Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Phillimore & Co Ltd

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: Phillimore Editions

- Sprache: Englisch

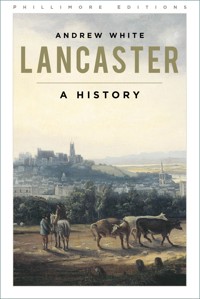

Lancaster, the county town of Lancashire, stands at the lowest bridging point of the River Lune. A chartered borough since 1193 and a city since 1937, it has had a long and turbulent history. Since the Roman army first saw the strategic possibilities of a low hill by the river it has housed garrisons and acted as a fortress. Its position on the main west-coast road to and from Scotland has on numerous occasions led to the passage of hostile armies. As county town and seat of the Assizes it has seen all the principal criminal cases for Lancashire tried in its magnificent Castle over the last eight centuries. Next to the Castle in a typical juxtaposition of Church and State stands the Priory church with its own history running back some twelve or thirteen centuries. In this book, based wherever possible on original sources, such as the rich resources of the borough records or the local newspapers, the author takes a thematic approach. In ten chapters he examines themes such as 'House and Home', 'Working for a Living' and 'Where do you come from?', the last of which is a study of all the people who over the centuries have come from other countries to live in Lancaster.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 353

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2003, this edition 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Andrew White, 2024

The right of Andrew White to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 569 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Introduction

One Where do you come from?

Two Development of the Townscape

Three House and Home

Four Lancaster on the Map

Five Working for a Living

Six Entertainment

Seven Getting There

Eight Alarums and Excursions

Nine Priory and Castle

Ten The Majesty of the Law

Notes

List of Illustrations

Frontispiece: ‘Engraving of Lancaster from the south east by W. Westall, 1829’.

