Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

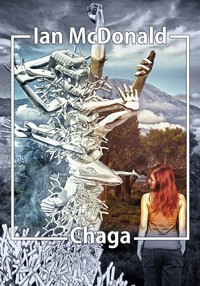

- Herausgeber: JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Chaga

- Sprache: Englisch

The end of the universe happened at around ten o'clock at night on 22 December, 2032. It's just that humanity hasn't realized it yet. And the Chaga, the strange flora deposited from the stars, is still busy terraforming the tropics into someone else's terra. Gaby McAslan was once a hungry news reporter who compromised her relationship with UNECTA researcher Dr. Shepard for the sake of her story... but Gaby is no longer a journalist and she doesn't want to be a full-time mother, even though her child Serena is her last link with Shepard. Gaby's fire has gone out; she's gone soft. But the massive political and military upheavals rocking the world are about to drag her back into the action. REVIEWS "This is a huge and ambitious novel, the work of a supremely talented writer approaching the top of his game." – SFX "So outstanding a writer that he deserves reading beyond the science-fantasy market ... He has such marvellous talent, so vivid an imagination. His prose sings and zings – simultaneously." – The Times

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 716

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Kirinya

Copyright © Ian McDonald 1998All rights reserved

The right of Ian McDonald to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published as an ebook in 2013 by Jabberwocky Literary Agency, Inc., in association with the Zeno Agency LTD.

Cover design by Dirk Berger.

ISBN 978-1-625670-71-7

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

New Moon in Saturn

The Crossing

Fragile

AK47 Hour

Freedom Tree

About the Author

Also by Ian McDonald

‘The tree of man was never quiet’

A. E. Housman

A Shropshire Lad: XXXI

New Moon in Saturn

1

The dark was almost gone now. Morning clung to the horizon, a line of amber on ocean edge. As the woman watched, the line deepened, revealing interlaced fingers of cloud, darker on dark. Weather systems were moving far from land; ripples of indigo cloud spun out from the slow, vast spiral of the monsoon. The beach was a plane of sound; surf ponderous on the reef, running high on the fringe of the healing rains; pipe and flute of beach birds lighting and running a few quizzing steps and lifting again as easily as thought; the language of the breeze off the sea in the revenant palms and the tall, slim spires of the land corals. The music from the party ebbed and ran, now soft, now thudding.

In the place between the sown and the sand, the woman stopped and, lightly, fearfully, touched her hands to the baby slung between her breasts.

‘Listen,’ the woman said.

Impossible that the child should understand her, yet in the gaining light she saw her daughter fold up her face and fists to squeal; then relax, fall silent and still. In the same instant the wind from the ocean caught the music and blew it back in through the door of the bar. The woman and the child stood enfolded in presence. The moment stretched, the moment snapped.

‘Nothing,’ the woman said. She smiled for herself. ‘You’ll learn.’

She went on to the sand. There was light enough to make out the shapes of the scuttling crabs – but not enough to avoid them. They burst under her boots in crisp, kicking thrashes. The small white beach birds came sliding off the ocean wind to pick and tear at the agonized footprints.

‘Look, there goes Mr Crab!’ she told her daughter, who was now frowning because it felt good. ‘And here comes Master Crab; will we get him? Yes!’

The baby gulped air. The birds lifted and settled to rip and heave with their orange beaks.

‘Whoa Mrs Crabby!’ the woman said, running fast after the big mother of a hen crab, as fast as a woman with a baby at her breasts may run in soft, tide-wet sand. Mrs Crabby hid herself beneath the lap of tide foam.

All but the brightest stars of the southern hemisphere had faded. The moon was still up, a day past new; the crescent moon of Africa, lying on its back, cradled by the open palms of the hand-trees. The moon held a star between its horns. The woman knew that a pair of binoculars could open up that big, soft star. It was a cylinder, passing through the same phases and occultations as the true moon. It was an artefact, a hollow world three hundred kilometres long, one hundred and fifty across its faces. It hung midway between earth and moon. Such truth put a catch in the breath and needle of cold in the sense of mystery.

‘Hey,’ Gaby McAslan said to the baby, who happened to have tilted her head back and turned her face to the moons. ‘Wave a fist to Daddy.’

The anger was so sudden, so acid and smoking that she was paralysed for a moment. Crabs hurried around her feet. Only a moment: she walked on. Tidewater seeped out of the sand into her boot prints.

Second moon in the arms of the first. An auspice: a time of journeys undertaken, endeavours embarked upon, courses changed, lives turned to a different wind. Astrology was among the least of human activities to have been transformed by the advent of the BDO.

They should rename it, Gaby thought. It’s Big, it’s undoubtedly an Object, but it is no longer Dumb. We just do not know what it is saying to us.

‘Born with the BDO in Cancer,’ Gaby whispered to her daughter. ‘A journey begun. Death and rebirth.’

Saturn and the new mysteries unfolding among its satellites were below the western horizon. They would be partying with one eye on the monitors at the Mermaid Café. Gaby hoped she would not have to be there to see whatever happened out there. Her life had been tied to those far, cold moons by forces more subtle and powerful than astrology. Twelve years ago it had been a different shore, a different continent. Ireland. The Watchhouse. The Point. Home. A different person: the kid that had wished on a star and become Gaby McAslan, SkyNet television journalist. Gaby McAslan, exile. A different moon: Iapetus. She had gone out on to the Point that evening to be caressed by mystery, to be impregnated with sign and seal. From twelve years up with her child in her arms, she could look back at that gangly kid and see that she was not looking for a true sign, for that could have as easily pointed away from as to her heart’s desire. She had looked only for confirmation of what was already certain. Iapetus had turned black; then Hyperion had vanished in a flash of energy, but it was decided somewhere surer than in the stars that she would become a network journalist.

‘The older you get the more you learn, the more you learn the less certain you are, bub,’ she told her daughter. Twelve years higher, might she look down astonished at the self-assurance of this thirty-year-old?

