5,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 2,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WriteLife Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Madelyn Kubin was a 70-year-old Kansas farm wife. She appeared to be fragile because of her thinning white hair, macular degeneration, osteoporosis, congestive heart failure, and severe hearing loss. But when her husband Quentin suffered a debilitating stroke, she was forced to summon all of her physical, emotional, and spiritual strengths in order to care for him at home. Madelyn managed her isolation, loneliness, and stress by going to her computer, disengaging her emotional monitor, and writing letters to her daughter Elaine.

Madelyn’s story of faith, courage, and love is told through her unflinchingly honest and surprisingly funny letters written in real time over the course of six-and-a-half years. Although she prayed every day that she would be a willing channel for God’s love and compassion, there were plenty of days she felt like telling God to go find himself another servant.

Madelyn wrote unabashedly about her anger, guilt, depression, and grief. When Quentin displayed dementia-related inappropriate sexual behavior, Madelyn eventually learned how to handle it with grace and humor. She was an example of how it is possible, even in the very worst end-of-life situations, to experience mental and spiritual growth.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

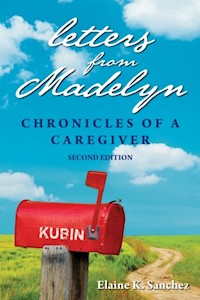

Letters from Madelyn, Chronicles of a Caregiver

© 2016 Elaine K. Sanchez. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, digital, photocopying, or recording, except for the inclusion in a review, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published in the United States by WriteLife Publishing

(an imprint of Boutique of Quality Books Publishing Company)

www.writelife.com

978-1-60808-166-0 (p)

978-1-60808-167-7 (e)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016934822

Book and cover design by Robin Krauss www.lindendesign.com

To my mother—who believed with every fiber of her being

that she had the power to choose her attitude

toward any person, thing, or event.

Madelyn’s Family in 1993

Husband

Quentin Kubin

Married September 6, 1942

Children

Larry, born in 1946—Married to Teri: Daughters Christy and Candi

Larry farms with Quentin and lives in the house next door.

Greg, born in 1948—Married to Deb: Children Mardee and John

Moscow, Kansas

Gene, born in 1949—Married to Gloria: Children Jennifer and Danny

Kansas City, Kansas

Elaine, born in 1951—Divorced: Children Eric, Robert, and Annie

Colorado Springs, Colorado

Madelyn’s Sister

Jean, married to Frank

Hudson, Florida

Sister-in-law

Marge, widow of Quentin’s brother Dale

McPherson, Kansas

Prologue

On October 30, 1993, I picked up the ringing phone. It was my mother. She said, “Your father’s had a stroke.”

Knowing this was his worst fear, I asked, “How bad is it?”

She said, “It’s really bad. The right side of his face is all lopsided and droopy. He’s completely lost the use of his right hand. He’s having a terrible time walking, and when he talks, I can’t understand a word he says.”

“What’s the prognosis?”

“It’s not good. The doctor said he also has prostate cancer, and they think maybe the cancer’s already spread to his brain.”

“Oh, Mom,” I said, sinking into the nearest chair. “I’m so sorry. What can I do?”

Her voice broke. “Could you please come home?”

At that time I was a single mom with three teenaged children. My son Eric was a high school senior, and that Friday night was the final football game of the season. It was Mom’s Night. All of the mothers were to go out onto the field at the beginning of the game, and our sons were to hand each of us a single red rose.

It was also the last time Eric and his brother Robert, who was a junior, would ever play for the same team on the same night on the same field. In addition, we were planning to celebrate my daughter Annie’s fifteenth birthday.

As I thought about how badly I wanted to be with my children that weekend, I heard myself saying, “Of course. I’ll pack tonight and get on the road first thing tomorrow.”

I left Colorado Springs early the next morning. As I drove the 450 miles across the barren plains of eastern Colorado and western Kansas, I had plenty of time to think. Even so, I simply could not grasp the idea that my dad, who appeared to be as healthy and robust as any seventy-five-year-old man on the planet, could be brought down by a stroke.

He was still farming. Men in our family didn’t get sick or die in their seventies. On my Uncle John’s ninety-third birthday, he bought a new suit. He told the clerk he was afraid he’d wear out the pants before the jacket, so he ordered two pair of identical trousers. The clerk thought that was wildly optimistic. The people in our family thought it just made good sense. I expected Dad to have another twenty years, at least.

