16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Siegfried Kracauer was one of the most important German thinkers of the twentieth century. His writings on Weimar culture, mass society, photography and film were groundbreaking and they anticipated many of the themes later developed members of the Frankfurt School and other cultural theorists.

No less remarkable were the circumstances under which he made these contributions. After his early years as a journalist in Germany, the rise of the Nazis forced Kracauer into exile – first in Paris and then, after a protracted flight via Marseilles and Lisbon, to the United States. The existential challenges, personal losses and unrelenting hardship Kracauer faced during these years of exile formed the backdrop against which he offered his acute observations of modern life.

Jörg Später provides the first comprehensive biography of this extraordinary man. Based on extensive archival research, Später’s biography expertly traces the key influences on Kracauer’s intellectual development and presents his most important works and ideas with great clarity. At the same time, Später ably documents the intensity of Kracauer’s personal relationships, the trauma of his flight and exile, and his embrace of his new homeland, where, finally, the ‘groundlessness’ of refugee existence gave way to a more stable life and, with it, some of the intellectually most fruitful years of Kracauer’s career.

The result is a vivid portrait of a man driven both by an urge to capture reality – to attend to the things that are ‘overlooked or misjudged’, that still ‘lack a name’, as he put it – and by a need to find his place in a hostile, threatening world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1317

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Contents

Title page

Copyright page

Dedication

Figures

Acknowledgements

1. Siegfried Kracauer – A Life

2. Early Things: Before 1918

3. Revolution, the

Frankfurter Zeitung

and Cultural Criticism around 1920

4. Friendship (Part 1): The Jewish Renaissance in Frankfurt

5. Friendship (Part 2): The One Who Waits

6. The Crisis of the Sciences, Sociology and the Sphere Theory

7. Friendship (Part 3): Passion and the Path towards the Profane

8. The Rebirth of Marxism in Philosophy

9. Kracauer Goes to the Movies: A Medium for the Masses and a Medium for Modernity

10. At the Feuilleton of the

Frankfurter Zeitung

11. Inflation and Journeys into Porosity

12. Transitional Years: Economic Upturn, Revolt, Enlightenment

13. The Primacy of the Optical: Architecture, Images of Space, Films

14. Ginster, Georg and the Salaried Masses

15. The Idea as Bearer of the Group: The Philosophical Quartet

16. Berlin circa 1930: In the Midst of the Political Melee

17. The Trial

18. Europe on the Move: Refugees in France

19. The Liquidation of German Matters

20. Two Views on the Second Empire: Offenbach and the Arcades

21. The Disintegration of the Group

22. Songs of Woe from Frankfurt

23. La Vie Parisienne

24. The ‘Institute for Social Falsification’

25. Vanishing Point: America

26. Fleeing from France, a Last Minute Exit from Lisbon

27. Arrival in New York

28.

Define Your Enemy

: What is National Socialism?

29.

Know Your Enemy

: Psychological Warfare

30.

Fear Your Enemy

: Deportation and Killing of the Jews

31.

Fuck Your Enemy

: From Hitler to Caligari

32. Cultural Critic, Social Scientist, Supplicant

33. The Aesthetics of Film as Cultural Studies

34. Two Boxes from Paris

35. Working as a Consultant in the Social Sciences and Humanities

36. Mail from Germany, Letters from the Past, Travels in Europe

37. The Practice of Film Theory and the Theory of Film

38. Talks with Teddie and Old Friends

39. Time for the Things before the Last

40. After Kracauer’s Death

Bibliography

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Contents

1. Siegfried Kracauer – A Life

Pages

iii

iv

v

ix

x

xi

xii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

458

459

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

460

461

462

463

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

464

465

466

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

467

468

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

469

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

470

471

472

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

473

474

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

475

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

476

477

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

478

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

479

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

480

481

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

482

483

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

484

485

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

486

487

488

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

489

490

209

210

211

212

213

491

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

492

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

493

494

495

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

496

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

497

498

499

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

500

501

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

502

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

503

504

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

505

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

506

507

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

508

316

317

318

319

320

321

509

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

510

331

332

333

334

335

336

511

512

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

513

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

514

515

516

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

517

368

369

370

371

372

373

518

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

519

520

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

521

522

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

523

524

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

525

526

527

528

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

529

530

531

532

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

Kracauer

A Biography

Jörg Später

Translated by Daniel Steuer

polity

Copyright page

First published in German as Kracauer: Eine Biographie © Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin 2016. All rights reserved by and controlled through Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin

This English edition © Polity Press, 2020

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

The translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International – Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Office, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association).

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-3301-5

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Später, Jörg, 1966- author. | Steuer, Daniel, translator.

Title: Kracauer : a biography / Jörg Später ; translated by Daniel Steuer. Other titles: Siegfried Kracauer. English Description: Medford, MA : Polity, 2020. | Summary: "The first definitive biography of one of the twentieth-century's most important cultural theorists"-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019050994 (print) | LCCN 2019050995 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509533015 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509533039 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Kracauer, Siegfried, 1889-1966. | Authors, German--20th century--Biography. | Film critics--Germany--Biography. | Philosophers--Germany--Biography. | Social scientists--Germany--Biography.

