22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

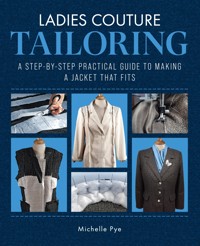

In this practical guide, Michelle Pye demystifies the process of making a handmade jacket. As an experienced bespoke tailor and teacher, she explains each step of the process from making a toile for fitting, cutting out, inserting the pockets, the application of the sleeves and collar, through to hand finishing and pressing the jacket. Much emphasis is placed on the preparation stage and then the alteration steps to ensure you get a fantastic fit. As well as explaining tailoring terms, Ladies Couture Tailoring warns of common mistakes and describes the techniques of the trade – such as using a clapper to absorb steam or shrinking out fullness to make the sleeve easier to put in – so you can enjoy making your jacket as much as wearing it. It is a rare opportunity to learn from an experienced tailor keen to share her skills and advise you throughout with her personal tips.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 272

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© Michelle Pye 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 917 4

Cover design: Sergey Tsvetkov

Photographs by Michelle Pye and Wendy Pye.

All products used in this book werepurchased from:English Couture Company18 The GreenSystonLeicestershireLE7 1HQwww.englishcouture.co.uk

Dedication

This book is dedicated to my late parents, Jack (John) and Iris Pye. Without their amazing support throughout the years I would not be where I am today. Secondly, it is dedicated to my sister Wendy. Without her unending patience and organizational and photographic skills, this book would never have been finished.

Contents

Introduction

01 Equipment and Materials

02 Choosing the Pattern and Fitting with the Toile

03 Pattern Alterations

04 Cutting Out

05 Joining the Pieces

06 The Pockets

07 The Foundations of the Jacket

08 The Collar

09 The Sleeves

10 Hand-Finishing

11 Pressing Off and Final Touches

Appendix

Glossary of Tailoring Terms

Index

Introduction

‘Tailoring is an art but it’s also a dying trade.’ Those were the words of a local tailor to my mother when she told him that I had a job in a tailor’s workroom in my home town of Leicester.

He was partly right, of course; tailoring is an art, and a properly tailored jacket is something quite beautiful. I have a theory about the second part of his statement. Tailors are very secretive people and will not pass on their skills willingly. Only the people working in their workroom will be privileged to any information and even then, only the bits they need to complete their jobs. Tailors also try to make things extremely complicated to the outside world, so people think it’s too hard and give up before they get the chance to give it a go.

The way fashion has gone recently doesn’t help either. There are fewer and fewer reasons to wear tailored clothes, but I always feel so good when I’m wearing a jacket or coat that I have made. I enjoy every minute spent sewing a jacket or coat, even the boring but vital fitting stages. The satisfaction of saying ‘I made it’ when someone asks, ‘Where did you get that jacket?’ is second to none.

The most common question I’m asked is, ‘What is the difference between a dressmaker and a tailor?’

•A dressmaker will sew together the pieces of fabric and trust the pattern will create the shape.

•A tailor will cut the pattern pieces from the fabric and mould them to the shape required.

There are many ways to tailor a jacket and if you went into each tailor’s shop on Savile Row in London, you would come across many ways of doing the same thing. Each tailor would swear his method is the only way of doing it.

This book contains the methods I learnt in my seven years in a gentlemen’s tailoring workroom and the adaptions I have made to that method whilst making for my mainly female customers and teaching students. I have broken down each stage into easy bite-size pieces, so everyone who has dressmaking skills can have a go and make a perfectly wearable jacket.

I know that it will fit you better and be made of a better-quality fabric and that the making-up will be of a higher standard than anything you will buy in the shops.

Another question I’m asked is, ‘How long does it take to make a jacket?’ Unless you are working in the workrooms with a deadline over you, I usually say, ‘I love every minute I spend tailoring so enjoy it, however long it takes.’

I hope this book will inspire you to have a go at making a jacket and that it gives you as much enjoyment as I have every time I make and wear a handmade jacket.

Note 1:

I have given the measurements in this book in both metric and imperial. The conversion of these measurements is not precise. You can use either system of measurement but don’t start out using one system and move to the other or your measurements won’t be accurate.

Note 2: Instructions are for right-handed readers but with extra information for left-handed ones. If you are left-handed it may sometimes be helpful to hold the illustration up to a mirror to check what you are doing.