Had it been Dad who called and said something had happened to my mother, I would have been devastated, but I wouldn’t have been surprised. Although she was only seventy, her poor body was nearly worn out. She had a little cottony puff of white hair that barely concealed her scalp. She was losing her vision due to macular degeneration. Her back was hunched from osteoporosis. She had a scar that started at her throat and extended to her breastbone as a result of open heart surgery, from which she had not fully recovered. She didn’t sleep at night because of her restless leg syndrome, but the thing that was frustrating her beyond all belief was the severe hearing loss that had been brought on as a result of the medication she was taking for her heart.

And now she was going to become Dad’s full-time caregiver. It just wasn’t right!

But then a lot of things weren’t right in my life, either. I was forty-two and divorced. My ex-husband hadn’t held a steady job for a long time, and he didn’t pay child support. I was still reeling from the loss of my job as general sales manager for the NBC television affiliate in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Six weeks earlier, my boss had walked into my office and closed the door. He sat down across from me and said, “You’ve got a problem.”

I said, “I do?”

He said, “I don’t like you anymore. You push yourself too hard. You push your employees too hard, and you scare people. Get your purse and get out.”

I was stunned. I was just four days away from closing on the sale of my 4,500 square foot home on a golf course and moving into a new, smaller town home, which I was scheduled to close on the next day. I was also driving a company car. So in that brief and brutal encounter, I not only lost my job, I also lost my home and my car.

My confidence was deeply shaken. My future was uncertain. My children—who were also unsettled, upset, and confused—were pushing every limit, and now my dad was dying. Naively, I thought things couldn’t get any worse.

After eight hours on the road, I finally reached McPherson, a town of about 14,000 people in central Kansas. I drove straight to the hospital. I was told I’d find Dad in Rehab. When I entered the room, I was stunned to realize that the fragile old man being supported by the physical therapist on a slow-moving treadmill was my dad. He was wearing tennis shoes and forest-green sweats bunched up and twisted at the waist. I’d never seen him in clothes like that. When he saw me, he tried to smile. His mouth was lopsided, and his brown eyes, normally twinkling with mischief and laughter, were abnormally round and wide. He looked scared and helpless—like an animal caught in a trap.

I looked at my mother and wondered how she was going to manage what lay ahead. My parents lived on a farm six miles northwest of McPherson. Their primary asset was 320 acres of land, half of which was homesteaded farm ground that had been in Dad’s family since the late 1800s. There was no long-term-care insurance and only a few thousand dollars in savings.

My dad loved my mother more than anything on earth, except for the land. If she sold it and put him into long-term care, she would not only be violating a sacred trust, she would also be putting my brother Larry, who farmed with Dad, out of business. If Dad lived for a long time, it could take all of the money to pay for his care, and it was possible that she could end up being destitute.

I don’t remember how long I stayed in McPherson. It couldn’t have been more than three or four days. I did whatever I could to help Mom and encourage Dad, and then I had to go back to Colorado to rebuild my own shattered life. In the first few weeks after I lost my job, I’d been forced to make a lot of quick decisions, including finding a house to rent, buying a car, landing a job, and taking the next step with a man in our relatively new relationship. Some of my decisions were good—a lot were not.

I was operating in a fog of confusion and self-doubt. I didn’t understand why my life had unraveled so completely, and I wasn’t sure I’d ever be able to piece it back together; but at least I still had choices.

Mom did not. Dad’s stroke ended her freedom. There were days when she could escape for a few hours to run errands or attend a meeting, but for the most part she was held captive for the next six and a half years.

She developed a multitude of strategies that helped her cope with her isolation and emotional stress. She believed in a loving and benevolent God. She frequently visited the library and checked out stacks of books that provided her with information, inspiration, and a temporary escape from her duties as a caregiver. And she wrote letters to me.

She would often go to her wildly cluttered desk, disengage her emotional monitor, and let her flingers fly across the keyboard of her word processor as she described everything she was experiencing and exactly how she felt about it.

