s train a target

The SOE documents on Operation Foxley record that a group of Polish Resistance fighters nearly succeeded in killing Hitler in the autumn of 1941 when he was travelling in his personal train, the Führerzug, in West Prussia – an area mainly comprising the pre-war Polish Corridor.

This party of highly trained saboteurs, whose orders were to destroy any fast train, not necessarily Hitler’s, had laid several kilograms of explosives on the railway line between Freidorf and Schwarzwasser about 20 to 30 minutes before the Führerzug was due to race by. However, for reasons unknown, Hitler’s train made an unexpected stop at a nearby station. But the operation was far from being wholly unsuccessful as another train was let through and it detonated the charges, killing 430 of the Germans on board. They were probably SS personnel and others closely associated with the Nazi regime, although the Foxley papers do not say so. Much material damage was also done, as it took two days to unblock the line. The Poles had been able to place the explosives because the railway police (Bahnpolizei) who guarded the track were less vigilant in 1941 than they were later in the war. Armed with rifles and hand grenades, they patrolled the line periodically but spent most of the time near the points and the already heavily guarded signal boxes.

In 1941 the members of the Polish Resistance engaged in railway sabotage were organised in twelve-member detachments, each comprising a radio operator, six men who laid the explosives, and five who acted as lookouts. Each detachment – there was one for every district (kreis) – had a short-wave radio set used to communicate with the Polish Resistance headquarters and with other sabotage detachments, and to detonate the charges from a distance of 400 metres. The charges were attached to the rails by spring clips.

Polish saboteurs played a major role in disrupting Nazi railway traffic to the eastern front. They destroyed or seriously damaged an estimated 6,000 locomotives and an unknown number of other rolling-stock. These guerrilla actions, together with much else done by members of Poland’s heroic resistance movement, benefited greatly from assistance by SOE in the form of training and the clandestine dropping of military supplies from the air.1 During the war years 485 successful drops were made on Polish soil, the first on 15 February 1941. This was a pioneering venture undertaken at great risk to the RAF Whitley bombers involved, since never before had SOE arranged such an airlift on to any enemy-occupied territory.

All this was made possible by the close relations established between intelligence officers serving Poland’s exiled government (in London after a short period in Paris) and Colin Gubbins, the future major-general and executive director of SOE (from September 1943). A specialist in irregular warfare, he had been Chief of Staff of a British military mission to Poland in the summer of 1939. From there he had brought back to Britain a Polish time pencil, a device that detonated a plastic explosive charge after a pre-set period ranging from ten minutes to thirty hours. Invented (ironically) by the Germans in the First World War, the time pencil had been improved by the Poles and was perfected by SOE’s Station IX, a secret research establishment at The Frythe, a former hotel in Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire. Training in the use of the time pencils, as well as in many other sorts of industrial sabotage, was given to SOE agents at another Hertfordshire location, Brickendonbury Manor (Station XVII). The time pencils contributed significantly to the Allied war effort in enemy-occupied countries, not least in Poland. More than 12 million of them were manufactured during the Second World War.

Hitler’s train, which was so nearly destroyed by Polish saboteurs, was a great source of interest to Section X. Between 1940 and 1944 SOE assembled a wealth of detailed information about the Führerzug and the other Sonderzüge, the Special Trains used by only a few members of the Nazi leadership and their entourages. These favoured men included Himmler, Göring, Joachim von Ribbentrop, the Foreign Minister, and Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Hitler’s sycophantic principal military adviser and nominally Chief of Staff of the High Command of the Armed Forces (OKW). The Führerzug, a streamlined express train, was given to Hitler by a group of industrialists. He used it as a mobile headquarters and when making his few visits to fellow dictators – Benito Mussolini, head of the Italian Fascist regime, and General Francisco Franco of Spain.

The train was made up of three sections which were linked together during only part of the journeys. The front section (Vorzug) was codenamed ‘Kleinasien’; it carried some members of Hitler’s staff. The second and main section (Hauptzug) was codenamed ‘Amerika’ and was where he nearly always travelled, accompanied by his immediate entourage, including twenty or so members of the SS-Führerbegleitkommando, Hitler’s escort detachment. The rear section (Nachzug) was codenamed ‘Asien’ and carried other security personnel.

