Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

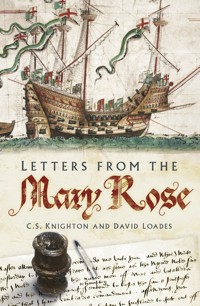

'The authors are to be congratulated on a book which merits usage in the national curriculum.' - International Journal of Nautical Archaeology The raising of the Tudor warship Mary Rose in 1982 has made her one of the most famous ships in history, though there is a good deal more to her story than its terminal disaster. She served successfully in the Royal Navy for more than thirty years before sinking, for reasons still uncertain, during a battle off Portsmouth in 1545. There have been many books published about Mary Rose but this is the only one written largely by those who sailed with her. It is based around original documents, including all the known despatches written aboard Mary Rose by the commanding admirals. Extracts from accounts and other papers illustrate the building, equipping and provisioning of the ship. Although this is primarily a view from the quarter-deck, there are occasional glimpses of life below. The collection concludes with reports of the sinking, and of the first attempts to salvage the ship and her ordnance. The documents are presented in modern spelling and are set in context through linking narratives. Technical terms are explained, and the principal characters introduced. The texts are supplemented by contemporary images, and by photographs of the preserved ship and recovered objects. A new range of illustrations has been added to this edition, published forty years on from the raising of the hull.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 370

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

But one day of all other, the whole navy of the Englishmen made out, and purposed to set on the Frenchmen; but in their setting forward, a goodly ship of England, called the Mary Rose, was by too much folly, drowned in the midst of the haven, for she was laden with much ordnance, and the ports left open, which were very low, and the great ordnance unbreached, so that when the ship should turn, the water entered, and suddenly she sank.

Edward Hall, Chronicle, 1548

Cover Illustrations: The Mary Rose in the Anthony Roll (The Master and Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge); Pen and inkpot from the Mary Rose (The Mary Rose Trust); Letter from Lord Admiral Howard to Thomas Wolsey, 14 May 1513. (Public Record Office)

First published 2002

This new paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© C.S. Knighton and David Loades, 2002, 2022

Published in association with The Mary Rose Trust

The rights of C.S. Knighton and David Loades to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9074 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Preface

Preface to the Second Edition

List of Illustrations

List of Colour Plates

Note on Measurements

Introduction

1 The Building and Equipping of the Ship (1510–14)

2 The War with France to the Death of Sir Edward Howard (April 1512–April 1513)

3 The War with France after Sir Edward Howard’s Death (April 1513–May 1514)

4 Laying Up and Out of Service (1514–22)

5 The War of 1522–25

6 Laid Up and (Mainly) Out of Service (1525–42)

7 The War of 1543–46, and the Loss of the Mary Rose

8 Salvage Attempts (1546–49)

9 The Aftermath

Postscript: The Resurrection of the Mary Rose

List of Abbreviations

Appendix I: Key to Documents

Appendix II: List of Persons

Appendix III: Glossary

Appendix IV: Map of Fleet Dispositions, 19 July 1545

Notes on the Authors

Bold figures in the Introduction and the commentaries in each chapter refer to the numbered documents that form the second part of each chapter.

PREFACE

Henry VIII’s warship the Mary Rose had served for over thirty years when she sank before the King’s eyes in 1545. This book presents a selection from the many documents which log the ship’s career; chiefly, we print all the surviving dispatches written aboard during her first two periods of active service. The texts have been set within a continuing narrative which explains specific circumstances and fills in gaps for which there is no documentary coverage. The written record is accompanied by photographs of material from the wreck recovered and conserved by the Mary Rose Trust.

The project would have been impossible without the collaboration of Alexzandra Hildred and Christopher Dobbs. We are greatly indebted to them for their advice and assistance and to Andrew Elkerton and the Mary Rose Trust for providing many of the illustrations. The map has very kindly been provided by Dominic Fontana of Portsmouth University. We are very grateful to Jane Crompton and Christopher Feeney, and their colleagues at Sutton Publishing, for accepting the book and bringing it into being. For additional help we must thank Simon Adams, Lisa Barber, Aude Fitzsimons, Ian Friel and Judith Loades.

