15,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

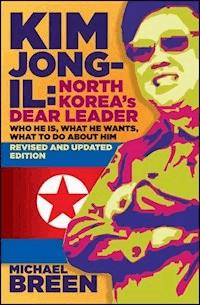

An expert on North Korea sheds new light on the enigmatic tyrant From his goose-stepping military parades to his clownish macho swagger, North Korea's Kim Jong-il is an odd amalgam of political cartoon and global menace. In charge of a nuclear arsenal he's threatened to use against the U.S. and Japan, the man, his motives, and the mechanisms of his absolute control over a country of twenty-three million people remains shrouded in mystery. In this second edition of his bestselling Kim Jong-il, Michael Breen, a leading expert on North Korea, dispels common myths and fallacies about the so-called "Dear Leader," while turning a spotlight on the man to reveal his true nature and the nature of his hold over a country ravaged by poverty and famine. * Looks at Kim from a broad perspective, unlike most other books that cater exclusively to those interested in policymaking and international relations * Features new information about succession plans, as well as the latest scoop on the mounting pressure among world leaders to thwart North Korea's nuclear ambitions * Illustrated with rare photographs of Kim and his regime Highly accessible and suitable for anyone interested in learning more about North Korea, it's government, and its leader, Kim Jong-il unravels the mysteries, the myths, and the fallacies about the man in charge in ways that will entice even the harshest critics.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 329

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1: Dark Country

Pool of Darkness

Who Is Charlie Chaplin?

Teaching Journalists

Chapter 2: Two States

Kim Il-sung and the Division of Korea

The Cold War

Chapter 3: Going Nuclear

North Korean Aggression in 2010

Weapons of Mass Destruction

Anti-Americanism in South Korea

Chapter 4: Dear Boy

Childhood and War

Teaching the Teachers

Chapter 5: Dear Successor

How Kim Jong-il Was Chosen

Dear Leader and His Loves

Chapter 6: Portrait of the Artist

Limiting the Joy

Kim Turns to Kidnapping

Chapter 7: Is Jong-il Evil?

Kim the Micromanager

The Temper and the Humor

How His People See Him

The Malignant Narcissist Theory

Chapter 8: Country of the Lie

The Secret to North Korean Communism

Race-Based Nationalism

Trouble with the Truth

The Control on Information

Chapter 9: The Gulag

The Gulag

The Story of Lee Soon-ok

Kang Chol-hwan: Child of the Camps

Chapter 10: The One Fat Man

A Journey through Russia

The Struggle for Food

Escaping to China

Chapter 11: Submerging Market

Looking in Vain for Signs of Change

Tourists from South Korea

Business Zones for China and South Korea

Chapter 12: Follow the Money

Chapter 13: Collision Course

Korean Names

Recommended Reading

About the Author

Index

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons Singapore Pte. Ltd.

Published in 2012 by John Wiley & Sons Singapore Pte. Ltd., 1 Fusionopolis Walk, #07-01, Solaris South Tower, Singapore 138628.

The first edition was published in 2004.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as expressly permitted by law, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate photocopy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center. Requests for permission should be addressed to the Publisher, John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte. Ltd., 1 Fusionopolis Walk, #07-01, Solaris South Tower, Singapore 138628, tel: 65-6643-8000, fax: 65-6643-8008, e-mail: [email protected].

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Neither the author nor the Publisher is liable for any actions prompted or caused by the information presented in this book. Any views expressed herein are those of the author and do not represent the views of the organizations he works for.

Other Wiley Editorial Offices

John Wiley & Sons, 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

John Wiley & Sons, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, P019 8SQ, United Kingdom

John Wiley & Sons (Canada) Ltd., 5353 Dundas Street West, Suite 400, Toronto, Ontario, M9B 6HB, Canada

John Wiley & Sons Australia Ltd., 42 McDougall Street, Milton, Queensland 4064, Australia

Wiley-VCH, Boschstrasse 12, D-69469 Weinheim, Germany

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-1-118-15377-2 (Paperback)

ISBN 978-1-118-15379-6 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-1-118-15378-9 (Mobi)

ISBN 978-1-118-15380-2 (ePub)

For Han Jin-duk

Whose life cannot be given back

Preface

An American diplomat in Seoul once aptly described North Korea as an “intelligence black hole.” Its submarines can be tracked, its pedestrians followed from space, and its newspapers read. But how does the analyst sift this material if he doesn’t know how the captains get their orders, what the pedestrians talk about when they disappear into buildings, or what’s in the reports sent to decision makers?

