Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ryland Peters & Small

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

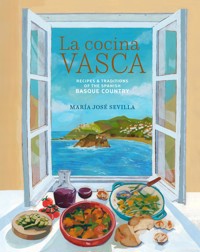

DISCOVER the cuisine from this FASCINATING region through 75 AUTHENTIC recipes from renowned expert MARIA JOSE SEVILLA. Cocina Vasca explores the cooking and traditions of Spain's most EXCITING food destination. Home to some of the world's MOST CELEBRATED restaurants and chefs, with the city of SAN SEBASTIAN at its heart that proudly has 16 Michelin-starred restaurants. Few cuisines have captured more imaginations than that of Spain, but ask a Spaniard where to find the best food in the country and the reply will most certainly be 'in the Basque Country'. The culinary traditions of the region are among the most fascinating in the world and in Cocina Vasca María José Sevilla take readers on an illuminating tour. Along the way she introduces iconic ingredients, unique cooking techniques and traditional dishes that have inspired some of today's most celebrated chefs. An introduction to Basque cooking, ranging from bite-sized tapas known as pintxos to more substantial fish and meat plates as well as delicious desserts, including the legendary Basque Cheesecake. Illuminating essays that shine a light on the most interesting aspects of historical food traditions, as well as the modern scene, are set against a backdrop of the stunning images of the people and surrounding landscape.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 211

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Pedro Subijana, a chef of chefs, a friend I admire and love.

Senior Designer Megan Smith

Senior Editor Abi Waters

Production Manager Gordana Simakovic

Creative Director Leslie Harrington

Editorial Director Julia Charles

Food Stylist Kathy Kordalis

Prop Stylist Max Robinson

Illustrator Lyndon Hayes

Picture Researcher Jess Walton

Indexer Hilary Bird

First published in 2025 by Ryland Peters & Small

20–21 Jockey’s Fields, London

WC1R 4BW

and

1452 Davis Bugg Road

Warrenton, NC 27589

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Text © María José Sevilla 2025

Illustrations © Ryland Peters & Small 2025

Design and commissioned photography

© Ryland Peters & Small 2025

(see page 192 for full picture credits)

Printed in China

The author’s moral rights have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-78879-677-4

E-ISBN 978-1-78879-696-5

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library. US Library of Congress cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

NOTES

• Uncooked or partially cooked eggs should not be served to the very old, frail, young children, pregnant women or those with compromised immune systems.

• When a recipe calls for the grated zest of citrus fruit, buy unwaxed fruit and wash well before using.

• Ovens should be preheated to the specified temperatures.

• To sterilize preserving jars, wash them in hot, soapy water and rinse in boiling water. Place in a large saucepan and cover with hot water. With the saucepan lid on, bring the water to the boil and continue boiling for 15 minutes. Turn off the heat and leave the jars in the hot water until just before they are to be filled. Invert the jars onto a clean dish towel to dry. Sterilize the lids for 5 minutes, by boiling (remove any rubber seals first). Jars should be filled and sealed while they are still hot.

Contents

Introduction

Pintxos: Small & delicious bite-size snacks

From the Vegetable Garden: Vegetable dishes to tempt

At the Market Place: Enjoying mushrooms, eggs & beans

A Traditional Attachment: Recipes for fish and seafood

From the Mountains and Valleys: Cooking meat & sausage

The Sweet Taste of the Basques: Indulgent desserts and cakes

Index

Acknowledgements & Credits

Introduction

My fascination with Basque food started early. My grandmother, Silvia, was a professional cook from Navarra who often prepared traditional Basque dishes while staying with us in Madrid. What I did not know at that time was how immersed I would become in all things Basque. My involvement began in the mid-1980s when I was asked to organise a lunch in London for the British press. The event was to celebrate the achievements of a revolutionary new Basque food movement known as the La Nueva Cocina Vasca (New Basque Cuisine). This movement was started by a group of young Basque chefs in the 1970s. It aimed to update La Cocina Vasca (Traditional Basque Cooking) and marked the beginning of a remarkable success, placing creative Spanish professional kitchens on the world map.

