18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

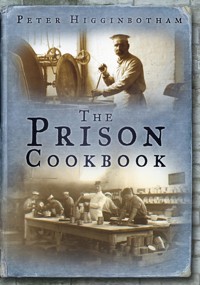

This copiously illustrated book takes the lid off the real story of prison food. Including the full text of an original prison cookery manual compiled at Parkhurst Prison in 1902, it examines the history of prison catering from the Middle Ages (when prisoners were expected to pay for their own board and lodging whilst inside) through the Newgate of the Victorian age and on to the present day. With sections on prison life, punishments, the food on board transportation vessels and floating prison hulks, and the work of reformers such as John Howard and Elizabeth Fry, who vastly improved the conditions of those who were put behind bars, this evocative and unique book shows the reader exactly what 'doing porridge' entailed.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

THE

PRISON

COOKBOOK

THE

PRISON

COOKBOOK

PETER HIGGINBOTHAM

Front cover illustrations: (upper) Gloucester prison kitchen; (lower) Rochester kitchen; both photographs reproduced with the kind permission of the Galleries of Justice.

First published 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Peter Higginbotham, 2010, 2013

The right of Peter Higginbotham to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9679 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Weights, Measures and Money

one

Introduction

two

Prison and Other Punishments

three

Early English Prisons

four

Life in Early Prisons

five

Prison Reforms

six

Transportation and the Hulks

seven

Prisoners of War

eight

The Evolution of Prisons 1780s–1860s

nine

Changes in Prison Food 1800–1860s

ten

The Victorian Prison Kitchen

eleven

Towards a National Prison System 1863–1878

twelve

From Worms to Beans

thirteen

The Prison Cookbook

fourteen

Prisons Enter the Twentieth Century

fifteen

Prison Food After 1900

Manual of Cooking & Baking

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Weights, Measures and Money

Below are some older measures and monetary units found in this book, with their approximate metric or decimal currency equivalents. Common abbreviations are given in brackets.

Weight

1 drachm (drm)

1.8 grams (gm)

1 ounce (oz)

16 drachms

28.4 grams

1 pound (lb)

16 ounces

450 grams

1 stone

14 pounds

6.3 kilograms (kg)

1 hundredweight (cwt)

112 pounds

50 kilograms

Volume

1 fluid drachm (or dram)

3.55 cubic centimetres (cc or ml)

1 fluid ounce

8 fluid drachms

28.4 cubic centimetres

1 gill (or noggin)

5 fluid ounces

143 cubic centimetres

1 pint (pt)

20 fluid ounces

570 cubic centimetres

1 quart

2 pints

1.1 litres

1 gallon

8 pints

4.5 litres

1 peck

2 gallons

9 litres

1 bushel

8 gallons

36 litres

1 firkin

9 gallons

41 litres

1 hogshead (of beer etc)

(originally) 52.5 gallons

239 litres

1 pipe

(typically) 2 hogsheads

479 litres

1 tierce

⅓ of a pipe or 35 gallons

160 litres

1 puncheon

cask of 72–120 gallons

327–545 litres

Length

1 inch (in)

2.5 centimetres (cm)

1 foot (ft)

12 inches

30 centimetres

1 yard (yd)

3 feet

90 centimetres

1 mile

1760 yards

1.6 kilometres

Money

1 penny (d)

0.4 pence (p)

1 shilling (s)

12 pennies

5 pence

1 mark

13s4d

67 pence

1 pound (£ or l)

20 shillings

1 pound

In terms of its purchasing power, £1 in the year 1750 would now (2009) be worth around £139. In 1850 £1 would now be worth around £83.

one

Introduction

The dietary has an intimate relationship with all the other elements of prison life. On its proper adjustment to the requirements of the average prisoner, and the manner of its application and administration, must depend in large measure the successful working of the whole prison system. (Departmental Committee on Prison Dietaries, 1899)1

‘Food’, commented one prison governor, ‘is one of the four things you must get right if you like having a roof on your prison.’ (National Audit Office, 2006)2

Putting people behind bars has a very long history. In a Bible story dating from around the seventeenth century BC, the book of Genesis tells how Joseph, a young Hebrew enslaved in Egypt, was consigned to the Great Prison at Thebes for attempting to seduce the wife of his master Potiphar. The prison was probably a granary where foreign offenders were held and required to perform hard labour.3 Today, prison has never been so popular – across the world, more than 10 million people are currently locked up.4

