24,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: New Directions in Ethnography

- Sprache: Englisch

Recognized as a finalist for the CAE 2018 Outstanding Book Award!

Part historic ethnography, part linguistic case study and part a mother’s memoir, Kisisi tells the story of two boys (Colin and Sadiki) who, together invented their own language, and of the friendship they shared in postcolonial Kenya.

- Documents and examines the invention of a ‘new’ language between two boys in postcolonial Kenya

- Offers a unique insight into child language development and use

- Presents a mixed genre narrative and multidisciplinary discussion that describes the children’s border-crossing friendship and their unique and innovative private language

- Beautifully written by one of the foremost scholars in child development, language acquisition and education, the book provides a seamless blending of the personal and the ethnographic

- The story of Colin and Sadiki raises profound questions and has direct implications for many fields of study including child language acquisition and socialization, education, anthropology, and the anthropology of childhood

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 342

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

New Directions in Ethnography is a series of contemporary, original works. Each title has been selected and developed to meet the needs of readers seeking finely grained ethnographies that treat key areas of anthropological study. What sets these books apart from other ethnographies is their form and style. They have been written with care to allow both specialists and nonspecialists to delve into theoretically sophisticated work. This objective is achieved by structuring each book so that one portion of the text is ethnographic narrative while another portion unpacks the theoretical arguments and offers some basic intellectual genealogy for the theories underpinning the work.

Each volume in New Directions in Ethnography aims to immerse readers in fundamental anthropological ideas, as well as to illuminate and engage more advanced concepts. Inasmuch, these volumes are designed to serve not only as scholarly texts, but also as teaching tools and as vibrant, innovative ethnographies that showcase some of the best that contemporary anthropology has to offer.

Published volumes

Turf Wars: Discourse, Diversity, and the Politics of Place

By Gabriella Gahlia Modan

Homegirls: Language and Cultural Practice among Latina Youth Gangs

By Norma Mendoza-Denton

Allah Made Us: Sexual Outlaws in an Islamic African City

By Rudolf Pell Gaudio

Political Oratory and Cartooning: An Ethnography of Democratic Processes in Madagascar

By Jennifer Jackson

Transcultural Teens: Performing Youth Identities in French Citȳs

By Chantal Tetreault

Kisisi (Our Language): The Story of Colin and Sadiki

By Perry Gilmore

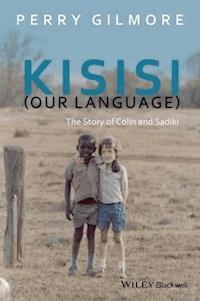

KISISI (OUR LANGUAGE)

The Story of Colin and Sadiki

Perry Gilmore

This edition first published 2016 © 2016 Perry Gilmore

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Perry Gilmore to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gilmore, Perry. Kisisi (our language) : the story of Colin and Sadiki / Perry Gilmore. pages cm. -- (New directions in ethnography ; 6) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-119-10156-7 (cloth) -- ISBN 978-1-119-10157-4 (pbk.) 1. Languages, Mixed--Kenya. 2. Languages in contact--Kenya. 3. Children--Language. I. Title. II. Series: New directions in ethnography ; 6. PM7802.G55 2015 417.22096762--dc23

2015012853

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover image: Photograph taken by Perry Gilmore at the Gilgil Baboon Research Project Headquarters on Kekopey Ranch near Gilgil, Kenya in 1975.

This book is dedicated to my son, Colin Gilmore, and my husband David Smith.

I am inspired by and long for you both every day.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Map

Prologue

Notes

Chapter 1: Uweryumachini!: A Language Discovered

Notes

Chapter 2: Herodotus Revisited: Language Origins, Forbidden Experiments, New Languages, and Pidgins

Notes

Chapter 3: Lorca's Miracle: Play, Performance, Verbal Art, and Creativity

Notes

Chapter 4: Kekopey Life: Transcending Linguistic Hegemonic Borders and Racialized Postcolonial Spaces

Notes

Chapter 5: Kisisi: Language Form, Development, and Change

Kisisi Lexicon

Kisisi Syntax

Tense and Aspect

Miscommunication, Maintenance, and Repair

Notes

Epilogue

Notes

In Memoriam

References

Index

Plates

EULA

List of Illustrations

Plates

Plate 1

Proud pretend hunters look out across the savannah from high on the hillside cliff.

Plate 2

Colin and Sadiki became inseparable best friends, spending all their daylight hours together for the 15 months that they were neighbors on a remote Up-Country Kenya hillside.

Plate 3

A panoramic view of the vast Kekopey ranch and flamingo-covered Lake Elementaita.

Plate 4

Colin and Sadiki look out across the savannah on a visit to Lake Elementaita where we sometimes picnicked.

Plate 5

The Red House, the Gilgil Baboon Project headquarters and our home, was frequently visited by the baboon troop who would sit on the windows and the patio and often play on the roof. For their safety, the boys had to be in the house with all the windows and doors locked when the baboons came.

