11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

In the summer of 2008 Kimberley Motley quit her job as a public defender in Milwaukee to join a program that helped train lawyers in war-torn Afghanistan. She was thirty-two at the time, a mother of three who had never travelled outside the United States. What she brought to Afghanistan was a toughness and resilience which came from growing up in one of the most dangerous cities in the US, a fundamental belief in everyone's right to justice and an unconventional legal mind that has made her a legend in an archaic, misogynistic and deeply conservative environment. Through sheer force of personality, ingenuity and perseverance, Kimberley became the first foreign lawyer to practise in Afghanistan and her work swiftly morphed into a mission - to bring 'justness' to the defenceless and voiceless. She has established herself as an expert on its fledgling criminal justice system, able to pivot between the country's complex legislation and its religious laws in defence of her clients. Her radical approach has seen her successfully represent both Afghans and Westerners, overturning sentences for men and women who've been subject to often appalling miscarriages of justice. Inspiring and fascinating in equal measure, Lawless tells the story of a remarkable woman operating in one of the most dangerous countries in the world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Certain names and details have been changed to protect the innocent and guilty alike.

First published in the United Kingdom by Allen & Unwin in 2019

Copyright © Kimberley Motley 2019

The moral right of Kimberley Motley to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26-27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

United Kingdom

Phone:020 7269 1610

Email:[email protected]

Web:www.allenandunwin.com/uk

Hardback ISBN 978 1 76063 317 2

E-Book ISBN 978 1 76063 396 7

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

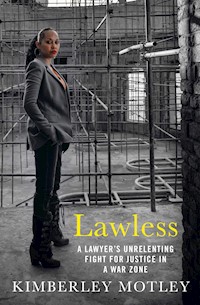

Cover photo: Kiana Hayeri (Kimberley Motley in Darul Aman Palace, Kabul)

For my beloved Deiva, Seoul, and Cherish.

I hope that one day you’ll understand.

Contents

Prologue

1 The playlist

2 The Manchurian Candidate

3 I’m not a terrorist, I’m a taxi driver

4 Please help us

5 My name is Irene

6 False pretences

7 Give me your watch

8 The minimum is not guilty

9 You need to sit down

10 I don’t have all day

11 Immoral crimes

12 Watch your back

13 Lock your doors and hide

14 Okay, baby. Breathe. Slow down.

15 Iron Doe

16 A man or a monster?

17 Wicked Ninja

18 Crocodile tears

19 Well, you must have done something

20 High fives

21 Article 71, I think

22 Oh … this is America

23 Motley’s law

Epilogue, The aftermath

Pic section

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

Prologue

Court is in session on the Spanish island of Mallorca. I’m sitting with my client, a young British man accused of selling drugs on the neighbouring island of Ibiza, when my phone vibrates in my pocket. I quietly slide it out and read the message sent by another client, Laila, who was recently kidnapped from Vienna to Afghanistan.

“I don’t know if they have guns,” the message says.

I scan the courtroom. It’s not good form for lawyers to send text messages while the court is in session, but Laila needs a quick reply. I begin to type, casually, trying not to draw any attention to myself.

“Are you wearing the black clothes?”

I hit send and get an instant response.

“Yes.”

“When you get in the car, we have a burqa for you. Put it on.”

“Okay.”

I think back to the first time I saw a burqa in 2008 when I arrived in Afghanistan. I had found the ghoulish blue head-to-toe coverings both terrifying and maddening; a visible sign of the oppressive culture of misogyny that was rife in the country. Ironic, then, that I’m now using the burqa to try to free Laila.

I listen as our witness is being questioned by the prosecutor. If found guilty, my client is facing nine years in a Spanish jail and a lifetime stain on his record as a convicted drug dealer. I turn to him and offer a reassuring smile. He listens nervously as the prosecution continues their cross-examination.

“Relax,” I whisper.

I watch the prosecutor as he works our witness. Our witness is consistent, assured, confident. Good man, I think to myself. He’s answering all the aggressive questions perfectly. Just as I would answer if I were in his position. I try to concentrate, but my mind keeps darting back to Laila. What is she doing? I wonder.

Keeping my phone out of the sight of the judges, I check it again. Nothing at first, but then it vibrates in my hand, almost making me jump. I open the text. It’s from one of my guys; they’re outside the house in Afghanistan where Laila has been imprisoned for months. The coast was as clear as it was going to get.