Being in prison, though, has not always been seen as a punishment in itself. In the past, it was more often used as a means for holding people securely until their trial or until their sentence was carried out. In early Rome, for example, debtors could be held in custody by their creditors for sixty days. Then, if still unable to pay, their fate would probably be slavery or execution by such means as burning, hanging, decapitation or clubbing to death. Justice in ancient Athens largely favoured retribution in the form of punishments such as stoning to death or throwing an offender from a cliff, with prison mainly used to confine debtors or those awaiting trial or execution. The Greek philosopher Plato, in a remarkably prescient view, proposed three new types of prison: a general prison to confine lesser offenders for up to two years; a more isolated centre where more serious but reformable cases were held for at least five years; and a remotely located institution where incorrigible offenders were held for life, without contact with other prisoners or visitors.5

Whatever the reason for someone being in prison, it has rarely been intended to be a comfortable or pleasant experience. Rome’s ancient Carcer, a group of prison buildings near the Forum, included quarry prisons and the subterranean Tullianum, where Saints Peter and Paul are said to have been held. According to the Roman historian Sallust, the Tullianum’s ‘neglect, darkness, and stench made it hideous and fearsome to behold’.6

Many ancient prisons were, by modern standards, quite small and the health of the inmates – let alone their comfort – was of little concern to those who ran them. Living conditions for those held in early English prisons were often little better. For a long period, they were privately operated with the inmates paying for their own food and accommodation. For those who could afford it, prison could indeed be a relatively painless experience, with a comfortable room and meals bought from the gaoler, cooked themselves or sent in from outside. But for those with little or no money, especially those being held for non-payment of their debts, prison life frequently consisted of a bed on the floor of a dark and damp cellar and a diet of bread and water. Even those found totally innocent of their charges could sometimes remain in gaol indefinitely because they could not pay the necessary release fees.

The so-called ‘Prison of Socrates’ in Athens where, according to popular tradition, Socrates was held while awaiting his execution. He refused the advice of his friends to try and escape and suffered the Athenian penalty of compulsory suicide by drinking a brew containing the poison hemlock.

The Tullianum in Rome, later known as the Mamertine prison. Originally, the only means of access was via a hole in the ceiling. Tradition has it that while the Apostle Peter was confined here, a spring of water miraculously appeared in the floor with which he was able to baptise his gaolers and forty-seven companions.

From the 1770s, reformers such as John Howard, Elizabeth Fry and James Neild exposed the iniquities of the English prison system and campaigned to make prisons more humane, often harnessing the power of public opinion to persuade prison operators to grudgingly fall in line with gradual legislative reforms.

In more recent times, even after the state had taken over the running of the country’s prisons in 1877, providing inmates with a bed of bare planks and a meagre diet of bread, porridge or gruel, and occasional potatoes, was still viewed as part of the deterrent value of a prison sentence. Faced with such treatment, it is perhaps not surprising that convicts at Dartmoor in the 1870s resorted to eating dead rats and mice, grass, candles, dogs and earthworms.

Attitudes gradually changed, however, and by the end of the nineteenth century, prison conditions, and particularly food, started to improve. The 1899 Departmental Committee on Prison Dietaries acknowledged that food was a core element in successful prison operation. A new national prison menu saw the inclusion of items such as beans, bacon, suet pudding, tea and cocoa, while the fare provided for prisoners who were sick soon included chicken broth, fishcakes, boiled rabbit, custard pudding and stewed figs. For inmates who misbehaved, however, the result would still be a spell on bread and water. At the same time, increasing concern for how food was prepared resulted in the introduction of training courses for prison cooks and the publication in 1902 of the first prison cookbook – the Manual of Cooking & Baking for the Use of Prison Officers – which is reproduced in full as part of this book.

From the 1950s, prison food began to change out of all recognition with the arrival of sausage, bacon and fried bread for breakfast, and of roast beef, roast potatoes, Yorkshire pudding, bread-and-butter pudding and custard on the dinner menu. Nonetheless, during the 1970s and ’80s, ‘inedible and monotonous’ food was still reported as one of the causes of dissatisfaction which led to a rash of violent disturbances and damage to prison buildings costing many millions of pounds.