Plate 6

“The Pumphouse Gang” baboons were known predators who could hunt co-operatively and take down large prey.

Plate 7

Our multilingual hillside community was made up of families who worked for the ranch and for the baboon research project. From left to right: Joab and William who worked for the baboon project, Sadiki, his father, Elim, young sister Maria, Moses (Sadiki's uncle and a worker on the ranch), a visiting relative of Moses, Mary (Moses' wife and their baby), Margaret (Sadiki's sister), Laiton (Sadiki's mother) holding baby sister Jane, and Peninah, Sadiki's older sister.

Plate 8

Sadiki's family members sometimes came from Samburu to visit. They dressed more traditionally. This beautiful aunt of Sadiki's asked me to take her picture. Her husband stands in the distant background. They had come to see the boys who loved each other so much that Mungu (God) blessed them with a language that was so complicated no one else could understand them.

Plate 9

The boys spent time together with each other's families. Sadiki's father taught the boys to make arrows and often took them with him when he went to do maintenance checks and repair at the pumphouse at the bottom of the cliff. Colin's parents took the children on short trips across the ranch to the lake or the hot springs. In this photo we are on a shopping trip in the town of Nakuru buying groceries for the month.

Plate 10

Sadiki and Colin carve arrows that Sadiki's father taught them to make.

Plate 11

A visiting entomologist they called Bwana Dudu (Mister Bug) let the boys use his insect net to collect bug specimens for which he paid them a few shillings.

Plate 12

Colin and Sadiki played long hours with Paka, Colin's adopted feral kitten. They loved to giggle and call her “Silly Paka” when she chased them and bit at their ankles.

Plate 13

Colin's father examines animal tracks with the boys.

Plate 14

Colin and Sadiki run with me through the tall grass on a picnic near Lake Elementaita.

Plate 15

Children from the Gilgil Preschool join children from the hillside at Colin's sixth birthday party. I am playing guitar and singing with the children – Sadiki's sisters and their visiting friend, Joab's twin sons, Colin and Sadiki, and their “wazungu” (white) schoolmates. This was an unusual mix since the “wazungu” children rarely interacted socially with local African children.

Plate 16

Colin and Sadiki often helped me make bread, shaping the flexible dough into the shapes of cars and trucks. Alan Wolf, an American friend from their preschool, joins the boys beating and shaping the dough. Alan's father was a visiting scientist studying sunbirds and their family was staying in a cottage at the Gilgil Club.

Plate 17

Colin and Sadiki take turns playing with a sling shot and a makeshift weapon they fashioned from a stick and an empty shotgun shell – one of many that could be found scattered across the landscape.

Plate 18

Sadiki and Colin look very serious as they plan a pretend hunt. They sometimes would hide in the tall grass and sneak up on a herd of Thomson's gazelles. Once they got really close they would pop up and let out shouts causing the “tommies” to scatter.

Plate 19

Sadiki and Colin loved being “silly” and enjoyed making faces for the camera.

Plate 20

Colin and Sadiki close the paddock gate.

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Pages

ix

x

xi

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xix

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book has been four decades in the making and has benefited from myriad conversations with friends, family, colleagues, and students who have helped shape my thinking and encouraged my efforts. I am deeply indebted to them all. My late husband, David Smith, was my strongest and most enthusiastic supporter. His research on language dialect, variation, and change inspired my own study. Reading his articles on pidgin and creole languages before I went to Kenya introduced me to the study of language contact phenomena and their potential comparisons with child language development. This background knowledge, along with my own professional interest in child language studies, contributed to my heightened awareness of the compelling significance of Colin and Sadiki's creative language invention and prompted me to document and record their everyday talk and social interactions.

I owe special thanks to colleagues and friends including Ray McDermott, Shelley Goldman, Michelle Fine, Norma Mendoza-Denton, Bambi Schieffelin, Terri McCarty, Susan Philips, Penny Eckert, Janet Theophano, Deborah Tannen, Aomar Boum, Sarah Engel, Elena Houle, Robi Craig Erickson, Concha Delgado-Gaitan, Jody Gilmore, Juliet Gilmore-Larkin, Beth Leonard, Luis Moll, Lisa Delpit, Nancy Hornberger, Jane Hill, Courtney Cazden, and Shirley Brice Heath. They have all offered much appreciated support, critical feedback, and ongoing dialogue about this very personal research project. This book has benefited from their knowledge, wisdom, interest, and encouragement. Others who also strongly influenced my research while I was at the University of Pennsylvania included Dell Hymes, Bill Labov, Gillian Sankoff, Erving Goffman, and Lila Gleitman.

