Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

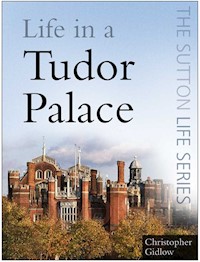

Take a tour with the author round a courtly palace and see what the kitchens, the bakery, the laundry, the bedrooms, the gardens and the privvies were like. Everything you could wish to know is here, as the book describes the different lifestyles of the court, and the people who served them.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 82

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Life in a Tudor Palace

Life in a Tudor Palace

Christopher Gidlow

First published in 2007

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© Christopher Gidlow, 2007, 2011

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Christopher Gidlow has asserted the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7061 0

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7062 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

1 Introduction

2 The Tudor Court

3 A Day at the Tudor Palace

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

The reign of King Henry VIII was one of the great dramas of English history. As often as not this drama was played out on the magnificent stage provided by his palaces.

By inheritance, confiscation and construction, King Henry amassed some sixty residences, of which two-thirds were in regular use. They ranged from ancient castles (Windsor and the Tower of London), rambling hunting lodges (Woodstock) and glorified manor houses (Eltham), to newly constructed Tudor palaces such as those at Nonsuch, Hampton Court and Whitehall.

Among these many residences seven stood out, the so-called ‘Great Houses’, at Greenwich, Westminster/Whitehall, Hampton Court, Woodstock, Richmond, Eltham and Beaulieu. It is on life in these Tudor palaces that this book focuses.

These palaces were symbols of Henry VIII’s power and magnificence, and also practical bases from which he could govern the kingdom while enjoying his favourite pastimes. They were residences, too, of the extensive Tudor Court. The court existed to serve the king, from the ‘gong-scourers’ who cleaned out the toilets, to the Lord Great Master, one of the highest nobles in the land.

The palaces of Tudor England have all but vanished, victims of accidental fires or changes in taste. The Great Halls of Eltham and Westminster, already old in Henry’s time, still stand, if in much altered surroundings. Only at Hampton Court do substantial remnants of the main apartments, courtiers’ lodgings and the kitchens that served them survive to be visited. Even here, the private chambers of the king and his family have vanished.

For evidence, we must search the account books, which record the vast expenditure lavished on the buildings and the food and wages of those who worked within. Detailed inventories of the palaces taken on Henry’s death offer tantalising glimpses of the mundane and the magnificent objects that filled them. Additionally, ambassadors and courtiers themselves left accounts, which illuminate life within the walls.

We have one very significant piece of information on how a Tudor palace functioned. In 1527, King Henry VIII and his Council (which in practice meant his all-powerful Lord Chancellor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey) issued the Eltham Ordinances. These were detailed rules for ‘the establishment of good order and reformation of sundry errors and misuses’ in the court.

The Ordinances, in a bound volume, signed by the king, were kept in the Compting House, the office of the palace accountants. Here they could be consulted regularly by the head officers of the chamber and household. The councillors would make quarterly inspections of the palaces to ensure the Ordinances were being kept.

These Ordinances provide an invaluable record of how the meticulously minded cardinal wanted the court to function, with the minimum of mistakes and unnecessary waste. In reality, the court was dynamic and fluid, dominated by the changing whims of the largerthan-life monarch and the personalities who surrounded him. The great cardinal himself lost power barely two years after the Ordinances were drawn up. We can see in them, however, both the theory he had tried to impose and the problems that could arise to challenge it.

We shall follow King Henry VIII and his court through a typical day at a Tudor palace, between the publication of the Ordinances at Eltham Palace in 1527 and his death at Westminster/Whitehall Palace in 1547. In practice there was no such thing as a ‘typical’ day over that period, which encompassed six wives, the fall and execution of numerous ministers, a split with Rome and the physical degeneration of an ageing, ailing monarch. We shall imagine, though, a day that was not a particular feast day, one without any specific great business to attend to or important visitors to be received; a very ordinary day, of which most of the history of the time must have been composed.