1 The North East Prospect of Lancaster, 1728

2 Roman altars from Burrow-in-Lonsdale and Folly Farm

2a Tombstone of Insus

3 Drawing of the tombstone of Lucius Julius Apollinaris

4 Drawing of Roman bronze forceps

5 Anglo-Saxon Cross with a Latin inscription

6 Anglo-Saxon Cross with an inscription in Anglian runes

7 Grave of Sambo at Sunderland Point

8 Grave of John Dixon

9 Painting of ship being built at Brockbanks yard

10 Cartoon of German band from Punch magazine

11 Mosque in Fenton Street

12 Advertisement for Luneside Engineering, Halton, 1964

13 Fragment of the Wery Wall

14 Reconstruction of Roman Lancaster from the Moor

15 The Roman fort and distribution map of Roman finds

16 Marsh Enclosure, 1796

17 Location of main fields

18 Villas on the Greaves, from Harrison & Hall’s map of 1877

19 Anchor Lane under excavation, 1999

20 Aerial photo of Castle Hill, c.1973

21 Reconstruction of the Dominican Friary

22 A typical yard: Ross Yard off Cheapside

23 Excavation of 65 Church Street in 1973-4

24 Reconstruction of Sir Robert de Holand’s 1314 house

25 Detail of 1684 map – Great Bonifont Hall and Stewp Hall

26 Three of four pairs of re-used oak crucks found at Mitchell’s Brewery

27 View of Stonewell in 1810 by Gideon Yates

28 View of the Market Place c.1770

29 Seventeenth-century stone houses in Church Street

30 Drawing of Church Street with old houses surviving

31 Reed and plaster wall at 11 Chapel Street

32 Reconstruction of the building of St George’s Quay in 1751

33 Plan of lots for leasing in Dalton Square

34 Detail from Clark’s map of 1807

35 The Albert Terrace, East Road, seen from St Peter’s spire, c.1890

36 St George’s Quay terrace

37 Plan of area around Town Hall c.1910

38 Moorlands estate, seen c.1900 from the spire of St Peter’s

39 Council Houses, Denny Avenue, Ryelands, c.1932-3

40 Scale Hall developments, 1930s

41 Pre-fabs at Ashton Road

42 1960s high-rise at Skerton

43 Speed’s map of 1610

44 Map of 1684

45 Detail of Market Place from 1684 map

46 Map of 1778 by Stephen Mackreth

47 Binns’ map of 1821

48 Cartouche to Harrison & Hall’s map of 1877

49 Detail of Freehold Estate from Harrison & Hall 1877

50 Detail of the Military Barracks from Harrison & Hall 1877

51 John Lawson’s farthing token

52 Portrait of William Stout

53 Clay tobacco pipe with John Holland’s mark

54 Robert Gillow in the Freemen’s Rolls

55 Portrait of Dodshon Foster by William Tate

56 Handbill for Richard Dilworth, tallow-chandler

57 Centre of Moor Hospital

58 Handbill for Jane Noon

59 Watercolour of ‘Lancaster from the East’

60 Houses at Golgotha

61 A Victorian washerwoman, from Punch magazine

62 Thornfield, Ashton Road

63 The 1993 boundary walk

64 Theatre bill, 1772

65 The Circus comes to town in the 1890s

66 Pencil sketch of Mr Green’s balloon attempt, 1832

67 Racecourse on the Marsh, from Yates’ map of Lancashire, 1786

68 Handbill for a ‘long main’ of cocks

69 Detail of Mackreth’s map showing the bowling green at the Sun Inn

70 Portrait of S. Dawson, cycling pioneer

71 Williamson Park Cycling Club, c.1895

72 Scene from the Pageant, 1913

73 Roman roads in Lunesdale

74 Reconstruction of Cockersand Abbey by David Vale

75 Road map by Ogilby, 1698

76 Detail of coal cart and horses from a Wray estate map of 1773

77 Waterwitch II

78 Oversands travellers

79 Fowler Hill toll bar

80 Handbill for coaches running from the Old Sir Simon’s Inn

81 The old King’s Arms Inn

82 Drawing of the locomotive John O’Gaunt

83 Local cartoon of c.1842

84 Reconstruction of Penny Street station by David Vale

85 Battery bus in Market Square during the First World War

86 Single-deck Lancaster Corporation buses at Scotforth Square

87 The M6 motorway under construction, c.1959

88 Charter of 1193 and wrapper

89 Detail of Church Street from 1684 map

90 Fred Kirk Shaw’s pageant painting of Bonnie Prince Charlie

91 Reconstruction of a seventh-century chieftain’s house and church

92 Hubert Austin’s plan of discoveries in the Priory church, 1911

93 Reconstruction of the Priory in the twelfth century

94 Reconstruction of the Priory church in the late fifteenth century

95 Plan of the Priory church in 1819

96 Engraving of the Priory church looking east as it was in the 1840s

97 The medieval choirstalls

98 Engraving of the Priory church looking east in about 1864

99 Engraving of the Priory church after 1864

100 ‘Empty Stalls or The Mare and the Manger’ by Emily Sharpe

101 St Joseph’s Catholic church, Skerton

102 Reconstruction of Castle in Norman times by David Vale

103 Plan of Castle prior to 1788, with the names of towers. P. Lee

104 Interior of the Well Tower, showing a window seat

105 The great Gatehouse of the Castle

106 Vertue’s engraving after the 1562 drawing of Lancaster Castle

107 Watercolour by Thomas Hearne showing the rear of the Castle

108 Watercolour by Robert Freebairn showing the Shire Hall

109 Drawing by J.S. Slinger showing the lock-ups in the old Town Hall

110 The High Sheriff and javelin men ready to meet the Judge at the Castle

111 Title page of Potts’ ‘Wonderfull Discoverie’

112 Engraving of life in the debtors’ prison by Edward Slack, c.1836

113 ‘The Castle and Arrival of Prisoners’

114 Hanging Corner

115 Portrait of Rev. J. Rowley in 1856, aged 86

116 Bill for hanging John Heyes in 1834

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the help of a great many people in bringing this book to publication. First of all to Noel Osborne and the staff at Phillimore, who encouraged and assisted at every stage. Then my colleagues at Lancaster City Museums, especially Susan Ashworth, Paul Thompson, Ivan Frontani and Wendy Moore, for information and technical help with illustrations. Then there were the staffs at Lancaster Library, especially Jenny Loveridge and Susan Wilson, at the Lancashire Record Office, especially Bruce Jackson and Andrew Thynne, and at the Whitworth Art Gallery, especially Charles Nugent. I am most grateful to the late David Vale for his reconstruction drawings; those in this book and others are the fruit of a long collaboration between us at Lincoln and Lancaster. Deborah Dobby and Ruth Shaw are credited separately in sections for which their research was most helpful. I am also grateful to Dr Michael Winstanley and to other members of the Wray History Group for many useful insights, and to Mike Derbyshire for discussions on Lancaster’s fields.

In addition to the foregoing I would especially like to thank the late Bill Pearson, Town Clerk of Lancaster, and Charles Wilson, City Architect and later Town Clerk, not only for their help and encouragement but also for their work in the 1980s and 1990s in turning Lancaster into such a good place in which to live.

Finally I acknowledge the support and forbearance of my wife Janette as I headed off to my study each evening in the winter of 2001-2 to write the text, and again in 2023 to make various revisions.

Picture Acknowledgements

Nos. 16, 68, 80, 83 Lancaster Central Library; nos. 10, 61 Punch Magazine; no. 28 Whitworth Art Gallery; nos. 56, 58 Soulby Collection, Cumbria Record Office, Barrowin-Furness; no. 34 Binns’ Collection, Liverpool Library. All the remainder are courtesy of Lancaster City Museums.