By 2005, prisoners could select their meals from a multi-choice menu featuring dishes such as grilled gammon, chicken chasseur, or minced beef lasagne served with garlic bread and salad, with options catering for vegans, vegetarians, and a wide variety of religious and cultural diets. Porridge, the prison’s signature dish, had virtually disappeared. Clearly, the prison authorities had taken to heart the maxim of food (along with mail, hot water and visits) being the things you have to get right if you want to keep a roof on your prison.

The kitchens at Holloway prison in about 1901 when the Manual of Cooking & Baking was being compiled. Food was served in a two-piece metal ‘pail’ or ‘tin-dinner-inner’, with the base holding liquids and the upper part solid food.

two

Prison and Other Punishments

PRISON, TRIAL AND JURY

English law has sanctioned the use of imprisonment for more than 1,000 years. In the ninth and tenth centuries, legislators such as Alfred and Athelstan formalised the use of prison sentences, typically 40 to 120 days, sometimes accompanied by a fine, for a range of crimes including oath-breaking, theft, witchcraft, sorcery and murder. Establishing guilt for such offences might involve the accused undergoing the ‘threefold ordeal’: first, the ordeal of hot iron (carrying a pound weight of the hot metal for a certain distance); second, the ordeal of hot water (the retrieval of a stone hanging by a string in a pitcher of boiling water); third, the ordeal of the accursed morsel (swallowing a piece of bread accompanied by a prayer that it would choke him if he were guilty).7 Survival of these ordeals with little or no harm, or with an injury that healed very quickly, was taken as a sign of innocence.

The Normans, following their invasion of England in 1066, introduced an alternative form of ordeal, namely trial by combat or ‘wager of battle’. This could take place where, for example, an offender accused another person of being the instigator or an accomplice in the crime. The person thus accused, the ‘appellee’, could demand wager of battle against his accuser, the ‘appellant’. If defeated, the appellee was liable to be hung; if he won, the appellee was pardoned. The right to wager of battle was last claimed as recently as 1818 by Abraham Thornton. After Thornton was acquitted of murdering a girl named Mary Ashford, her brother mounted a private prosecution, in response to which Thornton was granted his request for battle. However, the brother withdrew before any combat took place.

The roots of the modern English justice system were created a century after the Conquest when, in 1166, Henry II issued an Act known as the Assize of Clarendon. The Assize is often credited with laying down the origins of the jury system by setting up a grand or ‘presenting’ jury in each district which was to notify the king’s roving judges of the most serious crimes committed there. Clause 7 of the Assize also provided a significant impetus to the use of prisons – it decreed that the sheriff of each county was required to erect a county gaol if none already existed, with the cost being met by the crown.

CATEGORIES OF OFFENCE

As the English system evolved, a classification of different types of offence became established. Although their precise definitions changed over the centuries, the main broad categories of crime were high treason, petty treason, felony and misdemeanour.

High treason was an offence against the monarch or the safety of the realm, originally defined by a statute of Edward III in 1350–51.8 Treasonable offences included: ‘compassing or imagining the king’s death’; violating the king’s wife or eldest daughter (but only if she was unmarried); waging war against the king or aiding his enemies; slaying the king’s chancellor, treasurer or judges; and counterfeiting the currency of the realm.

Petty treason was a treason against a royal subject, in particular the murder of someone to whom allegiance was owed, such as a master killed by his servant, or a husband by his wife.

Felony, a word which originally meant ‘forfeiture’, was a broad category of more serious offence which at one time was punishable by the forfeiture of land or goods, but for which death later became the usual penalty. The main types of felony were murder, rape, larceny (i.e. theft), robbery (i.e. theft with violence) and burglary. However, many specific offences were later added to the list: for example, stealing a hawk became a felony in the reign of Edward III.

Misdemeanours, in contrast to felonies, were less serious offences not involving forfeiture of property.

The traditional punishment for misdemeanours was whipping, the stocks or pillory, or a fine, while that for treason was death.9 Felonies could be capital or non-capital depending on the particular offence – which ones received the death penalty changed over the centuries.

THE GROWTH OF PRISONS

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the use of prisons became more widespread. By 1216, all but five counties had complied with the Assize of Clarendon and set up gaols which were often situated in the castles that existed in most county towns.10 Increasingly, other large towns set up their own gaols, with castles again being a popular location.