A typical letter would be five to ten pages in length, typed, single-spaced, and printed on both sides of the page. To me, each one was like an episode of M*A*S*H. There was always something that made me laugh, something that made me cry, and something that proved how it is possible to find peace and joy in the midst of crisis and tragedy.

In 2004, I was asked to speak at our church on Mother’s Day about mother-daughter relationships. I decided the best way to describe Mom was in her own words, so I went to the garage and took down a cardboard moving box my husband had labeled, “Letters from Madelyn.” I read an excerpt from one letter and told a few stories. Afterward, people came up to me and exclaimed, “You have to write a book!”

I started on it the next day.

In the beginning, I had some reservations about sharing such a personal story, but when I came across the following paragraph, I knew Mom had given me her permission:

She wrote, “I wish I had been keeping a journal all these years. It would be interesting now to see the stages I have gone through. It has taken many years to get to this place of detached peace and acceptance. Thank God for this place! I also think my experiences might be helpful to other people who are in a similar situation.”

By publishing these letters, I hope to honor my mother’s memory and fulfill her wish of helping others who find themselves struggling to cope with the emotional stress of caring for a loved one who is a stroke survivor or suffering with any type of long-term progressive and degenerative disease.

Contents

Chapter 1: 1994

Chapter 2: 1995

Chapter 3: 1996

Chapter 4: 1997

Chapter 5: 1998

Chapter 6: 1999

Epilogue

Addendum

Acknowledgments

January 6, 1994

Dear Elaine,

You will be glad to know that my chest pains have stopped. They got pretty bad right after Quentin had the stroke. I was beginning to wonder if I should go to the doctor, but I didn’t want Quentin to know how much trouble I was having because he worries about the extra load I’m carrying.

One night I was reading an old Daily Word1 and I found the affirmation, “God is healing all now. Thank you, God.” That really appealed to me. I started repeating it to myself over and over and my pains stopped.

Day before yesterday I couldn’t stop crying. The last two months just came to a head. I’d had some chest pains during the day and a few in the night, but they have gone away again. It is such a relief to be free from them. I do indeed “Thank God.”

It was a year ago today that we left for Florida. Kansas was covered with ice that night. It is supposed to get real cold here tonight—and I believe the weather forecasters are right—at 4:00 p.m. it was 25 degrees. We haven’t been out of the house all day.

Quentin is still feeling sad about his brother. He said he didn’t want to go over to the house right after Dale died because he thought I would be too upset. I finally said that I just had to go. We got over to Marge’s house and Quentin cried real hard. He was real embarrassed that he cried; but it was all right, it endeared him to Marge. He was afraid to go to the funeral. He got through it okay, but he looked pretty tough. It was a beautiful service. There were lots of flowers, and there were even people in the balcony.

The house you rented sounds dreadful, and it must be hard for the kids since they’ve always lived in a beautiful home, but I’m sure you won’t have to stay there too long. I’m real proud of you for what you are doing. So many people blame everyone else for their troubles and problems, and they never go to the effort to look within to see what needs to be changed. You will come out of this stronger, smarter, and more compassionate rather than bitter and defeated.

The new job sounds interesting. Have to admit I don’t know much about the corporate hospitality business. I can’t imagine how you’ll persuade companies to spend so much money on taking employees or clients to baseball games, but I never understood how you got people to spend so much on television advertising either. If the Rockies turn out to be as popular as the Broncos, you should do real well. And even though the commute to Denver makes your days awfully long, it’s good that you’re taking the time to think about the things you need to do to change your life.

I’ve been thinking about your kids a lot and I think the dilemma is very predictable. They don’t like having to share you with someone else, and I wouldn’t be surprised if they don’t resent someone else taking “Daddy’s” place. It must be very hard for them to get used to John living in your house. You are raising kids in a very difficult time and they are a very difficult age. I don’t envy you, and I pray for all of you every night.

We are looking forward to seeing you again, but don’t come until your situation is under control. Quentin is still having so much trouble breathing, and the flu or a virus would devastate him.

He still gets nervous very easy, but is doing better. He doesn’t like to have me talk about his sickness, or anyone else’s for that matter. That’s the reason I’m writing. So when you do come home we can spend our time on much more interesting subjects. I get real lonesome to see people and to have a good conversation.