Chapter 1

Equipment and Materials

I have listed the equipment I use for tailoring, some of which you will already have for dressmaking projects. You can tailor quite successfully if you have, for instance, different pins or needles, but I find the items listed make things easier.

Equipment

I use extra-long extra-fine pins for all my sewing; they can be used with most weights of fabric. With a medium-weight tailoring cloth they are perfect, as the points are very sharp and glide through the fabric when pinning on the pattern, and the extra length of the pins enables you to easily pin enough fabric to secure your seams when sewing.

Pins and needles.

Betweens needles are known as tailors’ needles. They are noticeably short; some are only about 3.1cm (1¼in) long. A tailor likes to use these needles as the thimble used has no end in it (see below); with this type of short needle, you don’t have to bend your finger back as far to push it through as you would with a normal-length needle.

Have a go with these needles before you dismiss them. Many of my students have been initially very way of using needles this small but, after trying them out, have switched to them and won’t use anything else.

I use a tailor’s thimble; this type has no top on it. This is because a tailor doesn’t push the needle through with the top of the finger but with the side of it. You push the needle through the cloth using the area close to your nail, thus using the strongest part of the finger.

Thimbles.

Many of my students say they can’t use a thimble. As soon as the thimble goes onto the middle finger, they automatically use another one for sewing. The way I was taught to get used to sewing with a thimble was to get a big piece of canvas with a couple of layers of padding placed on top of it; I was then shown how to pad stitch. I covered the entire piece of canvas with small stitches all the way across it, forcing myself to use the thimble. If you do this for a couple of hours, using the thimble becomes second nature; I can’t sew without one now. If you don’t use a thimble and you do a lot of tailoring, you will get a very sore finger.

Before thimbles were invented, apprentice tailors were encouraged to do a great deal of sewing to make their fingers bleed – without getting any blood on the garment they were creating, of course. The finger would then scab over. After doing this for about six months a callus would form, producing a built-in thimble! This is a very painful way of acquiring a thimble and I definitely wouldn’t recommend it.

PRICKING YOUR FINGER

Should you be unfortunate enough to get blood on your sewing, whether it is a jacket or anything else, simply get a length of thread (I like to use basting thread), put it into your mouth and moisten it. Now take the thread and rub it onto the blood stain. It has to be saliva; both blood and saliva have enzymes in them and they work together to lift the blood stain from the fabric.

In a tailoring workroom you rarely see anything other than large shears, somewhere between 20cm (8in) and 30cm (12in) with metal handles. I tend to use 23cm (9in) or 25cm (10in) as my hand aches from the weight of anything bigger. You can get shears up to about 40cm (16in).

Shears.

I only use my best shears for cutting fabric and I am extremely careful not to drop them.

Use an old pair of shears for cutting pattern paper, otherwise your fabric shears will become blunted and not cut smoothly.

There is the age-old problem of family members borrowing your shears but be very firm about this. I’ve heard of various methods of controlling such borrowing: the best one I’ve heard is to use a padlock on the handles!

Tailor’s chalk will mark most fabrics. I only use white chalk as there is more chance of it brushing off than if you use coloured chalk. I even use it on white or cream fabrics.

Tailor’s chalk.

There are many different pens and pencils on the market claiming to do the same job. I only use Hancock’s chalk as it contains no wax. Some brands do contain wax and on some fabrics it will stain.

USING TAILOR’S CHALK

Always test the chalk on a spare piece of your fabric before you start, then you can be sure it will brush off without leaving any residue. Always use a sharp piece, so that the line drawn is fine and sharp. Using blunt chalk will give a very thick line and can make markings inaccurate.

You can sharpen your chalk using a pair of scissors (the paper-cutting ones, not the fabric-cutting ones). Be careful if you do this; I only use this method if the chalk sharpener isn’t available. A safer way to do this is to use a chalk sharpening box.

A chalk sharpening box has blades set at an angle. To use it you just rub the chalk across the blades on both sides of the chalk; this leaves a very sharp edge, perfect for drawing precise lines on your fabric.

Chalk sharpening box.

The box in the photo was made for me by a retired tailor, more years ago than I care to admit, and is made from mahogany, but you can get a plastic version. The box will give you a beautifully sharp edge to your chalk with little effort.

