0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: World War Classics

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

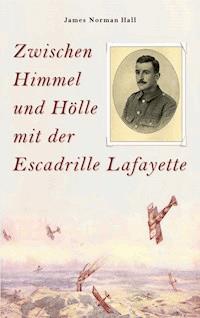

Hall is the perfect adventurer. He could sense opportunity and then blend almost seamlessly into an exciting new situation. As a well-educated American, he had a detached but perceptive view of British society and the rush in the summer of 1914 to create a massive new army.Most important, he had a rare eloquencer as a writer.When World War I broke out, Britain had an army of about 160,000. Millions were quickly recruited and trained. Hall became part of this "mob" which became the stubborn army that stopped Germany's domination of Europe. "Mob" was the soldiers' term; Hall explains, "They fastened the name upon themselves, lest the world at large should think they regarded themselves too highly."In a telling passage, he describes how the French go to war "for Glorious France, France the Unconquerable." It's much the same as the attitude of Americans who fight to bring democracy to lesser peoples. The Brits are quite different; Hall typifies their attitude as "Tommy shoulders his rifle and departs for the four corners of the world on a bloomin' fine 'oliday! A railway journey and a sea voyage in one! Blimey! Not 'arf bad, wot?"Yet, such men walked into one of the bloodiest wars in history. In 1964 - 1973, the U.S. had 58,193 deaths in the Vietnam War. In one morning on the Somme, the Brits lost 60,000 dead. Who today would think of being sent to Iraq, where 4,000 Americans have lost their lives in five years, as "a bloomin' fine 'oliday"?Hall describes daily life in the trenches, where he manned a machine gun and was told never to fire it unless countering a German attack. Otherwise, it would be quickly spotted and ferociously shelled. He explains, "W'en you goes out at night to 'ave a go at Fritzie, you always tykes yer gun sommers else. If you don't, you'll 'ave Minnie an' Busy Bertha an' all the rest o' the Krupp children comin' over to see w'ere you live."It's Hall's first book. He later gained well-deserved fame with Charles Nordhoff in writing 'Mutiny on the Bounty' and other books about Tahiti and the South Pacific. This book, written at the age of 33 and before he became famous, may be his most relaxed, informal, authentic and best work. It's a worthy tribute to 'Kitchener's Mob' and all those who call themselves Brits.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

KITCHENER’S MOB

Adventures of an American in the British Army

James Norman Hall

WORLD WAR CLASSICS

Thank you for reading. In the event that you appreciate this book, please consider sharing the good word(s) by leaving a review, or connect with the author.

This book is a work of personal nonfiction; some details may have been changed or misremembered.

All rights reserved. Aside from brief quotations for media coverage and reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form without the author’s permission. Thank you for supporting authors and a diverse, creative culture by purchasing this book and complying with copyright laws.

Copyright © 2018 www.deaddodopublishing.co.uk

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER I. JOINING UP

CHAPTER II. ROOKIES

CHAPTER III. THE MOB IN TRAINING

CHAPTER IV. ORDERED ABROAD

CHAPTER V. THE PARAPET-ETIC SCHOOL

CHAPTER VI. PRIVATE HOLLOWAY, PROFESSOR OF HYGIENE

CHAPTER VII. MIDSUMMER CALM

CHAPTER VIII. UNDER COVER

I. UNSEEN FORCES

II. “THE BUTT-NOTCHER”

III. NIGHT ROUTINE

CHAPTER IX. BILLETS

CHAPTER X. NEW LODGINGS

I. MOVING IN

II. DAMAGED TRENCHES

III. RISSOLES AND A REQUIEM

CHAPTER XI. “SITTING TIGHT”

I. LEMONS AND CRICKET BALLS

II. “GO IT, THE NORFOLKS!”

III. CHRISTIAN PRACTICE

IV. TOMMY

CHAPTER I. JOINING UP

“KITCHENER’S MOB” THEY WERE CALLED in the early days of August, 1914, when London hoardings were clamorous with the first calls for volunteers. The seasoned regulars of the first British expeditionary force said it patronizingly, the great British public hopefully, the world at large doubtfully. “Kitchener’s Mob,” when there was but a scant sixty thousand under arms with millions yet to come. “Kitchener’s Mob” it remains to-day, fighting in hundreds of thousands in France, Belgium, Africa, the Balkans. And to-morrow, when the war is ended, who will come marching home again, old campaigners, war-worn remnants of once mighty armies? “Kitchener’s Mob.”

It is not a pleasing name for the greatest volunteer army in the history of the world; for more than three millions of toughened, disciplined fighting men, united under one flag, all parts of one magnificent military organization. And yet Kitchener’s own Tommies are responsible for it, the rank and file, with their inherent love of ridicule even at their own expense, and their intense dislike of “swank.” They fastened the name upon themselves, lest the world at large should think they regarded themselves too highly. There it hangs. There it will hang for all time.