Love,

Mom

February 6, 1994

Dear Elaine,

I feel so “blah” today. I have written to my sister Jean and that’s just about my total accomplishment, except for making the beds, fixing three meals, and washing a load of clothes. I did help Quentin with his shower this morning. Yesterday I managed to get the magazine racks and refrigerator cleaned and felt good about the day.

I went to a home in McPherson that had a sign in front saying Kirby Vacuum Cleaner supplies were available. I was desperate for dirt bags, so we went there. I have never in my life seen such a mess. I went out to the car and told your dad that I had seen someone who was messier than me. It didn’t comfort me—it scared me. Decided I had better get everything straightened out and develop some habits that will be helpful as I get older. Can’t believe I need to clean my closet again. I did it only six years ago!

I will sure be glad when it warms up so we can get out and walk. Quentin isn’t walking nearly as well as he did for a while. He has had some trouble with his rear end, so he doesn’t feel like riding the bicycle. He was all broken out and has had trouble sleeping because of his itching skin. We think the chlorine in the swimming pool caused the irritation. We haven’t been to the Y since the first of December, but his skin is just about healed now.

It’s harder all the time for him to get out of bed. Thank goodness Greg came home and installed the ceiling hoist. I honestly don’t know what we would do if we didn’t have it. Last week I happened to be in the bedroom several times when Quentin was struggling, and I helped him up with the hoist. Then one night, I had severe chest pains. It used to never scare me, but it’s hard to not get real concerned now, as I am needed very much. I sat in a chair and worked at relaxing. I have a little ball with knobs on it that is great for using reflexology on hands. I had read that rubbing the end of the little finger on the left hand has stopped lots of chest pains, so I did that, and I put on a nitro patch. The pains didn’t last too long, but I did learn that I just can’t be pulling him up all the time.

When he is tired at night, he breathes as if he’s run up about three flights of stairs. I asked one time if the trouble came from his head or his chest. He said it was his chest. I asked where it hurt, and he said it went deep. He asked me one time to pray that he would die from heart trouble. I can’t bring myself to do that, but I hope when the time comes for him to make his transition that it will be fast. I’m so glad he’s not in pain. He has some discomfort at times, but he is not in terrible pain.

Sometimes I feel like I’m toilet training a little child—I’m always either asking if he needs to use the bathroom or I’m telling him to do so. Sometimes when he goes to lie down for a nap during the daytime, he won’t use the bathroom. In just a little bit he’ll need to go, but he can’t get up in time. So now every time he goes to lie down, I tell him to go to the bathroom first. When he says he doesn’t need to, I tell him to go anyhow. When we go to town, we take the urinal along, as he quite often has to go and there isn’t a bathroom. He has a lot better control now that I’ve been questioning him about every two hours. I have to be careful that I don’t show irritation with him.

The one place where I don’t give in to him is when I want to sit up and read at night. He never wanted me to do that when he was well. Now he says he can’t sleep if the light is on, and the noise of the turning pages bothers him. He never has any trouble sleeping in the daytime. The dishwasher can be going, the TV can be on, and the telephone can be ringing, and he can sleep without any problem. I told him last night to not worry if he couldn’t sleep while I was reading, because he wouldn’t have any trouble when it’s daytime and I’m working. I need some time for myself, and if he can’t sleep, he will just have to stay awake.

It is not a fun-filled life for either one of us. Fortunately, there are still a lot of things I can do. He can only read, sleep, or watch TV.

I enjoyed talking to Eric the other night. He said his dad hopes to move them out of Grandma Jane’s basement and into their own apartment soon. Even though she loves them all, I can’t imagine she’s enjoying having Craig and three kids living with her. I know I wouldn’t want them!

I think Eric can do very well as a waiter if he doesn’t get too unhappy with his customers. If he makes enough money in tips, he’ll probably learn to be patient. I know a young woman in Chicago who is working as a waitress. She got a degree in sociology but couldn’t get a job in that field. She’s doing real well financially. Her mother said she likes to wait on Jews and homosexuals, as they tip very generously.

I’m enclosing the letter I sent to Eric in his birthday card. I hope he’ll read it and think about it.

Lots of Love,

Mom

January 30, 1994

Dear Eric,

As I think back eighteen years to the day you were born, the tears are streaming down my face. I have told you before how happy and proud everyone was. I hope we can all feel that way again soon. I hope you will read this letter all the way through. If you can’t now, please save it and read it another time.