In the capital, the Tower of London and Fleet prison were used to hold the king’s debtors as well as ‘contumacious excommunicates, those who interfered with the working of the law, failed appellants, attainted jurors, perjurers, frauds, and those who misinformed the courts’.11

In the main, though, imprisonment was still not regarded as a punishment in itself, but rather a means for keeping offenders in secure custody while awaiting trial or execution, or until they had paid a fine that had been imposed or a debt that was owed. Nonetheless, there was a steady growth of offences for which the penalty was a term in prison. The use of imprisonment for debtors to the crown, which began in 1178, was extended to all debtors in 1352. Other offences, such as aiding a prisoner to escape, prostitution and brothel-keeping, also became punishable by prison. Between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, a gaol term – typically ranging from forty days to a year and a day – became the penalty for around 180 additional offences, including seditious slander, corruption and selling shoddy or underweight goods.12

SPECIAL-PURPOSE PRISONS

Not all prisons were operated by the civil authorities. The stannary courts at Lydford in Devon and Lostwithiel in Cornwall judged cases involving tin-miners and had their own prisons.

In the royal forests, which in the medieval period numbered eighty and covered three tenths of England, ‘forest law’ applied. Introduced by William the Conqueror, forest law prohibited not only unauthorised hunting, but almost anything that might be considered harmful to the animals or their habitat, such as felling trees, cutting peat or even – in some cases – collecting firewood. Penalties for offenders included fines and imprisonment, with forest prisons being set up in 1361 at Lyndhurst in Hampshire, and in 1446 at Clarendon Palace in Wiltshire. 13

A number of prisons were also established by the Church and religious communities. The Bishop of Winchester maintained a small prison for disobedient clerics from 860. By 1076, the punishments inflicted on the inmates included scourging with rods, solitary confinement and a bread and water diet. In 1107, construction began of a new palace, chapel and two prisons (one for men and one for women), on land owned by the bishop at Southwark, the area later becoming known as the Liberty of the Clink. In 1161, the bishop gained the right to license brothels and prostitutes in the Liberty. A ‘Winchester goose’ subsequently became a popular name both for one of the women and also for a venereal condition that was characterised by a swelling in the groin.14

In 1332, the Archbishop of York erected a large gaol at Hexham, three storeys high, with two dungeons.15 It was used to hold transgressors from his estates in the ecclesiastical liberty of Hexhamshire. Part of the Lollard’s Tower at Lambeth Palace was used by the Archbishop of Canterbury to detain free-thinking (and therefore heretical) followers of John Wycliffe, translator of the Bible into English. The Bishop of London also maintained a prison within the precincts of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Monasteries and abbeys often included a prison amongst their buildings. At Fountains Abbey, three cells were constructed in the basement of the abbot’s house. Each had its own latrine and the inmates were chained to an iron staple which was set into the floor. Excavations in the nineteenth century revealed some Latin graffiti which indicate that the cells were used for disobedient monks rather than lay brothers. The scribblings on one of the walls included the phrase Vale libertas (‘Farewell freedom’).16

BENEFIT OF CLERGY

The Canon Law of ecclesiastical courts and the Common Law of the king’s courts sometimes came to conflicting conclusions about the appropriate punishment for a crime perpetrated by someone in holy orders. To resolve this situation, Common Law courts relinquished the use of the death penalty for some less serious capital offences if committed by a member of the clergy. Instead, a lesser punishment was administered, typically a whipping or short prison sentence.

In 1305, the Benefit of Clergy, as it came to be known, was extended to secular clerks who could read and write Latin. It was later broadened to include anyone with a tonsure – the monk’s traditional shaven crown – and finally to anyone who was literate. When faced with the possibility of the death penalty, an offender could demonstrate his entitlement to Benefit of Clergy by ‘calling for the book’ – the Bible – from which he would read aloud. The usual text was the so-called ‘neck verse’: ‘Have mercy upon me, O God, according to thy loving kindness: according unto the multitude of thy tender mercies blot out my transgressions.’17

Capital offences for which the death penalty could be evaded in this way were classed as ‘clergyable’ and their number steadily grew, with murder on the highway being included from 1512 and privily [secretly] stealing from the person in 1565. However, increasing abuse of the privilege led, from the sixteenth century, to an increasing number of existing offences being deemed non-clergyable. These included murder, rape, robbery, witchcraft and stealing a horse, later joined by the stealing of sheep or mail.18

A common ploy for claiming Benefit of Clergy by someone who was not literate was simply to memorise the neck verse. In one famous case during the time of Edward III, the accused man appeared to read equally fluently regardless of which way round the Bible was given to him – it transpired that he had been coached by two boys let in to visit him by the gaoler. Another ruse was to shave the defendant’s head in the style of the tonsure, again with the gaoler’s assistance sometimes being provided.19

Oxford’s county gaol, dating from around 1166, was built within the town’s Norman castle and operated on the same site until 1996. St George’s Tower survived the prison being rebuilt in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and dominates this 1940’s view of the prisoners’ exercise yard.