Classification: LCC PT2621.R135 Z86613 2020 (print) | LCC PT2621.R135 (ebook) | DDC 834/.912 [B]--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019050994

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019050995

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:

politybooks.com

Dedication

For Mischa and Maxim

Figures

1. Siegfried Kracauer in the 1920s (print from broken glass negative)

2. Siegfried Kracauer in Stamford, New York, 1950

3. Siegfried Kracauer around 1894

4. Siegfried and Rosette Kracauer around 1900

5. Isidor Kracauer around 1900

6. Siegfried Kracauer, about 1907

7. The Philanthropin: In memory of the inauguration of the school building, 1843

8. Georg Simmel around 1911

9. Siegfried Kracauer around 1912

10. Theodor Wiesengrund-Adorno around 1920

11. Leo Löwenthal

12. Ernst Bloch around 1920

13. Margarete Susman, 1911

14. Walter Benjamin, 1926

15. Dolomites 1924: Siegfried Kracauer, unknown person, and Theodor Wiesengrund

16. Benno Reifenberg, 1913

17. Joseph Roth, 1925

18. Elisabeth Ehrenreich around 1926

19. Postcard from Walter Benjamin to Siegfried Kracauer, Paris 1929

20. Charlie Chaplin in

City Lights

(1931)

21. Picture of the company with Ginster (in the back, standing, the fourth from the left)

22. Kracauer in Berlin – a photograph for the publisher S. Fischer, around 1928

23. Elisabeth Kracauer, ca. 1928

24. Siegfried Kracauer, 1934

25. Kracauer at Combloux, summer 1934

26. Elisabeth Kracauer-Ehrenreich in 1935, while in exile in Paris, painted by her brother-in-law, Hanns Ludwig Katz. (Lili here looks like her sister Franziska, who had died a year before.)

27. Rosette and Hedwig Kracauer in their flat in Frankfurt around 1938

28. The streets of Paris. A photo taken by Elisabeth Kracauer in the 1930s

29. A new cinema diagonally across from Kracauer’s room in Avenue Mac-Mahon. Photograph by Lili Kracauer

30. The monster on screen. Still from

King Kong

(1933)

31. Lili Kracauer, New York (1944)

32. Werner Krauß in a scene from

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

by Robert Wiene (1919/1920)

33.

From Caligari to Hitler

: front cover of the first edition

34. Erwin Panofsky in 1966

35. Charles Marville, Rue de Glatigny, Paris (1865)

36. Elisabeth and Siegfried Kracauer, the Americans, with an unknown third person in 1945

37. ‘Talk with Teddie’ – Kracauer’s notes on his discussion with Adorno on 12 August 1960

38. Theodor W. Adorno at Frankfurt University in 1957

39. Siegfried Kracauer in 1953 at Lake Minnewaska, New York. The famous portrait was taken by Elisabeth Kracauer

Acknowledgements

When the German edition of my Kracauer biography appeared in the autumn of 2016 with Suhrkamp, I had the genuine pleasure of being able to thank many colleagues and friends, both for making the book possible in the first place and for their support during the writing process. But the acknowledgements section for this English edition of the book is not the place to repeat this long list of people, for it is indebted to a different group of individuals and institutions.

I had been very pleased to see the positive responses to the appearance of the German edition: everyone seemed to welcome the fact that, at long last, someone had written a biography of this exceptionally interesting and brilliant thinker; there was a sense that he had not received the attention he deserved, that he had remained a blind passenger of intellectual history. The book’s reviews were very positive, some even glowing. I received letters saying such things as: ‘During my studies I read Kracauer and was fascinated. Then, I lost sight of him. And now here comes your book …’. People who had personally known certain of the figures I discuss in the biography also got in touch with me. I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to all of these people.

The book then had the good fortune to be nominated for the non-fiction category of the Leipzig Book Fair Prize, and I was awarded a grant from Geisteswissenschaften International, a programme of the German Publishers and Booksellers Association, which made possible this English translation, published by Polity.

I would like to thank everyone at Suhrkamp Verlag who supported me and gave me such good advice during those exciting few weeks following the book’s publication, in particular Eva Gilmer and Christian Heilbronn. At Polity, I would like to thank John Thompson and Elise Heslinga for taking such good care of the translation project.

The person who has played the most important role in the creation of this English edition, however, is its translator, Daniel Steuer. To his often difficult task he brought great skill and precision. I would like to thank him for his work and for his friendly cooperation throughout the translation process.

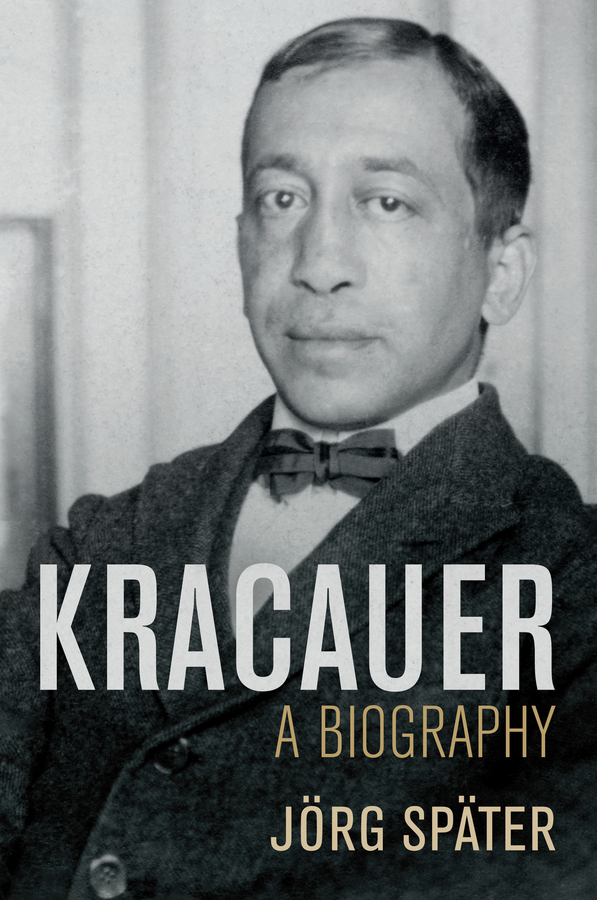

Figure 1. Siegfried Kracauer in the 1920s (print from broken glass negative)

Copyright: DLA Marbach

1Siegfried Kracauer – A Life

The picture shows Siegfried Kracauer. But his face looks bruised. His eyes are not quite straight; his nose seems flattened, and his lips appear to be swollen. His stereotypically Germanic first name weighs him down, while his family name indicates his Jewish ancestry. The neatly arranged bow tie is perhaps too tight. The forty-year-old’s jacket restricts him. In his seemingly uncomfortable attire, he looks out sadly at the world. He does not give the impression that he is one of the leading literary names of the Weimar Republic; he rather looks like someone who has been forced to wear a suit. Perhaps the letter next to him contained some bad news, and he has just sat down, exhausted. The Nazis are coming. The broken glass is a reminder of the fragility of existence. The thought of Heine’s ‘torn world’, in particular, comes to mind – of the modern individual whose mind is torn from the physical world and from society, and who experiences all the loneliness, absence of meaning, and alienation that follow from that separation.1 Kracauer himself spoke of ‘transcendental’ and ‘ideological’ homelessness. But the fact that our hero appears in such a sorry shape, underneath broken glass, is purely accidental. The glass negative had broken at some point, and on the occasion of Kracauer’s hundredth birthday the parts were put back together like a puzzle in order to produce a photo from the not quite complete negative. But is reality not in any case a construction – especially where contingency is involved?