I text Laila again.

“The gate is unlocked. The car is outside. Get in it.”

I send the message. I can feel my heart rate rising. Another text.

“I’m scared.”

“I know. Get in the car Laila.”

One of the judges from the three-judge tribunal eyes me disapprovingly from the bench. I smile back and return my focus to the witness. My phone buzzes again.

“I can’t,” texts Laila.

Fuck.

Like many trafficked victims whom I’ve rescued over the years, Laila is showing signs of psychological confinement. She has a small opportunity to escape, but fear has taken over. Frozen in Afghanistan, she was terrified to make a move. I have an idea.

“Do you have the headphones with you?”

“Yes.”

“In two minutes go to the bathroom. Put the headphones on. I’ll send you a voice note.”

I had had a sleepless week, what with locating Laila, setting up her rescue and preparing for the trial in Mallorca. And now, for the first time in six days, when we only have a few precious minutes to rescue this young woman, she’s lost her nerve. If we don’t act now, she’ll disappear to Pakistan and we may not find her again. It’s now or never.

Back in the courtroom the prosecutor droned on with her cross-examination. I start coughing. I cough as hard as I can until the whole court has stopped what it’s doing and everyone is looking at me. I hold up my hand as I cough harder. A little concerned, the judge who stared at me earlier raises an eyebrow as if to say, “Are you okay?”

“We are going to take a quick break,” she says, eyeing me suspiciously, but also probably hoping I’m not going to cough up a lung.

I nod to her, wait for the judges to leave the court, then run out of the courtroom to the bathroom, locking the door behind me.

“Laila,” I say, into the phone, “listen to me very carefully. You have five minutes to get in the fucking car. If you don’t, we will be gone forever. I will not look for you in Pakistan. I will not help you anymore. I will never answer your calls. Five. Minutes.”

In the ten years I’ve been based in Afghanistan, I’ve represented multiple clients from different countries with vastly different backgrounds, who have had challenging legal issues, many in intensely dangerous situations. I know this territory now like the back of my hand, and although for me it has become just another day’s work, I know that for Laila every second could be the difference between life and death.

My phone vibrates.

“Ms Motley, please don’t leave.” Laila texts.

I text back.

“Four minutes.”

1

The playlist

In 2007 I was living and working in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Milwaukee is where I grew up. It’s where I went to school. It’s where I started my life with my husband, Claude, and it’s where we had our three kids, Deiva, Seoul and Cherish. I know Milwaukee better than I know myself. Although that doesn’t mean I have to like it.

Ever since I was a kid, Milwaukee has been the most segregated city in the United States.1 It’s a place that incarcerates more black men than any other city in the US so that now more than 50 per cent of black men in their thirties and early forties have been incarcerated in some type of state prison.2 In 2018, Milwaukee was deemed the worst place in America to raise a black child.3

These may seem like just another set of grim urban statistics to you, but they are more than just numbers to me. They represent the experiences I’ve had my whole life.

I grew up in the projects. When I was seven, my best friend was a girl named Janine. I would go to her house every day to play, and I can still remember her mother, a beautiful woman who was always kind to me. I remember how sometimes she would bake us cookies. One night I was lying in bed when suddenly the street was lit up by the lights of ambulances and police cars. The sirens rang out and I could hear voices shouting outside my window.

The next day I found out that Janine’s mother had been murdered by her father. She had tried to get away, banging on people’s doors, crying for help, but no one opened up their door for her. Her husband beat and stabbed her to death in the street and threw her body in the green dumpster that I passed when I walked to school every day.

When I was nine, my two brothers and I were playing baseball in the neighbourhood playground and an older teenager came over to borrow our bat. He took the bat from us and beat the shit out of another kid in the middle of the street right there in front of us.

That is Milwaukee. It’s the city where I was born and raised. It’s a city that I love and hate. It’s the city that made me who I am and prepared me for whatever the world could throw at me.

Despite growing up in the projects, not going to college was never an option. Not with my Korean mother and African-American military father. Even though I had my heart set on other things, they expected me to go to college to get a degree. Still, it wasn’t until I was twenty years old and pregnant with Deiva that I decided to focus on getting a paralegal degree so I could find a job that earned enough to provide for her.