I was fortunate to have my former doctoral student, Heidi Orcutt-Kachiri, review and edit an earlier draft of this book. Heidi's fieldwork in Kenya, fluency in Swahili, and editorial expertise and generosity made her an invaluable resource. Much appreciation also goes to my graduate student, Susanna Schippers, who proof read an earlier version of the draft manuscript. I am grateful to many students who have participated in my classes in language acquisition, discourse analysis, applied linguistics and the anthropology of childhood. They have raised important questions and provided critical insights about this study over the years. Special appreciation goes to my graduate assistants Satoko Seigel, Shri Ramakrishnan, Lauren Zentz, Katie Silvester, and Paola Delgado.

Colleagues, friends, and family who shared time with me in Kenya were kind enough to read and respond to earlier drafts of this book. I thank Colin's father, Hugh Gilmore, who also helped me record the language data, Shirley Strum, Bob Harding, Andrew Hill, and Barbara Terry. Their critical comments and questions helped affirm memories and further problematize the challenging circumstances of the complex social world we all experienced in postcolonial Kenya. Janet McIntosh also provided more current perspectives based on her recent research on postcolonial settler life in Kenya.

In 2009, my colleague, Peggy Miller, recalling my first publication on the boys' language in 1979, invited me to write about the research anew for an interdisciplinary encyclopedia, The Child, that she was co-editing with Richard Shweder for the University of Chicago Press. I was struck that after more than 30 years Peggy remembered the research so vividly and considered it relevant today. Coincidently, just a few months later, Mikael Parkvall, a Swedish linguist and a pidgin scholar whom I hadn't known, contacted me after discovering the same 1979 article online. Both Mikael's and Peggy's interest in and enthusiasm about the work, after so many years, inspired me to finally reopen the dusty boxes of data that were filled with recordings, films, photos, letters, and journals that I had collected decades before. I am deeply indebted to them both for motivating me and taking the work so seriously. They reminded me of the important responsibility I had to reframe and share this study. Mikael Parkvall additionally provided lengthy and detailed feedback on an earlier draft of this book. His linguistic expertise and generosity were deeply appreciated.

The editorial team at Wiley-Blackwell has been extremely encouraging and has provided a perfect home for the book in the New Directions in Ethnography series. I especially thank Elizabeth Swayze, Wiley-Blackwell's Commissioning Editor, for her strong enthusiasm and persuasive belief in this work. Mary Hall, Editorial Assistant, and Ben Thatcher, Project Editor, have graciously helped make the production phase of publication go smoothly. The series editors, Norma Mendoza-Denton and Galey Modan, provided deeply appreciated professional enthusiasm, astute editorial insights and much of their valuable time.

A writing grant from the Southwest Educational Development Laboratory supported the preparation of my 1979 article on this topic published in Working Papers in Sociolinguistics. Portions of the data presented in this book originally appeared in that article. An earlier analysis of some of the data also appeared in an article published in the Anthropology and Education Quarterly in 2011 in a special issue edited by Nancy Hornberger honoring the work of Dell Hymes. A sabbatical leave from the University of Arizona, College of Education in 2013–2014 provided the opportunity to write the book. A brief retreat in a serene Vermont setting, generously hosted by my friends Robby Mohatt, Justin Mohatt, and Jim Cummings, provided a special space to complete final editorial revisions.

I want to thank my family – Susan Raefsky, Elena, Gary, and Lana Houle, Jodi Smith and Hansil Stokes, Cindy and Tom Ryan, Jesse, Seth and Cameron Meyer, Tommy and Michael Ryan, and Jamie Smith. They have always been a steady support for me and I dearly love and appreciate them all. Aomar Boum, Norma Mendoza-Denton, and Maggie Boum, who are like family to me, were especially supportive while I was writing the book. Also part of my extended family support network here in Tucson are Velma and Bob Rutman on whom I depend for so much. We are all further connected to our African family through Sadiki Elim, my son Colin's cherished childhood friend. Though I have not been back to Kenya since I left in 1976, we have managed to remain closely bonded. There have been many long skype calls with Sadiki, his parents, wife, children, and other family members, including Timothy Leperes Laur and David Laur. The family's complete pleasure and pride in the project have further inspired me to complete the book.

Finally, I am profoundly grateful to two beautiful five-year-old boys, Colin Gilmore and Sadiki Elim, who loved each other unabashedly on an Up-Country Kenya hillside and expressed that love in a language that helped them face the challenges of postcolonial racism that dominated their lives. I am honored and privileged to share their sweet story. It is my hope that the boys will amaze you today as they did me so long ago. Sadiki and Colin's story urges us to look more closely and see all children with a little more awe, wonder, and respect.

MAP

PROLOGUE

Like the Ancient Mariner in Samuel Coleridge's classic poem, I have a story to tell. In Coleridge's Rime of the Ancient Mariner, the old man stops the wedding guest, and with his hypnotic “glittering eye” begins his compelling narration with the words, “There was a ship.” He tells the captivated listener about powerful life and death events that occurred many years before. He tells his tale to leave the listener sadder and wiser from this lesson in humanity but also to find some healing for his own long-held pain. My own story, like the Mariner's, is a deeply felt personal life story that tells of events that took place many years ago. My own narrative might begin with the words, “There was a boy.”

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!