Another picture shows Kracauer twenty years later, this time in America after the war. He is sitting with his back to the camera, working: he is wearing glasses, paper in front of him, a pen in his hand. He seems to be focused. The atmosphere is relaxed; the writer is sitting outside on the veranda, with the trees in front providing shade. Kracauer seems less slight than in the other picture, despite the fact that, in reality, he had neither grown taller nor put on weight. But what does that mean ‘in reality’? In this photograph, we are allowed to look over the author’s shoulder. It is not a typical portrait: we do not see the face of the one portrayed. And yet there is no doubt that this is Kracauer.2 It was taken by his wife, Elisabeth, during a holiday in Stamford, New York, in 1950. It was during this year that, for the first time since 1933, financial hardship and the psychological stress of years of persecution began to abate. Kracauer had just completed From Caligari to Hitler, which would become a classic of the social psychology of film history and a model text for a whole generation of film critics.3 The book did not completely do away with his financial worries, but at least he was in demand again. Film journals asked him to rank the best films, or to compile lists of his best articles from the time of the Weimar Republic, when he was senior editor of the Frankfurter Zeitung. On such occasions, Kracauer was also asked to provide a curriculum vitae. Perhaps the photograph pictures him replying to just such a request.4 I imagine that in the line for ‘Date of Birth’, he would write: ‘I will not give that away, as a matter of principle!’

Figure 2. Siegfried Kracauer in Stamford, New York, 1950

Copyright: DLA Marbach, Photo: Lili Kracauer

As this imagined response suggests, Siegfried Kracauer had a peculiar side, and he had various quirks – such as, for instance, insisting that no one should know how old he was. On his seventy-fifth birthday, he explained this Rumpelstiltskin attitude to his friend Theodor W. Adorno as follows:

This is a matter that is deeply rooted in me and very personal. Call it an idiosyncrasy – but the older I get, the more everything in me revolts against the display of my chronological age. Of course, I am fully aware of the dates, which become more and more ominous, but as long as they do not confront me in public, they at least do not take on the character of an indelible inscription that everyone, myself included, is constantly forced to see. Fortunately, I am still able to ignore the chronological fatality, and that is of infinite importance for the progress of my work, for my whole inner economy. My kind of existence would literally be at stake if the dates were stirred up and attacked me from the outside.5

Kracauer was in a race against time. He wanted to complete a book on the writing of history before his own time came to an end. But there was even more behind this idiosyncrasy. He wanted to live extraterritorially, that is, outside of society and historical time. This was an attitude of not belonging, of shyness, the attitude of someone leading a ‘non-identical existence that cannot be mediated by any generality’.6 This need to be outside of space and time was an expression of Kracauer’s experience of having been a refugee. He had escaped only by the skin of his teeth. As a survivor, he elevated extraterritoriality so that it became the ideal condition for the historian who temporarily leaves his or her own self behind in order to embark on a journey into the past. For Kracauer, it seems, homelessness and alienness were modes of being that may have resulted from compulsion and distress but nevertheless opened up new possibilities for approaching the world.7

If such an extraterritorial character lived outside of any contexts or personal relationships, it would be impossible to write a biography about him. But, in fact, Kracauer had a much more complex relationship to biography than his extraterritorial attitude might suggest. In an article of 1930, written during his ideology-critique years, he condemns biography as ‘an art form of the new bourgeoisie’ and interprets it as a ‘sign of escape’. The more obsolete the individual becomes, the argument goes, the more important individualism becomes in literature.8 Five years later, he wrote a biography himself – of Jacques Offenbach. At the very beginning, he assures the reader that this is not one of those biographies that depicts the private life of its protagonist but ‘a biography of a society in that, along with portraying the figure of Offenbach, it allows the figure of the society that he moved and by which he was moved to arise, thereby emphasizing the relationship between the artist and a social world’.9 The notion of a ‘biography of society’ was inspired by the idea of relating the individual’s life to the general social totality: each side was to explain the other. Kracauer’s portrait of Offenbach’s life thus came to suggest the very opposite of extraterritoriality (despite the fact that the composer too was an émigré). It seems unlikely that the later Kracauer would still have written a rounded and coherent biography of the kind implied by the idea of a ‘biography of society’. By that point, he considered a synthetic mediation of micro- and macro-history, of the general and the particular, to be impossible. Yet in another twist in Kracauer’s relationship to biographical matters, he did recognize in himself, at the end of his life, a synthesizing continuity that he said held together all of his intellectual endeavours. He sketched a philosophy of history in which historical reality, like photographic reality, is an ‘anteroom’, and he thought that this philosophy – aiming ‘to bring out the significance of areas whose claim to be acknowledged in their own right has not yet been recognized’ – had unconsciously been the motivating force behind all of his writings.10 In retrospect, the ego was pushing into the foreground, and this, of course, fits with the fact that Kracauer had written two semi-autobiographical fictional works – Ginster and Georg – and would have liked to write a sequel to them. Although the idea of an objective biography (including a biography of society) might be an illusion, it is nevertheless not illegitimate to attempt one – on the contrary.