Introduction

Today Lancaster has the dignity of a city. But this rank only dates from 1937, which surprises many people. Lancaster and York are often referred to together as historic cities, largely because of the mistaken view that the two medieval royal houses of Lancaster and York actually stemmed from those places. In truth the two could not be more different in origins. York was a Roman legionary fortress, a colony of Roman citizens and, later on, capital of one of the provinces of Britain. It became the seat of one of the two medieval archbishoprics in England, a walled city with a great minster church, and de facto medieval capital of the north. Lancaster was a Roman auxiliary fort with a cluster of civilian buildings around it which probably felt more like a village than a town. In the Middle Ages it had a single large parish church, not a cathedral, and no walls. It was the county town of a far-from-prosperous and thinly populated county and what power it had was mainly vested in the royal castle which dominated the town. Any resemblances between the two places are of more recent origin and little more than skin-deep.

I have not gone on at such length to do down the merits of Lancaster; it is a city of great charms and much historical interest. But it is as well to start out with a clear idea of what it is not, and why. The north west was until the Industrial Revolution a poor and often backward area. Its archaeological remains from almost every period before the eighteenth century are more exiguous than those of any comparable area on the east coast. In the Middle Ages the region could support only two cities, Chester and Carlisle. It lay close to the Scottish border and for centuries a very real threat hung over the region, breaking out at intervals into outright warfare and invasion. This in turn cast a blight over many material developments, such as architecture and agriculture. Great changes do not tend to occur under an ever-present threat of raid and ruin. Lancaster was for many centuries typical of its region, a modest town in a very modest environment. Only with the rise of overseas trade in the Georgian period did it make much of a mark. Even this was short-lived and eclipsed by the much greater rise of Liverpool, with which it competed as a port, and of Manchester as a great manufacturing town.

It has, however, a remarkable history and one which has been established in considerable detail. The town is of a manageable scale even today, and it has kept to a remarkable degree evidence of its early layout and topography, two factors alone which make it a rewarding place to study. Its position as county town and its possession of a significant royal castle have given it an importance beyond that to be predicted from its size in the medieval period. Its geographical location, so poorly placed for trade and influence when Europe was the main target, suddenly became a great advantage in the late seventeenth century following the opening up of trade with the West Indian and American colonies.

With the coming of the Industrial Revolution Lancashire, too, was suddenly catapulted into prominence. From being a poor and backward area the county rapidly grew to become one of the most densely-populated in western Europe. Unfortunately, institutions such as the law and the parochial systems failed to keep pace. Consequently the county overstretched the available resources. Its county town gained a huge accession of legal business at the Assizes held twice each year. While the failure of the parochial system here is less marked because of its widespread impact in the north, Lancaster still remains a good example of the huge undivided parishes left over from the Middle Ages to more expansive times.

1 The North East Prospect of Lancaster by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, 1728, one of a series illustrating all the major cities and county towns of England and Wales. The view takes in Skerton village, with its mill, to the right, the S-bend of the river Lune, and St Leonardgate, Moor Lane and Penny Street respectively to the left. In the foreground is the main reach of the river around Green Ayre, the open ground to the left of centre. In the centre are the Castle, still partially demilitarised after the Civil War and the Priory church still with its medieval tower. Below is the late medieval bridge and shipping. Despite the somewhat sketchy nature of the view and the conventionalised buildings, it seems quite accurate in its main details and equates well with the Towneley Hall map of 1684.

Because the town was on the main road to the north and was the seat of the Assizes it attracted a disproportionate number of visitors. From the eighteenth century this was enhanced by the growth of the Picturesque movement. Travellers to the Lake District from the south and east habitually used Lancaster as a stepping off point for the Lake District via Lancaster Sands, a route which had the sanction of no less a guide than Wordsworth.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Lancaster was often out of step with the rest of its county, experiencing boom when others experienced bust, and vice versa. Its industrial base was established later, and dependency on textiles only followed the decay of a mercantile empire. Its position as county town led to an accumulation of facilities here, some of which still survive. In the twentieth century its historic nature, different from other Lancashire towns, was a plus when it bid for one of the new universities in the 1960s. The University which was established here in 1963-4 immediately took an interest in its environs, leading to the creation of a Centre for North West Regional Studies, which in turn has fostered many studies of Lancaster and its region. The decay of traditional industry and of Morecambe’s status as a resort, has led to an increasing reliance upon tourism as a source of income. This in turn has bred a policy over the last fifteen years or so of promoting the ‘historic city’, as well as the beautiful countryside of North Lancashire, a policy which has been extremely effective and pursued by some very talented individuals.

It would have been difficult in 2002 to predict the changes which have impacted the city. Particularly we could not have foreseen the huge growth in overseas students at the University and the corresponding increase in accommodation for them in the city. Undoubtedly this helps the University financially, but a sudden shift in international tensions could change it all. In other guise the former Centre for North West Regional Studies has been reborne. The diminution in the role of local government, both city and county, has been reflected in the city’s public services and, in a degree, to its pride. Although availability of work has not notably increased, the attractions of the area have meant that there has been a huge increase in housing, especially in the urban area and immediate villages, such as Caton and Halton, while the growth southwards continues to form a ribbon along the A6.