Lydford Castle, built in 1195, was the administrative centre for the Royal Forest of Dartmoor and included a prison amongst its facilities. It was also home to the Stannary Court, which ruled on matters related to tin mining in Devon. The court’s strict laws stipulated that a miner found guilty of adulterating tin for fraudulent purposes would have three spoonfuls of molten tin poured down his throat.

A branding iron from Lancaster Castle. Anyone claiming Benefit of Clergy was marked on the thumb with a letter ‘M’ (for Murderer) or ‘T’ (for Thief) so that if he repeated such a crime, he would not evade execution again.

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

Despite the gradual growth in the use of prison as a punishment, the sentence for most serious crimes remained the death penalty. Execution had an obvious attraction in that it permanently disposed of the offender and so removed any possibility of further transgression. In the case of treason and other political crimes, a dead opponent could not indulge in any further plotting. For more commonplace offences, execution – carried out in a highly public and bloody manner – was viewed as a valuable deterrent for those who might be tempted to break the law.

For the highest in the land, beheading was the usual mode of execution, with two of Henry VIII’s wives, Ann Boleyn and Kathryn Howard, among the best known to suffer this fate. For lesser mortals, however, the most usual form of the death penalty was hanging. In some cases the punishment was that of being hung, drawn and quartered or – more accurately – being drawn, hung, disembowelled, beheaded and quartered. Such executions often began with the victim being drawn through the streets attached to a hurdle. The hanging that followed did not necessarily result in death. Someone left hanging would eventually expire from asphyxiation but to experience the full agony of execution required that they be cut down before death, revived, and then castrated and disembowelled, with the pieces being burned. The body was finally decapitated and cut into four quarters with the pieces sometimes being boiled or coated in pitch if they were to be displayed.

The addition to the hanging procedure of a ‘drop’ through a trapdoor seems to have first appeared during the eighteenth century, possibly at the execution, in 1760, of Laurence Ferrers ‘the Murderous Earl’, for the shooting of his steward. The extra distance dropped caused the victim’s neck to break and resulted in a much quicker death. This development had already been pre-empted by Guy Fawkes, the last of the Gunpowder Plot conspirators to be executed in 1606 at Old Palace Yard in Westminster. Having climbed up the ladder to the scaffold and with the hangman’s rope around his neck, Fawkes leapt off and broke his neck, saving himself from experiencing the pain of disembowelment and quartering.

VARIETIES OF EXECUTION

As well as beheading and hanging, a number of other forms of execution were used at different times in the past. Burning to death was often used to deal with those found guilty of religious heresy or witchcraft. It first appeared on the statute book in the 1401 De Haeretico Comburendo or Statute of Heresy. The first victim, in 1402, was William Sautre for, amongst other heresies, his denial of transubstantiation. During the reign of Mary I, nearly 300 Protestants were burned, including thirteen in a single day at Stratford-le-Bow.20

For many years, it was the practice for women convicted of treason or petty treason to be burned at the stake, while men who were guilty of these offences would be hung, drawn and quartered. It became the custom for those facing the stake to be strangled with a rope immediately beforehand so that their death would not be unnecessarily prolonged. Occasionally, this procedure went awry – as in the case of Catherine Hayes, who in 1726 was executed at Tyburn for the murder of her husband. The executioner was in the process of strangling her but the already lit fire scorched his hands, causing him to leave hold before she had become unconscious, resulting in an agonising death.

In 1531, Henry VIII instituted the punishment of boiling alive for those found guilty of murder by poisoning. The penalty was introduced after Richard Roose, cook at the Bishop of Rochester’s palace at Lambeth, had poisoned a pot of soup – as a joke, he claimed – with the result that two people died. Roose was boiled to death at Smithfield the following year. This form of execution was abolished by Edward VI in 1547.