The story of Kracauer’s life is unusually fascinating and impressive, and it is therefore difficult to understand why no biography of him has been written before. There is only the small Rowohlt volume by Momme Brodersen and the indispensable chronicle of the Marbacher Magazin (1988), edited by Ingrid Belke and Irina Renz. This is all the more surprising given that there are now two editions of his collected works, each with a carefully prepared editorial apparatus, as well as countless interpretations of him in the fields of German studies and cultural studies. The reason for the absence of a biography is most likely that biographies of literary authors are written by literary scholars, those of social philosophers by sociologists or philosophers, and biographies of theorists of film by film scholars – but Kracauer did not belong to a single academic discipline, and he thus always falls between two stools. When historians write biographies (which are mostly of politicians), they are quick to claim that their protagonist is a representative of a whole age, or that the crisis of modernity is reflected in his or her works, or something of a similar magnitude. I would like to be a little bit more cautious. Kracauer, of course, did not live his life in order to become a symbol for this or that. And yet even a cursory glance at his life reveals that we are dealing with an extraordinary individual, someone about whom much more is to be related than just the details of his private life.

Kracauer was born in 1889 and grew up in Frankfurt am Main in an assimilated Jewish household he experienced as petit bourgeois and bleak. As an adolescent he felt lonely and ugly. He had a stammer, and an academic career therefore seemed unlikely. Once he had gained his university degree in architecture (during which he also studied a little sociology and philosophy under, among others, Georg Simmel), his family urged him to work as an architect to make a living, and for a short while he obeyed. But he saw himself as a writer of cultural philosophy, and in the years immediately after the First World War he went from job to job before finally becoming the literary editor of the Frankfurter Zeitung and a well-respected figure of the Weimar cultural scene. It was mainly because of him that film criticism came to be accepted as an intellectually respectable genre. He was a prolific writer – essays, reviews, articles on questions of philosophy and religion, of sociology and literature, on the newly formed Soviet Union, on the Bauhaus, on the Jewish renaissance, texts on his travels, on streets in Berlin, Frankfurt and Paris, on the detective novel, on hotel foyers and entertainment halls. He came to understand his times by paying attention to the things that were overlooked. In addition, he wrote two novels and an original ‘ethnological’ study of the social environment of Berlin employees. During this period, discussions with his peers Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin and Ernst Bloch were particularly fruitful and formative for his thinking; all three, like him, had Jewish roots.11

When the National Socialists came to power, Kracauer had to leave Germany. He fled overnight to Paris, where he worked as a correspondent for his newspaper. But the Frankfurter Zeitung then dropped him. This was the beginning of a dark period in Kracauer’s life. Although he spoke fluent French and was relatively well connected, his financial situation was precarious. He kept aloof from friends and other emigrants, did not participate in anti-fascist activities, and did not even communicate with Benjamin, despite the affinities between the two, who knew each other from the Weimar period and now again found themselves in the same place, working on similar projects. They were both studying the irruption of modernity in the ‘capital of the nineteenth century’12 as a way of understanding the catastrophe that was unfolding in the present – Kracauer using Jacques Offenbach and operetta to this end, Benjamin using Charles Baudelaire and the Paris arcades. After a planned collaboration with the Institute for Social Research (ISR) on a study of Nazi propaganda fell through, Kracauer also almost fell out with his friends from Frankfurt, Adorno-Wiesengrund and Leo Löwenthal. After the French capitulation in 1940, however, these two helped him emigrate to the United States.

In the United States, Kracauer was revitalized. From the very beginning, he wrote only in English. Supported by various grants, he wrote From Hitler to Caligari, a history of German film which was, in fact, a history of mind and soul during the Weimar Republic. After a period of working as a freelancer, with little success, he became a research advisor at the Bureau of Applied Social Research at Columbia University and a sought-after referee for American foundations. There were new intellectual and social networks emerging, in particular around eminent authorities in visual culture such as Rudolf Arnheim, Erwin Panofsky and Meyer Schapiro (again all intellectuals of Jewish descent). Finally, Kracauer received grants that allowed him to complete two more important books, a theory of film and a theory of history. Although he did not want to return to Germany permanently, he was, towards the end of his life, drawn back to his old – lost, or perhaps never possessed – home. In the 1960s, various publishers, especially Suhrkamp, released new editions of his old texts and translations of his American books. He cultivated his precarious friendships with Adorno and Bloch, and he was a popular guest at two of the colloquia of the legendary research group ‘Poetik und Hermeneutik’ [poetics and hermeneutics] connected to Hans Robert Jauß and Hans Blumenberg. Kracauer died suddenly and unexpectedly in November 1966.

As we follow the life of this subtle observer, we shall travel through some important intellectual environments: we shall visit the Jewish renaissance in Frankfurt and see the workings of the editorial offices of the Frankfurter Zeitung; we shall stand next to the cradle of Western Marxism and come across the activities of the early Frankfurt School; we shall trace the rise and fall of film in Berlin, the capital of 1920s Europe; we shall observe the political battles of the end of the Weimar Republic and witness the catastrophe of the Nazis’ persecution, expulsion and extermination of the Jews; we will see Kracauer fall on hard times while in exile in Paris, and we shall look at his attempts to explain National Socialism; we shall gain an insight into the social and psychological warfare of the Second World War, and into the social sciences in the United States during the Cold War; and we shall witness the surprisingly successful acculturation of Kracauer, then in his fifties, to America, his homesickness for Europe, as well as his perpetual ambivalence towards Germany.

This book on Kracauer is a conventional biography insofar as it deals with his ‘life and work’ – his work because he was a philosophical writer whose work makes his life more significant; and his life because without it his work would be unintelligible and far less meaningful. Both ‘life and work’ were informed by the fundamental need to cope with existence, that is, by the philosophical search for meaning; by the will to capture social reality; by the naked material and physical fight for survival; and finally, by the joy of aesthetically pleasing work.

If I had to add an adjective to the book’s subtitle, it would be ‘social’. This is a social biography because it tries to illuminate the social and historical contexts within which Kracauer acted. It thus traces a kind of parallel progression between these contexts and his life, in particular his intellectual life. The relationships between what would otherwise appear disparate areas should become apparent in virtue of the way in which they are linked by Kracauer, the man, himself, not as a matter of causal connection but of correspondences. The book seeks to bring objective facts, the hard facts and the less solid, porous ones, into relation with the way Kracauer grappled subjectively with these facts, a grappling sedimented in his ‘experiences’. In this way, the book follows Kracauer’s own advice for presenting history: the dominant perspective is at ground level, the close-ups, complemented occasionally by aerial views or the camera panning into long shots.