Portraits in the Royal Collection are reproduced by gracious permission of Her Majesty The Queen. The portrait of Lord Paget at Plas Newydd is reproduced by kind permission of the Most Honourable the Marquess of Anglesey. The portrait of the Duke and Duchess of Suffolk at Woburn Abbey is reproduced by kind permission of the Marquess of Tavistock and the Bedford Settled Estates. Lord Lisle’s dispatch of 1545 is printed by kind permission of the Most Honourable the Marquess of Salisbury. We are grateful to Dr H.G. Wayment for supplying a print of his photograph of the window in Fairford church which he has identified as a portrait of Wolsey. Dr M.H. Rule, CBE, has kindly allowed us to use her photograph of the raising of the hull of the Mary Rose. For help with the documents and illustrations we are also grateful to Messrs P. Barber, S. Roper and N. Spencer (British Library), Miss S. Burdett (National Trust), Mr R. Harcourt-Williams (Hatfield House), Messrs P. Johnson and A.H. Lawes (Public Record Office), Miss L. Nicol (Cambridge University Press), Dr E. Springer (Österreichisches Staastsarchiv), Miss S. Smith (Royal Collection) and Miss L. Wellicome (Woburn Abbey).

The documentary texts and editorial apparatus have been the responsibility of Dr Knighton; the commentary was written by Professor Loades.

C.S.K.

D.M.L.

London, August 2001

PREFACE TO THESECOND EDITION

Professor Loades died before this paperback edition was in prospect. His introduction and commentaries remain as originally published; I have merely appended a brief note of subsequent developments. The opportunity has, however, been taken to correct some errors. It is particularly regretted that a misprint in one text was transmitted to Dr Robert Hardy and reproduced in his and M. Strickland’s The Great Warbow (2005) (p. 4 there). Needless to say the responsibility for remaining errors is now vested in the surviving author. The central section of colour photographs has been substantially revised, showing some items recovered since 2002. Many thanks are again owed to Alexzandra Hildred and her colleagues at the Mary Rose Trust for producing these striking new images. With the collaboration of Dr Dominic Fontana, the papers printed here were supplemented by ‘More Documents for the last campaign of the Mary Rose’, in The Naval Miscellany, Volume VIII, ed. B. Vale (Navy Records Society, vol. XLXIV, pp. 49–84).

C.S.K.

Clifton, May 2022

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. Leather shoes

2. Tableware

3. A precise replica of the brick galley found on board

4. An inkwell made of horn

5. Tudor rose emblem

6. Navigational equipment

7. Bone carving of an angel

8. Items associated with a gunner

9. Thomas Wolsey, as depicted in a window at Fairford church

10. Materials indicating evidence of literacy

11. Two pots

12. Henry VIII’s arms

13. Personal items

15. Plymouth harbour

16. Letter from Lord Admiral Howard to Thomas Wolsey, 14 May 1513

17. Reconstruction of the firing of a longbow

18. One of the complete yew longbows recovered

19. Barber surgeon’s cap

20. Barber surgeon’s equipment

21. A wrist guard (bracer) worn by an archer

22. Chest recovered from the barber surgeon’s cabin

23. A compass

24. Log reel

26. Barrel end

27. Pouring beer into the reconstructed galley

28. The reconstructed galley

29. Ordnance equipment

30. Dartmouth harbour

31. A ceramic cooking pot

32. An iron nail

33. Carpenter’s equipment

34. Tableware

35. A bastard culverin

36. A corroded example of a base

37. A bronze demi-cannon

38. Hailshot piece

39. Arrows with spacer

40. A detail from the Cowdray engraving

41. The Duke and Duchess of Suffolk

42. Sir William Paget

43. A whetstone and holders

44. Portsmouth fortifications, 1545

45. A seaman’s chest

46. Ceramic pots

48. Linstocks

49. Items of sewing equipment

50. The recovery of the hull

51. The Mary Rose preserved

52. The tomb of an unknown sailor from the Mary Rose, in Portsmouth Cathedral

53. Corroded base of gun

54. Demi-culverin on carriage

55. Hailshot piece

56. Port-piece

LIST OF COLOUR PLATES

These are in an unpaginated section between pp. 156 and 157.

Plate 1 The Mary Rose returning to Portsmouth 1982

The recovered hull being sprayed with chilled water

Plate 2 Chest, lantern, tankards and other recovered objects

Pewter dinner service bearing the initials of the Captain

Plate 3 Domestic and personal objects of wood

Stern to bow view of the museum galleries

Plates 4–5Mary Rose in the Anthony Roll

Plate 6 The ship’s watch bell

The ship’s emblem

Plate 7 Gold angels

Plate 8 Views of the museum galleries

NOTE ON MEASUREMENTS

In the transcribed documents Roman numerals have been rendered as Arabic, and the conventional abbreviations applied as standard; otherwise measures are given as nearly as possible to the format of the original MSS.