Since the nineteenth century, La Cocina Vasca has been divided into two categories: La Cocina de Siempre, Basque traditional food prepared at home and in popular restaurants, and La Alta Cocina, fine dining greatly influenced by French cooking. By the 1980s, this had already changed. Travelling up and down the country, talking to chefs and home cooks, visiting local markets and, most importantly, tasting dishes, I realised how Basque food, both traditional and reinvented, coexisted in harmony.

Having eventually found the right chef and the right menu, I discovered a history that fired my imagination, inviting me to go further. The menu written for the lunch was going to include a dessert made with apples, puff pastry and Mamia. ‘Mamia?’ I asked the chef. ‘Mamia,’ he said, ‘is a sheep’s milk delicacy that in some caseríos (traditional farmhouses) in northern Navarra is still prepared in the old-fashioned way, using a large traditional wooden pitcher carved out of one solid piece of wood. This utensil has always been known as a kaiku and has a long and interesting history associated with the ancient world of the Basques.’ By then I was intrigued and started looking for answers. I researched and published a paper on the kaiku, then wrote my first book about the special relationship between Basques and food, which in my opinion is without comparison elsewhere in the world.

Who are the Basques? I asked myself. Where do they live? What language do they speak? Where does their intense love of food come from and, equally important, how is Basque food enjoyed and how has such a great reputation been established everywhere within the Iberian Peninsula?

While my area of research on this subject has always been based in Euskadi as Basque Spain is known – Vizcaya, Guipúzcoa, Alava and parts of Navarra – the land of the Basques, Euskal Herria, actually continues much further along the coast, right through to the Pyrenees and into the French provinces of Lower Navarre, Labourd and Soule. This is the reason why I have included several French Basque recipes in this book.

All Basques speak a very ancient language called Euskera. They all share a passion for food, which brings me to my next question: where does the excellent reputation that Basque food enjoys come from? Even today, when wonderful food can be enjoyed all over Spain, ask any Spaniard where you will find the best food in the country and they will most likely say in the north, in the Basque Country. Basques are serious about their culinary traditions, which they respect and follow with passion. (I am not including the new passion for innovative food that is highly impressive but does require skill and a level of professional expertise.)

Basques believe in quality as much as quantity. They are very dedicated when preparing and tasting their delicious dishes, seeking a perfect harmony between people and food to the point where others might think it has become almost an obsession. Virtually all Basques are good cooks, or they aspire to be. I believe that they are born already inspired. They simply love their cooking, as much as to please themselves as to please others. Whether in a bar or restaurant with friends or at home with family, they love to share delicious food whenever possible. In the Basque Country, there are thousands of eating places to choose from, where the quality of the food and the wine (or cider) they love so dearly is guaranteed.

A few years ago, I wrote some words on the Basque passion for cooking and food. Even if the world has changed since then, I believe those words are still valid, I have just added a few more: ‘If I close my eyes to conjure up a scene of Basque cooking, it takes the shape of an earthenware pot, cooking either on a farmhouse range, on a spectacular stove in a txokos (men’s gastronomic society) or in the ultra-modern kitchen of one of the best restaurants in the world. The first is tended by a woman, the second by a man and the third by both men and women.’

Thinking about those words in preparation for this book, I travelled again to Gernika, in Vizcaya and to the locality of Astigarraga in Guipúzcoa. I stopped in Bilbao before travelling to the city of San Sebastián and then on to the town of Biarritz in the Basque part of France, before returning to London.

Not far from Gernika, I visited the caserío of my friend Luisa Aulestia. Talking to Luisa, I realised that even if life in the Basque caserío has changed dramatically since I first met her in the 1980s, she was still in charge of the house, the kitchen, the chickens, a few ducks and the two pigs while her husband still cooks in the local txokos from time to time.