The ‘social’ aspect also relates to Kracauer’s ‘lifeworld’. Husserl’s notion, incidentally, is at the centre of Kracauer’s work in social philosophy and aesthetics, because, as the sphere that precedes actual thinking, the ‘lifeworld’ is what underlies philosophy. Part of the profane lifeworld I want to illuminate here is the need to secure one’s livelihood, something that continually preyed on Kracauer’s mind, because over long stretches of his life his material situation was precarious. Kracauer’s social life is another focus of the book: his origins; family; teachers and pupils; friendships and enemies; his symbiotic relationship with his partner, ‘Lili’; his professional relationships; those who shared the same fate of escape and exile; the new academic world in the US. I try to describe Kracauer in all these contexts and to reconstruct how others might have viewed him. I am particularly interested in his friendships with Adorno, Benjamin and Bloch: the book paints a portrait of a group that, around 1930, was attempting to create an avant-garde philosophy and, together, managed it – a ‘revue form of philosophy’, as Bloch called it, based on thought images and images of space, characterized by a broader view of the dialectic of enlightened thinking and the simultaneity of culture and barbarism, and motivated by aesthetic interests as well as by social criticism. Even after the group’s erosion and diffusion, the former members remained important points of reference in one another’s work, whether in agreement or disagreement.

In the final analysis, what is at stake in Kracauer’s biography is our access to the world. On the one hand, this refers to Kracauer’s fundamental urge to capture reality, an urge to which his ‘supple thinking’ and his longing for the concrete and living reality of ‘this Earth which is our habitat’ bear witness.13 On the other hand, access to the world refers to the search for one’s place in a world that is often hostile – and even demonic and life-threatening. In this sense, Kracauer’s life encapsulates the human predicament. The second guiding theme of this social biography – after the way Kracauer coped with the demands of material existence – is thus his own analysis of his times.

This book stands in an extraterritorial relationship to research in the disciplines of German studies, literary studies, sociology and film studies. It does not ask which gaps need to be closed, which pictures need to be corrected or completed. At the same time, it stands on the shoulders of such research, especially in literary studies. Without the philological work that made Kracauer’s posthumous papers available, the book would not have been possible. Thorough scholarly analysis of Kracauer’s work has also left little space for new insights. The book is indebted to many ideas, but not to any single interpretive approach; rather, it follows its protagonist along his multifarious paths. Emphasis is put on those biographical elements, episodes and events which, I feel, are best suited to describing and explaining Kracauer’s life. The biographical account proceeds chronologically but episodically, and thus there are numerous spaces that can be taken up by aspects from Kracauer’s lifeworld and social environment. An episode is essentially a fragment: the aim is not to present a coherent (a successful or unsuccessful) life; no thesis will be attacked or defended, no puzzle deciphered.14 Concentrated analysis and narrative passage, macro- and micro-perspectives, and close-ups and long shots all stand next to each other. Several narrative strands are intertwined, and the rope itself is held together by Kracauer, as he moves through and analyses his times, as he finds ways of coping with existence.

In writing this book, I have consulted Kracauer’s complete correspondence in his posthumous papers at the German Literature Archive Marbach. With the exception of a few letters, his correspondence only begins in 1930, when the Kracauers moved to Berlin, because in 1939 Kracauer asked his mother to destroy the letters that he had left behind in Frankfurt.15 Where copies of his letters exist in the published correspondence of other authors – Adorno, Benjamin, Bloch, Löwenthal, Panofsky, etc. – I have followed these. The correspondence with Margarete Susman is part of Susman’s posthumous papers, which are also in Marbach. In addition to the correspondence, I consulted the thematic collections of papers and other materials that form part of Kracauer’s posthumous papers. I spent long hours in the catacombs of the Marbach archive, which house Kracauer’s library. As the biographical sources relating to the time before 1930 are fewer and further between than are those for the years thereafter, I have also drawn on the autobiographical novels Ginster and Georg in writing about the earlier period – keeping in mind, of course, that these are fictionalized.

It seemed natural to make use of these fictional documents because of their obvious autobiographical nature: among men, we are told, there lived one of them who explored them subterraneously – Ginster. Whenever such an italicized sentence or clause appears, it communicates Ginster’s or Georg’s experience. His [i.e. Georg’s] consciousness of being stared at like a stranger was deeplydisturbing …16 Even before Kracauer was driven from his homeland, Ginster and Georg were strangers in Frankfurt. This alienness was a burden for Kracauer as a private person, but it also opened up possibilities for him as an observer of his environment. Kracauer later said, in a remark about Alfred Schütz, that the stranger and exile is able to be more objective than his or her contemporaries back home because exiles are not locked into cultural patterns; they take less for granted. Further, they have had the bitter experience of having been catapulted out of their habitual orbit. As a stranger in a world that had denied him entry into its community, Kracauer discovered the possibility ‘of penetrating its outward appearances, so that he may learn to understand that world from within’.17 It was the fulfilment of this task that helped Kracauer to deal with the exigencies of his existence.

Notes

1

Transl. note: My translation. See Heinrich Heine,

The Baths of Lucca

, ch. 4, p. 312, in:

Pictures of Travel

, trans. Charles Godfrey Leland (Philadelphia: Schaefer & Koradi, 1879), pp. 302–65.

2

On the history of portraits, see Diers, ‘Der Autor ist im Bilde’; the picture of Kracauer on the veranda is mentioned on pp. 585f.

3

According to Jürgen Habermas in an email to the author (7 April 2016). See also Reinold E. Thile (Westdeutscher Rundfunk) to Kracauer (29 September 1965).

4

See Kracauer to Galvin Lambert (

Sight & Sound

), 28 July 1952, or Penelope Houston (The British Film Institute, London) to Kracauer, 29 September 1961.