Currency

The pound sterling (£) of 20 shillings, the shilling (s) of 12 pence (d). The mark (13s 4d) was a term of an account, not an actual coin.

Weight

The pound avoirdupois (lb) of 16 ounces (oz); 112lb making 1 hundredweight (cwt), and 20 cwt 1 ton (although the cwt may sometimes have still been calculated at 100lb as its name implies).

Linear

The league was generally accepted as 3 miles. The modern nautical mile was not yet established, and ‘mile’ is to be understood as the standard 1,760 yards.

Dates

The year of grace is reckoned from 1 January (and not 25 March as was usual in the sixteenth century), but dates are otherwise in the Old Style (i.e. not adjusted to the Gregorian calendar). The regnal years of Henry VIII are frequently used in the documents; the King’s accession day was 22 April, and the regnal year was calculated from that date, until 21 April following:

1 Henry VIII runs 22 April 1509–21 April 1510

10 Henry VIII: 22 April 1518–21 April 1519

20 Henry VIII: 22 April 1528–21 April 1529

30 Henry VIII: 22 April 1538–21 April 1539

38 Henry VIII: 22 April 1546–28 January 1547

Date formulae in Latin have been translated.

INTRODUCTION

Background

The Mary Rose was a ‘Great Ship’. She has become the symbol of Henry VIII’s navy, largely because a substantial part of her has survived, and was raised to the surface in a high-profile operation in 1982. She now has a museum dedicated to her, and her loss has been the subject of much scrutiny. This status, however, is appropriate for other than archaeological reasons. Her working life coincided almost exactly with the King’s reign, and when she was built she was of an innovative design, signalling Henry’s lifelong interest in fighting ships. She was the Dreadnought of her day.

In 1509 England was not a sea power, and had not been since the eleventh century. The reason for this was that the Norman and Angevin kings had also held substantial parts of France, and the English Channel was a highway within their dominions, rather than a defensive moat. This changed to some extent during the fourteenth century, and in the early exchanges of the Hundred Years War the English were alerted to the need for sea defences by a number of French amphibious raids on the south coast. In response, the English won their first major naval victory for 300 years at Sluys in 1340. This gave Edward III effective control of the Channel for a generation, but it did not change his strategic thinking, which continued to focus on winning pitched battles in France.

Edward, in fact, had no navy. He owned some ships, most notably the large cog Thomas, which served as what would later be called a flagship, but he raised a fleet when he needed one by the traditional methods. One of these was ‘Ship Service’, a feudal contract whereby certain port towns provided ships for the King’s service in return for their charter privileges. Another was a variant of the Commission of Array, when a nobleman or an experienced captain was authorized to ‘take up’ ships for the King’s service, for a given period and at a given price. This was possible because there was no significant difference between a warship and a merchant ship. The King maintained a stock of prefabricated wooden castles, which were added to the requisitioned ships to accommodate archers and other soldiers, and then removed at the end of the campaign. The advantage of this ad hoc approach was that it was cheap; not only did the King not have to invest in expensive ships, but the modest number of vessels he did retain could be serviced by a single officer, the Clerk of the King’s Ships. There was no permanent plant, and the regular workforce was confined to a handful of master mariners. The King used his own ships to trade, and to carry his ambassadors and messengers, but when not in use for his own purposes, they could be leased out at a profit.

The disadvantage, of course, was that it was inefficient. If a threat appeared quickly (that is, without at least three months’ warning), it was impossible to mobilize to meet it. No fleet could be kept in being for more than a short campaigning season, because the ships were needed for other purposes, and consequently ‘keeping the seas’ was an impossibility. There could be no defensive shield, and no means of protecting merchants against the depredations of pirates. Such a system was suitable if the only need was for an occasional ‘Navy Royal’ to escort a fleet of troop transports to France, and that was how Edward III operated it. The great victory at Sluys was little more than a happy accident; a chance encounter between two fleets which had been assembled for a different purpose.