In Luisa’s vegetable garden, which is her pride and joy, she plants black and white beans, climbing towards the sun, supported not by bean poles but by sweetcorn/maize plants, as the Aztecs and Mayas did centuries before her. She is still growing her potatoes and amazingly large cabbages, which she calls berza. In the right season, bottling tomatoes and drying peppers and chillies/chiles has always been a priority for Luisa. She hangs red choricero and hot guindilla peppers from the windows to dry and bottles the fresh green piparras chillies, which all the family love. Come autumn/fall, from the apple orchards that surround the house, her husband and son make their own cider, which I was delighted to taste before lunch. She served alubias negras de Tolosa (black bean stew with black pudding/blood sausage and cabbage), accompanied by a small plate of piparras and, as is the custom, a glass of red wine from the Rioja Alavesa, an area of wine production inside Euskadi.

The following day, as I travelled towards the border with France, I stopped first in Astigarraga at the sidreras (cider house) of another friend, Rosario, whose recipes I love to cook. Astigarraga is a town in Guipúzcoa, well known for cider and cider houses. As I arrived, Rosario was upstairs in the main kitchen preparing one of her renowned tortillas de bacalao (omelette with salted cod) with properly desalted fish, large spring onions/scallions and green (bell) peppers, while her brother was already downstairs grilling the chuletas (T-bone steaks) in front of diners.

On the move again, I reached the ever charming San Sebastián where I found accommodation not far from the popular La Parte Vieja in the heart of the city. From eleven o’clock every day, La Parte Vieja is full of locals and tourists enjoying a pintxo, a little dish with the tastiest tomatoes or a wonderful plate of mushrooms. Mmm… My mouth is watering just remembering this scene. Walking down the streets, I could see the open front door of one of the best-known txokos in town. I could not resist stopping and sneaking into the main room, which was empty. I knew that come lunch or dinner time, a number of friends (usually all male members of the gastronomic society) would be sitting, waiting for the one member who had been cooking for hours during the morning to serve the food, possibly arroz con almejas (rice with clams) and merluza en salsa verde (hake in parsley sauce) cooked in a cazuela (earthenware pot). Not so long ago, women were not allowed to enter these societies. Now things have changed somewhat. Women are now invited on certain days to join their husbands or friends for lunch or dinner, but they are still not allowed to cook. Gastronomic societies were created as male-only clubs, considered by their members as a refuge to cook and eat for their own pleasure and for that of other members, some of whom are acclaimed chefs. It is a space chefs can disappear to from time to time, where they can experience dishes closer to home cooking that they may never confess to in public!

Whether they have a Michelin star or not, in the whole of the Basque Country, chefs are rightly considered brilliant stars themselves. Around the city of San Sebastián, there are 16 restaurants with Michelin stars: Akelarre, Arzak and Martín Berasategui have three stars each, making this a great reason to spend my very last evening there. I sampled some truly wonderful dishes (too many to remember) that have earned this city its reputation as a world-acclaimed food paradise. So here I was, heading up to the Monte Igueldo where Akelarre looks down onto one of the most beautiful bays that I have ever seen. Chef Pedro Subijana, a brilliant chef who I was privileged to accompany during his visit to London in the 1980s, was still the chef patron in San Sebastián.

The following morning in Biarritz, across the border in France, I had time to stop at an excellent pâtisserie (pastry shop) to buy the classic gâteau Basque, filled with cherries, which I took back to London with me. Later, in a small restaurant close to the airport, not far from the sea and imposing Pyrenees, I had for lunch a full plate of ttoro, the famous Basque fish and shellfish stew. I knew I had to return to the Basque Country as soon as possible.

