Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pitkin

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The word 'workhouse' has a grim resonance even today, conjuring up a vision of the darker side of Victorian Britain. Almost every town had at least one workhouse, and most people dreaded ending up there. Here we examine how workhouses came into being, what life was like for men, women and children on the wrong side of the poverty line, and how social attitudes evolved through the momentous events of Victorian Britain into the 20th century. Illustrated from contemporary and modern sources, this fact-filled guide presents an intriguing picture of a world of steam engines, self-help, service and salvation - where workhouse life, and workhouse reform, influenced attitudes and services we now take for granted.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 50

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

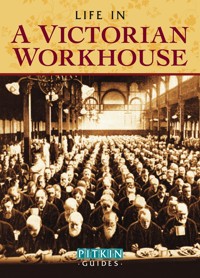

LIFE IN

A VICTORIAN

WORKHOUSE

FROM 1834 TO 1930

PETER HIGGINBOTHAM

Pitkin Publishing

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

Text © Pitkin Publishing, 2011, 2012, 2013

Written by Peter Higginbotham. The right of the Author, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978-0-7524-8697-0

MOBI ISBN 978-0-7524-8696-3

Original typesetting by Pitkin Publishing

CONTENTS

Important Dates

The Workhouse

Origins of the VictorianWorkhouse

Entering and Leaving theWorkhouse

Workhouse Buildings

Daily Life

Workhouse Labour

Workhouse Food

Children in the Workhouse

Workhouse Medical Care

Old Age and Death

Tramps and Vagrants

Running the Workhouse

Ireland and Scotland

The Workhouse inLiterature and Art

The End of the Workhouse

Places to Visit

Glossary

FRONT COVER: The dining hall at London’s St Marylebone workhouse in around 1900.

IMPORTANT DATES

1536 Dissolution of the monasteries begins – religious houses provided for the poor.

1601 The Poor Relief Act makes parishes responsible for poor relief in England and Wales.

1795 The ‘Speenhamland system’ links labourers’ minimum wages to the price of bread.

1834 The Poor Law Amendment Act creates a new poor relief system based on union workhouses.

1837 Civil registration of births, marriages and deaths begins, administered by Poor Law Unions.

1838 The Irish Poor Relief Act introduces the union workhouse system into Ireland.

1842 Some unions allowed to give ‘out relief’ to able-bodied men in return for work.

1845 The Scottish Poor Law Act passed. Start of the Great Famine in Ireland. A scandal erupts over conditions at the Andover workhouse.

1847 The Poor Law Commissioners replaced by the Poor Law Board. Married couples over the age of 60 in a workhouse can request a shared bedroom.

1867 The Metropolitan Asylums Board created to provide care for London’s paupers with infectious diseases or mental impairment.

1871 The Poor Law Board replaced by the Local Government Board.

1900 A major overhaul of workhouse diets implemented.

1905 A Royal Commission appointed to review the poor relief system.

1909 Old Age Pensions introduced for the over-70s. The 1905 Royal Commission’s reports published.

1913 Workhouses become officially known as Poor Law Institutions. Children to be removed from workhouses by 1915.

1919 Poor relief administration passes from the Local Government Board to the Ministry of Health.

1930 The Local Government Act abolishes existing poor law authorities. Local councils now administer ‘Public Assistance’.

1948 The National Health Service Act comes into operation on 5 July.

THE WORKHOUSE

The Victorian workhouse is an institution whose powerful image lingers on deep in the minds of many people in Britain, even those born long after it was officially abolished more than 80 years ago. Why should this be? As this guide reveals, the workhouse touched many lives. For those inside the workhouse, entering its doors carried an enormous social stigma that today is hard to imagine. For the elderly, the workhouse gained a reputation as a place that you never came out of – except in a coffin for burial in an unmarked pauper’s grave.

A very large proportion of the population had some kind of connection with the workhouse. If they were not living inside it, they were paying for it through the poor rates, supplying it with goods, or buying the firewood the inmates had chopped.

The workhouse was also a highly popular subject for artists, poets, journalists and novelists, most notably in Charles Dickens’ tale of workhouse boy Oliver Twist, first published in 1837, the year that Queen Victoria came to the throne. What went on behind the doors of the workhouse held such a fascination for the Victorians that a whole succession of middle-class ‘social explorers’ clothed themselves in dirty old rags to gain admission for a night’s stay and to witness conditions for themselves.

• But what was the workhouse really like?

• Who were its inmates?

• Why and how did they enter the workhouse?

• How did they spend their time?

• How did they ever get out?

• When did the workhouses close?

• And what happened to the buildings?

To these, and many more questions, this guide provides the answers.

ORIGINS OF THE VICTORIAN WORKHOUSE

Before their dissolution by Henry VIII in the 1530s, England’s monasteries and religious houses had long provided help for the poor, the elderly and the sick. In the decades that followed, the burden of assisting such people was increasingly placed on the better-off members of the community, the landowners and householders. In 1601, the Poor Relief Act formalized how the poor were now to be provided for.

The system adopted, often known as the Old Poor Law, revolved around the parish, the area served by a single priest and his church. Every householder was required to contribute to the poor rate, an annual tax based on the value of their property. The poor rate was mostly distributed as ‘out-relief’ – handouts to individuals as money, food, clothing or fuel. The ‘undeserving’ able-bodied poor were expected to work in return for poor relief, with stocks of materials such as wool or flax being bought for this purpose. The poor rate could also be spent on housing the so-called ‘impotent poor’ – the old, the lame, the blind – who could not work.