The first signs of a more creative naval policy had come from Henry V in the early fifteenth century. Unlike Edward, Henry had some appreciation of the importance of sea power in its own right. He was also sensitive to the discontent that wholesale requisitioning bred in the merchant community, particularly in London, which was becoming a major factor in policy calculations. Moreover, Ship Service was in full decline as the original chartered ports lost their importance and the new ones negotiated different contracts. When Henry decided to renew the war with France in 1415, he therefore decided to build or purchase about thirty of his own ships, and to take up most of his transports in the Low Countries. He was, as is well known, spectacularly successful. His fleet was unchallenged and his armies victorious. His shipwrights also pushed their technology to its limits to build the massive Grace Dieu of 1,000 tons, once thought to have been a white elephant but now considered to have been useful as well as impressive. Its remains can still be seen in the Hamble estuary at low tide. However, Henry’s naval vision did not extend beyond the job in hand. As soon as the war was won, the fleet began to be dispersed, and after he died in 1422 it was run down almost to nothing, on his own instructions. By 1450, everything except one small balinger had either been sold or had rotted from neglect, and the office of Clerk of the King’s Ships was discontinued. In so far as Henry VI had a policy for ‘keeping the seas’, it was to privatize it, and a variety of methods was tried, including licensed self-help by the merchant communities of Bristol, Calais and London. Nothing worked, and the failure to control piracy resulted in the payment of substantial compensation in order to prevent diplomatic fallout. In 1449 a private fleet, under even less discipline than usual, attacked and plundered ships of the powerful Hanseatic League, and the price, both financial and political, was very high.

Edward IV, who secured the Crown in 1461, appreciated the problem, but it was not high on his list of priorities. He owned more ships than Henry VI had done, but left them in the care of ‘King’s shipmasters’, and used them almost entirely for trade. To the extent that the seas were kept, it was by the same shambolic methods as before, although the disasters were on a smaller scale and Edward did actually fight a full-scale war with the Hanseatic League on his merchants’ behalf. It could hardly be described as successful. Edward had no more idea of naval policy than his predecessors, but he did resurrect the office of Clerk of the King’s Ships in 1480, and that was to signify the beginning of a new situation. Edward died in 1483 in possession of about half a dozen ships, and the brief reign of Richard III, eventful as it was in some ways, merely saw that position maintained. When Henry VII came to the throne in 1485, he continued with Thomas Rogers in office as Clerk of the Ships, and seems to have taken a thoughtful look at his modest department. The results were not spectacular, but they were immediate. Within two years two large state-of-the-art warships had been built, the first in England. These were the Regent and the Sovereign, carracks of 600 and 450 tons respectively and of the latest Portuguese design. Both these ships could be (and were) used for trade, but they were primarily intended for fighting, and mounted large numbers of the small guns called serpentines. Henry had no intention of waging war if he could avoid it, so these ships were partly a deterrent and partly a statement of power. In them can be glimpsed the first signs of a long-term policy.

For the same reason, the construction of a dry dock at Portsmouth in 1495 was equally significant. Henry V had kept his ships at Southampton, but during the fifteenth century Portsmouth harbour had been minimally fortified to guard the anchorage against French attack. Henry VII extended those fortifications, and excavated a dock close to what is now the Old Basin. This was not in itself an innovation but the accounts of the work suggest that the new facility was intended to be permanent, and it may have been connected with the difficulty of docking the carracks in the traditional way, by beaching them. Henry built storehouses and a forge at Portsmouth, creating an embryonic naval base; and he also constructed some facilities at Woolwich, within easy reach of London. He did not, however, build or purchase a large number of ships. The Sweepstake and the Mary Fortune (both relatively small) were built in 1497, but when he died in 1509 he handed on just five ships to his son, fewer than he had himself inherited. Nor had he developed new methods of keeping the seas. His smaller ships could be, and occasionally were, used to chase pirates, but the great carracks were useless for that purpose, and he did not have enough vessels to make a real impact on the situation. What he did do was to provide armed escorts (at the merchants’ expense) on some occasions to ‘waft’ the Merchant Adventurers’ cloth fleet to Antwerp. He also revived the old bounty system, whereby merchants were paid so much a ton to build larger ships than they really needed, and to make those ships available for royal service when required. Piracy seems to have been less of a problem during his reign than it had been earlier in the century, but this was because the merchants started using a convoy system which made them less vulnerable to attack, rather than because the King was intervening effectively.

So Henry VII left a situation full of potential, but with very little achieved. His last Clerk of the Ships, Robert Brigandine, was a man of skill and experience, but more important, the new King had new ideas. Henry VIII was not an innovative thinker, and most of his original actions were the unintended consequences of trying to get his own way, rather than deliberately planned. However, he has an excellent claim to being the founder of the modern Navy, and the first thing he did was to build the Mary Rose.

Life on Board

The Mary Rose carried a crew which varied at different stages of her existence from 150 to 200 officers and men. In action she carried between 20 and 30 gunners, and between 175 and 220 soldiers. The proportions shifted over thirty-five years, but the total was always around 400. Before she was rebuilt in about 1536 there were rather fewer seamen and gunners, and rather more soldiers. The rebuild enlarged her, and increased the number of guns; moreover, changing tactics reduced the likelihood of hand-to-hand fighting. At the time of her loss she may have been carrying more than her normal complement, because not only would her officers have been attended by their own servants, but extra soldiers would have been taken aboard to help with the kind of action that was anticipated. The contemporary figure given for the loss of life was 500, and that was probably exaggerated, but not necessarily by much.