I have always had an interest in the law. When I was two, my father was nearly killed in a car accident while he was working, but not only did his then employer, General Electric (GE), refuse to pay compensation for the disabilities he suffered as a result of the accident, they actually fired him. He was forced to sue. The case rumbled on for years and at times was the main focus of life in our house. Eventually it went to court and he lost. That transformed life for us because, while we weren’t rich before the accident, we were definitely poor after it. We even had to give away our dog.

After earning my paralegal degree, I finished my Bachelor’s degree in criminal justice and then went to graduate school and law school at two different universities simultaneously, graduating in May 2003. I wasn’t yet sure in what area of law I wanted to practise, but I’d tell people “anything but criminal law” because I had grown up in that world and seen enough of it to last a lifetime. But when the Milwaukee Public Defender’s Office visited our campus and I started talking to one of their recruiters, she convinced me that I was well suited for the work and offered me a job. Already pregnant with my second child, Seoul, it seemed easy to say yes.

Becoming a public defender is for a lot of people the first time they’re introduced to poverty. It can be quite a culture shock. In order to be a lawyer worth your salt, you have to know the law but also how to deal with people who might be very different from anyone you’ve ever met. So as soon as I started working at the Milwaukee Public Defender’s Office I could tell I was unusual. While for most of my peers, this was the first time that they’d seen criminal activity up close, I’d been conditioned to it since I was a little kid.

It takes a special person to be a really good public defender, to be that kind of advocate, because it’s more than a job, it’s a lifestyle. Unfortunately, it didn’t take long before I began to feel that that lifestyle wasn’t what I wanted. I felt increasingly like I had to choose between being a good lawyer and having a good life. I’m not saying that I had to be super-wealthy, but it frustrated me that I couldn’t do my job well and also live a full life outside of it. Our system in the US just doesn’t allow for people to do that work, represent poor people and have enough time or money to support a family.

Like most public defenders, I was overwhelmed with cases. I was required to represent somewhere between 200 and 250 people per year, which meant there was little time to go to the office or have meetings or to do any of those other things you might think a lawyer does with her day. My days began with dropping off my eldest daughter and son, Deiva and Seoul, at school and my youngest daughter, Cherish, at child care. I then spent the rest of my time running between the court and the jail.

The day I met David was a pretty typical day.

I had dropped off the kids that morning and had been bouncing from court to court. Or, as in David’s case, fronting up to argue bail.

The way our Public Defender’s Office worked was that we took bail hearings on a rotating basis, so when you’re on you argue bail for everyone arrested that week. Whoever they might be, whatever they’ve done, you try to make some kind of reasonable argument no matter how hopeless. I’ve literally stood up in a bail hearing and argued that the fact my client has actually showed up, albeit in handcuffs, is sitting in court politely and promises that he won’t run (this time) are positive factors that the judge should consider when setting bail. You do what you can.

So the day I met David I’d arrived at court and knew I had around ten minutes to see what we might use to convince the court not to incarcerate him. To be honest, I was on autopilot because I’d seen ten Davids already that day. Or so I thought.

Something about David’s file was unusual. He was still in high school; I could use that and argue that he was less of a flight risk. He had no prior record, which definitely helped, and he also had a part-time stable job—another bonus. Before I’d even considered the details of his case I had figured this kid had a good shot at being released on bail.

David was a seventeen-year-old black kid who was preparing for his prom. To get himself looking his best, David went to get a haircut at the local barber shop. He sat down in the barber’s chair, and while the guy was cutting his hair the other guys were shooting the breeze like guys in barber shops do. Then one of the guys pulled out a gun that he’d just bought from some guy on the street.

Everyone was excited at the sight of the gun. They started laughing and joking about it as the barber removed the clip and passed it around. Everyone in there took turns holding the gun, admiring the gun, talking about the gun, goofing off a bit. Eventually the gun landed in David’s hands.

Now, let’s remember the gun had no clip. David held up the gun, examined it, and pulled the trigger.

The bullet fired across the room and struck another seventeen-year-old kid sitting in the chair opposite David. Just like David, Mike was there that day getting his hair cut for his prom. The bullet struck Mike in the head and killed him instantly.

David dropped the gun and yelled, “You didn’t tell me there was one in the chamber!”

He panicked and tried to help the kid bleeding on the floor. David screamed for help even though it was clear there was nothing that could be done.

The other guys in the shop must have panicked too because they started getting aggressive with David, telling him he needed to get the hell out of there. They forced him out of the door and David ran home. He told his older sister what had happened. She packed him a bag and told him to get the hell out of town. His sister instructed him to head to Chicago and lie low.