It is difficult to predict the future of the city, but it is clear that many people find it a very attractive place to live and undoubtedly its rich history, its setting and its natural advantages will continue to be factors in its favour for many years to come.

One

Where do you come from?

There is a tendency among local historians to assume that until very recent times the population of most provincial towns and cities was homogenous and largely homegrown. This is manifestly untrue, as even a quick glance at our history will show. There seem to have been periods when local society was very varied in origin, and times when it was more uniform. In recent centuries prosperity has encouraged inward migration from less affluent parts of the countryside, from European persecution (Flemings, Huguenots and Jews) and latterly from countries of the former British Empire, while slump has led to emigration to other towns and cities, or to other countries where opportunity seemed to present itself, especially America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. In all this Lancaster is a microcosm of national behaviour, although it has experienced neither the range nor the quantity of inward and outward migration that some of its larger neighbours, such as Manchester and Liverpool or the cotton towns of East Lancashire, have experienced.

Many different peoples have lived on the banks of the river Lune, including those whose Neolithic pottery was found under a Roman building in Church Street. We have no evidence, direct or indirect, for their cultural affiliations or language until we meet the Celtic Iron-Age tribesmen of the Brigantes or, more probably, one of its more localised sub-tribes, who occupied the area on the eve of the Roman conquest. Whether they were native to the land or incomers we cannot tell. Celtic was not the first language in Britain, for traces of earlier language appear in place-names, perhaps even in the name ‘Lune’, but language and race are not synonymous. The Celtic language spread across Europe with an aristocratic warrior-culture and the use of iron, but the people who used it may not have been genetically uniform.

We know from Roman sources that the Brigantes were a very large and loosely organised tribe occupying most of northern England and southern Scotland. The Romans exploited their fatal weakness, disunity, to split them and ultimately to force them into direct conflict and inevitable defeat. The lower Lune valley may have been a distinct area known as ‘Contrebis’, if inscriptions at Burrow and at Folly Farm just north of Lancaster record an area name. North Lancashire may have been on the fringes of two tribes, but throughout the Roman occupation, from about AD 70 to AD c.450, and beyond, the majority of inhabitants of this region were Celtic-speakers.

From about AD 70 the dominant, as opposed to majority, language would have been Latin. The Roman invaders themselves, represented first by the army and administrators and then later by merchants and adventurers, were far from uniform. Some administrators and army officers may have been of Italian origin, but the ordinary soldiers were probably mainly Gaulish in origin, from modern France and Germany.

One of the most momentous discoveries of recent years has been that of the tombstone of a Roman cavalryman near the canal in Aldcliffe Road in 2005. This commemorates Insus, son of Vodullus, from Trier in Germany, a minor officer (curator) of the Ala Augusta, like Apollinaris. Mounted on a ridiculously small horse, Insus faces the viewer, holding in his right hand a short broad sword and the severed head of an enemy, over whose headless and kneeling body he rides. This is a characteristic pose for the depiction of cavalrymen on gravestones, although the beheading is not, and this type of monument is known as a ‘Reiter’, from the German for rider.

It was standard practice to raise auxiliary troops on the fringes of the empire, and the principal regiment in garrison at the fort was the Ala Sebosiana, raised in Gaul. Its soldiers were not even Roman citizens until they retired from the army, usually after 25 years’ service. Another soldier, whose tombstone was discovered in Cheapside in the eighteenth century, was Lucius Julius Apollinaris, a trooper of the Ala Augusta, who died aged 30 and whose place of birth was also Trier, now in Germany.

2 Roman altars from Burrow-in-Lonsdale and Folly Farm near Lancaster. Both of these record the name of ‘Contrebis’, which may be the epithet of a local god or even the name for the lower part of the Lune valley.

2a Tombstone of Insus, son of Vodullus, a native of Trier in Germany. A junior officer in the Ala Augusta (the Augustan Cavalry Wing) he formed part of the early garrison of Lancaster. The pose is characteristic of Roman cavalrymen, although the severed head of his enemy is a less common touch. Found in the southern cemetery, off Aldcliffe Lane, in 2005 and now in Lancaster City Museum.

While few military tombstones have been found here, depriving us of a useful source of knowledge for ethnic origin, we can make several assumptions based on more general evidence. All Roman forts had a hospital, and these were often staffed by Greeks. The island of Kos was particularly famous for supplying doctors. Greek doctors are recorded at Chester and elsewhere, while Burrow-in-Lonsdale has an inscription to the gods of healing in their Greek form, suggesting that Julius Saturninus, the dedicator, was a Greek. The only evidence of a hospital at Lancaster is a pair of bronze forceps from Vicarage Field, but it is a fair assumption that Greeks may have been here too. The merchants who thronged the streets and markets of the civil settlements outside the forts included many of more distant origin, including the eastern Mediterranean and north Africa. In fact Italian Romans would have been in a minority.