Some of the 400 shoes of differing styles and manufacture recovered during the excavation. (Stephen Foote)

The seamen wore woollen garments, breeches, tunics and caps, which they repaired themselves as the need arose. Although they had leather shoes which they wore on occasion, particularly ashore, wet and slippery decks meant that they worked most of the time barefoot. In anything like bad weather they must have been wet most of the time, because their rough garments would not have been waterproof. When times were good, and the pay was regular, most of them probably had spare clothes, stockings and undergarments. Such things were not luxuries, because of the living conditions, but times were sometimes hard, and both taverns and gambling houses took their toll of these items. The soldiers were similarly clad, but because they were not required to work the ship, they would normally have kept their shoes and stockings on. Armour, in the shape of morions and ‘almain rivetts’ (body armour) was kept in the ship’s armoury, along with the bows, arrows, hackbuts and other weapons. However, most of them probably possessed their own jacks, stout leather jerkins which gave reasonable protection if nothing else was available. The soldiers were also normally provided with tabards, or loose overgarments, in the Tudor uniform colours of green and white. The officers dressed in accordance with their status. The quartermasters, the boatswain, the cook and the carpenter, and probably the master gunner as well, would have ranked as yeomen on a big ship such as this, and would have worn clothes of better quality, but not very different in design. The higher officers, on the other hand, such as the captain, the master and the lieutenant, would have been gentlemen, and would have worn fine-quality wool of richer colour and design, with silks and velvets for special occasions. All ranks would have worn such personal adornments and jewellery as they could afford, and often carried their spare cash (if any) in this form. The captain and the master had quite spacious cabins, but lesser officers, such as the surgeon and the carpenter, had little cubbyholes, and the men, seamen and soldiers alike, slept wherever they could find space for a straw palliasse, and kept their modest belongings in portable chests. It would be nearly a century before hammocks came into general use.

Part of the extensive collection of tableware recovered, including pewter and wooden flagons and a pepper-mill. (Mary Rose Trust)

Food was always a problem, and drink even more so. The victuallers needed to be watched like hawks to ensure that they provided full measure, and did not recycle old stock. Ships like the Mary Rose, which rarely left home waters and were seldom at sea for more than two or three weeks at a time, had nothing like the difficulties suffered by the longer voyagers of later in the century, but it was tough enough. It was hard to find supplies until the system was reorganized after 1550, and harder still to get the supplies to where they were needed. The standard diet was simple, and reasonably nutritious, but it was dull and lacked certain vital ingredients. The main provisions were bread, or biscuit, cheese, butter, bacon, salted beef, dried or salted fish, and beer. The rations allowed were ample, but the absence of fresh fruit and vegetables encouraged diseases such as scurvy, and both the biscuit and the beer tended to deteriorate rapidly, even if they were shipped in good condition. The pursers of individual ships made their own supplementary purchases, and the officers and their servants bought their provisions to suit themselves. Consequently, the presence of fruit stones and chicken bones among the detritus of the wreck does not prove that such superior rations were on general offer. Food was prepared in a galley, and cooked in a massive brick oven housed in the bowels of the ship, where the almost permanent fire not only guaranteed hot meals (a very important consideration), but also enabled wet clothes to be dried when there was no sun on deck. These ovens were a feature of all large ships, and needed very careful and skilled management if disaster were to be avoided.

A precise replica of the brick galley found on board. This reconstruction and experimental archaeology have shown that the structure was adaptable enough to cook plain fare for the crew and finer meals for the officers. (C.T.C. Dobbs/Mary Rose Trust)

