28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

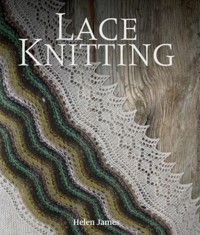

Knitted lace is beautiful, ethereal and eminently achievable by any competent knitter. Written by a passionate lace knitter, this comprehensive book contains a brief history of lace knitting and considers the similarities between the genre from different traditions. Whilst using traditional motifs, Lace Knitting moves away from the traditional square shawls of the past and focuses on wedding wraps, scarves and throws, as well as household furnishings such as cushion covers. This book is beautifully illustrated and includes a brief history of lace knitting; information about yarns, tools and techniques and a fully illustrated stitchionary, with charts and written instructions. There is information on techniques, with over seventy lace motifs and embellishments including making bobbles, beading and how to create the Estonian Nupp. It also includes seven straightforward, but effective projects, all of which can be varied and made more or less complex by the knitter. It is exquisitely illustrated with 227 colour photographs and 76 line artworks. Helen James is an experienced knitter and has had a life-long love of lace and lace knitting.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 203

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019