Many of these men, whatever their origin, will have arrived without dependents and a high proportion will have married local women. Within a few generations the racial mix is likely to have been complex, but all will have felt themselves in some way ‘Romans’. It was one of the secrets of Roman success that their culture, while apparently dominant, was also inclusive and allowed them to incorporate many other cultures into their own.

This area was settled late by Anglo-Saxon people. From the fourth century AD they had been colonising eastern England and gradually becoming the dominant culture, but their movement into the north-west via the Pennine passes was delayed by nearly two centuries. Lancaster must have been a mixture of resurgent Celtic and residual Roman influences at this time, lying at a crossroads between the vibrant Christian churches of Rome and of the Irish Celtic world, which were widely divergent in practice. The Celtic church brought missionaries and monks. The church of Rome maintained economic links with the Mediterranean world, and sites of this period in Wales and the south-west often have a distinctive archaeology, with imported Mediterranean pottery. Lancaster has not produced archaeological evidence for this period, but may yet do so.

The first Germanic Anglo-Saxon settlers started to arrive just before AD 600. This area of North Lancashire, perhaps a petty kingdom in its own right, was gradually absorbed into the great kingdoms of Northumbria and of Mercia. These two powers were mortal enemies in the seventh century, Northumbria having been converted to Christianity under King Edwin while Mercia under King Penda was pagan. What is now Lancashire was thinly populated and a border region of little importance, the prize of battles fought elsewhere. It is likely that the colonisation process here was slow, more one of intermarriage than of conquest and replacement. However, by degrees the dominant culture and language became Anglo-Saxon.

3 Drawing of the tombstone of Lucius Julius Apollinaris, a Roman soldier from Trier in Germany. Apollinaris died aged 30, presumably while on active service. The tombstone was found in Cheapside in 1772. From its position it may already have been moved from the Roman cemetery for re-use as a building stone. The only cemetery so far known was at the southern end of Penny Street and adjacent areas.

People with Anglo-Saxon names are recorded on the few inscriptions of the next three centuries or so. Stone memorial crosses found at Lancaster ask us in Latin to pray for the souls of Cynibad and Hardwine, while one in Anglian runes asks us to pray for Cynibald, son of Cuthberect. In this period many of our towns and villages were named. Unlike Celtic place-names, which tend to be purely descriptive, many of the Anglo-Saxon place-names incorporate personal names, presumably those of leaders and landowners. Names such as Melling, Gressingham, Heysham, Heaton or Caton are typical, the latter meaning the ‘tun’ (village) of a man called ‘Kati’. Some place-names, however, despite their modern form, are descriptive. Among these are Wray [‘village in the corner’] or Arkholme [‘at the shielings’, an Old English dative plural form].

4 Drawing of Roman bronze forceps. These forceps were found during excavations in the Vicarage Field in 1927 and indicate the presence of a hospital and doctor in the fort. Burrow-in-Lonsdale has produced an inscription (now in Tunstall church) to the gods of healing, Asclepius and Hygeia. Many Roman doctors were of Greek origin.

The Anglo-Saxons, a great deal naturalised after four hundred years of stability and intermarriage, were now to be the target for Viking raiders and settlers. The Vikings, of Danish origin, were genetically not unlike the Angles and Jutes, who came from the same area several centuries earlier. Some of these Danish-Vikings found their way across to the west coast. Place-names ending in ‘-by’, indicating ‘farm’, are their hall-mark, and the Lune valley has ‘Hornby’ right at its heart, perhaps indicating that the settlers’ route was via the river valleys. Most of the other Viking names are given by Norse settlers who came by way of Shetland, Orkney, the Isle of Man and Ireland. They arrived quite a long time later, in the tenth and eleventh centuries. Some of their place-names include Irish elements which they had picked up on the way. Among these are particles such as ‘argh’ or ‘ergh’, which form the endings of farm names and possibly indicate some form of transhumance, although this is still a matter of disagreement among place-name scholars. ‘Holme’, ‘Thwaite’ and ‘Dale’ for ‘meadow’, ‘clearing’ and ‘valley’ are typical, the latter giving rise to ‘Lunesdale’.

5 Anglo-Saxon Cross with a Latin inscription found in 1903 built into the medieval walls of the Priory church. This invites the onlooker to pray for the soul of Hardwine (‘Orate pro anima Hardwini’). It dates from the ninth century AD Another fragment found more recently names a man called Cynibad. Both are Old English names.

