Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

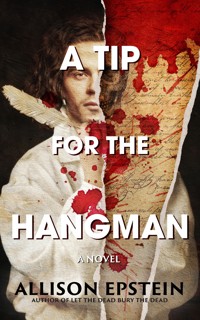

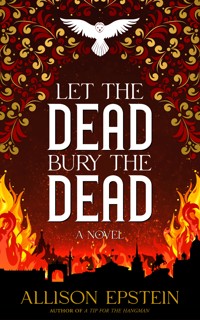

"Epstein imbues this alternate history with elements of fantasy and folklore to create a heady, transportive read."—Shelf Awareness A spoiled prince who might become a hero. A tired soldier, in love with his country and the man he serves. A revolutionary, risking her life for justice. And a woman who commands the wind and snow, and whose owl-amber eyes promise everything you've dreamed of… Allison Epstein's Let the Dead Bury The Dead unfolds an alternate history of nineteenth-century Imperial Russia, where politics, idealism, intrigue, and desire weave plots that reach from the meanest back alley to the grand Winter Palace… Fifteen miles from St. Petersburg, the tsar's younger son, Felix, chases pleasure in social exile. When Sasha, his beloved personal guard, arrives home from war, both men expect a peace of their own at last. But Sasha returns carrying a strange woman he rescued from freezing in the tsar's wood. Sofia Azarova soon captivates Felix with tales of suffering in Petersburg and insinuates that the prince can save his people. She teases Sasha about his conviction that she is no mortal, but a vila, a folktale come to life. And in a cramped Petersburg apartment, Sofia urges on Marya, right-hand woman of a rebel group torn between idealism and bloodshed. None of them understand Sofia's full intent. But as she guides them together, their lives will change forever… Praise for Let the Dead Bury The Dead "Epstein weaves a sweeping love story set against the backdrop of a cleverly reimagined Imperial Russia, glittering, gritty, and pushed to the very edge of rebellion by a dark creature of legend, a delightfully powerful femme fatale that will seduce anyone who meets her—or destroy them."—Olesya Salnikova Gilmore, author of The Witch and the Tsar "Epstein's unique retelling is richly enhanced by Slavic folklore, and the confusion between duty to family or country is expertly portrayed. Historical fiction fans will be spellbound."—Publisher's Weekly "A vividly imagined tapestry of turbulent times."—Kirkus

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 552

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Let the Dead Bury the Dead

Copyright © 2023 by Allison EpsteinAll rights reserved.

Published as an ebook in 2024 by JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.Originally published by Doubleday in 2023.

Cover design by Tara O’Shea

ISBN 978-1-625677-44-0 (ebook)

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

49 W. 45th Street, Suite #5N

New York, NY 10036

http://awfulagent.com

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Table of Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Prince Ivan and His Horse

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

The House in the Wood

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

A Song Unwisely Sung

Chapter 14

Part II

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

The Building of Skadar

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Part III

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

The Queen of the Owls

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

The Goatherd, the Vila, and Her Death

Chapter 39

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Allison Epstein

To Grandma Ida,with love

One must believe in the possibility of happiness, and I now believe in it. Let the dead bury the dead; but while I am alive, I must live and be happy.—LEO TOLSTOY, WAR AND PEACE, TRANS. LEO WIENER

Part I

FIRST FROST

1

Sasha

These woods would have run wild, if they’d been allowed to. Not far from here, the forests owned the land—tangled trees, ground rooted up by wild boars and badgers, vegetation-choked lakes that stories said were home to wicked spirits, because what else could thrive in water so black? But the woods outside Tsarskoe Selo were the tsar’s woods, and anything belonging to the tsar meant order, regularity, precision. It was winter now, but all year round these trees were as pristine as if a Dutch master had painted them. The only thing out of place was Aleksandr Nikolaevich, who knew he was as far from imperial splendor as it was possible for a man to be.

Long stretches of frozen track and heavy drifts made the trek from Saint Petersburg slow going, and because Sasha’s horse was property of the Imperial Army, he’d been forced to leave it at the final outpost and take the last fifteen miles to Tsarskoe Selo on foot. He’d intended to trim his beard before leaving camp, but that hadn’t happened either, and so he looked as bedraggled and ill-prepared as he felt with each step nearer to the Catherine Palace. What would Felix think of him, when he stumbled into the grand halls of the imperial estate? Hardly a celebrated hero returning from the wars. A vagabond, rather, begging for a place to stay.

The war was over, Napoleon and his Grande Armée fleeing west pursued by a determined force of regulars who would snap at their heels all the way to Paris, but no one had told Sasha’s nerves. Every sense was pricked for anything amiss. The trill of a bird. The creak of tall firs, dusted with snow and ornery with cold. The wind, muffled and hollow through the worn fur of his hat. No sign of danger, not yet, but that was the trick about danger; it seldom gave a sign. The fighting at the end hadn’t been like it was before, at the blood-soaked field of Borodino, the disastrous losses at Austerlitz, but it would take more than the retreat of the French emperor to convince Sasha that this was, in fact, a time of peace.

A gap between the trees, and the gilded roof of the Catherine Palace rose through the dusk, bright enough to make Sasha’s heart shudder. Its burnished domes were like a cathedral in the wilderness, glittering against the robin’s-egg walls. After so long at the front, the palace seemed like a dream, some fantasy one of Felix’s cooks would spin from sugar and marzipan. Another step, and it was gone, lost in the leafless tangle of branches. Beautiful, but insubstantial. It seemed impossible that such a delicate structure could exist in the same world where the roar of cannons rattled men’s teeth, where the choke of gunfire blotted out the sun. He kept to the path, forcing his thoughts down a different track. A warm fire. A chance to unlace his boots. A smile from Felix, the sound of his voice, not a dream of it but the reality, the true color of which could never be recreated, not even in the most faithful memory. He sighed at the thought, the thick cloud of his breath catching in his hat like frost. I told you I’d come back in one piece, he’d say to Felix, when they were alone. It takes more than a war to keep me away from you.

Then he stopped.

Without the crunch of his footsteps, the silence was total. And yet he was certain he’d heard something. A small thump. Muted, like a body falling into the snow.

The idea was nonsense. Forests made noises. Snow fell from tree branches. Birds shook dead twigs loose. Badgers raked their claws along tree bark for food to bring back to their setts. He’d been moving since dawn, that was all. Sit down, get something to eat, and the world would start to look like itself again.