HOMEMADE BASIC STOCKS

Caldo de pollo

CHICKEN STOCK

The aroma of chicken stock brings back memories of my mother’s kitchen. The stock was used in so many dishes: soups, casseroles and croquetas (croquettes), which I am still making today. Here, I have included a simple stock recipe, yet to me, it is the most pure in taste; beautifully clear and with no unnecessary ingredients to hide behind. It is made with fresh chicken bones, vegetables, herbs, black peppercorns and plenty of water.

2 fresh chicken carcasses

2 carrots, peeled and roughly chopped

2 celery leaves

2–3 tablespoons apple cider vinegar

1 bouquet garni (made with parsley sprigs, thyme sprigs and 2 bay leaves)

7 whole black peppercorns

salt, to taste

MAKES 2 LITRES/QUARTS

Place all the ingredients (except the salt) in a large stock pot and pour over enough water to cover them completely. Place over a medium to high heat and bring to a rapid simmer. Skim off any foam that appears on the surface; keep doing this until the stock stays clear. Keeping the heat low, gently simmer the stock for about 3 hours or until reduced by one-third. Leave the stock to cool, then strain through a fine-mesh sieve/strainer. Adjust the seasoning with salt to taste. Use the quantity needed for your recipe, then you can store the remaining stock in the fridge for a few days or in the freezer in portions for up to 3 months.

Caldo de carne

MEAT STOCK

Home cooks can use ready-prepared, store-bought meat and bone stocks, but making a stock at home from fresh ingredients is an easy thing to do. Yes, it takes time, but the result is better for recipes and as has been demonstrated by dieticians as being much healthier.

1 kg/2¼ Ib. inexpensive cuts of meat, such as oxtail, beef shank or shin

2 kg/4½ Ib. fresh beef bones

1 onion, peeled and halved

2 carrots, peeIed and roughIy chopped

1 ceIery stick/rib

saIt, to taste

MAKES 2 LITRES/QUARTS

Place all the ingredients (except the salt) in a large stock pot and pour over 5 litres/quarts water to cover them completely. Place over a medium to high heat and bring to a boil. Skim off any foam that appears on the surface; keep doing this until the stock stays clear. Keeping the heat low, gently simmer the stock for at least 2½ hours or until reduced by at least half. Leave the stock to cool, then strain through a fine-mesh sieve/strainer. Adjust the seasoning with salt to taste. Use the quantity needed for your recipe, then you can store the stock in the fridge for a few days or in the freezer in portions for up to 3 months.

Caldo ligero de pescado

LIGHT FISH STOCK

This basic fish stock is so easy to make. I use this stock to prepare rice dishes, stews and soups.

2 tablespoons Spanish extra virgin olive oil

750 g/1 lb. 10 oz. white fish head and bones

2 carrots, peeled and roughly chopped

2 leeks, cleaned and roughly chopped

2 tomatoes, peeled and roughly chopped

2 teaspoons tomato purée/concentrated paste

2 teaspoons choricero pepper paste (or red pepper paste)

salt, to taste

MAKES 2 LITRES/QUARTS

Heat the oil in a large stock pot. Once hot, add the fish head and bones and sauté well. Add the remaining ingredients (except the salt) and sauté for 2–3 minutes. Pour over 3 litres/quarts water, place over a medium to high heat and bring to a boil. Skim off any foam that appears on the surface; keep doing this until the stock stays clear. Keeping the heat low, gently simmer the stock for at least 30 minutes or until reduced by one-third. Leave the stock to cool, then strain through a fine-mesh sieve/strainer. Adjust the seasoning with salt to taste. Use the quantity needed for your recipe, then you can store the stock in the fridge for a few days or in the freezer in portions for up to 2 months.