While Danish Vikings in eastern England seem to have renamed large tracts of countryside and the majority of village names, the Norse do not seem to have had such an easy task in the west. The landscape may have been more settled when they came, or they may have been content with what the natives regarded as more marginal land. At all events, they named the higher farms on the felledge, and those on the low clay islands in the coastal marshes such as Cockersand Moss, like Norbreck, Kendal Hill and Thursland Hill. Many villages with Anglo-Saxon names have fields with pure Norse names, so their impact may have been greater than we think. Fields are likely to have been named by their users, rather than their owners. Impact was greatest in the Lake District and across Morecambe Bay, in Furness, where the place-names of this period are dense and where Old Norse may have been spoken into the thirteenth century. Norse names can be found in a number of Lancaster’s fields, such as ‘Edenbreck’ or ‘Haverbreaks’, and even in the town centre, where ‘Calkeld’ Lane refers to the cold spring which until recently emerged in a cellar.

6 Anglo-Saxon Cross with an inscription in Anglian runes. The inscription reads ‘pray for the soul of Cynibald, son of Cuthberect’. It was found in the Priory churchyard in 1807 and is now in the British Museum.

Within a couple of centuries these settlers were overtaken by another group, the Normans, probably smaller in number but even more dominant in spite of this. Conquering the royal army and killing the king in 1066 had given them sway over the whole country, ironically because of the very centralised nature of the English administration. But they still had to earn their prize, and hold it. The Normans were another branch of the Viking raiders, who had settled in Normandy and absorbed some French culture, including the language. Their hold on English lands was fierce and based upon military might. Lords like Roger de Poitou, who took Lancaster as his portion some time before Domesday, probably felt little affinity with his new lands, preferring to give its ecclesiastical wealth to the abbey of his home-town, Seez. The Normans ultimately provided our legal system, part of our complex language, and many of our institutions, but in terms of influence on the landscape they had little effect. In the area around Lancaster only ‘Beaumont’, now part of Skerton, can be identified as a new place-name. Essentially, the small Norman ruling class left others to farm the land. On the other hand, their passion for order and information led to the first catalogue of land and its owners, Domesday Book, and hence the first record of our local place-names. By such means the names began to be fixed, coverage of large geographical areas leading to introductions such as ‘-le-’ to distinguish Bolton-le-Moors from Bolton-le-Sands, problems which had never troubled the essentially local Anglo-Saxon administration.

The Middle Ages are not a period in which we would expect many foreigners to make Lancaster their home. Most of the trade was focused on the south and east coasts, facing Europe. Nonetheless French pottery found its way to Lancaster, and was found in some quantity on the site of Mitchell’s Brewery in Church Street. Such pottery, from the Saintonge area, is thought to be a marker for the more-or-less invisible wine trade, so some French ships may have been involved and certainly the royal connections of the Castle would have meant access to a wider range of foreign goods and visitors than was the case with lower-status sites. The Priory, too, housed French monks between 1094 and 1414, drawn from the mother house of Seez. The names of some 21 priors are known, such as Emery de Argenteles (1337-42), John de Coudray (1344-5), John des Loges (d.1399) and Giles Louvel (1399-1414).

From the late seventeenth century at least, when Apprenticeship Rolls begin, Lancaster was drawing on areas such as Furness and the Fylde for its new blood. Young men who sought a good trade, or whose families sought one for them, came to Lancaster to be apprenticed. Sons of yeomen and rural labourers expected to give themselves an edge by gaining this experience, while Lancaster was also a closed shop, literally, due to its retention of Freeman status and the exclusive rights which went with this. Even into the nineteenth century the poorer rural areas, and those with fewer prospects, such as the Lake District, provided Lancaster with some of its most entrepreneurial spirits. Robert Gillow was the son of a poor widow from the Fylde, while the two manufacturing houses of Storeys and Williamsons were founded by incomers from Bardsea, in Furness, and Keswick respectively.

The movement was not all inwards. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Virginia called on many without prospects in this country, who set out to make their fortune in a new land. Among these were a few recorded in the Borough Records:

1682 Francis [sic] Robinson, of Gosforth, near Ravenglass, spinster, agrees with Robert Pearson of Lancaster, mariner, to serve four years in Virginia according to the custom of the country. (Pearson to pay her passage.)

6th Jan 1709 Mem. that John Fell and James Fell sons of James Fell sometime of Lancaster of free will and volition have consented before Mayor and Baylives of the said Corporation to goe to Virginia by the first opportunity and there to serve Mr Robert Carter of Lancaster and Mr Joshua Lawson of the same merchants and their or either of their orders for the Terme according to the Custom of the Country.

Many younger sons also set out for the West Indies as factors to merchant fathers, acting as local agents. Some made their fortunes and came back as nabobs. Many never returned, either through bankruptcy or early death.