5

Kracauer to Adorno, 25 October 1963, in

Adorno/Kracauer, Briefwechsel

, pp. 611–13; here: pp. 611f. [Transl. note: A translation of the correspondence between Adorno and Kracauer is forthcoming from Polity. I was able to consult the draft manuscript and have used it in my translations of the passages from the letters, although with various modifications and amendments. All page references are to the German edition.]

6

Mülder-Bach, ‘Schlupflöcher’, p. 262.

7

See

History: The Last Things Before the Last

(Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1995), pp. 80ff.; on the extension of homelessness into an existentialist category, see Öhlschläger, ‘“Unheimliche Heimat”’.

8

Siegfried Kracauer, ‘The Biography as an Art Form of the New Bourgeoisie’, in

The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays

, pp. 101–5; here: p. 104.

9

Siegfried Kracauer,

Jacques Offenbach and the Paris of His Time

, p. 23.

10

Siegfried Kracauer,

History: The Last Things Before the Last

, pp. 4 and 191.

11

A note on Adorno’s name: up to 1942, he called himself Theodor Ludwig Wiesengrund (his father’s family name); in official academic contexts, even before 1933, he called himself Wiesengrund-Adorno (adding part of his mother’s maiden name, Adorno-Calvelli), and in publications from 1938 onward, he referred to himself as T. W. Adorno. When referring to him, I shall follow this pattern.

12

Transl. note: ‘Paris, the Capital of the Nineteenth Century’ is the title of a text by Walter Benjamin, related to the arcades project.

13

Cf. Stalder, ‘Das anschmiegsame Denken’, p. 47; Siegfried Kracauer,

Theory of Film

, p. xi (Kracauer is quoting Gabriel Marcel).

14

See Kracauer’s thoughts on episode films in

Theory of Film

, pp. 251–61.

15

Letter from Siegfried to Rosette and Hedwig Kracauer, dated 16 March 1939.

16

SK,

Ginster

, in

Werke

7, p. 23; Kracauer,

Georg

, p. 112.

17

Siegfried Kracauer,

History: The Last Things Before the Last

. See also Schütz, ‘Der Fremde’, pp. 72f.

2Early Things: Before 1918

Siegfried Kracauer was born on 8 February 1889, the same year as Charlie Chaplin and Adolf Hitler, two figures that would influence his life. His hometown, Frankfurt am Main, was a large city on a river that had developed gradually throughout its history and lay between low mountain ranges, as Kracauer portrayed it in his 1928 novel Ginster. Like other cities, it uses its past to promote tourism. Imperial coronations, international congresses, and a national marksmen’s fair took place inside the city’s defensive walls, which have long since been transformed into public parks. A monument is dedicated to the gardener. Some Christian and Jewish families can trace back their ancestry. But families without ancestry have also developed successfully into banking firms with connections in Paris, London and New York. Cult sites and stock markets are separated from each other only in spatial terms. The climate is mild, the part of the population that does not live in the Westend, and Ginster belonged to it, hardly mattered. As, moreover, he grew up in F., he knew less about the city than about others that he had never seen.1 Kracauer wrote these words before the Jewish citizens of Frankfurt were first stigmatized and deprived of their rights – from 1933 onwards – then robbed and placed in ghettos, and finally deported and killed. Kracauer himself was no longer there at that point; he had moved to the cities where the high priests of capitalism had their connections. In Paris and New York, he didn’t live in the equivalents of Frankfurt’s Westend either, and he mattered even less. But now he knew some essential things about F., the place he had grown up in, that he had not known before.

Siegfried Kracauer had been forced to flee and had lost his home. After 1945, there was no homecoming, but after 1956 there was a return. A letter he received in October 1959 in New York from a lady in Frankfurt is revealing. The letter’s author thought that she remembered two publications by Kracauer, from more than thirty years ago, which had left a deep impression on her: ‘The Brother of the Lost Son’ and ‘The Crime of the Ornament’.2 But Kracauer had never written anything bearing these titles. Maybe, after all these years, the lady had confused a few things. In 1935, Soma Morgenstern, a Jewish colleague of Kracauer at the Frankfurter Zeitung, had published a novel called Der Sohn des verlorenen Sohns.3 And in 1908, Adolf Loos, like Kracauer an architectural critic, had written his famous essay ‘Ornament and Crime’. Finally, Kracauer himself was actually the author of The Mass Ornament (1928). These false attributions may have been pure coincidence, yet no psychoanalyst could have dreamt up a better combination than to have mentioned, in the same breath, ‘the lost son’ and the ‘crime’ in connection with Kracauer. ‘Ach! Hätte mer die Judde noch!’ – ‘If only we still had the Jews around!’ – was a frequent lament after 1945, first when looking about bombed-out Frankfurt (implying that the bombings had been the punishment for the mass murder of the Jews), and then when thinking of the 30,000 Jews who had helped to make Frankfurt what it was and who were now no longer there.4 Siegfried Kracauer was one of them, a ‘Frankfurter Bubb’, a boy from Frankfurt, who spoke the local dialect and came from a family partly of Jewish locals and partly of Jewish immigrants.5 Adolf and Isidor Kracauer, two brothers from Silesia – the former a commercial agent, the latter a teacher – had married two sisters from Frankfurt, Hedwig and Rosette Oppenheim, the former intellectual and highly educated, the latter practically minded, but clumsy in dealing with other people.6