The next sound was a soft exhale, distinctly human and not his own.

Sasha looked off into the woods. The woods looked back invitingly.

It wasn’t late, but dusk fell early now, and soon it would be dark in earnest. And while he no longer believed the midwinter stories his mother had told around the stove when he was a child, there was still no cause to go looking for trouble. Men weren’t meant to walk through woods alone, even manicured woods like these. Too many threats could lurk in the shadows: the scale-crusted vodyanoy, snatching travelers from the banks of its lake to gnaw on their bones beneath the surface; long-haired rusalki, ghostly women luring men to their graves to avenge their own deaths. Nonsense and superstition, fairy stories to keep children indoors after dark, but nightmares didn’t die as quickly as belief in them did.

Still.

That breath again, and this time a soft groan. A woman’s voice.

Sasha crossed himself and cut sideways into the woods. Despite his better judgment, curiosity remained like the itch of a healing wound, more insistent until every nerve twitched against it. Some instinct—what, he couldn’t have said—insisted that whatever had happened here, it was his responsibility.

It didn’t take long before the trees opened into a clearing ringed with tall pines. In the center, he saw a woman, lying on her side in the snow.

Had it been any darker, he’d have missed her entirely. Her long, thin coat was the same shade as the snow; in the dying light, she resembled a disembodied head and pair of hands lying in the powdery drift. Her hair covered most of her face, and it was not gray or blond but white—not the white of age, but of feathers, of sun reflected off a frosted window. She lay as if she’d fallen from a great height, one cheek pillowed against the snow.

Sasha’s mother always said a vila could change her appearance at will. Cunning spirits of the forest and the air who could assume the female form most pleasing to the man they meant to trap, sharp laughter ringing as they rent their prey to pieces. He looked up, half expecting to see a grinning demon with silver eyes leering in the branches overhead. But his view to the sky was unbroken, pale gray shot through with red, minutes from sunset. The woman in the snow seemed to shimmer in the fading, otherworldly light. Was this what the painted angels in Petropavlovsky Cathedral would look like if they fell to earth?

A fallen angel, he thought grimly, and yet to his knowledge one angel in particular was famous for making that fall.

The figure shivered, and suddenly she was no longer a fiend, but a woman in need of help. He flinched, thinking of the boys in tattered French uniforms he’d seen lying on the Smolensk road, flesh blue and frozen stiff. He had witnessed enough of that and done nothing—but this was peacetime, this was different. And if Felix’s first glimpse of Sasha in months cast him as this poor woman’s savior, there were worse impressions to make.

Snowdrifts reached well past his ankles as he forced his way toward the woman. The thick boots of his uniform were ideal for heavy wear, but no clothing in the world was suited for a jaunt through uncleared snow in December. Damp and cold, he knelt beside her, ignoring the wet shock as the snow met his knees. The curtain of hair still obscured her face. He reached out a gloved hand to brush it back.

Her skin, what he could see of it, was nearly translucent and tinged with purple. She barely moved against his touch, but he could see no lacerations, no bruises, no broken bones, and her breathing was easy. He gritted his teeth, then shrugged off his overcoat and draped it over the woman, allowing winter to pierce the weave of his uniform. Lifting her was easier than he’d expected, as if her bones were hollow. As he forged a path back to the road, the woman’s heartbeat matched his, seemingly sympathetic to his shivering. In a few minutes, they’d both be inside, a soldier and a stranger in a palace of royals. What happened after that was outside his control, and things past control were past concern.

Soon the woods gave way to cleared paths and neat grounds, carefully manicured beneath the snow. He held the woman close and quickened his pace toward the Catherine Palace, that great hollow building with its five spires catching the last flares of the sun. Marzipan dream. Gilded prison. Either way, warm, and out of the wind.

The woman stirred in his arms; in shock, he nearly dropped her. It had only been a twitch, but that was enough. Alive enough to move. Thank God. Entering the palace holding a corpse wasn’t the effect he’d been aiming for.

“It’s all right,” he said under his breath. “We’re nearly there.”

The woman gave a soft hum and cracked one eye open, the lashes barely separating. One golden eye. A rich tawny yellow, bright as a coin.

He blinked, and her eyes were closed again, pale lashes against lilac skin. The inhuman color was gone, as if it had never been.

Because it had never been. Now was not the time to let his imagination run wild. Without his coat, the cold set in deep. He could feel his numbed hands falling slack around the woman, threatening to drop her at any moment.

When he kicked the side door in lieu of a knock, it gave way at once, which annoyed Sasha but did not surprise him. For all that he was the younger son of the tsar, Grand Duke Felix was startlingly lax in matters of personal safety. If Felix hadn’t left every door of the palace open in Sasha’s absence for robbers and brigands to stroll through and help themselves to imperial heirlooms, he supposed he should count himself lucky. Sasha set off in the direction of Felix’s private apartments. At the very least, he’d find a servant there to direct him. And to lock the door behind.

The Catherine Palace was the same as when he’d last seen it six months before, and for a hundred years before that. Time moved slowly for the imperial family, however quickly it passed for their subjects. Take a stroll down Krestovsky Island in Petersburg where Sasha had grown up, and barely one building in twenty was older than he was. Homes and taverns and shops bloomed and died like crocuses, progress cycling through and leveling anything that had outlived its utility. But this hall hadn’t been altered since the last tsar had walked through it, or the tsarina before him. Polished mirrors capped with gold, marble floors, portraits of severe-looking men draped in military medals looking down their noses at Sasha and the woman. Avoiding their eyes, Sasha watched the gentle ripple of the woman’s breathing instead. He was thirty-one years old, and yet the disdain in these paintings made him feel like the awkward youth he’d been when he’d first seen the imperial family, a new cadet with an ill-fitting uniform and hungry eyes. His boots left heavy prints of mud and snow along the marble, but that would be a servant’s task to deal with later. This garish palace could stand a brush of something natural.

Around another corner, Sasha at last came upon a footman, who stopped in his tracks with wide eyes and his mouth half open. Evidently he hadn’t expected an army captain and a half-dead woman to let themselves in at this point in the evening.

“The grand duke?” Sasha said tersely.

The footman blinked, taking in Sasha’s uniform, his familiarity with the palace, how little good arguing with him was likely to do. “With the musicians,” he said.

So this was Felix’s idea of security without Sasha to direct him. God grant him patience. “And where are the musicians?”