Now consider how dangerous North Korea is. It is dedicated, in its ruling party’s constitution at least, to overthrowing its rival, South Korea, and unifying the peninsula. It has one of the world’s largest armies and is an enemy of the United States. The allies have long had the technical means to detect the build-up to a conventional attack. The danger of North Korea used to be expressed in terms of diminishing warning times, from days to hours. Now, however, North Korea is a nuclear-armed state with an arsenal of biological and chemical weapons and a large number of special forces that could be on top of the South Koreans before they knew it. Recent incidents came with no warning: In 2010, a South Korean frigate was sunk with the loss of 46 lives, in a nighttime attack that was almost certainly North Korean; in the same year, four people were killed when North Korean artillery shelled a South Korean island; in April 2011, the computer system at a South Korean financial institution crashed in what investigators and intelligence officials claimed was a North Korean cyber attack.1

Media analysts claim such attacks represent demands for cash, positioning before negotiations, warnings not to be ignored, nonspecific attention seeking, unifying the people after the announcement about succession of the next leader, muscle-flexing by the next leader, revenge for an earlier clash that the North Korean navy lost, and so on. In short, they don’t know. They don’t know why these attacks happened, couldn’t tell they were going to happen, and don’t know what will happen next.

The heart of this dark mystery for the past two decades was Kim Jong-il. Until his death in December 2011, he was the absolute leader of this nation of twenty-three million, a role he inherited in 1994 from his father, Kim Il-sung, who ruled from the foundation of the country in 1948. As Kim Jong-il ailed—he had a stroke in 2008—he identified his third son, Kim Jong-un, as the man to succeed him. The world got its first long look at this young man, who is still in his 20s, at his father's funeral, where he was flanked by elderly party leaders and generals in uniform. Scenes of sobbing North Koreans, some of them sincere and some no doubt making sure they appeared duly miserable, were played around the world. Analysts made a stab at answering the question on everyone's mind: How will the new Kim fare? No one knows.

Kim Jong-il died, allegedly of a heart attack on his private train brought on by hard work, the week the updated version of this book reached the stores. We may have to revise these lines about the new leader a few months later. Or, we may be asking the same questions about the same North Korea at Kim Jong-un's funeral 60 years from now. What we can say with some certainty, though, is that the young Kim will have to defer, possibly even take orders from, those old men around him for some time to come. If he crosses them, and certainly if he tries any reforms in the near future, he will himself be pushed out. That is because the North Korean elites share a dilemma: They know that if they open their country, as they must to join the rest of the world and improve the welfare of their people, they will be letting in the virus that will ultimately destroy them. Their choice is to protect themselves and keep their people down. For as long as they do this, they need Kim Jong-un. Thus they will continue with more of the same. And that means that, just as Kim Jong-il kept the memory of his own father alive—indeed, he appointed the late dictator as president-for-eternity—so Kim Jong-un must call on his father's ghost to justify his own leadership. Kim Jong-il, we may say, hasn't gone yet. This book is about him.

I write from Seoul, the capital of South Korea. My home is a two-minute walk from the presidential Blue House. This perspective places me firmly in favor of talks over warfare. My views and feelings toward Kim and North Korea are influenced of course by proximity, but they are at the same time distinct from those of my neighbors inasmuch as I am not Korean. The two Koreas are rare nations in the world that have had almost zero racial mixing for several thousand years and where therefore nationality is defined with reference to race. North Korea’s version of this is as politically incorrect in the modern world as it gets. The particular temptation for South Koreans in considering Kim Jong-il is the narcotic of racial brotherhood, which engenders eventual forgiveness of even the most egregious North Korean offense. This aside, South Korean attitudes that were shaped under dictators by propaganda, tales of the 1950–1953 war, and proximity, have shifted with democracy and wealth. South Koreans have extended themselves to forgive, propose reconciliation and offer help, and examine themselves when it is rejected. This journey leaves them both drawn to and repulsed by North Korea, swinging from a preference one day for liberal engagement and food aid to the conviction the next day that Kim Jong-il must be taken out. They find his regime loathsome in regard to its human rights and inability to care for its people and manage the economy. But they fear the chaos of change. They also worry about the demonizing of Kim by foreigners, a necessary precursor to military action, because they live too close. Sometimes, too, they are embarrassed because he is, after all, Korean.