The upper limb of the sun was fountaining light out of the sea into the undersides of the clouds; staining them purple, crimson, black. The headland was still in shadow but highlights and glints lit Gaby’s track up through the fan-cover. She went more cautiously than the gentle climb deserved. She feared slipping and crushing the baby. The way was well trodden; the headland was a popular viewpoint for the people of Turangalila. You could see twenty kays up and down the reef. On the clearest of days you could make out the great breaches where the ships had passed through into the port of Mombasa. Now the only ships on the sea were the low, grey hulls of the quarantine fleet, pressed low on the horizon, afraid of infection. But the news from down the coast was of a great, vibrant culture growing from the stumps of dead Mombasa. The infection the quarantine ships feared was a disease of nations. It had killed Kenya, it was killing Tanzania by the minute, but the people of this coast were Africans before they were people of any nation. They were as fecund and inventive as the slow-breaking wave of alien life that was transforming their land, fifty metres every day.

But Mombasa is gone, Gaby thought. The Mombasa I knew in those final, frantic days of the nation formerly known as Kenya. I loved that nation, I loved that land, and the Chaga took it apart. I loved a man there, far away, and it took him. Everything I loved has been taken by the Chaga: the place I drew power from, the people I loved and tormented, the ambitions and abilities that defined me.

She paused on a steeper section of the slope.

‘Woo. Still haven’t got over having you, bub.’

Her daughter blinked at the sky. Tiny, tiny red living thing. Gaby continued up the path. The sun continued up the sky.

‘You knocked me right out of condition, you know? If I’m going to play in the Kanamai game, I have to get back into serious training. Do some running, bit of swimming.’ She paused again, out of breath.

The spine of the headland was thickly wooded in a mixture of alien and reconstructed terrestrial vegetation, but at the very tip it opened into a sun-burned nose of bare earth. Here Gaby set down the leather bag. She took her daughter to the edge. The headland tumbled in laps of coral rock to a low shelf where the sea ran dangerously. Over her shoulder the moons set; their brief conjunction broken.

Good, Gaby thought. I do not want you with your eyes full of moon. I do not want another life tied to the powers in the sky.

Gaby unlaced the papoose. Her two hands held her daughter up to the light.

‘Serena,’ she said, blocking out the sun with her child.

Gaby hesitated. She needed to say something elemental, but the growing light of day embarrassed her little ritual. ‘You are my Serena,’ she said weakly. The baby kicked in her hands and she looked at her and suddenly saw that it would be the easiest thing in the world to open those hands. To let her fall. To let the waves slide the thing off the coral platform into the sea.

Serena kicked again. Gaby shook her daughter.

‘You bitch!’ she shouted. ‘You little bitch! Do you know what you’ve done to me?’

Serena began to cry.

‘Shut up, shut up, just shut up you little, fucking, bitch!’ Gaby shook Serena to the rhythm of her rage but she could not shake silence into the baby. Serena screamed.

‘It’s because of you I’m here, because of you I can’t go back, because of you they won’t let me out. All. Because. Of. You.’

Do it. Be free. She’s not perfect. She’s not true. There are still tribes that expose the ones it touches and changes. Just open your hands. A fumble, a slip. It could happen. It would be dreadful, but only for a time. She’s not perfect.

Gaby felt her hands tremble. Light filled her eyes. With a cry she snatched the baby girl out of the sun and pressed her close, enfolded her in her long, mahogany hair.

‘Oh my wee thing, my wee thing; oh Jesus oh God, I’m sorry, I’m sorry, my wee thing.’ She sank to the earth, rocked the screaming red blob, terrified by what the light had lit up within her. ‘Oh Jesus, bub, oh Christ, I’m sorry, I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I’m sorry. What was I thinking?’

She remembered what she was thinking.

When the Chaga fell from the stars to spread across half the planet, it had changed more than geography. No one had ever seen the intelligence that had conceived and constructed the biological packages that had fallen for fifteen years – it was accepted now that the Chaga-makers were unrecognizable and unintelligible to human chauvinisms on life and intelligence – but their intentions could be surmised. Not conquest, not colonization – though the Chaga, converting all in its path to its matrix, was a particularly voracious imperialism – but discourse in the only way the Makers understood; through mutual evolution. Earth’s southern hemisphere was a voice in a dialogue that crossed eight hundred light years and five hundred million years to the complex fullerene clouds in the Scorpius loop. The Makers wrote their dialectics in human DNA.

Changed.

There was an irony to this.

In that other life, when she had been Gaby McAslan, East African Correspondent for SkyNet Satellite News, she had exposed that truth to the planet. Still a shudder when she thought of Unit 12, and what the United Nations had tried to hide in its labyrinth of levels and chambers. She had only escaped because friends in powerful places had pulled for her.

Thanks, Shepard, she thought at the place where the BDO had set. And I treated you like Satan’s shit. But I do that. That’s the way I am. And where were you the next time I ran up against the UN quarantine force and its long memory for grudges? You probably don’t even know what happened, up there in that big tin can. You probably don’t even know you have a daughter named Serena. You certainly will never know what they said about her, when they brought me out of decontam that time, when there was no one there, and they showed me the results of the tests and stamped the papers and gave me over to the troops.

Exiled.

They could not, or would not, say what the nature of the change would be. Only that the cluster of rapidly dividing cells in Gaby’s womb would be a girl, and it had been touched by the alien.

Gaby closed her eyes as she touched her lips to the crown of Serena’s soft skull.

‘I’m sorry, I’m so sorry, my wee thing.’

She hooked Serena into the sling. Breast-warmth and heart-rhythm soothed her screams. Gaby unfastened the unitool. A twist of the shaft locked it into a short shovel. She dug until she hit cliff rock. She hoped the scrape would be deep enough to discourage scavengers.

The leather satchel had not leaked. There were still a few soft ice crystals on the afterbirth’s liver-dark surface. Such an alien thing to keep inside you. Beautiful and repulsive, like something Chaga-grown. But she did not tip it into the hole, not yet. That would be to give part of herself to the land. She had always drawn her power from the land: her childhood expeditions to the hidden places of the Point; the wide places of Kenya, before the Chaga swept across them, now this promontory overlooking the sea. You gave yourself to the land and it let you put your roots down into it and suck its power and become definite. It made you a person. But she did not know if she wanted to be the person Turangalila would make her. To bury the afterbirth would be to bury Gaby McAslan. She was afraid she would not recognize the life that was reborn.

‘Give me a sign,’ she said. The sun stood three fingers above the ocean. Light filled up the land, casting new shadows and definitions with every second. The deep water was restless, all glitter and urgencies; the reef like knuckles of earth pulling back from the dissolving sea. The air was clean and cool and smelled of the big deep. That had always been the most evocative of smells to Gaby; restless and yearning. The elements were strong here, but they had no sign to give her.