Somewhere between his sister’s house and Chicago, David’s conscience and good sense must have kicked in because instead he walked to the nearest police station. He told the police what he’d done, and like any officer would in that situation they sat him down and asked him to write down a full confession.

But then David did something very interesting.

Instead of writing a confession, he wrote a letter. The letter was addressed to the mother of the boy who he had just shot hours before. It was contrite, full of remorse and sorrow for what had happened. In it, he explained that it had been a terrible accident and that he was sorry for the pain that he had caused.

The police officers promised to share David’s letter with the victim’s family (which they never did). Ultimately, he was charged for murdering Mike.

A couple of days after he’d been released on bail, David came to my office. He walked in wearing his high school letterman jacket, eyes scanning nervously around the room. It was obvious that this was the first time he’d been in any kind of trouble. Just as he’d been at the hearing, he was polite and humble, but his fear was palpable. Being a public defender, you get used to seeing a lot of people who commit crimes and you get used to their swagger, the way they conduct themselves, the way they look at you, talk to you. But right away, as I measured up this teenage boy standing in front of me, I thought, “You ain’t supposed to be here.”

I felt strongly that we had a case to bring to trial. Though what David had done was ill-advised, there was no intent; it had been an accident and so there was a chance to win if we went in front of a jury. But David was firm. He felt so bad about what he’d done that he simply wanted to plead guilty and take his punishment.

“I deserve to go to prison for the rest of my life,” he kept saying over and over.

He seemed genuinely remorseful, like all he wanted was for everything to stop and for the pain and guilt to go away. I wasn’t sure volunteering for prison was the best way to achieve that. I tried to talk him through his options, but his mind was set. He wasn’t listening. All he said was, “I should never have picked up that gun.”

So David began to go through the exact details of what had happened that day. I was surprised when he told me that he had confessed at the police station. I was particularly interested in how the police had extracted that confession from him. I wondered if they coerced him or put words in his mouth. That’s when he told me about the letter he’d written to the kid’s mother.

“Didn’t she get it?” he asked me. I doubted it, but I decided I’d ask for a copy.

Two weeks later, David and I met again. This time back in the courtroom. David pleaded guilty and a court date was set for his sentencing.

In court, the prosecution agreed with David: that he should never have touched the gun. They called the victim’s parents up to the stand and they impressed upon everyone what a good person Mike had been. I couldn’t argue with any of this. When it came my time to present David’s case, I was determined to show what a good kid he was, too.

But when I stood up I froze.

I had spent the last month working hard to put together strong arguments to justify a light sentence for David. By pleading guilty, we already knew that he was going to prison, so all I could do was try to get his sentence reduced as much as possible. I had compiled character references from the school, his boss, people who’d known him his whole life. They all stood by him. He was a good kid. This wasn’t some gang-related assassination but a terrible accident that had robbed two promising young black men of their lives because we live in a country where guns get passed around at the barber shop. After countless hours discussing the case with David, I could only admire his maturity and willingness to accept responsibility. I speak from experience when I say how rare that is.

But in that moment, as I stood in front of the court, I changed my mind about how to present my arguments. I’d given sentencing arguments and presented character references a hundred times before; the court had heard millions of them. And I’d defended gang members and murderers; the results were nearly always the same. I knew I had to do something different for David.

David’s family sat on one side, while Mike’s family were seated on the other. I stood up and glanced at the boy sitting next to me, swimming in the oversized suit his father had lent him, head down, crying. I looked at the notes that I had spent hours writing with all the positive letters in support of David.

Judge Donald urged, “Ms Motley, please proceed.”

Putting aside my notes, I looked again at my client and decided to shuffle my playlist. I reached for another document at the back of David’s file—the letter he had written to Mike’s mother hours after the shooting.

“Ms Motley …” Judge Donald repeated impatiently.

“Dear Ma’am.” I began, clearing my throat. “I’m sorry. I am so sorry for what I have done …”

I have always believed that the law needs to be practised with humanity. A lot of my colleagues disagree and prefer to rely on the rules to guide their every step through the legal process. We’re trained to learn the book so that we can follow it, but I think sometimes you have to throw the book away and do what feels right. As I read through David’s letter, I knew it said more than any character reference ever could.