As I told you yesterday, I am so sorry about what has happened. It is up to you now to shape your life the way you want it to be. You are old enough to be considered a man, so you are old enough to make your decisions as to how you are going to live. I had a friend who told her kids, “Don’t blame me for your life. I’ve done the best I know how. If you are smart enough to know what is wrong, you are smart enough to correct it.”

Every day of our lives we make decisions that have an influence on the following days. Some decisions are not momentous ones—others are. The decisions to drink, do drugs, get involved in crime, etc., frequently have devastating effects that are painful to correct.

I keep thinking about where you are going to live since you can’t abide by your mother’s rules. I doubt very much that your friend’s parents would be thrilled to have another disagreeable, slovenly teenager around. If you stay with a friend, you had better hang up your coat, keep your room clean, get to meals on time, stay out of trouble, be agreeable, and pay some rent.

As I told you yesterday, I am trying to think of your good qualities and envision you using them. I was so proud of you the summer you worked at Village Inn and you took pride in being the best dishwasher that restaurant ever had. It is admirable to be a good dishwasher at sixteen, but it loses a lot when a person is an adult and can’t do anything else. You will find that your chances for a good job are very slim without college.

Until recently, you have been kind, loving, and supportive of your mother, which was another admirable trait. Whatever you do, don’t base your actions on trying to hurt her, because it won’t work. She has been hurt about as much as she can be, and anything you do to hurt her further will hurt you even worse.

You and your mother are very angry with each other now, and I am hoping that in time you will remember all the loving things she has done for you and how she was always there loving and supporting you.

I hope you are still reading and that you will keep in touch with me. Remember, I have confidence that you have the ability to succeed. You must graduate from high school, and you must decide on the future. It is all in your hands. You can watch interviews on TV with homeless people and decide if that is the way you want to live. You have always lived in a beautiful home and had good clothes. No one else is responsible for seeing that you continue that way except you.

We have been praying for all of you every night that you will accept God’s guidance and love in your lives. We will continue. However, God will not come down and hit you on the head with a good job, life, or opportunity. He can only do for you what he can do through you.

You have the mind and the ability to do something challenging and worthwhile—now do it!

God Bless and Love,

Grandma

May 15, 1994

Dear Elaine,

Teri mentioned last week that she thought Quentin should be in an intensive rehabilitation program. I called the doctor, and he said we should call the rehab center at Wesley Hospital in Wichita. I got ahold of some idiot on the phone, and she said, “You would drive all the way down here?”

She went on to say that she doubted if they could get him in and recommended I contact the rehab hospital on the west side of town. I kept calling different places, and it seemed to me that everyone I talked to was so dumb and unknowledgeable that they wouldn’t be able to help him anyway.

I finally got in touch with a delightful woman who is going to come to the house on Monday to evaluate him. Her company offers speech, physical, and occupational therapy. We are looking forward to having her come and hearing what she has to say. I spent a fortune on the telephone (during prime time) trying to find something. I talked to a woman who used to go to our church who is now a speech therapist in Hutchinson. She wasn’t very encouraging, as she said there was a time limit for Medicare following a stroke. She said it could be terribly expensive now.

Still, I’m going to pursue it. Sometimes I can’t understand a word he says. He has to repeat himself about three times for me to catch enough to figure out what he is saying. He blames it on my hearing, but it is still demoralizing for him, and I feel bad about it. I miss not being able to talk to him, and I want my buddy back.

We had a tragic and shocking event in town last week. Delbert and Mildred Peterson were found dead. He was in his pajamas in the living room, and she was in the garage in a car. The pickup and car had both been running, and apparently the door between the garage and the house was open, because there was carbon monoxide in the house. The dog was dead, too.

I think it must have been twenty years ago that Delbert told Quentin if anything happened to him (Quentin) that I’d be able to handle it. He went on to say that his wife wasn’t that strong. In the last four years she’s had two strokes, two mastectomies, both knees replaced, etc., etc. She had an appointment to go to an oncologist on Friday. No one knows exactly what happened or why, but there are about as many stories as there are people to tell them.

I can understand their desperation, but I don’t think I could ever accept suicide as a solution.

Have to run to get this in the mail.