A rather different form of execution was applied to prisoners who refused to make a plea, without which a trial could not proceed. The legal remedy for this refusal was peine forte et dure or pressing to death, whereby the victim was stripped and placed on the ground under a board with rocks piled on top until he either died or agreed to plead. For someone clearly determined not to plead, death could be hastened by placing a sharp stone under their back.21 The area in London’s Newgate prison where this procedure was carried out became known as the Press Yard. Pressing was abolished in 1772 and prisoners refusing to plead were then treated as guilty.

MORE OFFENCES AND MORE ESCAPE CLAUSES

The number of crimes punishable by death increased dramatically during the eighteenth century, rising from around fifty offences in 1688, to 160 in 1765, and 225 by 1815 – a body of legislation which has come to be known as the ‘Bloody Code’. In 1722, a single measure, the ‘Waltham Black Act’ which aimed to curtail a rise in poaching, added around fifty capital offences to the statute book, none of which could be evaded by claiming Benefit of Clergy.

An execution outside Newgate in 1806. Prior to their abolition in 1868, public executions attracted huge crowds, with the well-to-do paying large sums to hire rooms overlooking the gallows. In Dickens’ Oliver Twist, Fagin was executed at Newgate where ‘a great multitude had already assembled; the windows were filled with people, smoking and playing cards to beguile the time. Everything told of life and animation, but one dark cluster of objects and in the very centre of all – the black stage, the cross-beam, the rope, and all the hideous apparatus of death.’

Although beheading by use of a machine is usually associated with eighteenth-century French physician Joseph Guillotin, falling-blade devices were in use in both England and Scotland several centuries before. The Halifax Gibbet, shown here, was in operation by at least 1541, and claimed almost fifty victims over the next hundred years.

An illustration of highway robber William Spiggott undergoing the press at Newgate in 1721. Spiggott withstood a weight of 350lb for half an hour but finally agreed to plead after a further 50lb was added. In due course he was convicted and hanged.

Despite the increase in the number of capital offences, and the clampdown on the use of Benefit of Clergy, the number who were actually executed was rather smaller than might be imagined. Judges could dismiss cases or hand down milder sentences. Juries, too, could return a ‘partial verdict’ and convict defendants for lesser offences than those for which they had originally been indicted. A typical example in the case of grand larceny – stealing goods worth a shilling or more, and an offence which attracted the death penalty – was to return a verdict of petty larceny – stealing goods worth less than a shilling, and which involved a lesser penalty. To rationalise such decisions, the goods in question could be undervalued or the verdict linked to only one item of a larger theft. This sometimes led to absurd decisions, such as the case in 1751 where a home counties jury found the accused guilty of stealing eleven half-crown coins (£1 7s 6d) which were agreed to have a total value of 10d.22

Even where the death sentence had been passed, pardons and reprieves were common. Although a reprieve was technically just the postponement of a sentence for an interval of time, it often led to a full pardon. One potential reprieve for females facing the death penalty was known as the ‘benefit of the belly’. A woman declaring herself to be pregnant would not be hanged until after the birth of her innocent child. However, the sentence was rarely then carried out and effectively resulted in a pardon. Although such claims of pregnancy were supposed to be verified by a midwife, it seems doubtful whether this was taken seriously. Between 1559 and 1625, 38 per cent of convicted female felons in one court circuit successfully claimed that they were expecting. 23 At Newgate, women awaiting execution were placed together in a large ward on the top floor from where the widespread and open soliciting for men to provide this means of reprieve was known to shock visitors to the prison. 24

OTHER PUNISHMENTS

For offences not serious enough to warrant the death penalty, a wide variety of unpleasant physical punishments evolved. These included the pillory, the stocks, whipping and mutilation.

The pillory was a post against which an offender was made to stand for a few hours and suffer public display, ridicule, abuse or – if unlucky – physical assault. In its earliest form, the occupant was kept in place by having his ear nailed to the post. At the end of the allotted time, the ear was simply cut off. This allowed a crude form of record keeping – a second offence would lead to loss of the other ear and a third one to hanging. 25 Later versions of the device included a wooden frame with holes for clamping the head and hands of those placed there. The pillory was used for a wide variety of transgressions, especially ‘public nuisance’ offences, such as selling tainted or underweight food. Evidence of the offence was often attached to the pilloried person – a fishmonger selling stale fish might be adorned with a collar of his wares.26 Use of the pillory largely ceased in 1815, although its use for perjury continued until 1837.