PINTXOS

Small & delicious bite-size snacks

Pintxos: A way of living

Even if they appear to be similar in some respects, a pintxo is neither a tapa nor a ración, which is a larger portion of a tapa. Both tapas and pintxos are associated with an informal way of eating while drinking wine or beer in bars and restaurants. Tapa comes from tapar, the verb meaning ‘to cover’ that was originally used in Andalucía. A glass of Fino or Manzanilla sherry would be covered with something delicious, such as a small slice of Serrano ham. Pintxo is a Basque word derived from the Castilian pinchar, meaning ‘to prick’. In general terms, pintxo is the name given in the Basque Country to a small portion of food skewered on a wooden cocktail stick/toothpick. Nowadays, pintxos have become much more complex than that.

Pintxos are a constantly evolving, original food adventure prepared in a variety of shapes and sizes using an array of quality ingredients. They are presented in the most attractive way imaginable, visibly displayed on counters to attract passers-by. Even if many pintxo shapes appear to be similar, their diversity is astonishing. Some are prepared on slices of the local bread, while others are offered in pastry cases known as tartaletas (tartlets). You can also find medias noches (midnight buns), which are small, slightly sweet buns filled with cheese and smoked ham or other delights. Equally good are the family of minute sweet and salty croissants, which I love. Some pintxos are held together by a cocktail stick, some others are not, and the variety is growing by the day. On my last visit to San Sebastián, in a popular modern bar, I had a spectacular small plate of rice cooked to complete perfection. It was prepared with a clam sauce so delicious that I felt compelled to ask for a second helping. I was determined not to leave a single grain behind.

Perhaps surprisingly, some pintxos are now quite sweet. At La Viña, the renowned bar in San Sebastián, they offer as a pintxo a piece of the iconic burnt cheesecake that has made this bar one of the most popular in the old city. Foreign visitors adore it.

Many pintxos are prepared in advance, but never too long beforehand. Freshness is paramount. For me, it is the hot pintxo made on demand that I have become fascinated by, perhaps not surprisingly. Today more than ever, healthy competition encourages chefs to dedicate their professional lives to what has become the amazing cocina Vasca en miniatura (Basque cuisine in miniature).

Of course, we are talking about the Basque Country here. Since the 1980s, the innovation and creativity in Spanish food, and the influence of the dishes prepared by talented Basque chefs of all ages, has revolutionised bars and restaurants not only in San Sebastián, birthplace of the pintxo, but all over the Basque Country and the rest of Spain.

While socialising in bars, Basques drink cider and beer. They drink red wine mostly from Rioja and Navarra and, of course, the delightfully fresh and slightly acidic txakoli white wine produced in the areas of Orduña and Orozko in Vizcaya and on the hilly slopes of Getaria, in Guipúzcoa.

La Viña in San Sebastián

temping pintxos on a counter

La Concha, an iconic Basque beach

vines near Artomaña

Plaza de la Constitución, San Sebastián.

Txakoli vineyards overlooking the Cantabrian Sea in Getaria.

Gildas y piparras

ANCHOVY, OLIVE & PIPARRAS CHILLI SKEWERS

The original Gilda – one of the most popular pintxos – is a banderilla, the Castilian name given to a wooden cocktail stick/toothpick used to spear various ingredients. Gildas have only three elements: anchovies, green olives and piparras (moderately hot preserved green chillies/chiles). The anchovies used in Gildas are cured in salt, rinsed, covered in olive oil and then canned. They are pure umami.

Today, Gildas are found in many bars all over the Basque Country, but it is Casa Vallés, a classic bar in San Sebastián, where it is believed that this delicious banderilla was first created in the 1970s. Apparently it was to celebrate the film Gilda, which was showing at local cinemas at the time.

In the last few years, bars have been serving fresh piparras from June to October. Fried in plenty of olive oil until tender and sprinkled with coarse sea salt, they are served piping hot. On their own, piparras are simply wonderful.

12 good-quality anchovy fillets canned in olive oil (see note below)

12 green olives (see note below), stoned/pitted

12 piparras chillies/chiles (see note below), halved

12 wooden cocktail sticks/toothpicks

MAKES 12

Thread one end of an anchovy fillet onto a cocktail stick/toothpick. Next, spear an olive with the stick, followed by a piece or two of piparra. Pass the stick through the other end of the anchovy fillet to secure, wrapping the anchovy around the other ingredients. Repeat with all the remaining anchovies, olives and piparras to make 12 skewers.