Love,

Mom

May 18, 1994

Dear Elaine,

I’m so happy you got moved into your new house. It sounds wonderful. I know it was hard on you living in the “ghetto” rental house. Women’s rights have come a long way. It wasn’t long ago that a single woman would have had a hard time buying her own home.

I looked at the Rockies schedule this evening. I see that they have a lot of home games for the next two weeks, so it looks as if it will be hard to call you. I hope all your parties go well. I can’t imagine that GM would spend $10,000 for one party at a baseball game. I’m happy for you, but I bet they could sell their cars for a lot less if they weren’t quite so free with their money.

I went in for blood tests earlier in the week. The LPN stuck me three times before she gave up and called for help. When the nurse came in, I told her I hoped the doctor would get busy enough that the LPN would get practiced in taking blood.

The doctor called today to say everything was fine except the triglycerides. It should be under 200, and mine was 480. We’ve been eating eggs every morning and have had a lot of toast with Parmesan cheese. I told Quentin I thought we might be eating too many eggs.

He said, “Don’t take my eggs away. What am I going to eat?”

I was standing by a window looking out at the grass, and I told him I was thinking about putting him out to eat grass. Guess I will have to go with him.

Your dad seems to be doing better. He played golf with Gene on both Saturday and Sunday. When he got tired, he just rode along in the cart. He doesn’t hit the ball a long distance, but it seems to be going pretty straight.

He’s been doing a little bit of tractor work. He planted corn for a couple hours last Friday—worked in the field a couple hours yesterday morning, and then mowed the lawn for four hours. He is still having trouble with his breathing and the phlegm in his throat, but it is better. He has not made the divan out into a bed for over a week now. We both alternate between the La-Z-Boys, the couch, and the bed, but he is getting more sleep than he did for a while.

I sure felt good after seeing your kids the other day. They have a nice apartment with their dad. It’s a duplex and is quite new. It was rather sparsely furnished. The furniture wasn’t new, but it wasn’t disreputable either. The boys said I couldn’t go downstairs—that was their area and it was a terrible mess. Eric is looking forward to going to college in the fall. They all seemed to be in good shape. I told Eric that you were coming for his graduation and said I hoped you could get together. He said, “We’ll see.” He had tears in his eyes, so I thought that was encouraging.

Your relationship with your kids right now is not as unusual as one might think. I have heard of several situations of estrangement that did eventually get straightened out. The training the kids have had from you is a real asset to them now. They do know how to take care of themselves—cook, clean, do laundry, etc.

I think I told you about getting up one morning and having this thought come through: “They are nourished from the roots.” I don’t know for sure what that means, but I felt very peaceful about it. I’m sure their dad keeps feeding them a lot of his anger, which makes it difficult for them.

I’m sorry John is giving you a hard time about coming back for Eric’s graduation. I can see why he doesn’t think much of your kids right now, but I do agree with you that this is important. Graduation is something that only happens once. I admire you for sticking to your guns. Even if they won’t admit it right now, your kids love you and they need to know that you still love them. Besides, I’m sure John’s daughter will enjoy having some one-on-one time with him. I wonder if she’ll want to move to the US too. England might look old and dreary in comparison to Colorado.

Everything here is so lush right now. Quentin and Teri mowed the yard Tuesday and it’s beautiful. I am enjoying the tree you gave me. I planted my flowers from seed this year. It’s cheaper, and there is a fascination to watching the plants come up and grow. I have ten tomatoes, two peppers, and one zucchini plant. Have to transplant some more flowers tonight.

Lots of Love,

Mom

June 23, 1994

Dear Elaine,

Quentin and I were taking a nap the other day and he heard Gene yell, “FIRE!” on our business band radio. The temperature was close to 100, but thankfully the wind wasn’t blowing. The fire started inside one of the combines. Gene saw it and yelled on the radio to Candi that she had a fire. She grabbed her water jug and the fire extinguisher and jumped off the platform, but the stubble had already caught fire. Larry came on the scene at that time, and he called to everyone to get their equipment out of the field.

When Quentin finally got his pants on, he stood up and said, “I can’t take this.”

My heart started pounding real hard, and I said, “I can’t take it either, but we can’t stay home!”