The tide was high after moonset, lapping under the sagging shore palms. Turangalila’s boats were beached high. Turangalila itself, blended with the canopy of pseudo-fungus and land corals, gave no indication of human presence on this coast. In the early gold the Chaga-growth and the coconut palms and occasional baobabs did not seem mutually hostile, but symbiotic products of an alternative evolution track, taken back in the pre-Cambrian.

Not such a fanciful notion, if the theories were true that this was merely the latest in a series of interventions in terrestrial evolution by the Chaga-makers.

The tide and the trees and boats hugging them and the settlement folded into them had no sign for Gaby McAslan.

She turned inland, to Africa, to the place where the ragged carpet of the coastal ecology lifted and tore into the stunning uplift of the Great Wall. There trees, or things that seemed like trees, rose sheer for a kilometre and a half before unfolding into a canopy of immense interlocking hexagons. The roof of the world. From here you could see that the Great Wall curved gradually inland to north and south. The formation was a curtain wall one hundred and fifty kilometres across. It occupied the whole of what had once been East Tsavo game reserve.

Beyond the Great Wall you could not see. From experience she knew that it contained many landscapes and ecosystems nested like babushka dolls. But it was changing, adapting, moving towards humanity as humanity moved towards it. It was the evolutionary dialogue: the reconstructed palms, the neo-baobabs, the Chaga plants that were drifting towards terrestrial species, the animals that were creeping back through the coastal forests exploiting new ecological niches: symbiosis. Growing together.

The trees and the Great Wall and the landscapes hidden behind it and the creeping animals of the coast had no sign for Gaby McAslan.

Serena’s fingers seized and tugged a coil of her hair.

‘Ah! Shit!’ Gaby said, and understood, and laughed, and tipped the quivering blood thing into the hole and quickly covered it with earth.

As Gaby went carefully back down the path to the beach she sang her daughter Motown soul classics that were old before Gaby had been born. The beach crabs were all down under the high water. The white birds that had pecked at the bloody footprints rested on the surface, top-heavy, as if the next gust might capsize them. The ribbons of dawn cloud had broken up into soft black beads, moving fast inshore under a strong wind running at a thousand metres. There would be rain on the coast before noon.

Gaby clambered over the slumped palm trunks, splashed through the sea-run around the thick red wrists of the hand-trees. She heard Hussein’s radio before she saw him at his boat, pulled up under the wall of the dead hotel. He was tuned to one of the new stations beaming out of Malindi. It played morning music, bright, intricate guitar sounds and funk-Swahili DJ-babble. Hussein was scraping polyps from his hull. He liked his boat smooth and straight and lean and long. He was a tall, hairless Giriama with a streak of mission-widow Masai, and a devout Moslem in the way that all men who go on the sea are devout. They respect God, but not religion.

‘Gaby. And Gaby’s child.’ He spoke hotel-English and hotel-German. Before the hotels were swept away he had run glass-bottom boats and snorkel tours to the reef. ‘You know, my uncle’s people used to fry it with onions and curry spices and eat it in chapattis.’

‘That,’ Gaby McAslan said, ‘is disgusting. Is the Mermaid still open?’

‘There was noise coming out of it when I went past half an hour ago.’

‘You don’t know if the Phoebe thing has happened yet?’

‘Gaby, I sail boats.’

‘Yeah, yeah. You’re taking her out today?’

‘Every day there are wetbacks and raft people want to come here, I go out.’

And they will have brought small handfuls of their treasures with them and you will ask for a something here, a something there, a token or favour to be repaid sometime never, Gaby thought. Not because you need these things – no one needs anything any more, but because freedom has a price. As if they have not already paid it to the freighter captains that put them over the side outside radar range, and pay again as they paddle and kick and swim past the blockade ships, and pay the sharks and the Portuguese men-o’-war, and pay the waves and the reef as they try to make it over into the lagoon. But they have not paid you.

‘You are a God-damn pirate, Hussein,’ Gaby said amicably.

‘I like to think of myself as an immigration service. An underground railroad in the ocean.’

‘I think the word is submarine,’ Gaby said. Hussein fed syrup to the putti-putti. The biomotor burped and began to beat, pumping air. He adjusted the pulse, then disconnected the cell battery. ‘But you be careful, right?’ Gaby continued. ‘One of these days those bastards are going to blow you right out of the water.’

‘I am Captain Stealth, I sail under their guns and they cannot see me.’

‘You put too much trust in that radar-transparent hull of yours. They may be Saudis, but they have eyes in their heads.’

‘God’s will, Gaby and Gaby’s child.’

‘Serena.’

‘Ah. That is a good name for this country.’

‘God’s will, Hussein.’

Yes, Gaby thought as she went up the path that had once taken tourists to the beach and the glass-bottomed boats. That is why you laughed on the headland when Serena gave you the sign you had not been expecting. God pulling your hair, hey, listen, after all those years of wanting and trying, you are an African. A white-skinned, green-eyed, red-haired African. And what makes you African is that you finally accept My will, whether you stay or go, whether you drop your baby from the cliff or bury your afterbirth in the earth. This is the world you have to live in, now, here. Ismillah. So laugh, because there is nothing you can do about it.

The path was not the most direct way to the Mermaid Café but the Chaga kept rearranging the shortcuts and the crumbled ruins of the hotel were treacherous. The empty swimming pool waited in there somewhere; a blue tiled pit trap. Gaby stepped through the place where the chain link fence had fallen under the weight of sulphur-yellow moulds into the tennis courts. The far service area had been colonized by bulbous blue and white growths like over-sized Chinese vases that exuded a strangely alluring musk. Clusters of minute orange crystals infecting the tramlines crunched like crab shells beneath Gaby’s boots.

The carved mermaid was nailed to a palm behind the pile of scabrous machinery that had once chlorinated the pool. She had a sluttish leer and pointed along a track that meandered between palms and crown corals. The Mermaid Café was one of those unawares buildings that you are at before you realize. When you learned the trick of picking it out of the visual chaos of vegetation, what you saw was something ludicrously like an enormous straw sombrero propped up on short stilts. It was very much more alien and clever than that: its thatch was a fine solar fur that cooled the building in the heat of the day, warmed it by night, and generated electrical current in every fibre. When you ducked under the brim and your eyes adjusted to the bioluminescent shade that is best for contemplative drinking you saw that it was more like a tree than a hat, for a thick central trunk held up the roof. Branch-ribs ran down to the brim and became the strong, bone-like stilts. Tree-hat-hut.