The point presser and clapper is a useful piece of equipment. The clapper or banger is the bottom of the wooden block. When you press a seam or the edge of your jacket you place the clapper on it and it absorbs the steam: this sets the edge immediately, meaning that the fabric won’t rise up and give a half-pressed look.

Point presser and clapper.

Despite its name you don’t have to apply a lot of pressure to make it work. I find a tailor’s ham invaluable when making jackets of any sort as it provides a series of curves, some more curvy than others. By using the shape of this ham inside your jacket you can make pressing curves easy without creasing the fabric on either side of the seam you are pressing.

Tailor’s ham.

Used in conjunction with the point presser the ham will get a perfect finish for your rounded seams every time you press.

A sleeve roll is a useful piece of equipment when pressing sleeve seams open because you don’t want to put creases into the sleeve whilst pressing open the sleeve’s second seam. I prefer this roll to a sleeve board, as you can accidentally press an impression of the edges of a sleeve board onto the sleeve, leaving creases in it.

Sleeve roll.

It isn’t easy to press a sleeve once it’s joined up and getting rid of extra creases or impressions just adds to the problem.

Your iron needs to become like a friend to you. When tailoring you do need steam and heat to successfully press and shape your jacket. I prefer to use a steam generator iron: this type of iron only produces steam when you press the button, so you will be able to control exactly when and where the steam is applied. This also means that if you don’t want to use steam for the seam you are pressing, you don’t have to.

An ordinary iron only delivers steam every now and again, so it may well take a bit longer to do the pressing stages.

You can also use a dry iron and a wet cloth but again this takes more time. If you are using a wet cloth, be careful not to get it too wet as water can mark certain cloths.

As my pressing cloth I always use a piece of silk organza. This fabric is sheer so you can see through it, enabling you to keep your eye on what you are pressing and you don’t press any creases into your sewing by accident. Silk organza is a tough fabric and I promise it won’t melt when you use a hot iron on it.

Pressing cloth.

I never finish off the edges of my silk organza pressing cloth, as making a hem or overlocking the edges creates a bulky finish. If you catch this as you are pressing it could leave a mark on the fabric you are pressing. Just trim off the fraying ends as they appear, and after a while the cloth stops fraying. I also wash my cloth when it gets dirty; this does take some of the dressing out of it, but it prolongs the life of the cloth.

A tracing wheel is a useful tool to transfer all the pattern markings to the redrafted dot-and-cross paper pattern once all the fitting stages have been done. Using the wheel means you don’t have to lift the pattern out of the way to transfer the markings, which makes it more accurate.

Tracing wheel.

It works best if you put a piece of fabric or a pressing board underneath it. You will have to press quite hard to get the wheel to mark the paper if you just put the pattern onto the work surface. However, be careful if you are using a tracing wheel on a polished table: if you press too hard the spikes on the wheel will damage the surface of the table.

Once you have all the markings traced onto the pattern, you can use a pen or pencil to go over them and mark them clearly.

The hole punch is used when hand-finishing. It makes a small hole in the fabric at the end of the buttonhole nearest to the front of the jacket so that the shank of the button can sit comfortably without puckering or distorting the fabric. This punch has several sizes of hole to choose from but you always use the smallest one for buttonholes.

Hole punch.

For patterns I use dot-and-cross paper, as it is stronger than the traditional tissue paper. When I buy a commercial pattern, I trace it out onto the dot-and-cross paper and keep the original pattern for reference only. When making alterations you can stick clear adhesive tape (such as Sellotape) to this paper without creating a problem whereas tissue paper does not take kindly to having lots of tape stuck to it. It can also crease and not sit correctly once the tape is applied; this can cause you to make an inaccurate alteration to your pattern which will then alter the fit of the jacket.

Dot-and-cross paper.

I always have a ruler to hand. I use it for altering patterns and for marking cloth using tailor’s chalk. I use the one in the photograph, which came from the workroom I was trained in. The end of it has a metal strip, which is a reinforcement to stop the end wearing out. The measurements start right at the end of the ruler, not slightly in, as most of the rulers on the market do.

Ruler.

I’m told that it is more like a ruler used by a carpenter; these are available from DIY stores. I find the 45cm (18in) ruler is more useful than one of 30cm (12in) (too short) or one of 60cm (24in) (too long).