North Korea is a country you can be a foreign specialist in, not just without speaking the language, but without even visiting. I can claim to have been to North Korea several times. Indeed, I was in a group that had lunch with Kim Jong-il’s father, Kim Il-sung, in 1994. But, besides the photos, which are good for credibility and storytelling, I am not sure frankly how much knowledge and understanding was gained by actually being there.

When I decided to go in the late 1980s, after the country opened up to Western tourists, a Western diplomat experienced in communist states gave me some tips on dealing with the black hole phenomenon. “They won’t tell you anything,” he said. Or they’ll lie. My first guide would claim there was no crime, a lie (or a delusion because newspapers have no police or court reporters). “You’ll have to figure things out from what you see.” For a reporter used to depending on people’s words, this was a departure. The first impressions—oxen in the fields, absence of commerce, wacky political slogans, children marching to school singing revolutionary songs, decrepit industry—made me wonder why we were afraid of this sad country. “Count the wires between telegraph poles,” the diplomat had advised. “See what kind of rolling stock is in the train stations.”

On two of my trips, I was with business people. One time we visited a soft drinks plant. I paused at the place in the line where a machine pressed caps down on the bottles. There was a large bin under it with broken bottles. I couldn’t figure out why. “These bottles aren’t sitting straight on the line,” one of the businessmen said. “That’s because there are bubbles sticking out of the bottom. They’re at an angle and, when the machine rams the cap down, it cracks them.”

This mundane exchange explains how outsiders become hooked on North Korea. It alerts them to the mystery in every detail. Here’s how nonideological fellow travelers get seduced: Yes, North Korea is run by a nasty dictatorship, but from a position of safety, many foreigners cherish their association with it because of how it makes them feel about themselves. Thus engaged, they develop sympathy for the people who are figuratively blindfolding and spinning them around. Once, in the mid-1990s, when the foreign press was reporting rice shortages, the Koryo Hotel in Pyongyang was serving two bowls of rice with each meal, proving as far as I was concerned that the reports were wrong. “No, it confirms them,” a South Korean friend later explained before I went into print with my discovery. “They know you won’t eat it all. They’re taking the leftovers home.”

Welcome to North Korea, the black hole where information and mobility are so restricted that citizens don’t know what’s going on outside and no one knows what’s going on inside. We believe, but are not sure, that as many as three million people may have died of famine in the 1990s, that hundreds of thousands have fled to China, where they live secretly and in fear of deportation and punishment, and that millions of those who remain depend on international food shipments. How is a humanitarian crisis on this scale possible in the twenty-first century in the center of booming northeast Asia? The answer lies with Kim Jong-il.

The aim of this book is to introduce him, tell his story as much as we can, and figure how he squares the fact that citizens can be sent to the gulag for reading Le Monde with his personal preference for a good French wine. In doing this, we will explore the question of how he manages to hold on to power. Above all, we need to figure why he is able to scare the civilized world with his weapons of mass destruction. Kim Jong-il’s nuclear program puts North Korea on a collision course with the United States and its allies. As hard as it is to believe from the sophisticated malls of Seoul, Tokyo, and Beijing, this situation is very likely to end in warfare. The world has a stake in understanding what it can about this man and his country.

Korean Spelling and Names

Korean doesn’t lend itself to perfect rendition into English spelling, which is why you will see, in the bibliography, for example, Kim Il-sung spelled Kim Il-song in some cases with a little symbol above the o. In some other book titles, you will see Jong-il spelled Chong-il. But I’m going with the familiar. With North and South Korean places, I am using local spellings minus diacritic marks.