We decided to take the van in case we needed to haul people to the hospital. On the way over to the fire, Quentin told me to take him by the field where he’d been working earlier so he could get the tractor and plow.

I called 911 and gave the fire department directions to the field, but as Quentin and I were driving, I commented they wouldn’t have any trouble finding it, as there was a big, long line of smoke. There were two real dark spots, and Quentin thought it looked like equipment burning.

When I got to the field, Teri’s folks were already there. They’d seen the smoke on their way home from town. I was relieved when I found out everyone was all right. I told them that Quentin was on his way over with a tractor.

We all looked down the road and here he was coming. It was a very dramatic, memorable moment. There wasn’t another vehicle in sight—just this one John Deere with Quentin driving it. There was absolute silence for a few seconds, and then Teri and her mother started saying that Quentin shouldn’t be out in the smoke, which was quite intense.

Larry went buzzing out of the field in his pickup, met Quentin at the corner, and they traded. As I mentioned earlier, it was hotter than hell, and all the kids were about prostrate. All the water had been used to stop the fire.

Teri’s mother, sister, and I went to the house and grabbed everything we thought might be helpful. I took a sack of ice, several bottles of drinking water, two big pitchers of orange juice, a carton of Pepsi, three wet towels, and lots of cups. We had plenty for everyone—even the firemen. An ambulance came out from town.

When the fire was out and everyone had been refreshed, Larry commented that he needed to get his combine out of the field. Quentin volunteered to go get it. Larry let him open up the adjoining field—I guess to see if the combine was working all right. When Quentin got off, he said he knew he couldn’t drive a combine anymore, but he sure had enjoyed that. He hadn’t been so happy in ages.

Quentin went back to the field to continue plowing. He came in at 6:30 for supper. When he finished, he stood up, grabbed his hat, and headed to the door. I said, “You aren’t going back to the field, are you?”

He said there was just a little bit left, and he wanted to finish it. At eight o’clock, I called him on the radio and asked if he was going to work all night (in a not-too-nice tone of voice). He assured me that he was almost through. He finally came dragging in at 9:30.

I’m not at all proud of myself, but I met him at the back door hollering, “If you have another stroke it had better by-God kill you!”

I went flouncing off to the living room. He followed me in saying he was sorry, and he just hadn’t realized how late it was. I was still mad, and I informed him that you didn’t have to be particularly smart to know when the sun goes down, dark settles in, and the moon starts to shine, that it’s time to quit. He had been out since 7:30 in the morning, with just a little over an hour off at noon, and time enough to grab a quick sandwich in the evening.

I’m still convinced the reason he had the stroke last summer was because he’d been working too hard. When he said he was retiring last year, he promised he wouldn’t work on Sundays or after supper anymore, but he still came in every night between 9:00 and 11:00 p.m.

I feel I was entitled to be scared and mad, but he did look so good and happy that I’m sorry I jumped on him the way I did. He hasn’t had much energy since. Who knows whether it’s because he worked too long and got too tired, or because he was reminded so forcibly that he can’t work and live the way he has for the last forty-eight years.

Love,

Mom

August 14, 1994

Dear Elaine,

Sleeping in one bed has become almost impossible for us. We’ve spent most of our nights in our La-Z-Boys. It’s easier for Quentin to breathe with his head elevated, and it seems to ease my back and chest pains.

I decided to buy two twin-sized hospital-type beds that we can scoot together. We can elevate the heads, and they bend around the knees, too. This will eliminate the problem of lying flat, and we can still be together. I sincerely hope we like the new beds as much as we think we are going to. I know we would both feel much better if we could go to bed and sleep all night.

I think we are going to get cable tomorrow. I don’t need TV because I can’t hear, and I really prefer to read, but reading is hard for Quentin now. He just can’t concentrate, but he can enjoy TV. Won’t it be wonderful that we’ll be able to watch the O. J. Simpson trial from beginning to end—all day!! I can hardly wait!

There are so many things we can’t do or don’t want to do, that we’ve decided we’d better make life as pleasant and comfortable as we can. We are so grateful for the trips we’ve taken and the fun we’ve had. We might never be able to do a lot of those things again, but there’s no point in sitting around crying over what can’t be. We need to concentrate on what is possible and what we can enjoy. We don’t enjoy eating out much anymore. It almost makes me ill when the bill comes.