The Führerzug was long. For example, the Hauptzug section alone comprised two locomotives and fourteen coaches when travelling in 1940 between Freilassing, Salzburg and Hitler’s various headquarters (FHQs). Anti-aircraft guns were mounted on the first and last coaches. The second and third coaches were the Führerbegleitkommando’s quarters. The train staff had accommodation in coach four. Radio and telephone equipment were in the fifth coach. Hitler’s secretariat was in the sixth, and Martin Bormann and his staff were in the seventh. A dining car and kitchen comprised the eighth. Adjutants occupied the ninth, and the tenth was Hitler’s saloon coach, at the entrances to which two bodyguards were always on duty. ‘Various high personages’ (Section X’s description) were in the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth coaches.

At other times the Hauptzug section of the Führerzug was believed by Section X to have between six and twenty coaches. In 1943, during the Russian campaign, it had two locomotives and ten or eleven coaches defended by surface artillery as well as anti-aircraft guns.

Railway police, usually armed with revolvers but sometimes with rifles or machine-pistols, and detachments of train and local Gestapo, some in civilian clothes, were on duty on the platforms wherever the Führerzug stopped at stations. Whenever Hitler left the train, such as for stops lasting up to half an hour, he was surrounded by bodyguards. Early in the war, when Goebbels was still successfully brainwashing much of the German population into believing that his idol was worthy of hero-worship, admiring crowds were allowed to go right up to Hitler’s personal coach at stops en route. But, Section X estimated, by 1944 members of the general public were being kept at a distance from the train, and even the railway workers servicing it were not permitted to loiter unnecessarily.

Information about the routes and travel times of the Führerzug and of the other Special Trains (Sonderzüge) was a State secret. The Nazi-controlled central management of the railways, in both Germany and the occupied countries, telegraphed unpublished timetables to its subordinate area offices and to the stations concerned. The arrival of a Special Train was announced by number only, with the seeming intention on some occasions of giving the misleading impression that it was a goods train.

However, Section X did not believe that the Nazis went one step further still and ran ‘duplicate Führerzüge’ – trains disguised to look like the real Führerzug. This belief was based on information from one of Hitler’s former servants who often travelled on the Führerzug until mid-1940, and on subsequent evidence from other sources that such ‘duplicates’ were never seen on the eastern front. The nearest approach to any such deception was the running of an advance train, which, according to three well-informed Austrian railwaymen, always went some distance in front of every Sonderzüg, at least in Germany. This advance train had one or two coaches carrying railway police sent to reinforce their local contingents. Running a ‘duplicate’ would never have fooled the general public for long, as the Führerzug (and the other Sonderzüge) were distinguishable from ordinary trains by their luxurious coachwork, larger windows, and wider concertina gangways between coaches.

Section X also assembled detailed information about the servicing and provisioning of the Special Trains. For example, on Ribbentrop’s train the exterior of the coaches, excluding the roofs, was washed outside Salzburg station by six French women and the interior of the coaches was cleaned by railway workers, presumably Austrians or Germans. The Führerzug was usually serviced at the Schloss Klessheim sidings in a western suburb of Salzburg by Führerbegleitbataillon personnel thought to be fanatically loyal to Hitler, but the train was also seen on sidings at Salzburg beside Göring’s Sonderzüg, close to a place normally reserved for Ribbentrop’s train. Section X knew about the cafés and other locations where the various train personnel spent their leisure time.

It also knew that water for drinking and cooking purposes was supplied to the Führerzug at stations where it stopped. Hydrants were connected either to the train’s fresh-water tank on the dining car roof or to water cocks on either side of the train. At Anhalter railway station in Berlin, beer, mineral water, chocolate, malt and coffee were taken on board in sufficient quantities to last four to six weeks. Meat, vegetables and fruit were usually supplied at Salzburg. Arthur Kannenberg (1896–1963), a senior official of the Reich Chancellery in Berlin and a former cook, waiter and accountant, was responsible for ordering this food; Hitler’s was specially brought from the Chancellery or from the Berghof, his villa on the Obersalzberg in the Bavarian Alps.