This second prompting seemed to jar the footman back to himself. “In the east parlor. Do you require—”

“No,” Sasha interrupted, already setting off. “I know the way.”

The footman, thankfully, did not pursue him.

Each step along the marble floor soured what remained of Sasha’s hopeful mood. It had been foolish to expect a private audience, but when he’d pictured this homecoming, he’d allowed his imagination to get the better of him. More than once, he’d dreamed up the scene: Felix would be alone in his bedroom, absently watching the snow fall through the window, only to look up at the faint sound of Sasha’s entrance. The distance separating them would shrink to nothing, and Felix would be in his arms again, and they could fall together into bed for as long as they chose to stay there. It was a pretty thought, but not worth the minutes he’d spent dreaming it.

Because the door to the east parlor was in front of him now, and though he could not see inside, the door was ajar, and he could hear. The careless dance of two violins in harmony, playing with more finesse than Sasha had heard in months—since the last time Felix had brought in a band of musicians from Petersburg, no doubt. And there, above the complex weave of the music, a tangle of voices, raised in song and smoothed along the edges with drink. One voice that, even in a chorus, Sasha would recognize anywhere.

The woman nestled closer against his chest, as if to remind him of her presence. He shivered, imagining long hair, cold fingers dragging him through a crack in the ice, in the earth. The sooner this woman wasn’t his responsibility, the happier he’d be. And if that meant interrupting this band of midwinter idlers, so be it.

Without the benefit of his hands, Sasha shifted his balance, then kicked the door open.

As if they faced such interruptions every day, the musicians didn’t miss a note. They were scattered across the parlor as if it were any peasant barn or bonfire, their unhandsome faces alight with drink. Beyond the violinists Sasha had heard from the hall, there was a young woman with a clarinet and a boy of perhaps fourteen with a hand drum, who alone looked up as Sasha entered. A grand brocade sofa sat near the center of the room, with two beautiful women sprawled along it, their skirts vibrant and their cheeks flushed, voices raised in song. One, the blonde, had a near-empty glass of wine in her hand. The other, the dark-haired one, sat on Felix’s lap, trailing one finger through his hair.

Sasha had hoped—had feared?—that the tsar or the tsarevich or the pressures of wartime would finally have forced the grand duke to grow up. But no, this was precisely the same Grand Duke Felix he had left. Tall, strong shouldered, and slim waisted, he still looked like a storybook prince, his pressed jacket slung over the back of the sofa and his cobalt-blue waistcoat carelessly unbuttoned. When Tsar Sergei had banished Felix from Petersburg to Tsarskoe Selo two years ago, the understood intent had been to cool his son’s wayward spirit, or at least shame him with a taste of exile from the business of the capital. What he had done instead was give Felix a pleasure garden and the privacy to make the most of it. Sasha could have laughed, if not for the weight in his arms, and the curious twist in his throat as the dark-haired woman’s fingers trailed down Felix’s cheek.

Jealousy was familiar territory for Sasha, but Felix had always lacked the insecurity needed to comprehend it. The moment he caught sight of the curious pair in the doorway, Felix’s dark blue eyes flashed with delight, and he extricated himself from the tangle of limbs on the sofa.

“Sashka!”

The musicians stopped playing and turned to Sasha, standing there awkward and unannounced with a half-dead stranger in his arms.

“Sashka,” Felix repeated, slightly puzzled now. “And you’ve brought a wife with you. Good God, war has changed you, hasn’t it?”

The woman shifted in Sasha’s arms, and her hair fell away from her face with the smooth movement of water poured from a height. “Be serious,” he said, and he was briefly thankful that if he couldn’t get Felix alone, at least he’d come upon him in this careless company, a time and place where he didn’t need to bow and murmur “Your Imperial Highness” like any common man called before a Komarov. “Help me, would you? She needs a doctor.”

“Who is she?”

“How should I know that?” Sasha said tersely. “I found her on the grounds.”

“Aleksandr Nikolaevich, model of Christian charity,” Felix drawled. “I’ll recommend you for sainthood.” Authority blended with amusement as Felix gestured at one of the violinists. “Right then. Arkady, you can hold a person as well as an instrument, can’t you?”

“So I’ve been told, Your Highness,” the musician said with a wink, earning a laugh from the women on the sofa and a blush from the clarinetist.

Felix grinned. “Good. Take her to the bedroom at the end of the corridor. And send for my physician once you get her warm. We’ll want to know who she is and how in hell she wandered into my park, but that’s a question for tomorrow.”

“Yes, Your Highness,” Arkady said, as Sasha carefully transferred the woman to him. Sasha’s arms seemed to hover beside him, suddenly unburdened by the weight. He watched as Arkady carried the woman away, in search of a soft bed and a safe place to rest. He’d done his duty, but even so, he didn’t like the idea of turning his back on her.

“And you,” Felix said, spinning Sasha around to face him. All thoughts of the woman vanished with the warmth of Felix’s hand on his forearm, and that brilliant smile. “Well done, you. I suppose you’re the one to thank that Napoleon turned tail and ran.”

Sasha frowned, tasting gunpowder. “General Kutuzov won’t like you giving me the credit, Felya.”

“And when have I ever cared what that swaggering drunk likes?” Felix said, and God help him but the gleam in Felix’s eye seemed even wickeder now. That rumpled waistcoat, and his dark hair messy, and his attention fully, entirely, intoxicatingly on Sasha. “You’ve just won a war, Sasha, and saved a helpless maiden besides. Let me embellish a little. Enjoy the fairy tale for a night.”

He led Sasha toward the sofa, which the two women had already vacated. Their job was not to seduce the grand duke. It was to make sure Grand Duke Felix had everything his heart desired. And tonight—as Felix guided Sasha down onto the cushion and sat beside him, his mouth so desperately close to Sasha’s throat—what Felix’s heart desired was Sasha.

“Where are your manners, you good-for-nothings?” Felix said to the musicians, though the jab had no bite in it. “Get the hero something to drink.”

The softness of Felix’s fingers. The sight of Felix’s brilliant grin. The familiar chill of a glass pressed into his hand. It wasn’t at all how Sasha had imagined his return.

Not that he was complaining.