I always use inches for my measurements, but you don’t have to if you want to use metric measurements – that’s fine. I have put the measurements in both throughout the book, but the conversion isn’t exact, so don’t start out using one set of measurements and switch halfway through.

When you are tailoring you don’t need a sewing machine which does dozens of different stitches. What you do need is a machine which can take heavier-weight fabrics and apply a straight stitch and a basic zigzag stitch.

I love sewing machines, from the basic straight stitch machines to the most complex computerized ones. I’m the first one to jump on a machine and try it out.

Although I have said that you don’t need a complicated machine for tailoring, some of the more complex machines are easy to work with and have a lot of time-saving gadgets, for example a thread-cutting button.

This book is not an excuse for buying a new machine; however, if you get a good deal on one, why not treat yourself!

Basting thread is a special cotton thread made to break easily. It has a slightly rougher texture than a normal thread. This is one item I can’t sew without.

Basting thread.

Doing tailor tacks is so simple with this thread, as the rough texture of the thread keeps the tailor tack in place.

I also use this thread when putting in temporary basting stitches which hold layers of fabrics together whilst more permanent stitches are put in place. Basting thread is perfect when pulling out the basting stiches right at the end of the making-up process. Should it get caught when you are pulling it out, it snaps, unlike ordinary thread which would cut into the fabric.

USING BASTING THREAD

When I’m using this thread, I don’t cut the end of it, I break it. The thread is quite thick and if you cut it, it’s almost impossible to thread the needle. If you break the thread, it leaves a wispy end, which is finer and more easily pushed through the needle.

I use beeswax to strengthen the thread when I’m hand-working buttonholes. You pull the thread through the wax, then take it to the iron. Make sure you have a piece of scrap fabric on the ironing board. Place the thread onto the scrap fabric and fold the fabric over, place the hot iron gently on top and then pull the thread through. This will remove any excess wax before you start the buttonhole. The wax will then not get on to the ironing board or the iron and then transfer to your jacket when you press it. This process leaves enough wax on the thread to strengthen it but not enough to stain the front when you press the finished buttonhole.

Beeswax, buttonhole thread and buttonhole gimp.

The piece of beeswax you can see in the photograph was given to me by my grandfather when I started tailoring. He used to work in the shoe industry and used this piece of wax in his work.

You can buy special heavyweight thread to work buttonholes with: in the trade it’s known as buttonhole twist. If you can’t get hold of this thread, then use a topstitching thread (a slightly thicker thread) which is readily available in most stores where you buy ordinary cotton threads. There is a good choice of colours in topstitching thread, which is a good thing as women’s jackets come in a bigger variety of colours than men’s. Traditional buttonhole thread comes in an very limited choice of colours.

Buttonhole gimp is a thick thread which is placed onto the edge of the buttonhole and the buttonhole stitch is then worked over it. This gives a rounded, slightly padded shape to the edge of your buttonhole.

The thread is made up of several core threads, with an outside lighter thread wrapped around the core. It has almost a wire-like feel to it. If you can’t get hold of any gimp, you can use several strands of the topstitching thread instead; these strands can be waxed to make them stronger.

Materials

Most people think that when you sew anything you just need the fabric and perhaps a lining, if needed.

The list of fabrics here looks like quite a long one. This is an extra expense, on top of your fabric and lining, so why are they all necessary?

Creating a jacket is not like sewing anything else. You need some support inside the jacket to help to keep its shape and this is done by a variety of materials. The main canvasses will be shaped for what is known as the T-zone. Basically, this supports the front of the jacket, the front edge where the buttonholes will be, and up through the lapels and into the collar. It also supports the sleeves into the armhole.

The under collar will need its own interfacing to support the top collar as well. I will be explaining how to cut and use these different interfacings as we go along.

The following are the fabrics I have used whilst making the jacket featured.

Fabric for the jacket

Traditional tailoring is time-consuming as there is a lot of hand-stitching to do: I always use a mediumweight pure wool fabric. It’s not worth doing this method on a cheap fabric.

Fabrics for inside the jacket.

I expect my jackets to last for as long as possible – at least ten years, maybe twenty.

This is possible, providing you don’t change shape, of course. A cheap, polyester fabric will start looking out of shape within a few wearings of the jacket.