A large warship such as the Mary Rose carried a barber surgeon, who also had to double as a physician, and the formidable equipment of this gentleman is one of the best-known features of the Mary Rose Trust’s museum. He was there primarily, of course, to treat the injuries suffered in battle, but it is clear that he also had a general responsibility for the health of the crew. Tudor medicine was primitive, but not totally ineffective, and there are very few references to outbreaks of disease on this ship. We know that plague broke out on Lord Lisle’s ships in 1545, and even more severely at the end of the Armada campaign, but there are no records of similar outbreaks on the Mary Rose during its working life. This has probably got most to do with never operating far from base, and putting sick men ashore as soon as their condition was known, but it may also have been a result of generally good discipline. Hygiene was little understood in theory, but an experienced seaman knew that keeping himself and his immediate environment as clean as possible was the best way to stay healthy. With so many men cramped together, waste disposal of all kinds must have required constant vigilance. There was no difficulty about where to put it – it went over the side – but making sure that the containers were regularly emptied, and cleaned after use, must have been one of the ship’s more necessary and less desirable jobs. Even so, there were limits to what could be achieved. It’s known that the ship had rats and that the men had fleas, but that would have been equally true of houses ashore. By modern standards the living conditions would have been squalid; but as the men did not desert, and showed no marked reluctance to serve in her, it must be assumed that she had the reputation of being a reasonably good ship.

Although a carrack was a labour-intensive ship, the men did not spend all their time at work or asleep. Apart from the officers, very few would have been literate, but the survival of dice, gaming boards and musical instruments provides evidence of how they passed their leisure time. It is also clear that many of them were devout. Rosary beads and small votive objects testify to a flourishing traditional piety. There was probably no priest on board the Mary Rose when she sank, but that would have been because she had only just left harbour, and was not expected to be out for long, rather than because there was no need of one. Normally a large ship that was to be at sea for more than a few days would have carried at least one cleric, capable of saying mass, hearing confessions and administering the last rites. There would have been no specially dedicated place for the performance of these rituals; a space was cleared on an appropriate deck when any significant number of men gathered together for that purpose. When the remains of one of those who perished in the wreck had been recovered, he was appropriately interred in Portsmouth Cathedral with the Sarum rite in use in 1545.

The Ship

The Mary Rose was a four-masted ship, of the type known as a carrack. This design had been pioneered in the previous century by the Portuguese, and was used particularly for their large East Indiamen. The main characteristics of the carrack were its deep draught, and its high-built castles, fore and aft. In the days before the general use of heavy guns, these castles were valuable bases from which to launch boarding attacks down onto an enemy deck, and were easily defensible. Carracks still had their advocates as late as the end of the sixteenth century, because they were so hard to board. At the same time, the castles made them unweatherly, and difficult to handle in a high wind. The praises heaped on the sailing qualities of the Mary Rose were relative, and should be taken with a pinch of salt. This design was not new to England, as the Regent and the Sovereign had pioneered it over twenty years previously, but there do seem to have been some new features. It is now thought that the Mary Rose, unlike its predecessors, was carvel-built from the start, that is to say that the planking of her hull was laid edge to edge and caulked, instead of overlapping, or clinker-built. Such a method was not traditional to northern shipwrights, and had been borrowed from the Mediterranean. To accommodate the guns listed in the 1514 inventory, she must have been built with a number of gunports. Such ports create difficulties in a clinker-built ship, where the hull depends for its strength very largely upon the integrity of its planking shell. However, they raise no problems with a carvel build, because the strength derives entirely from the frame.

The burthen of the original ship was somewhere between 500 and 600 tons. It is difficult to be sure because, of course, the surviving hull is that reconstructed in about 1536. This ‘new building’ seems to have been fairly drastic but (as was often the case) not to have resulted in what was effectively a new ship. The tonnage was increased to about 700, but this does not appear to have been achieved by lengthening or widening the hull. Rather, the hull seems to have been strengthened, a substantial number of new gunports added, and the castles raised. The result was to make the Mary Rose a much more formidable fighting machine, but to reduce her sailing qualities still further. She may have become less tolerant of extreme angles of heel, or shifts in the distribution of weight, and it is perhaps significant that there was no further praise of her handiness after the rebuild. Instead, on 18 April 1537 Vice-Admiral John Dudley reported to the King that some of his ships were proving unweatherly, and that ‘the ship that Mr Carew is in’ was a particular offender, which might have to be withdrawn. George Carew was captain of the Mary Rose at the time of her loss eight years later, and Dudley clearly thought that his news would upset the King. None of this proves that the unweatherly ship was the Mary Rose, but the King might well have been upset to discover that he had ordered modifications to a prized ship which had made her potentially vulnerable.

We have ordnance inventories for both 1514 and 1546 (the latter being the Anthony Roll, compiled the year after the sinking), so it is relatively easy to work out what difference the rebuilding had made to the ship’s firepower. In 1514 she carried 77 guns, but only 6 can be classed as anti-ship rather than anti-personnel weapons: the 5 great curtals and 1 murderer. In the 1546 inventory she is listed with 91 guns, of which 26 can be classified as anti-ship; these comprise 14 cast-bronze guns from the cannon and culverin classes, and 12 large wrought-iron port-pieces. All were put on board after 1535, because they bear subsequent dates. However, the Anthony Roll inventory may not be an accurate record of the armament on board when the ship was lost. She was also there said to be carrying 250 longbows (as opposed to 123 in 1514), 50 handguns (or hackbuts) and 30 swivel guns.