The Mermaid Café smelled of warmth and things growing from deep soil, sweat and the urinous hum of spilled beer. Most of the tables were still full. There were some seats at the bar that circled the trunk. The main biolumes clinging under the canopy were dull; the bar was lit by table lamps and television. The screens hanging from the central trunk were all full of stars.

‘Gab!’

Sunpig was a short podgy white American woman of middle years. She wore more than one ring on each finger. Illustrated cards lay in various patterns across her table. They bore the wide eyes, seraphic faces and blessing hands of Ethiopic icons. Sunpig’s work at Turangalila was to develop an uniquely Cha-African tarot. Everyone at Turangalila had a work; that was the dream of the place, the expression of the transforming potential of the Chaga into every field of human activity. Like most experimental artistic communities, these expressions tended to end up in the bar.

‘I did it.’

‘And?’

‘There’s an “and”?’

‘Woman with child!’ With a flick of his forefinger, Dr Scullabus directed his patrons to make way for Gaby. ‘Sit.’ She sat. ‘Drink.’ She drank the house beer set in front of her. The Doctor was tall, with bad skin but good jaw-length bleached dreads. Gaby liked Dr Scullabus hugely. He was that age when men like to give themselves names, but he had her respect. He had used the Chaga to remake himself. Before it came sweeping down the coast from the impact at Kilifi he had been a beach boy. He had worn good muscles, lycra shorts, no body hair, and fucked tourists and let them spend their money on him. When the tourists stopped coming, he fucked journalists and UN workers instead. He had never had any money so he lost nothing when the Chaga took the hotels away. His skills at getting what he wanted from people it could not change; they had earned him the Mermaid Café and his place behind the bar as supreme pontiff.

Gaby lay Serena on the bar. She blinked at the star-filled screens. It was hot under the sombrero; Gaby’s shorts and vest stuck to her. But the beer was cold. She drank it down in one go. The Doctor brewed it himself but the bottles were many many times recycled, scavenged from the overgrown trash heaps of the lost hotels of his youth.

‘You missed it, Gab.’

‘Was it cosmic?’

‘The man on the satellite news did not have any idea what he was talking about. You would have done it right, Gaby. You would have made us feel the size of the thing, and the bigness of space, and how far away it is, and how cold, and how wonderful.’

‘Doc, it’s no wonder you got so many rides.’

‘It is true, Gaby. If you had been there, I am telling you, you would have given us such big awe that it would have made our balls go tight.’

‘But I’m not.’ Gaby rolled the much-washed beer bottle between her palms. ‘I’m here. And this is another one on my endless account.’

Chaga-nomics. Quid pro quo: with Andre the Doctor would trade beer for a day’s fishing beyond the reef; for a song from Harrison, for a reading from Sunpig, for a dinner from Marilynne, for a restyle of those dreads from Musta. But from Gaby McAslan, former SkyNet East Africa Correspondent, what has she to sell?

Gaby banged the empty bottle on the bar. Serena gave a small gurgle but thought sleep better. New beer was delivered. Gaby drank it down. Breakfast of champions.

Those amputees who suffered phantom pains in lost limbs, how long before the twinges faded? Ever?

She looked at the screens. Since the dark side of Iapetus had engulfed the bright and Hyperion had vanished, heralding the advent of the Chaga, a steady stream of space probes had been sent to Saturn’s moons. The arrival of the Big Dumb Object, reconstituted from the fragments of Hyperion, in Earth orbit, had eclipsed the unmanned missions – why go to Saturn when Saturn has come to you? Then Phoebe had disappeared in a quantum black hole explosion, and the powers in the sky were moving again. Saturn satellite mission twenty-two, Wagner, had been retasked for a ring-side seat to whatever the Chaga-makers had willed for Phoebe.

It had arrived in the Phoebe Rift, two days after Serena’s birth. It had unfolded its antennae, uncoiled its sensor booms like a luna moth hatching and seen slender arcs tens of kilometres long tumbling slowly in trans-lunar space. At three thirty-five GMT the will of the Chaga-makers had become manifest: the arcs joined. The processed images from the orbital telescopes had sketched a ring three and half thousand kilometres in diameter.

They had a name for this one too. The arcs had not even joined and they were calling it Éa. Enigmatic Artefact.

One minute to fly-by. Wagner would pass through the ring within one hundred kilometres of the inner surface. The terrestrial long-baseline interferometers could resolve with greater discrimination than the space telescopes: Éa was a thread, a hoop two kilometres wide by five hundred metres deep. Wagner would have to look hard to see anything.

Expert voices were opining that Éa did not account for all Phoebe’s mass.

And suddenly there it was, swimming out of the dark as it caught the distant sun, like a bracelet of light. Somewhere, Gaby was aware that Serena was hungry. She slipped a tit out of her loose vest and picked up the grizzling child. Wagner swept through the hoop of light like a weasel through a wedding ring. Gaby glimpsed coiling white ridges, like twined intestines, valleys between bristling with stiff quills. Then stars. Wagner brought its rear camera booms to bear.

Every screen in the Mermaid Café went white.

‘Hey, Scullabus!’ someone shouted from the far side of the bar.

‘My televisions are fine,’ the Doctor said. ‘Look.’

The probe cameras had pulled out and stopped down. Éa was a disc of white light. The dazzling screens threw unfamiliar shadows into the recesses of the Mermaid Café. Darkness. Where the light had been, precisely framed by the huge ring, was a moon.

Many of the Doctor’s bottles that were more precious than what he sold in them hit the floor and shattered.

Not even the expert voices knew what to say.

The moon was a monster: rust-red, cratered and rayed. Dark mares were cracked and faulted like Japanese glaze. The satellite had a satellite. Hovering beyond the new moon’s Roche limit was a curved disc eight hundred kilometres in diameter. Its radius curvature matched the moon: its dark side trailed floes and stalactites of frozen gas tens of kilometres long. Gaby found it impossible to resist the notion that the disc was pushing the moon.