As far as Korean names go, it’s a one-syllable surname first (two in rare cases), followed by a personal name of either one or two syllables. So, Kim Il-sung is Mr. Kim, not Mr. Sung. The exception here is the first South Korean president who is generally known in English as Syngman Rhee. In Korean, he is Rhee Syngman. There’s no fixed style but I’m hyphenating the two-syllable names with the second one lowercase, that is, Kim Jong-il as opposed to Kim Jong-Il or Kim Jong Il. The only exception is in the bibliography. Some Koreans invert their names for simplicity. Again, the only examples here are in the bibliography or in quoted excerpts.

There are only 270 surnames to go around the 75 or so million Koreans in the world, and many of those are obscure. It was only about 100 years ago that all Koreans were required to have full names and they naturally tended to choose ones associated with the upper classes. Hence the fact that about one-fourth today are Kims, and another quarter Lees, Parks, Chois, or Chungs. To assist the reader, I’ve provided a cast of characters at the end of this book.

Notes

1. “Cyber Terror against NH,” The Korea Times, May 4, 2011.

Acknowledgments

Some who helped with this book are officials, frequent visitors to North Korea, and defectors who for obvious reasons must remain anonymous. Others I can name include: Marceli Burdelski, Jack Burton, Brent Choi, Barbara Demick, Kwak Dae-jung, John Larkin, Donald Macintyre, Tim Peters, Sohn Kwang-joo, Jay Solomon, Norbert Vollertsen, Andrew Ward, and Roland Wein. My thanks to them all. For additional help, I am grateful to Chi Jungnam, Ken Kaliher, Kim Mi-young, Kim Yooseung, and Ryoo Hwa-joo. I will make special mention of Aidan Foster-Carter, whose copy I had the good fortune of editing some years back when we produced a monthly called North Korea Report. The original suggestion for this book came from Nick Wallworth, my publisher at John Wiley & Sons, when I approached him with a different project. I’m grateful he had me change course.

Chapter 1

Dark Country

The first time I went to North Korea, a diplomat told me, sotto voce, “The lid’s going to blow off this place.” That was in April 1989. Living there made him an expert. Later that year, the pot of revolution would boil over elsewhere. A democratic revolt tore through Eastern Europe, ending decades of communist rule and Soviet control. In China, students called for political reform and occupied Beijing’s central Tiananmen Square for a few giddy weeks before a merciless military crackdown. But none of this prompted the slightest change for North Koreans. More than 20 years later, their lid remains firmly on.

Why? The answer lies with one man, Kim Jong-il. His story reveals why the North Koreans have not dumped their brand of communism onto the ash heap of history despite the example in prosperous, free South Korea of a better way to be Korean. It is not a story easily pieced together. Information that circulates normally in other countries is classified in North Korea. Hence the rush in 2007 by Western policy makers and reporters to buy a detective novel set in North Korea and written by a former intelligence official and full of tantalizingly accurate details, such as the fact that North Korea had years ago built apartment blocks from East German blueprints.1 What we outsiders do find out is frequently mangled by misunderstanding. The difficulty with North Korea is both detail and interpretation.

In consequence, North Korea plays the outside world, intentionally or not, like a yo-yo. We get pulled in with expectation and cast out, time and time again. For example, relations warmed up in 2000, when South Korean President Kim Dae-jung visited the North Korean capital of Pyongyang for a historic first-ever summit. The country’s plutonium-based nuclear program had been mothballed for some time. Later the same year, U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright visited. Hopes for reconciliation were higher than ever before. But all along, the North Koreans were pursuing a new, uranium-based nuclear program. It was a matter of time before the world knew. After the program was exposed by the United States, tensions worsened and then, in early 2003, North Korea became the first country to withdraw from the international Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, the pact that prevents states other than the United States, China, Russia, Britain, and France from having nuclear weapons. With American troops having ousted the regime in Afghanistan and soon to be engaged in Iraq, Washington was looking at North Korea through a new lens, no longer as a Cold War “communist threat,” but as a potential ally of rogue states and terrorist groups. The War on Terror had come to Cold War Korea, bringing with it the likelihood of conflict.

Koreans are familiar with such highs and lows. Their country has long been a land of drama and extremes. Its rift into pro-Soviet North and pro-American South in 1945 was the most extreme among divided nations in modern history. Three million Koreans died when the two sides went to war. In the South, you will find Asia’s most fervent Christians. The North produced a communist personality cult that was—and remains—more fanatic even than Mao’s or Stalin’s. In the second decade of the twenty-first century, the North is still described as Stalinist. Exhausted by food shortages, it is economically shriveled. The rival South, meanwhile, is one of the world’s leading economies.