For about three years the Mary Rose was the ‘star’ of Henry VIII’s navy. She was not the largest ship, but she was new and state-of-the-art. Then in 1514 she was eclipsed (too late to affect her role in the war) by the massive Henry Grace à Dieu of 1,200 tons. Thereafter, this ship, popularly called the Great Harry was the natural flagship when the navy was deployed at full strength. However, she was too large, and too expensive, to be used for routine duties, and the Admiral’s flag continued to be carried on the Mary Rose for many operations. In spite of her rebuild, she was no longer a modern ship by 1545, and was just one of six or eight large warships which the King could deploy, but Henry retained a soft spot for her, and was considerably upset by her loss.

The Letters

At the core of this collection are twenty-one letters (beginning with 12) and one other document (34) specifically dated aboard the Mary Rose on active service during the wars of 1512–14 and 1522–3. Another seven letters are presumed to have been similarly written; a few related despatches are also included. All this material is printed in full, much of it for the first time. There are no letters from the Mary Rose during her last campaign in 1545; we do, however, have several concerning the original salvage attempt, from which all relevant extracts are given here. Of the mass of accounts, warrants, bills and other documents in which the ship is mentioned, we can present only a representative selection. Almost all the texts here are taken from original manuscripts in the Public Record Office or the British Library. With a few exceptions (7, 44, 57–8) these sources are calendared in the Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII, published between 1862 and 1932, or in other guides to the State Papers. Those versions are, necessarily, only editorial summaries of the letters, and much more abbreviated listings of the accounts and other papers. A few of the early letters were printed in full and in original spelling by Sir Henry Ellis in his Original Letters Illustrative of English History (1824–46). Some were similarly given by Alfred Spont in Letters and Papers Relating to the War with France, 1512–13, issued by the Navy Records Society in 1897; Spont also included many documents from the French archives, not in Letters and Papers … Henry VIII. A collection of documentary and literary sources for the history of the Mary Rose herself was first assembled by S. Horsey; his Narrative of the Loss of the Mary Rose was published at Portsea in boards made from timber recovered from the wreck. The original edition is dated 1842, but appears to have been issued two years later. An undated ‘second edition’ (identical in content but in larger format) followed. Horsey received assistance from Sir Frederic Madden, Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Museum, and himself a Portsmouth man. Madden was to be instrumental in securing for the Museum the second section of Anthony Anthony’s illuminated inventory of Henry VIII’s fleet and its ordnance, completed in 1546. The first section of this MS, now in the Pepysian Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge, contains the only contemporary illustration of the Mary Rose (58 and colour plate 4–5). Horsey’s little book was reprinted by the Clarendon Press, Ventnor, in 1975, but has long been unobtainable.

An inkwell made of horn, recovered from the wreck. (Mary Rose Trust)

While the present edition is indebted to these earlier works, it aims to make a much larger body of material more widely accessible. All the texts are given in modern spelling, including place and personal names where established; this treatment is used for the extracts from contemporary printed books as well as in transcribing the MSS. In making these modernized versions, all the originals have been consulted, and occasional improvements have been made to the texts given in Spont and elsewhere. A few simple archaic forms (as ‘hath’, ‘cometh’) are retained where they do not readily convert to the rhythms of the modern language, or if (as ‘Hampton’ for Southampton, ‘Preer John’ for Prégent de Bidoux) colloquialisms remain appropriate. Words confidently supplied because of damage to the MSS are printed in roman type within square brackets. Words in italic within square brackets are editorial insertions which identify individuals or places, explain what may be unfamiliar in vocabulary, or supply what may be defective or difficult in the syntax. Italic is also used for words which can only be conjectured from a damaged original. Otherwise dots are used within square brackets to show where text is lost. This applies particularly to the several letters from the British Library’s Cotton MSS, which have been severely cropped by fire. Wherever the bracketing indicates that only a part of a word can now be read, the arrangement can often be only approximate because of the modernization of the spelling. Dots not within brackets indicate editorial omissions. MS deletions and insertions are indicated only where the changes are substantive.

A Key to Documents (Appendix I) gives the MS and other bibliographical references. The List of Persons (Appendix II) provides biographical notes for many of the individuals mentioned; briefer identifications are given in the Index. The Glossary (Appendix III) explains technical terms.