I like to use an acetate lining if possible. I’m a big fan of patterned lining but if I can’t get that, then a satin lining always looks beautiful.

Jacket lining is usually a bit heavier than the lining you would use in dressmaking.

You can always decorate the lining yourself if you can’t get a patterned one you like. (SeeChapter 5 for details.)

For a woman’s jacket I use a lightweight tailoring canvas. You can get heavier weights than I use but I find that the wearers usually prefer the jacket not to be too stiff and heavy. This fabric will form the base layer of interfacing for the T-zone.

A heavy chest canvas is used for the base of the chest piece or plastron (see Chapter 7 for details). This canvas will spring back to shape if it’s squashed whilst you are wearing the jacket; for instance, if you put a handbag on your shoulder or put on a seat belt in the car.

A soft domette is used for the top part of the chest piece or plastron. This is to add a layer of padding to the plastron and to stop the rougher texture of the chest canvas from coming through to the lining.

I like to use a lining for my pocket bags, but you can use a cotton pocketing (the best-known variety of which is called silesia) for this. It is quite tightly woven and is therefore stronger and longer-lasting than ordinary lining.

Usually I only put tissues into my jacket pockets. If you are intending to use them for other, heavier things or more often, then the cotton pocketing would definitely be preferable to ordinary lining.

Duck linen is a lighter-weight canvas I like to use for the collar of a lady’s jacket as traditional collar canvas can be a bit too stiff.

This interfacing is hand-padded to the under collar to create the shape; the top collar then becomes just a decoration to cover up the workings underneath.

I use a pure cotton lawn to give some support to the lapel whilst pad stitching. The nature of the cutting of a jacket means that the main fabric and the canvas are slightly off-grain where the break line is positioned. If the break line were cut on the straight grain, the front edge would be off-grain, causing a lot of problems with the hang of the jacket.

By cutting this piece of fabric on the straight grain, it stops the main fabric and the canvas from stretching out too much, whilst still allowing for the shaping of the lapel.

Volume fleece is a wadding fabric used in the head of the sleeve to pad out the gap between the head of the sleeve and the armhole of the jacket, giving a generous, rounded appearance to the crown of the sleeve.

In traditional tailoring a sleeve head is usually used but I find that they can prove a bit bulky for ladies’ tailoring. I prefer how the volume fleece creates a padded roll for the shoulder pads to sit on but, depending on the style, you could use a sleeve head as well or instead of the volume fleece.

I use an off-grain edge tape for the edges of the jacket: this is a fusible tape cut at about 13 degrees off straight grain.

Edge tape.

This degree of stretch enables you to go around a shaped edge but still provides the stability of a stay tape.

I use this tape on the front edge of the jacket and then it is hand-stitched to the canvas.

Traditionally a non-fusible wide linen stay tape is hand-stitched to the edge, but again I find this makes a bulky edge, far too heavy for a woman’s jacket.

Shoulder pads.

I use felt shoulder pads in my jackets. These pads don’t compress down when you stitch them in, unlike the foam ones. Nor do they disintegrate over time like the foam pads tend to do. They are not too big and bulky, perfect for ladies’ tailoring.

Hand Stitches

When I’m hand-stitching anything, I always use thread which is cut the length of my arm. When this length is threaded through the needle it means that you will always be able to pull the thread straight through in one movement and not have to go back and tug the last bit of thread through. Some of my students like to cut exceptionally long lengths of thread so they won’t have to thread the needle twice. This wastes a lot of time when you are hand-stitching, and the thread may break or get twisted as you stitch.

I’ve used a white thread in the following photographs where appropriate, so you can see the stitches.

I use slip stitch for hems or any invisible stitching inside the jacket. This stitch can be done in two ways, depending on which part of the jacket you are stitching. For the hemline you fold back the edge of the hem. If you are stitching any other part of the jacket, you keep the edges flat and sew over them.

Slip stitching a hem, step 1.

Slip stitching a hem, step 2.

Slip stitch for other areas.

To slip stitch a hem, first baste the hemline in place. Turn back about 6mm (¼in) of the hem, leaving you with a fold near the edge of the hem.

Then, using a single thread of the cotton you are using to sew the jacket, pick up a single thread of fabric from the jacket and a stitch from the folded hem. The stitches need to be about 1.3mm (½in) apart and are worked towards you.