For all its bizarre fanaticism, North Korea was obscure until recently. After the 1950–1953 Korean War, it only occasionally poked out of its self-imposed isolation and grabbed attention. Each time, the reason was negative—assassination attempts on South Korean presidents; arrests of its diplomats for drug smuggling; training of terrorists; the seizure in 1968 of the USS Pueblo, a spy ship, and its crew; the axe killing of two American officers in the DMZ in 1976; the death of Kim Il-sung in 1994; famine; defectors. The only positive story I remember was when North Korea’s soccer players stunned the world by beating Italy to get into the quarter finals of the 1966 World Cup. The people of the English city of Middlesbrough, where they played their matches, became instant North Korea fans. The Koreans ran all around the pitch the entire match, a style that later became known as “total football.”

The country started to feature more in the world’s press in the late 1990s when its rogue nuclear program reached the desk of the president of the United States. Kim Jong-il is now sufficiently well known to be the butt of foreign talk show hosts and animators. This arrival was helped by a speechwriter’s afterthought. When the White House was preparing President George W. Bush’s 2002 State of the Union address, North Korea got slipped into the now-famous “Axis of Evil,” alongside Iraq and Iran, apparently at the last minute and possibly for reasons of style and political correctness, not policy.2 Somehow an axis of just two Muslim states didn’t seem complete. Many winced when they heard it, not because they didn’t think North Korea was evil, but because they knew it had no connection to Islamic terrorism, certainly not enough to warrant Axis of Evil membership. They thought this new label would ruin efforts underway in South Korea to coax it out of its hopeless isolation. The effect was to give this minor league rogue state a permanent spot on the U.S. presidential agenda.

Through all this, South Koreans and their friends have been able to reassure themselves that one day, at least, Kim will go the way of all flesh, and that change will come. In the fall of 2008, foreign governments were electrified by speculation that Kim was seriously ill, possibly incapacitated. Some speculated he had died. There was even a claim he had been dead for years.3 It transpired that he had had a stroke, from which he recovered.4 Then in 2010, the regime confirmed that Kim’s third son, Jong-un, was to be his heir. In contrast to his own slow motion grooming through the 1970s and 1980s before his assumption of power on his father’s death in 1994, Kim brought his son into the spotlight with astonishing rapidity. He was elevated from complete obscurity to four-star general and vice chairman of the Workers Party’s all-powerful Central Military Commission. This appointment could well mean more of the same for decades to come. There is no reason to assume the son of Kim Jong-il will be free to change course, any more than Kim Jong-il was able to shift away from the themes that characterized his father’s rule since 1948. That point was driven home in 2010 with two murderous attacks, one on a South Korean naval warship that killed 46 men, and the other on a South Korean island near the northern coast that killed four, followed by Pyongyang’s calls for peace talks.

Pool of Darkness

Compared to the normal flow of people and information between states, the country Kim leads is little known. It is unlit. Indeed, if you could scan northeast Asia from space every night—which the United States does, for obvious reasons—you’d pick up something odd. Amid the bright lights of China, South Korea, and Japan, North Korea is a pool of darkness. The black patch is home to 23 million people whose total available energy wouldn’t light up a single town across the border in South Korea. It’s not as if they can do without. The ocean’s giant fists have squeezed the Korean peninsula into mountain ridges, making four-fifths of it uninhabitable. It steams in midsummer and goes to 20 below in winter. You need air conditioning and central heating, as well as lights, to function. You also need fuel. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, as it’s called, is an industrialized state, mechanized and heavy industry–friendly in the communist fashion, when in better days heroines in hard hats posed for pictures with their tractors. It’s also right in the middle of a booming region that never sleeps, a three-hour flight from 40 cities with populations of more than 1 million. It should hum, but much of its population is in rags, literally living off grass, and struggling in heartbreaking misery. Why?