2

Felix

Felix woke late the next morning with a dry mouth and a headache. He gave a soft, irritated mumble and rolled over to nestle against Sasha’s shoulder. Effects of last night’s drinking notwithstanding, he intended to enjoy waking up this morning, and that meant making it last. It had been ages since he’d shared a bed with Sasha, and he’d missed it, the solidity of the soldier’s body against his own. His bed hadn’t stayed empty that whole time, of course, but there was a safety in Sasha’s presence that no countess or courtier had been able to match. Those encounters had been entertainment; Sasha in bed beside him was home.

“You’re impossible,” Sasha murmured, though he did not push Felix away.

The vibrations of his voice rumbled through Felix’s body like a wild horse. “I beg your pardon. I have it on good authority that I am a delight.”

Sasha hummed, though if the way he carded his fingers through Felix’s hair was any indication, he didn’t entirely disagree. “I missed you, Felya,” he said, his voice still more sensation than sound.

There was such comfort in being held like this, by someone who would tease him with one breath and kiss him with the next. Sasha’s broad shoulders looked like granite against the fine sheets. “Nonsense. All those rugged grenadiers in those fine, tailored uniforms, you must have been in heaven. I’d be surprised if you had half a thought to spare for me.”

Sasha scoffed. “And I suppose you and your harem of musicians were all sitting with your noses pressed to the window pining.”

Felix laughed. “Come now. If I’m to be judged by what I say and do, there’s no hope on God’s earth for me.”

He sat up and ran one hand through his hair, letting the sheet fall to his hips. Sasha mirrored the motion as if by instinct, keeping the distance between them the same. All the while, Sasha’s eyes never left him. It was a beautiful, shining sensation to be seen like that, not as the disgraced son of the tsar or the lord of the Catherine Palace but as Felix, a man of twenty-eight with a sharp wit and a zest for grandeur. He’d forgotten, when Sasha left for the front, how much he loved being seen this way. He cupped Sasha’s cheek in one hand and leaned in to kiss him, soft and slow and careless.

“Do you know what I’d like to do this morning?” Felix said. His lips were still very near to Sasha’s, and he enjoyed Sasha’s shiver like an actor accepting applause. “I’d like you to stay right here with me. We have months of lost time to make up for.”

Sasha smiled, which felt like a success. But then he swung his legs out of bed and reached for his shirt, which felt like a categorical failure.

“That is the precise opposite of what I just said, Sashenka.”

He didn’t stop, though he did laugh. “You ought to come spend a week with my regiment. It’ll teach you that sloth is a vice.”

“I know it is,” Felix said, folding his arms. “I’m collecting vices. Trying to complete the set. Come back to bed.”

“You have a guest, Felix.”

Felix cocked an eyebrow at him. This was no time of day for riddles, even without the lingering headache. “What, do we expect a visit from the American ambassador? Mr. Adams can wait until we’re finished. Or he can join us if he’s so terribly eager—”

“Felix,” Sasha interrupted. His expression was severe, but Felix could tell he was trying not to laugh. “That woman.”

Ah. Felix had forgotten the unconscious stranger Sasha had brought back to the palace the night before. An enthusiastic homecoming celebration had a way of overshadowing such details.

“I’ll bet you fifty rubles she’s sleeping,” he said. “The state she was in? And unless you’re encouraging me to loom over strange women while they sleep like some kind of night demon …”

Sasha had fully dressed by now. The morning sun caught him through the window in the corner, making the trim of his jacket gleam. His black eyes and sober expression made him look like an icon hung for worship, and about as easy to argue with.

“Trust me, Felix,” Sasha said. “I don’t think you should leave her alone.”

“You sound like my nurse,” Felix muttered, though he did lean over the side of the bed for his trousers. “Afraid of the women in the woods. Are you going to tell my future in the mirror next? Drop some candle wax in a pitcher and see who I’ll marry?”

“I’ll come with you, if that will get you out of bed faster,” Sasha said. “Or I could leave you to do it yourself and see whether any of those handsome grenadiers are stationed in the village—”

“All right, I’m coming, stop hectoring.”

* * *

Felix sent a maid ahead to the east bedroom to alert the stranger to their presence and give her a chance to dress properly. The necessary nod to formality had additional uses: it gave him time to splash his face with cold water and send for a servant, who returned with enough scalding-hot tea to chase away the worst of the fog still drifting about his brain. Sasha remained near the doorway while Felix made himself presentable, watching the production solemnly. Felix, who had never once objected to an audience, made no effort to hurry.

At last, the maid returned and, with a faintly alarmed look at Sasha, led them to a small sitting room at the far end of the corridor, where the woman was already waiting for them.

She sat in an armchair beneath the window, her legs tucked up beneath her, watching the falling snow. The posture gave her a curious look: small but not weak, like a coiled animal before a strike. She wore a simple navy-blue gown with cap sleeves and a square neckline—something the maid must have unearthed from deep within one of the palace’s unused wardrobes, as Felix didn’t recognize it as anything he’d lent to other women who’d stayed the night. The color became her, throwing into relief the strange gold of her eyes.

In the clear light of both morning and sobriety, there was no denying it: she was the most beautiful person he’d ever seen. Striking in a categorically different way than Sasha was, like trying to compare a deep-rooted pine and a flash of lightning. He wasn’t one for embarrassment, but Felix felt the blood rush to his face looking at her, this remarkable woman who sat in his chair like a snake, waiting for him to speak.

“You can come in, Felix,” she said.

Startled and not a little embarrassed, Felix took a step forward. For the way she’d addressed him, “inappropriate” was an understatement. The correct form of address was “Your Imperial Highness,” followed by a deep obeisance that would connect her forehead with the ground. She threw out his given name without thinking, the way Felix might address a servant. Something twitched within him at this—anger, at first, and then something else, rich with excitement and utterly forbidden.

“Obviously,” he said. “It’s my house.”

He sat on the edge of one of the upholstered armchairs opposite her, leaning back onto his hands. Sasha remained near the door, his hand at his belt where his pistol would have been. For all he had treated it lightly before, there was no question, Sasha was afraid of this woman. In her presence, it was easier to see why.

“You may go,” the woman said, dismissing the maid with a wave of her hand.

The maid stared, clearly stunned at the notion of leaving a woman unchaperoned with two men. She was hardly alone: Sasha looked positively indignant about it. Then again, Sasha could be indignant if a horse in the palace stables looked at him rudely, so long practice made that easy to ignore. And Felix had to admit, the woman’s boldness had caught his attention.

“You heard the lady,” he said, nodding to the maid, who closed the door behind her with great trepidation. Alone now, Felix cleared his throat, though the cough sent reverberations through his headache. “I hope you slept well, mademoiselle,” he said politely. “You looked as if you could use it last night.”