“I think about all of the times I’ve seen your son at this barber shop before,” he’d written. “I’ve never spoken to him, but he seemed like a very nice person. My father always taught me not to touch guns, that guns are not toys, and I should have known better. I’m so sorry that I killed him and I wish I was dead instead.”

I’ve always wondered how David must have felt walking to the police station, the thoughts going through his mind, the weight on his young shoulders. How he must have felt as a seventeen-year-old kid who had just killed somebody after he’d been told to run away, to hide, to avoid recrimination. What strength David showed to instead make the decision to say, “No, I’m going to handle this.” What did that take? I can’t imagine what that walk felt like on his young legs.

Reading David’s letter was so emotional and raw that it was difficult for me to even get through it. When I’d finished, I sat down and the court was silent. The judge took a minute before he addressed us.

“This is one of the most difficult sentencings I’ve ever had to make as a judge,” he said. “I recognise that you’re a good kid. Mike was also a good kid, too. But still there was a life that was taken …”

Then he sentenced David to three years in prison.

It was the best result that we could have hoped for. I hugged David before they took him down. Then I experienced the most powerful thing as I left the courtroom and walked down the hall. I saw the two mothers, David’s and Mike’s, talking to each other in the corridor. Two women whose lives had been destroyed, consoling each other for their loss.

There were no winners in the courtroom that day. I used David’s own words to defend him, to protect him. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was exploring something new, something outside of what I’d been taught in law school. I didn’t realise it then, but it would become a cornerstone of a legal style that would come to define my career.

In the meantime, I saw that this was another example of the reality of Milwaukee. It’s a town where even good kids get shot dead and other good kids end up in prison. Watching the two mothers mourning their sons must have flicked a switch somewhere inside of me because suddenly I felt a profound sense of sadness as well as urgency. I knew I needed to get away from that place. I needed my children to grow up somewhere else because otherwise, one day, I might end up like one of those women.

2

The Manchurian Candidate

Shortly after representing David, I began to send out my résumé and started hitting up friends for leads on other job opportunities. Friends like Megan.

Megan was a colleague and every couple of months we’d have lunch and catch up. She wasn’t surprised to hear me admit that I thought the time had come to leave the Public Defender’s Office.

“Well … I’ve got this friend who is doing some cool work,” she said.

“Really?” I replied. “I’m keeping an open mind right now. Just as long as it’s not in Milwaukee.”

“It’s certainly not in Milwaukee,” she laughed. “He’s working in Afghanistan training and mentoring Afghan lawyers.”

I still remember my reply: “That sounds cool. Can you connect us?”

At that point I had never left the United States. I was as green as apples. If you’d shown me a world map, I’d have struggled to find Afghanistan on it, let alone tell you anything about the place. All I knew was I needed to get my family out of Milwaukee and to do that I needed another job. So I sent an email.

“Hi. I just had lunch with our mutual friend Megan, who told me about what you do. It sounds really cool and just in case you ever need somebody, attached is my CV.”

I didn’t think about it again. I’d sent out so many résumés that week that this was just another on a long list. But it turned out to be the email that changed my life.

It was the end of a long day and I’d only gone to the office to collect files for the following morning. My desk is usually a sea of chaos, which means I’m usually stressed that I can’t find what I need. Added to that, after a full day in court my sense of humour has usually knocked off long before I have.

I’d finally found everything I needed, packed it all away in my backpack and was heading out of the door when my phone rang. I had one of those “Do I really have time for this?” moments before I finally picked it up.

“Hello. Is that Kimberley Motley?” The voice on the other end sounded like it was on speaker phone. The line was so terrible I could hardly make out what he was saying.

“Who is this?” I really needed to pick up the kids.

“I’m Tim and this is George,” said the voice. “I’m calling from JSSP in Afghanistan. Do you have a couple of minutes?”

The JSSP or Justice Sector Support Program is what Megan had been telling me about over lunch. George was the country director of JSSP and he began to fill me in on their background. JSSP was set up in 2005 and, according to the US Department of State, was the largest rule-of-law program of its kind anywhere in the world. It was set up to support the Afghan government in the development of a justice sector capable of managing, equipping, enabling and sustaining its own criminal justice system.1 In other words, it was part of the US “Nation Building” strategy. Due to Afghanistan’s embryonic legal system, Team America had been tasked to help them build a better one.