It was on the 18th of August, 1914, that the mob spirit gained its mastery over me. After three weeks of solitary tramping in the mountains of North Wales, I walked suddenly into news of the great war, and went at once to London, with a longing for home which seemed strong enough to carry me through the week of idleness until my boat should sail. But, in a spirit of adventure, I suppose, I tempted myself with the possibility of assuming the increasingly popular alias, Atkins. On two successive mornings I joined the long line of prospective recruits before the offices at Great Scotland Yard, withdrawing each time, after moving a convenient distance toward the desk of the recruiting sergeant. Disregarding the proven fatality of third times, I joined it on another morning, dangerously near to the head of the procession.

“Now, then, you! Step along!”

There is something compelling about a military command, given by a military officer accustomed to being obeyed. While the doctors were thumping me, measuring me, and making an inventory of “physical peculiarities, if any,” I tried to analyze my unhesitating, almost instinctive reaction to that stern, confident “Step along!” Was it an act of weakness, a want of character, evidenced by my inability to say no? Or was it the blood of military forebears asserting itself after many years of inanition? The latter conclusion being the more pleasing, I decided that I was the grandson of my Civil War grandfather, and the worthy descendant of stalwart warriors of a yet earlier period.

I was frank with the recruiting officers. I admitted, rather boasted, of my American citizenship, but expressed my entire willingness to serve in the British army in case this should not expatriate me. I had, in fact, delayed, hoping that an American legion would be formed in London as had been done in Paris. The announcement was received with some surprise. A brief conference was held, during which there was much vigorous shaking of heads. While I awaited the decision I thought of the steamship ticket in my pocket. I remembered that my boat was to sail on Friday. I thought of my plans for the future and anticipated the joy of an early home-coming. Set against this was the prospect of an indefinite period of soldiering among strangers. “Three years or the duration of the war” were the terms of the enlistment contract. I had visions of bloody engagements, of feverish nights in hospital, of endless years in a home for disabled soldiers. The conference was over, and the recruiting officer returned to his desk, smiling broadly.

“We’ll take you, my lad, if you want to join. You’ll just say you are an Englishman, won’t you, as a matter of formality?” Here was an avenue of escape, beckoning me like an alluring country road winding over the hills of home. I refused it with the same instinctive swiftness of decision that had brought me to the medical inspection room. And a few moments later, I took “the King’s shilling,” and promised, upon my oath as a loyal British subject, to bear true allegiance to the Union Jack.

During the completion of other, less important formalities, I was taken in charge by a sergeant who might have stepped out of any of the “Barrack-Room Ballads.” He was true to type to the last twist in the s of Atkins. He told me of service in India, Egypt, South Africa. He showed me both scars and medals with that air of “Now-I-would-n’t-do-this-for-any-one-but-you” which is so flattering to the novice. He gave me advice as to my best method of procedure when I should go to Hounslow Barracks to join my unit.

“‘An ‘ere! Wotever you do an’ wotever you s’y, don’t forget to myke the lads think you’re an out-an’-outer, if you understand my meaning,—a Britisher, you know. They’ll tyke to you. Strike me blind! Be free an’ easy with ‘em,—no swank, mind you!—an’ they’ll be downright pals with you. You’re different, you know. But don’t put on no airs. Wot I mean is, don’t let ‘em think that you think you’re different. See wot I mean?”

I said that I did.

“An’ another thing; talk like ‘em.”

I confessed that this might prove to be rather a large contract.

“‘Ard? S’y! ‘Ere! If I ‘ad you fer a d’y, I’d ‘ave you talkin’ like a born Lunnoner! All you got to do is forget all them aitches. An’ you don’t want to s’y ‘can’t,’ like that. S’y ‘cawrn’t.’”

I said it.

“Now s’y, ‘Gor blimy, ‘Arry, ‘ow’s the missus?’”

I did.

“That’s right! Oh, you’ll soon get the swing of it.”

There was much more instruction of the same nature. By the time I was ready to leave the recruiting offices I felt that I had made great progress in the vernacular. I said good-bye to the sergeant warmly. As I was about to leave he made the most peculiar and amusing gesture of a man drinking.

“A pint o’ mild an’ bitter,” he said confidentially. “The boys always gives me the price of a pint.”

“Right you are, sergeant!” I used the expression like a born Englishman. And with the liberality of a true soldier, I gave him my shilling, my first day’s wage as a British fighting man.