CHAPTER 2

The Tudor Court

The way a Tudor palace worked derived from the much simpler pattern of noble life in the Middle Ages. The main building used by a medieval noble was the Great Hall. This was used for public life, eating and as a place where servants could sleep. At the back of the hall would be a separate room, a chamber, in which the lord would sleep, conduct private business and be entertained. At the opposite end you would find separate kitchens, stables and stores.

The hall and its dependencies were the responsibility of the Steward, while the chamber was the domain of the Chamberlain.

This traditional structure continued, in a magnified and more complex form, in the Tudor palaces. Here, the Lord Steward presided over the household, the Great Hall and the departments necessary to its functioning, while the Lord Chamberlain looked after the ‘chamber’, aspects of the king’s private life as well as his actual bedroom.

The buildings where the court resided were largely incidental. The structure remained the same, whatever its physical surroundings. The king travelled from residence to residence. His favourite palace was Greenwich. Business kept him at Westminster or the neighbouring Whitehall for much of the year, and Windsor Castle was his principal residence outside London. Next in favour came the newly built Hampton Court Palace.

The court arrives

The Tudor palaces were massive complexes, which dominated their surrounding areas. Towers, pinnacles, chimneys and vanes signalled their presence from afar.

The first warning that the king was on his way would be the harbingers galloping into view. Led by the knight harbinger, these men were responsible for preparing the king’s arrival and assigning lodgings for the courtiers who accompanied him. Shortly afterwards, the gentlemen ushers and yeoman ushers would arrive.

The harbingers and ushers had with them a book, signed by the king,‘describing the number of every person, of what estate, degree or condition he be’ who was allowed to lodge in or around the palace. They were ordered, on pain of losing their offices, not to give lodgings to anyone else unless directed by the king or council. If there were more courtiers than the palace could accommodate, local householders might be compelled to offer hospitality. The ushers would take note of what items were left in the lodging and take charge of the keys. Householders were paid double compensation for any losses caused by thoughtless young nobles making free with their property.

The palaces had ‘abiding households’ that looked after them while the king was elsewhere. Although it was possible for the court to arrive unexpectedly, in practice its movements were fairly regular. The king tended to stay in Whitehall for the law terms, when Parliament sat. Itineraries were worked out in advance, with the court moving every few weeks in summer. In the winter, it might move even more frequently, except when hindered by the weather. Even the best plans could be thrown into disarray by an outbreak of plague, forcing it to move swiftly to a more healthy location.

A Tudor would not have wondered why the court moved. This had been the regular custom for as long as there had been kings. One reason was the demand the court placed on its location, devouring food stocks, over-hunting the parks and monopolising lodgings. Another was for the king to display himself to his subjects. Although moving the court was difficult, it was easier for the king to move to meet his people than for them to travel to see him. We can also imagine that a change of scene simply added to the king’s enjoyment of life, preventing him from getting too bored.

An important early arrival was the clerk of the market. He would note local economic conditions, then set ‘convenient and reasonable’ prices for food and drink, fodder, lodging and bedding. He would check local weights and measures and source seasonably good and wholesome provisions. This was an important safeguard, since otherwise prices would be bound to rise with the arrival of so many wealthy consumers.

Soon the road leading to the palace would be creaking with the carts of the Lord Steward’s men. The offices, as the different departments were called, had their own staff and equipment carts. Their job was to set up the kitchens so that there would be food waiting when the rest of the court arrived.

There was always work to be done to make the palace ready. Carpenters, joiners, masons, painters and other craftsmen worked swiftly, going from chamber to chamber. The accommodation would be swept, washed and dusted. Unforeseen circumstances gave rise to extra work. For example, before the first arrival of Queen Anne Boleyn at Hampton Court, craftsmen laboured through the night removing all references to Catherine of Aragon. Three years later they had to repeat the process, replacing Anne’s decorations with ones relating to Jane Seymour!