Like its predecessor, this even bigger, dumber object was inbound. Simulations drew curves on the solar system. Its destination was not Earth. In twelve years’ Venus would have a moon, orbiting every twenty days.

Gaby grimaced; Serena was gumming hard. She probably needs winding, Gaby thought. The incongruity of that thought with the wonder stuff on the screens almost made her laugh aloud. All it was was one dead rock going to another, but this was a human child. That was mechanics. This was the future.

What a universe you’re going to grow up in, kid.

The Crossing

2

Her name was Oksana Mikhailovna Telyanina. She had flown with the wild geese and swum with the salmon. She had run with the reindeer and stolen the eggs of eagles with the ermine. She had travelled on the wings of the wind and entered the spirits of the trees. She had become light, and the light beyond light that was the true illumination, of which all light was a shadow. She had dissolved into the waters like a drop of rain, she had been the blade of grass crushed by the hoof of the deer, and that deer that crushed it. And now all that remained were wisps of chemical ash in her bloodstream and she was a fortysomething woman sitting in an oak tree. Bare-ass naked with the first frosts only days away. Nippled with goose-flesh, but the tits were still firm, by God. A tight forty something woman. Keeping in shape was an element of the greater spiritual exercise.

But you are cold and stiff and vertiginous from the mushrooms. And feeling old.

And unanswered. Two days until she flew south again, back to Africa, and her spirit was still unquiet.

‘Tell me,’ she had said to the wild geese and the salmon swimming upstream to death. ‘What should I do?’ she had asked the reindeer and the ermine. ‘Is this right?’ she had questioned the wind and the trees. ‘Are you listening?’ she had asked the light and the water. ‘Is there anyone there?’ she said to the grass and the deer that trampled it. The geese and the salmon and the reindeer and the ermine and the wind and the trees and light and the water and the grass and the deer had answered fuck all.

It did not work any more. The spirit worlds were closed to her. She might as well have skulled-out on her living room carpet and read divinity into the swirling patterns of the Turkmenistani weavers. She would not have risked pneumonia and fractures from falling, stoned, out of a sacred oak.

The sky read imminent evening. She had been beyond for eight hours. Once she would have walked the branches of the world-tree for days on that much skag. It is a bad sign when it takes more and more to do less and less, she thought as she clambered down the steps cut in the trunk. She dressed quickly, bouncing up and down to shake heat into her body. There was chocolate in the backpack, and the hip flask with the last of the arak. She swigged from the flask as she took the shaman-path through the deepening twilit woods to the logging road. The stuff burned brave. For the first time she felt need of its reassurance. The spirits had closed their hands and eyes. Their protection was no longer assured. She unbuckled the strap on her bush-knife. The things that lived and killed in the dark were afoot, calling. She was glad to see the rusty Cossack 4×4 in the pull-in off the rutted road. Her hand lingered on the reindeer antlers fixed to the bull-bars. Once, an emblem of her uniqueness: look, here comes Oksana Telyanina, shamanka, now they were as embarrassing as an old school backpack covered in the names of pretty-boy bands. Fortysomething and you are still a teenager, Oksana Telyanina. You are on the downslope of your life and you still need these emblems and totems to tell you who you are.

She fished the magnet out of the glove box and pressed it to the scarred mound on her wrist. The diffusion pump control was tricky; confirmation of success was the purr of the processor as it leached the lingering traces of the trance drugs and arak out of her blood. Molecule by molecule it exposed the hollow in her life. It was many-lobed, branching like a meltwater lake on tundra.

The slot of sky filling the narrow cut of the logging road grew dark. The autumn stars appeared, a great wheel turning above the Siberian taiga. Venus seemed to hover at the road’s vanishing point: guide star into night.

It was an hour back to the highway, another two hours home.

Stone cold and sober, Oksana turned the ignition.

Venus exploded: a white flare, hard and brilliant enough to cast the shadow of the steering wheel across Oksana’s belly. She cried out with fear. She had destroyed a planet. Her power had run wild; the stars were falling through the twenty-seven heavens. The spirits in the forest would rise up and rend her soul for this. She flicked on the headlights; her wheels chewed dirt. The battered Cossack slewed on the needle-strewn surface. Eyes in the dark threw her headlight beams back at her.

Oksana floored the brakes. The 4×4 shuddered to a stop, antlers a rip of velvet from the trunk of a big larch.

On a dirt road in the middle of forty thousand square kilometres of wilderness, Oksana Mikhailovna Telyanina laughed hard at her presumption. The stars were not falling. She had seen two hundred billion tons of cometary ice enter Venus’ atmosphere at one hundred kilometres per second and convert its mass into plasma.

She banged her hands on the wheel with delight. She understood why the spirits had been silent. They had long memories, in this triangle of land between the Stony and White Tungus rivers. They had felt the hammer of God fall. And that had been a few megatons, a few hundred square kilometres of felled trees, pointing j’accuse at the epicentre. The mother that hit Venus had another fifteen hundred sisters behind her. The scientific assessments appalled Oksana’s shamanka spirit. The momentum transfer from the impacts – each enough to scour Earth as sterile as a gynaecological tool – would speed up the planet’s rotation. The new dawn would break every forty-two hours, and a new moon would sail its nights.

Tectonics and carbon cycles: each impact blasted a hefty megatonnage of the planet’s massive atmosphere into space. Tidal forces kept the inner fires burning, like Jupiter’s sadomasochistic relationship with tormented, cracked Io, or Earth’s moon with its mother mass.

Life, ultimately. That was what Oksana understood of the Chaga-makers. That was what she had seen in her years flying for the UN in the mutating Africa south of the equator: life exploding in a million new songs and dances. Big life. Great life. Before each spring must come a winter, be it the winter of ice or the winter of plasma fire. Or, she thought, hitting the radio tuner buttons at random until they settled on a pirate country and western station; ice and fire.

The new moon’s companion object, the huge disc nicknamed Moondozer, had cast off when the red satellite was adjusted into its final orbit. Its course was a long, narrow loop that would return it to Venus in eighteen months in an orbit a scant one hundred kilometres above the cloud tops, ploughing through the nebula of ionized atmosphere. The theory was that Moondozer would use this gas ring as a seed bed to crash-cultivate fullerenes. For three hundred years a rain of Chaga-spores would fall upon Venus’s cloud tops.