The remainder of the week I spent mingling with the crowds of enlisted men at the Horse Guards Parade, watching the bulletin boards for the appearance of my name which would mean that I was to report at the regimental depot at Hounslow. My first impression of the men with whom I was to live for three years, or the duration of the war, was anything but favorable. The newspapers had been asserting that the new army was being recruited from the flower of England’s young manhood. The throng at the Horse Guards Parade resembled an army of the unemployed, and I thought it likely that most of them were misfits, out-of-works, the kind of men who join the army because they can do nothing else. There were, in fact, a good many of these. I soon learned, however, that the general out-at-elbows appearance was due to another cause. A genial Cockney gave me the hint.

“‘Ave you joined up, matey?” he asked.

I told him that I had.

“Well, ‘ere’s a friendly tip for you. Don’t wear them good clo’es w’en you goes to the depot. You won’t see ‘em again likely, an’ if you gets through the war you might be a-wantin’ of ‘em. Wear the worst rags you got.”

I profited by the advice, and when I fell in, with the other recruits for the Royal Fusiliers, I felt much more at my ease.

CHAPTER II. ROOKIES

“A MOB” IS GENUINELY DESCRIPTIVE of the array of would-be soldiers which crowded the long parade-ground at Hounslow Barracks during that memorable last week in August. We herded together like so many sheep. We had lost our individuality, and it was to be months before we regained it in a new aspect, a collective individuality of which we became increasingly proud. We squeak-squawked across the barrack square in boots which felt large enough for an entire family of feet. Our khaki service dress uniforms were strange and uncomfortable. Our hands hung limply along the seams of our pocketless trousers. Having no place in which to conceal them, and nothing for them to do, we tried to ignore them. Many a Tommy, in a moment of forgetfulness, would make a dive for the friendly pockets which were no longer there. The look of sheepish disappointment, as his hands slid limply down his trouser-legs, was most comical to see. Before many days we learned the uses to which soldiers’ hands are put. But for the moment they seemed absurdly unnecessary.

We must have been unpromising material from the military point of view. That was evidently the opinion of my own platoon sergeant. I remember, word for word, his address of welcome, one of soldier-like brevity and pointedness, delivered while we stood awkwardly at attention on the barrack square.

“Lissen ‘ere, you men! I’ve never saw such a raw, roun’-shouldered batch o’ rookies in fifteen years’ service. Yer pasty-faced an’ yer thin-chested. Gawd ‘elp ‘Is Majesty if it ever lays with you to save ‘im! ‘Owever, we’re ‘ere to do wot we can with wot we got. Now, then, upon the command, ‘Form Fours,’ I wanna see the even numbers tyke a pace to the rear with the left foot, an’ one to the right with the right foot. Like so: ‘One-one-two!’ Platoon! Form Fours! Oh! Orful! Orful! As y’ were! As y’ were!”

If there was doubt in the minds of any of us as to our rawness, it was quickly dispelled by our platoon sergeants, regulars of long standing, who had been left in England to assist in whipping the new armies into shape. Naturally, they were disgruntled at this, and we offered them such splendid opportunities for working off overcharges of spleen. We had come to Hounslow, believing that, within a few weeks’ time, we should be fighting in France, side by side with the men of the first British expeditionary force. Lord Kitchener had said that six months of training, at the least, was essential. This statement we regarded as intentionally misleading. Lord Kitchener was too shrewd a soldier to announce his plans; but England needed men badly, immediately. After a week of training, we should be proficient in the use of our rifles. In addition to this, all that was needed was the ability to form fours and march, in column of route, to the station where we should entrain for Folkestone or Southampton, and France.

As soon as the battalion was up to strength, we were given a day of preliminary drill before proceeding to our future training area in Essex. It was a disillusioning experience. Equally disappointing was the undignified display of our little skill, at Charing Cross Station, where we performed before a large and amused London audience. For my own part, I could scarcely wait until we were safely hidden within the train. During the journey to Colchester, a re-enlisted Boer War veteran, from the inaccessible heights of South African experience, enfiladed us with a fire of sarcastic comment.

“I’m a-go’n’ to transfer out o’ this ‘ere mob, that’s wot I’m a go’n’ to do! Soldiers! S’y! I’ll bet a quid they ain’t a one of you ever saw a rifle before! Soldiers? Strike me pink! Wot’s Lord Kitchener a-doin’ of, that’s wot I want to know!”

The rest of us smoked in wrathful silence, until one of the boys demonstrated to the Boer War veteran that he knew, at least, how to use his fists. There was some bloodshed, followed by reluctant apologies on the part of the Boer warrior. It was one of innumerable differences of opinion which I witnessed during the months that followed. And most of them were settled in the same decisive way.