Because of the slave trade the parish registers of Lancaster and several surrounding villages, such as Warton and Heysham, record the baptisms of black servants, presumably former slaves. What was probably the first black face ever seen in Lancaster belonged to ‘Richard Nigroe, son of Peter a Blacamore’, baptised at Lancaster in 1602. His arrival dates from long before the Lancaster slave trade had got under way. A more typical entry is that at Heysham in 1738:

Thomas A Negro Servant to Captain Peeter Woodhouse of Lancaster bapt. May the twenty first being upon Whitsunday.

Another entry in 1800, at Warton, records;

Edwin a Negro boy servant to Mr Law of the Island of Barbadoes baptised at Mr Bishop of Y[ealand] about 13 yrs old.

Black servants were very fashionable in high society in the early eighteenth century and were often given fancy names, but most of these servants must have returned with members of ships’ crews, whose family names they seem to have taken. Indeed, other than these particular church records, we could not distinguish by name alone most of the later black incomers from other individuals of local origin. We know in all of about seventy black men and women who appear in the Parish Registers because they were baptised or buried here. Baptism seems to have been taken at the time as an acknowledgment of freedom.

Two are better known than the rest. These are the man known only as ‘Sambo’, whose grave can be seen on the western shore at Sunderland Point, and John Dixon, a servant of the Lodge family at Bare Hall,‘a native Black, from the Island of Grenada’, whose tombstone of 1841 stands in Morecambe churchyard. Their lives were very different. The former, so legend tells, died of grief in the 1730s when he thought his master had abandoned him. Recently doubt has been cast on the actual existence of ‘Sambo’, suggesting that he was a figment of the imagination, or an embellished myth by a landlord at Sunderland Point wanting to increase tourism in the 1790s, when the story emerges. Personally I believe he did exist, and if he was not ‘Sambo’, then he was someone else of the same name. The latter died aged 79 following over 39 years in honoured domestic service and was commemorated by a tombstone at a time when many servants lay in unmarked graves. Frances Elisabeth Johnson, aged 27 in 1778, who worked for Mr Satterthwaite at 20 Castle Park, is one of only three black women to be recorded.

7 Grave of Sambo at Sunderland Point. ‘Sambo’ is reputed to have died in 1736. Sixty years later a brass plate with verses by Rev. James Watson, master of the Free School in Lancaster, was set on his grave.

8 Grave of John Dixon. Dixon, a ‘native Black from the Island of Grenada’, was a household servant for many years at Bare Hall and was buried in Morecambe churchyard in 1841.

From the Registers of the Priory Church, Lancaster:

Baptisms

Thomas John, a negroe, Jan. 3 1759

William York, a negroe, Jan. 27 1759

John Lancaster, a negroe, Feb. 2 1760

Henry Hind, an adult negroe, May 3 1761

John Thompson, an adult negroe, Aug. 23 1761

Richard Peters, an adult negroe, Nov. 10 1761

William London, an adult negroe, Jan. 20 1762

Rebecca Thorn, an adult negroe, Oct. 27 1763

George Stuart, an adult negroe, May 20, 1764

John White, an adult negroe, June 10 1764

William Trasier, an adult negro, Oct. 21 1764

Molly, an adult negroe, Nov. 6 1764 [burial recorded Dec. 1 in the same year]

William Leuthwaite, an adult negroe, Feb. 3 1768

Stephen Millers, an adult negroe, May 15 or after, 1768

Benjamin Johnson, an adult negroe, May 28 1769

Jeremiah Skerton, a black man, an adult, Nov. 17 1773

Benjamin Kenton, a black man, in the service of Capt. Copeland, Mar. 5 1774

John Chance, a black, aged 22 years & upwards in the service of Mr Lindow, Sept. 12 1777

[burial recorded on Oct. 8 1783]

Frances Elisabeth Johnson, a black woman servant to Mr John Satterthwaite, an adult aged 27 years, Apr. 2 1778

Thomas Burrow, a black, an adult, Feb. 15 1779

George John, a negro and adult, Jan. 22 1783

Isaac Rawlinson, a negro and adult, Feb. 3 1783

William Dilworth, an adult negro, Oct. 6 1783

Thomas Etherington, an adult negro, aged 22 years, Oct. 13 1785

There are also the following burials, for which less information is forthcoming:

A negroe, Nov. 14 1755

A negroe, Nov. 17 1755

John Bolton, a black, Nov. 20 1756

A Negroe Boy, Nov. 6 1762

Samuel Powers, a Negroe, Apr. 10 1765

Robert [ ], a black Man, Mar. 25 1778

9 Painting of a ship being built at Brockbanks yard. Attributed to John Emery (1772-1822), this shows Brockbank’s shipyard on the Green Ayre and St George’s Quay in the background in about 1806. On the right a ship’s hull is nearing completion – the date and the admiral figurehead make it almost certain that this is Trafalgar, a ship of 267 tons built for William & Samuel Hinde of Liverpool ‘for the Guinea Trade’, meaning ‘intended for the slave trade’. To the left is a pair of studded timber wheels, used for manoeuvring large baulks and tree trunks around the yard, while further left again a man is caulking a smaller vessel with hot pitch. In the background is the ruin of the old bridge with one arch missing (it was bought and demolished in 1802 by Brockbank to make it easier for his ships easier to get through) and the warehouses and shipping at St George’s Quay.