All worlds begin in ice and fire. The great cow licked the Ginnungagap from the universal ice. Out of the void the world tree had grown. The heavens declare shamanic truth.

‘Moon-cow,’ she announced to the great disc, speeding unseen on its outward course. ‘I call you Moon-cow, life-licker.’

Half an hour down the highway she pulled in at a truck stop. She needed fuel for machine and body. Shamanic trances left her as hungry as a logger. The park was full of truck trains headed north with supplies for the outlying towns before winter closed in. The diner was full of loud drivers. They followed Oksana with their eyes as she took the loaded tray to the furthest table. Her expression said, leave me alone. Her Sibirsk jacket said, respect, boys. Her half-inch of blonde stubble and tattoos said, if you want to think I am a lesbian, that’s all right. Her thirty centimetre hook-tipped hunting knife said, I can take the knob off your dick so fast …

The radio was tuned to the same country station she had half-listened to in the car. Oksana ate her heaps of food and helped her diffuser work on the last of the arak and the fungus with twelve glasses of tea. She paid the pile of chits the sexually oppressed waitress had left on her table and felt the truckers’ eyes follow her back out into the car park.

She smelled coming winter in the dust of the last warm autumn day. The night was immense. The truck stop was a frail lantern hanging in the wilderness. A kind-of-pretty trucker boy was standing in the middle of the lot, gazing ecstatically into the sky.

‘If you stare too long you can get lost in them,’ she said. The spirits of many shamans are still wandering out there; looking for the path home.’

That’s your car, the one with antlers?’ The boy’s voice was soft, high-pitched, feminine.

Cute, Oksana Telyanina thought. She said, ‘How long have you been following the way?’

‘I’m just a beginner; I got some books out the travelling library, optical-Roms, on-line newsgroups. Teach-yourself-shamanism.’

‘I think we’re condemned to be beginners all our lives,’ Oksana said.

The boy slowly turned his head, tracing an arc across the night.

‘You can’t see it at home, too much light. Out here, it’s beautiful.’

Oksana blinked the café neons out of her eyes and saw what it was that entranced this strange boy. A bridge of light hung in the sky, soft as powder, growing in definition as her eyes acclimatized to the dark. Intellect told her it was the mingled tails of the comets that had come out of Éa, falling in towards the sun. Instinct could not believe that. It was a star-bow slung across heaven, the way of the spirits between the branches of the world-tree.

The young man and the fortysomething woman stood silent and watching for a timeless time. Then the orgasmic gasp of airbrakes and the sudden headlight dazzle of a bus pulling into the diner broke the enchantment.

‘I really do like your antlers,’ the boy said. ‘Where are you headed?’

‘Back to Irkutsk. You?’

‘South,’ he said, and smiled.

South. Where the geese are flying, where the salmon are swimming, where the reindeer are migrating, where the winds are blowing, where the rains are falling and the starbow is aiming; where the strange boy is travelling.

South, where you will be flying.

Are you answered, Oksana Mikhailovna?

All things may be host to the spirits.

She turned to thank the strange boy for his gift but the only other people in the car park were the bus passengers, eager for the light and warmth and companionship of the diner.

3

Samburu control knew better than to argue when Oksana brought her Antonov 72F straight in along terminum. Because it was run by the United Nations, staff changed all the time at Samburu. The new director would try to assert his authority but Oksana Telyanina kept bringing her rattling old transport in through the I-Zee.

‘Hi, you in the back,’ she said to her cargo, which today was two engineering advisors and several tons of military hardware. ‘We’re going to be landing at Samburu shortly, so fasten your seat-belts and you, yes, you, who’s been smoking despite the fact that I don’t allow it on my ship, this time you stop it. You on the right, you can see the Merti plain and the old East African highway. You on the left will have the best view of the Chaga you’ll ever get. Thank you for flying Sibirsk, the official airline of the United Nations Aid Force in Africa, here’s some music to get you down.’

She sat back in her seat and hit the button on the cell player with a well-practised tap of the boot. One hundred watts of Russian death-thrash rocked the little Antonov.

Aid Force. As fat a lie as ‘engineering advisors’.

The icons and knotted leather talismans hung from the ceiling swayed as Dostoinsuvo, which was the name of the An72F transport, hit a thermal rising from the Nyambeni hills. From two thousand metres the frontier between worlds was sharp as a cut. The clear definition evaporated at ground level, where Earth and Chaga wrapped each other up in fractal coils; bush grass and hexagons of brightly coloured moss spiralling inwards. Up to a kilometre south of terminum thorn acacias and baobabs stood among the land corals, secure now that the northern march had halted and entrenched along a front roughly conterminous with the equator. The uplift of the Great Wall five kilometres in was a definitive boundary at ground level; from a height it melted into just another pattern in the many-coloured world-carpet. Terminum was not a line of division. It was a place of meeting. The hemispheres of the brain, the mind and the body, the gross and the subtle, the material and the spiritual.

The proximity alarm flashed. An I-Zee patrol was interrogating Dostoinsuvo’s AI, querying course and manifest details. The interceptor appeared alongside, demorphing from savannah camouflage: a sin-black stealth, all fins and angularities. It carried Kenyan Air Force markings; from the side window Oksana could see the pilot was as blond and crew cut as she.

‘Hold your missiles, Kansas boy,’ she said to herself. ‘You can trust me. Today.’

She waved to the young pilot, hand-jived to the cock-pit radio blare. The stealth rolled away and faded into invisibility. Arrogant bastard. The fucking things were inherently unstable. They only flew by constantly averting disaster. Crash their AIs and they would come fluttering out of the sky like camouflage confetti. Not like Dostoinsuvo; she was a real Africa plane. Not beautiful, with her high wings and tails and stubby body and big over-wing STOL turbofans. Not wicked, like the stealths, but she would go anywhere for you, do anything, forgive any sin against her. But you had to be an Africa pilot. She would not do it for an ‘aeronautical advisor’. You had to have respect for ship and sky and soil. And spirit.

The memory came bright and sharp. She was three weeks qualified on jets, fresh off prop-busters on the oil-crew runs up country. Dmitri had called a meeting: unusual. Sibirsk’s worker-shareholders gathered in Hangar Five, the one big enough to service the 142s. In came Bakhtin, accountant-hero; he had put together the buy-out package when Aeroflot came apart. He liked games. Aeroflot had let the plant go cheap, but held the landing slots in a death-grip and the bankers had their fists tight up the comrade-stakeholders’ asses. Absolute silence. Then, the grin. No one had ever seen such a thing on his face before.