She rested one elbow on the arm of the chair. “Yes. Thank you for the valiant rescue.”

“It’s Captain Dorokhin you should thank,” Felix said. “He’s the one who pulled you from the snow.”

Captain Dorokhin, from the door, seemed to be sincerely regretting that decision.

“Do you have a name?” Felix asked.

“Sofia Azarova.”

Felix regarded her with his head tilted. “And what exactly were you doing in my woods, Sofia Azarova?”

Sofia shrugged, rustling the soft fabric of the gown. “I am sorry about arriving unannounced,” she said. “I’d have called on you properly, but the journey was more difficult than I thought.”

This had not answered his question. “Because you flew here, I expect,” he said waspishly. “And fell out of the sky.”

“Your Highness, if you want her gone, I—” Sasha began.

“Not yet,” Felix said, raising one finger. He leaned forward, resting his palms on his knees. Sending her away would have been safer, but something in her had sunk its claws into him and refused to let go. It was so rare, in his position, to find a person whose next move he could not predict. “I’ve been patient with you until now, mademoiselle, but if you’ve forgotten who you’re speaking to, I’m happy to remind you.”

“I know who I’m speaking to,” she said. “I wonder if you do.”

Felix’s eyebrows arched. “I have some ideas,” he said, striving to imitate the dry detachment with which his father received petitioners. “A peasant girl. A charlatan. Someone trying to work her way either into my bed or my purse, or both if she’s lucky.”

“That’s not quite how I’d put it.”

“You tell me, then,” Felix said. “I don’t have time for games.”

Sasha took a step forward, with the apparent intent of removing Sofia bodily from the room.

But Sofia only smiled. And then the corner of her mouth wasn’t all that moved.

The casement window flung open behind her, as if a hand had seized it from outside and pulled. Cold, piercing and immediate. Felix leapt to his feet and scrambled away as curls of snow thundered into the room, translucent and untamable. Had it even been snowing a moment before? He couldn’t recall. Couldn’t think of anything but the snow that danced and swirled in tight spirals before settling on the imported carpets, dusting and melting against the candle flames. And at the center of it all, Sofia Azarova. The wind caught her hair and sent it fluttering like a saint’s aureole. Her golden eyes, flashing.

The sound that escaped from Felix was very nearly a scream. His body moved on its own, scrabbling backward like a grasshopper, nearly tripping over Sasha. The woman might have leapt from the chair and torn out his throat. Instead, she let out a soft laugh. The floor under Felix’s feet trembled with the force of his heart.

Power. The marrow of his bones knew the feel of it, and the roots of his hair. He knew it as surely as he knew anything.

And then, as suddenly as the storm had come, it was gone.

With one last swirl, the snow lost its momentum and settled to the floor in a soft powder. The window banged against the frame, once, then once again, and stilled. Sofia’s hair fluttered, then drifted to her shoulders just as it had been, not a strand out of place. Merely a woman dressed in a borrowed blue gown, perched on a chair that now reminded Felix of a throne. She said nothing. Waiting for a response he wasn’t sure he’d ever be able to give.

“You can shut your mouth, Felix,” she said drily.

Felix snapped his jaw shut. His boots crunched against snow as he stepped forward. “Who are you?”

Sofia grinned. “That’s hardly a polite question to ask a lady.”

“Felix,” Sasha began, reaching toward Felix’s shoulder, “I wouldn’t—”

“Yes, I know you wouldn’t,” Felix said, shrugging him away. “Mademoiselle Azarova, you can stay at Tsarskoe Selo for as long as you wish. I think we have a great deal to talk about.”

“Thank you,” she said, in the tone of someone who hadn’t been waiting for permission.

“If you need a chambermaid to help you with—” Felix began, ignoring Sasha’s indignant splutter at the idea of giving this stranger access to servants.

But Sofia cut him off. “No need,” she said. “After long enough making do for myself, I prefer it that way. But thank you for offering. It’s kind of you.”

Felix nodded. He should, he knew, have had any number of reactions. Confusion, the kind of horror that would immediately precede his running from the palace grounds and never looking back. What he felt instead was fascination. A hint of fear. And beneath that, a hunger. Not for this woman, not precisely. But a hunger to know her—to understand her and her command of the world.

“Of course,” Felix said, with a small bow. “You should rest, mademoiselle. Might I come speak with you later?”

He couldn’t remember the last time he’d asked permission of anyone for anything, let alone entering a room in his own house. Still, he felt an unaccountable relief when Sofia nodded. “I’ll take a walk later, I think,” she said. “Explore the house, build my strength back. But this evening I’d be happy to talk further.”

“By all means,” Felix said, before Sasha could protest. “The Catherine Palace is at your disposal until then. Come on, Sasha. Let’s leave her be.”

Sasha glowered at Sofia, then turned on his heel and left. His boots left firm prints in the snow covering the carpet. Behind him, the storm continued to swirl beyond the window, shadows of white against the glass, directed by God knew what.

* * *

Felix closed the door, his blood like lightning. Despite the door between them, he thought he could still see Sofia, those sharp eyes looking into him, past him, through him. Even if their encounter had been mundane in every respect, he’d have known there was something different about her, something special, from those eyes.

“I’ll call the guard,” Sasha said, turning to go.

Felix shot out a hand to stop him. “What?”

Sasha pulled away so fast Felix flinched. His disbelief was as complete as Felix’s own. “You saw that. Don’t you see what she is?”

Through the window on the opposite side of the corridor, the snow fell faster than ever. Felix could hardly see the park through the cloud of white. It was as if the sky itself had come down to Tsarskoe Selo, claiming the palace and everything inside as its own. It was impossible that she’d called up this storm, but the thought presented itself regardless, insistent.

“What is she, exactly?”

Sasha swore. “I don’t know, but it’s not natural. You know the stories. The vila, the rusalka, witches and spirits. What she’s just shown us isn’t half of what she can do. It’s too dangerous to let her stay here.”

Felix stared. “Are you mad?”

Sasha squared his shoulders, and in a moment he was an army captain again, not the grand duke’s lover, not a frightened peasant startled by a storm. There was a way of standing when you wanted your orders to be obeyed. There was a way of speaking when you expected your audience would pay rapt attention. Felix had been raised in the imperial family; he knew them both. Sasha had led soldiers to their deaths; he knew them, too.