French prisoners-of-war were held in Lancaster Castle during the Napoleonic Wars. A Yorkshireman, Richard Holden, saw them here in 1808,‘… Many French prisoners in the body of the Castle now’.

German nationals of various description seem to have made up an important part of Lancaster’s nineteenth-century immigrants. Two, at least, were associated with the running of the sugar house in St Leonardgate, and perhaps another one in Cable Street. This business, set up by Robert Lawson in the early eighteenth century, was still running in the early nineteenth under George Crosfield & Co. It is clear that large numbers of Germans from the Hanover and Hamburg areas were involved in many of the British sugar refineries, and this possibly accounts for Heartwick Grippenhearl and Johann Hinrich Holthusen. The former became a Freeman of Lancaster in 1748-9, also listed in 1758 are Joseph Schrader and Jacob Gissing, although a directory of 1834 lists him at a second sugar house in Cable Street, as well as the one run by Crosfield in St Leonardgate.

We know of two or three other groups of nineteenth-century German immigrants. The 1881 census returns provide us with three interesting examples. At 103 Penny Street was the Kuhnle family, pork butchers on the New Market. George and Mary, both aged 29, are merely noted as ‘born Germany’, but their eldest three children were born in Sheffield, while the youngest two were born in Lancaster. It seems therefore that George and Mary had moved from Sheffield where perhaps they formed part of a German colony. Were they like the Yorkshire Schulz family described by Hartley & Ingilby, escapees from military service in an increasingly militaristic 1870s Germany? We may never know. With them lived John Speidal, aged 16, also born in Germany. At the same time a lodging-house at 11 China Lane offered overnight accommodation to nine members of a German band. No names or ages were recorded, although they had managed to indicate that they came from Bavaria; perhaps there was mutual incomprehension between the band and the owners of the lodging-house. German bands were very popular at this time. Wearing a rudimentary uniform they walked from town to town, playing wherever they could find an audience and collecting what money they could. Not all ‘German’ bands were German. The name covered a wide range of Czechs, Austrians and other nationalities. Finally, there was Laurenz Schmitz, born in the Rhineland and a teacher of music. The presence of a ‘Rheinheimer’ lodging-house on China Lane in around 1890 suggests other Germans may have been here. Germanic, Russian and Polish names may also disguise Jewish refugees from the many pogroms and other scares to which European Jews were subjected in the nineteenth century. There seems little earlier evidence for Jewish people in Lancaster, although a gradual return to England had been possible since the seventeenth century. However, the recent intriguing discovery in America of a ‘Book of Nikodemus’ published in Lancaster by Rabbi Jacob Bailen in 1784 must surely suggest the existence of a settled community.

10 Cartoon of German band from Punch magazine. So-called ‘German’ bands were very common on the roads of late nineteenth-century England as they walked from place to place, playing in towns and villages and just scraping a living. Many of them were actually from Austria or Czechoslovakia.

Signor Rodolphe Pandolfini was a rather mysterious character, born in Rome in 1832 and said to be both a Count and, at one time, influential in diplomatic circles. He had come to Lancaster in about 1874 on the invitation of Edmund Sharpe to help with some architectural work. He stayed on after Sharpe’s death, using his skills as a linguist to act as correspondent for Messrs Storey Bros and teach languages at the Storey Institute. He was also an artist and a photographer, and had he not died in his darkroom in 1897, thus precipitating an inquest, we might never have heard of him at all. The inquest showed that he died of natural causes.

From 1801 Ireland had been part of the United Kingdom and, as well as the huge outflow of Irish people following the disastrous Potato Famine of 1846-7, there was a regular flow of seasonal workers, usually men, to work the land and send most of the proceeds to families at home. Many of these labourers lodged in barns and outbuildings, happy to find cheap or free accommodation and make the most of their earnings. In arable areas much of the labour was only needed at harvest time, but there was a longer season in the potato-growing areas such as the Fylde and Pilling for both planting and lifting. Such was the Irish influence here that the local word for potatoes was ‘praties’.

There were also many Irish people living in Lancashire. It was close to the ferry ports and had a strong surviving Catholic element, which meant there was already a support system supplied with churches and priests. Many lodging-house keepers in Lancaster were Irish, and the building trade thrived upon the loose arrangements of casual Irish labour. A disproportionate number of Irish people were taken into custody, according to the Police Photograph Book of the 1890s, a sort of rough justice in which local drunkards were seen home while those without friends or relations spent the night in the cells.