If you take a small enough stitch in the main fabric, the hemming will be invisible on the right side. Once you have completed the stitching, fold the hem back up. Your stitching will then be underneath the hem and it will be almost impossible to catch and pull it.

To slip stitch areas other than a hem, again use the cotton being used for the main fabric. Slip the needle under the edge to be fastened.

Bring the needle over the edge of the seamline and take a stitch into the fabric you are fastening it to, and back into the seamline.

The stitches can be quite large, about 2cm (¾in). For the picture I have used a white thread so that it is easier to see the stitches.

Make sure that you only stitch through the two layers of fabric you are fastening; don’t go through to the right side of the fabric.

As with the previous version of this stitch it is worked towards you.

Basting is the tailor’s word for tacking. Most basting stitches are only temporary, put in to hold some part of the jacket whilst you put more permanent stitches in place.

Basting.

Basting stitches are usually quite large, up to 7cm (3in) long but dipping through the layers for a much shorter distance, all using a single thread. I always use a knot at the end of the thread; it is easier to pull out basting if you can pull the knot.

Some of the basting threads do stay in the jacket permanently; they will be inside the jacket, so no one will be able to see them.

When I get to the end of the row of basting, I put in a back stitch to secure the end and then, using my thumbnail on the cotton, just snap it off: it’s much quicker than using scissors. This trick only works with basting thread; please don’t try it on ordinary thread as you will probably end up cutting into the cloth or ruining your nails.

Thread tracing It is similar to basting but the surface stitches are smaller, about 2.5cm (1in), and the pick-up stitches are considerably smaller. A thread-traced line should look like an almost continuous length of thread. Thread tracing is usually used to mark an area ready for either pressing or stitching.

Thread tracing.

Prick stitching is a topstitch used on pockets or to hold the edge of the jacket. It is worked from right to left (but from left to right if you are left-handed). Use a single thread of ordinary cotton (although you can use a thicker, topstitching thread to give a more prominent stitch) and bring the needle to the right side of the jacket.

Prick stitch, step 1.

Prick stitch, step 2.

Now do a tiny backstitch, usually over a couple of threads. Come out of the cloth about 6mm (¼in) further along the piece. By using such a small stitch, you will only see a tiny dot of a stitch forming on the right side, hence the name prick stitch.

If you are topstitching the edges of a jacket, you can work either directly on the edge of the cloth or 6mm (¼in) in from the edge: this all depends on the effect you wish to create. The former makes the stitching almost invisible; the latter makes it more decorative.

Felling is used to secure the lining hem of the jacket or sleeve. Like slip stitching it can be worked on the edge of the fabric or with the fabric folded back. If you do it with the edge folded back the stitches will be invisible once the edge is put back into its finished position.

Felling.

This stitch is worked from right to left (or the reverse if you are left-handed). Again, you need a single thread to work this stitch.

Fold back the hemline by putting your needle about halfway between the folded edge and the basting line. You can then separate the two layers of the folded hem.

Pull the top layer up and backwards to reveal a fold: this is where you will stitch.

Take a small amount of the cloth from the main fabric, making sure you are not going through to the right side of the jacket, then a small amount from the folded-back edge.

Once you have stitched the hem, smooth the top layer back down to cover the stitches.

The stitch length is a maximum of 6mm (¼in). These stitches are permanent and need to be very neat.

You can work this stitch in exactly the same way but not folding back the hemline, just using the folded edge of the hemline instead. I use the stitch this way when felling the edge of the lining at the bottom of the sleeve, stitching the lining for the armhole into place and finishing the edges of the welt pocket.

Pad stitching is a very clever stitch and can be sewn in two different ways. Whichever method you use, the stitch is worked in the same way, just held differently.

Pad stitching the plastron, step 1.

Pad stitching the plastron, step 2.

Pad stitching for plastron, step 3.

The first method is to use it flat on a table to hold layers of cloth together. (I use this for the layers of the plastron.) You are stitching three layers together, so keeping everything flat on the table will stop the layers moving whilst you are stitching.

I find it quicker if you use the table to bounce the needle off as you take a stitch. Be careful when doing this, as the needle pricks will mark the table below. Don’t do it if you are working on your polished dining table (I use a cutting table with a plywood finish to it).