“Don’t laugh at me, Felix. I know what I saw.”

A witch. Here. In Tsarskoe Selo. If not for the deathly seriousness in Sasha’s posture, Felix would have thought the captain was joking. Some ancient spirit of the land or sky that drew her power from the forests and mountains and lakes, who could magic herself into a great predatory bird and with a word control the snow and the lightning. A spirit who had chosen heroes among the ancients and given them gifts of glory beyond measure. A cruel queen who betrayed her heroes, soaring away over the woods, leaving scorched earth and bone behind. Resting in one of the unused sitting rooms in the Catherine Palace, wearing a spare gown, while below the kitchen staff determined the menu for supper.

“Sasha. Listen to yourself.” He laid one hand on Sasha’s shoulder. Sasha flinched as though at a great weight. Aleksandr Nikolaevich, the fearsome captain of the Sixth Corps, afraid? “She’s different, I’ll grant you that. But I thought we all gave up believing in witches when we were children.”

The soft edges of fear in Sasha’s eyes hardened. He stepped back, broad shouldered and heavy browed, his familiar face cold and unyielding.

“I don’t trust her. Send her away.”

Felix hesitated. He’d known of her existence for less than a day. He could send her off and return to the beautiful comfort of this morning, with Sasha’s fingers tangled in his hair, content and untroubled. The war was over. There was no reason to create new battles out of nothing.

He opened his mouth to agree, but a different answer came out, the one he’d known deep down he would give.

“No, Sasha.”

“But—”

“She stays. That’s all.”

The authority felt strange on his tongue. He rarely flaunted his power, detested the way his father and brother wore their rank like an ermine mantle. But he was second in line to the imperial throne, and in this, he would settle for nothing less than having his way.

Sasha’s expression melted away, and he turned and left Felix alone in the corridor. As if he couldn’t trust himself not to say what was on his mind.

It wasn’t too late for Felix go after him. Soothe the hurt he’d caused, make it right. Send Sofia away to make peace and then later, when their nerves had settled, persuade Sasha to tell him what had frightened him so deeply, what superstition had leapt from the heart of such a practical, levelheaded man.

Felix glanced once more at the closed door separating him from Sofia. With that look, he was decided. Sasha’s hurt feelings could wait.

The captain was, suddenly, no longer Felix’s most interesting companion at Tsarskoe Selo.

3

Marya

Fifteen miles from the Catherine Palace, in a cramped neighborhood where the Neva split Petersburg like a seam, Marya Ryabkova leaned against the pane of the second-story window and kept a sharp eye on the street. Behind her, Isaak worked at breakneck speed, his thin body bent over the printing press like some sort of fantastic insect. Another copy of the pamphlet they’d spent two weeks rewriting emerged from the press, the close-set type bold against the page. Two hundred copies, they’d decided that morning before setting out. Two hundred would be enough to get their message in front of the Petersburg citizens most likely to respond to it: students, shopkeepers, soldiers fresh back from the front, the drivers and messengers and menial laborers whose bent backs kept the city breathing. Those two hundred would tell two hundred more, and before the week was out, the Koalitsiya’s message would have spread like wildfire. Yes, some would ignore it, caught up in the wave of patriotism the tsar had nurtured throughout the war. But others would see that the fabled prosperity of Russia spent more time at certain men’s tables than it did at others’.

And those people—the ones who saw matters the way they did—might be ready to seize the moment.

“Divide them in half once you’ve finished,” Marya said, glancing back at Isaak. “You can start at the harbor and work east. I’ll start by the Haymarket.”

Isaak grunted, whipping another printed copy from the press. “When did you start giving orders?”

“The writing was your job,” she answered, “just like the speaking will be. Let me do the one thing I’m good at.”

Isaak rolled his eyes but didn’t argue. The words they would distribute today had flowed from Isaak’s brain to the page with only a layer of polish from his fellow members, spinning a rationale for the proposed general strike so compelling it had stirred Marya’s blood, even though they’d discussed almost nothing else for weeks. His speech at the upcoming rally would do even more to win hearts than the printed words could. He would bring the patchwork collective of discontented citizens together under the Koalitsiya’s banner with a skill that was his alone, uniting them around the cause: legal protections for workers and peasants, a reformed imperial council, religious freedom, a clear path to emancipation for the country’s twenty million serfs. But the way he knew the cause was the way Marya knew Petersburg. Its streets were as natural to her as the flow of blood through her veins. She hadn’t earned her place at Isaak’s right hand by having nothing to contribute.

Down in the street flashed the green of a familiar uniform.

“Soldiers,” she said sharply, easy banter forgotten.

Isaak swore. In a moment, he’d rolled what pamphlets they’d printed into his satchel, while Marya sent the movable type scattering like mice across the floor. They’d kept the pamphlet short, as most of their audience could read only with difficulty, but a single page had the added benefit of being easier to hide. Tracks covered, Marya peered through the window, checking the progress of the soldiers. Six uniformed members of the Semyonovsky Life Guards Regiment stood outside the door to the printshop. The first had already taken a step up the stairs.

Marya locked the door to the staircase, though it wouldn’t hold for long under pressure, and turned back to Isaak. It wasn’t the first time they’d found themselves with armed soldiers too close for comfort, and she allowed a clear-eyed focus to shove away her fear. They were in danger, but she could manage it. If she moved fast.

“How did they find us?” she said, though her attention was already focused on escape routes.

“The same way they find everyone,” Isaak said grimly.

Technically charged with maintaining order in the city, the Semyonovsky Regiment, like Ivan the Terrible’s oprichniki before them, had one task that rose above the others: to track down opposition aided by a scent on a breeze, a single footprint in the snow, a suspicion and nothing else at all. More pernicious than any fairy-tale monster, a multiheaded dragon with ears in every wall. The regiment might have had informants placed in any den in the city, any traktir or market or back room where the Koalitsiya dared to meet. Of course Marya and Isaak had been found. It had only ever been a matter of time.

The locked door shuddered under the kick of a booted foot. In moments, Marya and Isaak would be face-to-face with at least seven soldiers, armed to the teeth and under orders to shoot those deemed traitors on sight. The dozens of pamphlets in his satchel would only seal their death sentence. Isaak had an old dueling pistol tucked into the pocket of his greatcoat, and Marya’s hunting knife hung where it always did at her waist, but the tsar’s men were trained from the cradle to kill when orders commanded. If it came to a fight, it wasn’t one Marya and Isaak expected to win.