I hadn’t even looked up the job. I didn’t know what a JSSP was or what the job involved. I’d simply sent a speculative email and not thought about it again. Now it seemed like I was in the middle of some kind of impromptu interview with two guys on the other side of the world.

The whole time I was thinking, “Who just calls you out of the blue for a job in Afghanistan?” It didn’t seem real.

After about half an hour, George and his sidekick explained that they wanted to move me forward to the next stage, which meant I would be invited to a ten-day training course in Virginia. At that point, I had to say, “Whoa!” Ten days? I didn’t just have ten days to take off to go to Virginia.

“You’ll be paid $10,000 for your time,” George said.

Okay, ten days. I could make that work.

Money was tight. Money’s still tight. I guess everyone always says that, but back then, believe me, it was really tight. On top of our college loans, Claude and I had three kids (my youngest, Cherish, had come along after three years of my working in the Public Defender’s Office, in 2006), a mortgage, unpaid bills and all the usual headaches a young family has. Three nights a week, after I left the Public Defender’s Office, I would cross town to work my second job lecturing at the local community college. Ten grand was pretty much what five months of Cherish’s child care bill came to, so there was no way we were going to miss out on that kind of money.

A month later, I boarded a plane to Arlington, Virginia.

I was picked up at the airport by bus and driven to a hotel on the edge of town with around twenty other people, mostly lawyers, almost all men. I was one of three women. Since the small talk revolved around what everyone’s experiences had been working internationally I kept pretty quiet, listening and taking everything in.

The trainers running the course came to meet us off the bus, four guys in khaki pants, Oxford shirts, military boots and Oakley sunglasses. I’d never seen people dressed like that before. I felt like I’d stepped into a quasi-military exercise.

You’ve probably seen the movie Private Benjamin, and though I’m not saying we were scrambling under camouflage nets or anything like that, it’s still a useful frame of reference for how ridiculous those next ten days of my life were to become.

The focus seemed to be to make us as terrified of Afghanistan as possible. We were billeted in a pseudo-military base and treated like new recruits. Like Manchurian candidates, three days in we spent a whole morning watching nothing but videos of things and people who had presumably been blown up in Afghanistan. We spent a day doing covert convoy driver training where we learned how to avoid kidnap and capture. Then one afternoon they drove us into the woods and taught us how to shoot. It was the first time I had ever held a gun.

They were trying to toughen up the soft lawyers. It seemed like they wanted us to believe that when we walked off the plane in Afghanistan suicide bombers would come running up to give us a hug.

This was clearly not my world. There’d been some kind of mistake. I decided early on that I would just keep my head down, collect my ten grand, get back to Milwaukee and find a real job.

Meanwhile, the white male American contractors in their Oakley sunglasses tried to teach us about cultural sensitivity. Mostly that involved encouraging the women to be submissive; don’t look a man in the eye, never ever shake hands with a man, always wear a headscarf. A lot of it was just a bunch of bullshit about what they thought Afghans wanted. And you know there wasn’t a single Afghan in that training. Not one.

But they did get my interest when they told us what the salary would be. Now, bear in mind that at that time I was making $51,000 a year at the Public Defender’s Office, plus another $5,000 from my teaching job. The JSSP job in Afghanistan would more than triple that. Suddenly, I really wanted that job.

I got home from Virginia tired and a little deflated. Even if I didn’t want it to work, I now desperately wanted a job that paid that well and could catapult us out of Milwaukee.

Before I could even offload to Claude, he told me his good news: he’d been accepted into law school in North Carolina. I was so pleased and proud of him, but I was also thinking, “How much is that going to cost?”

Claude’s news meant I needed the Afghanistan job even more. Moving to North Carolina made sense. It was exactly the kind of place we’d been looking to escape to. It was safe, clean and there’s no snow. Plus, there are really good Big Ten colleges in North Carolina: Duke, UNC and Chapel Hill are all nearby. Suddenly, I was thinking about a long-term future out of Milwaukee. All we needed was the means to make it happen.

Shortly thereafter, I received my formal offer to join the JSSP. I was excited about the opportunity but sad that I would have to leave my family to pursue it. I would leave for Afghanistan in September 2008 on a twelve-month contract.

Claude accepted his place at law school and we moved the family across the country to a new house and a new life in August 2008. I immediately felt the pressures of Milwaukee and the safety of my family had been lifted off my shoulders—only to be replaced with the new pressure of navigating uncharted territory. The better this new life felt, the more I was terrified it wouldn’t work out.