Although mine was a London regiment, we had men in the ranks from all parts of the United Kingdom. There were North-Countrymen, a few Welsh, Scotch, and Irish, men from the Midlands and from the south of England. But for the most part we were Cockneys, born within the sound of Bow Bells. I had planned to follow the friendly advice of the recruiting sergeant. “Talk like ‘em,” he had said. Therefore, I struggled bravely with the peculiarities of the Cockney twang, recklessly dropped aitches when I should have kept them, and prefixed them indiscriminately before every convenient aspirate. But all my efforts were useless. The imposition was apparent to my fellow Tommies immediately. I had only to begin speaking, within the hearing of a genuine Cockney, when he would say, “‘Ello! w’ere do you come from? The Stites?” or, “I’ll bet a tanner you’re a Yank!” I decided to make a confession, and I have been glad, ever since, that I did. The boys gave me a warm and hearty welcome when they learned that I was a sure-enough American. They called me “Jamie the Yank.” I was a piece of tangible evidence of the bond of sympathy existing between the two great English-speaking nations. I told them of the many Americans of German extraction, whose sympathies were honestly and sincerely on the other side. But they would not have it so. I was the personal representative of the American people. My presence in the British army was proof positive of this.

Being an American, it was very hard, at first, to understand the class distinctions of British army life. And having understood them, it was more difficult yet to endure them. I learned that a ranker, or private soldier, is a socially inferior being from the officer’s point of view. The officer class and the ranker class are east and west, and never the twain shall meet, except in their respective places upon the parade-ground. This does not hold good, to the same extent, upon active service. Hardships and dangers, shared in common, tend to break down artificial barriers. But even then, although there was good-will and friendliness between officers and men, I saw nothing of genuine comradeship. This seemed to me a great pity. It was a loss for the officers fully as much as it was for the men.

I had to accept, for convenience sake, the fact of my social inferiority. Centuries of army tradition demanded it; and I discovered that it is absolutely futile for one inconsequential American to rebel against the unshakable fortress of English tradition. Nearly all of my comrades were used to clear-cut class distinctions in civilian life. It made little difference to them that some of our officers were recruits as raw as were we ourselves. They had money enough and education enough and influence enough to secure the king’s commission; and that fact was proof enough for Tommy that they were gentlemen, and, therefore, too good for the likes of him to be associating with.

“Look ‘ere! Ain’t a gentleman a gentleman? I’m arskin’ you, ain’t ‘e?”

I saw the futility of discussing this question with Tommy. And later, I realized how important for British army discipline such distinctions are.

So great is the force of prevailing opinion that I sometimes found myself accepting Tommy’s point of view. I wondered if I was, for some eugenic reason, the inferior of these men whom I had to “Sir” and salute whenever I dared speak. Such lapses were only occasional. But I understood, for the first time, how important a part circumstance and environment play in shaping one’s mental attitude. How I longed, at times, to chat with colonels and to joke with captains on terms of equality! Whenever I confided these aspirations to Tommy he gazed at me in awe.

“Don’t be a bloomin’ ijut! They could jolly well ‘ang you fer that!”

CHAPTER III. THE MOB IN TRAINING

THE NTH SERVICE BATTALION, ROYAL Fusiliers, on the march was a sight not easily to be forgotten. To the inhabitants of Colchester, Folkestone, Shorncliffe, Aldershot, and other towns and villages throughout the south of England, we were well known. We displayed ourselves with what must have seemed to them a shameless disregard for appearances. Our approach was announced by a discordant tumult of fifes and drums, for our band, of which later, we became justly proud, was a newly fledged and still imperfect organization. Windows were flung up and doors thrown open along our line of march; but alas, we were greeted with no welcome glances of kindly approval, no waving of handkerchiefs, no clapping of hands. Nursemaids, who are said to have a nice and discriminating eye for soldiery, gazed in amused and contemptuous silence as we passed. Children looked at us in wide-eyed wonder. Only the dumb beasts were demonstrative, and they in a manner which was not at all to our liking. Dogs barked, and sedate old family horses, which would stand placidly at the curbing while fire engines thundered past with bells clanging and sirens shrieking, pricked up their ears at our approach, and, after one startled glance, galloped madly away and disappeared in clouds of dust far in the distance.

We knew why the nursemaids were cool, and why family horses developed hysteria with such startling suddenness. But in our pride we did not see that which we did not wish to see. Therefore we marched, or, to be more truthful, shambled on, shouting lusty choruses with an air of boisterous gayety which was anything but genuine.

“You do as I do and you’ll do right,

Fall in and follow me!”

was a favorite with number 12 platoon. Their enthusiasm might have carried conviction had it not been for their personal appearance, which certainly did not. Number 15 platoon would strive manfully for a hearing with

“Steadily, shoulder to shoulder,

Steadily, blade by blade;

Marching along,

Sturdy and strong,

Like the boys of the old brigade.”