NOTES

» Cantabria and the Basque Country produce excellent anchovies. They are expensive but their unique taste (umami at its best) makes them irresistible.

» I love Andalucian Gordal olives, which are fat green ones. I often marinate them in olive oil with lemon zest and rosemary sprigs.

» Piparras are a type of Basque green chilli/chile of moderate heat, which are preserved in vinegar and water with salt.

Tartaletas con bechamel de setas, chalotes y langostinos

CEP & SHALLOT TARTLETS WITH PRAWNS

Tartaletas are tartlets – small pastry cases filled with an assortment of ingredients, including ensaladilla de siempre (see page 45) and smoked salmon, often in a bechamel sauce. They are normally prepared as part of a canapé tray to serve on Christmas Day or at other festivities, but they are also popular as a traditional pintxo enjoyed any day of the year.

I love to use ceps. They are expensive but quite unique. Other types of mushrooms will also do very well, though the texture and flavour of the cep is difficult to surpass.

TARTLET PASTRY CASES

240 g/1¾ cups plain/all-purpose flour

30 g/⅓ cup ground almonds

20 g/¾ oz. icing/confectioner’s sugar

120 g/½ cup cold unsalted butter

2 g/½ teaspoon salt

1 medium/US large egg

CEP & SHALLOT FILLING

45 g/3 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 or 2 shallots, peeled and finely chopped

1 large cep, cleaned and thinly sliced

2 tablespoons plain/all-purpose flour

400 ml/1¾ cups full-fat/whole milk, or as needed

pinch of freshly grated nutmeg

salt and ground white pepper

TO FINISH

1 tablespoon olive oil

12 raw prawns/shrimp, deveined and peeled

pinch of finely chopped flat-leaf parsley

12 individual tartlet tins, 6 cm/2½ inches diameter, 3 cm/1¼ inches deep

8-cm/3-inch round cookie cutter

MAKES 12

First, prepare the pastry. Place all the ingredients (except the egg), in the bowl of a food processor and mix on a medium speed. When the texture is grainy (this will take around 4 minutes), gradually add the egg. Continue mixing at the same speed until all the ingredients are fully incorporated and have formed a soft dough that does not stick to the sides of the bowl.

Place the dough on a clean work surface. Using your palms and fingers, gently form it into a ball and flatten slightly. Cover the dough with cling film/plastic wrap and pat into a square shape (this makes rolling out easier). Chill in the fridge for at least 30 minutes.

Preheat the oven to 160°C/140°C fan/325°F/Gas 3.

Unwrap the dough and cut it into two equal pieces. Place one of the halves back in the fridge. Using the other half, place the dough on a rectangular sheet of parchment paper and cover with a second sheet. Gently roll out the dough between the sheets to a thickness of about 3 mm/⅛ inch. Using the cookie cutter, punch out 6 rounds. (Gather up any excess pastry scraps, mould into a ball, wrap in cling film and store in the freezer to use later for another recipe.)

Place one pastry round inside each tartlet tin. Using the tips of your fingers, gently press the pastry into the shape of each tin, making sure the dough reaches right to the top of the mould. Using a small fork, prick all over the base of each pastry case. Place the lined tartlet tins in the fridge to chill. Repeat with the second piece of pastry dough.

Place the lined tartlet tins in the preheated oven and cook for 20 minutes or until lightly golden. Remove from the oven and leave to cool completely before removing the pastry cases from the tins.

While the pastry cases are cooking, prepare the filling. Melt the butter in a saucepan, then add the shallots and sauté until translucent. Add the cep slices and sauté until all the moisture has evaporated, they are tender and have taken on a little colour. You may need to add a little more butter.