1

THE BUILDING AND EQUIPPING OF THE SHIP (1510–14)

Commentary

It is not known exactly when, where, or by whom, the Mary Rose was built. There is a reference to four unnamed ‘new ships’ being fitted out at Southampton in December 1509, and if the Mary Rose was one of them, then she must have been laid down before April 1509; in other words the decision to build her must have been taken by Henry VII rather than Henry VIII. However, it is probable that these were much smaller vessels, and that the true date of the laying down of the Mary Rose and her sister ship the Peter Pomegranate was January 1510, represented by the warrant of the 29th (1). Neither ship is named, for the simple reason that names would not have been given at this early stage. Nor do the tonnages match those ultimately achieved; as they were eventually launched the Mary was about 600 tons and the Peter about 450, but tonnage measurement was notoriously inaccurate at that date, and if the ships were still in building the burthen was probably mere guesswork. The warrant, of course, does not represent more than a small fraction of the cost, and the reference to rigging suggests that the building was already well advanced. Ships of this size cost in the region of £3,000 at this time, a figure which should be multiplied by 1,000 to get an approximate modern equivalent. At a time when the King’s ordinary annual revenue was about £100,000 a year, they represented a substantial investment. This cost would have been met by a series of warrants of this kind, drawn on a variety of different revenue sources. This one is an assignment on the customs revenues of the port of Southampton, but others would been assigned on London, or drawn directly from the Exchequer or the Duchy of Lancaster.

Southampton was convenient, because honouring the assignment would have meant transporting cash in the shape of gold or silver coin, and it is almost certain from later references that the ships were built at Portsmouth. Robert Brigandine had been Clerk of the King’s Ships since 1495, and knew most of what there was to know about the business. He was not trained to the sea, but had begun his career as a minor officer of the royal household. Henry VII had relied on him for advice on all matters relating to the ships, and he was clearly responsible for the building of the Mary and the Peter, but exactly what that meant is more difficult to say. Brigandine paid the bills, but he was not a master shipwright. Whether he was responsible for the design, and the shipwrights worked to his instructions, or he was merely the site manager and the shipwrights themselves were responsible for the design, we do not know. The latter is more likely, because they would have lacked the status to claim the credit – and as far as we are aware, no one ever did. Brigandine divided his time between Portsmouth and Woolwich, but was increasingly located at the former, and seems to have been working there throughout the time when these ships were being built.

It is reasonable to deduce that Portsmouth was the principal royal dockyard at this time, because work on the Regent and the Sovereign, both large warships and about twenty years old at this point, was being carried out at the same time, and also under Brigandine’s supervision. The indenture, or contract, over which the Clerk was concerned in June 1511 (2) probably marks the end of the construction process. The sum of £1,075 14s 2d may well represent the whole cost of renovating the older ships, but £1,016 13s 4d would have been only the last instalment for the new constructions (3). The warrants for the balance do not appear to have survived. When the Peter was first launched, she seems to have been very similar to the Sovereign, and designed in the same way to carry a substantial number of small guns. It was only later that she was rebuilt to carry heavier weapons. The Mary, however, carried heavy guns from the start; not many, probably six or eight, but they necessitated a design feature which was new to the point of being revolutionary – the gunport. Whether she was actually the first warship to be built in this way, is not known; nor who was responsible for the idea. Ports had been used for loading purposes before, and seem to have originated in Brittany. It has been suggested that the King himself insisted on the Mary being built in this way, and his known interest in both ships and guns makes that plausible; but Henry is not known for being inventive, and it seems likely that he got the idea from somewhere else, most likely France, although it is possible that he was already emulating his brother-in-law James IV of Scotland, as he was to do in 1514 with the Henry Grace à Dieu.

Although there is no record of the launch, it clearly occurred in the summer of 1511. The ships would have been named at that time; by 9 June they are known as the Mary Rose and the Peter Pomegranate. It was quite usual to give ships the names of saints, and in this case such names seem to have been combined with two well-known Tudor badges, the rose for the King and the pomegranate for the Queen. It is also possible that the former name was a recognition of the fact that the Virgin was traditionally known as the ‘mystic rose’. It is often said that the ship was named after, if not actually by, the King’s sister, but there is no evidence for this.

The Tudor rose, surrounded by the Garter and topped by the closed imperial crown; with, below, the King’s monogram ‘HR’ (‘Henricus Rex’). This mark of royal ownership appears on this demi-cannon recovered from the Mary Rose. (Mary Rose Trust)