The second dirty window at the back of the room hadn’t been opened in years, judging by the unbroken layer of paint that splashed across both sill and glass. Still, desperate times.

“Stand back,” Marya said.

“What—”

With the birch handle of her knife, Marya struck the center of the window, smashing the cheap glass into tiny shards. Her knuckles hummed with pain from a dozen small cuts, but there would be time in the future to worry about those. Punching out the remains of the window with the knife, she unwound the long scarf that covered her hair, then secured one end to the window sash. She could feel, from a great distance, her mother’s weary disapproval—A respectable woman of your age never goes bareheaded in public, Masha, think of your reputation—but if Vera Ryabkova had known the full extent of her daughter’s activities with Isaak Tversky and the Koalitsiya, proprieties of dress would have been the least of her worries.

“God in Heaven, Masha—” Isaak began.

“Watch your hands,” she said, climbing through the window. Holding tight to the scarf, she braced herself against the wall some fifteen feet above the alley below. It wasn’t an impossible drop, and the scarf would help her belay down partway. She took a careful step, then another, feeling the grip of the wall through the soles of her boots.

Just above her, the door gave way under a soldier’s rifle. Isaak scrambled through the window, and Marya, startled by the quavering of her makeshift rope, let go.

She hit the ground hard and rolled, swearing loudly. She hadn’t broken anything, as far as she could tell, but there would be a bitter bruise on her hip come morning. Isaak kept his feet through the landing and extended a hand to haul Marya to hers. Behind them, Marya’s scarf fluttered like a pennant of war, urging their next move.

A tactical retreat. And quick.

“Go,” she hissed, jerking her head toward the river. Isaak had always been the faster between them. If he left her behind, he could get out of sight before the soldiers—no doubt already aware their quarry had given them the slip—formed an organized pursuit. And the Koalitsiya needed Isaak more than it needed her. She had long ago decided how much she was willing to give for the cause.

“Don’t be a hero, Masha,” Isaak said. “That’s my job.”

He dragged her down the street. Each step in their halting run made her grit her teeth in pain, but she refused to slow. She knew what would happen if the soldiers caught them; they both did. A cell in the Trubetskoy Bastion, where men whose life’s work was making others talk would coax out every last secret they possessed. Where the Koalitsiya made its headquarters. Which members made up its ranks. Who spoke on behalf of the dockhands, who for the discharged soldiers. How their forces were organized, how news passed from one member to the next, how far they were willing to go. There was no question how it would end: with every soul that had ever so much as thought the word Koalitsiya buried in a shallow grave on the outskirts of the city, the ground too frozen even for carrion birds to peck through.

They cut sideways through an alley and emerged onto Kronverkskiy Prospekt, a wide boulevard glittering with the fading afternoon light. Citizens went about their business on both sides of the snowy street, their bodies swathed in rich furs and heavy fabric. One or two sent a disapproving glance toward Isaak and Marya—a young woman in the company of a man, unchaperoned and bareheaded, limping, blood dusting her knuckles, would be a scandal in most neighborhoods—before turning up their noses and keeping their distance. Their sneers meant nothing to Marya. At present, the only thing she cared an inch for was the sledge driver guiding his horse south down the boulevard, bearing a paltry load of root vegetables.

Isaak, spotting it at the same moment, raised a hand to hail the driver, but Marya was faster. She put two fingers in her mouth and let loose a piercing whistle, sharp enough that the horse nearly skidded to attention. The driver glanced their way, his beady eyes suspicious beneath his wolf-pelt hat.

“I don’t run a charity service, devushka,” he said coolly. “You keep to your business, and I’ll keep to mine.”

“Preobrazhenskaya Square,” Marya said, hauling herself onto the open back of the sledge and watching Isaak clamber in after her. “Please. We’ll pay double if you’re fast.”

That was all it took. The driver flicked his whip, and the sledge took off down the icy boulevard, leaving the district and their pursuers behind.

Marya slumped down against a wooden crate of what seemed to be turnips, her chin practically resting on her breastbone. Everything hurt. She’d be limping for days, and her heart still had not resumed its usual pace. Even the edges of her vision had begun to shudder, and she wondered if she might faint. But they were free.

Away. And they’d achieved what they set out to do.

Beside her, Isaak reached into his satchel and produced a single copy of the pamphlet, with which he gestured at the driver.

“Think our new friend is interested in a strike?”

Marya looked at him in disbelief for three uninterrupted seconds. Then, with the near madness of two people who had been until recently running for their lives, they both began to laugh.

* * *

They left the driver with a sum of money twice as large as either of them could readily afford, along with a copy of the pamphlet for good measure, then set off. Their destination was several minutes’ walking from where the sledge had left them, but they knew better than to lead anyone to the Koalitsiya’s current sanctum, even someone as seemingly powerless as a driver. Everyone in Petersburg talked. Let one fact slip, and in three days there was no telling who else might know it.

“You’re all right?” Isaak asked, watching her hesitant steps.

Marya winced. “Oh, just grand,” she muttered. “Come here.”

He offered her an arm, and she leaned heavily on him, letting his thin frame take half the weight off her leg. This close, she could sense the tension in his jaw and the firm set of his shoulders. Their narrow escape had shaken him, and it touched her that Isaak trusted her enough to let her see. She could count the number of people who knew that Isaak Mikhailovich felt fear on one hand.

Moving like one awkward three-legged creature, they ducked into a narrow building in the line of tight-packed town houses, taking the back courtyard entrance up to the third floor. The stairs were too narrow to walk two abreast, so Isaak followed behind, prepared to catch her if she fell, though she had no intention of doing so. Even from here, she could see the faint haze of warm air from the stove. Her sore bones yearned for the heat.

The sound of raised voices as she opened the door was decidedly less welcome. So much for a calm place to retreat to.

“I won’t tell you again, Ilya,” Irina was saying. “You can think whatever you want, but the moment you start saying it out loud, that’s when you put us all in danger.”

Isaak’s wife stood at the central table in the lone room. Beside her was a tall dark-skinned woman in a soldier’s coat, her face turned away. Even from the back, Marya felt a familiar warmth in her stomach at the sight of Yelena Arsenyevna—tempered with faint unease at what Lena would say when she learned of their escape. Marya knew Lena loved her, but she was also familiar with Lena’s predisposition toward lecturing, and she certainly deserved the traditional “What did I tell you about being careful” speech on this particular occasion. But circumstances had conspired to spare her. Both Irina and Lena had their full attention on the wiry, bearded man in the flat cap who leaned forward with both hands on the table. Marya sighed and sank into one of the remaining chairs. Isaak, it seemed, hadn’t come back a moment too soon.