The level of defence on the trains was also thoroughly researched by Section X. This was information that would be essential if any attack were to be made on the Führerzug. The similar sounding Führerbegleitkommando and Führerbegleitbataillon had different but complementary functions. Members of the Führerbegleitkommando (or FBK, Begleitkommando des Führers) were bodyguards accompanying Hitler wherever he went. The Führerbegleitbataillon, a unit of the Division Grossdeutschland, usually provided guards at Hitler’s headquarters but were otherwise not directly concerned with his personal safety. The FBK was formed in February 1932, eleven months before Hitler came to power. By 1944 it had 143 SS personnel. Responsibility for his safety was also entrusted to an even more important and more sinister organisation, the Reichssicherheitsdienst (RSD), which by 1944 had 250 personnel. The RSD had wide-ranging powers of investigation and prosecution as well as responsibility for the safety of not only Hitler but also the other leading Nazis. It was formed early in 1933 as the ‘Command for Special Duties’ but was renamed the RSD two years later. Its leader throughout was a former police lieutenant, Johann Rattenhuber (1897–1957), eventually as an SS-Gruppenführer (major-general).

With all this information on the Führerzug and the other Special Trains, and undeterred by the Polish saboteurs’ failure to kill Hitler in 1941, Section X was in 1944 studying the possibility of assassinating him when he travelled to Berlin from Berchtesgaden or Schloss Klessheim, or from Munich to Mannheim.

On the first of these journeys the Führerzug stopped at Landshut, Regensburg, Hof and either Halle or, less often, Leipzig. Also the Führerzug and the other Sonderzüge sometimes stopped at Juterbog or Luckenwalde where Hitler, Himmler, Ribbentrop and other leading Nazis might disembark with their entourages and complete the journey to Berlin in cars. The Führerzug travelled between 90 and 120 kilometres per hour and went through two tunnels. On the Munich–Mannheim route the train was ‘believed’ (Section X’s word) to pass through Augsburg, Ulm, Stuttgart, in which there were two tunnels, and Heidelberg.

Four dissimilar methods of assassination based on information about the Führerzug were proposed: shooting Hitler, poisoning him, blowing up the Führerzug in a tunnel or derailing the train when it was travelling on the surface.

The first plan envisaged shooting Hitler beside the Schloss Klessheim railway sidings when he was stepping out of his car to begin a rail journey. Unfortunately, Section X did not know whether his motorcade took a left-hand or a right-hand fork after leaving or passing the Schloss. This imposing eighteenth-century palace2 on the western edge of Salzburg had been used since January 1944 as part of one of Hitler’s personal headquarters (Führerhauptquartier – FHQ) because the advancing Soviet army was threatening the Rastenburg FHQ in East Prussia.3

Schloss Klessheim, outlying buildings and the railway sidings were protected by an estimated 1,250 troops equipped with antiaircraft guns, searchlights and armoured cars. If the left-hand fork were taken, the road ran towards sidings beside a wood. Though thickly leaved in summer, this wood, made up largely of deciduous trees, might not provide much means of concealment in winter. Nevertheless, Section X officers thought, perhaps too optimistically, that there was ‘adequate cover’ for a sniper with a rifle, or a small party armed with a PIAT anti-tank gun,4 to be hidden at the edge of the wood (and the road) opposite a building at the north-western end of the sidings. Thus precariously positioned, the sniper or PIAT handlers would shoot Hitler from a distance of less than 90 metres as he got out of his car.

In the event of his motorcade taking the right-hand fork after leaving or passing the Schloss, even greater difficulties would have been encountered. The Section X officers thought that in that situation Hitler would probably get out of his car near a building at the southeastern end of the railway sidings. This would place him well over 270 metres from the point of fire. He would therefore be too far away for a sniper to be sure of killing him, but, the officers believed, he would ‘probably’ be within range of a PIAT. This seems another example of Section X’s unjustified optimism, as according to The Oxford Companion to the Second World War, the PIAT, manufactured from mid-1942, was ‘effective’ to only 90 metres.

A second plan relating to the Führerzug considered the possibilities of poisoning. Section X thought that it would be impossible to poison the Führerzug’s drinking and cooking water, or in other ways interfere with the train, when it was standing overnight in the Schloss Klessheim sidings. This caution was almost certainly justified, as Klessheim was (as described in the Foxley papers) ‘a private station and not open to the public’ and the train was guarded and washed by Führerbegleitbataillon troops. However, the idea of ‘doctoring’ the water when the Führerzug was parked in the sidings of Salzburg railway station was not rejected out of hand. Section X believed that the train was occasionally serviced there; in July 1944 it was reportedly seen standing alongside Ribbentrop’s Sonderzüg.