For answers, consider the spots of lesser gloom. Like, say, the energy-guzzling Kumsusan Memorial Palace on the edge of the capital, Pyongyang. This was once the country’s White House, where the Republic’s founding leader, Kim Il-sung, lived and worked and received visitors. After his death in 1994, Kim Jong-il, his son, who had other quarters in the capital, had the imposing granite edifice turned into a mausoleum. Elaborate equipment has been installed in this pyramid to sanitize visitors, as if they were entering a semiconductor plant. Visitors say there’s a section of revolving brushes that clean the soles of your shoes, a half-mile of moving walkways, X-ray machines, and sections where the dirt is air-blasted off your clothes. A marble corridor spits you out into a chamber featuring a white statue of the deceased Kim, illuminated from behind by pink lights. And, finally, you reach a vast, darkened hall, filled with somber music. Lit up in the center is a black bier where Kim Il-sung lies under glass in a black suit, brought to near-life by Russian embalmers.

The whole job, embalming and decoration, was lavish for a country with an annual trade of $5 billion, but what price devotion?5 Ordinary North Koreans often burst into tears when they catch sight of the corpse and don’t begrudge the cash, which anyway is too vast for them to conceive of. Their devotion is endless. It would be up to Kim himself to sit up and say, “This is embarrassing. . . shouldn’t you be at work?” This isn’t likely, not because he couldn’t come to life—he is the country’s official “Eternal President”—but because he got used to being needed in this way. In life, the senior Kim was referred to as the weedae-han suryong-nim, “Great Leader.” In his time, he was also variously referred to as—prepare yourself—“the Peerless Patriot,” the “Ever-Victorious Iron-Willed Brilliant Commander,” “the Sun of the Nation,” “the Sun of Mankind,” “the Red Sun of the Oppressed People,” and more. “He is the most famous man in the world,” a sincere student told me in Pyongyang. Not a shy fellow, Kim welcomed statues of himself in town squares, the biggest being the 20-meter-version bronze job painted in gold and unveiled on his sixtieth birthday in 1972. It overlooks Kim Il-sung Square, a short Jeep ride from Kim Il-sung University and Kim Il-sung Stadium. In the streets and fields, every adult citizen wears a badge bearing his likeness and, when they get home after a hard day’s listening to songs about him, they can gaze at his picture and that of Kim Jong-il that hang obligatorily in every home. There’s a revolutionary museum all about how he built the Workers’ Paradise. The country’s opera, theater, art, literature, and music are all about him. “I put forward the proposal of a 50-to-50 ratio between the creative works of the socialist construction and the revolutionary struggle,” he said in a guidance speech to writers.6 In other words, half of culture is to be about my activities as an independence fighter against Japan and half about my nation building. The Red Sun of the Oppressed People further “put forward the proposal” that literature should not be about the life stories of comrades who are still living and might become popular, but rather about comrades who sacrificed their lives—for him. So far, no North Korean has been short-listed for the Nobel Prize in Literature. A tower commemorating his version of communism stands a deliberate meter higher than the Washington Monument. It was built in 1982 with more than 22,000 white granite blocks, one each for the number of days he’d lived to date. Also finished that year was an Arch of Triumph, bigger and better than the one in Paris and marking the spot where he made a speech in liberated Korea after World War Two. The humble home where he was born is a tourist attraction, the other houses in the village long cleared away. Monuments dot the country where he or his family members allegedly performed a “brilliant exploit,” communist-speak for serving the cause. Everywhere he gave his world-famous “on-the-spot guidance,” there’s a commemorative plaque. Amazingly, he beat out the nonexistent competition to win the country’s top awards, the “Double Hero Gold Medal” and “Order of the National Banner, First Class,” and established his own to give out, the Kim Il-sung medal, the Kim Il-sung gold medal, and the Kim Il-sung youth award. His birthday, April 15, has been North Korea’s Christmas Day for decades. His face was more important than the country’s flag, the Song of General Kim Il-sung more important than the national anthem.7 It is, in short, the mother of all personality cults.