The stocks, as revealed by the Acts of the Apostles, were known to the Romans – Paul and Silas’ gaoler ‘thrust them into the inner prison, and made their feet fast in the stocks’. 27 Like the pillory, the stocks had holes for locking an offender’s legs, wrists or head in place, but were often positioned near the ground to allow the occupant to sit. Although stocks were used to expose offenders such as vagrants or drunkards to public indignity, they could also serve as an alternative to prison to confine someone until being brought before a Justice. In Scotland, a comparable device known as the ‘joug’ consisted of a hinged iron collar attached to a wall or post. The name may be the origin of ‘jug’ – one of the slang terms for prison.28

Two men suffer the indignities of the pillory – the nearer one appears to have been hit on the forehead by one of the throng.

The 1530 Whipping Act decreed that vagrants were to be ‘tied to the end of a cart, naked, and beaten with whips throughout such market town till the body shall be bloody’. A small concession was made in 1597 with the victim only being stripped to the waist. Whipping-posts, often combined with pillories, were also used for carrying out the punishment, although the cart tail continued to be used for vagrants and cases where the whipping was ordered to be carried out from one place to another. Whipping in public was abolished in 1817.

Perhaps the most gruesome form of physical punishment was that of bodily mutilation. In 1176, during the reign of Henry II, crimes such as robbery, false coining and arson could result in the amputation of the right hand and right foot.29 Under the Brawling Act of 1551 (not repealed until 1828) the penalty for anyone convicted of fighting in a church or churchyard was to have one of his ears cut off – or, if having no ears, to be branded on the cheek with the letter ‘F’ for ‘fray-maker’. Under Elizabeth I, punishments for seditious libel included the removal of the right hand. A writer named Stubbs had a cleaver driven through his wrist with a mallet. The event was witnessed by historian William Camden who recalled that:

Stubbs, when his right hand was cut off, plucked off his hat with the left, and said, with a loud voice, ‘God Save the Queen!’ The multitude standing about was deeply silent, either out of horror of this new and unwonted kind of punishment, or out of commiseration towards the man.30

three

Early English Prisons

London, as well as being the country’s largest city and the seat of government, also boasted England’s largest concentration of prisons. In 1623, John Taylor’s verse-pamphlet The Praise and Vertue of a Jayle and Jaylers listed eighteen establishments then in operation. A century later, Daniel Defoe counted twenty-seven public gaols, together with a large assortment of ‘tolerated prisons.’31

Some London prisons, such as the Fleet, Marshalsea, Clink and King’s Bench, were under the direct control of the crown and used, first and foremost, for those who had committed some kind of offence against the monarch. Other prisons were run by the City of London – these included Newgate, Ludgate and the Counters (or ‘Compters’) at Poultry and Wood Street. Newgate was the general holding prison for criminals awaiting trial for offences committed in London and Middlesex. Ludgate was used for the detention of the city’s freemen and freewomen who had committed misdemeanours, although it came to be used almost entirely as a debtor’s prison.32 The two Counters, operated by London’s two sheriffs, dealt speedily with those offending against the city’s ordinances, including those causing a breach of the peace, and also housed debtors.

THE TOWER OF LONDON

Pre-eminent amongst London’s prisons was the Tower of London. The Tower, whose construction was begun by William the Conqueror, served as a fortress, royal residence, ordnance depot and mint, but was also used as a prison for more than 800 years. As the securest stronghold in the kingdom, its main function was the confinement of what were considered the most dangerous class of offenders – those accused of high treason.

The Tower’s first inmate was Ranulf Flambard, imprisoned in the White Tower by Henry I after the suspicious death of Henry’s predecessor William Rufus. Flambard was also the first person ever to escape from the Tower. In February 1101, a rope was smuggled in to him in a large flagon of wine which he invited his guards to share. After they became drunk and fell asleep, he climbed down the rope to the foot of the Tower, where his friends had horses waiting to make his escape.

In 1305, Scottish resistance leader William Wallace, now famous as Braveheart, was imprisoned in the Tower prior to his execution for treason by Edward I. He was one of the first to undergo the fate of being hung, drawn and quartered. His dismembered limbs were despatched separately for display in Perth, Stirling, Berwick and Newcastle.