By German standards, Frankfurt am Main had always been a wealthy city, thanks mainly to its being a trading place, something that even many wars had failed to change. After 1240, the prosperous fair enjoyed imperial protection. There was always a very wealthy elite, which had originally developed out of the vestiges of the mediaeval land-owning nobility and then, following the Reformation, been complemented by rich French, Dutch and Italian immigrants, who became Frankfurters. ‘The last addition to the citizenry of Frankfurt before 1866’, writes Selmar Spier, Kracauer’s childhood friend and author of a beautiful book about Frankfurt before 1914, ‘were the Jews, the members of the century-old Jewish community’, who lived in a quarter referred to as the ‘Judde’gaß’ [Jews’ alley], among them Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812), founder of the Rothschild dynasty.7 For the Untermain area of the city, the process of industrialization was neither continuous nor frictionless. Mechanical and chemical companies settled in the outer quarters, but up until the 1870s, the patriarchal ruling forces in the city fought against industrialization, which they saw as a threat to the luxurious lifestyle and trade of Frankfurt. There were also political dangers: in 1866, Frankfurt was annexed by Prussia and lost the status of an independent city state. Despite the city’s conservative – even reactionary – tendencies, the second half of the nineteenth century saw rapid modernization, mainly thanks to its democratically minded citizens, including the emancipatory-minded Jews of Frankfurt. The Eiserner Steg (an iron footbridge across the Main), the Palmengarten (a botanical garden), the opera, the university, the main railway station, and the expansion of the eastern harbour changed the face of the city into that of a modern metropolis. Detlev Claussen summarizes this major transformation as resulting in a ‘paradoxical modernity in Wilhelminian form’: an experience of ‘liberalism as a mixed social form in which the vestiges of feudalism overlap with the forces of industrialism’.8 That was true in particular for the Jewish citizenry: ‘There was equality before the law, and in the empire (although not in Prussia) there was universal suffrage regarding the parliament and freedom of the press and trade’, writes Spier, ‘but apart from that all the oppositions, classes, antipathies, and prejudices that had been produced by 1,900 years of Christianity and 250 years of small state politics were still alive’.9

The Frankfurter Zeitung, Kracauer’s later employer, symbolized the way the Jewish citizenry was entering the bourgeoisie. It was founded by the banker Leopold Sonnemann (1831–1909), who was an ‘Achtundvierziger’ [a forty-eighter] and a supporter of the national parliament in the Paulskirche.10 The paper first appeared in 1856 under the name ‘Börsenblatt’; during the following decade it bore several different names and also began to include a politics section. In 1866, Sonnemann fled from the Prussian troops when they marched into Frankfurt, but soon returned. From November 1866 onwards, the paper appeared as the Frankfurter Zeitung.11 Sonnemann was the prototypical Jewish member of the Frankfurt upper bourgeoisie: he had democratic convictions, was a member of the city council and was a patron of various city institutions, supporting among other things the Städel Institute of the Arts and the building of the opera house.12 He was a social reformer who fought a war on two fronts – against both Bismarck and Lassalle. The paper, which he edited until his death, shared the social and liberal orientation of the Deutsche Volkspartei [German People’s Party], without being a party organ. It was pro-capitalist, and it rejected the skin-deep constitutionalism of the imperial German Reich. The paper was also influenced by the peculiar, paradoxical modernity of Frankfurt mentioned above. Paul Arnsberg, chronicler of Frankfurt’s Jews after 1945, writes: ‘The “Frankfurter” was certainly considered progressive and liberal, but in line with the local character its “infrastructure” was patrician and conservative in an almost Baroque sense.’ Sonnemann established a collegial atmosphere at the paper’s editorial offices, and his editors were independent of him in his role as publisher. But ‘despite all the editorial “conference” democracy, the unwritten law of fixed hierarchies and authority ruled at the offices’, even finding expression ‘in the sorts of furnishings’ to be found at Eschenheimer Straße 81–7.13 As Frankfurt developed into a leading financial, commercial and industrial centre, the progressive FZ also blossomed, becoming Germany’s most respected paper and earning an international reputation. In fact, it was probably even more highly regarded outside of Frankfurt than in the city itself.14 This remained the case when Sonnemann put the fate of the paper in the hands of his grandchildren Heinrich and Kurt Simon.

Siegfried Kracauer’s Frankfurt childhood around 1900 was apparently not a very happy one.15 For a long time, the boy, who everyone called Friedel, knew almost nothing of his family’s history; at home, no one talked about it. Only when death arrived did the uncle [enter] into his childhood, his mind apparently a little mixed up. The mother, too, had had her youth, hidden childhood years of which he knew nothing, and on it went into the past, like a writing desk drawer of unfathomable depth. Ginster vainly tried to pull it open.16

When Kracauer married in 1930 and sought to move to Berlin, the authorities found inconsistencies in the spelling of his name: Kracauer, Krakauer or Krackauer? They demanded information on the C and K question, and this led to some investigation.17 It turned out that his mother’s family, who were from Frankfurt, also had two versions of the family name: Oppenheim and Oppenheimer. Slowly light began to break over the family history.

According to Hedwig Kracauer, Siegfried’s father, Adolf, had been born in March 1849 in Sagan (today Żagań), in Lower Silesia, a centre of cloth manufacture, wool-spinning and wool and linen weaving. The grandfather was an immigrant from Upper Silesia and a member of the synagogue’s council. Adolf had a brother, three years his junior, called Isidor. Hedwig wrote of Isidor that he was allowed to attend secondary school, where he

realized that his life’s work would be dedicated to historical studies. He achieved this goal, but by way of a minor detour. Having passed his school leaving examination with flying colours, he gave in to the wishes of his mother, who wanted him to become a rabbi, and embarked on studies at the theological seminary in Breslau. Although this probably consolidated his deep interest in Judaism, he soon recognized that his talent did not push him toward a clerical but toward an academic career. He therefore soon switched to the University of Breslau, where he studied history, alongside geography and German.18

It was said that Adolf took up a practical profession so that his brother could pursue his studies. Initially, he became a soldier, and then a travelling commercial salesman dealing in textiles, selling the finest English materials, which he himself did not wear.19 The companies he worked for sent him away from Sagan to France, among other places. In the meantime, his younger brother, having completed his state examination and his doctoral dissertation, had joined the Philanthropin (the Realschule of the Jewish community) in Frankfurt, first on a temporary and then, from 1876, on a permanent basis as a senior teacher.20 At the Philanthropin, he met Hedwig Oppenheim (born 1862), the eldest daughter of Ferdinand and Frederike Oppenheim, who ran a wholesale haberdashery business. Hedwig had six sisters, among them Rosette (born 1867), the third oldest. Frederike Oppenheim died young, in 1885, aged only forty-eight, likely of bowel cancer.21 Isidor and Hedwig married, and from 1885 they took charge of the Julius and Amalie Flersheim Foundation, an institution for the education of destitute orphaned or semi-orphaned Jewish boys. Isidor Kracauer also continued to work as a teacher and academic, and he would later write a history of the Jews of Frankfurt between 1154 and 1825.22 Hedwig was his intellectual equal and collaborator. The hard-working couple did not have any children.