It’s tempting to argue that such lunacy derives from some withering insecurity. But Kim did not slip his own name onto the medal list or give quotas for statues of himself. One man couldn’t pull this off on his own. There’s a broader factor to consider. North Korea is indeed an aberration, but, as offensive as this may seem to southerners, the reverence for leaders demonstrated here is in keeping with Korean traditions. Visualize this: In January 2003, senior executives of Hyundai Asan, the affiliate of the South Korean conglomerate pursuing founder Chung Ju-yung’s dream of doing business in North Korea, went to Chung’s tomb to tell him they were opening the first road for tourists to travel into the North.8 The happy report was made at exactly 5:50 a.m., the bad-breath hour that workaholic Chung used to hold his regular morning meeting. This deference to a man who in life would kick his executives in the shins and throw ashtrays at them was entirely of their choosing. But it made sense, partly because their new boss was the most filial of Chung’s sons, but more because loyalty touches the Korean soul deeper than a balance sheet. In South Korea, freedom, sophistication, and competing loyalties serve to temper such cultishness. But in the North, it knows no bounds.

Who Is Charlie Chaplin?

In North Korea, we should consider an additional factor: ignorance. There are no other heroes because people don’t know about them and there is no negative news about the Kims to temper patriotic affection. Again, it requires some imagination to stand in a North Korean’s shoes and appreciate their media environment. What they don’t know about the modern world is astounding. On various visits, I searched in vain to find an ordinary North Korean who had heard of Elvis Presley, Michael Jackson, or, the most famous man of the twentieth century, Charlie Chaplin. Homo nordocoreanus has not been informed that man has landed on the moon because that knowledge risks making him admire America.

Also, importantly, he doesn’t know much about the objects of worship, the two Kims. He’s fed anecdotes and quotes, rather like Bible verses. Which raises an obvious comparison. The less one knows about a revered figure, the more difficult it is to strive to be like them and the greater the tendency to place them on a pedestal and worship them from afar. So it is with Kim Il-sung. Born of heroic lineage, conductor of miracles, single-handed liberator of Korea from Japanese occupation, he is placed so impossibly high that all the subject can do is believe, worship, and proselytize. The call to express loyalty is louder than the call to be like him and nation-build, which may explain why North Korea is an economic basket case. Furthermore, there are no alternative heroes. No movie stars—North Korean films do not even have credits—rock artists, writers, politicians, TV personalities, athletes. And, importantly, no ordinary heroes like firemen, cops, guys rowing across the Pacific, no ascents of Everest, no kids with cancer. Only Him. At school, children learn of His exploits and His love. Of how the Americans started the Korean War and He repelled them. No one tells them that He started it. The elderly know but they keep quiet. Everyone memorizes sections of His Thought. Even prisoners. At train stations, hymns about Him waft from loudspeakers, insinuating their way into the homesick traveler’s emotions. Unity around Him makes us a world power, they think. One day He will free the poor children of South Korea. And when they take the otherworldly journey through His former palace till finally He is lying there before them, they feel unworthy. O magnificent protector. The suffering of the nation bursts and they bow sobbing. It’s religion.

In a democratic world, dictators must justify themselves. They link to their people through shared values, ideas, and attitudes that the smart ones codify for study. To suit his posture as the first Korean leader to break from the long tradition of dependence on foreign power, Kim Il-sung needed his own system of thought. It is called—what else?—Kimilsung-joo-eui (Kimilsungism), but is better understood by its official name of Juche, which means self-reliance. It made Kim seem like an international leader and gave the people something homegrown to study. But citizen and leader in North Korea have always been bound by a subtext that only gets fully expressed in Korean language for domestic consumption. This is a race-based message of Korean superiority, not the born-to-rule superiority the Nazis and the Japanese used to justify their conquest of inferiors, but a more subtle we-are-so-pure-and-innocent-that-we-need-a-great-leader-to-protect-us. It justifies the Kims’ rule and explains away what, for communists and even true believers in self-reliance, are its blatant failures. This racist message sustains even today, despite the superiority of South Korea in all measures, the delusion that all Koreans will one day see the Kimilsungist light.9 If this is the pen in the hand of Kim Jong-il’s rule, it needs the hammer in the other. That is, the fearful repression that keeps the citizens in line. We shall return to both issues in later chapters. But for now we should note the most significant factor behind the cult of the man lying in the mausoleum in Pyongyang: the role of his son in its creation.