I was also concerned with how my kids were going to get on in a new place without me. They were all starting new schools. Cherish, now two years old, would be starting at a new child care centre; Seoul was going into the second grade and Deiva into the sixth grade. We wouldn’t have the extended family support we had relied on in Milwaukee and Claude would also be a full-time student in law school. He’s a great dad, but he had never really been left on his own with the kids for any length of time before.

The challenge of a new job was also playing on my mind. I was fixated with the others I’d met in Arlington. They’d all worked overseas before so I feared they would know exactly what they were doing while I wouldn’t know anything. I was scared I’d look stupid in front of them.

The night before I left, I stayed awake thinking, “What if something happens to me? How are they going to cope?”

I knew I’d be back in two months for my first leave. Until then, I had to say goodbye and get on with it. The sound of Seoul crying when I left for the airport will always stick with me. At least Cherish and Deiva were sleeping when I kissed them goodbye. I hoped that one day they’d be able to understand that this was not the number-one choice for me or Claude.

Two days later, after a short stopover in Dubai, I was stepping off the plane, brand-new passport in hand, on to Afghan soil for the first time. This wasn’t like going to the Bahamas. I was acutely aware of all that I’d heard and read during my training, and as I blinked in the bright sunlight to focus on the huge mountain peaks in the distance, I realised I was terrified.

What the hell have I gotten myself into? I wondered.

I was clutching a red headscarf; I had decided not to wear it in order to have an unobstructed view of this new place. I stared out across the tarmac into the desert, stunned by the natural beauty of the desolate landscape and the mountains in the distance. A bus arrived with bullet-sized holes in the window, and as it ferried us across the runway towards the terminal I became aware that my two new American male colleagues were eyeing me nervously. I was still clutching the red scarf. I glanced across the bus to another woman on board who had already covered her head. We exchanged smiles, a non-verbal understanding that we were both entering a world where we were about to unwillingly become second-class citizens.

The two male colleagues were still eyeing me nervously as I stepped off the bus. I tried to remember some of the things we were told by the American men who trained us in Virginia about how a woman “should” conduct herself in Afghanistan. Don’t initiate a conversation with a man, he is to speak to you first; wear your headscarf (Golden Rule number one already broken); don’t ever touch a man; no public dancing; and, last but not least, keep your head on a swivel.

Inside the airport we were swarmed by men looking to help with our luggage. The noise, the new smells, the signs in what looked like Arabic script—it was all overwhelming. I avoided engaging with anyone, instead looking around, clocking the armed men patrolling the baggage area. Eventually my bag arrived on the carousel and I gave in and let one of the baggage guys take it. I followed behind him as our group made its way outside into the hot, dusty streets of Kabul.

Our local contacts were waiting for us at an armoured SUV in the car park. Before we got in, we were each handed a bullet-proof vest and hard hat. I had to slide an AK-47 along the back seat to sit myself down. The car sped along the bleached, dirty streets while I struggled to take it all in. The horns of the oncoming traffic screamed as vehicles whizzed past us on both sides, we braked for a man leading a small flock of goats across the road, boys played with kites up on the roofs, while down below the sidewalks were packed with women in cornflower-blue burqas, men in shalwar kameez, amputees begging, people selling fruit and vegetables. There were people everywhere. It was like nothing I had ever seen or imagined. Still so true.

We drove to what would become our new home: a type of makeshift office compound in the centre of Kabul. Our four-car armoured convoy stopped and the drivers signalled to the gatekeepers to open the huge metal gates. We drove inside a compound that housed three huge buildings surrounded by high, concrete reinforced walls topped with razor wire.

I was acutely aware for the first time that I was in a war zone. Far, far away from my comfort zone.

That night, my first night in Kabul, I couldn’t sleep. I was filled with anticipation, fear, sadness, loneliness and frustration. As the sound of helicopters overhead came rumbling through the walls, I ran over and over in my mind what the kids and Claude might be doing.

I got out of bed and locked my door. Somehow that made me feel better.

3

I’m not a terrorist, I’m a taxi driver

After the initial shock of finding myself living in a war zone, I started to enjoy my new work at JSSP. I was full of optimism about how we could make a difference in a place that clearly needed help establishing rule of law.