Other well-known detainees at the Tower included the ‘little princes’ (Edward V and his brother Richard, the Duke of York), Guy Fawkes, Sir Walter Raleigh and Samuel Pepys. In 1820, after the failure of their plan to assassinate the entire British cabinet, the Cato Street Conspirators were held in the Tower. Their gang, led by Arthur Thistlewood, were the last persons to be beheaded by the axe in Britain. 33

A nineteenth-century plan of the Tower of London showing the Bloody Tower (B), St Peter’s Chapel (C), the Green (G), the Jewel House (J), the Lieutenant’s Lodgings (L), the Queen’s Lodgings (Q), the site of the Scaffold (S) and the White Tower (W).

THE FLEET

The Fleet prison was founded, probably in the late eleventh century, on the eastern bank of the River Fleet, just outside the Ludgate entrance to London. The prison was used by the king to hold those charged with offences against the state, including those of the highest rank.

In around 1335, a ten-foot-wide moat was built around the prison so that it was entirely surrounded with water. However, the prison’s neighbours decided that the moat would make an excellent drain for the waste from their stables, lavatories and sewers. Within twenty years the moat was in a filthy state, a situation made worse in 1354 when a riverside wharf near the prison was let to some butchers as a place to deposit the entrails of slaughtered cattle. The moat soon became so congested with offal that it was possible to walk across it.34

The Fleet was later used to house debtors and bankrupts, and, as at some other prisons, payment of a fee to the gaoler could allow an inmate to reside in a designated area outside the prison – the Liberty of the Fleet.

MARSHALSEA

The Marshalsea (whose keeper was known as the Marshal) was erected in around 1329, at the north side of what is now Mermaid Court, off Borough High Street in Southwark. It originally held offenders who were members of the king’s household but was later used for the confinement of debtors, pirates, mutineers and recusants – those refusing to acknowledge the established Church. Edmund Bonner, London’s last Roman Catholic bishop, was imprisoned in Marshalsea for the final ten years of his life after refusing to swear the oath of supremacy to Queen Elizabeth.

In 1811, the Marshalsea was rebuilt a little way to the south of its original location, on the site of the White Lion prison. The father of twelve-year-old Charles Dickens was sent there in 1824 owing £40 10s. The prison later featured in Dickens’ stories such as Little Dorrit and David Copperfield.

THE KING’S BENCH

The King’s Bench prison was located near the Marshalsea on Southwark’s Borough High Street. It originally held those being tried by the King’s Bench Court, which dealt with offences directly affecting the king himself, and also those privileged enough to be tried only before the king. However, it largely came to be used for debtors and for those convicted of libel.

In 1755–8 the prison was relocated a short distance to Blackman Street, but had to be rebuilt after it was burned down during a riot in 1780. Thomas Allen, in his 1829 History of the County of Surrey, portrays an almost holiday-camp atmosphere within its confines:

The prison occupies an extensive area of ground; it consists of one large pile of building, about 120 yards long. The south, or principal front, has a pediment, under which is a chapel. There are four pumps of spring and river water. Here are 224 rooms, or apartments, eight of which are called state-rooms, which are much larger than the others. Within the walls are a coffee-house and two public-houses; and the shops and stalls for meat, vegetables, and necessaries of almost every description, give the place the appearance of a public market; while the numbers of people walking about, or engaged in various amusements, are little calculated to impress the stranger with an idea of distress, or even of confinement.

In addition to the hospitable conditions within the prison, inmates of the King’s Bench could purchase ‘Liberty of the Rules’, which allowed them to live outside the prison within an area about 3 miles across. Not surprisingly, the King’s Bench was said to be ‘the most desirable place of incarceration for debtors in England’ – so much so that ‘persons so situated frequently removed themselves to it by habeas corpus from the most distant prisons in the kingdom’.35

THE CLINK

By around 1500, the Bishop of Winchester’s prison in Southwark’s Liberty of the Clink had become known simply as ‘the Clink’ – a name that turned into a popular slang word for a prison. Although it was used for the detention of local breakers of the peace, the Clink was particularly employed for holding religious offenders, both priests and lay recusants.

The Oath of Allegiance, introduced under James I in 1606, allowed Roman Catholics to acknowledge their loyalty to the English king as head of the realm in what some viewed as a less objectionable way to that required by Henry VIII’s Oath of Supremacy. In the years that followed, a number of priests who took this path, despite a prohibition by the Pope, were housed in the Clink,36 notably the archpriest George Blackwell, who died there in 1613.