In 1888, their siblings also married. Adolf Kracauer was eighteen years Rosette Oppenheim’s senior. When Siegfried was born, his father was already forty years old, and permanently away on business. On those few occasions when his father was at home, the child in Ginster says: I wish you’d be gone again. The atmosphere was suffocating. When the father came home to their modest apartment in Frankfurt Nordend, Elkenbachstraße 18, his havelock [shrouded] … all of the parental home. … Underneath lived the mother, who could hardly even lift the worn cover – she never made it out into the open. This is not to say that Adolf Kracauer was a bad person. He sent his wife away to summer resorts, saved every penny for her and Ginster, and if the meat turned out well for once, soft and without too much fat, he even entered into a jolly mood and told the few jokes he knew, whose punchlines he always forgot. But then, like a rain cloud, the havelock descended again … and the living room became dark. Adolf Kracauer must have been a very sad person, someone who was at odds with his own life. On Sunday afternoons, he went for walks with his family, always the same walk. Ginster hated the streets on a Sunday. They walked through the Westend, where the villas and stately homes retreat behind their front gardens, so that the tarmac cannot touch them. … The ladies and gentlemen sit behind the curtains, or are in the countryside. The father lingered in front of the villas and estimated their value. He would have liked to have lived his life in this style, but was far from being able to afford it. Most likely, he earned even less than his brother, the teacher, whose studies he had helped to finance. After staying in houses in which he had never set foot, he slipped back under the havelock, and Ginster would have liked to join him, and caress him, because Adolf passed the villas in such gloom.23 But this never happened. When Adolf Kracauer died in 1918, Siegfried’s feelings were still blocked. Not a single tear flowed when his father died, even though he could be easily moved by sentimental films or sentimental novels. In fact, he was relieved. According to his sister-in-law, Adolf Kracauer enjoyed perfect physical health throughout his life, although he was a hypochondriac, something for which his family would often mock him. But towards the end of his life, his mental faculties started to fail him,24 and this made it even harder for Siegfried’s mother. It was her son’s intention that she should now have a better life.

Figure 3. Siegfried Kracauer around 1894

Copyright: DLA Marbach, Photo: Schmidt

Figure 4. Siegfried and Rosette Kracauer around 1900

Copyright: DLA Marbach, Photo: H. Collischonn

An only child, Friedel spent a lot of time alone with his mother. She too, like her husband, lacked joie de vivre and a strong ego. Hedwig describes her sister as hard-working, parsimonious and disciplined, strict with herself and others, conscientious, punctual and pedantic, plagued by worries, unstable and introverted, superstitious and pessimistic. She bottled everything up. Very rarely, when life was simply too much for her, she yelled and raged.25 Ginster also speaks of the mother as living life under a depressive veil, even if not the oppressive havelock. Sometimes she declared, for no reason, that she wanted to die: even while she was in a happy mood and laughed. When for once her laughter set in, it lasted a long time, came back repeatedly and drove an alien red flush into her cheeks. The redness could mean the beginning of an awful silence lasting several days; it glowed in cases of injustice; it was a visible language that expressed everything for which words were not enough. Ginster is worried about his ageing mother. First, she loses a tooth, then her back becomes slightly hunched and her cooking gets worse. He observes how she dissolved; she was dismantled like a building, by unseen hands.26 He observes how this woman is broken by the everyday coldness of life and the insensitivity of people who joyfully and enthusiastically tumble into the madness of a war as if that were the happiness in their lives.27 It is likely that little Friedel also felt responsible for his mother, who, in turn, constantly worried about him. They were both single parents.

Often, Friedel went to visit the boarding school of the Philanthropin in Pfingstweidstraße 14. There, he could meet other boys, but most of all it was a second home. The young Kracauer probably liked the domestic and intellectual worlds of his uncle and aunt better than his first home. In Ginster, there are numerous admiring passages about the practical skills of the uncle and historian who works with paper, pen, scissors, brushes and glue. As a teacher, Isidor Kracauer not only dispensed knowledge but also instilled patience. In Hedwig’s judgement, he possessed an exceptional pedagogical talent.28 Unlike the death of the father, the death of the uncle (the real uncle, Isidor, died in 1923) is described in great detail in the novel.

Figure 5. Isidor Kracauer around 1900

Copyright: DLA Marbach

Friedel liked to roam the streets of Frankfurt. Like his later self, the grown-up flâneur, the boy sauntered through the city. Kracauer would later write about it in his feuilleton articles: ‘To the boy, Frankfurt was infinite. When, as often was the case, every street lantern floated in a luminous halo of fog, he was pulled out of the house like a sleepwalker and aimlessly ambled through the intangible streets.’ These forays ‘were done in a state of intoxication and produced an incomparable feeling of happiness in me. What characterized them was that they always led me from darkness to light.’29 Friedel walked every street, like a ruler visiting his provinces – incognito, like Harun al-Rashid. The train station was a particular attraction, a place for lingering, where Friedel could be among the people without having to be with them. Here, he dreamt of other places:

Even as a child, I liked to visit train stations. I used to sit on a bench for hours on end and observe, unthinkingly and happily, the travellers who arrived individually and streamed out in swarms. I immersed myself in the departure and arrival boards, and felt a mysterious joy when what they promised came true. I bought platform tickets for particular trains and became excited when, suddenly, the round light on the glass skirting came on, which was the herald of the great event. I allowed myself to be jostled by the mass of people in front of the long carriages, offering no resistance, and finally I would be pushed far out into the loneliness in which the enormous locomotive, far away from the crowd, extended her body along the track.30