I came to Kabul to work, but right away I could see how green I was compared to the other new JSSP recruits. It seemed like everyone else was well travelled, had worked on other international programs and had a wealth of experiences that I’d never had. So my motivation from day one was to make up that ground.

I was assigned to work on establishing training programs for defence lawyers. The aim was to enhance the skills of the Afghan lawyers by showing them the American way of doing things, which seemed logical as that was the legal system we were used to. At first, I fell into the trap of believing things would be that simple.

One of the key points for me when practising law is understanding the environment. It’s something that I constantly consider when I’m in a courtroom. I need to think about which court I’m in, which judge I’m facing, what the mood in the room is. There’s no such thing as a solution that works everywhere for everyone. One of the biggest mistakes that America made when we came to Afghanistan was to employ a “this is the right way” mindset that everyone was expected to blindly follow.

A good example of how we got things wrong was when the US sent American police officers to train and mentor Afghan police. The Americans began by equipping the Afghans with their “kit”, which consisted of the kind of uniforms a US police officer would wear. Of course a uniform is important for the police because having the same clothes makes everyone feel like they’re part of the same team. Sounds good in theory, but the police trainers failed to factor in something crucial about the environment they were working in.

Before they could even get into the substantive part of the training concerning how to conduct arrests, interrogate, take statements and all the important stuff, they discovered something else important: most Afghan men wear sandals. The wiping of the feet is part of the ritual of purification in Islamic faith. So when the Afghans received their US standard-issue boots, they didn’t know how to tie them.

The first days of the course were spent training the new recruits how to tie their shoelaces. Like Charlie Brown expecting the football to be there when it wasn’t, it was a miscalculation that I saw repeated by the Americans time and again. It was the same at JSSP and indeed everywhere else in Afghanistan. Too often it was “our way or the highway” and it didn’t make sense.

After a couple of months at JSSP, I began to question why there weren’t any Afghans involved in the development of the training materials. Our “capacity-building” mission was led almost exclusively by Americans, and for the most part we only used the Afghan lawyers on staff as translators rather than as subject matter experts. The Afghans we worked with at JSSP had virtually no voice in how we trained them in the legal structure we were ostensibly building for their country.

Even though the mission was funded with American dollars, it didn’t explain why everything had to be completely monopolised by us. For example, training on anything that had to do with Islamic law was forbidden. I’m not saying it was our place to teach the Holy Quran, but it was the sort of thing that we should have included in the training. Legally speaking, in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan there is no separation of church and state.1, 2

Instead the Afghans were kept at arm’s length. No matter how hard our local counterparts tried to help, they were always met with a superior, dismissive attitude from the senior management at JSSP. This attitude extended to all aspects of our relationship with the Afghans. They weren’t allowed into certain meetings. They worked in the basement while the Americans worked on the main floor. There were two separate kitchens, one for Afghans and one for us. Meal times were completely segregated, the Afghans dined in another room to that of the Americans. It was like we were there working near the Afghans, but we weren’t working with them.

One afternoon, I decided to ask some of the Afghans in my team if I could join them for lunch. They didn’t hesitate. Of course they said yes and made a space for me. I didn’t know until later, but it was the first time any American had ever asked.

I learned a lot at that lunch. I sat with Mustafa, Angela and Idress. Mustafa told me about how the Taliban would snatch women off the streets, beat them and sometimes even kill them. He told me about how the once-popular swimming pool was drained only to be used as a place where people were hanged from the diving board. He told me how the Taliban had destroyed some of Afghanistan’s oldest and most sacred religious landmarks, like the Bamiyan Buddhas, because they represented religions other than Islam.

I learned, too, that every day many of the Afghans at JSSP either shared their food or did not eat at all so that they could take the leftovers home to their families.

After that meal, I thought it would be a great idea for everyone to have lunch together. I asked the American lawyers why they thought the Afghans didn’t eat with us. My colleagues shrugged and John, my boss, told me it was because they didn’t want to.

“But there’s a lot we could learn from them,” I said.

“They’ve all passed security checks,” someone chimed in as though that was the issue.

“Good to know,” I replied, winking and swallowing my sarcasm. “Do you think maybe it might be worthwhile then—for security reasons and all—if we could get to know them a bit better?”

“What do you propose?” John asked.

“What if we just invited everyone to lunch,” I replied. “Maybe the Rose Garden would be nice.”

Somewhat reluctantly, John agreed, and a few days later in the beautiful flowered garden East met West for lunch.