“Just because you don’t like it doesn’t mean I’m not right,” Ilya said. His voice, as ever, was well oiled with vodka, but Marya didn’t hold that against him. Ilya Zherebetsky had had a hard war, and the two fingers missing from his left hand were a constant reminder of it. Cut off by a senior officer for dereliction of duty, Ilya had told them—attempted desertion before the slaughter at Smolensk that summer, Marya had learned later. “Keep wasting your time on this and you’ll have just enough strength left to flinch as the tsar’s boot crushes you.”

“And you’d rather we what, exactly?” Irina said. From beside her, Marya could see her advancing pregnancy through her unbuttoned overcoat, but God forbid a small concern like growing a human inside her should cause Irina Aaronovna to sit down and let someone else do the fighting. “Storm the Winter Palace and cut their throats one by one?”

“It’s no more than they deserve,” Ilya said. “I don’t expect you to understand, but I’ve seen what they’ve done. Death is too good for them.”

Marya winced. This was not the way to convince Irina of anything. Lena, noticing her at last, moved behind Marya and laid a hand on each of her shoulders. Her fingers kneaded Marya’s tight muscles, a pleasant pain that couldn’t fully distract her from the fight brewing between Irina and Ilya but went some way toward softening its edges.

“You think I haven’t lost anything?” Irina fired back—Marya’s arrival certainly wasn’t enough to dissuade her when she’d made up her mind to argue. “Maybe we have lost less than you, Ilya, if we still have brains enough to know a stupid idea when we hear it—”

“All right,” Isaak said, raising both hands and stepping between his wife and Ilya. All the weariness from the street was gone now. This wasn’t Isaak Mikhailovich the man anymore. This was Isaak the general: determined, inspired, unquestionable. To most of the Koalitsiya, this Isaak was the true one. The legendary commander they’d follow anywhere. It made Marya tired just to watch him, knowing the effort it took to become the leader they wanted.

“You tell her, then,” Ilya said, thrusting one finger toward Irina. “Tell your wife what the Komarovs are capable of, and see if she’s still so set on her damned half measures.”

Isaak’s dark eyes hardened. Even Marya, who knew him better than almost anyone, was afraid of what he might say next. She reached her right hand up to her left shoulder, and Lena took it. “My wife knows what we’re working for,” Isaak said coldly. “She came here from the Pale with me. Believe me, she knows.”

Ilya scowled but changed tack instead of pressing the point. “Oh, I don’t doubt you think you’re doing what’s right, but all this talk of striking? You know them. You can’t think we’ll get what we’re after by asking kindly.”

Ilya’s conciliatory tone was too little, too late. The power had come into Isaak’s posture now, and the fire into his eyes. In this mood, he wasn’t only the leader of the Koalitsiya; he was liberation itself. He had the kind of vision that would live on in songs and legends, that made him impossible to argue with.

“You’re a soldier, Ilya,” Isaak said. “You think a battle’s ever been won by rolling straight into enemy lines with the biggest cannon in your artillery and not caring who you hit on your own side? Just because we’re not making a grand suicidal gesture doesn’t mean I’m afraid. Can you say the same? It’s the frightened dog that bites first.”

Ilya lowered his eyes. Contrite for the moment, though obviously not convinced. Marya, however, was of Isaak’s opinion on that subject: conviction could come later, so long as they had obedience now.

“Come on, man,” Isaak said, and the sternness in his voice melted away, though the strength did not. “Enough of this. I need your help planning a watch over the rally, keep out any unwelcome ears. Put your tactical mind to work on that, and afterward we can talk about the future.”

He drew Ilya aside, into a small alcove of the apartment where they could speak privately. Marya could see Ilya’s pride ratcheting upward with each step, relishing the attention of being consulted personally. Isaak had that effect on people. Even if you disagreed with him, receiving his attention was like being smiled on by the sun in the dead of winter.

“One day,” Irina grumbled, “I’m going to punch that man.”

“If he doesn’t come for you first,” Lena said, shaking her head. She kissed Marya on the cheek, then took the remaining chair at the table, leaning forward to keep hold of Marya’s hand. “Honestly, Irochka, you have to be careful with Ilya and his people.”

“You don’t have to like him, but we do need him,” Marya agreed. “And if you keep antagonizing him, he’ll walk, and take his soldiers with him.”

“Don’t do that,” Lena said, her brow furrowing in what seemed to be both amusement and severity.

“Do what?”

“Try to pretend you’re the reasonable one here. What happened? You and Isaak look like you just fought Bonaparte.”

“Complications,” Marya said wearily. “Don’t go near Kronverkskiy Prospekt for a week or two, to be safe.”

Irina swore and closed her eyes. “Did they see you?”

“I don’t think so,” Marya said. “They knew someone was there, but I don’t think they’d recognize us by face. It could have been worse.”

“Could have been better, too,” Irina muttered.

“Take that up with your husband,” Marya said. “Printing them up was his idea.”

“Oh, I intend to. Once he’s finished dealing with this disaster, I’ll shout at him about the next one.”

Marya laughed. No matter how dire matters got, Isaak and Irina would always be like this, each as annoyed with the other as they were in love with them. Lena had taught her how to understand that sort of love. Rolled eyes and an embrace could mean the same thing, from the right person. Exhaustion washed through Marya, kept at bay until now by adrenaline, and she allowed her eyes to droop. Lena drifted toward the window, where a basin of water rested on the ledge next to the Tverskys’ silver sabbath candlesticks and three of Isaak’s prized, battered books. Returning with the basin and a handkerchief, she nodded, and without being asked Marya placed her shredded palm in Lena’s lap. Lena swirled the handkerchief in the basin, then washed away the blood and dirt with an artist’s care. The water in the basin took on a pinkish tinge, reminding Marya oddly of poppies. Love could look like this, too. A bloodied handkerchief and a soft touch.

“It’s not as bad as it looks,” Marya said, though the chair made her bruised hip ache.

“It had better not be.”

“We got what we went for. Other people would call that a success, you know.”

Lena scoffed. “I’ll congratulate you when you come home to me in one piece, which is all I’ve ever asked you to do.”