‘Comrade shareholders, I have a deal!’

That big thing down in Africa, that no one knew what the hell was going on: the UN had accepted their tender. Sibirsk was cheap, it had the resources and it was desperate enough to move at once. But the collective was a democracy; this must be put to the vote.

On her left was an old Aeroflot supersonic man, flew that Tu144 all the way to Mars and back. On her right was a helicopter man, ran gunships in Chechnya for the Russians, then Hinds in Tunguska for the Siberians. In the middle, this kid, sharp, bright, excited as hell, twenty-three years old. And she stuck her hand up with the others and was counted.

She could not believe she had ever been that young. Twenty years flying down in Africa. Places, faces, cities and lovers, all drowned by the Chaga. Twenty years flying over it, around it, your coming and your going and your every act governed by it, but never once inside it. She thought, in that time, your one enduring relationship has been with this plane. Then she thought, even that has been rebuilt and modified and upgraded so many times that there is not one piece left of the Dostoinsuvo that first captured your heart. No, the one thing that has lasted, that has grown and developed like a relationship should, is the Chaga; and that affair remains unconsummated: sterile.

She looked south across the mottled crimsons and jade greens and yellow ochres. On this approach you could sometimes see the snows of Kirinyaga catch the sun and kindle, higher and whiter than you ever imagined. There was a fantastical city growing in its foothills; the satellite photographs gave hints of organic skyscrapers, graceful boulevards, garden villages, living factories. On night flights she had sometimes glimpsed patterns of lights deep in the Chaga.

Dostoinsuvo warned her that they were approaching the safe floor. Oksana switched to auto-land; the starboard wing dipped. The otherworld vanished underneath the fuselage. Samburu lay ahead, the old UNECTA base, immobile since terminum stabilized, white as spilled salt on the burned buff of the plains. The dark stain spreading behind it like a shadow.

They never grew smaller, the camps.

‘I’ll take this one myself,’ Oksana told Dostoinsuvo. The stick came alive in her grip as she brought her little aeroplane down through the blue haze of wood smoke to the ground.

4

’How will I know him?’ she had asked Ali from Cairo, in Damascus. Ali from Cairo, in Damascus, despite his Indian silk suits and his affectation of Ottoman opulence, was just another street boy lured like a moth by the pheromone of UN money. He was the smiling front of the UN-only club at the airport, and he knew all the Faces and some of the Names. Whatever you wanted, whatever you needed, whatever got you screaming like an animal, could not ruffle him. Nothing got round those tiny serial-killer shades.

‘He will know you,’ Ali from Cairo, in Damascus, said. ‘This is where you are to go when you get to Samburu, and when.’ He took a kiddy’s magic slate from the inside pocket of his silk suit. Darker-on-dark were a level, a room number, and a time. ‘You have it?’ Oksana nodded. Ali from Cairo pulled the little cardboard tab that erased the message.

‘He will tell you what to do, where to make the pick-up.’

‘I said I’m not taking any passengers.’

‘You do not give orders in this. There is a system. These people have been waiting a long time. Every day longer they must wait, the greater the risk of them being caught, and if they are caught, they will take the operation with them.’

‘How many?’

‘You will be told that at Samburu.’ He poured chilled thimblefuls of vodka. The heat was peeling off the concrete in sheets. Oksana held up her wrist. The strapping was already beginning to be absorbed.

‘I don’t have my protection any more.’

She could have watched the operation – they had taken the pump out under a local – but it had seemed too much like the amputation of part of herself. It felt like a betrayal of her body, though the faithful little pump would have been the thing that betrayed her, in the end. Those plastics and silicon osmotic gates, transforming, exploding in her wrist. She wondered briefly what the black medicals had done with it. Everything had a market price in Damascus.

Ali from Cairo pressed the tiny, iced glass on Oksana.

‘Take it. I insist. A goodbye to a valued customer. I drink a toast to you because, personally, I think you will almost certainly die, and I will miss you. Luck.’

‘Fuck you,’ Oksana said. The glasses kissed. She swallowed the Stolichnaya down. White UN aircraft taxied and turned in the heat-dazzle. Ali from Cairo, in Damascus, smiled, but his shades betrayed nothing.

5

Samburu strip was theoretically the sovereign territory of the Kenyan government. Like everything over which the Kenyan government claimed jurisdiction, it was controlled by someone else. The UN ran the strip and the base and the camps; the whole I-Zee from Chisimaio on the Indian Ocean to Libreville on the Atlantic. The Chaga ran everything south. What the Kenyan government really ran was a requisitioned game lodge that was its Parliament House, and the ten shops, matatu garage, eatery, two churches, shebeen and graveyard that constituted Archer’s Post; capital of the Republic of Kenya.

The Republic of Kenya’s representative at Samburu base was Corrupt Carmine. Oksana liked her immensely. She had the baldest head, the biggest mouth, the most serious footwear and shades of any woman she had ever known. Her title was gross slander. She was not corrupt. She creamed. She taxed. She sorted things.

Her sawn-open Landrover was waiting at the stand as Oksana powered down the engines.

‘You have them?’ Corrupt Carmine asked as Oksana came down the tail ramp. Kenyan soldiers in desert camouflage moved to assist the engineering advisors with their engineering. None looked over seventeen. All had come from the camps. There was no shortage of willing recruits there. Oksana handed Corrupt Carmine the stack of video cells.

She shook her smooth black head at the cover of the topmost video. It showed a naked white woman with big hair pushing breasts that hung to her waist towards the lens.

‘Why should they desire such a thing? That is not a woman.’

‘White meat keeps them flying right.’

‘The darker the meat, the richer the flavour, m’zungu. And they show them on CNN talking to their wives and children. Hey! You there! Get away!’

A group of men from the camp had seen the aircraft land and had come up the dust road to the perimeter wire. They hoped it might be unloading aid. They would be at the head of the mob when they opened the gates. Corrupt Carmine knew to move fast. Once word spread there would be a feeding frenzy. She pulled a big rungu out of her Landrover and ran over the wire.