Koreans historically are known for fervor. Before producing the world’s most fanatical and rigid communist cult, they had adopted Chinese Confucianism and its core value of filial piety in the most extreme form. South Korea boasts Asia’s most devoted Christians and, if such a statistic could ever be measured, we’d probably find more heretic spin-offs and start-ups per head than anywhere else in the world. This curious energy seems to come from what we might call the shaman within the Korean psyche. Before Christianity, Confucianism, or Buddhism, shaman-kings ruled Korean tribes. Their legacy remains in the Korean makeup. The shamans did not teach about contradictions such as good and evil, and right and wrong, which tend to make people pause and think about their feelings and actions. They saw the individual as a whole, men and women as being of equal value, and each person’s characteristics as equally valid. This I’m-okay-you’re-okay approach provided the confidence to implement another shaman idea. That is that life should be lived to the full. To be truly human, you must act with all your energies.10

The involvement of Kim Jong-il acting with all his energies provided the vital catalyst that made the cult of Kim Il-sung the most extreme in the communist world. In the early 1970s, Kim Jong-il controlled the “4.15 Creation Group,” named after his father’s birthday, which produced the immortal classics which the public was led to believe flowed directly from the Great Leader’s own pen.11 Kim Jong-il oversaw the building of the Juche Tower, the Arch of Triumph, and the Kim Il-sung Stadium for his father’s seventieth birthday.12 This was how the son demonstrated to his father and the old revolutionaries around him that he was devoted to their cause and a worthy successor. It was also the means by which he was portrayed to the citizens as a nice, cuddly fellow, whose filial devotion was greater than theirs. This was how he became known as the “Dear Leader” (chinae-haneun jidoja).

Teaching Journalists

For outsiders, the Dear Leader title is laughable. Indeed, it is hard for us to believe that the hand that writes such flaky propaganda belongs to one of the world’s most ferocious regimes. For so much of it has the character of a fairy tale with the Dear Leader touching the small stuff of life with his magic wand. For example, back in 1965, the Dear Leader—who, according to the book The Great Teacher of Journalists: Kim Jong-il, always sees everything “with an innovator’s eye and (grasps) the developing reality and the aspirations of our people”—changed a radio signature tune. On his return from a “long trip to a far-off country, the dear leader came to inspect the Radio and TV Broadcasting Committee, without even stopping to break the longstanding fatigue of the journey abroad,” and said:

The character of our radio tune now in use is dull.

Our broadcast is the voice of our Party which is guided by the leader, the voice of Juche Korea. So the signature tune which identifies the beginning of our radio programmes (sic: British spelling in North Korea) must naturally be a melody associated with the leader.

It would be advisable to adopt as signature tune the melody of Song of General Kim Il Sung, the immortal revolutionary hymn which is sung with feelings of high respect for him not only by our people but all the people throughout the world.13

As foreigners, we can only ever peer in at North Korea and try to make sense of it. I’d be the first to admit, though, that it is easy to misread what it’s all about. Indeed, Westerners misread the country all the time. I saw a couple of embarrassing displays of this the only time I was at Kumsusan. It was for Kim Il-sung’s eighty-second birthday in 1994. By that time, international communism having collapsed, the foreign turnout was so poor that the delegation I was in, which included a former premier of Egypt and a former governor-general of Canada, provided the festivities’ main VIPs and got invited to lunch. This group also included representatives from CNN, the Japanese TV network NHK, and three from The Washington Times, which I was writing for at the time. When the 20 or so members lined up to shake the Hand, the reporter in me decided to stand instead near Kim and take pictures. I was close enough to catch the brief exchange with each guest. One, an American academic, had met Kim once before and obviously thought they were friends. When it was his turn, he leaned back dramatically, spread his arms wide, leaving the proffered Hand hanging there for a moment, and exclaimed, “You look great!” Kim Il-sung maintained his gracious composure, but I swear a shadow flitted across his eyes as he tried to place the man. Not only did this Washington-like familiarity seem off the mark, but so was the observation about his health, for two months later Kim was dead. The penultimate figure in the greeting line was the Korean-American consultant who had arranged the trip. Kim knew her, considered her a “foreigner,” and so welcomed her with a smile. The Hand then went out for the last person. When he saw who it was—the lady’s North Korean business partner—the Hand dropped and the Great Leader turned away with a scowl, leaving the hapless fellow to ponder his faux pas.14