‘Go! There is nothing here for you!’ She slammed the wire with the round head of the rungu. The men flinched back. Corrupt Carmine reversed the stick and jabbed it through the mesh. It caught one of the men in the ribs. He yelped, started to protest. Corrupt Carmine shouted him down.

‘You know who I am. I know who you are. I know your faces. If you care for your friends, your families, you will do what I say.’

They muttered and lingered, not wanting to be seen bested by a woman – a government woman – but they went.

‘You have to be harder than they are, or they will take you,’ Corrupt Carmine said.

The boy soldiers had stopped work. One of the advisors was consulting his PDU and pointing to the south west. Everyone was looking where he pointed. Corrupt Carmine took off her serious shades. Oksana unfocused her eyes, depolarizing the optomolecules bonded to her corneas.

High clear blue, dry season sky, hazing yellow with dust where it touched earth. A daytime star suddenly flared and faded.

One thousand four hundred and eighty-eight to go.

Corrupt Carmine drove Oksana the kilometre to Samburu base in the heat and the dust. Every time she came there were more portable cabins shoved up around the tractor units. Their cheapness and meanness disheartened her each new shack was a declaration that Samburu base would never move again. The accommodation and research units piled ten storeys high on the tractor beds were getting shabby: paint peeled; gutters sagged; birds’ nests clung to overhangs. The big blue UNECTAfrique logo – a stylized Kilimanjaro bracketed by two crescents – was faded almost to invisibility.

Corporate money had built the mobile bases on the expectation of exploitable resources in the Chaga. What UNECTA found in there were half-living, half-machine systems of fullerene carbons that manipulated the world at the atomic level. They did not deal. They did not speak. They transformed. They could make anything out of anything. They were the death of western industrial capitalism. The industrials took what would not burn them – the organic circuitry, the cell memories, some pharmaceutical applications – and left the agency it had created to explore and exploit the Chaga to wither.

The prime function of the inderdiction zone slammed down along the equator was geopolitical, but it served the transnationals well as an embargo against a tsunami of cheap nanofactured goods from the south.

Oksana noticed scabs of rust on the tractor treads. For a thousand kilometres this unlikely collage of creeping skyscrapers linked together by swaying airbridges and power conduits had kept pace with the advancing Chaga, crossing plains and hills, fording rivers, felling forests in its path. Fifty metres every day. Here at the feet of the Nyambeni Hills, that march had ceased, and the base had halted and died. Better to have ended like the others, Oksana thought as the elevator platform rattled down its chain drive: trapped, lassoed by Chaga mosses, overgrown with corals and pseudo-fungi, absorbed into a new architecture. Better metamorphosis than the death of the spirit.

The elevator platform choked twice before hoisting Oksana up to level five. A Kenyan Army teenager checked her ID and base pass. They pick them young because they are malleable and they have absolutely no restraint, Oksana thought.

Room 517 was the old physical recreation centre. Treadmill, weight machine, exercise bike and yoga mat were squeezed into a three metre box. Someone had ripped out the sound system to sell on the black market. The jacuzzi still squatted on the balcony. Oksana peered in. Sin dry. A little pale scorpion scuttled down the drain at the touch of her shadow.

She remembered an evening here, in another land, with a cute American called Damon, and a few rolls of the killer skunk they used to grow in the roof gardens. A small celebration of a new moon in the sky. A lot of laughing, then. Almost fifteen years since the Big Dumb Object had gone into orbit between earth and moon.

Oksana leaned on the rail, looked across at the Chaga. No chemical communication from it on the wind today. It clung close to the ground under the haze, closed and secretive. Oksana passed time by thumbing through old body-building magazines. Someone had clipped out the faces of all the male models.

A fistle at the door.

Suddenly Oksana was inexplicably afraid.

Corrupt Carmine entered the gym.

It was like someone had replied to your anonymous small ad for leather sex and when you went to meet him you found it was your husband.

‘Yes,’ Corrupt Carmine said, anticipating any number of Oksana’s questions. She unfolded a clasp knife. She seized Oksana’s hand and made a small cut in the ball of her thumb. Oksana was still wincing, more in surprise than pain, as Corrupt Carmine took a cell memory from the pocket of her jeans and pressed the bloody thumb to it.

‘It’s imprinted,’ she said. ‘Only you can open it.’

‘What’s in it?’

‘A course. Only activate it once you cross terminum. It also contains false cargo manifests, in case they try to interrogate your AI. You’re carrying medical supplies. I have logged you a flight plan up to Kapoeta.’

‘Sudan.’

‘Yes. You will fly there tomorrow morning. The airstrip guards have been paid. The others will be waiting for you, they are coming in tonight, by surface transport.’

‘I told Ali from Cairo no passengers.’

‘We have to make the most of every chance we get. I should tell you, a helicopter patrol from Lake Baringo destroyed a truck convoy yesterday – blockade runners, almost certainly.’

‘One of the stealths checked me out on the way in.’

‘They are under orders to show scalps to justify their obscene expense.’

‘“They”.’

‘What?’

‘You said, “they”.’

Corrupt Carmine looked at her as if she were a bright child who has said a cretinous thing. She tossed Oksana the tiny bloodstained sack of navigation fullerenes.

‘Why, Carmine?’

‘This is my country,’ she said. Her shades glared. She held out a hand. ‘Good luck, m’zungu.’

Oksana shook her hand and understood why the black woman was so hard on the refugees. They had all made the coward’s choice and run from the Chaga. But it had given them a second chance: they did not have to remain camp people. There was a way, for the brave, for the visionary, but they kept making the coward’s choice, day after day.

Yes, Oksana Mikhailovna, you can think that because you do not have a choice to make, now.

The half-healed scars on her wrist itched.

6

The wind shifted in the night, the strong, hot wind blowing out of the heart of the Chaga. It rang the chimes in the window of the cabin Oksana Telyanina had been given. It blew through the cramped room. It blew through Oksana’s sleep, shattering it. The wind from the South smelled of spice and rot and secret sexual places and frankincense and oil. It smelled of night doubts and hopes. Knowing she would not sleep again that night, Oksana went to the window. The stars were bright and so close she could imagine their oppressive weight on her neck. Venus and the atrocities the Chaga-makers were working on her were below the horizon: both moons were high. The Big Dumb Object’s soft green oval floated above the watch-fires of the camp. Tonight there was no sound of shooting from there.